Abstract

Bacterial infection plays a critical role in exacerbations of various lung diseases, including chronic pulmonary obstructive disease (COPD) and asthma. Excessive lung inflammation is a prominent feature in disease exacerbations, but the underlying mechanisms remain poorly understood. Cell surface glycoprotein MUC18 (alias CD146 or melanoma cell adhesion molecule) has been shown to promote metastasis in several tumors, including melanoma. We explored the function of MUC18 in lung inflammatory responses to bacteria (eg, Mycoplasma pneumoniae) involved in lung disease exacerbations. MUC18 expression was increased in alveolar macrophages from lungs of COPD and asthma patients, compared with normal healthy human subjects. Mouse alveolar macrophages also express MUC18. After M. pneumoniae lung infection, Muc18−/− mice exhibited lower levels of the lung proinflammatory cytokines KC and TNF-α and less neutrophil recruitment than Muc18+/+ mice. Alveolar macrophages from Muc18−/− mice produced less KC than those from Muc18+/+ mice. In Muc18−/− mouse alveolar macrophages, adenovirus-mediated MUC18 gene transfer increased KC production. MUC18 amplified proinflammatory responses in alveolar macrophages, in part through enhancing the activation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB). Our results demonstrate, for the first time, that MUC18 exerts a proinflammatory function during lung bacterial infection. Up-regulated MUC18 expression in lungs (eg, in alveolar macrophages) of COPD and asthma patients may contribute to excessive inflammation during disease exacerbations.

Acute exacerbations of respiratory diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma are associated with high morbidity and mortality, and cost billions of dollars for health care.1–6 Excessive pulmonary inflammation is a core feature during acute exacerbations of COPD and asthma. Although bacterial infection [eg, by Mycoplasma pneumoniae (Mp)] is recognized as one of the major triggers in disease exacerbations and progression, the mechanisms leading to an exaggerated lung inflammatory response to bacteria remain poorly understood. A better understanding of excessive lung inflammation during disease exacerbations can likely provide promising approaches to more effective treatments.7 In the present study we sought to reveal a potential mechanism that exaggerates lung inflammatory responses to bacterial infections, such as Mp infection, that are relevant to COPD and asthma acute exacerbations.8–11

MUC18, alias CD146 or melanoma cell adhesion molecule (MCAM), is a 113-kDa transmembrane glycoprotein that has been studied mostly in malignant melanoma.12–16 In the lung, MUC18 expression is observed on endothelial and smooth muscle cells in the airway wall.17 We recently showed that MUC18 is significantly increased in asthmatic airway epithelial cells and is directly up-regulated by Th2 cytokine IL-13 in primary bronchial epithelial cells.18 MUC18 up-regulation was also reported in primary bronchial epithelial cells from patients with COPD.19 Like airway epithelial cells, lung leukocytes (eg, macrophages) also serve as the first line of host defense against invading pathogens. However, the expression and function of MUC18 in lung macrophages have not been investigated previously.

We hypothesized that alveolar macrophages in diseased lungs increase MUC18 expression, which in turn amplifies inflammatory responses to bacterial infection. To test our hypothesis, we analyzed MUC18 expression in alveolar macrophages from COPD and asthma patients. We then used the Muc18 knockout mouse model to define the in vivo function of MUC18 in lung inflammatory responses to bacteria. Moreover, we used primary alveolar macrophage (pAM) cultures to dissect the role of MUC18 in macrophages in regulating proinflammatory cytokine production. Finally, we demonstrated that transcriptional factor nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) is involved in MUC18-mediated production of proinflammatory cytokines.

Materials and Methods

Purification of Human Alveolar Macrophages

To determine MUC18 expression in human pAMs, bronchoalveolar lavage was performed in normal healthy donor lungs obtained through the International Institute for the Advancement of Medicine (Edison, NJ) and National Disease Research Interchange (Philadelphia, PA), as well as in patients with mild to moderate asthma or COPD through bronchoscopy performed at National Jewish Health. Alveolar macrophages were purified by adhering BAL cells to cell culture plates for 2 hours at 37°C in a 5% CO2–enriched atmosphere; cells were then lysed in TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen; Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) for RNA extraction. Real-time PCR was performed for MUC18 mRNA expression.

The criteria and subject characteristics of the asthma and COPD patients have been reported previously.20 The human subject research protocols were approved by our institutional review board, and all subjects provided written informed consent.

MUC18 Immunostaining

To examine MUC18 protein expression in alveolar macrophages, immunostaining was performed in paraffin-embedded lung tissues of normal healthy human donors, patients with moderate to severe COPD, and one patient who died of asthma. Normal lungs were obtained through the International Institute for the Advancement of Medicine and the National Disease Research Interchange. COPD lungs were from the NIH-National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Lung Tissue Research Consortium. The fatally asthmatic lung was obtained at National Jewish Health, as described previously.18 Lung tissue sections were stained with a rabbit anti-human MUC18 antibody or rabbit IgG control antibody (Epitomics, Burlingame, CA), as previously reported.18

To confirm MUC18 expression by macrophages, immunofluorescent double staining with MUC18 and F4/80 in pAMs from Muc18+/+ and Muc18−/− mice was performed as described previously.21–23

Animals

Our use of mice was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of National Jewish Health. Muc18+/− mice on 129SvEvBr background were obtained from Taconic Farms (Hudson, NY; distributed through Lexicon Pharmaceuticals, The Woodlands, TX). Muc18+/+ and Muc18−/− mice were generated by breeding Muc18+/− mice in our biological resource center under pathogen-free housing conditions.

Mp Infection in Mice

Strain FH (15531; ATCC, Manassas, VA) of Mp was prepared as described previously.24–26 Muc18+/+ and Muc18−/− mice (8 to 12 weeks of age) were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (70 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg), and were intranasally inoculated with 50 μL of saline solution or Mp at 1 × 108 colony-forming units (CFU) per mouse. Mice were sacrificed at 4 and 24 hours after Mp infection or saline treatment.

Mouse BAL and Lung Tissue Processing

Mice were euthanized by intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital. The lungs were first lavaged with 1 mL saline solution. An aliquot of BAL (10 μL) was used for Mp culture, as described previously.24,25,27,28 Cell-free BAL fluid was stored at −80°C for cytokine analysis. BAL cell cytospin slides were stained with a Diff-Quick stain kit (IMEB, San Marcos, CA) for cell differential counts or fixed in ice-cold acetone/methanol for MUC18 immunostaining. The lungs were further lavaged four times by using 1× Hank’s balanced salt solution supplemented with 0.5 mol/L EGTA for pAM enrichment. Left lungs were homogenized to quantify Mp levels by culture, as described previously.24,25,27,28

Mouse pAM Culture

BAL cells were collected, spun down, suspended in RPMI 1640 medium with 10% fetal bovine serum, and seeded in 48-well culture plates (4 × 104 cells per well) for 2 hours to allow cells to adhere to cell culture plates. Thereafter, nonadherent cells were removed. Adherent cells were then incubated with or without Mp or the TLR2 agonist Pam2CSK4 (10 ng/mL; InvivoGen, San Diego, CA) for 4 or 24 hours.

Adenovirus-Mediated MUC18 Gene Transfer in Muc18−/− Mouse pAMs

The pAMs from Muc18−/− mice were enriched by adhering BAL cells to 48-well culture plates (1 × 105 cells per well) for 2 hours; pAMs were then infected with replication-deficient type 5 adenovirus–expressing mouse MUC18 cDNA (AdMUC18) (Open Biosystems; Thermo Scientific, Huntsville, AL) or an empty vector (AdControl) at multiplicity of infection (MOI) = 50 for 2 hours. Cells were then washed twice to remove free adenovirus. At 48 hours after infection, cells were used for i) Western blotting, to confirm MUC18 expression after gene transfer; ii) treatment with or without Pam2CSK4 (10 ng/mL) for 24 hours, to examine cytokine KC production; or iii) pretreatment with the selective NF-κB inhibitor helenalin (0.1 μmol/L; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 1 hour, followed by stimulation with Pam2CSK4 (10 ng/mL) for 4 hours, to measure KC production.

ELISA

KC and TNF-α levels in mouse BAL fluid or macrophage culture supernatants were determined by using the respective mouse KC or TNF-α enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) DuoSet development kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). NF-κB p65 activity in mouse alveolar macrophage nuclear proteins was measured by an ELISA-based TransAM NF-κB p65 activation assay (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA).

Quantitative Real-Time RT-PCR

TaqMan gene expression assays for human MUC18 (Hs00174838_m1) and for mouse MUC18 (Mm00522397_m1) were obtained from Applied Biosystems (Life Technologies, Foster City, CA). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed on a CFX96 real-time detection system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). The housekeeping gene GAPDH was evaluated as an internal positive control to normalize MUC18 expression. The comparative threshold cycle method (ΔΔCT) was used to demonstrate relative MUC18 mRNA levels.27,29

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as means ± SEM. One-way analysis of variance was used for multiple comparisons, and a Tukey’s post hoc test was applied where appropriate. Student’s t-test was used when only two groups were compared. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

MUC18 Expression in Human Alveolar Macrophages

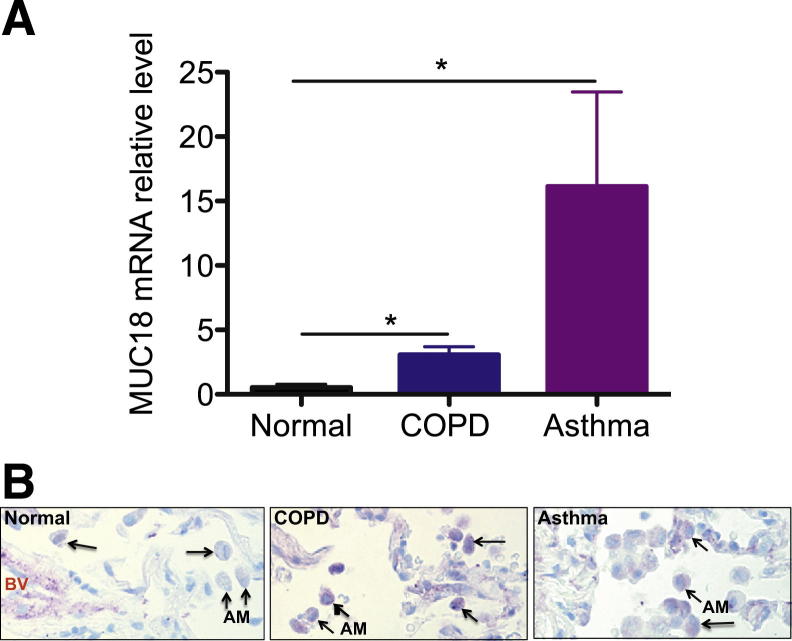

Alveolar macrophages isolated from BAL cells of normal healthy subjects and of patients with COPD or asthma were examined for MUC18 expression. Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. For both COPD and asthma patients, MUC18 mRNA levels in alveolar macrophages were increased, compared with those in healthy subjects (Figure 1A).

Table 1.

Clinicodemographic Characteristics of Study Subjects

| Condition | Sample size | Age (years) | Sex (M/F) | Smoking [pack-yr (no.)] | FEV1 (% predicted) | FVC (% predicted) | FEV1/FVC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | n = 4 | 52.3 ± 4.3 | 2/2 | 0 (4) | NA | NA | NA |

| COPD | n = 4 | 63.3 ± 3.2 | 2/2 | 45.8 ± 11.0 (4) | 67.0 ± 12.3 | 87.5 ± 4.4 | 58.3 ± 10.1 |

| Asthma | n = 4 | 52.3 ± 7.2 | 3/1 | 0 (3), 10 (1) | 86.5 ± 16.6 | 90.5 ± 11.8 | 73.0 ± 6.1 |

Data are expressed as means ± SEM.

F, female; M, male; FVC, forced vital capacity; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in the first second; NA, not available.

Figure 1.

MUC18 expression by human alveolar macrophages. A: MUC18 mRNA expression in isolated alveolar macrophages from healthy subjects (n = 4) and from patients with COPD (n = 4) or asthma (n = 4). Compared with healthy subjects, the COPD and asthma patients exhibited higher levels of MUC18 mRNA expression in alveolar macrophages. B: Representative MUC18 protein immunostaining in human lung tissues. In contrast to alveolar macrophages (arrows) in healthy lung, the alveolar macrophages in COPD and asthma patients had increased MUC18 protein (purple) expression. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. Original magnification, ×400. AM, alveolar macrophage; BV, blood vessel.

We used immunostaining to examine MUC18 protein expression in alveolar macrophages of lung tissue sections from four healthy donors, five COPD patients, and one patient who died of asthma. Alveolar macrophages in healthy lung tissue expressed minimal MUC18 (Figure 1B); however, MUC18 protein was markedly increased in alveolar macrophages of COPD and asthmatic lungs.

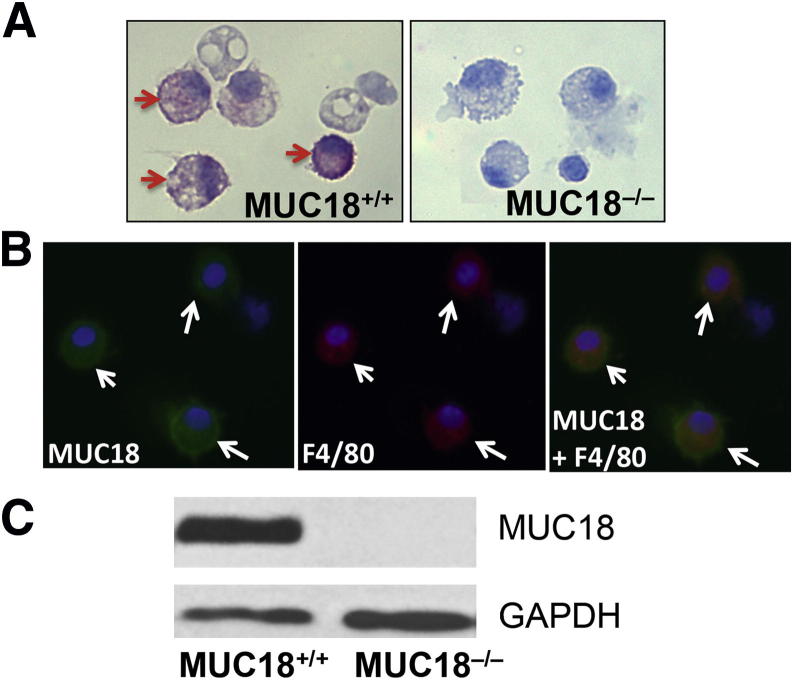

Mouse Primary Alveolar Macrophages Express MUC18

We performed MUC18 protein immunostaining on BAL cell cytospin slides from Muc18+/+ and Muc18−/− mice. No MUC18 staining was seen in any BAL cells of Muc18−/− mice (Figure 2A). In contrast, alveolar macrophages from Muc18+/+ mice exhibited positive MUC18 staining. MUC18 protein localization to macrophages was further confirmed by double immunofluorescent staining of MUC18 and F4/80 (a specific marker of mouse macrophages) (Figure 2B). MUC18 protein expression in isolated alveolar macrophages of Muc18+/+ mice was confirmed by Western blotting (Figure 2C). We also verified MUC18 mRNA expression in isolated alveolar macrophages from Muc18+/+ but not Muc18−/− mice (data not shown).

Figure 2.

MUC18 expression by mouse alveolar macrophages. A: Alveolar macrophages of WT mice (Muc18+/+), but not Muc18 knockout mice (Muc18−/−), stain positive for MUC18 (arrows). B: Double immunofluorescent staining of MUC18 (green) and F4/80 (red) demonstrates MUC18 localization to alveolar macrophages from Muc18+/+ mice (arrows). C: Western blot shows MUC18 protein in alveolar macrophages of Muc18+/+, but not Muc18−/− mice. Original magnification, ×400.

Modulation of Mp Infection-Induced Lung Inflammation by MUC18

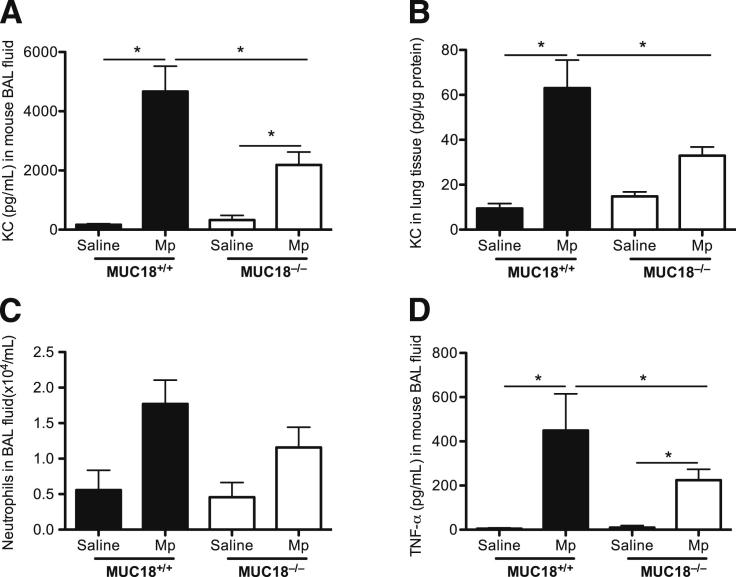

To examine the in vivo function of MUC18, Muc18+/+ and Muc18−/− mice were inoculated with Mp or saline solution for 4 and 24 hours, to quantify leukocytes and lung the proinflammatory cytokines KC and TNF-α.

At 4 hours, compared with the saline control, Mp infection increased KC levels in BAL fluid and lung tissues of both Muc18+/+ and Muc18−/− mice (Figure 3, A and B); however, the postinfection KC levels of Muc18−/− mice were significantly lower (P < 0.05) than in Muc18+/+ mice. KC levels at 24 hours after Mp infection were significantly lower (up to 20-fold), compared with those at 4 hours, in both groups of mice. Thus, the KC differences observed at 4 hours between Muc18+/+ and Muc18−/− mice had disappeared after 24 hours of Mp infection. We then compared BAL neutrophils in Mp-infected Muc18+/+ and Muc18−/− mice. BAL neutrophils at 4 hours tended to be lower in Mp-infected Muc18−/− mice than in Muc18+/+ mice (Figure 3C), but the trend did not reach significance (P = 0.06).

Figure 3.

Proinflammatory cytokines and neutrophils in mouse lungs. Muc18+/+ and Muc18−/− mice were intranasally inoculated with saline solution (control) or with Mp at 1 × 108 CFU per mouse. After 4 hours of infection, KC levels in BAL fluid (A) and lung tissue (B) were significantly lower in Muc18−/− mice than in Muc18+/+ mice. Moreover, levels of neutrophils (C) and TNF-α (D) in BAL fluid of Muc18−/− mice were lower than in Muc18+/+ mice. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 5 to 8 mice per group. *P < 0.05.

We also measured TNF-α levels in BAL fluid, because TNF-α is one of the major cytokines from macrophages that are commonly up-regulated during bacterial infection. TNF-α was increased at 4 hours in Mp-infected Muc18+/+ and Muc18−/− mice, compared with saline-treated mice (Figure 3D). At 24 hours, however, TNF-α levels in BAL fluid were undetectable in both strains of mice.

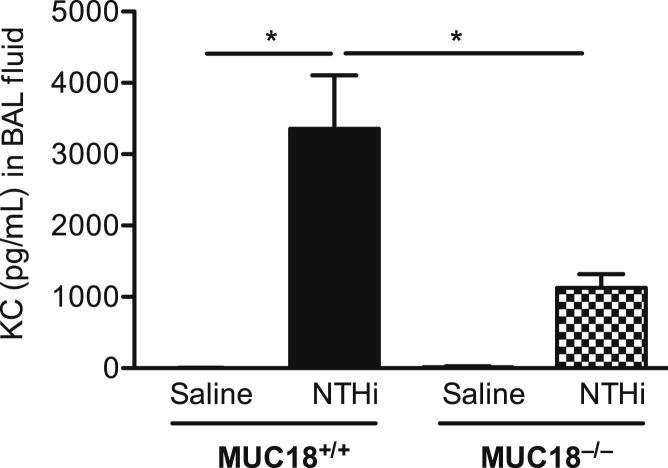

Lung Mp Load in Muc18+/+ and Muc18−/− Mice

In contrast to the lung proinflammatory cytokine findings, the bacterial load (ie, Mp load) was similar in lung tissue and in BAL of Muc18+/+ and Muc18−/− mice at both 4 and 24 hours after Mp infection (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Mp load in lung tissue and BAL. Muc18+/+ and Muc18−/− mice were intranasally inoculated with Mp at 1 × 108 CFU per mouse. After 4 hours (A) and 24 hours (B) of infection, Mp levels were quantified in entire left lungs and in BAL. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 5 to 8 mice per group.

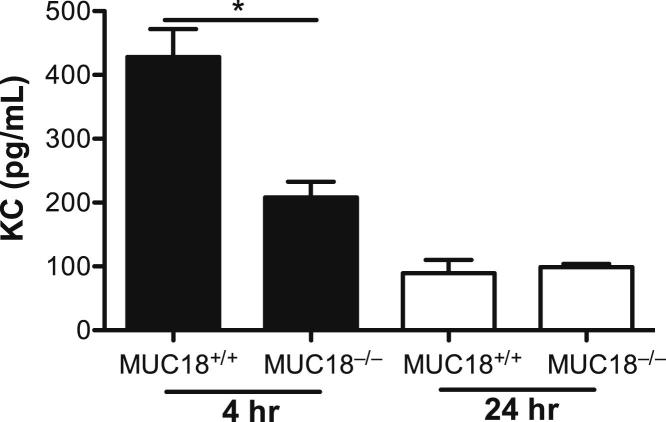

Reduced Cytokine Production in Muc18−/− Mouse Alveolar Macrophages

To determine whether MUC18 deficiency in alveolar macrophages contributes to the reduction of proinflammatory cytokines (KC, in particular) in Muc18−/− mouse lungs after Mp infection, we isolated alveolar macrophages from Mp-infected Muc18+/+ and Muc18−/− mice and cultured them for 24 hours in the absence of Mp. KC levels in supernatants of alveolar macrophages from Mp-infected Muc18−/− mice sacrificed at 4 hours were twofold lower than those from Muc18+/+ mice (P < 0.05) (Figure 5). However, cells from Mp-infected mice of both strains sacrificed at 24 hours did not show significant differences in KC production. Thus, the ex vivo alveolar macrophage KC data were supportive of the BAL fluid data. TNF-α levels in supernatants of alveolar macrophages collected from Mp-infected Muc18+/+ and Muc18−/− mice sacrificed at 4 and 24 hours were undetectable. These results are in accord with our previous report that, unlike intracellular pathogens, the extracellular pathogen Mp increases lung inflammation mainly by increasing other proinflammatory cytokines (eg, KC) rather than TNF-α.28

Figure 5.

Reduced KC production in ex vivo Muc18−/− alveolar macrophages. Alveolar macrophages were isolated from Muc18+/+ and Muc18−/− mice that were intranasally infected with Mp at 1 × 108 CFU per mouse for 4 or 24 hours. Cells were incubated for 24 hours without further stimulation. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 3 replicates. *P < 0.05.

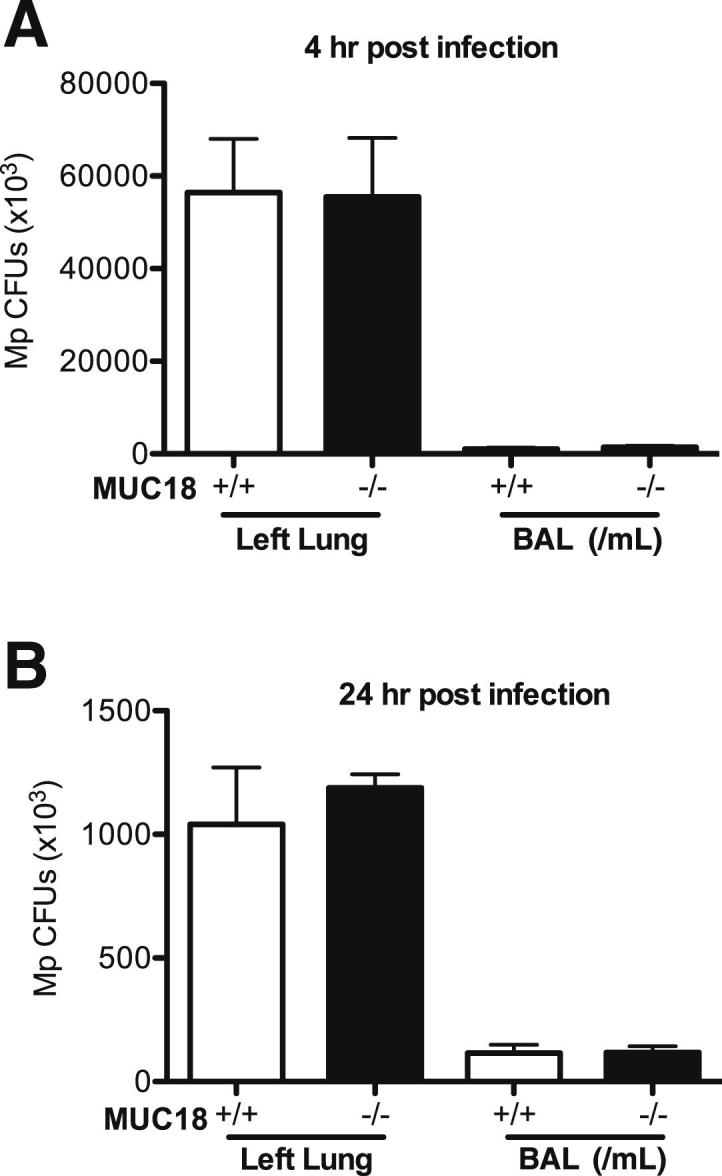

We then isolated alveolar macrophages from Mp-naïve Muc18+/+ and Muc18−/− mice, to further confirm that MUC18 in macrophage promotes KC production after Mp infection. Because Mp initiates inflammatory responses mainly via TLR2 signaling,25 we also stimulated the cells with the TLR2 agonist Pam2CSK4, to test whether MUC18 interacts with TLR2 signaling. In accord with our ex vivo KC data in alveolar macrophages from Mp-infected mice, Muc18−/− cells in vitro produced less KC after Mp infection or Pam2CSK4 stimulation, compared with Muc18+/+ cells (Figure 6, A and B).

Figure 6.

Reduced KC production in in vitro Muc18−/− alveolar macrophages. Alveolar macrophages from Mp-naïve Muc18+/+ and Muc18−/− mice were isolated and treated with medium (−), Mp (MOI = 1), or Pam2CSK4 (Pam2; 10 ng/mL) for 24 hours. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 4 replicates. *P < 0.05.

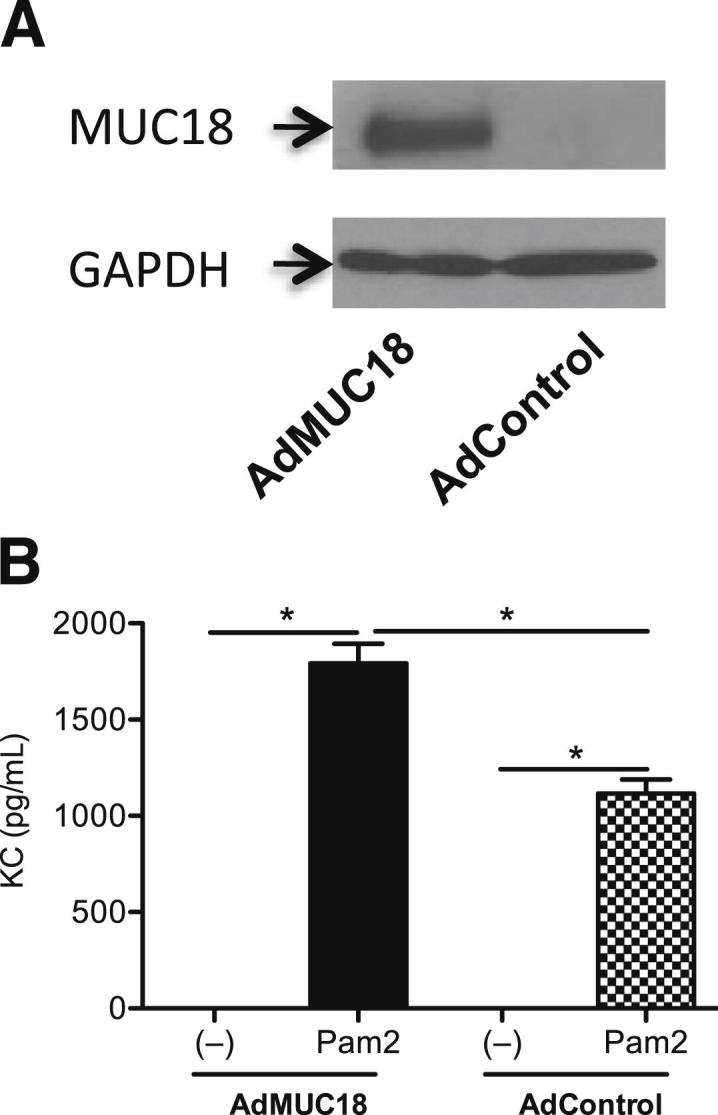

MUC18 Reconstitution in Muc18−/− Mouse Alveolar Macrophages Enhances TLR2 Agonist-Induced Proinflammatory Cytokine Production

Having shown that Muc18 deficiency reduces KC production in vivo and in vitro, we then examined whether restoring MUC18 expression in Muc18−/− mouse alveolar macrophages can reinstate proinflammatory responses to a TLR2 agonist. Primary Muc18−/− alveolar macrophages treated with an adenoviral vector encoding MUC18 cDNA or an empty vector were treated with or without Pam2CSK4. In the absence of Pam2CSK4 stimulation, AdMUC18 (but not AdControl) in Muc18−/− mouse pAMs successfully induced MUC18 protein (Figure 7A). Notably, MUC18 reconstitution in Muc18−/− alveolar macrophages significantly enhanced KC production after TLR2 stimulation (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

Adenovirus-mediated MUC18 gene transfer in Muc18−/− mouse alveolar macrophages resulted in MUC18 protein expression (A) and in amplified KC production after stimulation for 24 hours with the TLR2 agonist Pam2CSK4 (10 ng/mL) (B). Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 3 replicates. *P < 0.05. AdControl, control adenovirus; AdMUC18, adenovirus-expressing mouse MUC18.

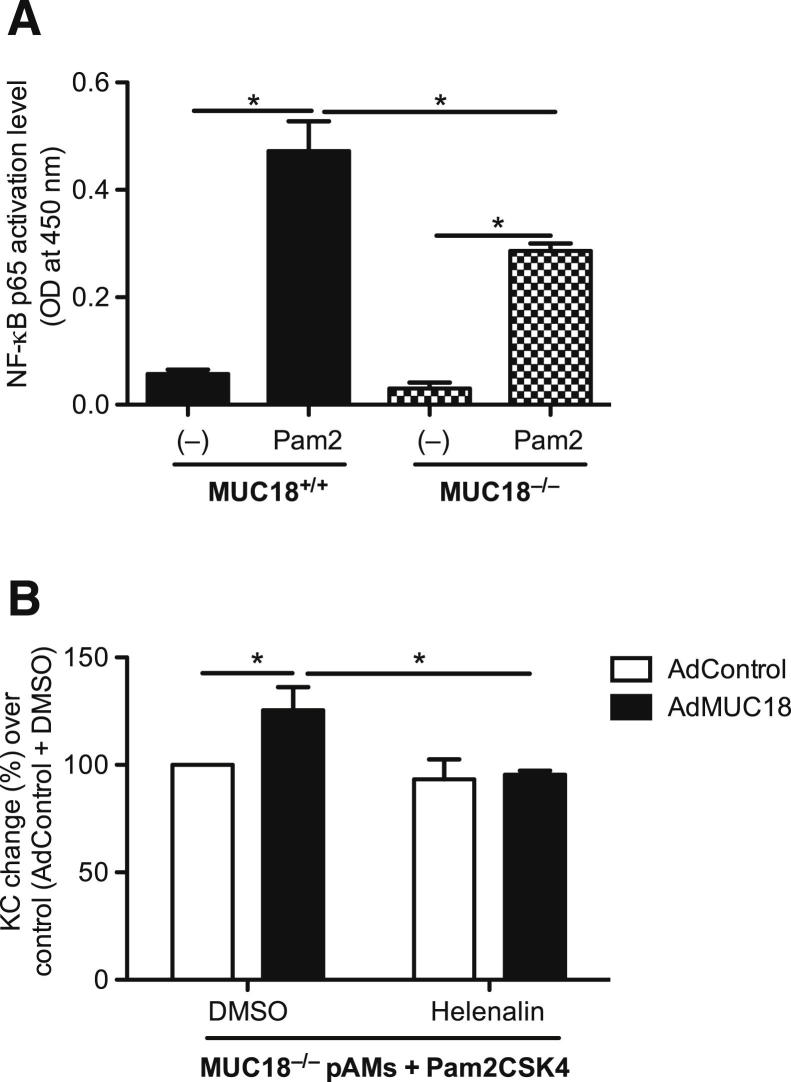

NF-κB Activation Contributes to MUC18-Mediated Proinflammatory Cytokine Production in Mouse Alveolar Macrophages

Our data strongly suggest a proinflammatory role of MUC18 in alveolar macrophages, but the underlying mechanisms remain largely unknown. Production of various proinflammatory cytokines (including KC) depends on NF-κB activation after various stimulants in macrophages.30–32 First, we examined NF-κB p65 activity in isolated alveolar macrophages from Muc18+/+ and Muc18−/− mice. After TLR2 stimulation, Muc18−/− pAMs showed lower NF-κB activation levels than Muc18+/+ pAMs (Figure 8A). Second, to prove the contribution of NF-κB activation to MUC18-mediated proinflammatory cytokine production, Muc18−/− pAMs with adenovirus-mediated MUC18 reconstitution were stimulated with Pam2CSK4 in the absence or presence of the selective NF-κB inhibitor helenalin. Indeed, MUC18-mediated increase of KC at 4 hours after TLR2 stimulation was significantly inhibited by helenalin (Figure 8B). Taken together, our data suggest that MUC18-mediated proinflammatory effects are due in part to activation of NF-κB pathway.

Figure 8.

Role of NF-κB in MUC18-mediated KC production in mouse alveolar macrophages. A: Muc18−/− alveolar macrophages exhibit less nuclear NF-κB p65 activation than Muc18+/+ alveolar macrophages after 30 minutes of stimulation with the TLR2 agonist Pam2CSK4 (10 ng/mL). B: KC induction (4 hours) in Pam2CSK4-stimulated Muc18−/− alveolar macrophages with adenovirus-mediated MUC18 gene transfer is inhibited by the selective NF-κB inhibitor helenalin. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 3 replicates. *P < 0.05. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; OD, optical density.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to reveal the function of MUC18 in the lung. We discovered that alveolar macrophages in COPD and asthma lungs increase MUC18 expression. By using the Muc18 knockout mouse model, we clearly demonstrated a critical role of MUC18 in promoting early lung inflammatory responses to bacteria. Our data suggest that up-regulated MUC18 expression in alveolar macrophages in diseased lungs may contribute to the excessive inflammatory responses to bacteria during acute exacerbations of the disease.

Acute exacerbations of COPD and asthma pose the highest risks to patients (including death), and also the greatest costs for disease-related health care.33 It is imperative to uncover the mechanisms and find more effective therapies to attenuate disease exacerbations and progression. We first demonstrated MUC18 up-regulation in alveolar macrophages of COPD and asthma patients. This finding is in accord with previous reports of increased MUC18 levels in airway epithelial cells from COPD and asthma patients.18,19

The present study is novel for exploration of MUC18 function in the lung in health and disease. Previous studies in MUC18 have focused on its role in tumor growth and metastasis, because MUC18 overexpression has been observed in several types of tumors, including melanoma and prostate cancer.12–14,34 Normally, MUC18 is expressed in vascular endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells, where it is proposed to promote cell–cell adhesions. In the present study, alveolar macrophages in healthy humans expressed negligible MUC18; however, MUC18 expression in alveolar macrophages of COPD and asthma patients was significantly up-regulated.

In the present study, we focused on the function of MUC18 in lung inflammation, but did not address how MUC18 in alveolar macrophages of asthma or COPD patients is up-regulated. In our previous studies in human airway epithelial cells, the Th2 cytokine IL-13 increased MUC18 expression.18 In a preliminary study, we stimulated alveolar macrophages from a nonsmoking healthy human subject with IL-13 (10 ng/mL), and observed a 3.5-fold increase of MUC18 mRNA. A similar result was also seen in IL-13-stimulated alveolar macrophages (1.7-fold increase of MUC18 mRNA) of wild-type (WT) mice. Additionally, our preliminary studies suggested that exposure to cigarette smoke (as opposed to ordinary air) increased MUC18 mRNA expression 4.1-fold in cultured healthy human alveolar macrophages. Future studies are needed to confirm our preliminary data, and to define the underlying molecular mechanisms of MUC18 up-regulation in alveolar macrophages of COPD and asthma patients.

The major strength of the present study is to reveal the proinflammatory function of MUC18 during lung bacterial infection. First, we used the Muc18 knockout mouse model to demonstrate that lack of MUC18 reduces production of the proinflammatory cytokines KC and TNF-α and reduces neutrophil recruitment into the lung soon after Mp infection (at 4 hours). After 24 hours of bacterial infection, however, MUC18 no longer appears to play a major role in lung inflammation (likely because lung inflammation is regulated by multiple factors). Taken together, our in vivo data strongly suggest a proinflammatory function of MUC18 during acute exacerbations of the disease. Although Muc18−/− mice had lower levels of proinflammatory cytokines than the WT mice, lung bacterial Mp load was similar in the two strains of mice. Previous studies also demonstrated inconsistency between inflammation and lung bacterial load.35,36 An appropriate inflammatory response is known to be critical to maintaining host defense against infection. The fact that Muc18−/− mice have lower levels of proinflammatory cytokines than do WT mice, but have similar lung bacterial loads, suggests that blocking up-regulated MUC18 in asthma and COPD patients may reduce excessive inflammation without impairing lung defenses against bacteria.

To define how MUC18 promotes inflammatory responses, we focused on alveolar macrophages, because of their role in exaggerated inflammatory responses to invading pathogens during COPD and asthma exacerbations. To clearly illustrate the role of MUC18, we isolated alveolar macrophages from Muc18 knockout and WT mice. Cytokine induction decreased in MUC18-deficient alveolar macrophages after Mp infection or stimulation with a TLR2 agonist, compared with MUC18-sufficient alveolar macrophages. Conversely, when MUC18-deficient macrophages were transduced with MUC18 cDNA, cytokine production increased. Taken together, our data suggest that MUC18 in alveolar macrophages serves as one of the major mechanisms to enhance lung inflammatory responses to bacteria (eg, Mp).

How MUC18 signals in cells such as macrophages remains a mystery. One could speculate that MUC18 serves as a receptor for bacteria or bacterial components. We conducted a preliminary study in which a MUC18 mutant with truncated extracellular domain was transiently transfected into THP-1 cell-derived macrophages. Compared with the WT MUC18 cDNA transfection, the MUC18 mutant did not reduce KC or TNF-α production after stimulation with the TLR2 agonist Pam2CSK4. Thus, the MUC18 extracellular domain does not likely serve as a receptor for bacterial products such as TLR2 agonist. Future studies are needed to define how the MUC18 cytoplasmic tail interacts with inflammatory signaling pathways after bacterial infection or TLR agonist stimulation.

Because NF-κB is known to regulate various proinflammatory cytokines at the transcriptional level, we examined whether MUC18 promotes NF-κB activation. Indeed, NF-κB activation levels were lower in MUC18-deficient macrophages than those in WT cells. Our NF-κB selective-inhibitor experiments further confirmed that MUC18-mediated proinflammatory cytokine production occurs in part by enhancing NF-κB activation. Although the NF-κB pathway is involved in MUC18-mediated proinflammatory cytokine production, other transcription factors may also be involved. Using an SABiosciences text mining application (Qiagen, Frederick, MD) and the UCSC Genome Browser (http://www.genome.ucsc.edu), we identified several putative transcription factor binding sites in the promoter region of mouse KC gene in addition to NF-κB, including Sp1. To examine whether Sp1 is indeed involved in the proinflammatory function of MUC18, we isolated alveolar macrophages from Muc18−/− mice and reconstituted MUC18 expression by using adenovirus-mediated gene transfer. Thereafter, we stimulated the cells with Pam2CSK4 in the absence or presence of 10 to 100 nmol/L of the Sp1 inhibitor mithramycin A (alias plicamycin), to determine whether Sp1 directly contributes to MUC18-mediated KC production. Adenovirus-mediated MUC18 gene transfer in Muc18−/− alveolar macrophages increased KC production after Pam2CSK4 stimulation; however, MUC18-mediated KC production was not altered by the Sp1 inhibitor. Taken together, our data suggest that Sp1 does not likely play a role in MUC18-mediated KC production in alveolar macrophages, but that other transcription factors (eg, NF-κB) may be important.

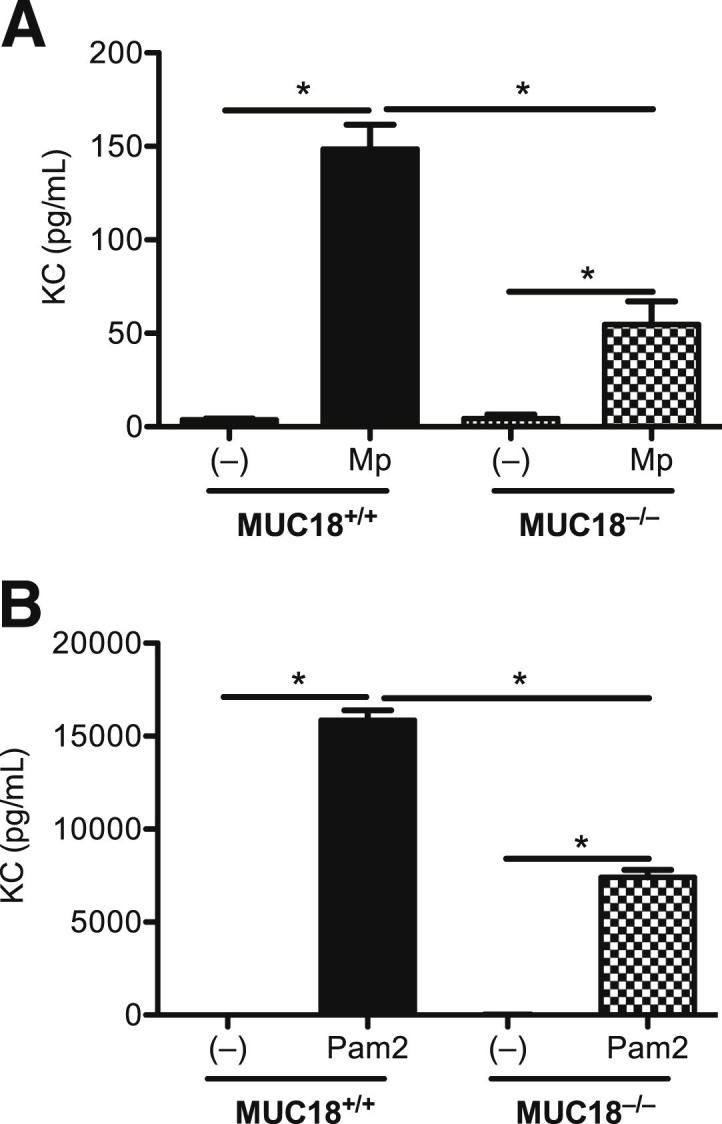

The present study has several limitations. First, prospective studies in alveolar macrophages from normal human subjects and from patients with COPD and asthma would be necessary to define the dependence of bacteria-mediated inflammatory responses on MUC18 expression levels. Second, the relative contribution of MUC18 in alveolar macrophages versus other lung cells (eg, airway epithelial cells) to lung inflammatory responses against bacteria should be defined (eg, by using the mouse bone marrow chimera approach in Muc18+/+ and Muc18−/− mice). Third, the molecular mechanisms by which MUC18 promotes early (but not late) inflammation need to be further defined. Fourth, the present study mainly used MUC18-deficient mice or alveolar macrophages with adenovirus-mediated MUC18 gene transfer to study MUC18 functions. We expect to consider other complementary approaches in future studies, such as anti-MUC18 antibodies in WT mice, to further define MUC18 functions during lung bacterial infection. Finally, the present study used only the mycoplasma infection model to determine MUC18 functions. Further studies are necessary to clarify whether MUC18 is involved in lung inflammatory responses to other strains of respiratory bacteria. In a preliminary study, we infected Muc18+/+ and Muc18−/− mice intranasally with nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae, the most common bacterium seen in COPD lungs (particularly during acute exacerbations). After 4 hours of infection, KC levels in BALF of Muc18−/− were significantly lower than those in Muc18+/+ mice (Figure 9). We conclude, therefore, that MUC18 may regulate lung inflammatory responses to a variety of respiratory pathogens.

Figure 9.

Proinflammatory cytokine KC in mouse BAL fluid. Muc18+/+ and Muc18−/− mice were intranasally inoculated with saline solution (control) or nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae (NTHi) at 1 × 107 CFU per mouse. After 4 hours of infection, BAL fluid was collected for ELISA measurement of KC levels. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 3 or 4 mice per group. *P < 0.05.

In summary, the present pioneering study has revealed a mechanism involving, MUC18 whereby alveolar macrophages in diseased lungs sensitize the host to bacteria-mediated inflammatory responses to invading pathogens. This understanding of the role of MUC18 in exaggerating lung inflammation suggests potential therapeutic options.

Footnotes

Supported in part by NIH grants R01-HL088264 and R01-AI070175 (H.W.C.).

Q.W. and S.R.C. contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Celli B.R., Barnes P.J. Exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2007;29:1224–1238. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00109906. [Erratum appeared in Eur Respir J 2007, 30:401] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anzueto A., Sethi S., Martinez F.J. Exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2007;4:554–564. doi: 10.1513/pats.200701-003FM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rabe K.F., Hurd S., Anzueto A., Barnes P.J., Buist S.A., Calverley P., Fukuchi Y., Jenkins C., Rodriguez-Roisin R., van Weel C., Zielinski J. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease: Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:532–555. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200703-456SO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Halpin D. NICE guidance for COPD. Thorax. 2004;59:181–182. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.021113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dalcin Pde T., Perin C. [Management of acute asthma in adults in the emergency room: current evidence]. Portuguese. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2009;55:82–88. doi: 10.1590/s0104-42302009000100021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Papiris S., Kotanidou A., Malagari K., Roussos C. Clinical review: severe asthma. Crit Care. 2002;6:30–44. doi: 10.1186/cc1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bathoorn E., Kerstjens H., Postma D., Timens W., MacNee W. Airways inflammation and treatment during acute exacerbations of COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2008;3:217–229. doi: 10.2147/copd.s1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El Sayed Zaki M., Raafat D., El Metaal A.A. Relevance of serology for Mycoplasma pneumoniae diagnosis compared with PCR and culture in acute exacerbation of bronchial asthma. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;131:74–80. doi: 10.1309/AJCP34YZGEHERWRX. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ou C.Y., Tseng Y.F., Chiou Y.H., Nong B.R., Huang Y.F., Hsieh K.S. The role of Mycoplasma pneumoniae in acute exacerbation of asthma in children. Acta Paediatr Taiwan. 2008;49:14–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanhan U., Orlowski J., Fiallos M. Association of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections with status asthmaticus. Open Respir Med J. 2008;2:35–38. doi: 10.2174/1874306400802010035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang Y.T., Yang Y.H., Chiang B.L. The significance of a rapid cold hemagglutination test for detecting mycoplasma infections in children with asthma exacerbation. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2006;39:28–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lehmann J.M., Holzmann B., Breitbart E.W., Schmiegelow P., Riethmüller G., Johnson J.P. Discrimination between benign and malignant cells of melanocytic lineage by two novel antigens, a glycoprotein with a molecular weight of 113,000 and a protein with a molecular weight of 76,000. Cancer Res. 1987;47:841–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lehmann J.M., Riethmüller G., Johnson J.P. MUC18, a marker of tumor progression in human melanoma, shows sequence similarity to the neural cell adhesion molecules of the immunoglobulin superfamily. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:9891–9895. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.24.9891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson J.P. Cell adhesion molecules in the development and progression of malignant melanoma. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1999;18:345–357. doi: 10.1023/a:1006304806799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shih I.M. The role of CD146 (Mel-CAM) in biology and pathology. J Pathol. 1999;189:4–11. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199909)189:1<4::AID-PATH332>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zigler M., Villares G.J., Lev D.C., Melnikova V.O., Bar-Eli M. Tumor immunotherapy in melanoma: strategies for overcoming mechanisms of resistance and escape. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:307–311. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200809050-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sers C., Riethmüller G., Johnson J.P. MUC18, a melanoma-progression associated molecule, and its potential role in tumor vascularization and hematogenous spread. Cancer Res. 1994;54:5689–5694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simon G.C., Martin R.J., Smith S., Thaikoottathil J., Bowler R.P., Barenkamp S.J., Chu H.W. Up-regulation of MUC18 in airway epithelial cells by IL-13: implications in bacterial adherence. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;44:606–613. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2010-0384OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schulz C., Petrig V., Wolf K., Krätzel K., Köhler M., Becker B., Pfeifer M. Upregulation of MCAM in primary bronchial epithelial cells from patients with COPD. Eur Respir J. 2003;22:450–456. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00102303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gross C.A., Bowler R.P., Green R.M., Weinberger A.R., Schnell C., Chu H.W. beta2-agonists promote host defense against bacterial infection in primary human bronchial epithelial cells. BMC Pulm Med. 2010;10:30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-10-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chu H.W., Kraft M., Krause J.E., Rex M.D., Martin R.J. Substance P and its receptor neurokinin 1 expression in asthmatic airways. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;106:713–722. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.109829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chu H.W., Halliday J.L., Martin R.J., Leung D.Y., Szefler S.J., Wenzel S.E. Collagen deposition in large airways may not differentiate severe asthma from milder forms of the disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158:1936–1944. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.6.9712073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chu H.W., Balzar S., Westcott J.Y., Trudeau J.B., Sun Y., Conrad D.J., Wenzel S.E. Expression and activation of 15-lipoxygenase pathway in severe asthma: relationship to eosinophilic phenotype and collagen deposition. Clin Exp Allergy. 2002;32:1558–1565. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2002.01477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chu H.W., Honour J.M., Rawlinson C.A., Harbeck R.J., Martin R.J. Effects of respiratory Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection on allergen-induced bronchial hyperresponsiveness and lung inflammation in mice. Infect Immun. 2003;71:1520–1526. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.3.1520-1526.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chu H.W., Jeyaseelan S., Rino J.G., Voelker D.R., Wexler R.B., Campbell K., Harbeck R.J., Martin R.J. TLR2 signaling is critical for Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced airway mucin expression. J Immunol. 2005;174:5713–5719. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.9.5713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chu H.W., Thaikoottathil J., Rino J.G., Zhang G., Wu Q., Moss T., Refaeli Y., Bowler R., Wenzel S.E., Chen Z., Zdunek J., Breed R., Young R., Allaire E., Martin R.J. Function and regulation of SPLUNC1 protein in Mycoplasma infection and allergic inflammation. J Immunol. 2007;179:3995–4002. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.3995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chu H.W., Campbell J.A., Rino J.G., Harbeck R.J., Martin R.J. Inhaled fluticasone propionate reduces concentration of Mycoplasma pneumoniae, inflammation, and bronchial hyperresponsiveness in lungs of mice. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:1119–1127. doi: 10.1086/382050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chu H.W., Breed R., Rino J.G., Harbeck R.J., Sills M.R., Martin R.J. Repeated respiratory Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections in mice: effect of host genetic background. Microbes Infect. 2006;8:1764–1772. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2006.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chu H.W., Balzar S., Seedorf G.J., Westcott J.Y., Trudeau J.B., Silkoff P., Wenzel S.E. Transforming growth factor-beta2 induces bronchial epithelial mucin expression in asthma. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:1097–1106. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63371-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Verstak B., Nagpal K., Bottomley S.P., Golenbock D.T., Hertzog P.J., Mansell A. MyD88 adapter-like (Mal)/TIRAP interaction with TRAF6 is critical for TLR2- and TLR4-mediated NF-kappaB proinflammatory responses. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:24192–24203. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.023044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Medvedev A.E., Kopydlowski K.M., Vogel S.N. Inhibition of lipopolysaccharide-induced signal transduction in endotoxin-tolerized mouse macrophages: dysregulation of cytokine, chemokine, and toll-like receptor 2 and 4 gene expression. J Immunol. 2000;164:5564–5574. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.11.5564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gimenez G., Magalhães K.G., Belaunzarán M.L., Poncini C.V., Lammel E.M., Gonzalez Cappa S.M., Bozza P.T., Isola E.L. Lipids from attenuated and virulent Babesia bovis strains induce differential TLR2-mediated macrophage activation. Mol Immunol. 2010;47:747–755. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pauwels R.A. Similarities and differences in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2004;1:73–76. doi: 10.1513/pats.2306024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu G.J., Varma V.A., Wu M.W., Wang S.W., Qu P., Yang H., Petros J.A., Lim S.D., Amin M.B. Expression of a human cell adhesion molecule, MUC18, in prostate cancer cell lines and tissues. Prostate. 2001;48:305–315. doi: 10.1002/pros.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dubin P.J., Kolls J.K. IL-23 mediates inflammatory responses to mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa lung infection in mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;292:L519–L528. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00312.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shimada K., Chen S., Dempsey P.W., Sorrentino R., Alsabeh R., Slepenkin A.V., Peterson E., Doherty T.M., Underhill D., Crother T.R., Arditi M. The NOD/RIP2 pathway is essential for host defenses against Chlamydophila pneumoniae lung infection. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000379. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000379. [Erratum appeared in PLoS Pathog 2009, 5 and in PLoS Pathog 2009 5] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]