Abstract

Misfolding and aggregation of the amyloid β-protein (Aβ) are hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease. Both processes are dependent on the environmental conditions, including the presence of divalent cations, such as Cu2+. Cu2+ cations regulate early stages of Aβ aggregation, but the molecular mechanism of Cu2+ regulation is unknown. In this study we applied single molecule AFM force spectroscopy to elucidate the role of Cu2+ cations on interpeptide interactions. By immobilizing one of two interacting Aβ42 molecules on a mica surface and tethering the counterpart molecule onto the tip, we were able to probe the interpeptide interactions in the presence and absence of Cu2+ cations at pH 7.4, 6.8, 6.0, 5.0, and 4.0. The results show that the presence of Cu2+ cations change the pattern of Aβ interactions for pH values between pH 7.4 and pH 5.0. Under these conditions, Cu2+ cations induce Aβ42 peptide structural changes resulting in N–termini interactions within the dimers. Cu2+ cations also stabilize the dimers. No effects of Cu2+ cations on Aβ–Aβ interactions were observed at pH 4.0, suggesting that peptide protonation changes the peptide-cation interaction. The effect of Cu2+ cations on later stages of Aβ aggregation was studied by AFM topographic images. The results demonstrate that substoichiometric Cu2+ cations accelerate the formation of fibrils at pH 7.4 and 5.0, whereas no effect of Cu2+ cations was observed at pH 4.0. Taken together, the combined AFM force spectroscopy and imaging analyses demonstrate that Cu2+ cations promote both the initial and the elongation stages of Aβ aggregation, but protein protonation diminishes the effect of Cu2+.

Keywords: Amyloid β-protein, Aβ42, Alzheimer’s disease, Cu2+ cations, Single molecule force spectroscopy, Atomic force microscopy imaging

Introduction

Misfolding and aggregation of the amyloid β–protein (Aβ) peptide are two of the key features of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (Dobson 2003), which has no cure at the present time. Aβ peptide, including residues 39–43, is capable of forming aggregates of various morphologies, including fibrils (Bitan et al. 2003; Ono et al. 2009). Several lines of evidence suggest that Cu2+ cations play an important role in the aggregation of Aβ42 both in vitro and in vivo. For example, a prominent characteristic of AD is altered Cu2+ concentrations in the brain and disrupted Cu2+ homeostasis (Roberts et al. 2012). Cu2+ ions are found concentrated within senile plaques of AD patients directly bound to Aβ with a picomolar affinity (Hong and Simon 2011). The concentration of Cu2+ within the senile plaques of AD patients is 26 times higher than within the extracellular space of healthy individuals (Chen et al. 2011). Aβ plaques are therefore considered a metal “sink” (Atwood et al. 1998). Copper in a high-cholesterol diet induces amyloid plaque formation and learning deficits in a rabbit model of AD (Sparks and Schreurs 2003). Trace amounts of metal cations initiate and promote Aβ aggregation (Huang et al. 2004; Innocenti et al. 2010). Moreover, metal cations are believed to contribute to AD pathogenesis by causing oxidative stress, which could lead to the dysfunction or death of neuronal cells (Jomova et al. 2010; Barnham et al. 2004). One of the prevailing underlying mechanisms of AD etiology is the metal–triggering hypothesis (Hung et al. 2010; Rivera-Mancia et al. 2010).

Although a few papers report inhibitory effects of Cu2+ cations on Aβ aggregation (Zou et al. 2001), it is generally accepted that Cu2+ cations promote Aβ aggregation (Faller 2009; Lin et al. 2010). However, the end products of Aβ aggregation in the presence of Cu2+ cations remain unclear. Whether Cu2+ cations accelerate the growth of Aβ42 fibrils has been vigorously debated in recent years. The published results have been confusing and, to some extent, contradictory. Both amorphous aggregates and fibrils were reported to be end products (Miura et al. 2000; Tougu et al. 2011), indicating the complexity of the Cu2+–Aβ interaction. It is now understood that the Cu2+–Aβ interaction is sensitive to experimental conditions (Olubiyi and Strodel 2012; Klug et al. 2003), such as pH, Aβ concentration, ionic strength, temperature, and agitation. A minor change in experimental conditions may lead to different morphologies of Aβ aggregates. The effect of metal cations on Aβ aggregation is also metal/sequence-specific (Dong et al. 2007). Copper cations accelerated fibril formation of Aβ (14–23), but inhibited formation of Aβ (11–23) and Aβ (11–28) (Faller and Brown 2009).

Despite the fact that the effects of Cu2+ cations on Aβ aggregation have been extensively investigated, the underlying mechanism controlling aggregation remains elusive. One of the main challenges is obtaining detailed Cu2+–Aβ42 interaction information during the earliest stage of aggregation, especially in the dimerization phase, because oligomers are transient states not amenable to traditional visualization techniques. In addition, the ability of Cu2+ cations to promote the growth of fibrils needs to be verified. Therefore, a thorough study capable of probing transient states of Cu2+–Aβ42 interactions at the single molecule level would be significant.

Recently, the single molecule force spectroscopy (SMFS) mode of atomic force microscopy (AFM) has been used to detect the specific interaction forces of biological molecules (Krasnoslobodtsev et al. 2007; Sulchek et al. 2005). We recently succeeded in using SMFS to characterize the early stage of Aβ and α–synuclein aggregation (Kim et al. 2011; Yu et al. 2011). These studies revealed the high stability of Aβ and α–synuclein misfolded dimers and led to a novel hypothesis explaining the role of dimerization in amyloid protein misfolding and aggregation (Lyubchenko et al. 2010). Furthermore, by using SMFS, we examined the effects of Zn2+ and Al3+ on the early stages of α–synuclein aggregation at neutral pH (Yu et al. 2011). The results demonstrated that Zn2+ and Al3+ greatly promote the dimerization of α–synuclein. It is thus reasonable to extend the use of AFM to inspect the effect of Cu2+ cations on Aβ42 aggregation. The application of AFM and SMFS can provide direct information about Aβ aggregation at the nanometer level.

In this paper, we report on data from our SMFS and AFM imaging studies to elucidate the effect of Cu2+ cations on interactions of Aβ42 peptides during the initial stages of aggregation and on the growth of aggregates at later stages. The role of pH on Cu2+–Aβ42 interactions is also discussed. We find that Cu2+ cations change the interaction pattern of Aβ42 dimers and accelerate the aggregation process by promoting fibrillogenesis, but these effects are abolished in acidic conditions. These results may have relevance for understanding the etiology of AD and for development of knowledge-based drug design strategies targeting metal − Aβ interactions.

Materials and methods

Materials

Aβ42 (CDAEFRHDSGYEVHHQKLVFFAEDVGSNKGAIIGLMVGGVVIA) was synthesized using 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl (Fmoc) chemistry and purified by reverse phase high performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC). The identity and purity (usually >97%) of the peptides were confirmed by amino acid analysis followed by mass spectrometry and reverse phase high performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC). The lyophilized Aβ42 was dissolved in TFA (2 mg/ml) by ultrasonication (Branson 1210) for 5 min to destroy dimeric and higher oligomers and then dried immediately using a vacuum centrifuge (Vacufuge, Eppendorf). The white powder of Aβ42 was dissolved at 2 mg/ml in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) as a stock solution and then diluted in DMSO before being used. The final concentration of diluted Aβ42 was determined by spectrophotometry (Nanodrop® ND–1000). The molar extension coefficients used for tyrosine and cysteine were 1280 cm−1·m−1 and 120 cm−1·m−1, respectively. Stock solutions of cysteinyl-Aβ42 were prepared as previously described (Kim et al. 2011; Yu et al. 2008; Walsh et al. 1997).

A 50 mM 1–(3–aminopropyl) silatrane (APS) stock solution was prepared by dissolving the APS powder in DI water. The 1.67 mM stock solution of maleimide–polyethylene glycol–succinimidyl valerate (MAL–PEG–SVA; 3.4 kDa Laysan Bio Inc, Arab, AL) was prepared in DMSO (Sigma–Aldrich Inc.) and stored at −20°C. The 10 mM Tris (2–carboxyethyl) phosphine (TCEP) hydrochloride (Hampton Research Inc.) and the 2.94 mM stock solution of maleimide silatrane (MAS) were prepared in DI water and stored at −20°C. A 20 mM stock solution of β–mercaptoethanol was prepared in pH 7.4 buffer and kept under room temperature.

Copper chloride (CuCl2) was purchased from Sigma–Aldrich and used without additional purification. A 1 mM stock solution of CuCl2 was prepared by dissolving the CuCl2 powder into DI water. Glycine was added into the buffer solutions at pH 7.4 and 6.0 to stabilize the CuCl2 stock solution. The CuCl2 solutions with different pH values were all diluted to a final concentration of approximately 1–5 μM. Other reagents used in the experiments were of analytical grade from Sigma–Aldrich, unless otherwise specified. Deionized water (18.2 MΩ, 0.22 μm pore size filter, APS Water Services Corp., Van Nuys, CA) was used for all experiments.

Buffer solutions

Buffers were 50 mM 4–(2–hydroxyethyl)–1–piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) (pH 7.4), 20 mM 3–(N–morpholino) propanesulfonic acid (MOPS) (pH 6.8), 20 mM monopotassium phosphate (pH 6.0), and 10 mM sodium acetate (pH 5.0 and 4.0). All buffer solutions were adjusted to a final ionic strength of 150 mM using sodium chloride and were filtered through 0.22 μm disposable nylon filters before use.

Functionalization of AFM tips

The functionalization of AFM tips and mica surfaces were done as described previously (Yu et al. 2008; Yu and Lyubchenko 2009). Briefly, silicon nitride (Si3N4) AFM tips (MSNL–10, Veeco) were immersed in 100% ethanol solution for 15 min, rinsed thoroughly with water, dried with argon, and then exposed to UV light (CL–1000 Ultraviolet Crosslinker, UVP, Upland, CA) for 30 min. The AFM tips were placed in an aqueous solution of 167 μM MAS for 3 h followed by multiple thorough rinses with water. A 20 nM Aβ42 peptide solution in pH 7.4 HEPES buffer solution was pretreated with 20 μM TCEP hydrochloride for 15 min to break any intermolecular disulfide bonds between the Aβ42 molecules and ensure that the covalently attached Aβ42 molecules were in monomeric form. The MAS–modified AFM tips were immersed into the above mentioned peptide solution for 1 h to covalently attach the peptides. After rinsing with pH 7.4 HEPES buffer, the Aβ42 peptide–tethered AFM tips were treated with 10 mM β–mercaptoethanol solution for 10 min to block the unreacted maleimide moieties. Finally, the Aβ42 peptide–functionalized AFM tips were washed with pH 7.4 HEPES and stored in the same buffer. Typically, the storage time was less than 24 h.

Modification of mica surfaces

Mica sheets (Asheville–Schoonmaker Mica Co., Newport News, VA) were cut into 1.5 cm × 1.5 cm squares. The freshly cleaved mica surfaces were treated with APS for 30 min followed by reaction with 167 μM MAL–PEG–SVA in DMSO. After activation for 3 h, the mica squares were rinsed sequentially with DMSO and water to remove unbound MAL–PEG–SVA, and then dried with argon. The remaining steps for immobilizing the Aβ42 peptides onto the mica surface were the same as described above for the AFM tips.

Single molecule force spectroscopy

The single molecule force spectroscopy force measurements were conducted in different pH buffer solutions at room temperature with the Molecular Force Probe 3D AFM system (MFP 3D, Asylum Research, Santa Barbara, CA). AFM probes with nominal spring constants of 0.03 N/m were used throughout the experiments. The apparent spring constants were calibrated by the thermal noise analysis method with the Igor Pro 6.04 software (provided by the manufacturer). A low trigger force (100 pN) was exerted on the AFM probes. The retraction velocity of all experiments was set at 500 nm/s. At each pH, force measurements between Aβ42–functionalized AFM tips and Aβ42–modified mica were first performed in the absence of Cu2+ and then in the presence of Cu2+. The tip and mica remained intact in the presence of Cu2+. For each force measurement, at least 100 rupture events were collected over at least three randomly chosen locations on the mica surface to allow accurate statistical analysis. Force curves were obtained by probing over area 5×5 μm generating force maps each sized in 60 × 40 points. It took 35~75 min to finish a single force map; the time depends on the retraction velocity. The sampling rate for each force curve varied from 1 kHz to 2 kHz. By using the exact same experimental setup, the same concentration of Aβ42, and the same type of AFM tips throughout all experiments, several attempts of force probing were made for each experiment. Therefore, it was reasonable to calculate the yield of rupture events by averaging the numbers of yield obtained from a set of repeating experiments.

Tapping mode AFM imaging

The growth of Aβ fibrils in the absence and presence of Cu2+ was monitored with tapping mode AFM (Nanoscope V, Veeco). Aβ stock solutions were diluted with a working buffer solution and filtered through a 10 kDa filter unit (Amicon® Ultra) by centrifuging at 16,873 × g for 15 min. The final Aβ concentration was 10 μM for all imaging experiments. Substoichiometric Cu2+ cations were added in Aβ solutions at a molar ratio of 1:10. Cu2+ free Aβ solutions also were prepared in parallel as control experiments. All Aβ solutions were incubated at 37°C under quiescent conditions. Samples for AFM imaging were prepared every day to check the progress of aggregation. After each sample preparation, 4 μL of the incubated solution was deposited on a freshly cleaved bare mica surface, which was immobilized on a metal disc via a double–sided sticker. The solution was allowed to sit for 2 min to let the Aβ aggregates absorb onto the mica surface. The mica surface was rinsed with DI water to remove any soluble solvents. The mica surface was then dried with argon and placed into a vacuum chamber for at least 3 h, after which imaging was performed. Images with typical features (5×5 μm in size) were acquired at a scan rate of 1 Hz and resolution of 512×512.

Data analysis

Three rules were applied to select force–distance curves: 1) according to the thermal noise of the experimental setup, the rupture forces should be higher than 20 pN; 2) the contour lengths (the length at maximum physically possible extension of the interaction system determined after the WLC analysis) should be larger than 20 nm (see Results below); 3) the distance of the tip-sample separation (the projection of distance between AFM tip and mica substrate on the vertical axis) should be larger than 15 nm to exclude the nonspecific interactions between the tip and bare mica. All force curves which did not meet the above requirements were discarded. Overlapping of raw rupture forces was accomplished by using Igor Pro software.

The worm like chain (WLC) model was used for fitting the force-distance curves:

| (1) |

where F(x) is the force at the distance of x, kB is the Boltzman constant, T is the absolute temperature, and Lp and Lc are the persistence length and the contour length, respectively. The persistence length of PEG was fixed at 0.38 nm (Gomez-Casado et al. 2011). From the WLC fit of force distance curves, the contour lengths were obtained with the Igor Pro 6.04 software package.

The apparent loading rates were calculated by using the following equation (Yu et al. 2011):

| (2) |

where Fp= kBT/Lp, kc is the spring constant (pN/nm), v is the tip velocity, F is the rupture force, and r is the apparent loading rate (pN/s). All histograms were generated by Origin 7.0 software and fitted with a Gaussian distribution. Data are shown in the form of mean ± SD.

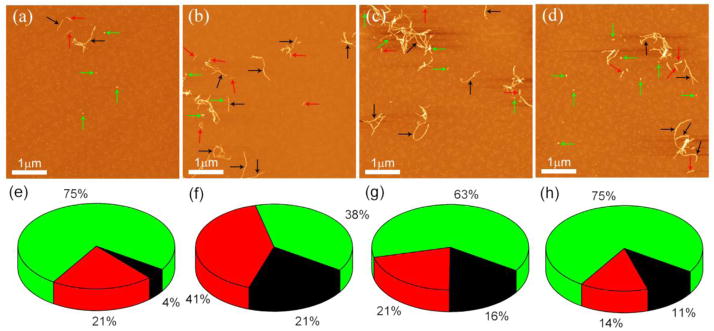

Quantitative analysis of Aβ aggregates was achieved by using Femtoscan Online software (Advanced Technologies Center, Moscow, Russia) (Portillo et al. 2012). The background was initially subtracted to eliminate anything that was less than 1 nm in height. The “enum features” function was used to count the particle number and read out information about shape and height. This function can be used to determine the elongation factor of the Aβ aggregates, which is represented as Rs/Rp (the ratio between two radii in an oblong object), also known as form factor. Form factors were interpreted as follows: 0–0.5 represented mature fibrils; 0.5–0.8 represented protofibrils; and 0.8–1.0 represented oligomers. The percentages of various Aβ aggregates were calculated and shown as pie charts.

Results

Experimental setup of SMFS

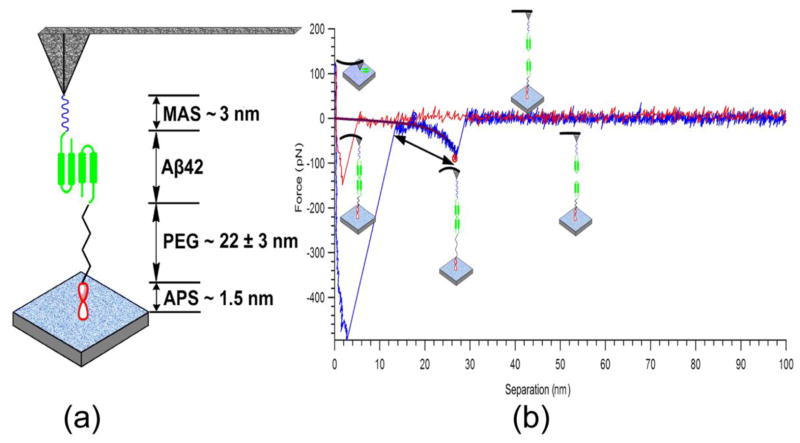

It is a widely acknowledged fact that Aβ aggregation must begin with peptide dimerization. Therefore, we rationalized that immobilization of Aβ42 monomers on the tip and the mica surface would represent a pivotal step in order to analyze the initial stages of aggregation. Our experimental setup is illustrated in Fig. 1a. One of the interacting Aβ42 molecules is anchored onto the AFM tip through a short linker, MAS, and a second Aβ42 molecule is immobilized on the mica surface using a long PEG linker. Specific interaction forces between these molecules were measured by multiple approach-retraction cycles. Treating the Aβ42 solution with TCEP efficiently reduces cystine links that create Aβ dimers (Kim et al. 2011). Therefore, the Aβ42 molecules used for immobilization were single monomers. In addition, we took advantage of the presence of the maleimide group exclusively covalently coupled to the cysteine group at the N–terminus of Aβ42. The concentration of Aβ42 peptide used in the current study was as low as 20 nM, therefore this site-specific attachment would result in sparse surface presentation of Aβ42 molecules onto the mica surface and AFM tip, preventing peptide aggregation during the immobilization step (Yu et al. 2011; Kim et al. 2011). Additionally, the concentration of Aβ42 peptide used was more than three orders of magnitude less than that used in aggregation experiments in vitro (Kim et al. 2011; Yu et al. 2011). Bifunctional PEG was chosen to circumvent unwanted nonspecific interactions between the AFM tip and the mica surface, and to function as a spacer to sort out the nonspecific interactions that often take place between tips and substrates with a short separation.

Figure 1.

Experimental setup of SMFS (a). One of the interacting Aβ42 molecules is immobilized on the APS modified mica surface via a long PEG linker. The counterpart Aβ42 molecule is anchored on the MAS functionalized AFM tip. A typical approach–retraction cycle of recorded rupture force curve (b). The rupture events and the polymer stretching segment of the force curve are indicated with a single-headed arrow and a double headed arrow, respectively.

Fig. 1b shows a typical rupture force–distance curve with a clear peak located at a distance defined primarily by linker stretching that could be associated with the specific interactions between Aβ42 molecules. Prior to this rupture peak, a section of a parabolic curve exists that originates from stretching of the extendable segments of the linkers and the interacting molecules.

Effect of Cu2+ cations on the Aβ42 interaction

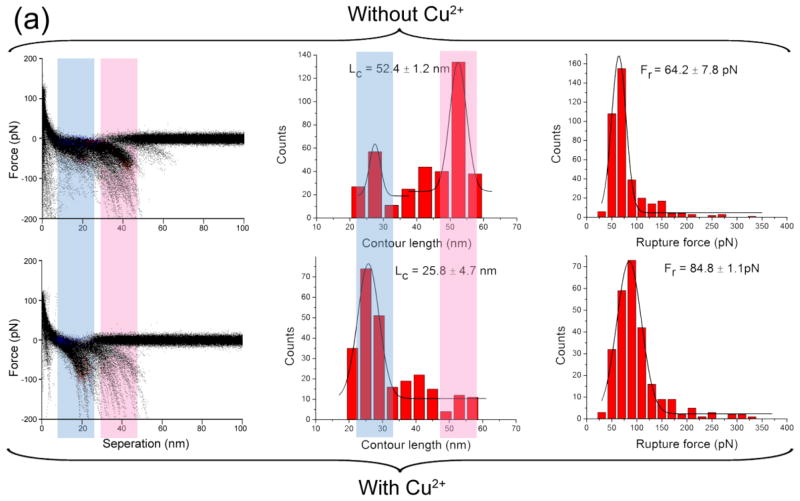

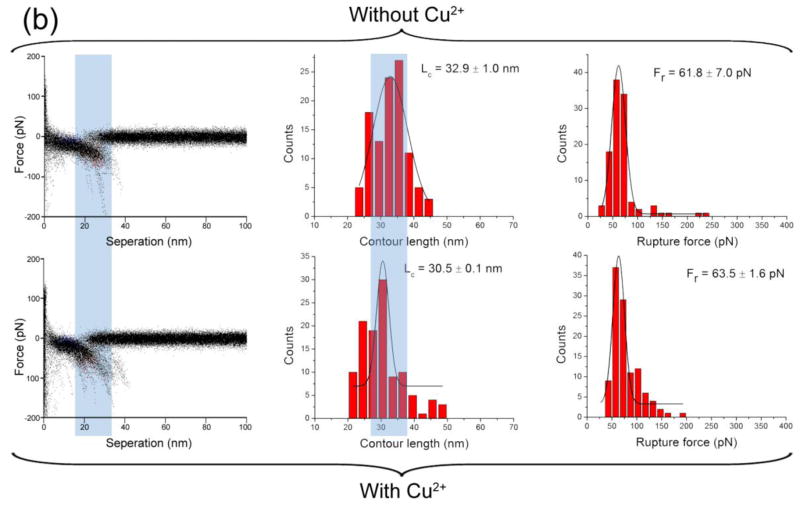

The effect of Cu2+ cations on the Aβ42 interaction was investigated by SMFS at pH values of 7.4, 6.8, 6.0, 5.0 and 4.0. An overlap of all raw force curves obtained in the absence and presence of Cu2+ cations and at the physiological condition, pH 7.4, is shown in the left column of Fig. 2. Clustered data points at certain rupture lengths and rupture forces represent visual presentations of the overlay of multiple rupture events and provide a clear comparison between the presence and absence of Cu2+ cations. Major differences between these two types of experiments are highlighted with colored light pink or light blue vertical bands.

Figure 2.

AFM force spectroscopy in the presence and absence of Cu2+ cations at pH 7.4. The force spectroscopy in the absence of Cu2+ cations is shown in the upper panel. The columns include, from left to right: the overlap of all raw force curves, the distribution of contour length, and the distribution of rupture force. The lower panel shows the corresponding characteristic of force spectroscopy in the presence of Cu2+ cations. The Lc and Fr denote the most probable contour length and the most probable rupture force, respectively.

In the absence of Cu2+ cations, the most probable contour length was 53.6 ± 9.7 nm (Fig 2; middle column). This value includes the length of the flexible tethers used for the peptide immobilization and the length of the stretchable segment of the peptide between the N–terminus and the peptide segment involved in the dimer stabilization (Yu et al. 2011; Yu et al. 2008; Lyubchenko et al. 2010; Kim et al. 2011). According to Fig. 1a, the total length of the tethers is 26.5 ± 3.0 nm (Supplementary material); therefore we estimate the contour length of the stretchable segment of Aβ42 molecule at these conditions to be 13.6 ± 5.1 nm per Aβ42 molecule. Given the length of each amino acid as 0.34–0.4 nm, we estimate that more than a half of the N-terminus of the peptide is unstructured and undergoes stretching. In the presence of Cu2+ cations, the most probable contour length decreased to 31.6 ± 3.5 nm, which corresponds to a stretchable segment length of 2.6 ± 2.3 nm, or 5–7 aa (amino acids) per Aβ42 molecule. This suggests that Cu2+ cations alter the folding pattern of Aβ42 dimers resulting in the inclusion of the entire N-terminus. This structural change is accompanied by a 15% increase in rupture forces.

The central motivation of this work was to investigate the effect of Cu2+ cations on the early stages of Aβ aggregation. Careful comparison of force results has been made between Cu2+–present and Cu2+–free experiments. In the absence of Cu2+, the N terminus (D1 K16) as well as the central hydrophobic cluster (L17–A21) of Aβ42 peptides were found not to be involved in interpeptide interactions. By contrast, these two parts were brought to form Aβ dimer complexes by Cu2+. This finding was in line with a recent study, in which the N terminus of Aβ was observed to participate the formation of β–sheet conformation (Haupt et al. 2012).

The shift in the contour length values induced by Cu2+ cations also was observed at pH 5.0 (Fig. 3a), with a 40% increase in the rupture force. A similar pattern was observed at pH 6.8 (Supplementary Fig. S1) and pH 6.0 (Supplementary Fig. S2). Additionally, for pH values from 7.4 to 5.0, the statistical average yields of rupture events in the presence of Cu2+ cations were at least two times higher than those in the Cu2+–free experiments, suggesting that Cu2+ cations promote the dimerization of Aβ42. Experiments performed at pH 4.0 (Fig. 3b) demonstrate that Cu2+ cations have minimal effects on Aβ2 interactions under these conditions. Thus, Cu2+ cations promote the dimerization of Aβ42 over the pH range of 7.4–5.0, but this effect is not observed at more acidic pH. This finding is consistent with the results obtained by other methods that demonstrated that Cu2+ cations did not interact with Aβ when the pH was below 5.0 (Atwood et al. 1998).

Figure 3.

AFM force spectroscopy in the presence and absence of Cu2+ cations at pH 5.0 is shown in (a). The force spectroscopy in the absence of Cu2+ cations is shown in the upper panel. The columns include, from left to right: the overlap of all raw force curves, the distribution of contour length, and the distribution of rupture force. The lower panel shows the corresponding characteristic of force spectroscopy in the presence of Cu2+ cations. Similar SMFS results in the presence and absence of Cu2+ cations at pH 4.0 are shown in (b). The Lc and Fr denote the most probable contour length and the most probable rupture force, respectively.

Effect of Cu2+ cations on Aβ42 aggregation

We used AFM imaging to directly inspect the effect of Cu2+ cations on Aβ aggregation at later stages. We incubated 10 μM Aβ solutions under quiescent conditions at all pH values studied above and imaged aliquots taken at various times during the aggregation process.

At pH 7.4, long fibrils with heights of 4.6 nm appeared on the 6th day in the presence of substoichiometric Cu2+ cations (Fig 4a, black arrows). Shorter and thinner fibrils were also observed (profibrils), as indicated with red arrows. These fibrillar features were found in the absence of Cu2+ cations (Fig. 4b). Bright globular features (oligomers) were observed, as indicated with green arrows. A corresponding quantitative analysis of Aβ aggregates is shown in Fig. 4c. A large proportion of fibrils were observed by AFM in the presence of Cu2+ cations, suggesting that Cu2+ cations promote Aβ aggregation in the elongation phase. At pH 5.0, Aβ fibrils appeared in experiments with and without Cu2+ cations (Fig. 5a and 5b). However, the percentage of fibrils in the presence of Cu2+ cations was significantly larger (21%) than that in the control experiment (4%), as shown in Fig 5f and 5e. Fibrils were observed both in the absence and presence of Cu2+ cations after 5 days of incubation at pH 4.0 (Fig 5c and 5d). These results are consistent with our force spectroscopy data that demonstrated no effects of Cu2+ under these conditions. The fibril populations in both experiments were similar (Fig 5g and 5h), even though images were acquired at arbitrarily chosen spots that may have different surface coverage. In the present study, a long lag phase for fibril growth was found at pH 4.0 and 7.4; consistent with the notion that pH 5.0 is the optimum condition for A aggregation in contrast to pH 4.1 and pH 7.0–7.4 (Snyder et al. 1994).

Figure 4.

Representative AFM images of Aβ42 aggregates in the presence (a) and absence (b) of Cu2+ cations at pH 7.4. Yields of aggregates formed in the presence of Cu2+ cations (c) and absence of Cu2+ cations (d) are shown in pie charts. Mature fibrils, protofibrils and oligomers are colored in black, red, and green, respectively.

Figure 5.

(a) and (b) show representative AFM images of Aβ42 aggregates in the absence and presence of Cu2+ cations at pH 5.0, respectively. Representative AFM images of Aβ42 aggregates in the absence (c) and presence (d) of Cu2+ cations at pH 4.0. Yields of aggregates formed in the absence of Cu2+ cations (e) and presence of Cu2+ cations (f) are shown in pie charts. Mature fibrils, protofibrils and oligomers are colored in black, red, and green, respectively. (g) and (h) show the yields of aggregates formed in the absence of Cu2+ cations and presence of Cu2+ cations, respectively.

Discussion

Cu2+ cations change the structure of Aβ42 dimers

AFM force spectroscopy revealed that Cu2+ cations dramatically change the folding pattern of Aβ42 within dimers. In the absence of the cations, the monomers are stabilized by the interactions of peptide segments located at the C-terminus of the peptide. Assuming the dimers are symmetrically formed, the linker length analysis shows that in the absence of Cu2+ cations the N-terminal segment of the peptide up to Ser26 is not involved with interpeptide interactions. The addition of Cu2+ cations dramatically decreases the non-interacting regions, shortening the N-terminal region to Arg5–Asp7. The pattern is essentially similar in the pH range between pH 7.4 and pH 5.0. Additionally, in the presence of Cu2+ cations, dimer stability is increased, dependent on pH. At pH 7.4, the increment on rupture force is approximately 15%; however, at pH 5.0, the value increases by a factor of three. The finding that the peptide N–terminus is involved in dimer stabilization is consistent with early studies that have shown that three histidine residues at the N–terminus are the major Cu2+ coordination sites (Shin and Saxena 2008). Copper, in its oxidized form, Cu2+, causes the pKa value of the imidazole of the histidine residue to decrease from 14 to approximately 7. This change enables protonation of the imidazole and the coordination of Cu2+ cations over a broad pH range (Rauk 2009; Ali-Torres et al. 2011). In addition to the three histidine residues, Asp1 (Hong et al. 2010), Ala2 (Drew et al. 2009), Glu3 (Miura et al. 2004), Asp7 (Sarell et al. 2009), Tyr10 (Stellato et al. 2006), Glu11 (Streltsov et al. 2008), and Val40 (Parthasarathy et al. 2011) were also reported to be the coordination site. Therefore, a plausible explanation of the rupture observed with short contour lengths is that the coordination of Cu2+ to N–terminal residues leads to a conformational change of Aβ42 that significantly facilitates the intrapeptide contact.

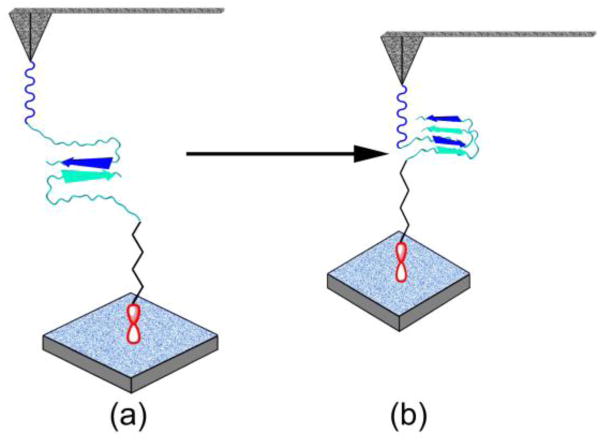

On the basis of these findings, we propose a model of Cu2+ cation mediated structural transitions of Aβ42 into misfolded states, as shown schematically in Fig. 6. In the absence of Cu2+ cations, the dimer is stabilized by the interactions of the Aβ42 C–termini, schematically shown by two arrows (Fig. 6a). With a strong rupture force these two segments can form antiparallel β-sheet structures. Shortening of the non-structured N-termini suggests that in the presence of Cu2+ cations, monomeric Aβ42 folds and these folded conformers interact with each other, as shown schematically in Fig. 6b. We assume that this conformation is close to the one found for Aβ42 structures in fibrils. The Glu11-Lys16 N-terminal region of this structurally different monomeric unit is involved in an intramolecular antiparallel β–sheet structure (Ahmed et al. 2010). This is in agreement with the contour length analysis that indicates the rupture position at Arg5–Asp7. Additionally, a β–turn exists at the Asp23–Lys28 region (Lazo et al. 2005; Ahmed et al. 2010). This model is consistent with a prevailing pathway for Cu2+ induced Aβ aggregation, in which Cu2+ cations induce a conformational change from mostly random coils through a partially helical conformation to a partially β–sheet structure (Yang et al. 2006). The circular dichroism experiments have demonstrated that intermediates with partial α–helix and β–sheet structures exist during the transition from monomers to fibrils before rapid aggregation (Kirkitadze et al. 2001; Fezoui and Teplow 2002). This conformational change is also supported by the solution studies of the Aβ peptide structure by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (Stroud et al. 2012), solution NMR spectroscopy (Olofsson et al. 2009), and mass spectroscopy (Murariu et al. 2007).

Figure 6.

Schematic view of the proposed structure model of Aβ42 dimer formation in the absence (a) and presence (b) of Cu2+ cations. The structure of Cu2+–free dimers is characterized by an interpeptide interaction between the two hydrophobic C–termini of the Aβ42 peptides. With Cu2+, the dimers adopt a compact structure highlighted by an interpeptide parallel β-sheet structure.

Other than the conformational change pathway, other possible pathways of Cu2+ cation induced Aβ aggregation include: 1) catalysis of dimer formation (via dityrosines) by radical chemistry (Murakami et al. 2005; Smith et al. 2007); 2) bridging of a histidine residue by two metal ions (Smith et al. 2006); and 3) change of overall net charge (Sarell et al. 2010; Syme et al. 2004). In our experiments, radical chemistry is not possible because we did not use reductants. Second, the likelihood of the bridging effect is low as the rupture forces in the presence of Cu2+ cations were less than 50 pN. With the level of force loading rates used in our force measurements, breaking an interpeptide metal coordination bond often generates moderate rupture forces (58 pN) (Beyer and Clausen-Schaumann 2005; Schmitt et al. 2000). Cu2+ cations may alter the net charge of Aβ42 because this peptide possesses a net charge of −3 under physiological conditions (Rauk 2009). Cu2+–induced charge neutralization could result in a strong propensity for peptide self-association. This could explain our force spectroscopy results at 7.4; however, this would not be consistent with our results obtained at mildly acidic pH in which the Aβ42 pI was 5.4, and the fact that stronger aggregation effects were observed at pH 5.0 than at pH 7.4. Another model suggests that Cu2+ cations change the positive charge density at the N-terminus of Aβ42. Enhanced charge density may conversely raise the proportion of β–structure (Klug et al. 2003; Rauk 2009). This notion is more practically consistent with the conformational change model than other models.

Substoichiometric concentrations of Cu2+ cations accelerate Aβ42 aggregation

In addition to the effect of Cu2+ cations on Aβ misfolding, Cu2+ changes the pattern of later stages of peptide aggregation by facilitating fibril formation at pH 7.4 that does not appear in the absence of Cu2+ cations. AFM imaging reveals fibrils in the absence of Cu2+ cations at pH 5.0 because aggregation is facilitated by acidic condition. However, in the presence of Cu2+ cations, the yield of fibrils is significantly higher than that in metal–free systems, suggesting that Cu2+ cations are still capable of promoting Aβ42 aggregation under these conditions (Fig. 5e and 5f). At pH 4.0, samples in the presence and absence of Cu2+ cations both show similar aggregation behavior, indicating that the aggregation effects of Cu2+ are lost. These findings, along with the force spectroscopy results, suggest that Cu2+ cations facilitate all stages of Aβ aggregation. The appearance of fibrils in the presence of Cu2+ cations may require both dilute concentrations (not higher than 10 μM) and substoichiometric amounts of Cu2+ cations (Masters and Selkoe 2012). Amorphous aggregates are commonly reported in previous studies due to the use of relatively high Aβ concentrations (usually 50–100 μM) (Miura et al. 2000; Tougu et al. 2011). A recent study has demonstrated that 2 μM Aβ in the presence of substoichiometric Cu2+ cations was still sufficient for fibril growth. The authors proposed that the low peptide concentration required for fibril formation in the presence of Cu2+ cations is reminiscent of the crystallization of proteins (Sarell et al. 2010), in which high protein concentrations lead to a high propensity for overt precipitation rather than ordered crystals. Similarly, suprastoichiometric amounts of Cu2+ cations could cause excessive cross-linking of Aβ42, resulting in formation of amorphous aggregates or higher–order oligomers (Jones and Mezzenga 2012).

In conclusion, our AFM force spectroscopy and imaging results suggest that Cu2+ cations increase interpeptide interactions; therefore it is reasonable to assume that Cu2+ cations promote both the initial and the elongation phases of Aβ42 aggregation. Importantly, the single molecule force spectroscopy studies directly demonstrate the alterations in peptide conformation in the misfolded dimers and how the N–terminal residues aid in dimer stabilization. These findings may have relevance for understanding disease mechanisms and potential therapeutic strategies, such as metal dyshomeostasis (Bush and Tanzi 2008; Kenche and Barnham 2011).

Supplementary Material

Table 1.

Summary of the most probable contour length (MPCL) and the most probable rupture force (MPRF) of force spectroscopy in the presence and absence of Cu2+ cations at all pH.

| MPRF (pN) | MPCL (nm) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| without Cu | with Cu | without Cu | with Cu | |

| pH 7.4 | 41.3 ± 7.6 | 47.3 ± 1.2 | 53.6 ± 9.7 | 31.6 ± 3.5 |

| pH 6.8 | 41.6 ± 2.0 | 50.2 ± 2.6 | 50.7 ± 3.9 | 32.0 ± 9.2 |

| pH 6.0 | 53.3 ± 2.1 | 77.2 ± 2.5 | 45.4 ± 1.8 | 28.1 ± 5.5 |

| pH 5.0 | 64.2 ± 7.8 | 84.8 ± 1.1 | 52.4 ± 1.2 | 25.8 ± 4.7 |

| pH 4.0 | 61.8 ± 7.0 | 63.5 ± 1.6 | 32.9 ± 1.0 | 30.5 ± 0.1 |

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Krasnoslobodtsev, A. Portillo, Zenghan Tong, Yuliang Zhang and other group members for insightful suggestions and discussions. The work was supported by grants to Y.L.L. from the National Institutes of Health (NIH: GM096039), U.S. Department of Energy Grant DE-FG02-08ER64579, the Nebraska Research Initiative and grants to D.B.T. from NIH (NS038328, AG041295) and the Jim Easton Consortium for Drug Development and Biomarkers.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supporting Information Available: The estimation of contour length of all tethers; the force spectroscopy results in the presence and absence of Cu2+ cations at pH 6.8 and 6.0. This material is available free of charge via the Internet.

References

- Ahmed M, Davis J, Aucoin D, Sato T, Ahuja S, Aimoto S, Elliott JI, Van Nostrand WE, Smith SO. Structural conversion of neurotoxic amyloid-beta(1–42) oligomers to fibrils. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17(5):561–567. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali-Torres J, Rodriguez-Santiago L, Sodupe M. Computational calculations of pKa values of imidazole in Cu(II) complexes of biological relevance. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2011;13(17):7852–7861. doi: 10.1039/c0cp02319a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atwood CS, Moir RD, Huang X, Scarpa RC, Bacarra NM, Romano DM, Hartshorn MA, Tanzi RE, Bush AI. Dramatic aggregation of Alzheimer abeta by Cu(II) is induced by conditions representing physiological acidosis. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(21):12817–12826. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.21.12817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnham KJ, Masters CL, Bush AI. Neurodegenerative diseases and oxidative stress. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3(3):205–214. doi: 10.1038/nrd1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer MK, Clausen-Schaumann H. Mechanochemistry: the mechanical activation of covalent bonds. Chem Rev. 2005;105(8):2921–2948. doi: 10.1021/cr030697h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitan G, Kirkitadze MD, Lomakin A, Vollers SS, Benedek GB, Teplow DB. Amyloid beta -protein (Abeta) assembly: Abeta 40 and Abeta 42 oligomerize through distinct pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(1):330–335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222681699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush AI, Tanzi RE. Therapeutics for Alzheimer’s disease based on the metal hypothesis. Neurotherapeutics. 2008;5(3):421–432. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WT, Liao YH, Yu HM, Cheng IH, Chen YR. Distinct effects of Zn2+, Cu2+, Fe3+, and Al3+ on amyloid-beta stability, oligomerization, and aggregation: amyloid-beta destabilization promotes annular protofibril formation. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(11):9646–9656. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.177246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson CM. Protein folding and misfolding. Nature. 2003;426(6968):884–890. doi: 10.1038/nature02261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong J, Canfield JM, Mehta AK, Shokes JE, Tian B, Childers WS, Simmons JA, Mao Z, Scott RA, Warncke K, Lynn DG. Engineering metal ion coordination to regulate amyloid fibril assembly and toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(33):13313–13318. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702669104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drew SC, Masters CL, Barnham KJ. Alanine-2 carbonyl is an oxygen ligand in Cu2+ coordination of Alzheimer’s disease amyloid-beta peptide--relevance to N-terminally truncated forms. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131(25):8760–8761. doi: 10.1021/ja903669a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faller EM, Brown DL. Modulation of microtubule dynamics by the microtubule-associated protein 1a. J Neurosci Res. 2009;87(5):1080–1089. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faller P. Copper and zinc binding to amyloid-beta: coordination, dynamics, aggregation, reactivity and metal-ion transfer. Chembiochem. 2009;10(18):2837–2845. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200900321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fezoui Y, Teplow DB. Kinetic studies of amyloid beta-protein fibril assembly. Differential effects of alpha-helix stabilization. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(40):36948–36954. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204168200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Casado A, Dam HH, Yilmaz MD, Florea D, Jonkheijm P, Huskens J. Probing multivalent interactions in a synthetic host-guest complex by dynamic force spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133(28):10849–10857. doi: 10.1021/ja2016125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haupt C, Leppert J, Ronicke R, Meinhardt J, Yadav JK, Ramachandran R, Ohlenschlager O, Reymann KG, Gorlach M, Fandrich M. Structural basis of beta-amyloid-dependent synaptic dysfunctions. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2012;51(7):1576–1579. doi: 10.1002/anie.201105638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong L, Carducci TM, Bush WD, Dudzik CG, Millhauser GL, Simon JD. Quantification of the binding properties of Cu2+ to the amyloid beta peptide: coordination spheres for human and rat peptides and implication on Cu2+-induced aggregation. J Phys Chem B. 2010;114(34):11261–11271. doi: 10.1021/jp103272v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong L, Simon JD. Insights into the thermodynamics of copper association with amyloid-beta, alpha-synuclein and prion proteins. Metallomics. 2011;3(3):262–266. doi: 10.1039/c0mt00052c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Atwood CS, Moir RD, Hartshorn MA, Tanzi RE, Bush AI. Trace metal contamination initiates the apparent auto-aggregation, amyloidosis, and oligomerization of Alzheimer’s Abeta peptides. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2004;9(8):954–960. doi: 10.1007/s00775-004-0602-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung YH, Bush AI, Cherny RA. Copper in the brain and Alzheimer’s disease. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2010;15(1):61–76. doi: 10.1007/s00775-009-0600-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innocenti M, Salvietti E, Guidotti M, Casini A, Bellandi S, Foresti ML, Gabbiani C, Pozzi A, Zatta P, Messori L. Trace copper(II) or zinc(II) ions drastically modify the aggregation behavior of amyloid-beta1–42: an AFM study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;19(4):1323–1329. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jomova K, Vondrakova D, Lawson M, Valko M. Metals, oxidative stress and neurodegenerative disorders. Mol Cell Biochem. 2010;345(1–2):91–104. doi: 10.1007/s11010-010-0563-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones OG, Mezzenga R. Inhibiting, promoting, and preserving stability of functional protein fibrils. Soft Matter. 2012;8(4):876–895. doi: 10.1039/C1SM06643A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kenche VB, Barnham KJ. Alzheimer’s disease & metals: therapeutic opportunities. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;163(2):211–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01221.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim BH, Palermo NY, Lovas S, Zaikova T, Keana JF, Lyubchenko YL. Single-molecule atomic force microscopy force spectroscopy study of Abeta-40 interactions. Biochemistry. 2011;50(23):5154–5162. doi: 10.1021/bi200147a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkitadze MD, Condron MM, Teplow DB. Identification and characterization of key kinetic intermediates in amyloid beta-protein fibrillogenesis. J Mol Biol. 2001;312(5):1103–1119. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klug GM, Losic D, Subasinghe SS, Aguilar MI, Martin LL, Small DH. Beta-amyloid protein oligomers induced by metal ions and acid pH are distinct from those generated by slow spontaneous ageing at neutral pH. Eur J Biochem. 2003;270(21):4282–4293. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasnoslobodtsev AV, Shlyakhtenko LS, Lyubchenko YL. Probing Interactions within the synaptic DNA-SfiI complex by AFM force spectroscopy. J Mol Biol. 2007;365(5):1407–1416. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.10.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazo ND, Grant MA, Condron MC, Rigby AC, Teplow DB. On the nucleation of amyloid beta-protein monomer folding. Protein Sci. 2005;14(6):1581–1596. doi: 10.1110/ps.041292205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CJ, Huang HC, Jiang ZF. Cu(II) interaction with amyloid-beta peptide: a review of neuroactive mechanisms in AD brains. Brain Res Bull. 2010;82(5–6):235–242. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubchenko YL, Kim BH, Krasnoslobodtsev AV, Yu J. Nanoimaging for protein misfolding diseases. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol. 2010;2(5):526–543. doi: 10.1002/wnan.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masters CL, Selkoe DJ. Biochemistry of Amyloid β-Protein and Amyloid Deposits in Alzheimer Disease. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine. 2012 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura T, Mitani S, Takanashi C, Mochizuki N. Copper selectively triggers beta-sheet assembly of an N-terminally truncated amyloid beta-peptide beginning with Glu3. J Inorg Biochem. 2004;98(1):10–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura T, Suzuki K, Kohata N, Takeuchi H. Metal binding modes of Alzheimer’s amyloid beta-peptide in insoluble aggregates and soluble complexes. Biochemistry. 2000;39(23):7024–7031. doi: 10.1021/bi0002479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami K, Irie K, Ohigashi H, Hara H, Nagao M, Shimizu T, Shirasawa T. Formation and stabilization model of the 42-mer Abeta radical: implications for the long-lasting oxidative stress in Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127(43):15168–15174. doi: 10.1021/ja054041c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murariu M, Dragan ES, Drochioiu G. Synthesis and mass spectrometric characterization of a metal-affinity decapeptide: copper-induced conformational changes. Biomacromolecules. 2007;8(12):3836–3841. doi: 10.1021/bm700793g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olofsson A, Lindhagen-Persson M, Vestling M, Sauer-Eriksson AE, Öhman A. Quenched hydrogen/deuterium exchange NMR characterization of amyloid-β peptide aggregates formed in the presence of Cu2+ or Zn2+ FEBS Journal. 2009;276(15):4051–4060. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olubiyi OO, Strodel B. Structures of the amyloid beta-peptides Abeta1-40 and Abeta1–42 as influenced by pH and a D-peptide. J Phys Chem B. 2012;116(10):3280–3291. doi: 10.1021/jp2076337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono K, Condron MM, Teplow DB. Structure-neurotoxicity relationships of amyloid beta-protein oligomers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(35):14745–14750. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905127106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parthasarathy S, Long F, Miller Y, Xiao Y, McElheny D, Thurber K, Ma B, Nussinov R, Ishii Y. Molecular-level examination of Cu2+ binding structure for amyloid fibrils of 40-residue Alzheimer’s beta by solid-state NMR spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133(10):3390–3400. doi: 10.1021/ja1072178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portillo AM, Krasnoslobodtsev AV, Lyubchenko YL. Effect of electrostatics on aggregation of prion protein Sup35 peptide. J Phys Condens Matter. 2012;24(16):164205. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/24/16/164205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauk A. The chemistry of Alzheimer’s disease. Chem Soc Rev. 2009;38(9):2698–2715. doi: 10.1039/b807980n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Mancia S, Perez-Neri I, Rios C, Tristan-Lopez L, Rivera-Espinosa L, Montes S. The transition metals copper and iron in neurodegenerative diseases. Chem Biol Interact. 2010;186(2):184–199. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts BR, Ryan TM, Bush AI, Masters CL, Duce JA. The role of metallobiology and amyloid-beta peptides in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem. 2012;120(Suppl 1):149–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarell CJ, Syme CD, Rigby SE, Viles JH. Copper(II) binding to amyloid-beta fibrils of Alzheimer’s disease reveals a picomolar affinity: stoichiometry and coordination geometry are independent of Abeta oligomeric form. Biochemistry. 2009;48(20):4388–4402. doi: 10.1021/bi900254n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarell CJ, Wilkinson SR, Viles JH. Substoichiometric levels of Cu2+ ions accelerate the kinetics of fiber formation and promote cell toxicity of amyloid-{beta} from Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(53):41533–41540. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.171355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt L, Ludwig M, Gaub HE, Tampe R. A metal-chelating microscopy tip as a new toolbox for single-molecule experiments by atomic force microscopy. Biophys J. 2000;78(6):3275–3285. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76863-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin BK, Saxena S. Direct evidence that all three histidine residues coordinate to Cu(II) in amyloid-beta1-16. Biochemistry. 2008;47(35):9117–9123. doi: 10.1021/bi801014x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DP, Ciccotosto GD, Tew DJ, Fodero-Tavoletti MT, Johanssen T, Masters CL, Barnham KJ, Cappai R. Concentration dependent Cu2+ induced aggregation and dityrosine formation of the Alzheimer’s disease amyloid-beta peptide. Biochemistry. 2007;46(10):2881–2891. doi: 10.1021/bi0620961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DP, Smith DG, Curtain CC, Boas JF, Pilbrow JR, Ciccotosto GD, Lau TL, Tew DJ, Perez K, Wade JD, Bush AI, Drew SC, Separovic F, Masters CL, Cappai R, Barnham KJ. Copper-mediated amyloid-beta toxicity is associated with an intermolecular histidine bridge. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(22):15145–15154. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600417200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder SW, Ladror US, Wade WS, Wang GT, Barrett LW, Matayoshi ED, Huffaker HJ, Krafft GA, Holzman TF. Amyloid-beta aggregation: selective inhibition of aggregation in mixtures of amyloid with different chain lengths. Biophys J. 1994;67(3):1216–1228. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80591-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparks DL, Schreurs BG. Trace amounts of copper in water induce beta-amyloid plaques and learning deficits in a rabbit model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(19):11065–11069. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1832769100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stellato F, Menestrina G, Serra MD, Potrich C, Tomazzolli R, Meyer-Klaucke W, Morante S. Metal binding in amyloid beta-peptides shows intra- and inter-peptide coordination modes. Eur Biophys J. 2006;35(4):340–351. doi: 10.1007/s00249-005-0041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streltsov VA, Titmuss SJ, Epa VC, Barnham KJ, Masters CL, Varghese JN. The structure of the amyloid-beta peptide high-affinity copper II binding site in Alzheimer disease. Biophys J. 2008;95(7):3447–3456. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.134429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroud JC, Liu C, Teng PK, Eisenberg D. Toxic fibrillar oligomers of amyloid-beta have cross-beta structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203193109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulchek TA, Friddle RW, Langry K, Lau EY, Albrecht H, Ratto TV, DeNardo SJ, Colvin ME, Noy A. Dynamic force spectroscopy of parallel individual Mucin1-antibody bonds. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(46):16638–16643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505208102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syme CD, Nadal RC, Rigby SE, Viles JH. Copper binding to the amyloid-beta (Abeta) peptide associated with Alzheimer’s disease: folding, coordination geometry, pH dependence, stoichiometry, and affinity of Abeta-(1–28): insights from a range of complementary spectroscopic techniques. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(18):18169–18177. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313572200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tougu V, Tiiman A, Palumaa P. Interactions of Zn(II) and Cu(II) ions with Alzheimer’s amyloid-beta peptide. Metal ion binding, contribution to fibrillization and toxicity. Metallomics. 2011;3(3):250–261. doi: 10.1039/c0mt00073f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh DM, Lomakin A, Benedek GB, Condron MM, Teplow DB. Amyloid beta-protein fibrillogenesis. Detection of a protofibrillar intermediate. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(35):22364–22372. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.35.22364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Pritzker M, Fung SY, Sheng Y, Wang W, Chen P. Anion effect on the nanostructure of a metal ion binding self-assembling peptide. Langmuir. 2006;22(20):8553–8562. doi: 10.1021/la061238p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Lyubchenko YL. Early stages for Parkinson’s development: alpha-synuclein misfolding and aggregation. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2009;4(1):10–16. doi: 10.1007/s11481-008-9115-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Malkova S, Lyubchenko YL. alpha-Synuclein misfolding: single molecule AFM force spectroscopy study. J Mol Biol. 2008;384(4):992–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Warnke J, Lyubchenko YL. Nanoprobing of alpha-synuclein misfolding and aggregation with atomic force microscopy. Nanomedicine. 2011;7(2):146–152. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou J, Kajita K, Sugimoto N. Cu(2+) Inhibits the Aggregation of Amyloid beta-Peptide(1–42) in vitro. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2001;40(12):2274–2277. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010618)40:12<2274::AID-ANIE2274>3.0.CO;2–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.