Abstract

Objective

To estimate the effect of progestin-only vs. combined hormonal contraceptive pills on rates of breastfeeding continuation in postpartum women. Secondary outcomes include infant growth parameters, contraceptive method continuation and patient satisfaction with breastfeeding and contraceptive method.

Methods

In this randomized controlled trial, postpartum breastfeeding women who desired oral contraceptives were assigned to progestin-only vs. combined hormonal contraceptive pills. At two and eight weeks postpartum, participants completed in-person questionnaires that assessed breastfeeding continuation and contraceptive use. Infant growth parameters including weight, length and head circumference were assessed at eight weeks postpartum. Telephone questionnaires assessing breastfeeding, contraceptive continuation and satisfaction were completed at 3-7 weeks and 4 and 6 months. Breastfeeding continuation was compared between groups using Cox proportional hazards regression. Differences in baseline demographic characteristics and in variables between the two intervention groups were compared using chi-square tests, Fisher’s Exact test, or two-sample t-tests as appropriate.

Results

Breastfeeding continuation rates, contraceptive continuation, and infant growth parameters did not differ between users of progestin-only and combined hormonal contraceptive pills. Infant formula supplementation and maternal perception of inadequate milk supply were associated with decreased rates of breastfeeding in both groups.

Conclusions

Choice of combined or progestin-only birth control pills administered two weeks postpartum did not adversely affect breastfeeding continuation.

INTRODUCTION

Contraception for breastfeeding women should be highly effective and not impair lactation. Prompt initiation of contraception after delivery reduces the likelihood of unintended pregnancy and, in low resource settings, reduces maternal and infant morbidity and mortality (1, 2). Progestin-only pills are traditionally the oral contraceptive of choice because of concerns that combined oral contraceptive pills may reduce breast milk production and, in turn, result in early discontinuation of breastfeeding or poor infant growth (3-7). In non-breastfeeding women, combined pills are known to have several advantages over progestin-only pills: fewer side effects, better efficacy, and higher continuation rates (8, 9). Nonetheless, if combined pills diminish the quality or quantity of breast milk in a clinically meaningful way, then progestin-only pills will be preferable for most breastfeeding women desiring oral contraception. If combined pills have a negligible clinical effect on breastfeeding outcomes, then combined pills are a better contraceptive choice for most breastfeeding women.

Our aim was to estimate the effect of postpartum use of progestin-only pills vs. combined pills on breastfeeding continuation at 8 weeks postpartum. Secondary outcomes included infant growth, contraceptive method continuation, and patient satisfaction with both breastfeeding and the assigned oral contraceptive.

METHODS

This double-blind randomized trial was conducted at the University of New Mexico between January 2005 and June 2008. The University of New Mexico Human Research Review Committee approved the study and all women gave written informed consent. We enrolled postpartum women aged 15-45 who delivered at the University of New Mexico Hospital (UNMH), who intended to breastfeed, planned to use oral contraceptives as their family planning method and were willing to be randomized to either progestin-only pills or combined pills. Women were excluded if they had: (1) medical contraindications to combined pills, including a history of venous thromboembolism, uncontrolled hypertension, or complex migraine headaches; (2) preterm birth (<37 weeks); (3) a small for gestational age infant (<2500 gram) or large for gestational age infant (>4500 grams); or (4) an infant with a major congenital anomaly.

Study information was distributed via a flyer at the 35-week visit to women receiving prenatal care at University of New Mexico Health Sciences affiliated clinics and who planned to deliver at UNMH. Research nurses approached eligible subjects after delivery and provided details about the study. Monetary compensation of $20 was provided at enrollment, two weeks and two months postpartum, for a total of $60 for women who completed the entire study.

Consented participants completed a questionnaire that included patient characteristics including insurance type, smoking history, prior breastfeeding history, and history of prior contraceptive use. Baseline infant length, weight, and head circumference (occipitofrontal) measurements were also obtained using a study-dedicated scale used throughout the subject’s participation to avoid measurement inconsistencies. At enrollment, in order to ensure that all women had access to contraception whether or not they continued in the study, women were given an envelope containing a written prescription for the oral contraceptive of their provider’s choice to be filled in case they decided against study participation.

One week postpartum, participants were contacted by phone. Those who discontinued breastfeeding or who no longer wished to participate were encouraged to start contraception and follow up with a routine postpartum visit. Those who continued breastfeeding and reaffirmed their interest in participation were scheduled for a two-week study visit where they were randomized to the study medications. The randomization sequence was generated in blocks of six by a General Clinical Research Center (GCRC) biostatistician. The randomization consisted of forcing each consecutive block of six subject identifications to have precisely three treatment assignments from each of the two groups, but randomly permuting the order of those assignments using standard statistical software (SAS).

The randomization list was emailed to the research pharmacist, who alone had access to randomization information for the duration of the study. The research nurse notified the research pharmacist when randomizations were needed and the research pharmacist dispensed the initial supply of blinded medication that was indicated on the randomization list, assigning subjects to the next available treatment.

At the two-week study visit, participants completed a questionnaire, a growth assessment of their infant and received study medication. The progestin-only pills group took 0.35 mg norethindrone once a day orally and the combined pills group took 1 mg of norethindrone and 0.035 mg of ethinyl estradiol once a day orally for 21 days followed by seven days of placebo pills. We chose norethindrone-containing combined oral contraceptives and progestin-only pills to eliminate the potential effect of the type of progestin on oral contraceptive continuation (10). The norethindrone dose in the combined oral contraceptives was higher than that in the progestin-only pills, reflecting conventional use. The research pharmacist prepared pill packs by removing assigned pills from their blister packs and placing them in red plastic capsules. All pills were placed in identical monthly pill dispensers to disguise their appearance. Since there were seven days of placebo in the combined pills but not in the progestin-only pills arm, the pharmacist ensured that cells were filled in the proper order, numbered from 1 through 28. Once filled by the research pharmacist, the cells were taped shut until the subject needed the product for that block of days.

At two weeks postpartum, participants returned to the University of New Mexico Hospital and met with the research nurse. At this visit, women completed a questionnaire regarding breastfeeding progress, including continuation, supplementation with formula, the perception of adequate milk supply and satisfaction with breastfeeding. Infant growth parameters (weight, height and head circumference) were obtained and plotted on a growth curve. Women received eight weeks of the previously blinded oral contraceptives at this visit and the research nurse observed the woman taking her first pill. The research nurse instructed the subjects about the importance of taking the pills in order.

Participants were telephoned weekly by the research nurse between three and seven weeks postpartum and completed a verbal questionnaire that addressed continuation of and satisfaction with breastfeeding, the use of supplemental formula and satisfaction with the oral contraceptive.

At two months postpartum, participants returned to the hospital for a follow-up visit and completed a research nurse-administered questionnaire identical to the phone follow-up questionnaires. The infant’s length, weight, and head circumference were obtained and plotted on the growth curve. Subjects received an additional four months of oral contraceptives, prepared by the research pharmacist in the same manner as the initial supply. Participants were contacted by telephone at four and six months and completed the same questionnaire.

All study personnel and participants were blinded to treatment assignment for the duration of the study. The randomization code was unlocked and revealed to the researchers only after subject recruitment and data collection were complete.

Our primary outcome measure was the continuation of breastfeeding in women using progestin-only pills compared to women using combined pills at eight weeks postpartum. Secondary endpoints included breastfeeding rates at four and six months postpartum. We chose eight weeks as the time point for our primary breastfeeding continuation endpoint with the expectation that any negative effect of combined oral contraceptives on breastfeeding would be evident by then. Secondary outcome measures were infant weight and length, and continuation and satisfaction with the contraceptive method. Additional analyses examined reasons for discontinuing breastfeeding, discontinuing oral contraceptives, and for supplementing infant feeding with formula.

Sample size calculation, based on the primary study aim, indicated that 120 subjects divided equally between the two groups would provide a power of 80% at a two-sided significance level of 5% to detect a difference in continuation of breastfeeding of 35% in the combined pills group vs. 60% in the progestin-only pills group at eight weeks postpartum. The calculation was based on the assumption that 50% of women would still be breastfeeding at eight weeks postpartum and that the study was powered for a hazard ratio of two. Anticipating a 20 percent loss to follow-up, this number was increased to 150 study subjects. Recruitment was expanded to 200 patients due to a higher than expected loss of subjects between enrollment and randomization.

Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS Version 9.2. Differences in baseline demographic characteristics and in variables between the two intervention groups were compared using chi-square tests, Fisher’s Exact test, or two-sample t-tests as appropriate. Significance for all analyses was set at p < .05.

A survival model was used for analysis of the primary outcome of breastfeeding duration. Continuation of breastfeeding was compared between the two groups using Cox proportional hazards regression adjusting for time-varying covariates of formula supplementation (supplemented with formula in the time period preceding each contact) and adequate milk production (the woman’s perception that milk production was adequate in the time period preceding each contact). Breastfeeding data duration was censored from two sources: women still breastfeeding at the end of the study, and women in the study for some number of weeks but with who contact was lost prior to 6 months (loss to follow-up). Although the main study endpoint was eight weeks, the survival analysis used the full six-month follow-up period. Treatment group was fit as a factor in the model; the variables “prior OC history” and “prior breastfeeding history” (where there was some imbalance of groups at baseline) were entered as covariates. The time-varying covariates “currently supplementing” and “have concerns about milk supply” were entered as well (for the prior time period). For the time-varying covariates, when there was a missing value for a time period, the last available value was carried forward. No similar data imputation was needed for the primary outcome of breastfeeding duration.

While contact times were discrete (weeks 2-8, and months 4 and 6), an exact date for breastfeeding discontinuation was determined by the interviewer, allowing times until stopping breastfeeding to be treated as a continuous variable. Subjects who discontinued breastfeeding prior to 8 weeks were discontinued from the study and infant growth parameters were not obtained at 8 weeks.

Two-sample t-tests were used to analyze the two groups for measures of infant length and weight. Measures of oral contraceptive continuation and satisfaction were assessed by logistic regression after adjusting for prior use of oral contraceptives.

RESULTS

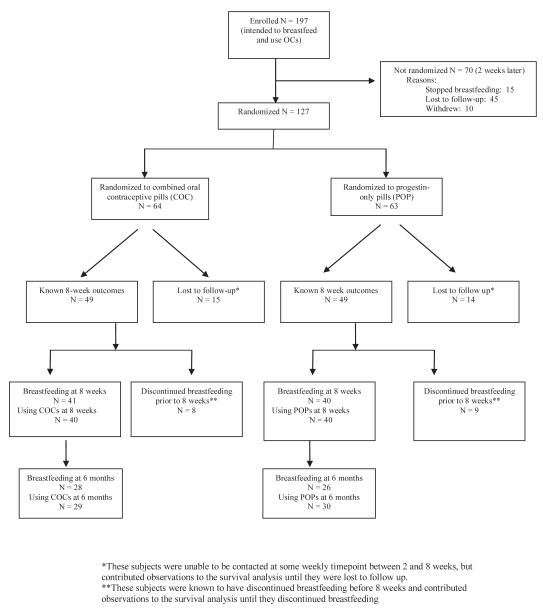

A total of 197 postpartum women who met inclusion criteria were enrolled prior to discharge from the hospital. At the one-week phone call 127 (63%) remained eligible and were randomized; 64 received combined pills and 63 received progestin-only pills. Outcomes of study subjects are summarized in a flow diagram (Figure 1). Seventy enrolled patients were not randomized, most commonly because they did not keep their follow-up appointment. Women who were not randomized were less likely to be high school graduates and less likely to be employed than those who were randomized(Table 1).

Figure 1.

Study flow

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of combined oral contraceptive (COC) and progestin-only oral contraceptive (POP) groups

| Characteristic | Combined oral contraceptive pills (COC) N = 64 |

Progestin-only contraceptive pills (POP) N = 63 |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 23.8 ± 4.4 | 25.0 ± 5.4 | NS |

| High school graduate | 38 (59.4%) | 29 (46.8%) | NS |

| Multiparous | 37 (57.8%) | 38 (61.3%) | NS |

| Married/living as married | 50 (78.1%) | 43 (69.4%) | NS |

| Race | |||

| Hispanic | 54 (84.4%) | 55 (87.3%) | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 6 (9.4%) | 5 (7.9%) | NS |

| Other | 4 (6.3%) | 3 (4.8%) | |

| Medicaid | 21 (32.8%) | 18 (29.5%) | NS |

| Private insurance | 10 (15.6%) | 5 (8.1%) | NS |

| Employed | 18 (28.1%) | 16 (25.8%) | NS |

| Smoker | 2 (3.1%) | 3 (4.8%) | NS |

| Breastfed with a previous pregnancy |

27 (42.2%) | 37 (59.7%) | 0.05 |

| Used oral contraceptives in the past |

45 (70.3%) | 29 (46.8%) | 0.01 |

Patient characteristics were similar between the two groups, except that combined pill users were more likely to have used oral contraceptive pills previously while progestin-only pills users were more likely to have breastfed previously (Table 1). At two weeks postpartum, prior to initiation of pills, the number of women exclusively breastfeeding and the number of women who perceived an inadequate milk supply did not differ between groups (Table 1); 63.8% of all study participants were exclusively breastfeeding and 22% perceived inadequate milk supply. No protocol deviations occurred.

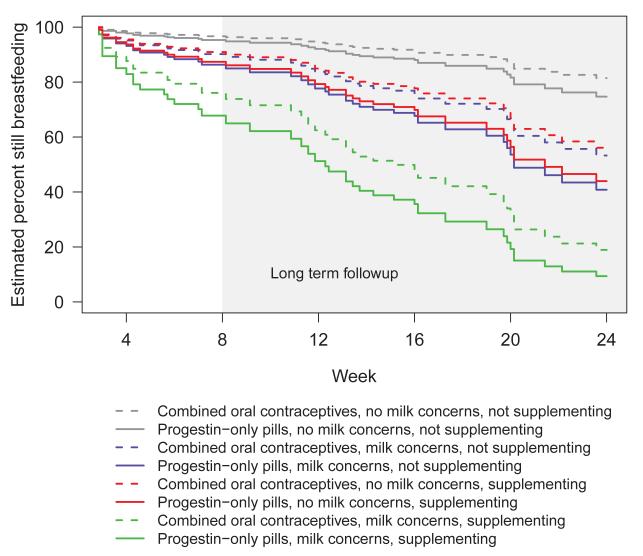

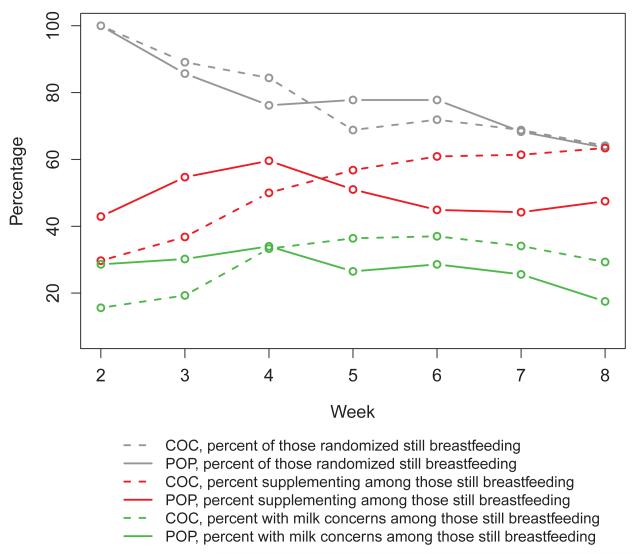

Survival analysis demonstrated no difference in the primary outcome of breastfeeding continuation between the two oral contraceptive groups over the full six months of follow-up (Figure 2). Maternal breastfeeding supplementation with formula (“supplementing”) or maternal concern for inadequate milk supply (“milk concerns”) was predictive of breastfeeding discontinuation (Table 2). At the primary endpoint of eight weeks, the number of women continuing to breastfeed between the two groups was not different: 64.1% of women in the combined pills group and 63.5% in the progestin-only pills group were still breastfeeding (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Cox proportional hazards regression for breastfeeding continuation fit with time-varying covariates of milk concerns and supplementing. N = 64 for combined oral contraceptives and N = 63 for progestin-only pills.

Table 2.

Outcomes at study endpoint (8 weeks): Infant growth,a breastfeeding continuationb, oral contraceptive usec and satisfaction with breastfeeding and oral contraceptivesc

| Outcome | 2 weeks | 8 weeks | Delta 2 weeks to 8 weeks |

P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COC N = 64 |

POP N = 63 |

COC N = 41 |

POP N = 40 |

COC N = 41 |

POP N = 40 |

||

| Infant length (mean) |

51.5 | 51.7 | 56.8 | 57.0 | 5.6 | 5.3 | .49 |

| Infant weight (mean) |

3.7 | 3.7 | 5.08 | 5.20 | 1.42 | 1.52 | .36 |

| Infant occipitofrontal circumference (mean)d |

36.0 | 36.1 | 39.0 | 39.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | .84 |

| Report of any breastfeedinge |

--- | --- | 41g/64 (64%) |

40g/63 (64%) |

Table 3 NS |

||

| Report of using pillse |

--- | --- | 41/42 (98%) |

40/40 (100%) |

1.00h | ||

| Somewhat or very satisfied with breastfeeding |

95% | 95% | 38/41 (93%) |

38/40 (95%) |

1.00 | ||

| Somewhat or very satisfied with OCs?f |

--- | --- | 41/41 (100%) |

40/40 (100%) |

1.00 | ||

Two sample t-test

Survival analysis

Fisher Exact test

One missing value at 2 weeks and 2 missing values at 8 weeks

Inclusion criteria required breastfeeding to continue in the study

Women did not begin OCs until 2 weeks

Still actively breastfeeding at 8 weeks

These are not ps of the deltas—just differences at 8 weeks

Figure 3.

Breastfeeding outcomes at 8 weeks: Continued breastfeeding in combined oral contraceptive (COC, N = 64) vs. progestin-only pill (POP, n=63) groups. Numbers still breastfeeding for weeks 2-8 were 64, 57, 54, 44, 46, 44, 41 for COC, and 63, 54, 48, 49, 49, 43, 40 for POP.

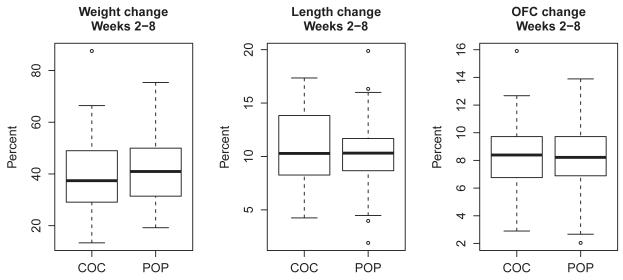

Over the eight-week study period, growth parameters between infants did not differ between groups, either in percent change in weight (p = .56), length (p = .41) or head circumference (p = .79) (Figure 4). The box plots in Figure 4 demonstrate considerable overlap for the distributions of these variables between the two groups. At weekly time points between two and eight week visits, breastfeeding women did not differ in the percent who continued to use pills. Of those continuing to breastfeed at eight weeks, 98% of participants assigned to combined pills and 100% assigned to progestin-only pills continued their pills (Figure 3). Additionally, the number of women lost to follow-up was similar between the two groups at eight weeks (p > 0.99).

Figure 4.

Infant growth: Changes in weight, length and occipitofrontal measurements in infants of women using combined oral contraceptive (COC) versus those using progestin-only pills (POP) between weeks 2 and 8.

Groups did not differ in reasons cited for discontinuing breastfeeding or contraceptive pills during the six months of the study (Table 3). Of women who discontinued breastfeeding, 44% of the progestin-only pills group and 55% of the combined pills group reported stopping due to a perceived lack of milk supply (p > .05). Of those who discontinued their oral contraceptive, 23% of progestin-only pills users and 21% of combined pill users reported stopping due to a perceived negative impact of the assigned oral contraceptive on milk supply. Other reasons women gave for discontinuation of breastfeeding or oral contraceptives are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Primary reason for discontinuing breastfeeding and oral contraceptives**

| Reasons for discontinuation | COC (N%) |

Progestin-only (N%) |

P value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breastfeeding | |||

| Milk supply | 11(55) | 12(44) | |

| Return to school/work | 3(15) | 3(11) | |

| Uncomfortable/difficult | 1(5) | 2(7) | NS |

| Baby problem/latch/infection | 3(15) | 7(26) | |

| Mother issue: infection/pregnant/changed mind |

2(10) | 3(11) | |

| Oral contraceptives | |||

| Milk supply problem | 4(21) | 3(23) | |

| Side effects | 6(32) | 5(38) | |

| Not sexually active | 0 | 1(8) | NS |

| Use problem: using another method/couldn’t remember/ran out |

7(37) | 3(23) | |

| Pregnant | 2(11) | 1(8) |

Fisher Exact test

Includes primary reason for breastfeeding discontinuation through 6 months

Groups at two and eight weeks did not differ in satisfaction with breastfeeding, oral contraceptive use, perception of adequate milk supply, or supplementation with formula (p < 0.05). At eight weeks, all women who continued to breastfeed were somewhat or very satisfied with their oral contraceptive and 93% of combined pills user and 95% of progestin-only pills users were somewhat or very satisfied with breastfeeding. There were no pregnancies reported in the first eight weeks in those continuing in the study and no adverse events reported during the six months of the full follow-up period.

DISCUSSION

We found that breastfeeding duration and infant growth did not differ between women who initiated progestin-only pills vs. combined pills at two weeks postpartum. Reasons cited for discontinuing breastfeeding did not differ between groups; maternal perception of inadequate milk supply was the most common reason cited. We found that introduction of supplementation with formula or a perceived lack of milk supply correlated with breastfeeding discontinuation, while type of oral contraceptive pill used had no effect. Even at two weeks postpartum, about a third of women were already supplementing with formula and a fifth perceived inadequate milk supply.

Breastfeeding rates at eight weeks in our study were similar to rates found in the New Mexico Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) data. Overall, 84% of women in New Mexico initiate breastfeeding; however, only 60% are breastfeeding through two months postpartum (11). Although 64%of our randomized study participants were breastfeeding at eight weeks, only 28.3% were exclusively breastfeeding, agreeing with findings of generally low exclusive breastfeeding rates in US women between six and 12 weeks postpartum (12, 13).

Other studies examining the impact of hormonal contraceptives on lactation and growth have demonstrated mixed results (3-7, 14-16). The most robust was a 1988 quasi-randomized trial of progestin-only pills vs. combined pills that found a lower volume of milk expressed in the combined pill group but no differences between groups in infant growth, breastfeeding continuation, and reasons for breastfeeding discontinuation (14). Earlier trials, limited by methodologic flaws, demonstrate some differences in rates of breastfeeding and few differences in infant and child outcomes (3-5, 15). Additionally, some trials suggest lower pregnancy rates in women taking progestin-only pills (4, 5).

Our study has limitations. The sample size was calculated to identify a 25% difference in continuation of breastfeeding at two months between the two study groups. Our findings highlight the need for a large randomized controlled trial with the aim of demonstrating equivalency between progestin-only pills and combined pills; our results support the feasibility of such a study. The actual loss to follow-up rate in our study was high, explained partly by the high recruitment of subjects from clinics that serve a population of women who are undocumented and mobile. Additionally, the results may not be applicable beyond the patient population studied, who were generally Hispanic and without an identified payment source for health care. Given the extent of early supplementation of breastfeeding with formula in our population, our results apply only to women with ready access to formula. Although women randomized to progestin-only pills were more likely to have breastfed in the past, they would have skewed the results to show more, not less, of an effect on reducing breastfeeding duration; it is unlikely that this difference had an impact on the results of the study. The combined oral contraceptive used in this study contains 35 mcg of ethinyl estradiol, the highest dose in current common use; the lack of an effect on breastfeeding is reassuring with regard to formulations containing lower amounts of ethinyl estradiol.

Recommendations for using or avoiding combined pills in postpartum breastfeeding women vary. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention United States Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use (US MEC) recently updated its guidance on initiation of combined pills for postpartum women, based on evidence that the increased risk of thromboembolism persists through 21 days postpartum. In postpartum breastfeeding women, initiation prior to 21 days is ranked as category 4 (unacceptable health risks); initiation at 21-29 days for women at low risk for thromboembolism is rated category 3 (theoretical or proven risks generally outweigh advantages) because of concerns about a negative impact on breastfeeding, and initiation at > 42 days is rated category 2 (advantages generally outweigh theoretical or proven risks) (17). The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) endorses this recommendation (18). The World Health Organization (WHO) assigns a category 4 (unacceptable health risk) for initiation of combined pills within six weeks of delivery and a category 3 (theoretical or proven risks usually outweigh the advantages) for initiation of combined pills from 6 weeks to 6 months in primarily breastfeeding women (19). The recommendations of the International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF) are similar to those of the WHO (20). In 2010, a Cochrane review concluded that current data were insufficient to make recommendations on the impact of hormonal contraception on milk quality and quantity due to a lack of methodologically sound trials (21).

The lack of recent literature on the impact of combined hormonal contraception on breastfeeding is surprising, given the worldwide popularity of combined oral contraceptives and the importance and prevalence of breastfeeding. If, as our study suggests, there is no difference in impact of progestin-only pills vs. combined pills on breastfeeding continuation or infant outcomes, women who desire an oral contraceptive should be encouraged to use combined pills, initiated no earlier than 21 days postpartum, due to their greater effectiveness and the negative consequences of unintended pregnancy (22). This study demonstrates the feasibility of a larger equivalency study to clarify the clinical impact of combined oral contraceptive use on lactation. Our data are reassuring that combined pills do not have a major impact on breastfeeding continuation or infant growth.

Acknowledgments

Funded by an ACOG Contraceptive grant and by University of New Mexico Clinical and Translational Science Center, #1UL1TT031977-01

Footnotes

Footnote: N’s were 41 and 40, respectively, for COC and POP with weight and length. For occipitofrontal measurement the respective n’s were 40 and 38.

Poster presentation at Reproductive Health, September 30-October 3, 2009, Los Angeles, California

Contributor Information

Eve Espey, University of New Mexico Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

Tony Ogburn, University of New Mexico Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

Larry Leeman, University of New Mexico Department of Family and Community Medicine.

Rameet Singh, University of New Mexico Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

Ronald Schrader, University of New Mexico Department of Biostatistics.

REFERENCES

- 1.Horta B, Bahl R, Martines J, Victora C. Evidence of the long-term effects of breastfeeding; systematic review and meta-analysis. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gartner LM, Morton J, Lawrence RA, et al. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2005;115:496–506. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller GH, Hughes LR. Lactation and genital involution effects of a new low-dose oral contraceptive on breast-feeding mothers and their infants. Obstet Gynecol. 1970 Jan;35(1):44–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diaz S, Peralta O, Juez G, Herreros C, Casado ME, Salvatierra AM, et al. Fertility regulation in nursing women: III. Short-term influence of a low-dose combined oral contraceptive upon lactation and infant growth. Contraception. 1983;27(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/0010-7824(83)90051-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Croxatto HB, Diaz S, Peralta O, Juez G, Herreros C, Casado ME, et al. Fertility regulation in nursing women: IV. Long-term influence of a low-dose combined oral contraceptive initiated at day 30 postpartum upon lactation and infant growth. Contraception. 1983;27(1):13–25. doi: 10.1016/0010-7824(83)90052-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCann MF, Moggia AV, Higgins JE, Potts M, Becker C. The effects of a progestin-only oral contraceptive (levonorgestrel 0.03 mg) on breastfeeding. Contraception. 1989;40(6):635–48. doi: 10.1016/0010-7824(89)90068-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunson TR, McLaurin VL, Grubb GS, Rosman AW. A multicenter clinical trial of a progestin-only oral contraceptive in lactating women. Contraception. 1993;47(1):23–35. doi: 10.1016/0010-7824(93)90106-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hatcher RA, Trussell J, Nelson AL, et al. Contraceptive technology. 20th ed Ardent Media Inc; New York: [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erwin PC. To use or not use combined hormonal oral contraceptives during lactation. Fam Plann Perspect. 1994;26(1):26–30. 33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lawrie TA, Helmerhorst FM, Maitra NK, Kulier R, Bloemenkamp K, Gülmezoglu AM. Types of progestogens in combined oral contraception: effectiveness and side-effects. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011 May 11;(5):CD004861. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004861.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. [Retrieved May 9, 2011];New Mexico Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System( PRAMS) Surveillance Report 2008. Availabale at http://nmhealth.org/erd/pdf/DOH PRAMS 2008.pdf.

- 12.Halderman L, Nelson A. Impact of early postpartum administration of progestin-only hormonal contraceptives compared with nonhormonal contraceptives on short-term breast-feeding patterns. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(6):1250–6. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.123738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. [Retrieved on May 9, 2011];Breastfeeding Among U.S. Children Born 1999—2007, CDC National Immunization Survey. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/NIS_data/index.html.

- 14.World Health Organization (WHO) Task Force on Oral Contraceptives Effects of hormonal contraceptives on breast milk composition and infant growth. Stud Fam Plann. 1988;19:361–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaern T. Effect of an oral contraceptive immediately postpartum on initiation of lactation. Brit Med J. 1967;3:644–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.3.5566.644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nilsson S, Mellbin T, Hofvander Y, Sundelin C, Valentin J, Nygren KG. Long-term followup of children breast-fed by mothers using oral contraceptives. Contraception. 1986;34(5):443–457. doi: 10.1016/0010-7824(86)90054-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MMWR [Retrieved July 30, 2011];Update to CDC’s U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2010: Revised Recommendations for the Use of Contraceptive Methods During the Postpartum Period. 2011 Jul; Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6026a3.htm#tab1. [PubMed]

- 18.ACOG Practice bulletin #73, Use of Hormonal contraception in women with coexisting medical conditions. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; [Retrieved June 10, 2011]. Available at http://www.acog.org/publications/educational_bulletins/pb073.cfm. [Google Scholar]

- 19. [Retrieved November 10, 2010];WHO medical eligibility criteria. (4th ed). 2009 Available at http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241563888_eng.pdf.

- 20. [Retrieved November 10, 2010];International Planned Parenthood Federation: directory of hormonal contraceptives medical and service delivery guidelines. (3rd ed). 2004 Available at http://www.ippf.org/NR/rdonlyres/DD4055C9-8125-474A-9EC9-C16571DD72F5/0/medservdelivery04.pdf.

- 21.Truitt ST, Fraser AB, Gallo MF, Lopez LM, Grimes DA, Schulz KF. Combined hormonal versus nonhormonal versus progestin-only contraception in lactation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2003;(Issue 2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003988. Art. No.: CD003988. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gipson JD, Koenig MA, Hindin MJ. The effects of unintended pregnancy on infant, child, and parental health: a review of the literature. Stud Family Plann. 2008;39:18–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2008.00148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]