Abstract

Parental employment provides many benefits to children's health. However, an increasing number of studies have observed associations between mothers' full-time employment and less healthful family food environments. Few studies have examined other ways in which parental employment may be associated with the family food environment, including the role of fathers' employment and parents' stress balancing work and home obligations. This study utilized data from Project F-EAT, a population-based study of a socio-demographically diverse sample of 3709 parents of adolescents living in a metropolitan area in the Midwestern United States, to examine cross-sectional associations between mothers' and fathers' employment status and parents' work-life stress with multiple aspects of the family food environment. Among parents participating in Project F-EAT, 64% of fathers and 46% of mothers were full-time employed, while 25% of fathers and 37% of mothers were not employed. Results showed that full-time employed mothers reported fewer family meals, less frequent encouragement of their adolescents' healthful eating, lower fruit and vegetable intake, and less time spent on food preparation, compared to part-time and not-employed mothers, after adjusting for socio-demographics. Full-time employed fathers reported significantly fewer hours of food preparation; no other associations were seen between fathers' employment status and characteristics of the family food environment. In contrast, higher work-life stress among both parents was associated with less healthful family food environment characteristics including less frequent family meals and more frequent sugar-sweetened beverage and fast food consumption by parents. Among dual-parent families, taking into account the employment characteristics of the other parent did not substantially alter the relationships between work-life stress and family food environment characteristics. While parental employment is beneficial for many families, identifying policy and programmatic strategies to reduce parents' work-life stress may have positive implications for the family food environment and for the eating patterns and related health outcomes of children and parents.

Keywords: USA, Employment, Nutrition, Family, Stress, Home food environment, Family meals, Parents

Introduction

Working mothers and dual-career families have become normative in many countries. For example, in the United States in 2008, 71% of women with children under 18 years of age were employed and among married couples, almost 60% reported that both spouses were employed (U.S. Department of Labor, 2010b). Although the literature is not conclusive, parental employment has been found to have a beneficial effect on many of children's health and developmental outcomes including higher self-esteem (Sleskova et al., 2006), fewer social and emotional problems (McMunn, Kelly, Cable, & Bartley, 2011), reduced risk of being uninsured (Rolett, Parker, Heck, & Makuc, 2001), higher vaccination rates (Mindlin, Jenkins, & Law, 2009), and greater academic achievement among daughters (Goldberg, Prause, Lucas-Thompson, & Himsel, 2008).

While maternal employment and dual-parent employment impart many benefits, several studies have observed significant relationships between maternal employment and children's weight, with higher amounts of hours that mothers work or mothers' full-time employment associated with children's increased risk for obesity (Brown, Broom, Nicholson, & Bittman, 2010; Gaina, Sekine, Chandola, Marmot, & Kagamimori, 2009; Hawkins, Cole, & Law, 2008; Morrissey, Dunifon, & Kalil, 2011). One explanation for this relationship between maternal employment and children's risk for obesity is that traditional gender roles implicate meal preparation and feeding of children as primarily the responsibility of women (Schafer, Schafer, Dunbar, & Keith, 1999). Thus, factors in the family environment that promote healthful eating including the healthfulness of foods available in the home (Haerens et al., 2008; Hanson, Neumark-Sztainer, Eisenberg, Story, & Wall, 2005) and consumed at meals (French, Story, Neumark-Sztainer, Fulkerson, & Hannan, 2001; Guthrie, Lin, & Frazao, 2002), the frequency of family meals (Hammons & Fiese, 2011), and parental modeling of and support for children's healthful eating (Patrick & Nicklas, 2005), may suffer when women work outside the home. There is some evidence to support this hypothesis. Working mothers have been found to preserve time with their children at the expense of other activities (Bianchi, 2000), and therefore spend less time meal planning, grocery shopping, cooking, and eating with their children compared to non-employed mothers (Cawley & Liu, 2007; Crepinsek & Burstein, 2004). Employed mothers have been found to more frequently purchase prepared foods including fast food and carry-out food, more frequently consume food away from home (Cawley & Liu, 2007; Crepinsek & Burstein, 2004), and commonly report missing out on family meals (Cawley & Liu, 2007; Devine et al., 2009). Few studies have examined the role of fathers' employment on the family food environment or children's dietary intake (Gaina et al., 2009; Gillespie & Achterberg, 1989), although those that have found few associations, potentially due to the small numbers of unemployed fathers in the study samples.

Given that maternal employment is a reality for many families, it is important to not only understand the potential impact of parental employment on families' nutrition opportunities, but also explore how modifiable work-related characteristics may affect the quality of the family food environment. Literature examining the dietary choices of employed adults demonstrates that individuals with low job status, poor job conditions, high work demands, low control at work, and high levels of work-life stress are less likely to have a healthful diet and frequently skip meals (Devine, Connors, Sobal, & Bisogni, 2003; Devine, Stoddard, Barbeau, Naishadham, & Sorensen, 2007; McCann, Warnick, & Knopp, 1990; Marmot et al., 1991). Parents' healthful eating behavior is not only important for their own health and chronic disease prevention, but also for the development of such behaviors among children (Patrick & Nicklas, 2005). In a qualitative study examining the influence of conflict between work and family obligations on employed parents' own dietary choices and strategies to feed their families, Devine et al. (2006) observed that parents selected less healthful food for themselves and for their families' meals not only because they were fast and easy to obtain or prepare, but because they were viewed as a treat or reward to make up for a difficult work day and outings to fast food or pizza restaurants provided an opportunity for a calm and rewarding family event.

While the relationships between maternal employment and reliance on less healthful meal choices have been documented, several gaps in the literature remain. First, little research has examined the role of fathers' employment status in the family food environment. As the gender roles of men are evolving and men may be taking on more responsibility for childcare and chores at home (Cawley & Liu, 2007; Guauthier & Furstenberg, 2004), as well as with the current economic downturn greater numbers of men are un- or underemployed (U.S. Department of Labor, 2010a), fathers' employment characteristics may have a growing importance for the family food environment. Second, few large-scale studies have been conducted to examine how parents' experience of work-life stress may affect families' healthful eating. The majority of previous research have been qualitative by design or have utilized small study samples (Devine et al., 2003, 2006). Third, little is known of how parental employment and work-life stress are specifically associated with the family food environments of adolescent-aged children, as the large majority of previous studies have focused on the home environments of younger children or children of all ages (Brown et al., 2010; Fertig, Glomm, & Tchernis, 2009; Hawkins, Cole, & Law, 2009). Unlike young children, adolescents can be responsible for meal preparation and family food purchases (Larson, Story, Eisenberg, & Neumark-Sztainer, 2006). Therefore, parental employment may have less of a deleterious association with unhealthful family food environment characteristics. Alternatively, parental employment and associated stress may play a larger role in the family food environments of adolescents since parents may be less inclined to make an effort to have regular family meals and support healthful eating if they assume that their adolescent children can manage without their help.

With these unaddressed areas in mind, the current study aims to examine cross-sectional associations between parents' employment status and experience of work-life stress and qualities of the family food environment including the frequency of family meals and time spent preparing meals, as well as parents' own dietary patterns. Study findings have implications for understanding the factors in families' lives that support or hinder the development of health-promoting family environments, and can inform the development of worksite policies and practices, community resources that support working parents and their families, and family-based nutrition-promotion interventions.

Methods

Study population and design

Data for the current study were drawn from Project F-EAT, a population-based study of parents of adolescents. Project F-EAT surveys were completed by a sample of 3709 parents or guardians of the adolescents enrolled in the EAT 2010 study. Adolescent participants in EAT 2010 (n = 2893) were recruited from 20 public middle and high schools in the Minneapolis/St. Paul metropolitan area of Minnesota. Adolescents completed study surveys during the 2009–2010 school year, and as part of this process each participant was asked to identify up to two parents or guardians whom they perceived to be their main caregivers. Approximately 30% of adolescents provided contact information for one parent/guardian and 70% provided information for two parents/guardians.

Questions were developed to capture key constructs related to weight-related behaviors and outcomes with subsequent review by content experts, and were field tested with 28 socioeconomically and ethnically/racially diverse parents. Test–retest reliability was assessed using an additional sample of 102 parents who completed the survey twice over two weeks. Data collection for Project F-EAT was conducted by the Wilder Research Foundation between October 2009 and October 2010. Parent surveys were collected via mail and by phone interviews. Both forms of the survey were available in English, Spanish, Hmong, and Somali, and the telephone interview was additionally offered in Oromo, Amharic, and Karen. A total of 4777 surveys were mailed to parents/guardians of adolescents and 77.6% of parents responded; 85% of the adolescents had at least one parent respond (n = 2382) and 68% (n = 1327) of the adolescents who provided information on two parents had both parents respond. Parental response rates did not differ by adolescent gender, age, socio-economic status, or language spoken at home; but rates did differ by race/ethnicity with the highest response rates among the parents of white adolescents. Parental response rates were 92.4% if the adolescent was white, 82.4% if African American, 85.8% if Hispanic, 85.8% if Asian American, 74.5% if Native American, and 82.8% if mixed/other. For the current analysis, data for parents who reported that the child in EAT 2010 lived with them all of the time or most of the time were included in the analyses. Two samples were used in the current study, (1) the 1183 male parents/guardians and 2073 female parents/guardians (herein referred to as fathers and mothers) who participated in Project F-EAT and EAT 2010, and (2) a sub-sample of 961 families with opposite-gender co-habiting parents where both parents in the home returned a study survey. The University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures.

Measures

Employment status was assessed with the question: ‘Which of the following best describes your current work situation?’ Response options included: ‘working full-time’; ‘working part-time’; ‘stay-at-home caregiver’; ‘currently unemployed but actively seeking work’; and ‘not working for pay’ (Birnbaum et al., 2002). Test–retest for this item was r = 0.82.

Work-life stress was assessed using a scale consisting of the following three items: ‘Because of the requirements of my job, I miss out on home or family activities that I would prefer to participant in’; ‘Because of the requirements of my job, my family time is less enjoyable or more pressured’; and ‘Working leaves me with too little time or energy to be the kind of parent I want to be.’ Four response options ranged from ‘Strongly disagree’ to ‘Strongly agree’ (Cronbach's alpha = 0.86; test–retest r = 0.75) (Marshall & Barnett, 1991, 1993). A three-level variable indicating low, moderate, and high work-life stress was created by excluding parents who reported that they were not employed and dividing the employed parents' responses into tertiles.

Frequency of family meals was assessed with the question: ‘During the past week, how many times did all, or most, of your family living in your household eat a meal together?’ Response options ranged from ‘never’ to ‘more than 7 times.’ (test–retest r = 0.72) (Fulkerson, Neumark-Sztainer, & Story, 2006).

Fast food served at family meals was assessed with the question: ‘During the past week, how many times was a family meal purchased from a fast food restaurant and eaten together either at the restaurant or at home?’ (test–retest r = 0.43) (Boutelle, Fulkerson, Neumark-Sztainer, Story, & French, 2007). The percent of families reporting 1 or more fast food family meals in the past week was calculated.

Food preparation time was measured with the single, openended question, ‘How many hours per week do you normally spend preparing food for your family?’ (Demo & Acock, 1993).

Encouragement of healthful eating was assessed with the question, ‘How often in the past year have you had a conversation with your child about healthy eating habits?’ Response options ranged from ‘never or rarely’ to ‘almost every day’ (test–retest = 0.73) (Lytle, Birnbaum, Boutelle, & Murray, 1999).

Parents' dietary habits were measured by a series of questions. Parents' breakfast frequency was measured with the item, ‘During the past week, how many days did you eat breakfast?’ Response options ranged from ‘never’ to ‘every day’ (test–retest = 0.82) (Boutelle, Birkeland, Hannan, Story, & Neumark-Sztainer, 2007). Parents' fruit and vegetable intake was assessed with two items asking in the past week, how many servings of fruit and vegetables they ate. A serving of fruit was defined as half a cup of fruit or 100% fruit juice or a medium piece of fruit. A serving of vegetables was defined as half a cup of cooked vegetables or one cup of raw vegetables (test–retest = 0.72) (Hanson et al., 2005). Response options ranged from ‘zero servings per day’ to ‘5 or more servings per day’. Parents' intake of sugar-sweetened beverages was measured with the question, ‘Thinking back over the past week, how often did you drink sugar-sweetened beverages (regular soda pop, Kool-Aid)?’ Response options ranged from ‘Less than once per week’ to ‘2 or more per day’ Parents' fast food intake was measured with five survey items asking how often in the past month did you eat something from a traditional “burger-and-fries” fast food restaurant, a Mexican fast food restaurant, a fried chicken restaurant, a sandwich or sub shop, or a pizza place. Response options for these items ranged from ‘never/rarely’ to ‘1 + times per day’ (Nelson & Lytle, 2009). Responses were recoded to reflect intake per week and items were summed to create a weekly measure of parents' total fast food intake (Test–retest r = 0.75).

Socio-demographic characteristics, including relationship status, race/ethnicity, household income, educational attainment, age, number of children in the household, and primary language(s) spoken in the home were based on self-report. Relationship status was assessed with the question, “What is your current marital status?” and response options included, ‘married or in a committed relationship,’ ‘divorced/separated,’ ‘single,’ ‘widowed,’ and ‘other.’ This relationship status variable was dichotomized and categories included ‘married or in a committed relationship’ and ‘divorced/widowed/single.’ Parents who reported their relationship status as ‘other’ (n = 23) were excluded from the analyses. Race/ethnicity was assessed with one survey item: ‘Do you think of yourself as 1) white, 2) black or African—American, 3) Hispanic or Latino, 4) Asian—American, 5) Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, or 6) American Indian or Native American’ and respondents were asked to check all that apply. Participants who checked two options were categorized as ‘mixed/other race.’ Hawaiian/Pacific Islander and Native American participants were also categorized as ‘mixed/other race’ due to their small numbers in this dataset. Household income was assessed with the question: ‘What was the total income of your household before taxes in the past year?’ (test–retest r = 0.94). Educational attainment was assessed with the question: ‘What is the highest grade or year of school that you have completed?’ (test–retest r = 0.84) (Birnbaum et al., 2002). Age was assessed by subtracting date of birth from the date the survey was completed. Primary languages spoken in the home were self-reported by the adolescent as “English”, “a language other than English”, or “English and another language equally” (Yu, Huang, Schwalberg, Overpeck, & Kogan, 2003).

Statistical analysis

First, as in many cases adolescents only had one parent participate in the study, the study sample of all parents was used and analyses examined mothers and fathers separately rather than as a family unit. Gender-specific linear regression models were developed to examine cross-sectional associations between parental employment status and the family food environment variables, adjusted for socio-demographic covariates. Adjusted means were calculated from the linear regression models and when the overall F statistic was significant at p < 0.05, post-hoc comparisons between adjusted means were conducted to identify statistically significant sources of differences. Differences in the family environment and parental behavior across the five levels of parental employment were examined, and after analyses indicated that there were few differences in the family food environments of stay-at-home caregivers, currently unemployed parents, and not-employed parents, these three categories were collapsed into a single ‘not currently employed’ category. Linear regression models were used to examine associations between work-life stress among employed parents and the outcomes. Some households had two adults of the same gender complete a survey (n = 67) and in gender-stratified analyses these parents did not provide unique information. Therefore, generalized estimating equations were used to account for the clustering of data among these same-sex parents. The resulting estimates did not differ from those obtained from the generalized linear models, therefore results from the GLM models are presented.

Second, in order to examine the joint contributions of mothers' and fathers' employment and work-life stress on the study outcomes, a sub-sample of parents in the study population who were co-habitating with each other were selected for analysis. These two parents were both Project F-EAT participants and therefore provided full data on their employment and dietary behaviors. In this sample, same-sex adults who were co-habitating were excluded to more fully understand the dynamics between opposite-sex parents. Socio-demographic characteristics reported by the first parent to respond to the Project F-EAT survey were utilized in order to reduce the potential for highly co-linear covariates. Among this sub-sample, interactions between mothers' and fathers' employment status and mothers' and fathers' work-life stress and the study outcomes were examined to determine if the relationships between each parents' employment and the outcomes varied by the other parents' employment. If no statistical interaction was observed, the relationships between parents' employment and work-life stress and the study outcomes were examined with and without taking into account the other parent.

Results

Parental employment status and work-life stress among full parent sample

Among fathers, 63.6% were full-time employed, 11.2% were part-time employed, 4.5% were stay-at-home caregivers, 11.7% were actively seeking employment, and 9.0% were not working for pay. Among mothers, 45.6% were full-time employed, 17.8% were part-time employed, 14.1% were stay-at-home caregivers, 10.3% were actively seeking employment, and 12.2% were not working for pay. After collapsing the three categories of parents who were not currently working due to similarities in their family food environments, differences in parents' race/ethnicity and education, and household income, language spoken in the home, and number of children in the home were observed between parents who were full-time, part-time, and currently not employed (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of mothers and fathers in full-study sample by employment status.

| Fathers | Mothers | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Full time | Part time | Not employed | P | Full time | Part time | Not employed | P | |

| Total %(n) | 63.6 (752) | 11.2 (133) | 25.2 (298) | 45.6 (945) | 17.8 (368) | 36.7 (760) | ||

| Relationship status | ||||||||

| Married/committed relationship | 91.5 (688) | 85.0 (113) | 78.9 (235) | 64.8 (612) | 59.2 (218) | 59.1 (449) | ||

| Divorced/widowed/single | 8.5 (64) | 15.0 (20) | 21.1 (63) | <0.001 | 35.2 (333) | 40.8 (150) | 40.9 (311) | 0.03 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| White | 38.2 (287) | 18.8 (25) | 15.1 (45) | 37.4 (353) | 32.9 (121) | 17.1 (130) | ||

| African American/black | 16.0 (120) | 24.8 (33) | 27.2 (81) | 24.6 (232) | 30.4 (112) | 31.5 (239) | ||

| Hispanic | 22.9 (172) | 31.6 (33) | 9.7(29) | 17.4 (164) | 22.0 (81) | 14.9 (113) | ||

| Asian | 19.8 (149) | 19.5 (42) | 42.0 (125) | 16.9 (160) | 10.3 (38) | 28.2 (214) | ||

| Mixed/other | 3.2 (149) | 5.3 (7) | 6.0 (18) | <0.001 | 3.8 (36) | 4.4 (121) | 8.4 (64) | <0.001 |

| Household income | ||||||||

| <$20,000 | 13.0 (95) | 43.8 (56) | 50.5 (144) | 16.3 (151) | 43.7 (156) | 62.2 (446) | ||

| $20,000–$34,999 | 21.1 (155) | 19.5 (25) | 24.6 (70) | 26.3 (243) | 21.3 (76) | 19.1 (137) | ||

| $35,000–$49,999 | 20.7 (152) | 15.6 (20) | 10.2 (29) | 20.6 (190) | 12.3 (44) | 10.7 (77) | ||

| $50,000–$74,999 | 18.1 (133) | 14.8 (19) | 7.7 (19) | 18.0 (166) | 10.6 (38) | 4.7 (34) | ||

| >$75,000 | 27.2 (200) | 6.3 (8) | 8.1 (23) | <0.001 | 18.8 (174) | 12.0 (43) | 3.2 (23) | <0.001 |

| Education | ||||||||

| Did not complete high school | 21.4 (161) | 33.8 (45) | 46.0 (137) | 19.6 (185) | 26.9 (99) | 48.3 (367) | ||

| Completed high school | 23.0 (173) | 22.6 (30) | 20.8 (62) | 19.9 (188) | 21.7 (80) | 21.5 (163) | ||

| Some college | 27.7 (208) | 21.1 (28) | 21.5 (64) | 30.0 (283) | 27.5 (101) | 21.1 (160) | ||

| Completed college | 27.9 (210) | 22.6 (30) | 11.7 (35) | <0.001 | 30.6 (289) | 23.9 (88) | 9.2 (70) | <0.001 |

| Primary language spoken in home | ||||||||

| English | 56.5 (424) | 43.6 (58) | 48.0 (142) | 64.6 (610) | 61.1 (225) | 50.3 (381) | ||

| Language other than English | 15.1 (113) | 16.3 (35) | 15.2 (45) | 12.0 (113) | 17.9 (66) | 17.6 (133) | ||

| Equally English and another language | 28.5 (214) | 30.1 (40) | 36.8 (109) | <0.001 | 23.4 (221) | 20.9 (77) | 244 (32.2) | <0.001 |

| Mean (SD) age | 43.9 (7.6) 0.02 | 43.3 (8.2) | 45.4 (10.9) | 0.02 | 41.5 (7.3) | 40.6 (7.9) | 41.5(8.8) | 0.15 |

| Number of children in household | 2.7 (1.6) | 3.3 (2.1) | 3.2 (2.0) | <0.001 | 2.5 (1.6) | 2.6 (1.5) | 3.3 (1.9) | <0.001 |

| Mean (SD) work-family stress (range: 1–12) | 7.3 (2.4) 0.06 | 6.8 (2.1) | 0.06 | 7.3 (2.4) | 6.5 (2.2) | <0.001 | ||

Parental employment status

Numerous differences were observed in the family food environment by mothers' employment status, but not fathers' employment status, after adjustment for socio-demographic characteristics (Table 2). Full-time employed mothers reported having significantly fewer family meals per week, were more likely to have fast food for family meals, spent less time preparing food, provided less encouragement for their child to eat healthfully, and consumed fewer fruits and vegetables per day, compared to other mothers. Not-employed mothers reported drinking sugar-sweetened beverages more frequently than either full-time or part-time employed mothers (p = 0.003). This is the only outcome for which mothers who were not employed reported a less healthful behavior compared to full-time employed mothers (Table 2).

Table 2.

Frequency and characteristics of family meals, encouragement of children's healthful eating, and dietary behavior modeling by parents' employment status among full-study sample.

| Fathers | Mothers | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Full time (n = 752) |

Part time (n = 133) |

Not employed (n = 298) |

Pdf=2 | Full time (n = 945) |

Part time (n = 368) |

Not employed (n = 760) |

Pdf=2 | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | |||

| Family meal frequency (times/week) | 4.7 (0.12) | 5.3 (0.28) | 5.1 (0.20) | 0.10 | 4.5 (0.10)a | 5.0 (0.16)b | 5.1 (0.12)b | <0.001 |

| Percent reporting 1+/week fast food for family meals | 61.9% (0.02) | 61.2% (0.04) | 56.3% (0.03) | 0.33 | 64.5% (0.02) | 65.1% (0.03) | 57.4% (0.02) | 0.01 |

| Food preparation (hours/week) | 4.7 (0.23)a | 6.8 (0.56)b | 7.4 (0.39)b | <0.001 | 8.8 (0.26)a | 10.1 (0.41)b | 11.5 (0.30)c | <0.001 |

| Encourage child's healthful eating (Range: 1–5) | 2.8 (0.05) | 2.9 (0.11) | 2.9 (0.08) | 0.70 | 3.0 (0.04)a | 3.1 (0.07)b | 3.1 (0.05)b | 0.01 |

| Parents' breakfast frequency (times/week) | 4.5 (0.10) | 4.4 (0.24) | 4.3 (0.17) | 0.52 | 4.3 (0.08) | 4.5 (0.13) | 4.5 (0.10) | 0.20 |

| Parents' fruit and vegetable intake (servings/day) | 3.3 (0.08) | 3.6 (0.19) | 3.6 (0.13) | 0.20 | 3.6 (0.07)a | 3.9 (0.11)b | 3.9 (0.08)b | 0.003 |

| Parents' sugar-sweetened beverage intake (times/week) | 2.8 (0.04) | 2.4 (0.09) | 3.1 (0.06) | 0.15 | 2.1 (0.03)a | 2.3 (0.05)a | 2.7 (0.04)b | 0.003 |

| Parents' fast food intake (times/week) | 1.4 (0.03) | 1.3 (0.07) | 1.3 (0.05) | 0.47 | 1.3 (0.02) | 1.2 (0.04) | 1.1 (0.03) | 0.10 |

Notes:

Models adjusted for relationship status, race/ethnicity, education, age, language spoken at home, and number of children in home.

Square-root transformed variables used for sugar-sweetened beverage intake and fast food intake.

Adjusted means with different superscripts are statistically different using a p value of p < 0.05.

Only one difference was observed in the family food environment or fathers' dietary behaviors by fathers' employment status. Full-time employed fathers reported spending significantly fewer hours on food preparation per week than part-time or not-employed fathers, with hours of fathers' food preparation ranging from 4.7 among full-time employed fathers to 7.4 among fathers who were not employed (p < 0.001). Of interest, hours of food preparation were higher among mothers than fathers irrespective of employment status, with mothers' weekly hours of food preparation ranging from 8.8 h among full-time employed mothers to 11.5 h among not-employed mothers.

Work-life stress

Among both mothers and fathers, higher work-life stress was associated with several less healthful family food environment characteristics and parental behaviors after adjustment for socio-demographic characteristics and full- or part-time employment status (Table 3). For both parents, higher levels of work-life stress were associated with less frequent family meals, lower consumption of fruits and vegetables, and more frequent fast food intake. Additionally, higher work-life stress was associated with less frequent breakfast intake (p = 0.01) and lower encouragement of healthful eating (p = 0.01) among fathers.

Table 3.

Frequency and characteristics of family meals, encouragement of children's healthful eating, and dietary behavior modeling by parents' work-life stress among full-study sample.

| Fathers' work-life stress | Mothers' work-life stress | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Low (n = 358) |

Moderate (n = 250) |

High (n = 269) |

Pdf=2 | Low (n = 561) |

Moderate (n = 335) |

High (n = 370) |

Pdf=2 | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | |||

| Family meal Frequency (times/week) | 5.7 (0.17)a | 4.7 (0.19)b | 4.1 (0.19)c | <0.001 | 5.5 (0.18)a | 4.7 (0.12)b | 4.0 (0.16)c | <0.001 |

| Percent reporting 1+/week fast food for family meals | 61.2% (0.03) | 62.7% (0.03) | 64.0% (0.03) | 0.78 | 63.3% (0.03) | 65.2%(0.02) | 65.9% (0.03) | 0.78 |

| Food preparation (hours/week) | 5.5 (0.30)a | 4.7 (0.35)b | 3.9 (0.34)b | 0.002 | 9.2 (0.37) | 8.9 (0.25) | 8.2 (0.33) | 0.11 |

| Encourage child's healthful eating (Range: 1–5) | 2.9 (0.07)a | 2.9 (0.08)a | 2.7 (0.07)b | 0.01 | 3.0 (0.07)a | 3.0 (0.05)ab | 3.2 (0.07)b | 0.03 |

| Parents' breakfast frequency (times/week) | 4.6 (0.15)a | 4.8 (0.17)a | 4.1 (0.17)b | 0.01 | 4.5 (0.15)a | 4.5 (0.10)ab | 4.2 (0.13)b | 0.17 |

| Parents' fruit and vegetable intake (servings/day) | 3.5 (0.11)a | 3.4 (0.13)a | 3.1 (0.12)b | 0.03 | 3.9 (0.12)a | 3.7 (0.08)b | 3.4 (0.11)b | 0.03 |

| Parents' sugar-sweetened beverage intake (times/week) | 2.6 (0.05) | 2.7 (0.06) | 3.1 (0.06) | 0.09 | 2.1 (0.05) | 2.1 (0.04) | 2.4 (0.05) | 0.18 |

| Parents' fast food intake (times/week) | 1.2 (0.04)a | 1.4 (0.04)a | 1.8 (0.04)b | 0.002 | 1.1 (0.04)a | 1.3 (0.02)b | 1.5 (0.03)b | <0.001 |

Notes:

Models adjusted for relationship status, race/ethnicity, education, age, language spoken at home, and number of children in home.

Square-root transformed variables used for sugar-sweetened beverage intake and fast food intake.

Adjusted means with different superscripts are statistically different using a p value of p < 0.05.

Parental employment and work-life stress among the dual-parent household sub-sample

Among the sub-sample of families with two co-habitating parents both enrolled in Project F-EAT, 63.6% of fathers were full-time employed, 11.3% were part-time employed, and 25.1% were currently unemployed. Among mothers in this sub-sample, 49.3% were full-time employed, 17.5% were part-time employed, and 33.2% were currently unemployed. Higher percentages of participants in the sub-sample were white or Asian and more frequently reported a higher household income as compared to the full sample of parents.

Parental employment status

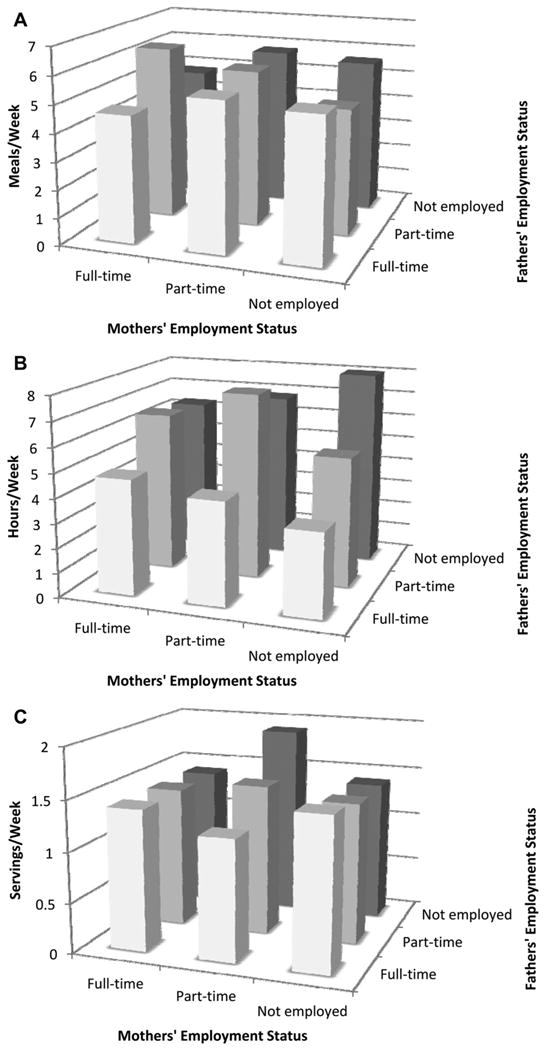

When examining family food environment characteristics among co-habitating mothers and fathers, there was some evidence of interactions between mothers' and fathers' employment status for the outcomes of family meal frequency, fathers' food preparation hours, and mothers' sugar-sweetened beverage consumption (Fig. 1). For example, for the outcome of family meal frequency there was an interaction between mothers' and fathers' employment status (p for interaction <0.05). Among families where the father was either full-time employed or unemployed, the frequency of family meals was higher as mothers worked part-time or were not employed versus full-time employed. However, among families with part-time employed fathers, family meal frequency was highest in families where mothers work full-time. Among outcomes for which there was not an interaction between mothers' and fathers' employment status, only one difference in the family food environment was observed by parents' employment status with full-time employed mothers reporting significantly fewer hours of food preparation than unemployed mothers (Table 4).

Fig. 1.

A: Family meals per week by mothers' and fathers' employment status. B: Fathers' food preparation time by mothers' and fathers' employment status. C: Mothers' sugar-sweetened beverage intake by mothers' and fathers' employment status.

Table 4.

Frequency and characteristics of family meals, encouragement of children's healthful eating, and dietary behavior modeling byparents' employment status among dual-parent sub-sample.

| Fathers | Mothers | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Full time (n = 611) |

Part time (n= 109) |

Not employed (n = 241) |

Model 1 Pdf=2 | Model 2 Pdf=2 | Full time (n = 474) |

Part time (n = 168) |

Not employed (n = 319) |

Model 1 Pdf=2 | Model 2 Pdf=2 | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | |||||

| Family meal frequency (times/week) | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ||||

| Percent reporting 1+/week fast food for family meals | 60.5% (0.02) | 66.7% (0.05) | 59.1% (0.03) | 0.40 | 0.45 | 63.7% (0.02) | 61.9% (0.04) | 55.9% (0.03) | 0.12 | 0.14 |

| Food preparation (total hours/week) | ** | ** | ** | 9.0 (0.37)a | 10.5 (0.61)ab | 11.5 (0.47)b | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Encourage child's healthful eating (Range: 1–5) | 2.8 (0.05) | 2.9 (0.12) | 2.9 (0.08) | 0.76 | 0.71 | 3.0 (0.06) | 3.2 (0.10) | 3.2 (0.07) | 0.10 | 0.09 |

| Parents' breakfast frequency (times/week) | 4.4 (0.11) | 4.4 (0.26) | 4.3 (0.19) | 0.96 | 0.98 | 4.5 (0.12) | 4.8 (0.20) | 4.8 (0.15) | 0.13 | 0.15 |

| Parents' fruit and vegetable intake (servings/day) | 3.3 (0.08) | 3.6 (0.20) | 3.5 (0.14) | 0.14 | 0.14 | 3.6 (0.10) | 3.8 (0.16) | 3.9 (0.12) | 0.19 | 0.20 |

| Parents' sugar-sweetened beverage intake (times/week) | 2.7 (0.04) | 2.1 (0.09) | 2.9 (0.07) | 0.07 | 0.12 | ** | ** | ** | ||

| Parents' fast food intake (times/week) | 1.4 (0.03) | 1.2 (0.07) | 1.3 (0.05) | 0.67 | 0.72 | 1.2 (0.03) | 1.1 (0.05) | 1.0 (0.04) | 0.08 | 0.07 |

Notes:

Significant interaction between fathers' employment and mothers' employment, see Fig. 1.

Model 1 adjusted for primary parents' race/ethnicity, education, and age, language spoken in the home, and number of children in home.

Model 2 additionally adjusted for co-parents' employment status and work-life stress.

Square-root transformed variables used for sugar-sweetened beverage intake and fast food intake.

Adjusted means with different superscripts are statistically different using a p value of p < 0.05.

Work-life stress

When examining relationships between work-life stress and the family food environment among pairs of parents, there was no evidence that the relationships between parents' work-life stress and the family food environment differed by the level of work-life stress their co-parent experienced. However, for both mothers and fathers, higher work-life stress was associated with several less healthful family environment characteristics and parental behaviors, even after accounting for the other parent's work-life stress (Table 5). For example, mothers and fathers with higher work-life stress reported fewer family meals per week, fewer hours of food preparation, and lower fruit and vegetable intake. Fathers experiencing greater work-life stress also reported less encouragement of their child's healthful eating (p = 0.01), less frequent breakfast intake (p = 0.01), and more frequent fast food consumption (p < 0.0001) after taking into account mothers' employment status and work-life stress.

Table 5.

Frequency and characteristics of family meals, encouragement of children's healthful eating, and dietary behavior modeling by parents' work-life stress among dual sub-sample.

| Fathers | Mothers | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Low stress (n = 286) |

Moderate stress (n = 201) |

High stress (n = 227) |

Model 1 Pdf=2 | Model 2 Pdf=2 | Low stress (n = 152) |

Moderate stress (n= 237) |

High stress (n = 243) |

Model 1 Pdf=2 | Model 2 Pdf=2 | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | |||||

| Family meal frequency (times/week) | 5.7 (0.19) | 4.7 (0.22) | 4.7 (0.21) | <0.001 | 0.002 | 5.8 (0.25) | 5.2 (0.20) | 4.3 (0.20) | <0.001 | 0.02 |

| Percent reporting 1+/week fast food for family meals | 59.0% (0.03) | 64.4% (0.03) | 64.8% (0.03) | 0.33 | 0.44 | 59.8% (0.04) | 66.9% (0.03) | 63.3% (0.03) | 0.36 | 0.37 |

| Food preparation (total hours/week) | 5.3 (0.31) | 4.1 (0.37) | 3.7 (0.34) | 0.001 | 0.01 | 9.8 (0.54) | 9.2 (0.42) | 8.0 (0.43) | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| Encourage child's healthful eating (Range: 1–5) | 2.9 (0.07)a | 2.9 (0.09)a | 2.6 (0.08)b | 0.02 | 0.01 | 3.1 (0.10) | 3.0 (0.08) | 3.2 (0.08) | 0.10 | 0.05 |

| Parents' breakfast frequency (times/week) | 4.5 (0.16)a | 4.9 (0.20)a | 3.9 (0.18)b | <0.001 | 0.01 | 4.8 (0.21)ab | 4.9 (0.16)a | 4.3 (0.16)b | 0.02 | 0.07 |

| Parents' fruit and vegetable intake (servings/day) | 3.5 (0.12)a | 3.3 (0.14)ab | 3.0 (0.13)b | 0.03 | 0.04 | 3.8 (0.16)a | 3.9 (0.13)a | 3.4 (0.13)b | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Parents' sugar-sweetened beverage intake (times/week) | 2.4 (0.06) | 2.7 (0.07) | 3.0 (0.07) | 0.11 | 0.06 | 1.6 (0.06) | 1.7 (0.06) | 2.3 (0.07) | 0.007 | 0.29 |

| Parents' fast food intake (times/week) | 1.1 (0.04) | 1.4 (0.05) | 1.7 (0.04) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.9 (0.05) | 1.1 (0.04) | 1.4 (0.04) | 0.003 | 0.16 |

Notes:

Model 1 adjusted for primary parents' race/ethnicity, education, and age, language spoken in the home, and number of children in home.

Model 2 additionally adjusted for co-parents' employment status and work-life stress.

Square-root transformed variables used for sugar-sweetened beverage intake and fast food intake.

Adjusted means with different superscripts are statistically different using a p value of p < 0.05.

Discussion

The family food environment has great potential to contribute to the development and maintenance of children's healthful eating habits and the prevention of excess weight gain (Savage, Fisher, & Birch, 2007). Among the full sample of parents, full-time employed mothers reported several less healthful characteristics of the family food environment and less healthful personal dietary behaviors compared to part-time and not employed mothers; few differences were observed by fathers' employment status. In the sub-sample, fewer associations were observed between mothers' employment status and the family food environment, both before and after adjustment for fathers' employment. This may be because mothers in two-parent families where both parents were able and motivated to participate in Project F-EAT have qualities that enable them to engage in healthful habits despite working full-time. Further research on the characteristics of families for whom both parents participated in the study may shed light on qualities that could help all families have healthier food environments. Meanwhile, high levels of work-life stress were associated with several characteristics of a less healthful family food environment and parents' own dietary habits for mothers and fathers in the full and sub-samples. These associations often persisted when taking into account the employment status and work-life stress of the other parent in the home.

The findings from the full-study sample that the families of employed mothers have less frequent family meals, more frequent fast food for family meals, and spend less time on food preparation align with the findings of several other studies that observed that employed women report having fewer family meals and spend less time in food preparation than non-employed mothers (Cawley & Liu, 2007; Crepinsek & Burstein, 2004; Devine et al., 2009). Additionally, it was observed that full-time working mothers consumed fewer fruits and vegetables themselves, which is important for women's health as well as the potential to affect children's diet quality. It is important to note that some of the differences in the family food environment observed between mothers were relatively small, for example in maternal encouragement of their child to eat healthful food, and therefore may not be extremely meaningful to an individual family. However, the consistency in direction of associations across the multiple family food environment characteristics within this study along with findings of previous studies suggest that efforts such as engaging all family members in meal preparation to alleviate burden on working women could contribute to improvements in family food environments on a population level.

While many relationships were observed between mothers' employment status and the family food environment in the full-study sample, fathers' employment was only associated with less time spent in food preparation. While food preparation time may indicate the extent to which families rely on less healthful convenience foods (Crawford, Ball, Mishra, Salmon, & Timperio, 2007; Larson, Perry, Story, & Neumark-Sztainer, 2006), overall the time often gained by fathers' part-time employment or unemployment does not appear to be making a difference to many qualities of family food environment or fathers' own dietary habits. These findings complement those of Gaina et al. (2009) who did not observe any associations between fathers' employment status and young adolescents' nutrition patterns. Fathers' employment may be unrelated to many family food environment characteristics because traditional gender roles dictate that women are responsible for food in the home, regardless of whether women are employed and despite men having time to devote to prioritizing their families' healthful eating due to less than full-time employment.

The many significant associations observed between both mothers' and fathers' experience of high levels of work-life stress and less healthful family food environment characteristics expands upon previous studies that found poorer dietary intake patterns among workers experiencing high work-life stress (Allen & Armstrong, 2006; Roos, Sarlio-Lahteenkorva, Lallukka, & Lahelma, 2007). The work of Devine and colleagues (Devine et al., 2006; Devine et al., 2007; Devine et al., 2009) along with the current study describe how parents may sacrifice the quality of their home food environment because of work demands and high job stress. Due to current unemployment rates and uneasy economic conditions, parents today may be experiencing great pressure to maintain their employment and thus required to devote more time to their jobs, which could contribute to increased stress as they try to balance the needs of their jobs with the needs of their families.

In light of the many significant associations between parents' experience of work-life stress and less healthful family food environment characteristics, and given the fact that employed parents are the reality of many families, further research to understand the specific barriers to healthful eating that parents with high levels of work-life stress experience would inform efforts to help these families create more healthful family food environments. For example, a more in-depth study of how work-life stress may decrease ease of access to and preparation of healthful food would help identify ways that communities can better support working parents. There are also many promising intervention strategies that have been found to reduce parents' experience of work-life stress including providing benefits for less than full-time employment (Charlesworth, Keen, & Whittenbury, 2009) and allowing employees to have greater control over when and where their work is done (Kelly, Moen, & Tranby, 2011), which may have an added benefit of improving families' healthful eating opportunities. Additionally, behavioral interventions aimed at enhancing parenting skills have been successful in decreasing parents' work-life stress (Martin & Sanders, 2003). Integrating skill-building sessions around food purchasing and preparation, and stress reduction, may provide further benefits of parent-focused interventions to the family food environment.

The inclusion of fathers in the current study allowed for the extension of the findings of previous studies that only addressed the role of mothers' employment in the family food environment. Another strength of the study was that the study population was racially and ethnically diverse, of low to moderate socio-economic status, and resided in an urban setting. This sample of parents reflects the circumstances of many families in the US in the current poor economic climate. However, as few families in the study were of an objectively high socio-economic status it is not known whether families in which there are two high-income wage earners may address time pressures differently. Similarly, as a large percentage of the study population were Asian and specificially of Hmong ethnicity, generalizability of study findings may be limited. An additional limitation of the study was the relatively low test–retest values for a small number of measures, such as that of the frequency with which families have fast food for family meals. This level of reliability may have limited our ability to detect true associations between parental employment and reliance on fast food for family meals. Furthermore, detailed information of parents' employment including number of hours or types of shifts worked, as well as the employment characteristics of other adults in the home, was not available and could inform an understanding of the role of employment in the family food environment.

While the results of this manuscript should not be interpreted as diminishing the importance of parental employment, employment and work demands appear to contribute to parents' decreased time to attend to their own nutrition as well as that of their families. Further research is needed to address remaining gaps in the literature including conducting a more detailed examination of the role of employment characteristics including occupation type, work shifts, and consistency of employment, and further examination of the specific barriers that parents with high work-family stress experience in creating a healthful family food environment. Despite this need for additional research, there are a number of promising intervention strategies, such as modifying workplace policies and helping parents strengthen their parenting skills in order to decrease parents' conflict between work and family obligations, which have great potential help parents provide healthful family food environments.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by Award Number R01HL093247 (D. Neumark-Sztainer, principal investigator) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The first author was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship at the University of Minnesota by Grant Number T32DK083250 (R. Jeffrey) from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Allen TD, Armstrong J. Further examination of the link between work-family conflict and physical health – the role of health-related behaviors. American Behavioral Scientist. 2006;49:1204–1221. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi SM. Maternal employment and time with children: dramatic change or surprising continuity? Demography. 2000;37:401–414. doi: 10.1353/dem.2000.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum AS, Lytle LA, Murray DM, Story M, Perry CL, Boutelle KN. Survey development for assessing correlates of young adolescents' eating. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2002;26:284–295. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.26.4.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutelle KN, Birkeland RW, Hannan PJ, Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D. Associations between maternal concern for healthful eating and maternal eating behaviors, home food availability, and adolescent eating behaviors. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2007;39:248–256. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2007.04.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutelle KN, Fulkerson JA, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, French SA. Fast food for family meals: relationships with parent and adolescent food intake, home food availability and weight status. Public Health Nutrition. 2007;10:16–23. doi: 10.1017/S136898000721794X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JE, Broom DH, Nicholson JM, Bittman M. Do working mothers raise couch potato kids? Maternal employment and children's lifestyle behaviours and weight in early childhood. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;70:1816–1824. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cawley J, Liu F. Maternal employment and childhood obesity: A search for mechanisms in time use data. National Poverty Center Working Paper Series. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth S, Keen M, Whittenbury K. Integrating part-time work in policing services: policy, practice, and potential. Police Practice and Research. 2009;10:31–47. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford D, Ball K, Mishra G, Salmon J, Timperio A. Which food-related behaviours are associated with healthier intakes of fruits and vegetables among women? Public Health Nutrition. 2007;10:256–265. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007246798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crepinsek MK, Burstein NR. Maternal employment and Children's nutritionIn Other Nutrition-Related Outcomes, Vol II. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Demo DH, Acock AC. Family diversity and the division of domestic labor: how much have things really changed? Family Relations. 1993:323–331. [Google Scholar]

- Devine CM, Connors MM, Sobal J, Bisogni CA. Sandwiching it in: spillover of work onto food choices and family roles in low- and moderate-income urban households. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;56:617–630. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00058-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devine CM, Farrell TJ, Blake CE, Jastran M, Wethington E, Bisogni CA. Work conditions and the food choice coping strategies of employed parents. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2009;41:365–370. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devine CM, Jastran M, Jabs J, Wethington E, Farell TJ, Bisogni CA. "A lot of sacrifices:" work-family spillover and the food choice coping strategies of low-wage employed parents. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;63:2591–2603. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devine CM, Stoddard AM, Barbeau EM, Naishadham D, Sorensen G. Work-to-family spillover and fruit and vegetable consumption among construction laborers. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2007;21:175–182. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-21.3.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fertig A, Glomm G, Tchernis R. The connection between maternal employment and childhood obesity: inspecting the mechanisms. Review of Economics of the Household. 2009;7:227–255. [Google Scholar]

- French SA, Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D, Fulkerson JA, Hannan P. Fast food restaurant use among adolescents: associations with nutrient intake, food choices and behavioral and psychosocial variables. International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders. 2001;25:1823–1833. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulkerson JA, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M. Adolescent and parent views of family meals. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2006;106:526–532. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaina A, Sekine M, Chandola T, Marmot M, Kagamimori S. Mother employment status and nutritional patterns in Japanese junior high schoolchildren. International Journal of Obesity. 2009;2005;33:753–757. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2009.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie AH, Achterberg CL. Comparison of family interaction patterns related to food and nutrition. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 1989;89:509–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg WA, Prause J, Lucas-Thompson R, Himsel A. Maternal employment and children's achievement in context: a meta-analysis of four decades of research. Psychological Bulletin. 2008;134:77–108. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guauthier AH, Furstenberg FF. Working more, playing less: Changing patterns of time use among young adults. Network on transitions to adulthood: Policy brief. Philadelphia, PA: MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Transitions to Adulthood and Public Policy; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie JF, Lin BH, Frazao E. Role of food prepared away from home in the American diet, 1977–78 versus 1994–96: changes and consequences. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2002;34:140–150. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60083-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haerens L, Craeynest M, Deforche B, Maes L, Cardon G, De Bourdeaudhuij I. The contribution of psychosocial and home environmental factors in explaining eating behaviours in adolescents. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2008;62:51–59. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammons AJ, Fiese BH. Is frequency of shared family meals related to the nutritional health of children and adolescents? Pediatrics. 2011;127:e1565–1574. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson NI, Neumark-Sztainer D, Eisenberg ME, Story M, Wall M. Associations between parental report of the home food environment and adolescent intakes of fruits, vegetables, and dairy foods. Public Health Nutrition. 2005;8:77–85. doi: 10.1079/phn2005661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins SS, Cole TJ, Law C. Maternal employment and early childhood overweight: findings from the UK Millennium Cohort Study. International Journal of Obesity. 2008;32:30–38. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803682. 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins SS, Cole TJ, Law C. Examining the relationship between maternal employment and health behaviours in 5-year-old British children. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2009;63:999–1004. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.084590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly EL, Moen P, Tranby E. Changing workplaces to reduce work-family conflict: schedule control in a white-Collar Organization. American Sociological Review. 2011;76:265–290. doi: 10.1177/0003122411400056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson NI, Perry CL, Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D. Food preparation by young adults is associated with better diet quality. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2006;106:2001–2007. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson NI, Story M, Eisenberg ME, Neumark-Sztainer D. Food preparation and purchasing roles among adolescents: associations with sociodemographic characteristics and diet quality. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2006;106:211–218. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2005.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lytle LA, Birnbaum A, Boutelle K, Murray DM. Wellness and risk communication from parent to teen: the ìParental Energy Indexî. Health Education. 1999;99:207–214. [Google Scholar]

- McCann BS, Warnick GR, Knopp RH. Changes in plasma lipids and dietary intake accompanying shifts in perceived workload and stress. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1990;52:97–108. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199001000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMunn A, Kelly Y, Cable N, Bartley M. Maternal employment and child socio-emotional behaviour in the UK: longitudinal evidence from the UK Millennium Cohort Study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2011 doi: 10.1136/jech.2010.109553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot MG, Smith GD, Stansfeld S, Patel C, North F, Head J, et al. Health inequalities among British civil servants: the Whitehall II study. Lancet. 1991;337:1387–1393. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)93068-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall NL, Barnett RC. Race, class and multiple role strains and gains among women employed in the service sector. Women and Health. 1991 doi: 10.1300/j013v17n04_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall NL, Barnett RC. Work-family strains and gains among twoearner couples. Journal of Community Psychology. 1993;21(1):64–78. [Google Scholar]

- Martin AJ, Sanders MR. Balancing work and family: a controlled evaluation of the triple P-positive parenting program as a work-site intervention. Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2003;8:161–169. doi: 10.1111/1475-3588.00066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mindlin M, Jenkins R, Law C. Maternal employment and indicators of child health: a systematic review in pre-school children in OECD countries. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2009;63:340–350. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.077073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrissey TW, Dunifon RE, Kalil A. Maternal employment, work Schedules, and Children's Body Mass Index. Child Development. 2011;82:66–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01541.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson MC, Lytle LA. Development and evaluation of a brief screener to estimate fast-food and beverage consumption among adolescents. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2009;109:730–734. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick H, Nicklas TA. A review of family and social determinants of children's eating patterns and diet quality. Journal of the American College of Nutrition. 2005;24:83–92. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2005.10719448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolett A, Parker JD, Heck KE, Makuc DM. Parental employment, family structure, and child's health insurance. Ambulatory Pediatrics. 2001;1:306–313. doi: 10.1367/1539-4409(2001)001<0306:pefsac>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos E, Sarlio-Lahteenkorva S, Lallukka T, Lahelma E. Associations of work-family conflicts with food habits and physical activity. Public Health Nutrition. 2007;10:222–229. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007248487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage JS, Fisher JO, Birch LL. Parental influence on eating behavior: conception to adolescence. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics: A Journal of the American Society of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2007;35:22–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2007.00111.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer RB, Schafer E, Dunbar M, Keith PM. Marital food interaction and dietary behavior. Social Science & Medicine. 1999;48:787–796. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00377-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleskova M, Tuinstra J, Madarasova Geckova A, van Dijk JP, Salonna F, Groothoff JW, et al. Influence of parental employment status on Dutch and Slovak adolescents' health. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:250. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics . Employment status of the civilian noninstitutional population 16 years and over by sex, 1973 to date. Washington, D.C.: 2010a. [Accessed 01.05.11]. Available at www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat2.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics . Women in the labor force: A databook. Washington, D.C.: 2010b. [Accessed 01.05.11]. Available at www.bls.gov/cps/wlf-databook-2010.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Yu SM, Huang ZJ, Schwalberg RH, Overpeck M, Kogan MD. Acculturation and the health and well-being of US immigrant adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2003;33:479–488. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00210-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]