Abstract

Alcohol is a known teratogen that is estimated to affect 2–5% of the births in the U.S. Prenatal alcohol exposure can produce physical features such as facial dysmorphology, physiological alterations such as cell loss in the central nervous system (CNS), and behavioral changes that include hyperactivity, cognitive deficits, and motor dysfunction. The range of effects associated with prenatal alcohol exposure is referred to as fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD). Despite preventative measures, some women continue to drink while pregnant. Therefore, identifying interventions that reduce the severity of FASD is critical. This study investigated one such potential intervention, vitamin D3, a nutrient that exerts neuroprotective properties. The present study determined whether cholecalciferol, a common vitamin D3 nutritional supplement, could serve as a means of mitigating alcohol-related learning deficits. Using a rat model of FASD, cholecalciferol was given before, during, and after 3rd trimester equivalent alcohol exposure. Three weeks after cholecalciferol treatment, subjects were tested on a serial spatial discrimination reversal learning task. Animals exposed to ethanol committed significantly more errors compared to controls. Cholecalciferol treatment reduced perseverative behavior that is associated with developmental alcohol exposure in a dose-dependent manner. These data have important implications for the treatment of FASD and suggest that cholecalciferol may reduce some aspects of FASD.

Keywords: fetal alcohol, vitamin D3, behavior, treatment, nutrition, ethanol

1. Introduction

Alcohol is a known teratogen that may affect 2–5% of the U.S. population [1]. Consuming alcohol during pregnancy can disrupt fetal development, leading to a range of physical, neuropathological, and behavioral alterations referred to as fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD) [2]. In fact, prenatal alcohol exposure is the leading known cause of preventable intellectual disabilities [3]. Despite prevention efforts, some women continue to drink while pregnant, making it necessary to identify effective interventions to reduce the severity of FASD. The present study examines the therapeutic potential of vitamin D3, specifically cholecalciferol. 1,25-hydroxyvitamin D3 affects production of neurotrophins, neurotransmitters, and various proteins that are important throughout brain development [4, 5]. Alcohol exposure can also decrease 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 levels in humans and animals [6, 7], including pregnant females [8], thus vitamin D3 deficiencies may contribute to FASD [9, 10]. In fact, prenatal vitamin D3 deficiency produces similar effects to those seen following developmental alcohol exposure [11–13]. However, even in the absence of a deficiency, 1,25-hydroxyvitamin D3 displays neuroprotective properties, such as upregulating neurotrophin levels (e.g. glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), neurotrophin (NT)-3, NT4/5, nerve growth factor (NGF)) to reduce infarct volumes following middle cerebral artery ligation in rats [14], and to enhance synaptic transmission in the hippocampus [4, 5, 15]. Therefore, we investigated whether cholecalciferol, the common vitamin D3 nutritional supplement, could serve as a means of mitigating alcohol-related behavioral alterations.

2. Material and Methods

Sprague-Dawley rat pups were exposed to alcohol during the 3rd trimester brain growth spurt which occurs postnatally in the rat (postnatal days (PD) 4 through 9) [16, 17]. This is a period of development when the brain is particularly vulnerable to alcohol exposure. Subjects were randomly assigned to one of 8 treatment groups on PD 1. Ethanol-exposed subjects were treated with a total of 5.25 g/kg/day ethanol (11.9% v/v) from PD 4–9 via 2 intragastric intubations, 2 hrs apart [18]. Two additional milk feedings followed each day, delivered at 2 hr intervals. Controls received sham intubations. Subjects were subcutaneously injected with 0 (vehicle), 1, 2.5, or 5 mg/kg/day cholecalciferol (Sigma, USA) from PD 2–30; therefore receiving cholecalciferol before, during, and after ethanol exposure [19]. Peak blood alcohol concentrations (BAC) were measured on PD 6 (20 µ L blood samples; Analox Ethanol Analyzer, Model AM1; Lunenberg, MA), 1.5 hrs after the second ethanol intubation [20]. 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 levels were analyzed from dried blood spots by ZRT Laboratory (OR); tail vein blood samples (100 µ L) were taken on PD 6 (during ethanol exposure and cholecalciferol treatment) and PD 16 (during cholecalciferol treatment). On PD 49–52, subjects were tested on a serial spatial discrimination reversal learning task, which required the subject to escape from one goal arm of a T-maze (19 cm wide passages, 71 cm long stem, 91 cm arm span, 10 cm wide culde-sac at each end) partially submerged in a tank (121 diameter) of 26°C water made opaque with powdered milk [21, 22]. Subjects were initially trained to escape from each goal arm, trained with only one goal arm available at a time (1 day; 10 trials; inter-trial interval 1–2 mins). During testing (3 days; 30 trials/day; inter-trial interval 1–2 mins), both goal arms were open, but only one contained an escape ladder. Entries into the incorrect arm, back into the starting stem, or into the correct arm without escaping, constituted errors. Thus, a subject could commit multiple errors before escaping. Once the subject achieved 6 trials with no errors (success criterion), the contingencies were reversed and the subject could only escape from the previously non-reinforced arm. Testing to that arm continued until a success criterion was achieved. Thus, each time the subject reached success criterion, the location of the escape ladder was switched. Number of trials to the first success criterion, total number of successful discriminations achieved, and number of errors (initial and perseverative) served as performance measures.

3. Results

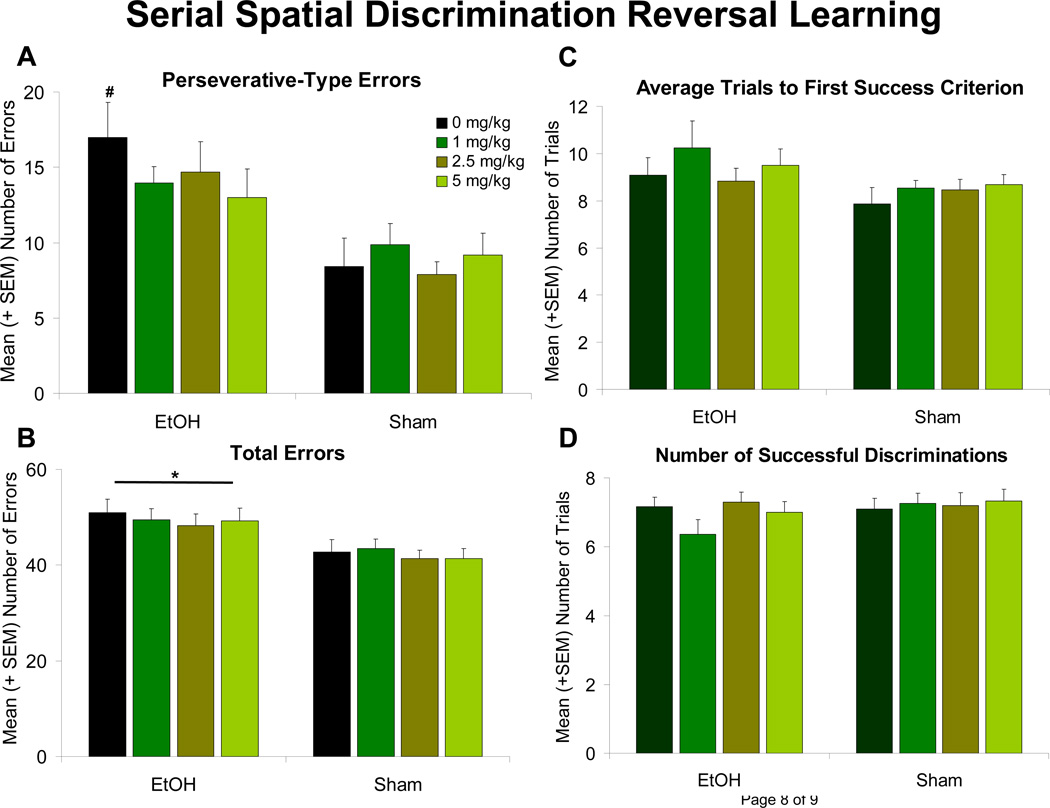

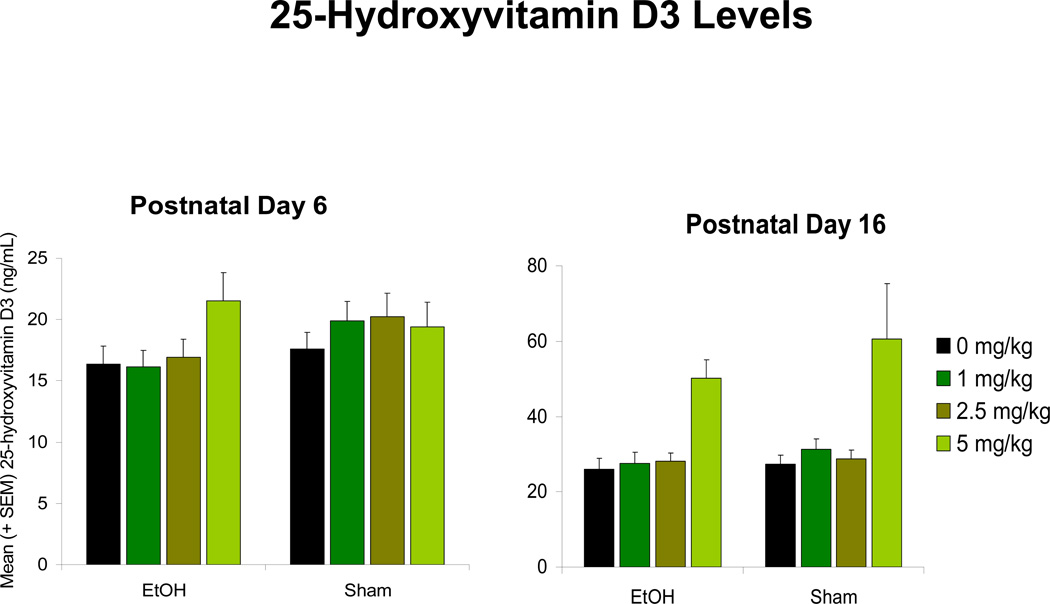

Subjects exposed to ethanol during development committed significantly more errors in the spatial discrimination reversal learning task [F(1,139) = 20.9, p < 0.001] when compared to the sham controls (Figure 1B). This effect was primarily driven by the number of perseverative-type errors (multiple errors made within a trial), as no significant EtOH nor Cholecalciferol effect was observed on the number of trials with errors (all p’s > 0.05) (results not shown). Ethanol-exposed subjects performed significantly more perseverative-type errors [F(1,139) = 26.3, p < 0.001] (Figure 1A). Although the EtOH x Cholecalciferol interaction failed to reach significance (p > 0.05), a priori comparisons among EtOH groups illustrated 5 mg/kg/day cholecalciferol significantly attenuated the number of ethanol-related perseverative-type errors, differing significantly from the EtOH group that received 0 mg/kg/day cholecalciferol. Administration of 1 and 2.5 mg/kg/day cholecalciferol did not significantly mitigate ethanol-induced increases in perseverative-type errors. No significant effect of EtOH or Cholecalciferol was found in the number of trials to the first success criterion or in the total number of successful discriminations achieved (all p’s > 0.05; Figure 1C and D). Although results remain preliminary, Cholecalciferol did not have a significant effect on peak BAC levels (PD 6) (p > 0.05), and ethanol exposure did not show any significant effects on circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 levels on any of the days investigated (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Serial Spatial Discrimination Reversal Learning.

Left: Errors. Ethanol-exposed (EtOH) subjects made significantly more errors (A), specifically perseverative-type errors (B), than Sham animals. Administration of 5 mg/kg cholecalciferol significantly reduced the number of perseverative-type errors.

* = significantly different from all Sham groups

# = significantly different from all Sham groups and EtOH + 5 mg/kg

Right: Successes. No significant effect of Ethanol or Cholecalciferol was found in the number of trials to the first success criterion (C) or in the total number of successful discriminations achieved (D) (all p’s > 0.05).

Figure 2. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D3 Levels.

Ethanol (EtOH) exposure did not significantly affect circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 levels at any given dose level, when investigated during ethanol exposure (postnatal day 6) or cholecalciferol treatment (postnatal day 16).

4. Discussion

This study is the first to our knowledge to explore cholecalciferol as a potential therapeutic for behavioral deficits associated with FASD. Ethanol-exposed subjects were not impaired in their ability to discriminate spatial location (e.g. number of trials to first success criterion), but they did have more perseveration across trials, exhibiting a lack of behavioral flexibility. This finding is consistent with previous studies [21, 22] and reflects both human and animal FASD reports on response inhibition deficits, possibly related to hippocampal [23] and/or prefrontal cortex [24] dysfunction. Cholecalciferol reduced the severity of ethanol-related perseverative behavior in a dose-dependent manner, with administration of 5 mg/kg/day cholecalciferol, but not 1 or 2.5 mg/kg, attenuating the ethanol-induced increases in perseverative-type errors. As no ethanol-induced decreases in 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 were observed, it would suggest that cholecalciferol was not compensating for a deficiency. Rather, we postulate that cholecalciferol’s neuroactive properties are intervening to, for example, increase neurotrophin levels that are otherwise down-regulated following developmental alcohol exposure [4, 5, 15, 25, 26]. Cholecalciferol may therefore also provide neuroprotection from ethanol-induced cell death in CNS regions such as the hippocampus [27], regions which are influenced by 1,25-hydroxyvitamin D3 levels [28] and also contain vitamin D receptors [29]. Importantly, the effects of cholecalciferol on ethanol-exposed subjects was observed after cholecalciferol treatment had ceased, suggesting that functional effects may continue beyond acute exposure. In sum, cholecalciferol supplementation could serve as a potential treatment and/or intervention for FASD.

Highlights.

Subjects exposed to ethanol during development exhibited learning deficits; Cholecalciferol attenuated ethanol-induced increases in perseverative errors; Vitamin D3 supplementation could serve as a potential treatment for FASD.

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff of the Center for Behavioral Teratology for facilitating these studies, particularly the technical expertise of Vanessa Wiley, Kristen Breit, Kyle Moranton, and guidance from Edward Riley. Funding for this work was provided by the ABMRF/The Foundation for Alcohol Research to NMI and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (AA12446) to JDT. All procedures included in this study were approved by the SDSU IACUC and are in accordance with the NIH Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Abbreviations

- CNS

central nervous system

- FASD

fetal alcohol spectrum disorders

- PD

postnatal day

- BAC

blood alcohol concentration

- EtOH

ethanol

- GDNF

glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor

- NT

neurotrophin

- NGF

nerve growth factor

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sampson PD, et al. Incidence of fetal alcohol syndrome and prevalence of alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorder. Teratology. 1997;56(5):317–326. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9926(199711)56:5<317::AID-TERA5>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sokol RJ, Delaney-Black V, Nordstrom B. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Jama. 2003;290(22):2996–2999. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.22.2996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.May PA, Gossage JP. Estimating the prevalence of fetal alcohol syndrome. A summary. Alcohol Res Health. 2001;25(3):159–167. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buell JS, Dawson-Hughes B. Vitamin D and neurocognitive dysfunction: preventing "D"ecline? Mol Aspects Med. 2008;29(6):415–422. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCann JC, Ames BN. Is there convincing biological or behavioral evidence linking vitamin D deficiency to brain dysfunction? Faseb J. 2008;22(4):982–1001. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-9326rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manari AP, Preedy VR, Peters TJ. Nutritional intake of hazardous drinkers and dependent alcoholics in the UK. Addict Biol. 2003;8(2):201–210. doi: 10.1080/1355621031000117437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Santori C, et al. Skeletal turnover, bone mineral density, and fractures in male chronic abusers of alcohol. J Endocrinol Invest. 2008;31(4):321–326. doi: 10.1007/BF03346365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hollis BW. Vitamin D requirement during pregnancy and lactation. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22(Suppl 2):V39–V44. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.07s215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keiver K, Herbert L, Weinberg J. Effect of maternal ethanol consumption on maternal and fetal calcium metabolism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996;20(7):1305–1312. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Milne M, Baran DT. Inhibitory effect of maternal alcohol ingestion on rat pup hepatic 25-hydroxyvitamin D production. Pediatr Res. 1985;19(1):102–104. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198501000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eyles D, et al. Vitamin D3 and brain development. Neuroscience. 2003;118(3):641–653. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00040-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eyles DW, et al. Developmental vitamin D deficiency causes abnormal brain development. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34(Suppl 1):S247–S257. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilson SE, Cudd TA. Focus On: The Use of Animal Models for the Study of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders. Alcohol Res Health. 2011;34(1):92–98. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Y, et al. Vitamin D(3) attenuates cortical infarction induced by middle cerebral arterial ligation in rats. Neuropharmacology. 2000;39(5):873–880. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00255-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kang H, Schuman EM. Long-lasting neurotrophin-induced enhancement of synaptic transmission in the adult hippocampus. Science. 1995;267(5204):1658–1662. doi: 10.1126/science.7886457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dobbing J, Smart JL. Vulnerability of developing brain and behaviour. Br Med Bull. 1974;30(2):164–168. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a071188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Livy DJ, et al. Fetal alcohol exposure and temporal vulnerability: effects of binge-like alcohol exposure on the developing rat hippocampus. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2003;25(4):447–458. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(03)00030-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Light KE, et al. Intragastric intubation: important aspects of the model for administration of ethanol to rat pups during the postnatal period. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22(7):1600–1606. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb03954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Csaba G, Kovacs P, Pallinger E. Impact of neonatal imprinting with vitamin A or D on the hormone content of rat immune cells. Cell Biochem Funct. 2007;25(6):717–721. doi: 10.1002/cbf.1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelly SJ, Bonthius DJ, West JR. Developmental changes in alcohol pharmacokinetics in rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1987;11(3):281–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1987.tb01308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Idrus NM, et al. The effects of a single memantine treatment on behavioral alterations associated with binge alcohol exposure in neonatal rats. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2011;33(4):444–450. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomas JD, et al. Choline supplementation following third-trimester-equivalent alcohol exposure attenuates behavioral alterations in rats. Behav Neurosci. 2007;121(1):120–130. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.121.1.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bardgett ME, et al. The effects of clozapine on delayed spatial alternation deficits in rats with hippocampal damage. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2006;85(1):86–94. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Riley EP, et al. The effects of physostigmine on open-field behavior in rats exposed to alcohol prenatally. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1986;10(1):50–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1986.tb05613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barclay DC, et al. Reversal of ethanol toxicity in embryonic neurons with growth factors and estrogen. Brain Res Bull. 2005;67(6):459–465. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2005.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Climent E, et al. Ethanol exposure enhances cell death in the developing cerebral cortex: role of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and its signaling pathways. J Neurosci Res. 2002;68(2):213–225. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonthius DJ, West JR. Alcohol-induced neuronal loss in developing rats: increased brain damage with binge exposure. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1990;14(1):107–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1990.tb00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prufer K, et al. Distribution of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 receptor immunoreactivity in the rat brain and spinal cord. J Chem Neuroanat. 1999;16(2):135–145. doi: 10.1016/s0891-0618(99)00002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Langub MC, et al. Evidence of functional vitamin D receptors in rat hippocampus. Neuroscience. 2001;104(1):49–56. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00049-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]