Abstract

The voltage-gated Ca2+ channel β subunit (Cavβ) is a cytosolic auxiliary subunit that plays an essential role in regulating the surface expression and gating properties of high-voltage activated (HVA) Ca2+ channels. It is also crucial for the modulation of HVA Ca2+ channels by G proteins, kinases, Ras-related RGK GTPases, and other proteins. There are indications that Cavβ may carry out Ca2+ channel-independent functions. Cavβ knockouts are either non-viable or result in a severe pathophysiology, and mutations in Cavβ have been implicated in disease. In this article, we review the structure and various biological functions of Cavβ, as well as recent advances.

1. INTRODUCTION

Most voltage-gated ion channels are large protein complexes composed of a pore-forming subunit and one or more auxiliary subunits that regulate channel properties. Unlike the majority of voltage-gated channels, high voltage-activated (HVA) Cav1 and Cav2 Ca2+ channels absolutely require an auxiliary β subunit (Cavβ) for plasma membrane expression and proper gating [1]. Cavβ was first purified as part of the complex of skeletal muscle voltage-gated Ca2+ channels and was cloned in 1989 [2-3]. Subsequent cloning efforts revealed four subfamilies of Cavβs (β1-β4), encoded by four distinct genes and each with splice variants. In addition, early studies determined that Cavβ binds with high affinity to the pore-forming α1 subunit (Cavα1) of voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCCs). The high-affinity site is located in the cytoplasmic linker connecting the first two of the four homologous repeats of Cavα1 (i.e., the I-II linker) and was named the α-interaction domain or AID (Fig. 1) [4-6]. Several crystal structures of Cavβ have been solved, providing great insights into the molecular mechanisms of Cavβ function. A comprehensive review on Cavβ is available [7]. Here, we highlight the most important features of Cavβ structure, function, and involvement in cell physiology and pathophysiology.

Figure 1.

VGCC topology and the structure of the Cavβ core in complex with the AID. (A) Schematic representation of the predicted transmembrane topology of the α1 subunit of VGCC. The AID, marked in red, is located on the I-II linker. ‘P’ indicates the pore loops, located between transmembrane regions S5 and S6. ‘+’ indicates the charged amino acids in S4 – the voltage sensor. (B) Amino acid sequence alignment of the AID from the indicated calcium channel α1 subunits. Residues involved in interactions with Cavβ are marked in red, with the most critical residues underlined. Residue numbers are indicated on both sides of the sequence. (C) Cavβ is organized into 5 regions represented schematically in the upper panel. The lower panel shows the crystal structure of the Cavβ3 core in complex with the AID (PDB accession code 1VYT) with the following regions: N-terminus (light blue), the SH3 domain (gold), part of the HOOK region (purple, residues 121-169), and the GK domain (green). Residues 137-166 of the HOOK region were disordered and are not included. The AID region of Cav1.2 (residues 422 to 446) is colored in orange.

2. STRUCTURE OF Cavβ

Based on amino acid sequence alignment, biochemical and functional studies, and molecular modeling, it became clear that Cavβ consists of a conserved core region flanked by non-conserved N- and C-termini (Fig. 1) [8-10]. The core region is composed of two highly conserved regions homologous to the Src homology 3 (SH3) and guanylate kinase (GK) domains, connected by a weakly conserved HOOK region. This SH3-HOOK-GK core can recapitulate many key functions of Cavβ [8, 11-17]. In 2004, three independent research groups reported the crystal structures of the Cavβ core region of β2a, β3 and β4, alone or in complex with the AID [11, 18-19]. The structures confirmed the existence of an SH3-HOOK-GK module in the Cavβ core.

2.1. The N- and C-termini

The amino and carboxyl termini of Cavβ (abbreviated as Cavβ-NT and Cavβ-CT) are highly variable. They have not been crystallized, but an NMR structure has been obtained for the N-terminus of β4. This structure reveals a fold consisting of two α-helices and two anti-parallel β-sheets [20]. There are currently no structures of Cavβ-CT.

2.2 The GK domain

Guanylate kinases catalyze the formation of ADP and GDP from ATP and GMP. The general structural features of guanylate kinases [21-22] are preserved in the Cavβ GK domain (Cavβ-GK), but structural variations exist in the catalytic site, and many key catalytic residues are absent in Cavβ-GK [11, 18-19]. Thus, Cavβ-GK is catalytically inactive. Instead, Cavβ-GK has evolved into a protein interaction module, binding tightly to Cavα1 through its high-affinity interaction with the AID (Fig. 1) [11, 18-19, 23]. Importantly, a large surface of the GK domain remains free to interact with other proteins, such as RGK GTPases (see review by Colecraft and colleagues in this issue) and BK channels [24].

2.3. The SH3 domain and the HOOK region

Classical SH3 domains mediate specific protein-protein interactions. They have a highly conserved hydrophobic surface - the PxxP-binding site, which binds to PxxP-sequences in target proteins. In general, SH3 domains have a well conserved and compact fold consisting of five sequential β-strands (βstrand 1-5) assembled into two orthogonally packed sheets [25]. However, in the Cavβ SH3 domain (Cavβ-SH3) the last two β-strands are non-continuous, separated by the HOOK region [11, 18-19] so that the SH3 domain has the following primary structure: SH3βstrand 1-4-HOOK-SH3βstrand 5 (Fig. 1). The crystal structures show that the PxxP-binding site in Cavβ-SH3 is occluded by part of the HOOK region and a long loop connecting two of the four continuous β-sheets. It is conceivable that these two regions move and expose the PxxP-binding site, either when Cavβ is bound to full-length Cavα1 and/or when it interacts with other partners. Nevertheless, while binding between Cavβ and PxxP-containing proteins, such as dynamin, has been demonstrated [26], the putative PxxP-binding site itself has yet to be implicated.

The HOOK region is variable in length and amino acid sequence among the Cavβ subfamilies. In the crystal structures, a large portion of the HOOK is unresolved due to poor electron density, indicating that it has a high degree of flexibility [11, 18-19]. As will be discussed later, the HOOK region plays an important role in regulating channel inactivation.

2.4. The SH3-GK intramolecular interaction

The crystal structures show that the SH3 and GK domains interact intramolecularly [11, 18-19]. This interaction is strong enough that NT-SH3βstrand 1-4-HOOK module and the SH3βstrand 5-GK-CT module can associate biochemically in vitro and reconstitute the functionality of full length Cavβs in situ [14-15, 17, 19, 27-29].

It has recently been proposed that the intramolecular SH3-GK interaction can be disrupted by dynamin and replaced by an intermolecular interaction resulting in the dimerization of two Cavβs – a proposed mechanism for dynamin-mediated Ca2+ channel endocytosis (discussed later) [30].

2.5. The AID-Cavβ interaction

All Cavβs bind to the 18 amino acid AID in the I-II linker of Cav1 and Cav2 α1 subunits (Fig. 1) [5]. The affinity of the AID-Cavβ interaction ranges from 2 to 54 nM in vitro [5, 15, 31-38]. Single mutations of several conserved residues in the AID, including Y10, W13 and I14, greatly weaken the AID-Cavβ interaction in vitro, and reduce or abolish Cavβ-induced stimulation of Ca2+ channel current in heterologous expression systems [4, 12, 31, 35-36, 39-44], firmly establishing the role of the AID as the principal anchoring domain for Cavβ.

The Cavβ crystal structures reveal a big surprise in regard to the region of Cavβ that interacts with the AID. A 31-amino acid segment of Cavβ, referred to as the β-interacting domain or BID, had been described as the main binding site for the AID [8]. The BID was able to slightly enhance Ca2+ channel current and modulate gating [8], and several BID point mutations were able to weaken the Cavβ/Cavα1 interaction and reduce BID-stimulated Ca2+ channel currents [8, 31]. Thus, it had been generally accepted that Cavβ interacted with Cavα1 primarily through the BID. However, crystal structures of different AID-Cavβ core complexes reveal that the AID does not even contact the BID [11, 18-19, 23], which is buried inside Cavβ. Thus, mutating the BID most likely alters the folding and/or structure of Cavβ, which explains the disruptive effect of BID mutations [8, 31]. The current enhancement by the BID peptide, on the other hand, is likely a non-specific effect, since a random peptide had a similar effect [11].

The crystal structures show that the AID binds to a hydrophobic groove in the GK domain termed the AID-binding pocket or ABP (Fig. 1, α-helices 3, 6 and 9 and some of their flanking loops) [11, 19, 35]. The interactions between the AID and the ABP are extensive and predominantly hydrophobic. These interactions account for the nM affinity of the AID-Cavβ binding. Functional studies show that mutating two or more key residues in the ABP severely weakens or completely abolishes the AID-Cavβ interaction [12-13].

Binding to the AID does not significantly change the Cavβ structure, except for some small and localized changes near the ABP. On the other hand, the AID undergoes a dramatic change in secondary structure when it is engulfed by the ABP. When alone, the AID forms a random coil in solution, as shown by circular dichroism spectrum measurements [18]; when bound to Cavβ, the AID forms a continuous α-helix, as shown in the crystal structures. Importantly, the 22 amino acid region that links the first S6 segment of Cavα1 (i.e., IS6) to the AID seems to form an α-helix [45]. Thus, a picture emerges that in the presence of Cavβ the entire region from IS6 to the AID adopts a continuous α-helical structure. Indeed, two recent crystal structures of a β2 core in complex with large parts of the I-II linker of Cav1 or Cav2 channels show a continuous α-helical structure upstream of the AID (towards IS6), albeit with some differences between Cav1 and Cav2 channels [23]. This rigid structure is crucial for Cavβ regulation of Ca2+ channel gating, as will be discussed later.

3. THE FUNCTIONS OF Cavβ

Cavβ regulates multiple aspects of HVA channel physiology including surface expression, degradation, and gating (Fig. 2). Cavβ is also critical for the regulation of VGCC by lipids, G-proteins, RGK GTPases (Rem, Rem2, Rad and Gem/Kir - reviewed in this issue by Colecraft and colleagues), kinases, phosphatases, and other signaling proteins (Fig. 2) [for a comprehensive review see 7]. We highlight here the most important functions of Cavβ as well as recent advances.

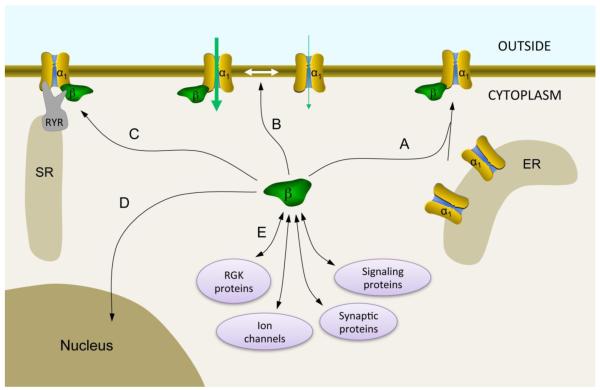

Figure 2.

Major functions of Cavβ. (A) Cavβ enhances Cavα1 localization to the plasma membrane by preventing Cavα1 degradation and exposing ER export signals on Cavα1. (B) Cavβ promotes VGCC gating, resulting in an overall enhancement of current. (C) Cavβ interacts with the ryanodine receptor (RYR) in the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) of muscle cells and is critical for excitation-contraction coupling. (D) Cavβ can be translocated into the nucleus where it may participate in transcriptional regulation. (E) Cavβ interacts directly with many intracellular proteins that regulate VGCC function. The strongest of those regulators are RGK proteins, which potently inhibit VGCCs (reviewed in this issue by Colecraft and colleagues, also see [7]). Other partners include ion channels (e.g., BKCa and bestrophin), synaptic proteins (e.g., synaptotagmin I and RIMI), and signaling proteins (such as kinases, phosphatases, dynamin, and Ahnak) [for extensive review see 7].

3.1. Membrane targeting of Cavβ

Cavβs are cytosolic proteins. This is based both on primary sequence analyses [3, 46] and subcellular localization when Cavβ is expressed alone, in the absence a Cavα1 [16, 42] (a few important exceptions are discussed below). In the presence of Cavα1, Cavβ switches its localization from cytosolic to membrane-bound. This translocation depends on the AID-Cavβ interaction. Single point mutations in the AID of Cav1.2 that disrupt binding with Cavβ abolish both membrane localization and dendritic clustering of Cavβ in hippocampal neurons [47].

Some Cavβs can independently be localized to the plasma membrane [48-49], most notably β2a [50-53]. β2a is tethered to the plasma membrane through dynamic palmitoylation of two cysteines (Cys 3, 4) in its N-terminus [50-53]. However, palmitoylation alone may not be sufficient for membrane localization because implanting the β2a N-terminus into other Cavβs imparts palmitoylation but not membrane localization [51]. Thus, β2a probably possesses some additional determinants that help target it to the plasma membrane. Importantly, membrane tethering of Cavβ coincides with many functional effects, especially slowed inactivation, as we discuss later.

3.2. Cavβ is required for normal channel expression

Cav1 and Cav2 α1 subunits show little or no surface expression and produce very small or no currents when expressed without auxiliary subunits. Upon the coexpression of Ca β, Ca+2 v currents are increased by orders of magnitude [9, 54-57] due to enhanced channel surface expression and open probability. The dramatic increase in surface expression of all Cav1 and Cav2 α1 subunits can be observed both in native cells [58-60] and in various heterologous expression systems with any of the four subfamilies of Cavβ. Thus, Cavβ is required for HVA channel surface expression. The increased surface expression is dependent on Cavβ binding to the AID, as point mutations in the AID or the ABP that weaken or abolish the AID-Cavβ interaction severely reduce or abolish Cavβ-stimulated Ca2+ channel current [4, 12-13]. The GK domain itself can largely recapitulate the chaperone function of full length Cavβs, greatly increasing Ca2+ channel surface expression and current in Xenopus oocytes and mammalian cells [12, 61].

It should be noted that some expression systems, such as Xenopus oocytes, have endogenous Cavβs that can transport a small number of exogenously expressed Cavα1 to the plasma membrane [62]. This yields small Ca2+ channel currents that can be suppressed by antisense oligonucleotides against endogenous Cavβ [34, 62].

How does Cavβ enhance Ca2+ channel surface expression? An early hypothesis was that Cavβ shields or disrupts one or more ER retention signals on the I-II linker of Cavα1 [63]. However, several results are inconsistent with this hypothesis: (i) I-II linkers from several different Cavα1 subunits do not cause ER retention of CD8 or CD4 peptides [64-65], (ii) In the absence of Cavβ, transplanting the I-II linker of different HVA Cavα1 subunits (Cav2.2, Cav2.1 and Cav1.2) into a T-type channel (Cav3.1), which does not require Cavβ for its function, causes current upregulation instead of downregulation [45, 66], (iii) several labs implicated regions other than the I-II linker in Cavα1 trafficking [64, 67-71].

These inconsistencies prompted a re-evaluation of the mechanism of Cavβ-mediated upregulation of HVA channel expression. In a recent study [66], all of the L-type Cav1.2 channel intracellular linkers were systematically transplanted into the T-type channel, individually or in combination. This was followed by careful examination of the linkers’ ER-export and ER-retention properties, in the presence or absence of a Cavβ, by monitoring channel surface expression. The results suggest that the I-II linker of Cav1.2 has an ER export signal composed of 9 acidic residues downstream of the AID. All other intracellular linkers, including the N- and C-termini, were found to contain overall ER retention signals. Thus, it was proposed that the intracellular regions of Cavα1 form a complex that yields a prevailing ER retention signal, and when Cavβ binds to the I-II linker, it orchestrates a switch in the complex such that the ER export signal becomes dominant, enhancing Cavα1 surface expression. In this process, the Cavα1 C-terminus plays an essential role since it is absolutely required (but not sufficient) for Cavβ-dependent channel upregulation [66].

A few recent studies have proposed that Cavβ increases channel surface expression by preventing Cavα1 ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation [71-73]. In the absence of Cavβ, a proteasome inhibitor (MG132) can rescue Cavα1 surface expression. Cavβ coexpression, on the other hand, decreased Cav1.2 ubiquitination and association with proteins involved in proteasomal degradation, suggesting that Cavβ could be rerouting channels away from predestined proteasomal degradation. This mechanism was proposed for Cav2.2 channels [72]. However, Cav2.1 channels do not appear to be subject to this type of regulation [71]. For an extensive review on VGCC trafficking see [74].

3.3. Cavβ regulates Ca2+ channel gating

Besides enhancing channel surface expression, Cavβ regulates channel gating. Here we describe the effects of Cavβ on channel activation and voltage- and Ca2+-dependent inactivation. We also discuss a unifying model for the mechanism of Cavβ-mediated gating regulation. The effects of Cavβ on Ca2+ channel facilitation have been reviewed previously [7].

3.3.1 Cavβ enhances channel activation

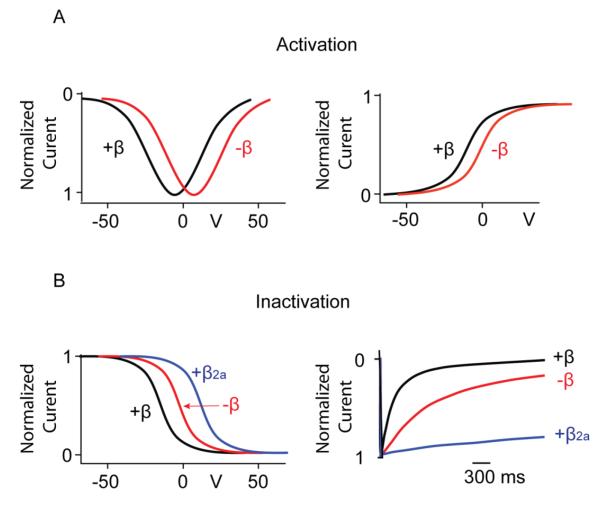

All Cavβs facilitate channel opening by shifting the voltage-dependence of channel activation by ~10-15 mV to more hyperpolarized voltages [75-77]. This is reflected as an increase in the open probability at the single channel level [78-79], with β2a producing the most dramatic increase in channel open probability [79-81]. Cavβ also often speeds channel activation [1, 82], which is observed as a shortened latency to first channel opening in single channel recordings [83-84]. Many of these effects can be reconstituted by the core region of Cavβ [12] and, in some cases, the GK domain alone [85].

3.3.2 Cavβ enhances inactivation, except β2a

Calcium channels inactivate in a voltage- and Ca2+-dependent manner (VDI and CDI respectively). This process is modulated by Cavβ in at least 3 ways: (1) Cavβ generally shifts the voltage-dependence of inactivation to more hyperpolarized voltages by ~10-20 mV (Fig. 3), enhancing VDI. Similarly, Cavβ increases CDI [86]. β2a, however, shifts the voltage-dependence of inactivation to more depolarized voltages by ~10 mV, reducing VDI [12, 87]. (2) Cavβ (except β2a) promotes Cav2 channels’ ‘closed state’ inactivation [88-89]. (3) Cavβ generally accelerates inactivation kinetics, but β2a and β2e decelerate inactivation kinetics (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Modulation of HVA Ca2+ channel gating by Cavβ. (A) Activation: Cavβ shifts the current-voltage curve (left panel) and the activation curve (right panel) to more hyperpolarized voltages. (B) Inactivation: Cavβ shifts the voltage dependence of inactivation to more hyperpolarized voltages, except β2a, which shifts it to more depolarized voltages (left panel). All Cavβ subunits speed the kinetics of inactivation, except β2a, which slows the kinetics of channel inactivation (right panel). All traces are schematic representations.

The unique effects of β2a on inactivation are largely due to its palmitoylation [90-91], but it seems that membrane anchorage rather than palmitoylation per se is critical [91-92]. Indeed, the non-palmitoylated but membrane-attached β2e has properties similar to β2a [49].

The molecular determinants on Cavβ that regulate channel inactivation are many. The N-terminus is clearly important, as indicated by the observation that natural β2 and β4 splice variants differing in their N-termini exhibit markedly different effects on VDI [49, 93-95]. The C-terminus, on the other hand, seems to play a limited or no role in regulating VDI [12, 96]. All Cavβ-GK domains, including that of β2a, speed VDI and hyperpolarize the voltage-dependence of VDI [12, 61, 97]. The HOOK domain is also important as swapping the HOOK between the core regions (SH3-HOOK-GK) of β1b and β2a also swaps their effects on VDI [12].

3.3.3. How does Cavβ regulate voltage-dependent activation and inactivation of HVA channels?

To answer this question, it is necessary to mention the molecular determinants of voltage-dependent activation (VDA) and inactivation (VDI) of VGCCs. For VDA, they include (i) the external pore and the ion selectivity filter formed by the pore loop between the S5 and S6 transmembrane segments of Cavα1 [98-101], (ii) the inner pore formed by all four S6 segments of Cavα1 [102], and (iii) the activation gate, located at the cytoplasmic end of the S6 segments [103].

The molecular determinants of VDI include the cytosolic ends of the S6 segments, the I-II linker – considered to be the inactivation gate, and the N- and C-termini of Cavα1 [for review, see 86, 104, 105].

Thus, the S6 segments are critical for both VDA and VDI. Notably, the AID, to which Cavβ binds, is connected to the IS6 segment through a short linker. Based on extensive studies [12, 18, 29, 35, 45, 55, 86, 106-107], a unified model for Cavβ regulation of VDA and VDI of VGCCs has emerged. First, when Cavβ is bound to the AID, the entire region starting with IS6 to the end of the AID becomes a continuous α-helix [18, 23, 45, 86]. This rigid structure allows Cavβ to regulate both activation and inactivation, most likely by changing the energetics of voltage-dependent movement of both IS6 and the inactivation gate. When the integrity of this rigid α-helix is disrupted by the insertion of glycine residues, the ability of Cavβ to regulate VDA, VDI and CDI are severely compromised, while Ca2+ channel surface expression remains unaffected [13, 86, 107]. These results underscore the essential role of a rigid IS6-AID linker in Cavβ regulation of VGCC gating. Further supporting this notion, the GK domain, which is the minimal part of Cavβ that can bind to the AID and presumably induce the formation of the rigid α-helix, can significantly impact (but not entirely normalize) activation and inactivation [12, 61, 97].

Second, and equally important for the model, the anchoring of Cavβ to Cavα1 through the AID-GK interaction enables the formation of intrinsically low-affinity interactions between Cavβ and other parts of Cavα1 that fully normalize channel gating [reviewed in 7].

An additional factor important for Cavβ regulation of gating is the orientation of Cavβ relative to Cavα1 [13, 107-108]. Insertions or deletions in the IS6-AID linker, which are expected to maintain the α-helical structure of the linker but induce a 180o rotation of Cavβ with respect to Cavα1, diminish Cavβ regulation of activation and inactivation [13, 107]. These studies are consistent with the notion that additional contacts between Cavβ and Cavα1 besides the AID-GK domain interaction are critical for VGCC gating.

4. Cavβ STOICHIOMETRY WITH Cavα1

4.1. Cavα1 and Cavβ are paired with a 1:1 stoichiometry

Early biochemical studies suggest that skeletal and neuronal VGCCs contain a single Cavα1 and a single Cavβ [109-110]. Extensive recent studies indicate that this is indeed the case and that the 1:1 stoichiometry is determined by the AID-GK domain interaction. (i) Covalently linked Cav1.2 and Cavβ2b (Cav1.2-Cavβ2b) have the same gating properties as channels formed by the coexpression of Cav1.2 and β2b. Moreover, when β2a, which slows inactivation, is coexpressed with Cav1.2-β2b, gating properties remain unchanged [111]. (ii) The simultaneous coexpression of β2a and β3 with Cavα1 yields two biophysically distinct channel populations, rather than a single population with intermediate biophysical properties [92, 112]. (iii) The crystal structures of the AID-Cavβ core complexes clearly show that each Cavβ binds a single AID [11, 18-19, 23], and mutations of key residues in the AID or the ABP abolish both Cavβ-mediated Ca2+ channel surface expression and gating modulation [4, 12-13, 39, 44].

4.2. Dimerization of Cavβ

Several recent studies suggested that Cavβ fragments can associate to form GK-GK [85, 113] or SH3-SH3 domain dimers [30]. While the molecular mechanism of GK-GK domain dimerization is unclear [113], SH3 domain dimerization seems to depend on a cysteine residue that participates in forming an SH3-SH3 domain disulfide bond [30].

In addition to fragment dimerization, full-length Cavβ dimerization and oligomerization has been proposed, including homodimerization for β3 and β2a, and heterodimerization between β3 and other Cavβs [30, 113]. Higher order Cavβ oligomers (3 or more Cavβs) have also been reported, based on limited data from co-immunoprecipitation and native gel analyses under reducing and non-reducing conditions [113]. The molecular mechanisms of full length Cavβ oligomerization are unknown. Mutating the cysteine that holds together the SH3 dimer disrupts SH3-SH3 dimerization but fails to prevent full length Cavβ2a from dimerizing [30]. Similarly, mutations that can individually disrupt GK fragment dimerization fail to prevent full-length Cavβ3 dimerization [113]. It is possible that both the GK and SH3 domains lend residues for Cavβ dimerization.

It was recently reported that Cavβ dimerization is critical for dynamin-mediated channel internalization [26, 30]. However, this was shown for Shaker K+ channels and Ca2+ channels with a deleted AID, while WT Cav1.2 channels prevent dynamin-mediated internalization. The steps in dynamin-mediate internalization are unclear but may involve the formation of a quaternary complex between two Cavβs and two dynamin molecules [30]. Interestingly, the formation of Cavβ dimers is suppressed in the presence of WT Cavα1 [30], consistent with a 1:1 stoichiometry of the Cavα1/Cavβ complex.

5. THE ROLE OF Cavβ IN Gβγ INHIBITION OF Cav2 CHANNELS

Cav2 channels are susceptible to several kinds of inhibition by hormones and neurotransmitters through the activation of G-protein coupled receptors (see Currie and Zamponi review in this issue). The most prominent type of inhibition is the membrane-delimited, voltage-dependent inhibition mediated by the direct binding of G protein Gβγ subunits to the channel’s α1 subunit [114-115].

5.1. Cavβ is required for voltage-dependent Gβγ inhibition

Many studies indicate that Cavβ is essential for Gβγ-dependent channel inhibition. In COS-7 cells, G protein inhibition of N-type Ca2+ channels was markedly enhanced by coexpressed Cavβs [116]; in tsA-201 cells, a point mutation in the AID of Cav2.2 (W391A) that disrupted Cavβ binding abolished voltage-dependent G protein inhibition [43]. In a recent study that directly tested whether Cavβ is required for Gβγ inhibition [13], large populations of Ca2+ channels devoid of Cavβ were obtained by washing away a mutant Cavβ that was loosely bound to the AID but was still able to chaperone channels to the membrane. Such β-less channels were still inhibited by purified Gβγ protein applied to the cytoplasmic side of the macropatch; however, all the hallmarks of voltage-dependent inhibition were absent [13, 117-118]. When Cavβ was supplied, Gβγ inhibition became voltage-dependent [13]. These results suggest that in the absence of Cavβ, Gβγ can bind the channel and inhibit it in a voltage-independent manner [13, 43]. They also suggest that under physiological conditions, Cavβ remains bound to the channel during Gβγ inhibition, enhancing the dissociation of Gβγ from the channels and giving rise to the voltage-dependence of inhibition [119]. There is further evidence supporting the notion that Cavβ remains associated with Cavα1 during Gβγ modulation. (1) Different Cavβs have different effects on voltage-dependent Gβγ inhibition, with β2a being the least effective in promoting this inhibition [61, 120-123]. In addition, the efficacy of the four Cavβs to increase the rate of Gβγ dissociation from the channel is different [121-122]. (2) VDA and VDI, which are significantly modulated by Cavβ, remain unchanged before, during, and after Gβγ modulation [13, 117, 123].

5.2. An allosteric model for the voltage-dependent G-protein inhibition of VGCC

An allosteric model was recently proposed for the origin of the voltage-dependence of Gβγ inhibition of Cav2 channels [13]. There are several components in this model. First, although the Gβγ-binding pocket in the holo-channel is still unknown, it is likely formed by several regions including the I-II linker, the N-terminus, and the C-terminus of Cavα1 [124]. Second, binding of Cavβ transforms IS6 and a large portion of the I-II linker, including the AID, into an α-helix. This allows movements in IS6, following a depolarization, to be efficiently transduced to dismantle the Gβγ binding pocket, causing Gβγ dissociation. In the absence of Cavβ, the AID is a random coil [18] and IS6 movements cannot be efficiently transmitted to the I-II linker. Thus, Gβγ stays on the channel, inhibiting it with no voltage dependence. Corroborating this model, mutations that disrupt the rigid α-helix encompassing IS6 and the AID, abolish the voltage dependence of Gβγ inhibition in the presence of Cavβ [13, 61].

5. ROLE OF Ca β IN THE REGULATION OF Ca2+ v CHANNELS BY PIP2 AND ARACHIDONIC ACID

5.1. β2a dampens the inhibitory effect of PIP2 depletion

Phosphatidylinositol-4, 5-biphosphate (PIP2),a membrane phospholipid composed of two long fatty acid chains attached to a phosphoinositol head group, is necessary for the maintenance of HVA currents [125-128], and PIP2 depletion following Gq-coupled receptor stimulation results in voltage-independent inhibition of HVA channels [92, 125, 129-130]. Recently, it was demonstrated that the coexpression of β2a with Cav2.1, Cav2.2 and Cav1.3 channels can largely prevent channel inhibition upon PIP2 depletion [92]. This effect was the direct result of β2a palmitoylation since preventing palmitoylation abolished channel protection from PIP2 depletion. Moreover, imparting palmitoylation to β3, by fusion to an unrelated palmitoylated peptide, enabled the modified β3 to protect the channels from PIP2 depletion [92]. The proposed molecular mechanism for β2a‘s action is that the two β2a palmitoyl groups, which are long fatty acid chains, can stabilize Ca2+ channels by substituting for PIP2. Although the PIP2 binding site on VGCCs is unknown, it was proposed to be ‘bidentate’ – one region binds the PIP2 fatty acid chains, and the other binds to the PIP2 head group. When both sites are occupied, the channel is ‘stretched’ in a more active conformation. It was further suggested that β2a can engage both sites to maintain channel activity even in the absence of PIP2 [92].

5.2. β2a suppresses channel inhibition by arachidonic acid

Many phospholipids, including PIP2, can be metabolized by lipases to arachidonic acid (AA), an unsaturated fatty acid without a head group. The accumulation of AA inhibits HVA Ca2+ channels [131-133]. It was recently suggested that this inhibition was the result of occupying only a single site within the bidentate lipid binding site on the channels [92]. The inhibitory action of AA on Cav1.3 is attenuated in the presence of β2a, but not other Cavβs [134-135]. This dampening effect critically depends on β2a palmitoylation per se, rather than membrane anchorage. Thus, the palmitoyl groups of β2a can both compete with AA to prevent VGCC inhibition, and also substitute for PIP2 and protect channels from PIP2 depletion, as discussed above. Both actions likely occur via the same bidentate lipid binding site on VGCCs [92, 134, 136]. Finally, the competition of the β2a palmitoyl groups with AA can be prevented by manipulating the IS6-AID linker to change the orientation of Cavβ in relation to Cavα1 [108], suggesting that β2a palmitoyl groups have a precise binding site on the channel, likely the same site where PIP2 and AA bind.

6. Cavβ MAY HAVE TRANSCRIPTIONAL ACTIVITY

Several short Cavβ isoforms have been cloned that do not contain a GK domain [83, 137-140]. In the first such report, a short Cavβ that lacks 90% of the GK domain and the entire C-terminus was cloned form chicken brain and named β4c [140]. This cβ4c has almost no effect on Cav2.1 channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes but it can dose-dependently attenuate the repressor function of heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1), a chromatin organizer. These findings suggest that cβ4c may function as a transcription regulator. Similar results have been recently reported for a human β4c isoform found in the nuclei of vestibular neurons [141]. Full length Cavβ has also been implicated in transcriptional regulation. β3, for example, can directly interact with and suppress the transcriptional activity of Pax6(S), in vitro [142]. In HEK 293T cells, coexpression of β3 and Pax6(S) results in the translocation of β3 from the cytoplasm to the nucleus. Several other studies have shown nuclear targeting of Cavβ in native cells [79, 143-144]. It remains to be determined which specific genes are the targets of Cavβ transcriptional regulation. It is also unclear whether nuclear targeting of Cavβ is correlated with VGCC activity; one recent study suggests that L-type Ca2+ channel activity diminishes the nuclear targeting of β4b in the cerebellum [143].

7. Cavβ knockouts and pathophysiology

Because of the essential role of Cavβ to enable the surface expression and functional modulation of HVA Ca2+ channels, Cavβ mutations have been implicated in human disease. Cavβ knockout animals and mutants have severe phenotypes that are in some cases lethal. Ultimately, what determines the phenotypical outcome of a knockout mouse is the ability of the remaining Cavβs to compensate for the lost functions.

7.1. β1

Cavβ1 is expressed in brain, heart, skeletal muscle, spleen, T-cells and other tissues [reviewed in 7]. The β1a isoform, however, is exclusively expressed in skeletal muscle where it partners with skeletal muscle Cav1.1, and is irreplaceable for excitation-contraction coupling. Thus, β1 knockout mice, similar to Cav1.1 knockouts, are born motionless and die immediately from asphyxiation [75]. A similar phenotype is observed in zebrafish [145].

Paradoxically, the increased expression of β1a in aging mice was recently proposed to cause skeletal muscle weakness due to decreased levels of Cav1.1 channel expression [146]. Knockdown of β1 in aging mice could increase muscle force and Cav1.1 expression levels to those observed in young mice. This is a surprising effect considering Cavβ normally enhances VGCC expression, as is the case in young mice [146]. It remains to be determined what age-related factors turn Cavβ from a positive to a negative regulator of Cav1.1 expression.

7.2. β2

Cavβ2 and its various splice variants are expressed in brain, heart, lung, nerve endings at the neuro-muscular junction, T-cells, osteoblasts and other tissues [7]. It is also the predominant Cavβ in the heart, especially Cavβ2b [79]. β2 knockouts die prenatally at embryonic day 10.5 due to lack of cardiac contractions [147-148]. Interestingly, when β2 expression is restored to the heart of β2-knockout animals using a cardiac muscle-specific promoter, the animals survive but are deaf due to several deficiencies in the inner ear, including a dramatic reduction in the expression of Cav1.3 channels [147, 149]. These ‘rescued’ mice also have defects in vision with a phenotype similar to human patients with congenital stationary night blindness [150].

It is not clear whether β2 is essential only during certain stages of development or throughout life. A recent study in which the β2 gene was conditionally knocked out in adult mouse cardiomyocytes gave unanticipated results [151]. Peak calcium currents were reduced by only ~ 30% and the mice had no obvious impairment, suggesting that β2 may be more critical for the developing than the adult heart [151].

Two point mutations in β2b have been implicated in cardiovascular human diseases. The S481L mutation, which occurs in the C-terminus of β2b, contributes to a type of sudden death syndrome characterized by a short QT interval and an elevated ST-segment [152]. The other mutation, in the β2b N-terminus (T11I), causes accelerated inactivation of cardiac L-type channels and is linked to the Brugada syndrome [153].

7.3. β3

Cavβ3 knockouts are viable [154-155], with reduced perception of inflammatory pain but unaltered mechanically or thermally induced pain. This is likely the result of reduced N-type calcium channel expression in dorsal root ganglia [77]. Cavβ3 knockouts also have abnormally high insulin secretion at high blood glucose concentrations [156]. A high salt diet causes abnormally elevated blood pressure, a reduction in plasma catecholamine levels, and a hypertrophy of heart and aortic smooth muscle [155, 157]. These results point to a compromised sympathetic control in β3 knockout mice, likely due to reduced N- and L-type channel activity [154]. Behaviorally, β3-null mice exhibit impaired working memory, but some forms of hippocampus-dependent learning are enhanced [158-159]. Knockout mice also have lower anxiety, increased aggression, and increased nighttime activity [159]. Finally, both β3 and β4 knockout mice have abnormal T-cell signaling, revealing an unanticipated function of Cavβs in the immune system [160].

A recent study comparing epileptic patients with non-epileptic individuals identified 3 mutations in β3 that were present only in patients; however, it is difficult to conclude whether these mutations are the cause of epilepsy [161].

7.4. β4

Lethargic mice are naturally occurring β4 knockouts [162-164]. They have an insertion that causes exon skipping and a premature stop codon in the gene for β4. These mice exhibit ataxia, seizures, absence epilepsy, and paroxysmal dyskinesia [162, 165-166]. Some of this phenotype is contributed by a 50% upregulation of T-type Ca2+ channels in thalamic neurons [167]. Other characteristics of lethargic mice include reduced excitatory neurotransmission in the thalamus [168] and a modified electro-oculogram [169]. Interestingly, and perhaps indicative of Cavβ functions that are independent of VGCC, β4 knockouts have aberrant splenic and thymic involution [163-164] and renal cysts [163]. Similar to β3 knockouts, CD4+ T-cells have attenuated receptor-mediated Ca2+ responses [160].

In humans, an R468Q mutation in the gene encoding β4 is associated with a history of febrile seizures, presumably due to the enhancement of Cav2.1 currents [170]. In addition, a juvenile myoclonic epilepsy patient was found to have a truncated β4 (R482x) [171]. Interestingly, two families with different disease histories - one with episodic ataxia and the other with generalized epilepsy and praxis-induced seizures - share the same mutation in β4 (C104F) [171], highlighting the importance of genetic background in disease penetrance.

8. FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Past studies have provided great insights into the structure, function, and physiology of Cavβ. They have also opened new avenues for future research and prompted many intriguing questions that remain to be answered, some of which we highlight below.

Knockout mice provide a useful tool in the study of Cavβ physiology. Conditional and tissue-specific knockouts are particularly useful as they circumvent compensatory mechanisms that are triggered in conventional knockout mice. This advantage was highlighted in several recent studies that found unexpected mouse phenotypes when Cavβ was conditionally knocked out [147, 150-151]. We anticipate that future conditional knockouts would similarly provide great insights into the physiological functions of Cavβ and the significance of its diversity.

Cavβ has functions that are independent of VGCC [reviewed in 7]. Most notable is a possible role in transcriptional regulation, which has been demonstrated for both short splice variants and full-length Cavβ. It is not clear, however, how and which tissues benefit from such regulation under physiological conditions. It would also be interesting to know which signaling events trigger the nuclear translocation of Cavβ.

There are currently two prevalent hypothesis that explain the role of Cavβ in VGCC trafficking: (1) Cavβ alters the balance of ER retention and ER export signals on Cavα1 in favor of the latter, and (2) Cavβ protects channels from predestined proteasomal degradation. These two hypotheses are not mutually exclusive but their relationship remains unclear. It also remains to be determined whether the proposed mechanisms of Cavβ-mediated channel trafficking apply to all Cav1 and Cav2 channels.

The crystal structures of the Cavβ core have provided great insights into the molecular mechanisms of Cavβ function. It would be of great interest to obtain high-resolution structures of full length Cavβ and of Cavβ in complex with its various interacting partners, such as RGK proteins, dynamin or the ryanodine receptor. Such structures would shed significant light on how different cellular signals converge on Cavβ to regulate VGCC function.

Cavβs have many interacting partners (Fig. 2, also reviewed in [7]), some of which significantly impact the function of VGCCs. The recent findings that Cavβ interacts with synaptic proteins [172-173] uncover new roles for Cavβ in the organization of the synaptic vesicle release machinery and reveal a new facet of VGCC physiology. We anticipate that the search and study of new Cavβ partners will continue to be an interesting and productive area of research in the future.

Highlights.

The Ca2+ channel β subunit is required for voltage-gated Ca2+ channel function.

We review the structure and many functions of Cavβ

Ca β also has functions independent of Ca2+ v channels

Cavβ knockouts have severe defficienceis and Cavβ is implicated in human disease.

We provide a perspective for future research in this field.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Lacerda AE, Kim HS, Ruth P, Perez-Reyes E, Flockerzi V, Hofmann F, Birnbaumer L, Brown AM. Normalization of current kinetics by interaction between the alpha 1 and beta subunits of the skeletal muscle dihydropyridine-sensitive Ca2+ channel. Nature. 1991;352:527–530. doi: 10.1038/352527a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Curtis BM, Catterall WA. Purification of the calcium antagonist receptor of the voltage-sensitive calcium channel from skeletal muscle transverse tubules. Biochemistry. 1984;23:2113–2118. doi: 10.1021/bi00305a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Ruth P, Rohrkasten A, Biel M, Bosse E, Regulla S, Meyer HE, Flockerzi V, Hofmann F. Primary structure of the beta subunit of the DHP-sensitive calcium channel from skeletal muscle. Science. 1989;245:1115–1118. doi: 10.1126/science.2549640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Pragnell M, De Waard M, Mori Y, Tanabe T, Snutch TP, Campbell KP. Calcium channel beta-subunit binds to a conserved motif in the I-II cytoplasmic linker of the alpha 1-subunit. Nature. 1994;368:67–70. doi: 10.1038/368067a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Waard M. De, Witcher DR, Pragnell M, Liu H, Campbell KP. Properties of the alpha 1-beta anchoring site in voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:12056–12064. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.20.12056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Witcher DR, De Waard M, Liu H, Pragnell M, Campbell KP. Association of native Ca2+ channel beta subunits with the alpha 1 subunit interaction domain. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:18088–18093. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.30.18088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Buraei Z, Yang J. The β subunit of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Physiological reviews. 2010;90:1461–1506. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00057.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].De Waard M, Pragnell M, Campbell KP. Ca2+ channel regulation by a conserved beta subunit domain. Neuron. 1994;13:495–503. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90363-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Birnbaumer L, Qin N, Olcese R, Tareilus E, Platano D, Costantin J, Stefani E. Structures and functions of calcium channel beta subunits. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1998;30:357–375. doi: 10.1023/a:1021989622656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Hanlon MR, Berrow NS, Dolphin AC, Wallace BA. Modelling of a voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel beta subunit as a basis for understanding its functional properties. FEBS Lett. 1999;445:366–370. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00156-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Chen YH, Li MH, Zhang Y, He LL, Yamada Y, Fitzmaurice A, Shen Y, Zhang H, Tong L, Yang J. Structural basis of the alpha1-beta subunit interaction of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Nature. 2004;429:675–680. doi: 10.1038/nature02641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].He LL, Zhang Y, Chen YH, Yamada Y, Yang J. Functional modularity of the beta-subunit of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Biophys J. 2007;93:834–845. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.101691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Zhang Y, Chen YH, Bangaru SD, He L, Abele K, Tanabe S, Kozasa T, Yang J. Origin of the voltage dependence of G-protein regulation of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels. J Neurosci. 2008;28:14176–14188. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1350-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Chen YH, He LL, Buchanan DR, Zhang Y, Fitzmaurice A, Yang J. Functional dissection of the intramolecular Src homology 3-guanylate kinase domain coupling in voltage-gated Ca2+ channel beta-subunits. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:1969–1975. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Opatowsky Y, Chomsky-Hecht O, Kang MG, Campbell KP, Hirsch JA. The voltage-dependent calcium channel beta subunit contains two stable interacting domains. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:52323–52332. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303564200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Gao T, Chien AJ, Hosey MM. Complexes of the alpha1C and beta subunits generate the necessary signal for membrane targeting of class C L-type calcium channels. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:2137–2144. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.4.2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].McGee AW, Nunziato DA, Maltez JM, Prehoda KE, Pitt GS, Bredt DS. Calcium channel function regulated by the SH3-GK module in beta subunits. Neuron. 2004;42:89–99. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00149-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Opatowsky Y, Chen CC, Campbell KP, Hirsch JA. Structural analysis of the voltage-dependent calcium channel beta subunit functional core and its complex with the alpha 1 interaction domain. Neuron. 2004;42:387–399. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00250-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Van Petegem F, Clark KA, Chatelain FC, Minor DL., Jr. Structure of a complex between a voltage-gated calcium channel beta-subunit and an alpha-subunit domain. Nature. 2004;429:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nature02588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Vendel AC, Rithner CD, Lyons BA, Horne WA. Solution structure of the N-terminal A domain of the human voltage-gated Ca2+channel beta4a subunit. Protein Sci. 2006;15:378–383. doi: 10.1110/ps.051894506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Stehle T, Schulz GE. Three-dimensional structure of the complex of guanylate kinase from yeast with its substrate GMP. J Mol Biol. 1990;211:249–254. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90024-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Blaszczyk J, Li Y, Yan H, Ji X. Crystal structure of unligated guanylate kinase from yeast reveals GMP-induced conformational changes. J Mol Biol. 2001;307:247–257. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Almagor L, Chomsky-Hecht O, Ben-Mocha A, Hendin-Barak D, Dascal N, Hirsch JA. The role of a voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel intracellular linker: a structure-function analysis. J Neurosci. 2012;32:7602–7613. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5727-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Zou S, Jha S, Kim EY, Dryer SE. The beta 1 subunit of L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels independently binds to and inhibits the gating of large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels. Molecular pharmacology. 2008;73:369–378. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.040733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Larson SM, Davidson AR. The identification of conserved interactions within the SH3 domain by alignment of sequences and structures. Protein Sci. 2000;9:2170–2180. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.11.2170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Gonzalez-Gutierrez G, Miranda-Laferte E, Neely A, Hidalgo P. The Src homology 3 domain of the beta-subunit of voltage-gated calcium channels promotes endocytosis via dynamin interaction. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:2156–2162. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609071200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Takahashi SX, Miriyala J, Colecraft HM. Membrane-associated guanylate kinase-like properties of beta-subunits required for modulation of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:7193–7198. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306665101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Takahashi SX, Miriyala J, Tay LH, Yue DT, Colecraft HM. A CaVbeta SH3/guanylate kinase domain interaction regulates multiple properties of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. J Gen Physiol. 2005;126:365–377. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Maltez JM, Nunziato DA, Kim J, Pitt GS. Essential Ca(V)beta modulatory properties are AID-independent. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:372–377. doi: 10.1038/nsmb909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Miranda-Laferte E, Gonzalez-Gutierrez G, Schmidt S, Zeug A, Ponimaskin EG, Neely A, Hidalgo P. Homodimerization of the Src homology 3 domain of the calcium channel beta-subunit drives dynamin-dependent endocytosis. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:22203–22210. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.201871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].De Waard M, Scott VE, Pragnell M, Campbell KP. Identification of critical amino acids involved in alpha1-beta interaction in voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels. FEBS Lett. 1996;380:272–276. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Scott VE, De Waard M, Liu H, Gurnett CA, Venzke DP, Lennon VA, Campbell KP. Beta subunit heterogeneity in N-type Ca2+ channels. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:3207–3212. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.6.3207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Geib S, Sandoz G, Mabrouk K, Matavel A, Marchot P, Hoshi T, Villaz M, Ronjat M, Miquelis R, Leveque C, de Waard M. Use of a purified and functional recombinant calcium-channel beta4 subunit in surface-plasmon resonance studies. Biochem J. 2002;364:285–292. doi: 10.1042/bj3640285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Canti C, Davies A, Berrow NS, Butcher AJ, Page KM, Dolphin AC. Evidence for two concentration-dependent processes for beta-subunit effects on alpha1B calcium channels. Biophys J. 2001;81:1439–1451. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75799-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Van Petegem F, Duderstadt KE, Clark KA, Wang M, Minor DL., Jr. Alanine-scanning mutagenesis defines a conserved energetic hotspot in the CaValpha1 AID-CaVbeta interaction site that is critical for channel modulation. Structure. 2008;16:280–294. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Butcher AJ, Leroy J, Richards MW, Pratt WS, Dolphin AC. The importance of occupancy rather than affinity of CaV(beta) subunits for the calcium channel I-II linker in relation to calcium channel function. J Physiol. 2006;574:387–398. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.109744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Bell DC, Butcher AJ, Berrow NS, Page KM, Brust PF, Nesterova A, Stauderman KA, Seabrook GR, Nurnberg B, Dolphin AC. Biophysical properties, pharmacology, and modulation of human, neuronal L-type (alpha(1D), Ca(V)1.3) voltage-dependent calcium currents. Journal of neurophysiology. 2001;85:816–827. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.2.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Richards MW, Butcher AJ, Dolphin AC. Ca2+ channel beta-subunits: structural insights AID our understanding. Trends in pharmacological sciences. 2004;25:626–632. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Berrou L, Dodier Y, Raybaud A, Tousignant A, Dafi O, Pelletier JN, Parent L. The C-terminal residues in the alpha-interacting domain (AID) helix anchor CaV beta subunit interaction and modulation of CaV2.3 channels. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:494–505. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410859200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Berrou L, Klein H, Bernatchez G, Parent L. A specific tryptophan in the I-II linker is a key determinant of beta-subunit binding and modulation in Ca(V)2.3 calcium channels. Biophys J. 2002;83:1429–1442. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)73914-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Hidalgo P, Gonzalez-Gutierrez G, Garcia-Olivares J, Neely A. The alpha1-beta-subunit interaction that modulates calcium channel activity is reversible and requires a competent alpha-interaction domain. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:24104–24110. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605930200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Gerster U, Neuhuber B, Groschner K, Striessnig J, Flucher BE. Current modulation and membrane targeting of the calcium channel alpha1C subunit are independent functions of the beta subunit. J Physiol. 1999;517(Pt 2):353–368. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0353t.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Leroy J, Richards MW, Butcher AJ, Nieto-Rostro M, Pratt WS, Davies A, Dolphin AC. Interaction via a key tryptophan in the I-II linker of N-type calcium channels is required for beta1 but not for palmitoylated beta2, implicating an additional binding site in the regulation of channel voltage-dependent properties. J Neurosci. 2005;25:6984–6996. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1137-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Gonzalez-Gutierrez G, Miranda-Laferte E, Naranjo D, Hidalgo P, Neely A. Mutations of nonconserved residues within the calcium channel alpha1-interaction domain inhibit beta-subunit potentiation. J Gen Physiol. 2008;132:383–395. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Arias JM, Murbartian J, Vitko I, Lee JH, Perez-Reyes E. Transfer of beta subunit regulation from high to low voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:3907–3912. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Perez-Reyes E, Castellano A, Kim HS, Bertrand P, Baggstrom E, Lacerda AE, Wei XY, Birnbaumer L. Cloning and expression of a cardiac/brain beta subunit of the L-type calcium channel. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:1792–1797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Obermair GJ, Schlick B, Di Biase V, Subramanyam P, Gebhart M, Baumgartner S, Flucher BE. Reciprocal interactions regulate targeting of calcium channel beta subunits and membrane expression of alpha1 subunits in cultured hippocampal neurons. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:5776–5791. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.044271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Bogdanov Y, Brice NL, Canti C, Page KM, Li M, Volsen SG, Dolphin AC. Acidic motif responsible for plasma membrane association of the voltage-dependent calcium channel beta1b subunit. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:894–902. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Takahashi SX, Mittman S, Colecraft HM. Distinctive modulatory effects of five human auxiliary beta2 subunit splice variants on L-type calcium channel gating. Biophys J. 2003;84:3007–3021. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)70027-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Chien AJ, Carr KM, Shirokov RE, Rios E, Hosey MM. Identification of palmitoylation sites within the L-type calcium channel beta2a subunit and effects on channel function. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:26465–26468. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.43.26465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Chien AJ, Gao T, Perez-Reyes E, Hosey MM. Membrane targeting of L-type calcium channels. Role of palmitoylation in the subcellular localization of the beta2a subunit. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:23590–23597. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.36.23590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Hurley JH, Cahill AL, Currie KP, Fox AP. The role of dynamic palmitoylation in Ca2+ channel inactivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:9293–9298. doi: 10.1073/pnas.160589697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Washbourne P. Greasing transmission: palmitoylation at the synapse. Neuron. 2004;44:901–902. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Arikkath J, Campbell KP. Auxiliary subunits: essential components of the voltage-gated calcium channel complex. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2003;13:298–307. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(03)00066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Dolphin AC. Beta subunits of voltage-gated calcium channels. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2003;35:599–620. doi: 10.1023/b:jobb.0000008026.37790.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Jarvis SE, Zamponi GW. Trafficking and regulation of neuronal voltage-gated calcium channels. Current opinion in cell biology. 2007;19:474–482. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Zamponi GW. Voltage-gated calcium channels. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; Georgetown, Tex. New York, N.Y.: 2005. Landes Bioscience/Eurekah.com. [Google Scholar]

- [58].Wei SK, Colecraft HM, DeMaria CD, Peterson BZ, Zhang R, Kohout TA, Rogers TB, Yue DT. Ca(2+) channel modulation by recombinant auxiliary beta subunits expressed in young adult heart cells. Circulation research. 2000;86:175–184. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.2.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Berrow NS, Campbell V, Fitzgerald EM, Brickley K, Dolphin AC. Antisense depletion of beta-subunits modulates the biophysical and pharmacological properties of neuronal calcium channels. J Physiol. 1995;482(Pt 3):481–491. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Leuranguer V, Bourinet E, Lory P, Nargeot J. Antisense depletion of beta-subunits fails to affect T-type calcium channels properties in a neuroblastoma cell line. Neuropharmacology. 1998;37:701–708. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(98)00060-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Dresviannikov AV, Page KM, Leroy J, Pratt WS, Dolphin AC. Determinants of the voltage dependence of G protein modulation within calcium channel beta subunits. Pflugers Arch. 2009;457:743–756. doi: 10.1007/s00424-008-0549-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Tareilus E, Roux M, Qin N, Olcese R, Zhou J, Stefani E, Birnbaumer L. A Xenopus oocyte beta subunit: evidence for a role in the assembly/expression of voltage-gated calcium channels that is separate from its role as a regulatory subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:1703–1708. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Bichet D, Cornet V, Geib S, Carlier E, Volsen S, Hoshi T, Mori Y, De Waard M. The I-II loop of the Ca2+ channel alpha1 subunit contains an endoplasmic reticulum retention signal antagonized by the beta subunit. Neuron. 2000;25:177–190. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80881-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Cornet V, Bichet D, Sandoz G, Marty I, Brocard J, Bourinet E, Mori Y, Villaz M, De Waard M. Multiple determinants in voltage-dependent P/Q calcium channels control their retention in the endoplasmic reticulum. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;16:883–895. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Altier C, Garcia-Caballero A, Simms B, Walcher J, Tedford HW, Hermosilla G, Zamponi GW. The Cav beta subunit prevents Nedd4 mediated ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of L-type calcium channels via the Derlin-1/p97 ERAD protein complex in: SFN 2009, vol. Poster#: 519.13/D6. Chicago, Ill.: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [66].Fang K, Colecraft HM. Mechanism of auxiliary beta-subunit-mediated membrane targeting of L-type (Ca(V)1.2) channels. J Physiol. 2011;589:4437–4455. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.214247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Flucher BE, Kasielke N, Grabner M. The triad targeting signal of the skeletal muscle calcium channel is localized in the COOH terminus of the alpha(1S) subunit. The Journal of cell biology. 2000;151:467–478. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.2.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Wei X, Neely A, Olcese R, Lang W, Stefani E, Birnbaumer L. Increase in Ca2+ channel expression by deletions at the amino terminus of the cardiac alpha 1C subunit. Receptors & channels. 1996;4:205–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Kobrinsky E, Tiwari S, Maltsev VA, Harry JB, Lakatta E, Abernethy DR, Soldatov NM. Differential role of the alpha1C subunit tails in regulation of the Cav1.2 channel by membrane potential, beta subunits, and Ca2+ ions. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:12474–12485. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412140200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Gao T, Bunemann M, Gerhardstein BL, Ma H, Hosey MM. Role of the C terminus of the alpha 1C (CaV1.2) subunit in membrane targeting of cardiac L-type calcium channels. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:25436–25444. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003465200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Altier C, Garcia-Caballero A, Simms B, You H, Chen L, Walcher J, Tedford HW, Hermosilla T, Zamponi GW. The Cavbeta subunit prevents RFP2-mediated ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of L-type channels. Nature neuroscience. 2011;14:173–180. doi: 10.1038/nn.2712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Waithe D, Ferron L, Page KM, Chaggar K, Dolphin AC. Beta-subunits promote the expression of Ca(V)2.2 channels by reducing their proteasomal degradation. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:9598–9611. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.195909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Rougier JS, Albesa M, Abriel H, Viard P. Neuronal precursor cell-expressed developmentally down-regulated 4-1 (NEDD4-1) controls the sorting of newly synthesized Ca(V)1.2 calcium channels. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:8829–8838. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.166520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Simms BA, Zamponi GW. Trafficking and stability of voltage-gated calcium channels. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012;69:843–856. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0843-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Gregg RG, Messing A, Strube C, Beurg M, Moss R, Behan M, Sukhareva M, Haynes S, Powell JA, Coronado R, Powers PA. Absence of the beta subunit (cchb1) of the skeletal muscle dihydropyridine receptor alters expression of the alpha 1 subunit and eliminates excitation-contraction coupling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:13961–13966. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Weissgerber P, Held B, Bloch W, Kaestner L, Chien KR, Fleischmann BK, Lipp P, Flockerzi V, Freichel M. Reduced cardiac L-type Ca2+ current in Ca(V)beta2−/− embryos impairs cardiac development and contraction with secondary defects in vascular maturation. Circulation research. 2006;99:749–757. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000243978.15182.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Murakami M, Fleischmann B, De Felipe C, Freichel M, Trost C, Ludwig A, Wissenbach U, Schwegler H, Hofmann F, Hescheler J, Flockerzi V, Cavalie A. Pain perception in mice lacking the beta3 subunit of voltage-activated calcium channels. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:40342–40351. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203425200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Wakamori M, Mikala G, Mori Y. Auxiliary subunits operate as a molecular switch in determining gating behaviour of the unitary N-type Ca2+ channel current in Xenopus oocytes. J Physiol. 1999;517(Pt 3):659–672. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0659s.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Colecraft HM, Alseikhan B, Takahashi SX, Chaudhuri D, Mittman S, Yegnasubramanian V, Alvania RS, Johns DC, Marban E, Yue DT. Novel functional properties of Ca(2+) channel beta subunits revealed by their expression in adult rat heart cells. J Physiol. 2002;541:435–452. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.018515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Cens T, Restituito S, Galas S, Charnet P. Voltage and calcium use the same molecular determinants to inactivate calcium channels. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:5483–5490. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.9.5483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Dzhura I, Neely A. Differential modulation of cardiac Ca2+ channel gating by beta-subunits. Biophys J. 2003;85:274–289. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74473-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Stea A, Dubel SJ, Pragnell M, Leonard JP, Campbell KP, Snutch TP. A beta-subunit normalizes the electrophysiological properties of a cloned N-type Ca2+ channel alpha 1-subunit. Neuropharmacology. 1993;32:1103–1116. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(93)90005-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Hullin R, Khan IF, Wirtz S, Mohacsi P, Varadi G, Schwartz A, Herzig S. Cardiac L-type calcium channel beta-subunits expressed in human heart have differential effects on single channel characteristics. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:21623–21630. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211164200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Luvisetto S, Fellin T, Spagnolo M, Hivert B, Brust PF, Harpold MM, Stauderman KA, Williams ME, Pietrobon D. Modal gating of human CaV2.1 (P/Q-type) calcium channels: I. The slow and the fast gating modes and their modulation by beta subunits. J Gen Physiol. 2004;124:445–461. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200409034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Gonzalez-Gutierrez G, Miranda-Laferte E, Nothmann D, Schmidt S, Neely A, Hidalgo P. The guanylate kinase domain of the beta-subunit of voltage-gated calcium channels suffices to modulate gating. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:14198–14203. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806558105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Findeisen F, Minor DL., Jr. Disruption of the IS6-AID linker affects voltage-gated calcium channel inactivation and facilitation. J Gen Physiol. 2009;133:327–343. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200810143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Olcese R, Qin N, Schneider T, Neely A, Wei X, Stefani E, Birnbaumer L. The amino terminus of a calcium channel beta subunit sets rates of channel inactivation independently of the subunit’s effect on activation. Neuron. 1994;13:1433–1438. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90428-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Patil PG, Brody DL, Yue DT. Preferential closed-state inactivation of neuronal calcium channels. Neuron. 1998;20:1027–1038. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80483-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Yasuda T, Lewis RJ, Adams DJ. Overexpressed Ca(v)beta3 inhibits N-type (Cav2.2) calcium channel currents through a hyperpolarizing shift of ultra-slow and closed-state inactivation. J Gen Physiol. 2004;123:401–416. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200308967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Qin N, Platano D, Olcese R, Costantin JL, Stefani E, Birnbaumer L. Unique regulatory properties of the type 2a Ca2+ channel beta subunit caused by palmitoylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:4690–4695. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Restituito S, Cens T, Barrere C, Geib S, Galas S, De Waard M, Charnet P. The [beta] 2a subunit is a molecular groom for the Ca2+ channel inactivation gate. J Neurosci. 2000;20:9046–9052. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-24-09046.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Suh BC, Kim DI, Falkenburger BH, Hille B. Membrane-localized beta-subunits alter the PIP2 regulation of high-voltage activated Ca2+ channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:3161–3166. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121434109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Helton TD, Horne WA. Alternative splicing of the beta 4 subunit has alpha1 subunit subtype-specific effects on Ca2+ channel gating. J Neurosci. 2002;22:1573–1582. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-05-01573.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Helton TD, Kojetin DJ, Cavanagh J, Horne WA. Alternative splicing of a beta4 subunit proline-rich motif regulates voltage-dependent gating and toxin block of Cav2.1 Ca2+ channels. J Neurosci. 2002;22:9331–9339. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-21-09331.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Herzig S, Khan IF, Grundemann D, Matthes J, Ludwig A, Michels G, Hoppe UC, Chaudhuri D, Schwartz A, Yue DT, Hullin R. Mechanism of Ca(v)1.2 channel modulation by the amino terminus of cardiac beta2-subunits. FASEB J. 2007;21:1527–1538. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7377com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Stotz SC, Barr W, McRory JE, Chen L, Jarvis SE, Zamponi GW. Several structural domains contribute to the regulation of N-type calcium channel inactivation by the beta 3 subunit. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:3793–3800. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308991200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Richards MW, Leroy J, Pratt WS, Dolphin AC. The HOOK-domain between the SH3 and the GK domains of Cavbeta subunits contains key determinants controlling calcium channel inactivation. Channels (Austin) 2007;1:92–101. doi: 10.4161/chan.4145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Kim MS, Morii T, Sun LX, Imoto K, Mori Y. Structural determinants of ion selectivity in brain calcium channel. FEBS Lett. 1993;318:145–148. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80009-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Yang J, Ellinor PT, Sather WA, Zhang JF, Tsien RW. Molecular determinants of Ca2+ selectivity and ion permeation in L-type Ca2+ channels. Nature. 1993;366:158–161. doi: 10.1038/366158a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Kuo CC, Hess P. Ion permeation through the L-type Ca2+ channel in rat phaeochromocytoma cells: two sets of ion binding sites in the pore. J Physiol. 1993;466:629–655. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Sather WA, McCleskey EW. Permeation and selectivity in calcium channels. Annu Rev Physiol. 2003;65:133–159. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.65.092101.142345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Zhen XG, Xie C, Fitzmaurice A, Schoonover CE, Orenstein ET, Yang J. Functional architecture of the inner pore of a voltage-gated Ca2+ channel. J Gen Physiol. 2005;126:193–204. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Xie C, Zhen XG, Yang J. Localization of the activation gate of a voltage-gated Ca2+ channel. J Gen Physiol. 2005;126:205–212. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Hering S, Berjukow S, Sokolov S, Marksteiner R, Weiss RG, Kraus R, Timin EN. Molecular determinants of inactivation in voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. J Physiol. 2000;528(Pt 2):237–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00237.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Stotz SC, Jarvis SE, Zamponi GW. Functional roles of cytoplasmic loops and pore lining transmembrane helices in the voltage-dependent inactivation of HVA calcium channels. J Physiol. 2004;554:263–273. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.047068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Walker D, Bichet D, Geib S, Mori E, Cornet V, Snutch TP, Mori Y, De Waard M. A new beta subtype-specific interaction in alpha1A subunit controls P/Q-type Ca2+ channel activation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:12383–12390. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.18.12383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Vitko I, Shcheglovitov A, Baumgart JP, Arias O, II, Murbartian J, Arias JM, Perez-Reyes E. Orientation of the calcium channel beta relative to the alpha(1)2.2 subunit is critical for its regulation of channel activity. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3560. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Mitra-Ganguli T, Vitko I, Perez-Reyes E, Rittenhouse AR. Orientation of palmitoylated CaVbeta2a relative to CaV2.2 is critical for slow pathway modulation of N-type Ca2+ current by tachykinin receptor activation. J Gen Physiol. 2009;134:385–396. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200910204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Witcher DR, De Waard M, Sakamoto J, Franzini-Armstrong C, Pragnell M, Kahl SD, Campbell KP. Subunit identification and reconstitution of the N-type Ca2+ channel complex purified from brain. Science. 1993;261:486–489. doi: 10.1126/science.8392754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Takahashi M, Seagar MJ, Jones JF, Reber BF, Catterall WA. Subunit structure of dihydropyridine-sensitive calcium channels from skeletal muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:5478–5482. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.15.5478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Dalton S, Takahashi SX, Miriyala J, Colecraft HM. A single CaVbeta can reconstitute both trafficking and macroscopic conductance of voltage-dependent calcium channels. J Physiol. 2005;567:757–769. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.093195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Jones LP, Wei SK, Yue DT. Mechanism of auxiliary subunit modulation of neuronal alpha1E calcium channels. J Gen Physiol. 1998;112:125–143. doi: 10.1085/jgp.112.2.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Lao QZ, Kobrinsky E, Liu Z, Soldatov NM. Oligomerization of Cavbeta subunits is an essential correlate of Ca2+ channel activity. FASEB J. 2010;24:5013–5023. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-165381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Herlitze S, Garcia DE, Mackie K, Hille B, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Modulation of Ca2+ channels by G-protein beta gamma subunits. Nature. 1996;380:258–262. doi: 10.1038/380258a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Ikeda SR. Voltage-dependent modulation of N-type calcium channels by G-protein beta gamma subunits. Nature. 1996;380:255–258. doi: 10.1038/380255a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].Meir A, Bell DC, Stephens GJ, Page KM, Dolphin AC. Calcium channel beta subunit promotes voltage-dependent modulation of alpha 1 B by G beta gamma. Biophys J. 2000;79:731–746. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76331-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [117].Bean BP. Neurotransmitter inhibition of neuronal calcium currents by changes in channel voltage dependence. Nature. 1989;340:153–156. doi: 10.1038/340153a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [118].Elmslie KS, Zhou W, Jones SW. LHRH and GTP-gamma-S modify calcium current activation in bullfrog sympathetic neurons. Neuron. 1990;5:75–80. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90035-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [119].Boland LM, Bean BP. Modulation of N-type calcium channels in bullfrog sympathetic neurons by luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone: kinetics and voltage dependence. J Neurosci. 1993;13:516–533. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-02-00516.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [120].Roche JP, Treistman SN. The Ca2+ channel beta3 subunit differentially modulates G-protein sensitivity of alpha1A and alpha1B Ca2+ channels. J Neurosci. 1998;18:878–886. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-03-00878.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [121].Feng ZP, Arnot MI, Doering CJ, Zamponi GW. Calcium channel beta subunits differentially regulate the inhibition of N-type channels by individual Gbeta isoforms. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:45051–45058. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107784200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [122].Canti C, Bogdanov Y, Dolphin AC. Interaction between G proteins and accessory subunits in the regulation of 1B calcium channels in Xenopus oocytes. J Physiol. 2000;527(Pt 3):419–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00419.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [123].Meir A, Dolphin AC. Kinetics and Gbetagamma modulation of Ca(v)2.2 channels with different auxiliary beta subunits. Pflugers Arch. 2002;444:263–275. doi: 10.1007/s00424-002-0803-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [124].Currie KP. Inhibition of Ca2+ channels and adrenal catecholamine release by G protein coupled receptors. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2010;30:1201–1208. doi: 10.1007/s10571-010-9596-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [125].Wu L, Bauer CS, Zhen XG, Xie C, Yang J. Dual regulation of voltage-gated calcium channels by PtdIns(4,5)P2. Nature. 2002;419:947–952. doi: 10.1038/nature01118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [126].Gamper N, Shapiro MS. Regulation of ion transport proteins by membrane phosphoinositides. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:921–934. doi: 10.1038/nrn2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [127].Michailidis IE, Zhang Y, Yang J. The lipid connection-regulation of voltage-gated Ca(2+) channels by phosphoinositides. Pflugers Arch. 2007;455:147–155. doi: 10.1007/s00424-007-0272-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [128].Falkenburger BH, Jensen JB, Dickson EJ, Suh BC, Hille B. Phosphoinositides: lipid regulators of membrane proteins. J Physiol. 2010;588:3179–3185. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.192153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [129].Gamper N, Reznikov V, Yamada Y, Yang J, Shapiro MS. Phosphatidylinositol [correction] 4,5-bisphosphate signals underlie receptor-specific Gq/11-mediated modulation of N-type Ca2+ channels. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10980–10992. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3869-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [130].Suh BC, Leal K, Hille B. Modulation of high-voltage activated Ca(2+) channels by membrane phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. Neuron. 2010;67:224–238. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [131].Shimada T, Somlyo AP. Modulation of voltage-dependent Ca channel current by arachidonic acid and other long-chain fatty acids in rabbit intestinal smooth muscle. J Gen Physiol. 1992;100:27–44. doi: 10.1085/jgp.100.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [132].Barrett CF, Liu L, Rittenhouse AR. Arachidonic acid reversibly enhances N-type calcium current at an extracellular site. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;280:C1306–1318. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.280.5.C1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]