Abstract

The origin of the variation in the regioselectivity of the nucleophilic ring-opening of a series of bicyclic aziridinium ions derived from N-alkylprolinols was investigated by quantum chemical computations (M06-2X/6-31+G(d,p)—SMD). These aziridiniums differ only in the degree and the stereochemistry of fluoro substitution at C(4). With the azide ion as nucleophile, the ratio of the piperidine to the pyrrolidine product was computed. An electrostatic gauche effect influences the conformation of the adjoining five-membered ring in the fluorinated bicyclic aziridinium. This controls the regioselectivity of the aziridinium ring-opening.

Keywords: aziridinium, fluorine, gauche effect, nitrogen heterocycles, computational chemistry

1. Introduction

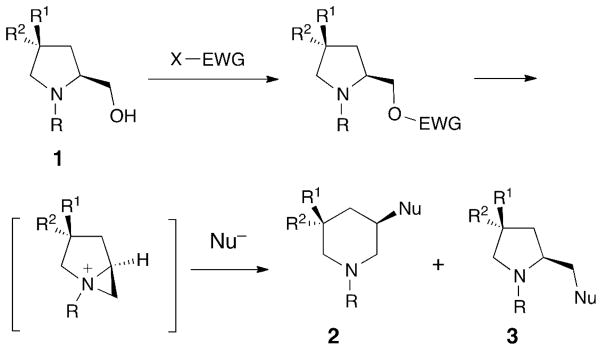

Many 3-aminopiperidine derivatives are bioactive compounds. The enantioselective synthesis of these substances is an area of active research [1]. A longstanding strategy for the preparation of 3-substituted piperidines 2 is ring expansion of N-protected prolinols 1 by a regioselective nucleophilic attack on bicyclic aziridinium intermediates generated by judicious activation of the hydroxyl group (Scheme 1) [2][3].

Scheme 1.

Nucleophilic Addition to an Aziridinium Intermediate Derived from N-Protected Prolinol 1.

Recently, the Cossy laboratory reported that 3-azidopiperidines could be accessed by this strategy starting from prolinols such as 1a–d (Table 1) by utilizing tetra-n-butylammonium azide in the presence of (diethylamino)difluorosulfonium tetrafluoroborate (XtalFluor-E™) as the activating reagent. The target amines can then be obtained by a Staudinger reduction [4][5]. Remarkably, among the fluorinated prolinols studied, the regioselectivity of the ring-opening of the corresponding bicyclic aziridinium is highly dependent on the extent of fluorination and the stereochemistry of the fluorine atoms at C(4) (Table 1). Thus, while the reaction of 1b yields the piperidine product with high selectivity (93:7; Table 1, entry 2) the reaction of the epimeric compound 1c is nonselective (Table 1, entry 3). Difluorinated prolinol 1d gives rise to the piperidine product as the major product with a ratio of 91:9 versus the pyrrolidine (Table 1, entry 4), a much higher selectivity than its nonfluorinated counterpart 1a, whose ring-opening is nonselective (Table 1, entry 1).

Table 1.

Ring expansion of nonfluorinated (1a) and fluorinated (1b–d) prolinol derivatives.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | R1 | R2 | Yield | 2a–d/3a–d | |

| 1 | 1a | H | H | 70% | 50/50 |

| 2 | 1b | H | F | 66% | 93/7 |

| 3 | 1c | F | H | 58% | 50/50 |

| 4 | 1d | F | F | 66% | 91/9 |

As reviewed recently by De Kimpe et al. [6] and Cossy et al. [7], the regiochemistry of the ring-opening of nonactivated aziridiniums, i.e. aziridiniums without an electron-withdrawing group on the nitrogen atom, is more sensitive to factors besides the substitution pattern on the ring than activated aziridiniums, including [8][9] the nature of the nucleophile [10–14] and the method of activation [4][15]. Nevertheless, we were 4 drawn to the intriguing problem posed by the product distributions of the ring-opening of the aziridiniums in Table 1, as the regioselectivity displays a wide variation that depends only on the degree and the stereochemistry of the fluorine atoms at C(4) of the prolinol precursors 1a–d. Although we previously showed that the regioselectivity of the ring-opening of bicyclic aziridiniums derived from prolinols could be enhanced to some extent by the use of bulky substituents at N and C(4) [4], it was less obvious how the fluorine atoms, with their minimal steric impact, exert such a dramatic influence on the product outcome. Moreover, while the regiochemistry of the ring-opening of aziridines fused to six-membered rings has been reported [16][17], the regioselectivity of the nucleophilic attack of the bicyclic aziridinium ions of type 1a–d has yet to be systematically investigated. We now present a computational analysis of these reactions, focusing on the influence of fluoro substitution on the conformation of the prolinols and the regioselectivity of the nucleophilic attack.

2. Computational Method

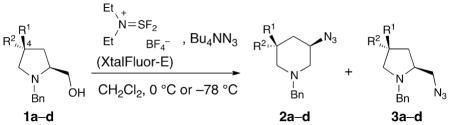

All of the computations were performed on Gaussian 09 [18]. The aziridinium and the transition structures (TSs) for the reactions with an azide ion were modeled computationally. Cossy et al. have demonstrated the intermediacy of the aziridinium in these reactions [5]. The reactions of 1a–d proceed under kinetic rather than thermodynamic control [4][17]. The geometries were optimized at the M06-2X/6-31+G(d,p) level of theory [19][20] in conjunction with the SMD continuum solvation model [21] using dichloromethane as solvent. Each structure was characterized as either an energy minimum or a transition structure by a frequency computation. To study the influence of the C4-substituent of the prolinol on product outcome, the nonfluorinated (4a), monofluorinated (4b and 4c), and difluorinated (4d) bicyclic aziridiniums were studied (Scheme 2). The N-benzyl groups in the experimental substrates were replaced by N-methyl groups in the modeling.

Scheme 2.

The Structures of Aziridiniums 4a–d Studied by Computation in This Work.

3. Results and Discussion

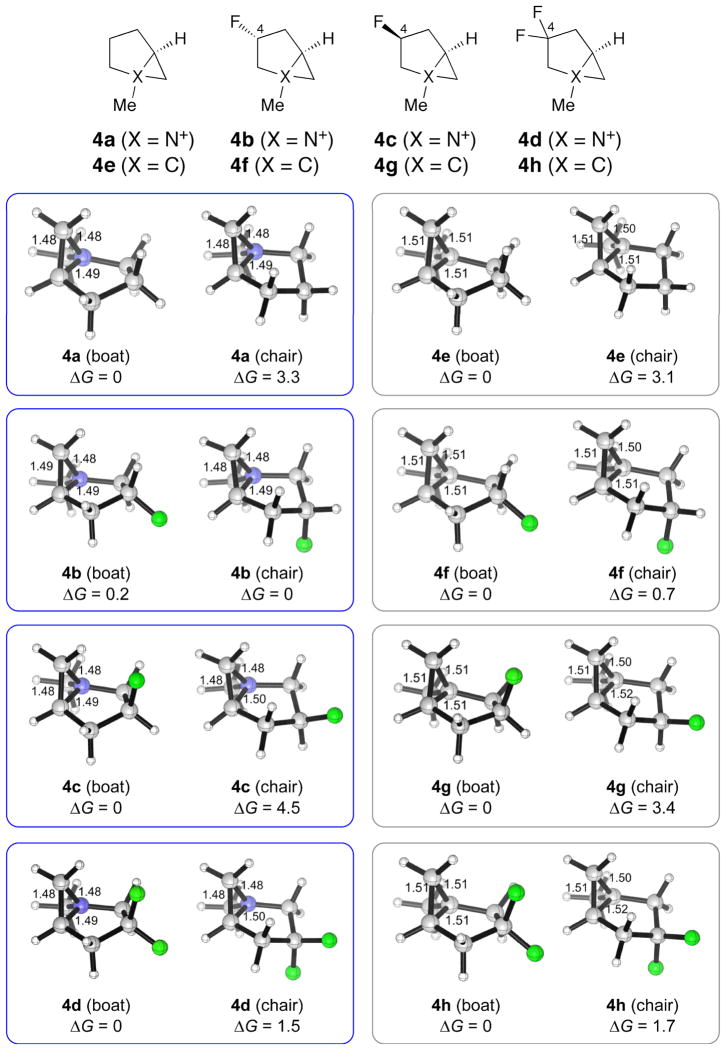

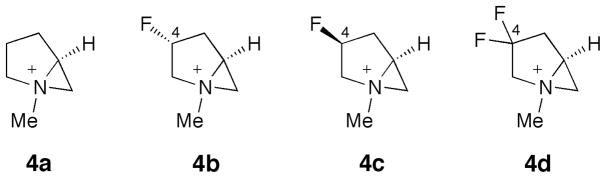

Two conformations of 4a–d were found (Fig. 1). The conformers in which the five-membered ring exhibits the 4E and the E4 conformations are termed the boat and the chair, respectively. To fully understand the conformational energetics of the azabicycles, we also studied the boat and the chair forms of the carba analogues 4e–h. The computations show that for 4a, 4c and 4d, the boat conformers are more stable than the chairs by 1.5–4.5 kcal/mol, whereas 4b shows the opposite preference, if slightly, with the chair being the more stable. The carba analogues, on the other hand, favor the boat forms regardless of fluoro substitution. The computed preferences for the boat conformation in structures analogous to 4c, where C(4) bears an electronegative atom [22], and in the bicyclo[3.1.0]cyclohexanes [23–26] are supported by several X-ray crystallographic structures, some of which are illustrated in Fig. 2.

Fig. 1. Structures and free energies of the boat and chair conformers of aziridinium ions 4a – d (boxed in blue) and their carba analogues4e–h (boxed in grey).

The relative Gibbs free energies of the two conformers are given in kcal/mol.

Fig. 2. Crystallographic structures of molecules or ions containing the bicyclo[3.1.0]cyclohexane ring (B–D) or its 1-aza analogue (A), retrieved from the Cambridge Crystallographic Structural Database.

For (A), the mirror image of the reported structure is shown to maintain comparability with the structure of 4c. 7 Reference codes: A: QOZDEO (ref. [22]); B: HEBCHN (ref. [23]); C: KIXSAL (ref. [24]); D: EBUXAB (ref. [25]).

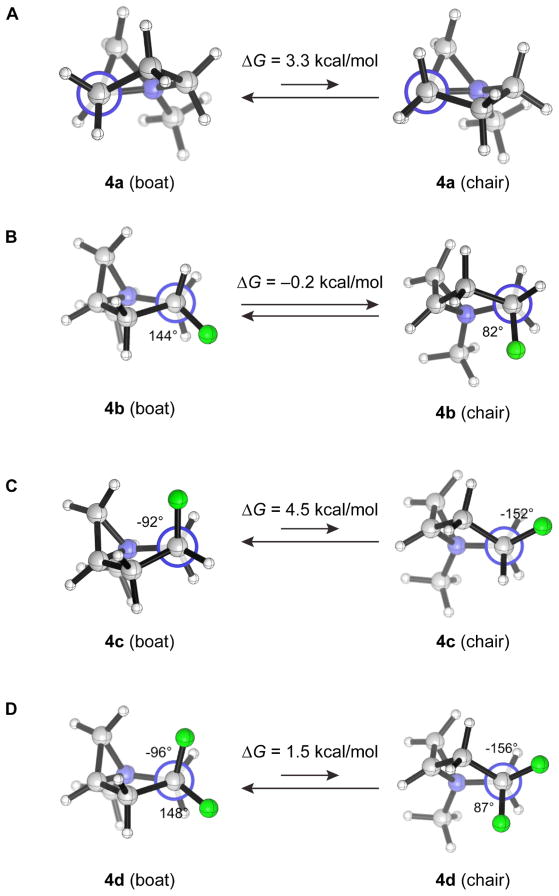

The chair conformers of the nonfluorinated aziridinium 4a and the fused carbocyclic rings in 4e–h are disfavored by eclipsing strain which is not found in the boat forms. The chair conformers of these bicyclic rings contain two pairs of eclipsing interactions between a pseudoaxial C–H bond in the five-membered ring (as shown in Fig. 3, A for 4a) and either an N+–R bond or a C–H bond at one of the ring junctions (not shown), as documented previously [27–29]. When C(4) is fluorinated, the so-called electrostatic gauche effect [30][31], i.e. the preference of fluorine to be gauche, rather than anti, to the quaternary ammonium nitrogen, constitutes the second important conformation-determining factor. Thus, in 4c, fluoro substitution enhances the stability of the boat form (shown in Fig. 3, C) relative to the chair (4.5 kcal/mol, compare with 3.3 kcal/mol in favor of the boat for nonfluorinated 4a) due to the synclinal disposition of the pseudoaxial fluorine to the ammonium nitrogen in the boat, while in 4b, the gauche effect is found in the chair (Fig. 3, B) and causes this conformer to be less unfavorable, diminishing the energy difference between the conformers compared with that in 4a. Both the boat and the chair forms of 4d accommodate one gauche F–C–C–N+ interaction, and the intrinsic boat preference of the fused ring system dictates the conformational equilibrium. The role of the gauche effect in biasing the conformation of the fluorinated bicyclic aziridiniums here is directly analogous to that in influencing the conformational behavior of 4-fluoroproline [32][33], 3-fluoropiperidine and its derivatives [34], and four- and eight-membered ring systems [35].

Fig. 3. (A) Newman projection of4a along C(3)–C(2) bond, showing one of the two eclipsing interactions in the chair conformation. (B–D) Newman projections along the C(4)–C(5) bond of 4b, 4c and 4d.

The F–C(4)–C(5)–N+ dihedral angles are annotated.

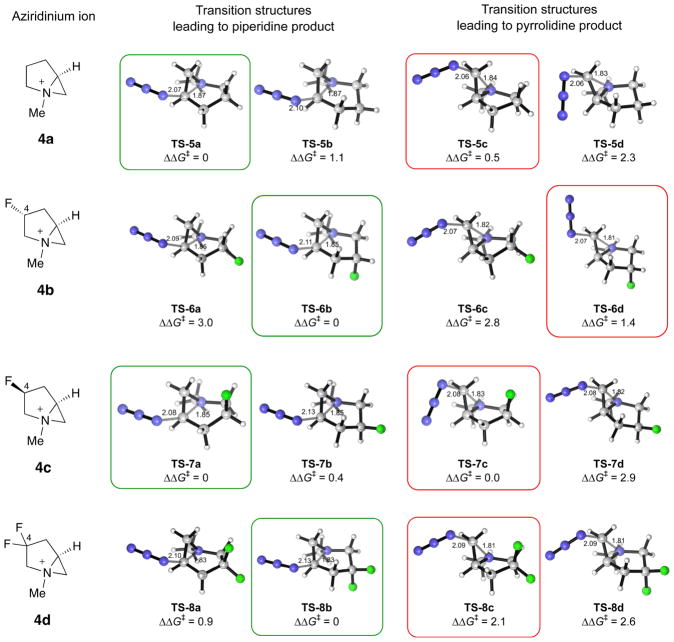

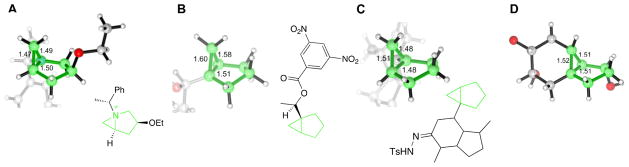

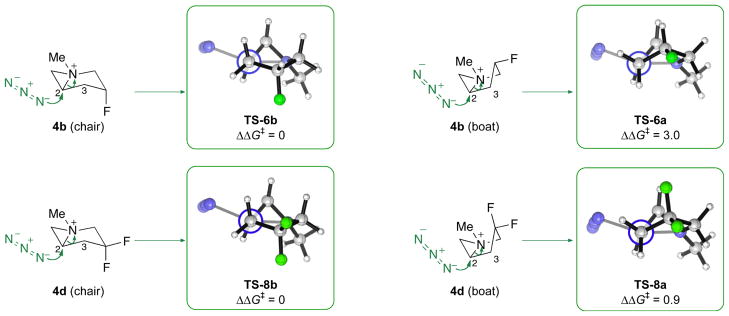

The transition structures for the nucleophilic ring-opening step of 4a–d by the azide ion leading to 3-azidopiperidine and 2-(azidomethyl)pyrrolidine were then studied. These were optimized by starting from both the boat and the chair conformations as well as different dihedral angles at which the azide approaches the aziridinium. The lowest-energy chair and boat forms of the regioisomeric transition structures are illustrated in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Optimized geometries and relative free energies(ΔΔG‡, in kcal/mol) of the lowest-energy transition structures for the nucleophilic ring-opening reactions of aziridinium ions 4a–d by azide.

Type a and type c structures feature the azabicycle in a boat-like conformation, while type b and type d structures are chair-like. The lowest-energy transition structures leading to the piperidine and the pyrrolidine products are boxed in green and red, respectively.

For all of the aziridiniums studied, good agreement was found between the relative free energies of the regioisomeric transition structures and the experimental selectivity (Table 2). For the non-fluorinated 4a, the energy difference of 0.5 kcal/mol between the TS-5a and TS-5c predicts a low selectivity of 72:28 in favor of the piperidine product, comparing well with the experimental ratio of 50:50 for reaction of prolinol 1a. The dependence of the regioselectivity on the configuration of the fluorinated stereocenter at C(4) was also accounted for by the computations. Thus, the nonselective reaction from 1c was reproduced as TS-7a and TS-7c, derived from 4c, were found to be isoenergetic. Inverting the configuration at C(4) of 4c widens the energy difference between the transition structures, as TS-6b is now more stable than TS-6d by 1.4 kcal/mol, corresponding to a selectivity of 97:3 favoring the piperidine product at −78 °C. The high regioselectivity for difluorinated 4d was also reproduced computationally.

Table 2.

Free energies of activation (ΔG‡) for the formation of the piperidine product and the regioselectivities of the nucleophilic ring-opening step of 4a–d. The regioselectivities were computed using the boxed transition structures in Fig. 4 at the experimental temperature (0 °C for 4a, −78 °C for 4b–d).

| Entry | Aziridinium ion | ΔG‡ (kcal/mol) | piperidine/pyrrolidine ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| expt | computed | |||

| 1 | 4a | 16.4 | 50:50 | 72:28 |

| 2 | 4b | 12.0 | 93:7 | 98:2 |

| 3 | 4c | 14.5 | 50:50 | 50:50 |

| 4 | 4d | 12.0 | 91:9 | > 99:1 |

The results in Fig. 4 reveal two points of consideration that shed light on the origin of the regioselectivity. First, the same conformation was adopted by the aziridinium in the reactant and in the lowest-energy transition structures, except in the case of 4d. Thus, the non-regioselective ring-opening of 4a (and 4c) was predicted to proceed through TS-5a (TS-7a) and TS-5c (TS-7c), which features a boat-like conformation of the aziridinium analogous to that of 4a (4c). Bicyclic aziridinium 4b also reacts predominantly via the chair-like TS-6b and TS-6d. The boat-like TS-6a and TS-6c are at least 2.8 kcal/mol less stable than TS-6b, representing an amplified difference in conformational energy compared with that found for the reactant (0.2 kcal/mol, Fig. 2). The conformational preferences of 4d and its derived transition structures are less uniform. The most stable transition structure was found to be the chair-like TS-8b, which differs from the boat-like TS-8a by 0.9 kcal/mol, although the lowest-energy transition structure leading to the pyrrolidine, TS-8c, preserves the boat conformation. Second, all of the chair-like transition structures (types b and d) open preferentially to give the piperidine product with high selectivity while the boat-like structures (types a and c) are nonselective except for 4d. Thus, the chair conformer TS-5b for the piperidine product is 1.2 kcal/mol more stable than TS-5d, and the corresponding difference between TS-7b and TS-7d is 2.5 kcal/mol. The computations, therefore, revealed that no regioselectivity was experimentally observed with prolinols 1a and 1c because the chair conformers of these aziridiniums are energetically inaccessible, being at least 3.3 and 4.5 kcal/mol higher in energy than the most stable, boat conformer.

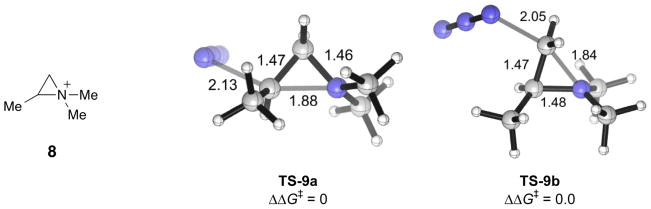

Why do the chair conformers of the bicyclic aziridiniums open regioselectively at the more substituted end? The preference of the azide nucleophile to react at the more substituted carbon of 4a–d may seem surprising [36]. To understand the role of the adjoining five-membered ring in influencing the regioselectivity of the nucleophilic attack of the bicyclic aziridinium, we have computed the transition structures for the ring-opening of the model aziridinium ion 8 (Fig. 5). This monocyclic compound preserves the substitution on nitrogen and on C(2) by methyl groups. TS-9a, in which the azide ion reacts at the methyl-substituted C(2), is analogous to the transition structures leading to the piperidine products, and TS-9b corresponds to transition structures giving rise to the pyrrolidine products. The computations show that these transition structures are isoenergetic. Thus, contrary to expectations from steric effects, the basic bicyclic aziridinium moiety in 4a–d has no intrinsic regioselectivity with azide as the nucleophile. Presumably, the longer length of the partial bond between C(2) and the nucleophilic nitrogen in TS-9a (2.13 Å) compared with that in TS-9b (2.05 Å) reduces the steric strain experienced by the approaching nucleophile, making TS-9a less disfavored than expected.

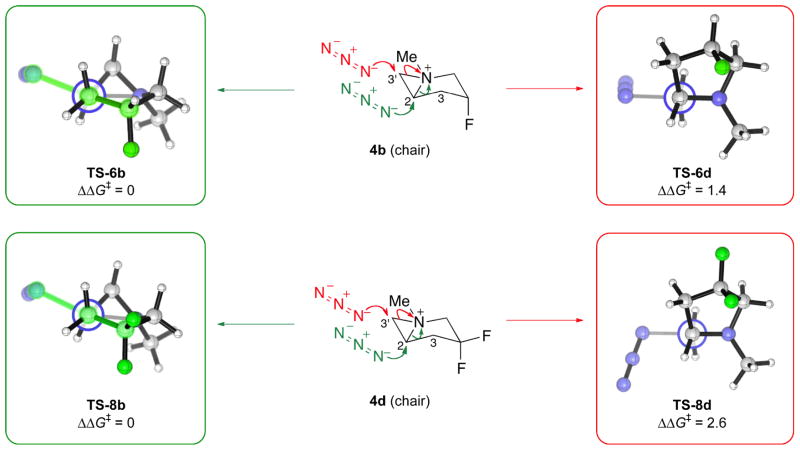

Fig. 5.

The structure of model aziridinium 8, and the optimized transition structures, TS-9a and TS-9b, for the nucleophilic ring-opening step by azide.

Since the model aziridinium 8 opens non-regioselectively, any regioselectivity in the ring-opening of the bicyclic aziridinium must be due to the presence of the pyrrolidine ring. To understand why the piperidine TSs are lower in energy than the pyrrolidine TSs when the bi-cycle is in the chair conformation, it proved instructive to examine the Newman projections of these TSs along the C–C bond geminal to the breaking C–N+ bond of the aziridinium moiety. These Newman projections are shown in Fig. 6 for the chair-like TS-6b and TS-8b, which, being lower in energy than the chair-like TS-6d and TS-8d by 1.4 and 2.6 kcal/mol (Fig. 4), are responsible for the formation of the piperidine as the major product. In the optimized structures of TS-6b and TS-8b, the C(3)–C(4) bond is placed antiperiplanar to the partially formed C–N bond as highlighted. This stereoelectronic effect might serve to stabilize TS-6b and TS-8b with respect to TS-6d and TS-8d, which do not have these interactions.

Fig. 6. Newman projections along the C–C bond geminal to the breaking C–N+ bond of the ring-opening transition structures of4b (chair) and 4d (chair).

The transition structures for ring-opening at C(2), leading to piperidine, and C(3′), leading to pyrrolidine, are colored green and red, respectively.

It is also of interest to note that the chair-like TS-6b and TS-8b are more stable than the their boat-like conformers TS-6a and TS-8a (Fig. 7), although these differences do not impact the product outcome since both type a and type b TSs lead to the same piperidine product. The geometries in the vicinity of the partial bonds as revealed by the Newman projections in Fig. 7 reveal a more staggered arrangement in TS-6b and TS-8b. This is reminiscent of the effect of transition state staggering, or torsional steering, which originates from the preference for a maximally staggered arrangement of bonds in transition structures (as well as reactants and products). This effect is responsible for inducing contra-steric stereoselectivity [37], not least in the well-known case of the totally stereoselective additions to 2,6-disubstituted 1,3-dioxin-4-ones reported by Seebach [37a].

Fig. 7. Newman projections along the C3–C2 bond of the boat-like conformers (TS-6a and TS-8a) and the chair-like conformers (TS-6b and TS-8b) of the ring-opening transition structure of 4b and 4d.

These Newman projections show that the bonds around the reacting carbon (C(2)) are more staggered in the chair-like conformers (type b) than in the boat-like conformers (type a).

In summary, the computations reported here have delineated the effect of fluoro substitution at C4 of prolinols 1a–d on the regioselectivities of the nucleophilic ring-opening of bicyclic aziridinium ions derived from the prolinols. The azabicycle normally prefers the boat conformation, but the fluorine–ammonium gauche effect can arise as an additional factor that tips the energy balance to the chair if the fluorine atom on C(4) is incorporated with the appropriate stereochemistry. The computed transition structures show that for 4a–c, the chair conformers of the bicyclic aziridiniums are more discriminating than the boats in their ring-opening to give the piperidine products, regardless of fluoro substitution. The high regioselectivity observed with fluorinated prolinol 1b arises from the predominance of chair-like transition structures due to the favorable gauche effect. The nonselectivities in the ring-opening of the bicyclic aziridinium starting from epimeric 1c and nonfluorinated 1a are attributed to the prevalence of boat-like transition structures. Fluorine, therefore, acts as a device for conformational control through the electrostatic gauche effect. The exploitation of these effects in organic and biological chemistry is currently an emerging area [38–41]. Our experimental and theoretical work illustrates how these effects result in enhanced regiocontrol in the ring-opening chemistry of bicyclic aziridiniums, complementing much of the research to date on the stereoelectronic effects of fluorine, which mostly focuses on their stereochemical ramifications [42].

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, National Institutes of Health (GM36700) for financial support of this research. We also thank UCLA Institute for Digital Research and Education and the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE), supported by National Science Foundation grant number OCI-1053575, for computational resources.

Dedicated to Professor Dieter Seebach on the occasion of his 75th birthday

Contributor Information

Yu-hong Lam, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of California, Los Angeles, 607 Charles E. Young Drive East, Los Angeles, California 90095-1569, USA, phone: +1-310-206-0515; fax: +1-310-206-1843;.

Kendall N. Houk, Email: houk@chem.ucla.edu, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of California, Los Angeles, 607 Charles E. Young Drive East, Los Angeles, California 90095-1569, USA, phone: +1-310-206-0515; fax: +1-310-206-1843;

Janine Cossy, Email: janine.cossy@espci.fr, Laboratoire de Chimie Organique, ESPCI ParisTech, CNRS (UMR 704), 10 rue Vauquelin, 75231 Paris Cedex 05, France, fax: +33-1-40794660;.

Domingo Gomez Prado, Laboratoire de Chimie Organique, ESPCI ParisTech, CNRS (UMR 704), 10 rue Vauquelin, 75231 Paris Cedex 05, France, fax: +33-1-40794660;.

Anne Cochi, Laboratoire de Chimie Organique, ESPCI ParisTech, CNRS (UMR 704), 10 rue Vauquelin, 75231 Paris Cedex 05, France, fax: +33-1-40794660;.

References

- 1.Berggren K, Vindebro R, Bergström C, Spoerry C, Persson H, Fex T, Kihlberg J, von Pawel-Rammingen U, Luthman K. J Med Chem. 2012;55:2549. doi: 10.1021/jm201517a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Sakurai R, Sakai K, Kodama K, Yamaura M. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2012;23:221. [Google Scholar]; Kumaraswamy G, Pitchaiah A. Tetrahedron. 2011;67:2536. [Google Scholar]; Rodriguez J Gonzalez, Juan B Vidal, Gispert L Vidal, Tana J Bach. WO2012069202. PCT Int Appl. 2012:A1.; Blomgren PA, Currie KS, Mitchell SA, Brittelli DR. WO2010068788. PCT Int Appl. 2010:A1.; Kuroita T, Imaeda Y, Iwanaga K, Taya N, Tokuhara H, Fukase Y. WO2009154300. PCT Int Appl. 2009:A2.; Christopher RJ, Paul C. ZA2008002857A S African Pat. 2009; Nakahira H, Hochigai H, Ikuma Y, Takamura M. WO2008136457. PCT Int Appl. 2008:A1.; Robins K, Bornscheuer U, Hoehne M. WO2008028654. PCT Int Appl. 2008:A1.; Martini E, Ghelardini C, Dei S, Guandalini L, Manetti D, Melchiorre M, Norcini M, Scapecchi S, Teodori E, Romanelli MN. Bioorg Med Chem. 2008;16:1431. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tymoshenko DO. Arkivoc. 2011:329. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bilke JL, Moore SP, O’Brien P, Gilday J. Org Lett. 2009;11:1935. doi: 10.1021/ol900366m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Dechamps I, Gomez Pardo D, Cossy J. Arkivoc. 2007:38. [Google Scholar]; Dondoni A, Richichi B, Marra A, Perrone D. Synlett. 2004:1711. [Google Scholar]; Cossy J, Mirguet O, Gomez Pardo D, Desmurs JR. Eur J Org Chem. 2002:3543. [Google Scholar]; Cossy J, Gomez Pardo D. Chemtracts—Org Chem. 2002;15:579. [Google Scholar]; Cossy J, Mirguet O, Gomez Pardo D. Synlett. 2001:1575. [Google Scholar]; Lee J, Hoang T, Lewis S, Weissman SA, Askin D, Volante RP, Reider PJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:6223. [Google Scholar]; Cossy J, Mirguet O, Gomez Pardo D, Desmurs JR. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:5705. [Google Scholar]; Cossy J, Dumas C, Gomez Pardo D. Eur J Org Chem. 1999:1693. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cochi A, Gomez Pardo D, Cossy J. Eur J Org Chem. 2012:2023. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cochi A, Gomez Pardo D, Cossy J. Org Lett. 2011;13:4442. doi: 10.1021/ol201769b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stanković S, D’hooghe M, Catak S, Eum H, Waroquier M, Van Speybroeck V, De Kimpe N, Ha HJ. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:643. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15140a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Metro T-X, Duthion B, Gomez Pardo D, Cossy J. Chem Soc Rev. 2010;39:89. doi: 10.1039/b806985a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Banks HD. J Org Chem. 2006;71:8089. doi: 10.1021/jo061255j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Helten H, Schirmeister T, Engels B. J Org Chem. 2004;70:233. doi: 10.1021/jo048373w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.D’hooghe M, Catak S, Stanković S, Waroquier M, Kim Y, Ha HJ, Van Speybroeck V, De Kimpe N. Eur J Org Chem. 2010:4920. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yun SY, Catak S, Lee WK, D’hooghe M, De Kimpe N, Van Speybroeck V, Waroquier M, Kim Y, Ha HJ. Chem Commun. 2009:2508. doi: 10.1039/b822763b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim Y, Ha HJ, Yun SY, Lee WK. Chem Commun. 2008:4363. doi: 10.1039/b809124b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Oosten EM, Gerken M, Hazendonk P, Shank R, Houle S, Wilson AA, Vasdev N. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011;52:4114. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Catak S, D’hooghe M, De Kimpe N, Waroquier M, Van Speybroeck V. J Org Chem. 2009;75:885. doi: 10.1021/jo902493w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Catak S, D’hooghe M, Verstraelen T, Hemelsoet K, Van Nieuwenhove A, Ha HJ, Waroquier M, De Kimpe N, Van Speybroeck V. J Org Chem. 2010;75:4530. doi: 10.1021/jo100687q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karban J, Kroutil J, Buděšínský M, Sýkora J, Císařová I. Eur J Org Chem. 2009:6399. doi: 10.1021/jo1000912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kroutil J, Trnka T, Buděšínský M, Černý M. Eur J Org Chem. 2002:2449. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Scalmani G, Barone V, Mennucci B, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Caricato M, Li X, Hratchian HP, Izmaylov AF, Bloino J, Zheng G, Sonnenberg JL, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Vreven T, Montgomery JA, Jr, Peralta JE, Ogliaro F, Bearpark M, Heyd JJ, Brothers E, Kudin KN, Staroverov VN, Keith T, Kobayashi R, Normand J, Raghavachari K, Rendell A, Burant JC, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Cossi M, Rega N, Millam JM, Klene M, Knox JE, Cross JB, Bakken V, Adamo C, Jaramillo J, Gomperts R, Stratmann RE, Yazyev O, Austin AJ, Cammi R, Pomelli C, Ochterski JW, Martin RL, Morokuma K, Zakrzewski VG, Voth GA, Salvador P, Dannenberg JJ, Dapprich S, Daniels AD, Farkas O, Foresman JB, Ortiz JV, Cioslowski J, Fox DJ. ‘Gaussian 09’ (Revision C.01) Gaussian Inc; Wallingford CT: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao Y, Truhlar D. Theor Chem Acc. 2008;120:215. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao Y, Truhlar DG. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41:157. doi: 10.1021/ar700111a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marenich AV, Cramer CJ, Truhlar DG. J Phys Chem B. 2009;113:6378. doi: 10.1021/jp810292n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Ribeiro RF, Marenich AV, Cramer CJ, Truhlar DG. J Phys Chem B. 2011;115:14556. doi: 10.1021/jp205508z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Graham MA, Wadsworth AH, Thornton-Pett M, Rayner CM. Chem Commun. 2001:966. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steinberg NG, Rasmusson GH, Reynolds GF, Springer JP, Arison BH. J Org Chem. 1979;44:3416. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paquette LA, Friedrich D, Rogers RD. J Org Chem. 1991;56:3841. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hodgson DM, Chung YK, Paris JM. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:8664. doi: 10.1021/ja047346k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grostic MF, Duchamp DJ, Chidester CG. J Org Chem. 1971;36:2929. doi: 10.1021/jo00821a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheong PHY, Yun H, Danishefsky SJ, Houk KN. Org Lett. 2006;8:1513. doi: 10.1021/ol052862g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kang P, Choo J, Jeong M, Kwon Y. J Mol Struct. 2000;519:75. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mastryukov VS, Osina EL, Vilkov LV, Hilderbrandt RL. J Am Chem Soc. 1977;99:6855. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gooseman NEJ, O’Hagan D, Peach MJG, Slawin AMZ, Tozer DJ, Young RJ. Angew Chem. 2007;119:6008. doi: 10.1002/anie.200700714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:5904. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Briggs CRS, Allen MJ, O’Hagan D, Tozer DJ, Slawin AMZ, Goeta AE, Howard JAK. Org Biomol Chem. 2004;2:732. doi: 10.1039/b312188g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gerig JT, McLeod RS. J Am Chem Soc. 1973;95:5725. doi: 10.1021/ja00798a046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DeRider ML, Wilkens SJ, Waddell MJ, Bretscher LE, Weinhold F, Raines RT, Markley JL. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:2497. doi: 10.1021/ja0166904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun A, Lankin DC, Hardcastle K, Snyder JP. Chem Eur J. 2005;11:1579. doi: 10.1002/chem.200400835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Lankin DC, Chandrakumar NS, Rao SN, Spangler DP, Snyder JP. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:3356. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gooseman NEJ, O’Hagan D, Slawin AMZ, Teale AM, Tozer DJ, Young RJ. Chem Commun. 2006:3190. doi: 10.1039/b606334a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ring-opening of 2-(1-alkenyl)-substituted aziridiniums is known to occur preferentially at the more substituted carbon: Jarvis SBD, Charette AB. Org Lett. 2011;13:3830. doi: 10.1021/ol201349k.D’hooghe M, Van Speybroeck V, Van Nieuwenhove A, Waroquier M, De Kimpe N. J Org Chem. 2007;72:4733. doi: 10.1021/jo0704210.Lee BK, Kim MS, Hahm HS, Kim DS, Lee WK, Ha H-J. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:8393.

- 37.a) Seebach D, Zimmermann J, Gysel U, Ziegler R, Ha TK. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110:4763. [Google Scholar]; b) Iafe RG, Houk KN. Org Lett. 2006;8:3469. doi: 10.1021/ol061085x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Ando K, Green NS, Li Y, Houk KN. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:5334. [Google Scholar]; d) Lucero MJ, Houk KN. J Org Chem. 1998;63:6973. doi: 10.1021/jo980760g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Martinelli MJ, Peterson BC, Khau VV, Hutchison DR, Leanna MR, Audia JE, Droste JJ, Wu YD, Houk KN. J Org Chem. 1994;59:2204. [Google Scholar]; f) Wu YD, Houk KN, Trost BM. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:5560. [Google Scholar]; g) Houk KN, Paddon-Row MN, Rondan NG, Wu YD, Brown FK, Spellmeyer DC, Metz JT, Li Y, Loncharich RJ. Science. 1986;231:1108. doi: 10.1126/science.3945819. See also ref. [27] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hunter L, Jolliffe KA, Jordan MJT, Jensen P, Macquart RB. Chem Eur J. 2011;17:2340. doi: 10.1002/chem.201003320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zimmer LE, Sparr C, Gilmour R. Angew Chem. 2011;123:12062. doi: 10.1002/anie.201102027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:11860. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hunter L. Beilstein J Org Chem. 2010;6 doi: 10.3762/bjoc.6.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O’Hagan D. Chem Soc Rev. 2008;37:308. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chia PW, Livesey MR, Slawin AMZ, van Mourik T, Wyllie DJA, O’Hagan D. Chem Eur J. 2012;18:8813. doi: 10.1002/chem.201200071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Durantie E, Bucher C, Gilmour R. Chem Eur J. 2012;18:8208. doi: 10.1002/chem.201200468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Tanzer EM, Schweizer WB, Ebert MO, Gilmour R. Chem Eur J. 2012;18:2006. doi: 10.1002/chem.201102859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Um JM, DiRocco DA, Noey EL, Rovis T, Houk KN. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:11249. doi: 10.1021/ja202444g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Sparr C, Salamanova E, Schweizer WB, Senn HM, Gilmour R. Chem Eur J. 2011;17:8850. doi: 10.1002/chem.201100644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Campbell NH, Smith DL, Reszka AP, Neidle S, O’Hagan D. Org Biomol Chem. 2011;9:1328. doi: 10.1039/c0ob00886a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Yamamoto I, Deniau GP, Gavande N, Chebib M, Johnston GAR, O’Hagan D. Chem Commun. 2011;47:7956. doi: 10.1039/c1cc12141c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Bucher C, Gilmour R. Angew Chem. 2010;122:8906. doi: 10.1002/anie.201004467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:8724. [Google Scholar]; Sparr C, Gilmour R. Angew Chem. 2010;122:6670. doi: 10.1002/anie.201003734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:6520. [Google Scholar]; Díaz J, Goodman JM. Tetrahedron. 2010;66:8021. [Google Scholar]; Paul S, Schweizer WB, Ebert MO, Gilmour R. Organometallics. 2010;29:4424. [Google Scholar]; Sparr C, Schweizer WB, Senn HM, Gilmour R. Angew Chem. 2009;121:3111. doi: 10.1002/anie.200900405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:3065. [Google Scholar]; Tredwell M, Luft JAR, Schuler M, Tenza K, Houk KN, Gouverneur V. Angew Chem. 2008;120:363. doi: 10.1002/anie.200703465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:357. [Google Scholar]; Mathad RI, Jaun B, Floegel O, Gardiner J, Loeweneck M, Codee JDC, Seeberger PH, Seebach D, Edmonds MK, Graichen FHM, Abell AD. Helv Chim Acta. 2007;90:2251. [Google Scholar]; Mathad RI, Gessier F, Seebach D, Jaun B. Helv Chim Acta. 2005;88:266. See also ref. [30–35] [Google Scholar]