Abstract

In the central nervous system, most synapses show a fast mode of neurotransmitter release known as synchronous release followed by a phase of asynchronous release, which extends over tens of milliseconds to seconds. Synapsin II (SYN2) is a member of the multigene synapsin family (SYN1/2/3) of synaptic vesicle phosphoproteins that modulate synaptic transmission and plasticity, and are mutated in epileptic patients. Here we report that inhibitory synapses of the dentate gyrus of Syn II knockout mice display an upregulation of synchronous neurotransmitter release and a concomitant loss of delayed asynchronous release. Syn II promotes γ-aminobutyric acid asynchronous release in a Ca2+-dependent manner by a functional interaction with presynaptic Ca2+ channels, revealing a new role in synaptic transmission for synapsins.

The arrival of action potentials at nerve terminals often leads to synchronous neurotransmitter release. Medrihan and colleagues use electrophysiology on mouse hippocampal neurons to show that the vesicle protein Synapsin II promotes GABAergic asynchronous release by interacting with calcium channels.

The arrival of action potentials at nerve terminals often leads to synchronous neurotransmitter release. Medrihan and colleagues use electrophysiology on mouse hippocampal neurons to show that the vesicle protein Synapsin II promotes GABAergic asynchronous release by interacting with calcium channels.

Neurotransmitter release is a tightly regulated process that allows neurons to communicate with each other. Most of the fast communication at the synaptic level is based on a synchronous process of neurotransmitter release in response to the action potential. However, the majority of CNS synapses also show an asynchronous component of neurotransmitter release following stimulation1,2,3,4,5,6,7. Asynchronous release is not fully time-locked to the presynaptic stimulus, is Ca2+-dependent, and is usually enhanced by the residual build-up of Ca2+ after repetitive stimulation5,7,8. Synaptotagmins, a family of presynaptic Ca2+-sensor proteins, have a fundamental role in the control of the synchronous and asynchronous modes of release, with distinct isoforms regulating different components of release9,10,11,12. Doc2, another presynaptic Ca2+ sensor, promotes asynchronous neurotransmitter release at excitatory synapses13 and VAMP4, a vesicle-associated SNARE protein, maintains asynchronous release at inhibitory synapses14.

Synapsins (Syn I, II and III) are a family of phosphoproteins that coat synaptic vesicles (SVs) and have important roles in neural development, synaptic transmission and plasticity15. The best described function of Syns is the control of neurotransmitter release by clustering SVs and tethering them to the actin cytoskeleton, thus maintaining the integrity of the reserve SV pool15,16. Moreover, at least in inhibitory synapses, Syns appear to control downstream events of SV exocytosis, such as docking and fusion and, implicitly, the size of the readily releasable pool (RRP)16,17. Mutant mice lacking one or more Syn isoforms are all prone to epileptic seizures, with the exception of Syn III knockout (KO) mice15,18. Genetic mapping analysis identified SYN2 among a restricted number of genes significantly contributing to epilepsy predisposition19,20 and mutations in the SYN1 gene have been reported to have a causal role in epilepsy and/or autism21,22. Synapsin II appears to have a specific role in preventing synaptic depression and maintaining the reserve pool of SV at central excitatory synapses and neuromuscular junction23,24,25, but its role in inhibitory synaptic transmission is not yet understood.

Here, we investigated the consequences of Syn II deletion on basal neurotransmitter release and short-term plasticity at hippocampal inhibitory and excitatory synapses. The deletion of Syn II results in an increase of synchronous inhibitory transmission, while the asynchronous component of neurotransmitter release is virtually abolished selectively in inhibitory synapses. Moreover, we show that this action of Syn II is Ca2+-dependent and that Syn II interacts directly with presynaptic Ca2+ channels to modulate the ratio between synchronous and asynchronous GABA (γ-aminobutyric acid) release.

Results

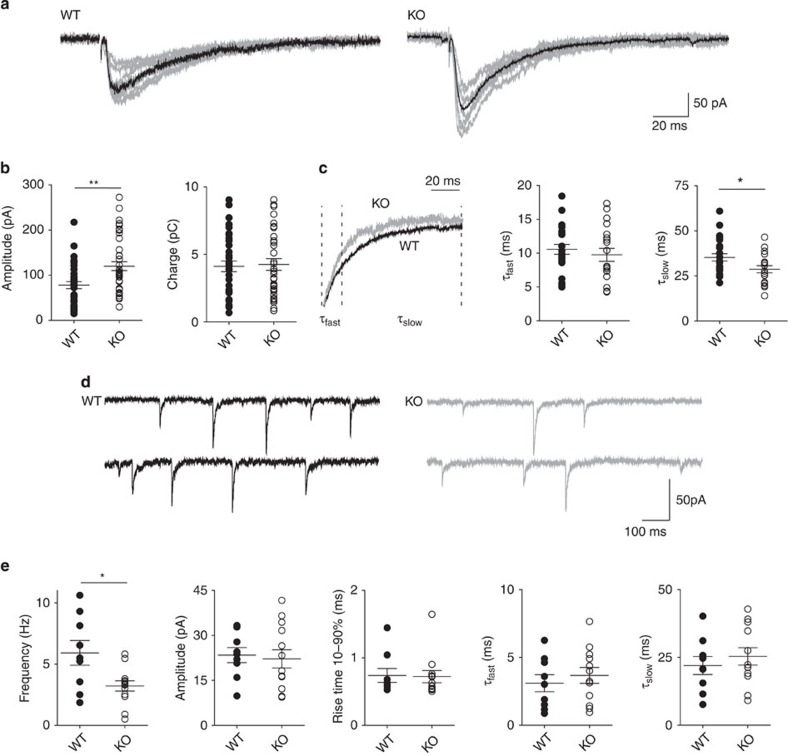

Post-docking roles of Syn II at inhibitory synapses

We first investigated the functional effects of Syn II deletion on neurotransmitter release at both inhibitory and excitatory synapses. To this purpose, we made whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings of dentate gyrus granule neurons in hippocampal slices of 3-week-old Syn II KO and age-matched WT mice. We employed extracellular stimulation (see Methods) of the medial perforant path to elicit monosynaptic inhibitory26 (Supplementary Fig. S1) or excitatory (Supplementary Fig. S2) responses in granule cells. While no changes were observed in the evoked excitatory postsynaptic currents (Supplementary Fig. S2), the amplitude of evoked inhibitory postsynaptic currents (eIPSCs) was significantly higher in KO neurons (78.14±7.83 pA; n=36 neurons/17 mice for WT neurons; 120.11±9.85 pA, n=39 neurons/20 mice for KO neurons; P=0.001) (Fig. 1a). This increase in amplitude was not accompanied by changes in the total area of the response (4.11±0.39 and 4.24±0.43 pC, for WT and KO neurons, respectively, P=0.52) (Fig. 1b), suggesting alterations in the kinetics of release. By fitting the deactivation time-course of the eIPSCs with a biexponential function, we observed that the fast component (τfast) of the response was unchanged between genotypes (10.57±0.72 and 9.75±0.97 ms, for WT and KO neurons, respectively, P=0.49), whereas the slow component (τslow) of the decay was significantly faster in KO neurons (35.29±2.01 and 28.75±1.92 ms, for WT and KO neurons, respectively, P=0.029) (Fig. 1c). This effect can explain the apparent inconsistency between the lack of difference in the total charge and the clear increase of the eIPSC amplitude (Fig. 1b).

Figure 1. Syn II deletion modifies the dynamics of the evoked GABA response.

(a) Representative traces of eIPSCs from WT and KO dentate gyrus granule neurons (the average trace is shown in black). (b) Mean (±s.e.m.) amplitude and charge of eIPSCs (closed and open circles represent single experiments for WT and KO neurons, respectively). (c) The decay of the WT eIPSC (left panel; black trace) was normalized to the peak amplitude of the KO eIPSC (grey trace). A two-exponential model was used to fit the fast and slow components of the decay (τfast and τslow) and their average values (±s.e.m.) are shown in the middle and right panels, respectively. *P<0.05, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test. n=23 and n=30 neurons for WT (10 mice) and KO (15 mice), respectively. Analysis of eIPSC kinetics showed that the latency (2.06±0.19 and 1.78±0.28 ms, for WT and KO neurons, respectively, P=0.45) and rise time (2.74±0.34 and 2.85±0.32 ms, for WT and KO neurons, respectively, P=0.81) were similar between genotypes (data not shown). (d) Representative traces of mIPSCs recorded in dentate gyrus granule neurons from WT (black) and KO (grey) mice. (e) Aligned dot plots of frequency, amplitude and kinetic parameters (rise time; τfast; τslow ) of mIPSCs in neurons from WT (closed symbols) and KO (open symbols) mice. Each dot represents one experiment. *P<0.05, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test. n=9 and n=13 neurons from WT (4 mice) and KO (6 mice), respectively.

Differences in the amplitude and kinetics of the inhibitory response may have a postsynaptic origin, as changes in the subunit composition of GABAA receptors can influence both parameters27. To clarify this matter, we recorded miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents (mIPSCs) from granule neurons in the presence of 0.3 μM TTX. We noticed a reduction in the frequency of mIPSCs in KO neurons (5.91±1.00 and 3.18±0.42 Hz, for WT and KO neurons, respectively; P=0.011; Fig. 1d), pointing to a presynaptic defect. Neither amplitude (23.43±2.51 and 22.19±3.04 pA, for WT and KO neurons, respectively, P=0.75) nor kinetics of mIPSCs (rise time 10–90%: 0.73±0.10 and 0.72±0.09 ms, P=0.90; τfast: 3.09±0.62 and 3.67±0.58 ms, P=0.516; τslow: 22.01±3.33 and 25.40±3.20 ms, P=0.48; n=9 neurons/4 mice and n=13 neurons/6 mice for WT and KO neurons, respectively) were modified between genotypes, suggesting a normal postsynaptic function in KO mice (Fig. 1d). The slower decay kinetics of evoked responses with respect to the miniature currents in WT neurons has been previously attributed to higher level of asynchronous vesicle release28. Thus, these data suggest that the absence of Syn II favours synchronous release at dentate gyrus inhibitory synapses.

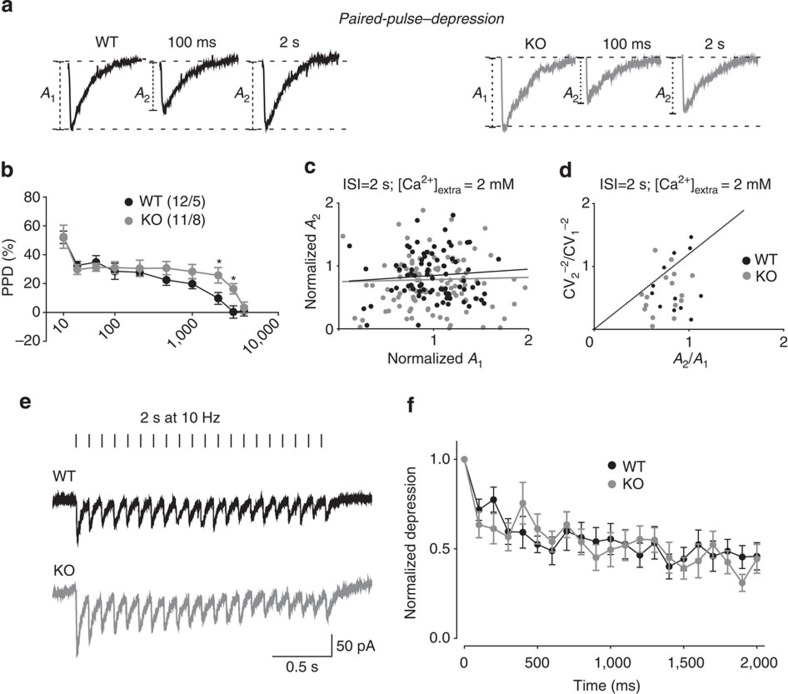

Short-term plasticity in Syn II KO neurons

The data reported in Fig. 1 suggest that SVs in inhibitory nerve terminals of KO mice are more prone to undergo exocytosis in response to a sudden increase in Ca2+ following the action potential. We tested this possibility by using a paired-pulse stimulation protocol, which is tightly affected by changes in the intraterminal Ca2+ concentration29,30. The paired-pulse depression (PPD) induced at short inter-stimulus intervals (ISIs) was similar between genotypes at short ISIs, but it significantly increased in KOs when ISIs were increased to 2 or 3 s (Fig. 2a). PPD at short ISIs (PPDfast) is highly dependent on Ca2+, while at longer ISIs (PPDslow) the Ca2+-dependence is progressively lost29. Thus, the more intense PPDslow observed in the KO slices, could result from a larger depletio of the SV pool induced by the first stimulation, whose amplitude was larger in KO than in WT neurons. To evaluate this possibility, we compared the normalized amplitudes of the first and second responses at 2-s ISI29,31 (Fig. 2c) and further evaluated synaptic depression in response to different trains of stimuli (Figs 2e and 3a). The lack of correlation between the two parameters suggests that the depression of the second eIPSC is independent of the amount of SVs released by the first stimulus (Fig. 2c). Next, we investigated whether PPD had either a presynaptic or postsynaptic origin. The variation in the peak current amplitude during the first and second IPSCs was evaluated for inter-pulse intervals of 2 and 3 s (12 pairs for WT and 16 pairs for KO using an analysis developed by Malinow and Tsien31,32 (see Methods). Figure 2d shows a summary plot of the inverse of the square of the CV (CV−2) versus the mean amplitude of the second response, both normalized to the values of the first IPSC for both WT and KO neurons. Most of the experimental points fell under the identity line, indicating a presynaptic origin of the increased PPDslow observed in KO slices. Several studies report that the lack of Syns causes higher depression in response to various stimulation frequencies in both excitatory and inhibitory synapses17,25. In contrast, we observed that Syn II deletion had no effects on synaptic depression induced by stimulation at either 10 or 40 Hz in both inhibitory (Figs 2e, f and ) and excitatory (Supplementary Fig. S3a–c) synapses.

Figure 2. Syn II deletion does not induce major changes in short-term plasticity at inhibitory synapses.

(a) Representative dual eIPSCs traces recorded from dentate gyrus WT (black) and KO (grey) neurons in response to paired stimulation of the medial perforant path at the indicated ISIs. (b) The mean per cent (±s.e.m.) PPD observed in WT (black symbols; n=8–12) and KO (grey symbols; n=6–13) neurons is plotted as a function of the ISI. (c) Plot of the amplitude of the response to the second pulse (A2) versus the amplitude of the response to the first pulse (A1) (10 responses/neuron from n=13 KO and 12 WT neurons,) at 2-s ISI in 2 mM Ca2+. Both amplitudes are normalized to the mean A1 in the recorded ensemble. Linear regression analysis of the data points (black and grey lines for WT and KO, respectively) shows no significant correlation between A1 and A2. (d) The inverse of the square coefficient of variation (CV−2) of the second IPSC (A2) normalized by the CV1 of the first IPSC (A1) was plotted against the PPR (A2/A1) (n=12 and n=16 pairs of WT and KO neurons stimulated at 2 s ISI, respectively). Note that most of the data points of both WT and KO neurons fall below the unitary line, indicating a presynaptic mechanism of short-term depression. (e) Representative traces from WT (black) and KO (grey) in response to stimulation of the medial perforant path for 2 s at 10 Hz. (f) Plot of normalized peak amplitude (±s.e.m.) versus time showing the multiple-pulse depression at 10 Hz in WT (black) and KO (grey) neurons.

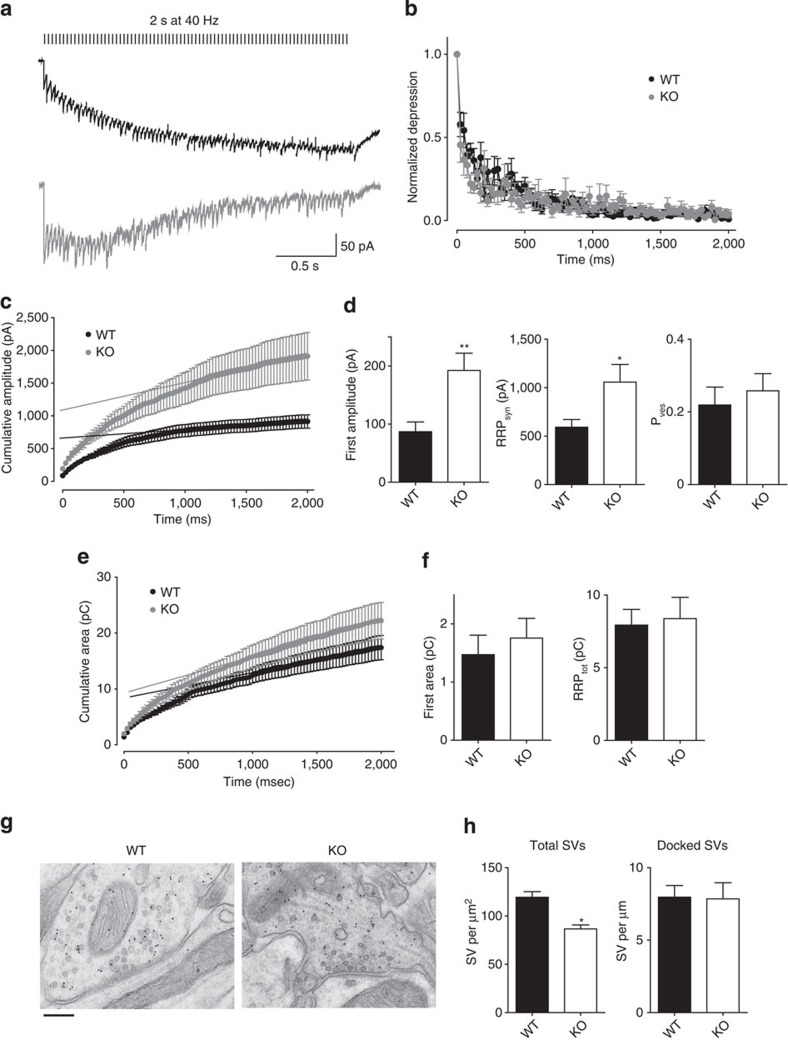

Figure 3. Syn II deletion increases the RRP size of synchronously released GABA vesicles.

(a) Representative responses from WT (black) and KO (grey) neurons induced by stimulation of the medial perforant path for 2 s at 40 Hz. Stimulation artifacts were removed for clarity. (b) Plot of the normalized amplitude (means±s.e.m.) versus time showing the multiple-pulse depression during the 40-Hz train in WT (black) and KO (grey) neurons. (c) Cumulative amplitude profile of a 2-s train at 40 Hz. Data points from the last second of the response were fitted by linear regression and the line was extrapolated to time 0 to estimate the RRPsyn. (d) Mean values (±s.e.m.) of the amplitude of the first eIPSC in the train, RRPsyn and Pves for WT (black bars) and KO (open bars) neurons. (e) Cumulative area profile of a 2-s train at 40 Hz. Data points from the last second of the response were fitted by linear regression and the line was extrapolated to time 0 to estimate the RRPtot. (f) Mean values (±s.e.m.) of the first eIPSC area in the train and RRPtot for WT (black bars) and KO (open bars) neurons. For electrophysiology experiments: **P<0.01, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test and *P<0.05, Welch’s t-test. n=16 and n=14 neurons from WT (5 mice) and KO (8 mice), respectively. (g) Micrographs of GABA-immunopositive synaptic terminals (stained by 10 nm gold particles) making contact with granule cell dendrites in the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus of WT and KO slices. Scale bar, 200 nm. (h) Mean values (±s.e.m.) of the density of total SVs and the number of docked SVs in presynaptic terminals of WT (black bars) and KO (open bars) neurons. For EM experiments: *P<0.05, unpaired Student’s t-test; n=100/39 synapses from 4 WT mice and 69/72 synapses from 4 KO mice.

Syn II deletion enhances the synchronous RRP

Based on the previous observations, we then investigated the properties of the synchronous and asynchronous GABA release by using high-frequency stimulation. By analysing the cumulative amplitude profile during a high-frequency train (2 s at 40 Hz; Fig. 3c), we observed a larger amplitude of the first response in the train in KO neurons (86.86±16.86, n=16 neurons/5 mice and 192.3±29.56 pA; n=14 neurons/8 mice for WT and KO neurons, respectively, P=0.003; Fig. 3d). Such increase of the synchronous response is due to an increase in the readily releasable pool size (RRPsyn) (591.8±79.5 versus 1,058.0±181.9 pA, for WT and KO neurons respectively, P=0.02) and not to a change in the vesicular release probability (Pves) (0.21±0.04 versus 0.25±0.04, for WT and KO neurons respectively, P=0.56; Fig. 3d). We further studied the quantal parameters of inhibitory synaptic transmission using the multiple fluctuation probability analysis17. This method (Supplementary Methods), that provides direct information on the average quantal release probability (Prav), number of independent release sites (Nmin) and average postsynaptic quantal size (Qav), fully confirmed the data obtained by the cumulative amplitude analysis indicating that an increase in Nmin is responsible for the increased eIPSC amplitude (Supplementary Fig. S4). However, the RRP size determined with these methods is an underestimation of the total RRP, as it represents only the synchronously released part of SVs33. The cumulative area method gives a better estimation of the total RRP33, as it includes also the asynchronous component of the response (Fig. 3e). Not only the area of the first response of the train did not change between genotypes (1.47±0.33 and 1.75±0.33 pC, for WT and KO neurons, respectively, P=0.55) (Figs 3f and 1b), but also the RRPtot, measured with the cumulative area method, resulted similar between genotypes (7.93±1.07 and 8.37±1.46 pC, for WT and KO neurons, respectively, P=0.80; Fig. 3f).

We next used electron microscopy (Supplementary Methods) to morphologically evaluate the number and spatial distribution of SVs within the inhibitory GABA-immunopositive terminals in the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus of KO and WT slices (Fig. 4g). The total density of SVs was significantly decreased in KO synapses (120.8±9.1, n=100 terminals/4 mice and 88.2±3.9 SVs per μm2, n=69 terminals/4 mice, for WT and KO, respectively, P=0.016; Fig. 3g). However, the number of docked SVs, putatively corresponding to the functional RRP34, did not differ between genotypes (7.97±0.80, n=39 terminals/4 mice, and 7.85±1.11 SVs per μm, n=72 terminals/4 mice, for WT and KO, respectively, P=0.93) (Fig. 3g). Together, these results strengthen the indication that the synchronous and asynchronous release appear to compete for a common pool of release-ready SVs35 and that the ratio between the two modalities of release is modified in the absence of Syn II.

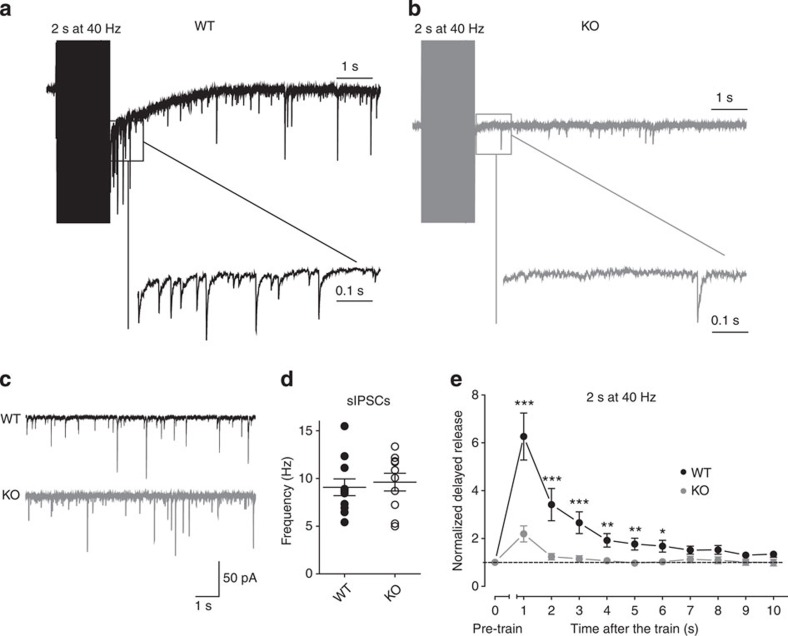

Figure 4. Syn II deletion dramatically reduces the delayed asynchronous GABA release.

(a,b) Representative traces of the inhibitory delayed asynchronous response in WT (a; black) and KO (b; grey) dentate gyrus granule cells after stimulation of the medial perforant path. Inset traces represent the first second after the end of the stimulation. (c) Representative traces of sIPSCs recorded in dentate gyrus granule neurons from WT (black) and KO (grey) mice. (d) Frequency (means±s.e.m.) of sIPSC measured at −80 mV in the presence of 50 μM D-APV, 10 μM CNQX, 5 μM CGP 55845 (n=11 and n=10 neurons from 5 WT mice and 9 KO mice, respectively). Each dot represents a single experiment. (e) Plot of the mean (±s.e.m.) charge of the delayed GABA release as a function of time after the end of the stimulation train. Data (black and grey symbols/lines for WT and KO, respectively) were normalized to the pre-train spontaneous release. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001, Welch’s t-test. n=26 and n=24 neurons from WT (10 mice) and KO (12 mice), respectively.

Delayed asynchronous release is reduced in Syn II KO mice

High-frequency stimulation trains lead to delayed asynchronous release that persists for tens/hundreds of milliseconds to seconds in excitatory and inhibitory synapses4,5,7,36. Thus, we measured the delayed asynchronous release in response to trains of 40 Hz (Fig. 4a). The extent of spontaneous network activity preceding the application of the train may influence the amount of asynchronous release induced by the train. To eliminate this possibility, we measured the frequency of spontaneous IPSCs (sIPSCs) before the train stimulus, and observed similar values in the two genotypes (9.07±0.87, n=11 neurons/5 mice and 9.61±0.93, n=10 neurons/9 mice for WT and KO neurons, respectively, P=0.67; Fig. 4c). WT synapses showed enhanced asynchronous release after the train that slowly returned to baseline within 10 s, while in KO synapses the asynchronous release was tenfold lower and returned to baseline value within 2 s after the train (Fig. 4e). The delayed asynchronous release at excitatory synapses was not altered in KO neurons (Supplementary Fig. S3d), indicating the specificity of this phenotype for inhibitory synapses. The virtual absence of delayed asynchronous release of GABA may participate in the development of the strong epileptic phenotype of adult Syn II KO mice. Thus, we repeated the experiments in the dentate gyrus of adult symptomatic mice and found a closely similar depression of the delayed asynchronous release of GABA (Supplementary Fig. S5).

It was of interest to check whether Syn I, the most abundant Syn isoform, had any effect in the modulation of asynchronous release. Interestingly, we observed that Syn I deletion increased the asynchronous release in inhibitory synapses of primary hippocampal neurons, conforming with a non-redundant function of Syn I on release dynamics that is opposite to that of Syn II (Supplementary Fig. S6). Moreover, the increase in the asynchronous response of Syn I KO inhibitory neurons was associated with decreased eIPSC amplitude and RRP size17, which are opposite respect to the changes observed in Syn II KO neurons (Figs 1 and 3).

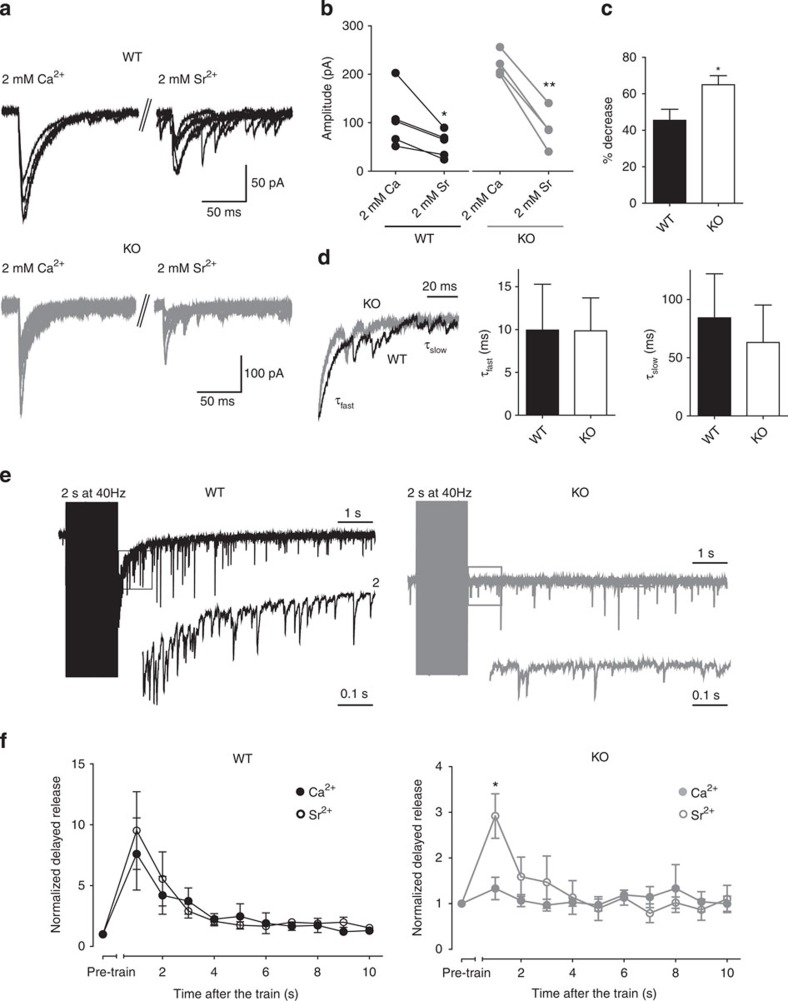

Syn II modulates release in a Ca2+-dependent manner

Both synchronous and asynchronous release are Ca2+-dependent, but they are likely to be mediated by two distinct Ca2+ sensors with different Ca2+ affinities: a low-affinity sensor that sustains fast synchronous release and a high-affinity sensor that is involved in the slow asynchronous release7,8. We attempted to experimentally desynchronize the inhibitory synaptic transmission by replacing extracellular Ca2+ with Sr2+, as the distinct Ca2+ sensors have the same affinity for Sr2+ (4,37,38,39). In the single-pulse protocol, Sr2+ (2 mM) induced a reduction in the peak amplitude of the synchronous current in both WT (106.31±26.36 versus 56.42±12.06 pA, P=0.018, n=5 neurons/3 mice) and KO neurons (245.62±37.16 versus 87.99±20.49 pA, P=0.005, n=4 neurons/3 mice) (Fig. 5a). However, the per cent reduction in the peak amplitude induced by Sr2+ was higher in KO than in WT neurons (45.48±6.050% and 64.99±4.997%, for WT and KO, respectively, P=0.047; Fig. 5c). Also, the fast component (τfast) of the response in Sr2+ had similar values as in Ca2+ and was unchanged between genotypes (9.94±5.35 and 9.85±3.84 ms for WT and KO neurons, respectively, P=0.99), while the slow component (τslow) of the decay was significantly slower in Sr2+, yet still unchanged between WT and KO neurons (84.27±37.78 and 63.11±32.16 ms, for WT and KO neurons, respectively, P=0.69; Fig. 5d). Changing the extracellular solution from Ca2+ to Sr2+ severely desynchronized the sIPSCs in both WT and KO neurons, but when high-frequency stimulation trains were applied in the presence of Sr2+, a significant increase in the delayed asynchronous release was observed only in KO neurons (Fig. 5e).

Figure 5. Ca2+-dependency of delayed asynchronous GABA release in Syn II KO neurons.

(a) Representative traces of eIPSCs from the same WT (black) and KO (grey) dentate gyrus granule neurons in 2 mM Ca2+ and after replacement of Ca2+ with 2 mM Sr2+. (b) Plot of the peak amplitude of eIPSCs before and after the switch to 2 mM Sr2+ for WT (black) and KO (grey) neurons. (c) Mean values (±s.e.m.) of the per cent depression in the peak eIPSC amplitude for WT and KO neurons (closed and open bars, respectively) after replacement of Ca2+ with Sr2+. (d) Representative traces of the eIPSC decay. The trace recorded in WT neurons (black) was normalized to the peak amplitude of eIPSC in KO neurons (grey trace) in 2 mM Sr2+. A two-exponential model was used to fit the fast and the slow components of the decay (τfast and τslow). *P<0.05 and **P<0.01, two-tailed paired (b) and unpaired (c) Student’s t-test. n=5 and n=4 neurons from WT (3 mice) and KO (3 mice), respectively. (e) Representative traces of the delayed asynchronous inhibitory response in 2 mM Sr2+ recorded in WT (black) and KO (grey) dentate gyrus granule neurons after stimulation of the medial perforant path. Inset traces represent the first second after the end of the stimulation. (f) Plots of the mean (±s.e.m.) charge of the delayed asynchronous release as a function of time after the end of the stimulation train in WT and KO neurons. Data recorded in the presence of either 2 mM Ca2+ (closed symbols) or 2 mM Sr2+ (open symbols) were normalized to the respective pre-train spontaneous release. *P<0.05, two-tailed paired Student’s t-test n=11 and n=4 neurons from WT (3 mice) and KO (3 mice), respectively.

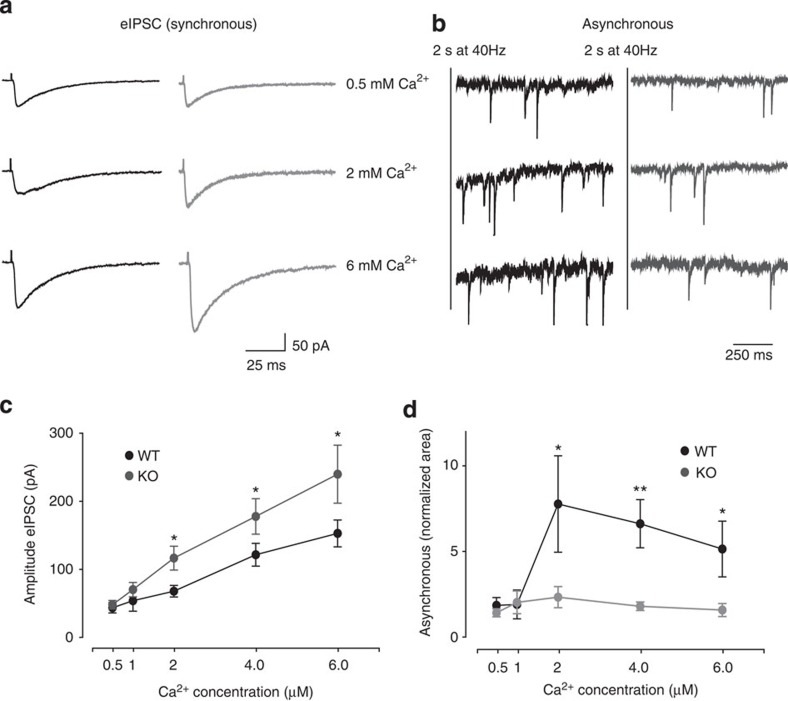

To further confirm the Ca2+ dependency of the Syn II, we analysed the amplitude of the evoked response and the delayed asynchronous release in different extracellular Ca2+ concentrations (Fig. 6). At low Ca2+ concentrations, (0.5 and 1 mM) both the eIPSC amplitude and the delayed asynchronous release (measured here only for the first second after the train for simplicity) were not changed between WT and KO mice (Fig. 6a). However, a clearly distinct behaviour of the analysed parameters was observed at higher Ca2+ (4 and 6 mM). While the amplitude of eIPSC increased linearly with the Ca2+ concentration in the KO mice, remaining significantly higher than the WT (Fig. 6c), the delayed asynchronous response of KO neurons remained at basal levels and was completely insensitive to the increasing Ca2+ concentration (Fig. 6d). On the contrary, short-term plasticity in WT and KO inhibitory responses was not affected by the different Ca2+ levels (Supplementary Fig. S7). Taken together, these data further demonstrate that the absence of Syn II from inhibitory synapses abolishes the delayed asynchronous release in favour of evoked synchronous release.

Figure 6. Syn II deletion modulates the synchronous/asynchronous release in a Ca2+-dependent manner.

(a) Representative traces of eIPSCs from WT (black) and KO (grey) dentate gyrus neurons at low (0.5 mM), normal (2 mM) and high (6 mM) extracellular Ca2+ concentrations. (b) Representative traces of the first second after a 2-s train at 40 Hz from WT (black) and KO (grey) neurons at different Ca2+ concentrations. (c,d) eIPSCs peak amplitude (c) and normalized area of the first second after the train (d) in WT and KO slices as a function of the increasing extracellular Ca2+ concentration. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, Welch’s t-test. n=10 neurons/6 mice for WT and n=9 neurons/5 mice for KO.

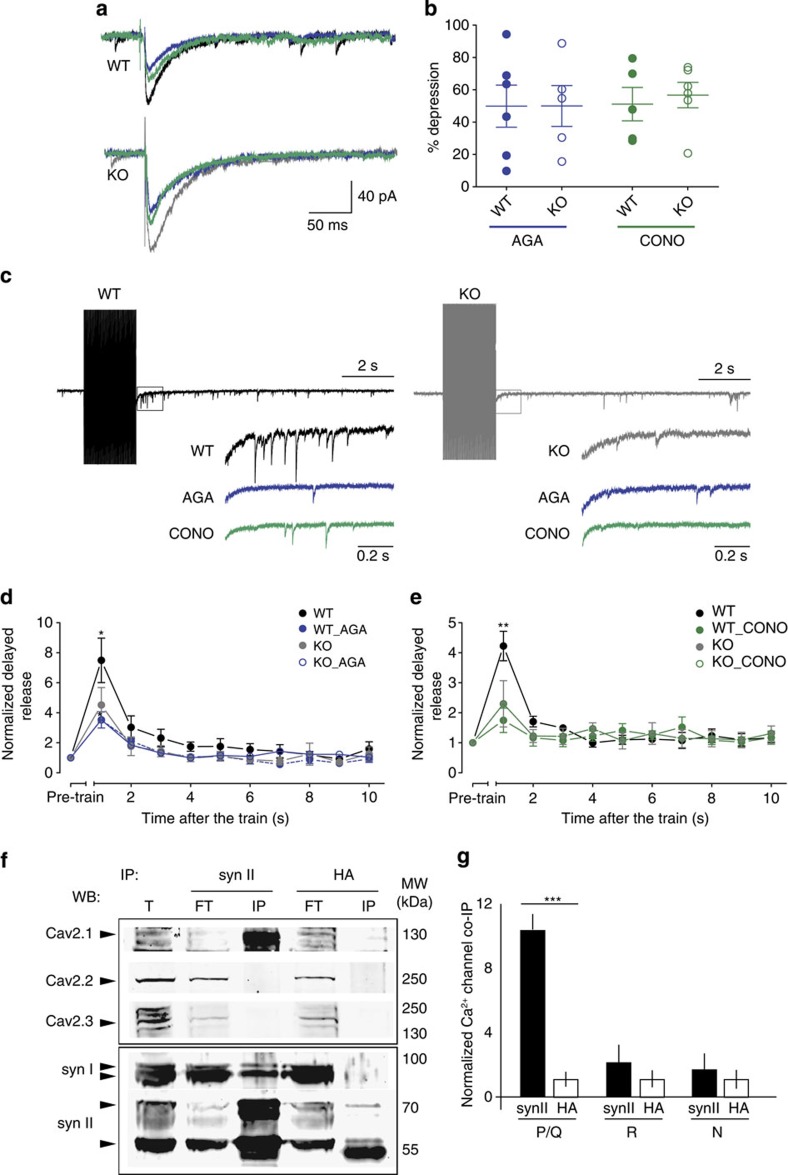

Syn II interacts with Ca2+ channels to modulate GABA release

While Syn I displays a Ca2+-binding site involving a glutamate residue (E373), Syn II does not share this key acidic residue indispensable for Ca2+ coordination and has a basic residue instead (K374)40. On this basis, Syn II is predicted not to bind Ca2+ and, accordingly, ATP binding to Syn II is not Ca2+-dependent40. Thus, Syn II cannot theoretically control asynchronous release by direct binding of Ca2+. However, recent data by proteomics41 reported that Syn I and Syn II may interact with Ca2+ channels. To confirm this possibility, we performed functional experiments with blockers of distinct subtypes of presynaptic Ca2+ currents. Addition of ω-Agatoxin-IVA, a blocker of P/Q-type Ca2+ currents, reduced the peak amplitude of the GABA synchronous response by 50% in both phenotypes (49.9±13.04% and 50.0±12.64%, n=6 neurons/4 mice and n=5 neurons/4 mice for WT and KO, respectively, P=0.99; Fig. 7a). Similarly, addition of ω-Conotoxin-GVIA, a blocker of N-type Ca2+ currents, caused a similar ~50% reduction in the amplitude of the GABA synchronous current in both WT and KO neurons (51±10.33% and 56.75±7.98%, n=5 neurons/5 mice and n=6 neurons/3 mice for WT and KO, respectively, P=0.670; Fig. 7a). Importantly, neither ω-Agatoxin-IVA nor ω-Conotoxin-GVIA had any effect on the delayed asynchronous release in Syn II KO neurons, but reduced it significantly in WT slices (Fig. 7c–e). To further support these functional data, we performed co-immunoprecipitation experiments on cortical neuron lysates, using anti-Syn I and anti-Syn II antibodies. While no interaction was present between Syn II and Cav2.2 (N-type)/ Cav2.3 (R-type) channels, a specific interaction was detected between Syn II and Cav2.1 (P/Q-type; Fig. 7f). Interestingly, the interaction appeared to be specific for Syn II, as virtually no interaction between Syn I and all tested Ca2+ channels was detected (Supplementary Fig. S8). Taken together, these data suggest that Syn II controls the amount of asynchronous release at inhibitory synapses through an interaction with a specific subtype of Ca2+ channels.

Figure 7. Syn II modulates GABA asynchronous release by interacting with presynaptic Ca2+ channels.

(a) Representative traces of eIPSCs from WT and KO dentate gyrus granule neurons before (black and grey for WT and KO, respectively) and after blockade of P/Q-type Ca2+ current with 0.5 μM ω-Agatoxin-IVA (blue) or of N-type Ca2+ current with 1 μM ω-Conotoxin-GVIA (green). (b) Aligned dot plot of the per cent reduction in peak amplitude of eIPSCs in WT (closed circles) and KO (open circles) neurons after the addition of either ω-Agatoxin-IVA (AGA; 0.5 μM) or ω-Conotoxin-GVIA (CONO; 1 μM). (c) Representative traces of the delayed asynchronous inhibitory response in WT and KO neurons (black and grey, respectively) and its modulation by Ca2+-channel blockers. Inset traces represent the first second after the end of the stimulation under control conditions and after the addition of ω-Agatoxin-IVA (0.5 μM; blue) or ω-Conotoxin-GVIA (1 μM; green). (d) Plots of the mean (±s.e.m.) charge of the delayed asynchronous release as a function of time after the end of the stimulation train in WT and KO neurons. Data recorded under control conditions (black/grey circles) or in the presence of ω-Agatoxin-IVA (0.5 μM; closed/open blue circles) were normalized to the respective pre-train spontaneous release. *P<0.05, two-tailed paired Student’s t-test. n=5 neurons from both WT (4 mice) and KO (4 mice), respectively. (e) Same as for d, but in the presence of ω-Conotoxin-GVIA (1 μM; closed/open green circles) **P<0.01, two-tailed paired Student’s t-test. n=5 and n=6 neurons from WT (4 mice) and KO (3 mice), respectively. (f,g) Cortical neuron lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-SynII antibodies or anti-HA antibodies, as indicated (immunoprecipitation (IP)). After electrophoretic separation of the immunocomplexes, membranes were probed with antibodies specific for anti-Cav2.1 (P/Q-type), anti-Cav2.2 (N-type) and anti-Cav2.3 (R-type) Ca2+ channel subunits, as indicated (western blotting (WB)). A representative immunoblot is shown (f), together with the quantification of the immunoreactive signal in the immunoprecipitated samples (g), normalized to the binding to the HA control (means±s.e.m.; n=3 independent experiments). T, 100 μg of total lysate; FT, 100 μg of flow-through after immunoprecipitation.

Discussion

We examined the dynamics of basal neurotransmitter release and short-term plasticity in mouse hippocampal inhibitory synapses lacking Syn II. For the first time, we report that Syn II has a specific post-docking role in inhibitory synapses, influencing basal GABA release and leading to subtle changes in short-term plasticity (Figs 1, 2 and 3). More importantly, Syn II appears to modify the dynamics of GABA release by promoting asynchronous SV release at the expense of synchronous release (Fig. 4). Finally, we demonstrate that Syn II interacts with presynaptic Ca2+ channels to promote GABA asynchronous release (Figs 5, 6 and 7).

Inhibitory synapses lacking Syn I, Syn III or all three Syn isoforms show a decrease in the amplitude of the IPSCs evoked by single action potentials16,17,42,43. We have found that the deletion of Syn II increases the peak amplitude of evoked responses and reduces the frequency of the mIPSCs at hippocampal inhibitory synapses. Opposite to the findings from Syn I KO mice in which synaptic depression at inhibitory synapses was enhanced17, the Syn II deletion lead to no changes in synaptic depression and minute changes in PPD. These data suggest that the various Syn isoforms are endowed with distinct post-docking functions at inhibitory synapses.

The increased inhibitory response to single stimulation in Syn II KO neurons appears to be induced by acceleration of the dynamics of GABA release. Deletion of SYN2 strongly enhanced synchronous SV release, while the delayed asynchronous release was virtually abolished. These results imply that the function of Syn II is to desynchronize SV release, opposite to Syn I that was hypothesized to facilitate release synchronization44,45. Indeed, we found that deletion of Syn I increased the asynchronous release in inhibitory synapses, an effect opposite to that of Syn II deletion. Thus, the possibility exists that Syns I and II have non-redundant functions and constitute a push–pull mechanism regulating the ratio between synchronous and asynchronous release in the synapses in which they are co-expressed.

An important question is how Syn II changes the ratio between synchronous and asynchronous neurotransmitter release. As both Syn I and Syn II do not apparently affect the pool of docked SVs, we suggest that they might directly affect downstream exocytotic events and regulate the dynamics of release. The synchronous release has been so far connected with members of the synaptotagmin family of Ca2+ sensors9,10,11. Synaptotagmin-1 or synaptotagmin-2 deletions lead to a complete loss of synchronous release at both excitatory and inhibitory synapses9,10,11, while asynchronous release is preserved and even enhanced at high stimulation frequencies10. The knockdown of synaptotagmin-7 at the zebrafish neuromuscular junction reduces asynchronous release46, however it has no effect on synchronous/asynchronous release in central synapses47. We detected no interaction of either Syn I or Syn II with the various synaptotagmin isoforms (−1, −2 and −7) in coimmunoprecipitation experiments (data not shown), suggesting that the accelerated neurotransmitter release in Syn KO II slices is independent of a possible impairment of the synaptotagmin normal function. On the other hand, the mechanisms behind asynchronous release are still far from being understood, with recent work proposing several hypotheses. One proposed mechanism involves a slow presynaptic Ca2+ sensor, Doc2, that binds Ca2+ with slower kinetics and its knockdown in hippocampal cultures results in reduced asynchronous release48. Another recent paper reports that the SNARE protein VAMP2 drives synchronous release, while its isoform VAMP4 boosts asynchronous release14. Moreover, it was recently shown that both voltage-gated presynaptic Cav-2.1 and Cav-2.2 channels, that conduct P/Q-type and N-type Ca2+ currents respectively, are characterized by a prolonged Ca2+ current that promotes asynchronous release49.

The sensitivity of both evoked synchronous and delayed asynchronous release to Sr2+ versus Ca2+ and to various concentrations of extracellular Ca2+ in Syn II KO slices supports the idea that the postdocking functions of Syn II are Ca2+ dependent. One possible explanation for this Ca2+-dependency is that Syns modulate neurotransmitter release by coupling SVs with presynaptic Ca2+ channels. Indeed, several studies demonstrated that Ca2+ channels are tightly coupled with SVs in the nanodomain range50 and, in addition, a potential interaction between Syn I and Syn II with distinct Ca2+ channel subunits was recently reported by means of proteomics41. In our experiments, addition of blockers of either P/Q- or N-type of Ca2+ currents reduced the synchronously evoked and delayed asynchronous current in WT slices, but the delayed asynchronous release was not affected by both Ca2+-channel blockers in Syn II KO slices. Our patch-clamp experiments were performed at non-specific hippocampal inhibitory synapses, where at least a subset includes output synapses from interneurons expressing P/Q or N-type Ca2+ channels, as Ca2+ channels are interneuron specific2,50.

Interestingly, we found for the first time that, Syn II specifically interacts with Cav-2.1 type Ca2+ channels, but not with Cav-2.2 or Cav-2.3 types, while Syn I does not co-immunoprecipitate with any of the main presynaptic Ca2+-channel subunits, indicating a physiologically important and non-redundant function of Syn II with respect to Syn I. We cannot exclude that the interaction between Syn II and Cav-2.1 type Ca2+-channels is indirect and mediated by modulatory proteins of the active zone, such as via the Rab3-RIM-Ca2+-channel pathway. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that Syns interact with Rab351,52 and may thereby interfere with RIM binding to N and P/Q-type Ca2+ channels at the active zone53, decreasing the efficiency, speed and synchrony of release. As Syn II appears to bind more tightly to SVs than Syn I (F. Benfenati, unpublished observations), it is possible that Syn II remains to a large extent attached to SVs during the post-docking steps of release, possibly acting as a brake for the synchronous release of SVs docked in the vicinity of a specific Ca2+ channel. The genetic deletion of Syn II may decrease the physical distance between Ca2+ channels and SVs at GABAergic synapses, thus speeding up neurotransmitter release with respect to the incoming action potential. Under these conditions, if a train of action potentials invades the presynaptic site, then the SVs available for release are more rapidly exhausted, thus explaining the lack of delayed asynchronous release in the Syn II KO neurons. Although Syn II specifically interacts only with P/Q-type Ca2+ channels, its deletion occluded the effects of both P/Q- and N-type Ca2+ channel blockers. This suggests that the Syn II effect on the asynchronous release is downstream of the asynchronous Ca2+ current, and that both types of channels contribute to the bulk intraterminal Ca2+ that drives asynchronous release.

Strikingly, the effect of Syn II deletion was restricted to inhibitory neurons, and no effects on release dynamics or short-term plasticity were observed in excitatory synapses. We demonstrated that, in inhibitory neurons, the effects of Syn II deletion on release dynamics occur only at physiological Ca2+ concentrations, while decreasing extracellular Ca2+ to decrease Pr virtually abolishes this phenotype (Fig. 6). It is therefore possible that the effects of Syn II on release dynamics require high Pr values and therefore emerge under physiological Ca2+ conditions in inhibitory synapses, but not in excitatory synapses that are characterized by significantly lower Pr values54,55.

This desynchronizing effect of Syn II on inhibitory synapses may have pathologic consequences, as Syn II KO mice are epileptic, with seizures starting after 2–3 months of life25,56. Changes in GABA asynchronous release between specific neurons from human epileptic and non-epileptic tissue have been recently reported57. After trains of APs or in some cases just one AP, long-lasting IPSCs generated by asynchronous GABA release occurring with significant delays can increase the effectiveness of inhibition58,59. Asynchronous GABA release apparently allows an inhibitory compensatory tuning proportional to the extent of presynaptic activity, and is markedly increased when synapses are stimulated with behaviourally relevant high-frequency patterns5,36. Interestingly, we have recently shown that presymptomatic Syn I/II/III KO mice display an impaired tonic current, due to defects in GABA release and spillover, leading to diffuse hyperexcitability of hippocampal pyramidal neurons42. It is tempting to speculate that the lack of asynchronous inhibitory release in the hippocampus of Syn II mice, by decreasing the tonic inhibition of excitatory neurons, directly contributes to the aberrant network synchronization and epileptogenesis.

Methods

Animals

Experiments were performed on homozygous Syn II KO mice generated by homologous recombination and age-matched C57BL/6J wild-type (WT) animals. All experiments were carried out in accordance with the guidelines established by the European Communities Council (Directive 2010/63/EU of 22 September 2010) and were approved by the Italian Ministry of Health.

Preparation of slices

After anaesthesia with isoflurane, horizontal hippocampal slices (400 μm thickness) from 3-week-old WT and KO mice were cut using a Microm HM 650 V microtome equipped with a Microm CU 65 cooling unit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) at 2 °C in a solution containing (in mM): 87 NaCl, 25 NaHCO3, 2.5 KCl, 0.5 CaCl2, 7 MgCl2, 25 glucose, 75 sucrose and saturated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. After cutting, we let the slices recover for 30–45 min at 35 °C and for 1 h at room temperature in recording solution.

Patch-clamp recordings

Whole-cell recordings were performed with a Multiclamp 700B/Digidata1440A system (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) on visually identified dentate granule cells using an upright BX51WI microscope (Olympus, Tokyo). We recorded mature dentate granule neurons in which Rm<300 MΩ26. The extracellular solution used for the recordings contained (mM): 125 NaCl, 25 NaHCO3, 25 glucose, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 2 CaCl2 and 1 MgCl2 (bubbled with 95% O2–5% CO2). In some experiments, CaCl2 was replaced with an equimolar concentration of SrCl2. For all experiments, we used a high-chloride intracellular solution containing (in mM): 126 KCl, 4 NaCl, 1 MgSO4, 0.02 CaCl2, 0.1 BAPTA, 15 glucose, 5 HEPES, 3 ATP and 0.1 GTP in which the pH was adjusted to 7.3 with KOH and osmolarity was adjusted to 290 mosmol l−1 with sucrose. Experiments were performed at room temperature apart from a subset of data (Fig. 6) performed at 34 °C. Recordings of evoked and spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic currents (eIPSCs and sIPSCs) were done at a holding potential (Vh) of −80 mV in the presence of 50 μM D-APV, 10 μM CNQX, 5 μM CGP 55845 (all from Tocris Bioscience, Ellisville, MO) and of mIPSCs after subsequently adding 0.3 μM TTX (Tocris Bioscience) to the above-mentioned drugs. Evoked excitatory postsynaptic currents were done at a holding potential (Vh) of −80 mV in the presence of 30 μM bicuculline and 5 μM CGP 55845 (all from Tocris Bioscience, Ellisville, MO) 0.5 μM ω-Agatoxin IVA and 1 μM ω-Conotoxin GVIA (Tocris Bioscience, Ellisville, MO) were used to block P/Q and N-type Ca2+ channels, respectively. eIPSCs were evoked in granule cells in response to extracellular stimulation of the medial perforant path with a monopolar glass electrode (intensity: 50–150 μA, duration: 30 μs) filled with ACSF and connected with an isolated pulse stimulator (A-M Systems, Carlsborg, WA). The criteria used to define the extracellular stimulation were: (1) no failures in response to repeated 0.1 Hz stimulation; (2) postsynaptic responses at least threefold higher than the square root of noise; (3) latency and shape of synaptic current remained invariant. After finding a cell that met these criteria, we continued all the experiments at stimulation intensity 10% higher than the minimal needed, to avoid possible failures. See Supplementary Methods for additional details on the electrophysiology of primary neuronal cultures

Data analysis

All data were acquired with Clampex 10.2 and analysed offline with Clampfit 10.2 (pClamp, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) and MiniAnalysis (Synaptosoft, Decatur, GA). We inspected eIPSCs visually and considered only those that met the stimulation criteria (see above) and were not contaminated by spontaneous activity. Because of the high intrinsic variability of eIPSCs, 10–30 consecutive responses (at a stimulation frequency of 0.1 Hz) were averaged before the calculation of the peak amplitude and of the kinetic parameters. We considered the peak amplitude as the difference between baseline and the peak of the evoked response; charge as the area under the response; latency as the time from the stimulus artifact to the initiation of a postsynaptic response; rise time as the 10–90% time from the initiation of a response to the peak amplitude; The eIPSC and mIPSC deactivation response was fitted by double exponential equations of the form I(t)=Afast exp(−t/τfast)+Aslow exp(−t/τslow), where I(t) was the amplitude of IPSCs at time t, Afast and Aslow were the amplitudes of the fast and slow decay components, respectively, and τfast and τslow the corresponding decay time constants.

The size of the RRP of synchronous release (RRPsyn) and the probability that any given SV in the RRP will be released (Pves) were calculated using the cumulative amplitude analysis17,33. RRPsyn was determined by summing up the peak amplitudes of IPSC responses during a 2-s stimulation train at 40 Hz. The last 40 data points were fitted by linear regression and back-extrapolated to time 0. The intercept with the y axis yielded the RRPsyn, and the ratio between the first eIPSC amplitude and RRPsyn yielded the Pves. In the same way, we measured RRPtot by calculating the total area of the response induced by each stimulus of the train17,33, after subtracting the offset to the baseline.

We measured the delayed asynchronous release as the 1-s area of the postsynaptic current following a 40 Hz train, normalized to the 1-s area preceding the train (sIPSC area averaged from 5–10 s before the train). This measure of delayed asynchronous release considers both the offset of the last response of the stimulus train to the baseline, as well as the increase in the frequency of the spontaneous postsynaptic currents.

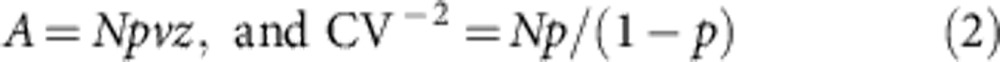

To analyse PPD, two brief stimulation pulses were applied at ISIs ranging between 10 and 4,000 ms (10–20 sweeps for each trial). Paired-pulse ratio (PPR) was calculated from the equation: PPR=100 × (I2−I1)/I1, where I1 and I2 are the mean amplitudes of the eIPSCs evoked by the conditioning and test stimuli, respectively17. Analysis of the pre/postsynaptic locus of PPD was performed as described by Malinow and Tsien32. We calculated:

|

where CV is the coefficient of variation, A is the peak amplitude of each response and σ is the variance of the peak amplitudes in a series of consecutive responses. From the binomial distribution of transmitter release:

|

because A2/σ2=(Npvz)2/Np (1−p) (vz)2=Np/(1−p), where p is the probability of release for each available quanta (N), v is the vesicular content and z is the postsynaptic response to a fixed amount of transmitter. On a linear plot (Fig. 2), the depression induced by the second stimulus (A2/A1) with respect to the ratio of coefficients of variation ((CV2/CV1)−2) should fall under the line if the cause of the depression is presynaptic according to equations (1) and (2)31,32.

Immunoprecipitation

Cortical neurons at 10–14 DIV were lysed in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, NP40 1%, SDS 0.1%) plus protease inhibitors (complete EDTA-free protease inhibitors, Roche Diagnostic, IN) for 1 h at 4 °C under constant agitation. After centrifugation at 16,000g for 30 min, protein concentration was quantified with Bradford Protein Assay (BioRad, Segrate, Italy). Protein lysates (1.5 mg per sample) were precleared using 25 μl protein G-Sepharose Fast Flow (GE Healthcare) for 1 h at 4 °C. Precleared lysates were incubated overnight at 4 °C with 5 μg of syn I or syn II antibodies, or anti-HA antibodies as control; immunocomplexes were then isolated by adding either protein G-Sepharose for synII, or anti-mouse IgG-coated Sepharose beads (no. 5946 Cell Signaling) for syn I, for 3 h at 4 °C. SDS–PAGE and western blotting were performed on precast 4–12% NuPAGE Novex Bis-Tris Gels (Life Technologies, Monza, Italy). After incubation with primary antibodies, membranes were incubated with fluorescently-conjugated secondary antibodies (ECL Plex goat α-rabbit IgG-Cy5, ECL Plex goat α-mouse IgG-Cy3) and revealed by a Typhoon TRIO+ Variable Mode Imager (both GE Healthcare, Milano). The following primary antibodies were used: monoclonal anti-Syn I (clone 10.2260), anti-Syn II (clone 19.2160) and anti-HA (no. 32-6700 Life Technologies), polyclonal antibodies anti-Cav2.1 (P/Q), anti-Cav2.2 (N) and anti-Cav2.3 (R) (no. C1353, C1478 and C1853, Sigma, Milano, Italy).

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean±s.e.m. with n=neurons/mice. For each group of data, an F-test for the comparison of the variances was used before the statistical testing. In case of non-homogeneity of variance, the statistical analysis was performed using the non-parametric Welch’s t-test for unequal variances. In the case of equal variances, we used the two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test. Paired t-tests were used according to the experimental design.

Author contributions

L.M., P.B. and F.B. design the study and planned the experiments. L.M. (patch-clamp), A.R. (electron microscopy) and F.C. (biochemistry) performed the experiments and analysed the data. G.L. analysed the electrophysiology data. L.M., P.B. and F.B. wrote the manuscript.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Medrihan, L. et al. Synapsin II desynchronizes neurotransmitter release at inhibitory synapses by interacting with presynaptic calcium channels. Nat. Commun. 4:1512 doi: 10.1038/ncomms2515 (2013).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures S1-S8, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary References

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs H.-T. Kao (Brown University, Providence, RI) and P. Greengard (The Rockefeller University, New York, NY) for providing us with the Syn II mutant mouse strain. We also thank Dr J. Scholz-Starke for help in the design of experiments and useful discussions. This study was supported by research grants from the Italian Ministry of University and Research (PRIN to F.B. and P.B.), the Italian Ministry of Health Progetto Giovani (to P.B.) and the Compagnia di San Paolo, Torino (to F.B. and P.B.). The support of Telethon-Italy (Grant GGP09134 to F.B. and GGP09066 to P.B.) is also acknowledged.

References

- Daw M. I., Tricoire L., Erdelyi F., Szabo G. & McBain C. J.. Asynchronous transmitter release from cholecystokinin-containing inhibitory interneurons is widespread and target-cell independent. J. Neurosci. 29, 11112–11122 (2009) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hefft S. & Jonas P.. Asynchronous GABA release generates long-lasting inhibition at a hippocampal interneuron-principal neuron synapse. Nat. Neurosci. 8, 1319–1328 (2005) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsu Y. et al. Competition between phasic and asynchronous release for recovered synaptic vesicles at developing hippocampal autaptic synapses. J. Neurosci. 24, 420–433 (2004) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagler D. J. Jr & Goda Y.. Properties of synchronous and asynchronous release during pulse train depression in cultured hippocampal neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 85, 2324–2334 (2001) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu T. & Trussell L. O.. Inhibitory transmission mediated by asynchronous transmitter release. Neuron 26, 683–694 (2000) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen K., Lambert J. D. & Jensen M. S.. Tetanus-induced asynchronous GABA release in cultured hippocampal neurons. Brain Res. 880, 198–201 (2000) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atluri P. P. & Regehr W. G.. Delayed release of neurotransmitter from cerebellar granule cells. J. Neurosci. 18, 8214–8227 (1998) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goda Y. & Stevens C. F.. Two components of transmitter release at a central synapse. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 91, 12942–12946 (1994) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geppert M. et al. Synaptotagmin I: a major Ca2+ sensor for transmitter release at a central synapse. Cell 79, 717–727 (1994) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maximov A. & Sudhof T. C.. Autonomous function of synaptotagmin 1 in triggering synchronous release independent of asynchronous release. Neuron 48, 547–554 (2005) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiki T. & Augustine G. J.. Synaptotagmin I synchronizes transmitter release in mouse hippocampal neurons. J. Neurosci. 24, 6127–6132 (2004) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J. et al. A dual-Ca2+-sensor model for neurotransmitter release in a central synapse. Nature 450, 676–682 (2007) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter A. M., Groffen A. J., Sorensen J. B. & Verhage M.. Multiple Ca2+ sensors in secretion: teammates, competitors or autocrats? Trends Neurosci. 34, 487–497 (2011) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raingo J. et al. VAMP4 directs synaptic vesicles to a pool that selectively maintains asynchronous neurotransmission. Nat. Neurosci. 15, 738–745 (2012) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesca F., Baldelli P., Valtorta F. & Benfenati F.. The synapsins: key actors of synapse function and plasticity. Prog. Neurobiol. 91, 313–348 (2010) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitler D. et al. Different presynaptic roles of synapsins at excitatory and inhibitory synapses. J. Neurosci. 24, 11368–11380 (2004) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldelli P., Fassio A., Valtorta F. & Benfenati F.. Lack of synapsin I reduces the readily releasable pool of synaptic vesicles at central inhibitory synapses. J. Neurosci. 27, 13520–13531 (2007) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fassio A., Raimondi A., Lignani G., Benfenati F. & Baldelli P.. Synapsins: From synapse to network hyperexcitability and epilepsy. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 22, 408–415 (2011) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalleri G. L. et al. Multicentre search for genetic susceptibility loci in sporadic epilepsy syndrome and seizure types: a case-control study. Lancet Neurol. 6, 970–980 (2007) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakhan R., Kalita J., Misra U. K., Kumari R. & Mittal B.. Association of intronic polymorphism rs3773364 A>G in synapsin-2 gene with idiopathic epilepsy. Synapse 64, 403–408 (2010) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fassio A. et al. SYN1 loss-of-function mutations in autism and partial epilepsy cause impaired synaptic function. Hum. Mol. Genet. 20, 2297–2307 (2011) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia C. C. et al. Identification of a mutation in synapsin I, a synaptic vesicle protein, in a family with epilepsy. J. Med. Genet. 41, 183–186 (2004) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman W. L. et al. Synapsin II and calcium regulate vesicle docking and the cross-talk between vesicle pools at the mouse motor terminals. J. Physiol. 586, 4649–4673 (2008) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitler D., Cheng Q., Greengard P. & Augustine G. J.. Synapsin IIa controls the reserve pool of glutamatergic synaptic vesicles. J. Neurosci. 28, 10835–10843 (2008) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosahl T. W. et al. Essential functions of synapsins I and II in synaptic vesicle regulation. Nature 375, 488–493 (1995) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. B., Ye G. L., Liu X. S., Pasternak J. F. & Trommer B. L.. GABAA currents in immature dentate gyrus granule cells. J. Neurophysiol. 80, 2255–2267 (1998) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrant M. & Nusser Z.. Variations on an inhibitory theme: phasic and tonic activation of GABA(A) receptors. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 6, 215–229 (2005) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacson J. S. & Walmsley B.. Counting quanta: direct measurements of transmitter release at a central synapse. Neuron 15, 875–884 (1995) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirischuk S., Clements J. D. & Grantyn R.. Presynaptic and postsynaptic mechanisms underlie paired pulse depression at single GABAergic boutons in rat collicular cultures. J. Physiol. 543, 99–116 (2002) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker R. S. & Regehr W. G.. Short-term synaptic plasticity. Annu Rev. Physiol. 64, 355–405 (2002) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraushaar U. & Jonas P.. Efficacy and stability of quantal GABA release at a hippocampal interneuron-principal neuron synapse. J. Neurosci. 20, 5594–5607 (2000) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malinow R. & Tsien R. W.. Presynaptic enhancement shown by whole-cell recordings of long-term potentiation in hippocampal slices. Nature 346, 177–180 (1990) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens C. F. & Williams J. H.. Discharge of the readily releasable pool with action potentials at hippocampal synapses. J. Neurophysiol. 98, 3221–3229 (2007) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schikorski T. & Stevens C. F.. Morphological correlates of functionally defined synaptic vesicle populations. Nat. Neurosci. 4, 391–395 (2001) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsu Y. & Murphy T. H.. Optical postsynaptic measurement of vesicle release rates for hippocampal synapses undergoing asynchronous release during train stimulation. J. Neurosci. 24, 9076–9086 (2004) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manseau F. et al. Desynchronization of neocortical networks by asynchronous release of GABA at autaptic and synaptic contacts from fast-spiking interneurons. PLoS Biol. 8, e1000492 (2010) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu-Friedman M. A. & Regehr W. G.. Presynaptic strontium dynamics and synaptic transmission. Biophys. J. 76, 2029–2042 (1999) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu-Friedman M. A. & Regehr W. G.. Probing fundamental aspects of synaptic transmission with strontium. J. Neurosci. 20, 4414–4422 (2000) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumpel E. & Behrends J. C.. Sr2+-dependent asynchronous evoked transmission at rat striatal inhibitory synapses in vitro. J. Physiol. 514, (Pt 2): 447–458 (1999) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosaka M. & Sudhof T. C.. Synapsins I and II are ATP-binding proteins with differential Ca2+ regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 1425–1429 (1998) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller C. S. et al. Quantitative proteomics of the Cav2 channel nano-environments in the mammalian brain. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 14950–14957 (2010) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farisello P. et al. Synaptic and extrasynaptic origin of the excitation/inhibition imbalance in the Hippocampus of Synapsin I/II/III Knockout Mice. Cereb. Cortex (doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhs041) (2012) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corradi A. et al. Synapsin-I- and synapsin-II-null mice display an increased age-dependent cognitive impairment. J. Cell Sci. 121, 3042–3051 (2008) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fassio A. et al. The synapsin domain E accelerates the exoendocytotic cycle of synaptic vesicles in cerebellar Purkinje cells. J. Cell Sci. 119, 4257–4268 (2006) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilfiker S. et al. Two sites of action for synapsin domain E in regulating neurotransmitter release. Nat. Neurosci. 1, 29–35 (1998) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen H. et al. Distinct roles for two synaptotagmin isoforms in synchronous and asynchronous transmitter release at zebrafish neuromuscular junction. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 13906–13911 (2010) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maximov A. et al. Genetic analysis of synaptotagmin-7 function in synaptic vesicle exocytosis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 3986–3991 (2008) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao J., Gaffaney J. D., Kwon S. E. & Chapman E. R.. Doc2 is a Ca2+ sensor required for asynchronous neurotransmitter release. Cell 147, 666–677 (2011) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Few A. P. et al. Asynchronous Ca2+ current conducted by voltage-gated Ca2+ (CaV)-2.1 and CaV2.2 channels and its implications for asynchronous neurotransmitter release. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, E452–E460 (2012) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggermann E., Bucurenciu I., Goswami S. P. & Jonas P.. Nanodomain coupling between Ca(2) channels and sensors of exocytosis at fast mammalian synapses. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 13, 7–21 (2012) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman W. L. & Bykhovskaia M.. Cooperative regulation of neurotransmitter release by Rab3a and synapsin II. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 44, 190–200 (2010) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovedi S., Darchen F., Valtorta F., Greengard P. & Benfenati F.. Synapsin is a novel Rab3 effector protein on small synaptic vesicles. II. Functional effects of the Rab3A-synapsin I interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 43769–43779 (2004) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaeser P. S. et al. RIM proteins tether Ca2+ channels to presynaptic active zones via a direct PDZ-domain interaction. Cell 144, 282–295 (2011) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiappalone M. et al. Opposite changes in glutamatergic and GABAergic transmission underlie the diffuse hyperexcitability of synapsin I-deficient cortical networks. Cereb. Cortex 19, 1422–1439 (2009) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholz-Starke J., Cesca F., Schiavo G., Benfenati F. & Baldelli P.. Kidins220/ARMS is a novel modulator of short-term synaptic plasticity in hippocampal GABAergic neurons. PLoS ONE 7, e35785 (2012) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etholm L., Bahonjic E., Walaas S. I., Kao H. T. & Heggelund P.. Neuroethologically delineated differences in the seizure behavior of Synapsin 1 and Synapsin 2 knock-out mice. Epilepsy Res. 99, 252–259 (2012) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang M. et al. Enhancement of asynchronous release from fast-spiking interneuron in human and rat epileptic neocortex. PLoS Biol. 10, e1001324 (2012) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishnan V., Kuo S. P., Roberts P. D. & Trussell L. O.. Slow glycinergic transmission mediated by transmitter pooling. Nat. Neurosci. 12, 286–294 (2009) . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capogna M. & Pearce R. A.. GABA A,slow: causes and consequences. Trends Neurosci. 34, 101–112 (2011) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaccaro P. et al. Anti-synapsin monoclonal antibodies: epitope mapping and inhibitory effects on phosphorylation and Grb2 binding. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 52, 1–16 (1997) . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures S1-S8, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary References