Abstract

Background

Black women experience higher rates of cardiovascular disease (CVD) than white women, though evidence for racial differences in subclinical CVD is mixed. Few studies have examined multiple roles (number, perceived stress, and/or reward) in relation to subclinical CVD, or whether those effects differ by race.

Purpose

To investigate the effects of multiple roles on 2-year progression of coronary artery calcification (CAC).

Methods

Subjects were 104 black and 232 white women (mean age 50.8 years). Stress and reward from four roles (spouse, parent, employee, caregiver) were assessed on 5-point scales. CAC progression was defined as an increase of ≥10 Agatston units.

Results

White women reported higher rewards from their multiple roles than black women, yet black women showed cardiovascular benefits from role rewards. Among black women only, higher role rewards were related significantly to lower CAC progression, adjusting for BMI, blood pressure, and other known CVD risk factors. Blacks reported fewer roles but similar role stress as whites; role number and stress were unrelated to CAC progression.

Conclusion

Rewarding roles may be a novel protective psychosocial factor for progression of coronary calcium among black women.

Keywords: multiple roles, role stress, role reward, women, middle-aged, coronary artery calcium

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death for women in the United States (1). Black women experience rates of CVD that are almost 60% higher than those observed in white women (1,2). It is likely that multiple lifestyle, environmental, and biologic factors contribute to this disparity, yet despite much research (2), determinants contributing to this excess risk among black women remain poorly understood. Racial/ethnic disparities in utilization of, or access to, health care are well-documented (3,4); however, these and other socioeconomic and clinical risk factors cannot account for the observed differences in CVD morbidity and mortality (5). Over the past two decades, greater attention has been paid to subclinical precursors of CVD. This is because such measures as coronary artery calcification (CAC), a marker of plaque burden, can be measured well before the onset of clinical symptoms. The literature on racial/ethnic differences in CAC is mixed, with some studies showing less CAC in blacks than whites, and others showing no difference (6). Additional research is warranted to examine novel factors that may influence subclinical CVD in black and white women and to better understand racial disparities in CVD risk.

Negative emotional states (e.g., depression, hopelessness, anxiety, anger and hostility), low social support, and psychological stress are related to CVD morbidity and mortality in women (7–12), but few studies have examined whether these psychosocial risk factors vary in effect by race. In an analysis based on black and white women enrolled in the Women’s Health Initiative, more pessimistic and cynically hostile attitudes were related to all cause mortality, with the effects significantly stronger in black women than in white women (13). However, optimism was protective against coronary heart disease incidence and mortality only among white women.

The literature examining psychosocial factors and precursors of CVD suggests that effects may vary by race. A series of papers from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) demonstrate this point. One report on the effects of chronic stress burden on carotid artery intima-media thickness (IMT) found higher levels of chronic stress and higher levels of IMT in black than white women and showed that stress was related to IMT levels only in blacks (14). Depressive symptoms were related cross-sectionally to aortic calcification only in blacks (15) and exposure to discrimination and unfair treatment was related cross-sectionally to CAC also only in black women (16). However, a report from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) found no consistent race/ethnic differences in the associations between psychosocial functioning and CAC in older women or men (17). In contrast, we have shown recently that depression is significantly related to CAC progression in both black and white women (18,19)

A recent review of psychosocial factors in women’s CVD suggested that work stress may be less important, and home stress, including the stress of multiple roles, may be more important, in women than men, and particularly in black women (20). Furthermore, the review suggested that positive psychosocial factors might be protective for women’s CVD. Research has shown that involvement in multiple roles enhances women’s sense of well being (21,22) due to the potential social and psychological benefits of occupying different roles simultaneously (23). However, perceptions of stress and rewards from occupying specific roles have rarely been measured. Moreover, there has been very little research on multiple role stress and CVD or whether role perceptions vary by race and/or relate to CVD risk differently in blacks or whites. Early results from the Framingham study suggested that conflicting roles may contribute to the development of CVD among women (24), but this study was limited to whites. In a study of Swedish women, those reporting marital stress were more likely to have a recurrent cardiac event than women with work stress, and women with both stressors had the worst prognosis (25). Higher prevalence and accelerated progression of atherosclerosis were observed among women reporting marital dissatisfaction (26), although this latter study had too few minority women to look at differences by race.

Having multiple social roles may be beneficial by providing a large diverse social network and social support, which has been shown to positively affect cardiovascular events (27) as well as atherosclerosis (28), including lower levels of CAC (29). Stressors have been linked to heightened neurohormonal levels such as epinephrine and cortisol, showing a possible biopsychosocial mechanism (28). Cardiovascular recovery rates from acute stressors have been shown to be faster in black than in white women (30) and in women with a positive emotional style (31).

The primary goal of the current study was to examine the associations between multiple roles and progression of CAC in a sample of middle-aged black and white women from two sites of SWAN. We hypothesized that higher stress is related to more progression, that larger numbers of roles and higher rewards from multiple roles is related to less progression of CAC, and that these effects are independent of known psychosocial risk factors such as social support and depressive symptoms. Because black and white women engage in different patterns of roles, and because black women are at much higher risk for CVD, we examined the relationship of CAC progression to multiple roles variables separately in the two racial groups. We were particularly interested in the question of whether stress and rewards from multiple roles was related to CAC levels in black women.

Methods

Study Population and Procedures

SWAN is a seven-site, multi-ethnic longitudinal study of women transitioning through menopause with ongoing annual interviews. Women were eligible for the SWAN baseline examination in 1996 who were 42–52 years of age, not pregnant or breastfeeding, had an intact uterus and at least 1 ovary, had menstruated within the past 3 months, and were from one of the five pre-specified racial/ethnic groups (non-Hispanic white, black, Chinese/Chinese-American, Japanese/Japanese-American, Hispanic) (32). SWAN Heart was designed as an ancillary SWAN study to examine subclinical CVD among healthy women; details of the study have been published (16). SWAN Heart was conducted at the Chicago and Pittsburgh sites only, and recruited women without a history of CVD (n=608) between 2001 and 2003. These sites recruited only non-Hispanic white and black women. Coronary calcium (CAC) measurements were obtained on 561 women at SWAN Heart baseline and on 362 of these women at follow-up an average of 2.3 years later. Only women with both baseline and follow-up CAC scans were eligible for the current analyses. We excluded 13 women with diabetes (glucose of at least 126mg/dL or on insulin) as well as 13 women with missing information on role occupation, leaving 336 for analysis. Compared to women excluded from the analysis because of missing follow-up CAC measures, women in the analytic sample were less likely to be black, had lower systolic blood pressure, and lower glucose levels. The women in the analytic sample had fewer roles, but did not differ in baseline calcium scores, average reported rewards or stresses across the occupied roles and other relevant attributes presented in Table 1. All women provided written informed consent for each SWAN visit, including both SWAN Heart visits. The research protocol was approved by each site’s Institutional Review Board.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Cohort Overall and by Race at Baseline

| Range | White | Black | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 232 | 104 | |

| Study Site | |||

| Chicago, N (%) | 117 (50.4) | 67 (64.4)** | |

| Pittsburgh, N (%) | 115 (49.6) | 37 (35.6) | |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 48–58 | 50.9 (2.7) | 50.6 (2.7) |

| Time between scans, years, mean (SD) | 0.9–4.3 | 2.3 (0.5) | 2.3 (0.4) |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 18.5–50.7 | 27.9 (5.7) | 31.3 (6.9)**** |

| SBP, mmHg, mean (SD) | 86–183 | 114.4 (13.3) | 124.3 (16.1)**** |

| DBP, mmHg, mean (SD) | 50–110 | 73.6 (9.2) | 78.9 (9.2)**** |

| BP medication use, N (%) | 1=present | 25 (10.8) | 23 (22.1)*** |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL, mean (SD) | 39–589 | 118.1 (64.7) | 104.2 (58.0)* |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL, mean (SD) | 24–122 | 58.5 (14.4) | 56.6 (12.5) |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL, mean (SD) | 48–244 | 117.3 (31.4) | 119.4 (35.5) |

| Statin a use, N (%) | 1=present | 12 (5.2) | 5 (4.8) |

| Current Smoker, N (%) | 1=present | 33 (14.2) | 16 (15.4) |

| Education | ** | ||

| ≤ High School, N (%) | 35 (15.1) | 20 (19.2) | |

| Some College, N (%) | 63 (27.2) | 39 (37.5) | |

| ≥ College, N (%) | 134 (57.7) | 45 (43.3) | |

| Menopausal Status | |||

| Hormone Therapy use, N (%) | 1=present | 31 (13.4) | 8 (7.7) |

| Pre-/Early Peri-menopausal, N (%) | 1=present | 136 (58.6) | 59 (56.7) |

| Low Social Support, N (%) | 1=present | 35 (15.1) | 34 (32.7)**** |

| Depressive Symptoms ≥ 16, N (%) | 1=present | 31 (13.4) | 7 (6.8)* |

| Calcium Score at baseline, mean (SD) | 0–311.5 | 12.9 (44.7) | 8.4 (15.4) |

| CAC at baseline, N (%) | |||

| 0 | 142 (61.2) | 47 (45.2)*** | |

| >0,<10 | 53 (22.8) | 27 (26.0) | |

| ≥10,<100 | 30 (12.9) | 29 (27.9) | |

| 100+ | 7 (3.0) | 1 (1.0) | |

| CAC Progression b, N (%) | 1=present | 42 (18.1) | 19 (18.3) |

| Employed, N (%) | 1=present | 201 (87.0) | 91 (88.4) |

| Relationship, N (%) | 1=present | 208 (89.6) | 73 (70.2)**** |

| Mother, N (%) | 1=present | 200 (86.6) | 92 (88.5) |

| Caregiver, N (%) | 1=present | 35 (15.2) | 13 (12.6) |

| Number of roles occupied, mean (SD) | 1–4 | 2.8 (0.7) | 2.6 (0.7)* |

cholesterol lowering medication

Δ CAC ≥ 10 Agatston units

p<0.001,

p<0.01,

p<0.05,

<0.10

Continuous variables were compared with unequal variances t-tests, proportions were compared with chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact tests in case of small cell sizes.

Coronary Artery Calcium

CAC was assessed by electron beam computed tomography (EBCT) in 2 passes. The first pass provided landmarks and the second provided coronary artery images. Between 30 and 40 contiguous 3-mm-thick transverse images from the level of the aortic root to the apex of the heart were obtained during maximal breath holding with ECG triggering to obtain a 100-millisecond exposure during the same phase of the cardiac cycle (60% of the RR interval). Scans were scored at the University of Pittsburgh with a DICOM workstation and software by AcuImage, Inc (South San Francisco, CA) using established methods (33). Calcification was considered present if at least 3 contiguous pixels showed >130 Hounsfield units. The calcium score was the sum of scores for each of the 4 major epicardial coronary arteries (34). The reproducibility of the scoring system has been previously demonstrated at the University of Pittsburgh, with an intraclass correlation of 0.99 (35).

Study Variables

All participants completed baseline and annual exams in SWAN. These exams included questionnaires, anthropometry, and a blood draw in order to assess sociodemographic and CVD risk factors. Data on multiple roles and covariates were obtained at the annual SWAN examination closest in time to each participant’s first EBCT scan (i.e., the SWAN Heart study baseline visit). These scans were performed within 8 months of the annual SWAN visit, and 95% were done within 4 months.

Multiple Roles

The occupancy of specific roles was determined by a short questionnaire based on the Multiple Role Questionnaire (36). For each role occupied, the participants answered yes or no to indicate tenure in one or more of the following social roles: employed for pay, married or in a committed relationship, having children or stepchildren, and caregiving for an older or disabled family member. Participants rated the reward and stress from each role separately on a five-point scale, ranging from 1 (not at all rewarding (stressful)) to 5 (extremely rewarding (stressful)). For each participant, the average reward and average stress scores were computed by summing the rated rewards (stresses) from each role and dividing by the total number of roles occupied.

Covariates

Covariates were chosen from the literature based on their association with CAC. Age, highest educational degree, smoking status, hormone therapy (HT), and menopausal status were self-reported. Menopausal Status was assessed by bleeding criteria as pre-menopausal (normal cycling), early peri-menopausal (irregular cycles with bleeding in the past 3 months), late peri-menopausal (irregular cycles with bleeding in the past 11 months but not within the last 3 months), post-menopausal (no menses for 12 months or more).

Resting blood pressure was measured with a mercury sphygmomanometer, using an appropriately sized cuff and a standard protocol with participants seated and at least a 5-minute rest. Two blood pressure readings were obtained, two minutes apart, and averaged. Only systolic blood pressure (SBP) was used as a covariate. Standardized protocols were used to measure height and weight. Height was measured without shoes using a stadiometer. Weight was measured without shoes and with light indoor clothing using scales calibrated to a standard on a monthly basis. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) was measured by sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and calculated using the Friedewald equation (37).

Depressive symptoms were assessed by the 20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies

Depression Scale (CES-D) (38), validated with good test-retest reliability in racially diverse samples (39), and used extensively in epidemiological studies. A standard cutoff (≥16) was used to represent clinically significant depressive symptomatology (40). Social support was measured with 4 items from the Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey (41). Because there are no established cut points for the Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Scale, we used the bottom quintile to quantify low social support.

Data Analysis

Participant characteristics were summarized as mean (standard deviation (SD)) and N (%) for the cohort overall and compared by race with unequal variances t-tests or chi-square tests. A few participants were missing one or more covariates at the SWAN Heart baseline visit. Single variables were missing on at most 8 women (2.3%) except for lipids which were missing on 16 (4.6%) women. Missing covariate data were imputed either by using values obtained at the previous SWAN visit (e.g. smoking), or by using person-specific linear regression on all measures obtained up to SWAN Heart baseline (BMI, blood pressure, LDL-C).

Almost all (98%) of the CAC scores at baseline were below 10 Agatston units. For initial CAC in this range, an increase by 10 units is considered clinically significant (42). Moreover, this cutoff has been used previously in studies of asymptomatic subjects to identify significant CAC progression (43) as well as in two reports from SWAN Heart (18,19). Therefore, we defined progression of CAC as a change in Agatston score of 10 or greater. Sensitivity analyses revealed that using alternative cut points (such as 5 or 15 Agatston units) did not alter the risk factor relationships (data not shown). Due to its interpretability, we selected the relative risk (RR) (44) as the summary of the association between CAC progression and the participants’ attributes. Because calcium change ≥10 units was not a rare event, with approximately 18% of the cohort exhibiting such progression, logistic regression could potentially overestimate the relative risk. Consequently, the RR estimates, adjusted for covariates, were directly obtained via the maximum likelihood (MLE) parameter estimates of the log-binomial regression model using SAS PROC GENMOD (SAS version 9.1, SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC). When a convergence issue arose with the standard estimation algorithm, the problem was circumvented through the utilization of a novel computational method to estimate the MLE of the log-binomial model proposed (45).

Rewards and stresses resulting from the four roles as well as covariates were assessed at the time of the first CAC measurement. Separate RR regression models were fit for the number of roles, average role reward, and average role stress. In a set of base models, we adjusted for age, time between scans, menopausal status, hormone therapy, and education. A second set of models was created by adding other covariates known from the literature to influence CAC progression, namely SBP, BMI, LDL-C, smoking status, and presence of CAC at baseline. Estimates for the multiple roles did not differ in the base and the final models, and we therefore only present the final models. The final models contained many statistically non-significant terms. Therefore, a backward elimination procedure using a liberal p-value of 0.20 for removing covariates was employed to reduce the number of covariates and the variance. To assess whether the reward from multiple roles was independent of known psychosocial risk factors previously related to CAC, social support and depressive symptoms were added to the final as well as to the reduced model.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the cohort, including role occupancy, by race. Black women did not differ significantly from white women in age, menopausal status, HT use, smoking status, HDL cholesterol, and LDL cholesterol. Black women had significantly greater BMI and higher blood pressure. Although black women had a higher percentage of positive baseline calcium scores (54.8% versus 38.8%, p=0.006), there was no difference by race in the percentage of women showing an increase of 10 Agatston units or more; approximately 18% of black and white women showed this kind of progression.

More than 86% of both black and white women were employed, or had children; approximately 13% of blacks and 15% of whites were caregivers to an older or disabled family member. Women who had only one role (10 whites and 8 blacks) or 4 roles (20 whites and 7 blacks) were uncommon. Blacks were less likely to be married or in a committed relationship (70% vs. 90%, p<0.001). As a result, black women had fewer roles than white women did.

Perceived Reward and Stress

Table 2 shows reported levels of stress and rewards from the multiple roles for black and white women. Perceived role rewards from motherhood and caregiving were rated similarly by black and white women. In contrast, rewards from relationships (p<0.001), employment (p=0.049), and overall (p=0.005) were rated lower by black than white women. Perceived role stress ratings were similar for black and white women with one exception. Black women indicated more stress from relationships than white women (p=0.03). There was no difference in average stress across occupied roles between the racial groups.

Table 2.

Cohort Role Characteristics by Race

| Range | White | Black | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| N | 232 | 104 | |

| Stress | |||

| Employment, mean (SD) | 1–5 | 3.1 (1.1) | 3.1 (1.2) |

| Relationship, mean (SD) | 1–5 | 2.3 (1.0) | 2.6 (1.1)** |

| Motherhood, mean (SD) | 1–5 | 2.7 (1.0) | 2.5 (1.1) |

| Caregiver, mean (SD) | 1–5 | 3.1 (0.9) | 3.1 (1.1) |

| Average Role Stress, mean (SD) | 1–5 | 2.7 (0.8) | 2.8 (0.8) |

| Reward | |||

| Employment, mean (SD) | 1–5 | 3.7 (0.9) | 3.5 (0.8)** |

| Relationship, mean (SD) | 1–5 | 3.9 (1.0) | 3.4 (1.2)**** |

| Motherhood, mean (SD) | 1–5 | 4.4 (0.8) | 4.3 (0.9) |

| Caregiver, mean (SD) | 1–5 | 3.1 (1.1) | 2.9 (1.1) |

| Average Role Reward, mean (SD) | 1–5 | 4.0 (0.7) | 3.7 (0.7)** |

p<0.001,

p<0.05

Variables were compared with unequal variances t-tests.

For both black and white women, ratings of stress differed in magnitude across roles. Specifically, stress due to employment and caregiving was rated highest. Job stress was significantly higher than stress from motherhood (p<0.001 for black women, p=0.023 for white women) and stress from relationships (p=0.034 for black women, p<0.001 for white women). Stress from caregiving was significantly higher than relationship stress in white women only (p<0.001). Motherhood was considered the most rewarding role in both racial groups, and rewards from this role were significantly higher than rewards from any other role (all p<0.005). Rewards from caregiving were lower than rewards from relationship (p<0.001 for white women, p=0.038 for black women) and lower than rewards from employment in white women only (p=0.032).

Progression of CAC

Women with a positive calcium score at baseline were more likely to show CAC progression than others did. This was true for white women 35/90=39% vs. 7/142=5%, p<0.001) and black women: 16/57=28% vs. 3/47=6% (p=0.004). Table 3 shows the baseline characteristics of the cohort by CAC progression separately for black and white women. CAC progression was positively associated with age, BMI, blood pressure, triglycerides, and LDL-C, and negatively with rewards from multiple roles. These associations were stronger in white than in black women, but the magnitude of the differences between those with and without CAC progression was similar in the two racial groups.

Table 3.

Characteristics of Black and White Women at Baseline by CAC Progression

| White

|

Black

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Δ CAC <10 | Δ CAC ≥ 10 | Δ CAC <10 | Δ CAC ≥ 10 | |

| N | 190 | 42 | 85 | 19 |

| Study Site | ||||

| Chicago, N (%) | 98 (51.6) | 19 (45.2) | 51 (60.0) | 16 (84.2)** |

| Pittsburgh, N (%) | 92 (48.4) | 23 (54.8) | 34 (40.0) | 3 (15.8) |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 50.6 (2.7) | 51.9 (2.9)** | 50.4 (2.5) | 51.4 (3.4) |

| Time between scans, yrs, mean (SD) | 2.3 (0.4) | 2.3 (0.5) | 2.3 (0.4) | 2.3 (0.6) |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 27 (5.1) | 32 (6.6)**** | 30.3 (6.5) | 35.5 (7.3)*** |

| SBP, mmHg, mean (SD) | 112.5 (11.8) | 122.5 (16.4)**** | 123.2 (16.5) | 129.1 (13.4) |

| DBP, mmHg, mean (SD) | 72.4 (8.5) | 78.9 (10.4)**** | 78.1 (9.0) | 82.5 (9.6)* |

| BP medication use, N (%) | 21 (11.1) | 4 (9.5) | 15 (17.7) | 8 (42.1) |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL, mean (SD) | 113.5 (56.1) | 138.5 (92.6)* | 100.4 (53.8) | 120.7 (73.1) |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL, mean (SD) | 58.7 (14.0) | 57.3 (16.5) | 57.4 (12.7) | 52.7 (11.1) |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL, mean (SD) | 115.5 (31.0) | 125.8 (32)* | 119.7 (36.1) | 122.4 (28) |

| Statin a use, N (%) | 8 (4.2) | 4 (9.5) | 3 (3.5) | 2 (10.5) |

| Current Smoker, N (%) | 27 (14.2) | 6 (14.3) | 14 (16.5) | 2 (10.5) |

| Education | * | |||

| ≤ High School, N (%) | 24 (12.6) | 11 (26.2) | 17 (20.0) | 3 (15.8) |

| Some College, N (%) | 54 (28.4) | 9 (21.4) | 29 (34.1) | 10 (52.6) |

| ≥ College, N (%) | 112 (58.9) | 22 (52.4) | 39 (45.9) | 6 (31.6) |

| Menopausal Status | ||||

| Hormone Therapy use, N (%) | 28 (14.7) | 3 (7.1) | 7 (8.2) | 1 (5.3) |

| Pre-/Early Peri-menopausal, N (%) | 113 (59.5) | 23 (54.8) | 51 (60.0) | 8 (42.1) |

| Low Social Support, N (%) | 26 (13.8) | 8 (19.0) | 25 (29.8) | 8 (42.1) |

| Depressive Symptoms ≥ 16, N (%) | 21 (11.1) | 10 (23.8) | 6 (7.1) | 1 (5.3) |

| Baseline Calcium Score, mean (SD) | ||||

| CAC at baseline, N (%) | ||||

| 0 | 135 (71.1) | 7 (16.7)*** | 44 (51.8) | 3 (15.8)*** |

| >0,<10 | 41 (21.6) | 12 (28.6) | 24 (28.2) | 3 (15.8) |

| ≥10,<100 | 14 (7.4) | 16 (38.1) | 17 (20.0) | 12 (63.2) |

| 100+ | 0 (0) | 7 (16.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (5.3) |

| Number of roles occupied, mean (SD) | 2.8 (0.7) | 2.8 (0.6) | 2.6 (0.7) | 2.4 (1.0) |

| Average Role Stress, mean (SD) | 2.8 (0.8) | 2.6 (0.8) | 2.7 (0.8) | 3.0 (0.8) |

| Average Role Reward, mean (SD) | 4.0 (0.7) | 3.8 (0.6)* | 3.8 (0.7) | 3.5 (0.7) |

cholesterol lowering medication

p<0.001,

p<0.01,

p<0.05,

p<0.10

Continuous variables were compared with unequal variances t-tests, proportions were compared with chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact tests in case of small cell sizes.

Multiple Roles and Progression of CAC

Table 4 shows results of the relative risk regression models, relating the (a) number of roles, (b) stresses, and (c) rewards from multiple roles to CAC progression in unadjusted as well as in multivariable adjusted analyses. Point estimates for the adjusted analyses were similar to the unadjusted analyses. For white women, none of the multiple roles variables was significantly related to CAC progression, although all role measures showed a similar protective trend. The more roles, the greater the perceived reward, and even the more stress reported, the less likely white women experienced CAC progression. Significant covariates for CAC progression in whites were presence of CAC at baseline and SBP. Presence of baseline CAC increased the risk of CAC progression more than six-fold in white women.

Table 4.

Multivariate Model Relating Multiple Roles to CAC Progression for White and Black Women

| White Women RR (95% CI) |

Black Women RR (95% CI) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| a) N of Roles | Unadjusted | N of Roles | 0.97 (0.65–1.45) | 0.69 (0.38–1.24) |

|

| ||||

| Adjusted | BMI | 1.01 (0.98–1.04) | 1.05 (0.99–1.12) | |

| SBP | 1.02 (1.00–1.03)** | 0.99 (0.97–1.02) | ||

| CAC at Baseline | 6.26 (2.79–14.05)**** | 2.14 (0.57–8.06) | ||

| N of Roles | 0.79 (0.48–1.30) | 0.66 (0.39–1.11) | ||

|

| ||||

| b) Role Stress | Unadjusted | Role Stress | 0.78 (0.54–1.12) | 1.35 (0.75–2.43) |

|

| ||||

| Adjusted | BMI | 1.00 (0.95–1.05) | 1.04 (0.98–1.11) | |

| SBP | 1.02 (1.00–1.04)** | 1.00 (0.98–1.02) | ||

| CAC at Baseline | 6.31 (2.70–14.79)**** | 2.40 (0.65–8.83) | ||

| Average Role Stress | 0.79 (0.56–1.12) | 1.35 (0.79–2.31) | ||

|

| ||||

| c) Role Reward | Unadjusted | Role Reward | 0.78 (0.55–1.10) | 0.61 (0.33–1.12) |

|

| ||||

| Adjusted | BMI | 1.00 (0.97–1.03) | 1.05 (1.00–1.11)** | |

| SBP | 1.02 (1.00–1.03)** | 1.00 (0.98–1.01) | ||

| CAC at Baseline | 6.30 (2.75–14.42)**** | 2.37 (0.65–8.69) | ||

| Average Role Reward | 0.81 (0.53–1.24) | 0.49 (0.29–0.83)*** | ||

p<0.001,

p<0.01,

p<0.05

Adjusted for time between scans, age, education, menopausal status, HT use, LDL–C, and smoking (all p>0.10 in all models).

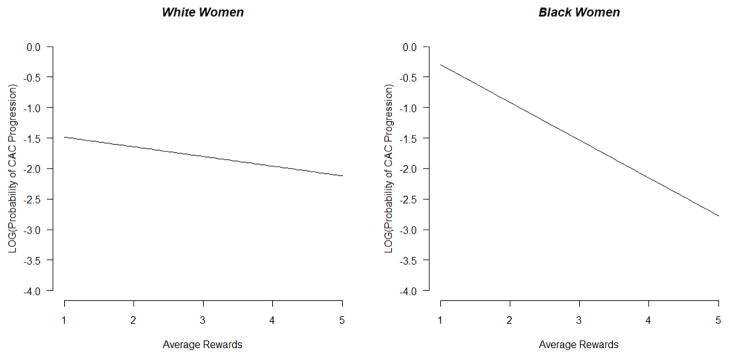

For black women, the relative risk regression models showed a significant benefit of rewarding roles. An increase by 1 unit in average rewards reduced the risk of CAC progression by 50%. Figure 1 presents the impact of rewarding roles for white and black women. In contrast to the findings for role rewards, the number of roles and average stress from those roles were unrelated to CAC progression for black women, although it should be noted that the relationship of these role measures to CAC were in different directions, with number of roles trending in the protective direction. The presence of CAC at baseline was not significantly related to CAC progression in black women. The other covariates also were unrelated to CAC progression in blacks, with one exception. In the model with average rewards, BMI was significantly positively related to CAC progression. Only 19 out of 104 black women showed CAC progression, and the model included a large number of covariates; therefore, the estimate for role rewards has to be taken with caution. In sensitivity analyses, we eliminated non-significant covariates one at a time, but the estimate for rewards in the black women did not change. Contrasting the results from Table 3 and Table 4, we found a benefit of rewards from multiple roles for white women before adjusting for CV risk factors, but after adjusting (for BMI in particular), this effect was not significant. For black women, the effect of rewarding social roles became stronger after covariate adjustment.

Figure 1.

Effect of average rewards from multiple roles on CAC progression in white and black women. Models were adjusted for time between scans, age, education, menopausal status, use of hormone therapy, low density lipoprotein cholesterol, smoking, body mass index, systolic blood pressure, and baseline CAC, with all covariates held at their mean in analyses. CAC coronary artery calcium.

Graphed values are from relative risk regression models, in which the natural logarithm of the probability of CAC progression occurring is modeled as a linear function of the covariates.

We conducted secondary analyses to assess whether the effect of rewarding roles was independent of known psychosocial predictors. Including social support or depressive symptoms in the models for average rewards in black women did not alter the findings.

Discussion

Most studies of multiple roles have not included assessments of rewarding aspects of these roles. In our analysis, we found that rewarding roles may be beneficial for black women. Greater role rewards reduced the risk of CAC progression over two years by fifty percent. This observed relationship existed with or without covariate adjustment. Role rewards were related to CAC progression in a similar beneficial direction for white women, but this effect was not statistically significant. In contrast, the number of roles and stresses from those roles did not relate to CAC progression in our study. Previous research has found that engaging in a variety of social roles improves well-being in black women (46). Moreover, a recent review (47) investigated the possible pathways from socioeconomic status (SES) to poor health in a broad sense and found that this pathway between SES and health was more influenced by a lack of psychosocial resources than by high stress levels. The benefits of psychosocial resources have been relatively understudied. Our findings thus highlight the clear need for more work examining how such resources in general, and the rewarding aspects of multiple roles in particular, may offer health benefits, particularly to women of color.

Why should rewards from multiple roles have a protective effect in black women? Midlife is a time of biological and often social changes for all women. For example, quantity and quality of roles may shift as children leave the house or return as adults. Elderly parents may be less able to care for themselves and rely more on their adult daughters for assistance. In the SWAN cohort, we found that black women tend to be more satisfied with their life than white women (48), but in our current analysis, black women indicated fewer rewards from the roles assessed here. A recent report on African American cardiac patients showed that patients with larger networks had more health support, better health behaviors, and higher coping efficacy (49). Older adults with multiple roles (50) and older adults with more active social lives (51) were found to be not just mentally but also physically healthier. In both of these studies, the effects were stronger in black than in white women. Healthy aging literature encourages participating actively in rewarding social roles (52). Other pathways beyond social factors and health behaviors may be important as well. As noted, key hormones, epinephrine and cortisol, are heightened under conditions of stress (28), and race differences have been observed in the impact of stress on cardiovascular recovery rates (30). However, it is unknown whether such hormones are affected by psychosocial resources, and whether such hormonal patterning varies by race. Much more work is needed to better understand biopsychosocial mechanisms and pathways linking psychosocial resources and CVD risk and, in particular, whether these mechanisms vary by race, and thus provide insight into the well-documented black-white disparities in CVD.

As noted, the literature suggests either no difference in prevalence of CAC between black and white women or a lower prevalence in black women (6). Our data are not consistent with this. We found that the prevalence of any CAC at baseline was significantly greater for blacks than for whites (Table 1), although the same proportion (18%) of black and white women experienced clinically relevant progression of 10 Agatston units or more over the two years of follow-up. Baseline CAC prevalence was more strongly related to two-year progression of CAC for white than for black women (Table 4), although reasons for this are unclear. It remains a task of future research to determine whether the observed protective effect of role rewards on CAC progression will also translate to decreased risk of clinical events, especially among black women. Given the well-documented excess risk of CVD morbidity and mortality among blacks relative to whites (1,2), it is critical to consider factors that may confer protective benefits on CVD risk over time in black women.

Limitations of the study should be mentioned. With just over two years of follow-up and only two assessments of CAC, it remains to be whether the amount of CAC progression observed will relate to future CVD events in this cohort or whether women without CAC progression will have a reduced risk of a CVD event over time. All participants with progression had a calcium score of at least 10 Agatston units at follow-up, and this level of calcification has been shown to double the risk of a CVD event (42). The number of women in our study using statins (see Table 1) was too low to investigate the effect of this medication on CAC progression. A recent meta-analysis found that statins do not impact coronary calcium (53). Furthermore, in MESA (54), statin use as well as BP medication use was positively associated with CAC progression, most likely indicating that the underlying hyperlidipedimia and/or hypertension is worse in subjects on medication than in other study participants, as the authors pointed out in the discussion. Despite statistically controlling for relevant risk factors, we cannot rule out the possibility of residual confounding. We asked about four possible roles. Although these may be the most common roles for women, other roles are possible, such as coach, friend, or volunteer. Stresses and rewards were assessed with one question for each role. The brevity of this assessment may raise the response rate, but does not provide any detail on the type of stress or reward. The simplicity of the question may capture the most important aspect of stress/reward, namely how a woman feels about the role. However, other summary measures of stress or reward could be explored. We chose to examine an average, because it puts all women on a comparable scale. A woman with one rewarding role, however, would look the same in our main analysis as a woman with three or even four rewarding roles. Due to the limited number of women who were caregivers, we could not look at caregiving in much detail. Data from the Nurses’ Health Study reported an increased risk of coronary heart disease (CHD) with number of hours spent caring for children/grandchildren(8) or for a disabled/ill spouse (55), but neither analysis found a relation between perceived stress or reward from caregiving and CHD.

Strengths of this study include a large number of black and white women from a well-characterized healthy cohort free of clinical cardiovascular disease. CAC was assessed in a standardized way at two time points, allowing assessment of relatively short-term progression of CAC. Several facets of role occupancy were assessed and evaluated in relation to CAC progression, and the breadth of SWAN data allowed us to consider a number of relevant confounders and covariates.

We observed a link between perceived rewards from multiple roles and early progression of CAC in black women. We have, therefore, identified a novel cardio-protective psychosocial factor in black midlife women that requires replication and further investigation. Given the serious risk of CVD that black women experience, further study of this and other protective factors appears warranted.

Acknowledgments

The Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN) has grant support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), DHHS, through the National Institute on Aging (NIA), the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) and the NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health (ORWH) (Grants NR004061; AG012505, AG012535, AG012531, AG012539, AG012546, AG012553, AG012554, AG012495). The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIA, NINR, ORWH or the NIH. SWAN Heart was supported by grants from the NHLBI (HL065581, HL065591, HL089862). The Chicago site of the SWAN Heart study was also supported by the Charles J. and Margaret Roberts Trust.

Clinical Centers: University of Michigan, Ann Arbor – MaryFran Sowers, PI; Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA – Joel Finkelstein, PI 1999 – present; Robert Neer, PI 1994 – 1999; Rush University, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL – Howard Kravitz, PI 2009 – present; Lynda Powell, PI 1994 – 2009; University of California, Davis/Kaiser – Ellen Gold, PI; University of California, Los Angeles – Gail Greendale, PI; Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY – Rachel Wildman, PI 2010; Nanette Santoro, PI 2004 – 2010; University of Medicine and Dentistry – New Jersey Medical School, Newark – Gerson Weiss, PI 1994 – 2004; and the University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA – Karen Matthews, PI.

NIH Program Office: National Institute on Aging, Bethesda, MD – Sherry Sherman 1994 – present; Marcia Ory 1994 – 2001; National Institute of Nursing Research, Bethesda, MD – Project Officer.

Central Laboratory: University of Michigan, Ann Arbor – Daniel McConnell (Central Ligand Assay Satellite Services).

Coordinating Center: University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA – Kim Sutton-Tyrrell, PI 2001 – present; New England Research Institutes, Watertown, MA - Sonja McKinlay, PI 1995 – 2001.

Steering Committee: Susan Johnson, Current Chair

Chris Gallagher, Former Chair

We thank the study staff at each site and all the women who participated in SWAN.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2011 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:e18–209. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182009701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gillum RF, Mussolino ME, Madans JH. Coronary heart disease incidence and survival in African-American women and men. the NHANES I epidemiologic follow-up study. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:111–118. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-2-199707150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klonoff EA. Disparities in the provision of medical care: An outcome in search of an explanation. J Behav Med. 2009;32:48–63. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9192-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Albert MA. Receipt of high-quality coronary heart disease care in the united states: All about being black or white: Comment on “Racial differences in admissions to high-quality hospitals for coronary heart disease”. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1216–1217. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jha AK, Varosy PD, Kanaya AM, et al. Differences in medical care and disease outcomes among black and white women with heart disease. Circulation. 2003;108:1089–1094. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000085994.38132.E5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orakzai SH, Orakzai RH, Nasir K, et al. Subclinical coronary atherosclerosis: Racial profiling is necessary! Am Heart J. 2006;152:819–827. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Everson-Rose S, Lewis TT. Psychosocial factors and cardiovascular diseases. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:469–500. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee S, Colditz G, Berkman L, Kawachi I. Caregiving to children and grandchildren and risk of coronary heart disease in women. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1939–1944. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.11.1939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bosma H, Peter R, Siegrist J, Marmot M. Two alternative job stress models and the risk of coronary heart disease. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:68–74. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.1.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaplan GA, Salonen JT, Cohen RD, Brand RJ, Syme SL, Puska P. Social connections and mortality from all causes and from cardiovascular disease: Prospective evidence from eastern Finland. Am J Epidemiol. 1988;128:370–380. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Orth-Gomer K, Horsten M, Wamala SP, et al. Social relations and extent and severity of coronary artery disease. the Stockholm female coronary risk study. Eur Heart J. 1998;19:1648–1656. doi: 10.1053/euhj.1998.1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawachi I, Colditz GA, Ascherio A, et al. A prospective study of social networks in relation to total mortality and cardiovascular disease in men in the USA. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1996;50:245–251. doi: 10.1136/jech.50.3.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tindle HA, Chang YF, Kuller LH, et al. Optimism, cynical hostility, and incident coronary heart disease and mortality in the women's health initiative. Circulation. 2009;120:656–662. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.827642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Troxel WM, Matthews KA, Bromberger JT, Sutton-Tyrrell K. Chronic stress burden, discrimination, and subclinical carotid artery disease in African American and Caucasian women. Health Psychol. 2003;22:300–309. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.3.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewis TT, Everson-Rose SA, Colvin A, Matthews K, Bromberger JT, Sutton-Tyrrell K. Interactive effects of race and depressive symptoms on calcification in African American and white women. Psychosom Med. 2009;71:163–170. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31819080e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewis TT, Everson-Rose SA, Powell LH, et al. Chronic exposure to everyday discrimination and coronary artery calcification in African-American women: The SWAN heart study. Psychosom Med. 2006;68:362–368. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000221360.94700.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diez Roux AV, Ranjit N, Powell LH, et al. Psychosocial factors and coronary calcium in adults without clinical cardiovascular disease. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:822–831. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-11-200606060-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matthews KA, Chang YF, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Edmundowicz D, Bromberger JT. Recurrent major depression predicts progression of coronary calcification in healthy women: Study of women's health across the nation. Psychosom Med. 2010;72:742–747. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181eeeb17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Janssen I, Powell LH, Matthews KA, et al. Depressive symptoms are related to progression of coronary calcium in midlife women: The study of women's health across the nation (SWAN) heart study. Am Heart J. 2011;161:1186–1191.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Low CA, Thurston RC, Matthews KA. Psychosocial factors in the development of heart disease in women: Current research and future directions. Psychosom Med. 2010;72:842–854. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181f6934f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rozario PA, Morrow-Howell N, Hinterlong JE. Role enhancement or role strain. Research on Aging. 2004;26:413–428. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Plaisier I, Beekman AT, de Bruijn JG, et al. The effect of social roles on mental health: A matter of quantity or quality? J Affect Disord. 2008;111:261–270. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Janzen BL, Muhajarine N. Social role occupancy, gender, income adequacy, life stage and health: A longitudinal study of employed Canadian men and women. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57:1491–1503. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00544-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haynes SG, Feinleib M. Women, work and coronary heart disease: Prospective findings from the framingham heart study. Am J Public Health. 1980;70:133–141. doi: 10.2105/ajph.70.2.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Orth-Gomer K, Leineweber C. Multiple stressors and coronary disease in women. the stockholm female coronary risk study. Biol Psychol. 2005;69:57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gallo LC, Troxel WM, Kuller LH, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Edmundowicz D, Matthews KA. Marital status, marital quality, and atherosclerotic burden in postmenopausal women. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:952–962. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000097350.95305.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barefoot JC, Gronbaek M, Jensen G, Schnohr P, Prescott E. Social network diversity and risks of ischemic heart disease and total mortality: Findings from the copenhagen city heart study. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161:960–967. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knox SS, Uvnas-Moberg K. Social isolation and cardiovascular disease: An atherosclerotic pathway? Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1998;23:877–890. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(98)00061-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kop WJ, Berman DS, Gransar H, et al. Social network and coronary artery calcification in asymptomatic individuals. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:343–352. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000161201.45643.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gillin JL, Mills PJ, Nelesen RA, Dillon E, Ziegler MG, Dimsdale JE. Race and sex differences in cardiovascular recovery from acute stress. Int J Psychophysiol. 1996;23:83–90. doi: 10.1016/0167-8760(96)00041-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bostock S, Hamer M, Wawrzyniak AJ, Mitchell ES, Steptoe A. Positive emotional style and subjective, cardiovascular and cortisol responses to acute laboratory stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.02.009. In Press, Corrected Proof. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sowers MF, Crawford S, Sternfeld B. SWAN: A multicenter, multiethnic, community-based cohort study of women and the menopausal transition. In: Lobo RA, Kelsey J, Marcus R, editors. Menopause: Biology and Pathobiology. San Diego, Calif. ; London: Academic; 2000. pp. 175–188. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Agatston AS, Janowitz WR, Hildner FJ, Zusmer NR, Viamonte M, Jr, Detrano R. Quantification of coronary artery calcium using ultrafast computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;15:827–832. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(90)90282-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rumberger JA, Brundage BH, Rader DJ, Kondos G. Electron beam computed tomographic coronary calcium scanning: A review and guidelines for use in asymptomatic persons. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74:243–252. doi: 10.4065/74.3.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sutton-Tyrrell K, Kuller LH, Edmundowicz D, et al. Usefulness of electron beam tomography to detect progression of coronary and aortic calcium in middle-aged women. Am J Cardiol. 2001;87:560–564. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)01431-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stephens MAP, Franks MM, Townsend AL. Stress and rewards in women's multiple roles: The case of women in the middle. Psychol Aging. 1994;9:45–52. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.9.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem. 1972;18:499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roberts RE. Reliability of the CES-D scale in different ethnic contexts. Psychiatry Res. 1980;2:125–134. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(80)90069-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boyd JH, Weissman MM, Thompson WD, Myers JK. Screening for depression in a community sample. understanding the discrepancies between depression symptom and diagnostic scales. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982;39:1195–1200. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290100059010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32:705–714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.LaMonte MJ, FitzGerald SJ, Church TS, et al. Coronary artery calcium score and coronary heart disease events in a large cohort of asymptomatic men and women. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162:421–429. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berry JD, Liu K, Folsom AR, et al. Prevalence and progression of subclinical atherosclerosis in younger adults with low short-term but high lifetime estimated risk for cardiovascular disease: The coronary artery risk development in young adults study and multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2009;119:382–389. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.800235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lumley T, Kronmal RA, Ma S. The Berkeley Electronic Press; 2006. Relative risk regression in medical research: Models, contrasts, estimators, and algorithms. http://www.bepress.com/uwbiostat/paper293. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu B, Wang Z. Estimating relative risks for common outcome using PROC NLP. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2008;90:179–186. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Black AR, Murry VM, Cutrona CE, Chen YF. Multiple roles, multiple lives: The protective effects of role responsibilities on the health functioning of African American mothers. Women Health. 2009;49:144–163. doi: 10.1080/03630240902915051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Matthews KA, Gallo LC, Taylor SE. Are psychosocial factors mediators of socioeconomic status and health connections? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1186:146–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brown C, Matthews KA, Bromberger J. How do African American and Caucasian women view themselves at midlife?1,2. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2005;35:2057–2075. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tkatch R, Artinian NT, Abrams J, et al. Social network and health outcomes among African American cardiac rehabilitation patients. Heart & Lung: The Journal of Acute and Critical Care. 2011;40:193–200. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2010.05.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Adelmann PK. Multiple roles and physical health among older adults. Research on Aging. 1994;16:142–166. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mendes de Leon CF, Glass TA, Berkman LF. Social engagement and disability in a community population of older adults. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2003;157:633–642. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Franklin NC, Tate CA. Lifestyle and successful aging: An overview. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine. 2009;3:6–11. [Google Scholar]

- 53.McEvoy JW, Blaha MJ, Defilippis AP, et al. Coronary artery calcium progression: An important clinical measurement? A review of published reports. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:1613–1622. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kronmal RA, McClelland RL, Detrano R, et al. Risk factors for the progression of coronary artery calcification in asymptomatic subjects: Results from the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA) Circulation. 2007;115:2722–2730. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.674143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee S, Colditz GA, Berkman LF, Kawachi I. Caregiving and risk of coronary heart disease in U.S. women: A prospective study. Am J Prev Med. 2003;24:113–119. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00582-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]