Abstract

Objective

Early infant diagnosis (EID) is the first step in HIV care, yet 75% of HIV-exposed infants born at two hospitals in Mozambique failed to access EID.

Design

Before/after study.

Setting

Two district hospitals in rural Mozambique.

Participants

HIV-infected mother/HIV-exposed infant pairs (N=791).

Intervention

We planned two phases of improvement using quality improvement methods. In Phase 1, we enhanced referral by offering direct accompaniment of new mothers to the EID suite, increasing privacy, and opening a medical record for infants prior to post-partum discharge. In Phase 2, we added enhanced referral activity as an item on the maternity register to standardize the process of referral.

Main outcome measure(s)

The proportion of HIV-infected mothers who accessed EID for their infant <90 days of life.

Results

We tracked mother/infant pairs from June 2009 to March 2011 (Phase 0: N=144; Phase 1: N=479; Phase 2: N=168), compared study measures for mother/infant pairs across intervention phases with chi-square, estimated time-to-EID by Kaplan-Meier, and determined the likelihood of EID by Cox regression after adjusting for likely barriers to follow-up. At baseline (phase 0), 25.7% of infants accessed EID <90 days. EID improved to 32.2% after Phase 1; only 17.3% received enhanced referral. After Phase 2, 61.9% received enhanced referral and 39.9% accessed EID, a significant three-phase improvement (p=0.007). In adjusted analysis, the likelihood of EID at any time was higher in the Phase 2 group vs. Phase 0 (aHR:1.68, 95%CI:1.19-2.37, p=0.003).

Conclusions

Retention improved by 55% with a simple referral enhancement. Quality improvement efforts could help improve care in Mozambique and other low-resource countries.

Keywords: HIV, Prevention of mother to child transmission / vertical transmission, Mozambique, Sub-Saharan Africa, quality improvement

INTRODUCTION

In 2009, an estimated 370,000 children acquired HIV infection through vertical transmission; while this number represents a 24% reduction in new infections since 2001, the persistence of new infections from mother-to-child transmission highlights the continued importance of HIV testing of at-risk infants.1 Successful prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) of HIV remains a challenge especially in many resource-limited settings where HIV is highly prevalent, making testing of exposed infants particularly important.1–5 Early infant diagnosis (EID) of HIV using dried-blood spot polymerase chain reaction testing has been shown to be feasible and effective for use in these settings, and allows for prompt identification and treatment of infected infants.6,7 Since early combination antiretroviral treatment (cART) significantly reduces infant mortality from HIV infection, successful EID programs are a crucial part of efforts to reduce the burden of HIV disease.8

Despite the importance of EID, program performance in many resource-limited settings has been disappointing, and factors such as patient attrition remain important barriers to higher uptake of testing.9–12 Infants who fail to access EID, in addition to missing the opportunity for prompt diagnosis of early HIV transmission, are deprived of the other HIV-related services bundled with testing, such as cotrimoxazole prophylaxis, breastfeeding counseling and testing for late transmission of infection. While socioeconomic factors are often cited as drivers of poor access to EID,4,5,10,13 there is increasing attention to the role that strengthening health systems may play in improving access and other program outcomes.9,14–16

In our previous work at one district hospital in Zambézia Province, Mozambique, we found that only 25% of all HIV-exposed infants born at the hospital returned for EID, though 49% of their mothers returned for their own HIV care.17 We hypothesized that this discrepancy was due in part to operational factors, and tested the idea that quality improvement methods could be used to design an intervention to improve infant retention in the EID programs at two district hospitals in Zambézia Province.

METHODS

Context

Zambézia Province is located in central Mozambique, is predominantly rural, and had an estimated adult HIV prevalence of 12.6% in 2009.18 HIV screening is routinely offered to women seeking prenatal care, and those who are HIV infected are offered antiretroviral prophylaxis or cART when eligible by national guidelines.19 EID services are offered in specialized clinics at all district hospitals in the province on an outpatient basis; these services include HIV testing of at-risk infants by dried blood spot polymerase chain reaction (DBS-PCR), provision of cotrimoxazole prophylaxis, and HIV-specific counseling and support (Table 1). We conducted this study at two district hospitals in Zambézia Province, in the districts of Alto Molócuè and Namacurra.

Table 1.

Mozambique’s 2009–2010 National Guidelines for Prevention of Mother-to-Child HIV Transmission (PMTCT) and Early Infant Diagnosis (EID)17,21

| Maternal PMTCT Guidelines | Infant PMTCT Guidelines | Infant EID Guidelines† |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) first-line regimen: zidovudine (300mg), lamivudine (150mg), and nevirapine (200mg) every 12 hours.

At-risk infants are followed monthly in the EID clinic, starting at 4 weeks of life. Infants diagnosed with HIV infection are referred for cART initiation.

Determine® and UniGold™ rapid immunoassay tests for HIV, used sequentially.

Design, Population and Measures

We used the conceptual framework for quality improvement developed by Langley and colleagues20 to assess the process of care delivered to HIV-infected mothers who gave birth to a live infant at the two study hospitals, design and implement two phases of intervention, and evaluate the interventions using a before/after study design. All HIV-infected mother/HIV-exposed infant pairs born at the district hospitals of Alto Molócuè and Namacurra between June 2009 and December 2010 were eligible for analysis; this 19 month interval was defined as the enrollment period. The primary study outcome was the proportion of hospital-born, HIV-exposed infants who successfully accessed EID within 90 days of birth. Secondary outcomes were: (1) the proportion of infants who accessed EID regardless of time; (2) the time to the initial EID visit; (3) the proportion of post-partum, HIV-infected women who received the study intervention; and (4) the proportion of HIV-exposed infants who were tested for HIV by DBS-PCR. Demographic information routinely collected as part of clinical care was abstracted as part of the study evaluation. Clinical data from all mother/infant pairs was tracked for at least 3 months from birth; final data collection took place in April 2011.

Process of EID Referral at Baseline (Phase 0)

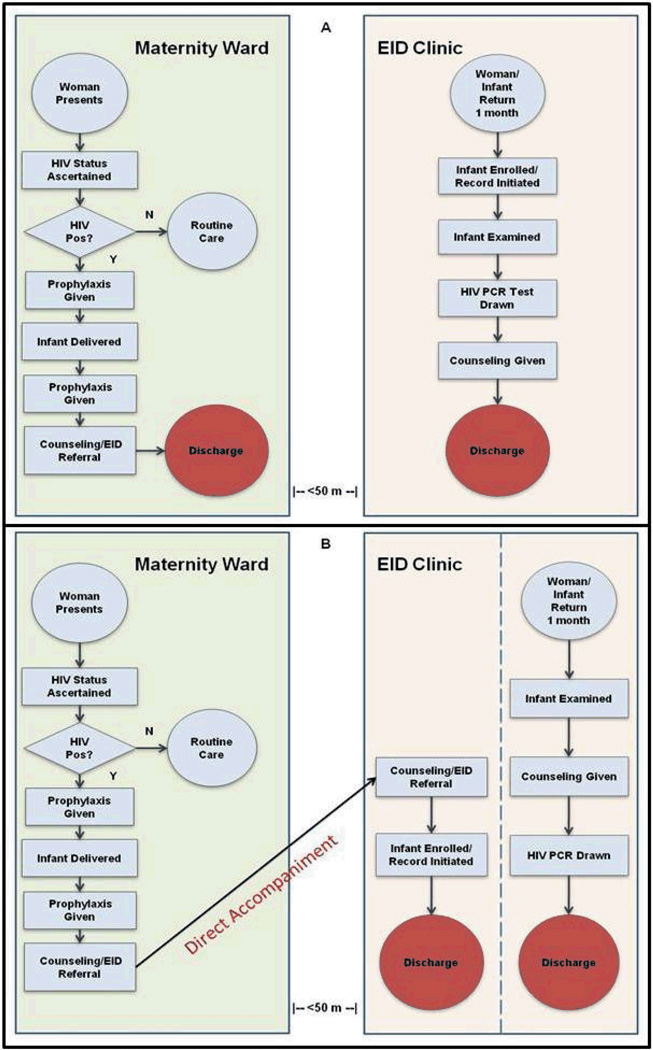

All women who presented for labor at both study hospitals had their HIV-status ascertained on intake; women with unknown HIV status or who tested negative more than three months before delivery were given a rapid HIV test on an opt-out basis. Clinical data for each HIV-infected mother were recorded in a maternity register; this included information such as basic demographics, cART regimen and administration, and date/time of delivery. Post-delivery, HIV-infected women were given post-partum counseling prior to discharge regarding the need to return with their infants for EID in one month. Counseling was conducted by the maternal/child health nurses and took place in an open maternity ward, often proximate to other patients. After counseling was completed, mothers and infants were discharged from the hospital. For infants that returned with their mothers to access EID, the infant was enrolled in the EID clinic and basic demographic information about the mother and the infant were recorded in a clinic register. An infant medical record was also generated by the EID nurse during enrollment. Mothers were counseled to return to the EID clinic with their infant for subsequent visits. At both study sites, prenatal, maternity, and EID services took place in three separate structures within a roughly 50-meter radius on the hospital grounds.

Phase 1 Intervention

Staff were introduced to the Langley, et al. model for quality improvement (QI)20 and were given the opportunity to participate in the process of designing an intervention aimed at impacting infant retention in EID. This model of QI conceptualizes the process of improvement around the Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) Cycle. The model guides the process of: (1) setting specific aims for improvement, mapping the process of care to identify key barriers, and developing an intervention to address those barriers (Plan); (2) implementing a pilot intervention (Do); (3) evaluating the effectiveness of the pilot intervention (Study); and (4) scaling, modifying or discarding the intervention based on that evaluation (Act). The model is iterative, and the goal is for each PDSA cycle to incorporate the experience of the previous phase of improvement to achieve better outcomes over time.

We conducted unstructured interviews with maternal/child nursing staff at both hospitals, and revealed several potential barriers facing HIV-infected women that could possibly prevent EID access for their newborn. We focused discussion on barriers that could be possibly overcome with a clinic-based intervention. Staff identified the standard process of referral to the EID clinic during maternity discharge as a potential target for improvement for three reasons: (1) after standard referral counseling, many women lacked adequate knowledge of the need for EID or the location of EID services; (2) the lack of privacy for women during referral counseling possibly increased stigma and decreased the effectiveness of counseling; and (3) the ability to track HIV-exposed infants who dropped out of care was limited by the practice of deferring initiation of the medical record until the time of the initial EID visit.

To address these barriers, several nurses working in Namacurra district hospital described their attempt to enhance the process of referral to EID for their post-partum patients by offering to accompany them to the site of EID at the time of maternity discharge. Within the EID suite, these nurses offered counseling in a private setting and initiated a medical record for infants prior to discharge (Figure 1). After this idea was introduced to all nursing staff at both study hospitals, staff agreed to implement enhanced referral as standard practice at both sites in September 2009 as a Phase 1 intervention. This intervention had three components: (1) all HIV-infected, post-partum women who gave birth in the maternity ward would be offered the opportunity to be accompanied by one of the maternity nurses to the site of EID services prior to discharge; (2) in the privacy of the EID clinic suite, a mother would be offered HIV counseling by the accompanying nurse that focused on care of her at-risk infant and the need for EID; and (3) information about the newborn infant would be recorded in the clinic register and a medical record would be generated.

Fig. 1.

Flowcharts depicting the process of maternity and early infant diagnosis (EID) services delivered to HIV-infected mothers/HIV-exposed infants during standard referral (Panel A) and enhanced referral (Panel B).

Phase 2 Intervention

In August 2010, we reviewed data from the first phase of improvement and performed an interim analysis to evaluate the effectiveness of enhanced referral on retention; early results were promising and published previously.21 To further improve outcomes, a second phase of improvement was introduced aimed at improving the proportion of eligible women who received enhanced referral at both sites. Staff feedback indicated that factors such as staff turnover and difficulty remembering to offer enhanced referral to patients in the context of their other duties were major barriers to offering enhanced referral to more patients.

With these barriers in mind, we sought to standardize the process of referral by adding a column in the maternity register for nurses to sign if they had offered their post-partum patient enhanced referral and accompanied her to the EID suite. Staff felt that this intervention would improve recall, allow for accountability, and allow them to document this activity in the same way they did for their other clinical duties. This intervention was formally implemented at both sites in August 2010.

Data Analysis

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the National Committee of Bioethics for Health in Mozambique and the Institutional Review Board of Vanderbilt University. Both committees approved a waiver of informed consent for participants.

We reviewed mothers’ charts and abstracted relevant data of all HIV-infected mothers that delivered a live infant from June 1, 2009 through September 11, 2009 (Phase 0), September 12, 2009 through August 20, 2010 (Phase 1) and August 21 through December 31, 2010 (Phase 2). Maternal/child follow-up for EID and infant HIV testing by DBS-PCR were determined by review of the maternity and EID service register. Maternal names, home village and infant date-of-birth were abstracted from the maternity register for all HIV-infected/HIV-exposed infant pairs; maternal name, home village and infant date-of-birth were abstracted from EID clinic registers. Mother/infant pairs with matched, identifiable information on both registries were considered to have accessed EID. All mother/infant pairs were tracked from the time of birth until either an initial EID visit or the end of the study period (March 2011).

Selected sociodemographic characteristics of the study population were reported as medians or proportions; these were tabulated to describe woman/infant pairs in each interventional phase and separately by receipt of standard vs. enhanced referral. Pearson’s chi squared test was used to compare the characteristics of woman/infant pairs in each intervention phase, and separately for pairs who received standard vs. enhanced referral. We compared the aggregate rate of infant EID access before (Phase 0) and after implementation of enhanced referral (Phase 1) and the register of maternity activities (Phase 2) using an intention-to-treat analysis. The proportion of mothers who received enhanced referral, infants who accessed EID within 90 days of life, infants who accessed EID regardless of time, and the infants who were tested for HIV by DBS-PCR were compared across intervention phases, assessing statistical significance by the chi-squared test for trend. Kaplan-Meier estimates were used to compute time-to-EID access by intervention phase; estimates were compared by log-rank test. A second set of Kaplan-Meier estimates were used to compute time-to-EID by receipt of enhanced vs. standard referral to estimate the effectiveness of each intervention by per-protocol analysis. Cox proportional hazard models compared time-to-EID by intervention phase (intention-to-treat) and by referral type (per-protocol). These models were adjusted for known demographic predictors to follow-up (selected a priori), including maternal age, source of income, number of children, cART status, distance from home to the hospital (≥or <10 km) and hospital site. Missing demographic information was accounted for using multiple imputation methods.

RESULTS

A total of 791 records representing discrete mother/infant pairs from hospital births between June 2009 and December 2010 were included in analyses (Phase 0: N=144, Phase 1: N=479, Phase 2: N=168). During the 19-month study enrollment period, 507 women delivered at the district hospital in Namacurra and 284 delivered in Alto Molócuè. Mothers were predominately young (median age, 22 years), worked in agriculture (78.0%), and lived within 10 km of the district hospital (82.4%). In the total sample, 19.2% of women were receiving cART during pregnancy (Table 2). While there were no statistically significant differences in demographic characteristics between women in the Phase 0 and Phase 1 populations, women in the Phase 2 population were more likely to have jobs in agriculture, to live ≥10 km from the hospital and to be receiving cART for their HIV infection. A greater proportion of women who received enhanced referral were receiving cART compared to those who received standard referral (28.0% vs. 15.3%, p<0.001). Women who received enhanced referral also had a higher median number of children (2 vs. 1, p<0.001). There were no statistically significant differences for women in the enhanced vs. standard referral group for median age, occupation type, or distance to the hospital (Table 3).

Table 2.

Characteristics of post-partum, HIV-infected mothers during each phase of improvement

| Characteristic | Total | Phase 0 | Phase 1 | Phase 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=791 | N=144 | N=479 | N=168 | |

| Median Maternal Age (Years, IQR) | 22 (19–27) | 23 (20–28) | 22 (19–26) | 23 (20–27) |

| Median Number of Children (IQR) | 1 (1–3) | 1 (1–3) | 1 (1–2) | 2 (1–3) |

| Maternal Occupation, % | ||||

| Agriculture | 78.0 | 77.1 | 74.8 | 87.5 |

| Job outside home | 11.0 | 9.2 | 12.2 | 9.4 |

| Student | 11.0 | 13.8 | 13.0 | 3.1 |

| Distance from Hospital, % | ||||

| < 10 km | 82.4 | 87.2 | 85.3 | 70.5 |

| ≥ 10 km | 17.6 | 12.8 | 14.7 | 29.5 |

| Mother on cART, % | 19.2 | 18.2 | 15.7 | 30.8 |

Phase 0 (baseline): June 1—September 11, 2009

Phase 1 improvement: September 12, 2009—August 20, 2010

Phase 2 improvement: August 21—December 31, 2010

cART = combination antiretroviral therapy

Table 3.

Characteristics of 791 women/infant pairs who received standard and enhanced referral to Early Infant Diagnosis Services

| Characteristic | Referral Type |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard N=591 |

Enhanced N=200 |

||

| Median Maternal Age (Years) | 22 | 22 | 0.4 |

| Median Number of Children | 1 | 2 | <0.001 |

| Maternal Occupation, % | 0.7 | ||

| Agriculture | 78.3 | 77.2 | |

| Job outside home | 10.3 | 12.5 | |

| Student | 11.3 | 10.3 | |

| Distance from Hospital, % | |||

| ≥ 10 km | 16.3 | 20.4 | 0.2 |

| Mother on cART, % | 15.3 | 28.0 | <0.001 |

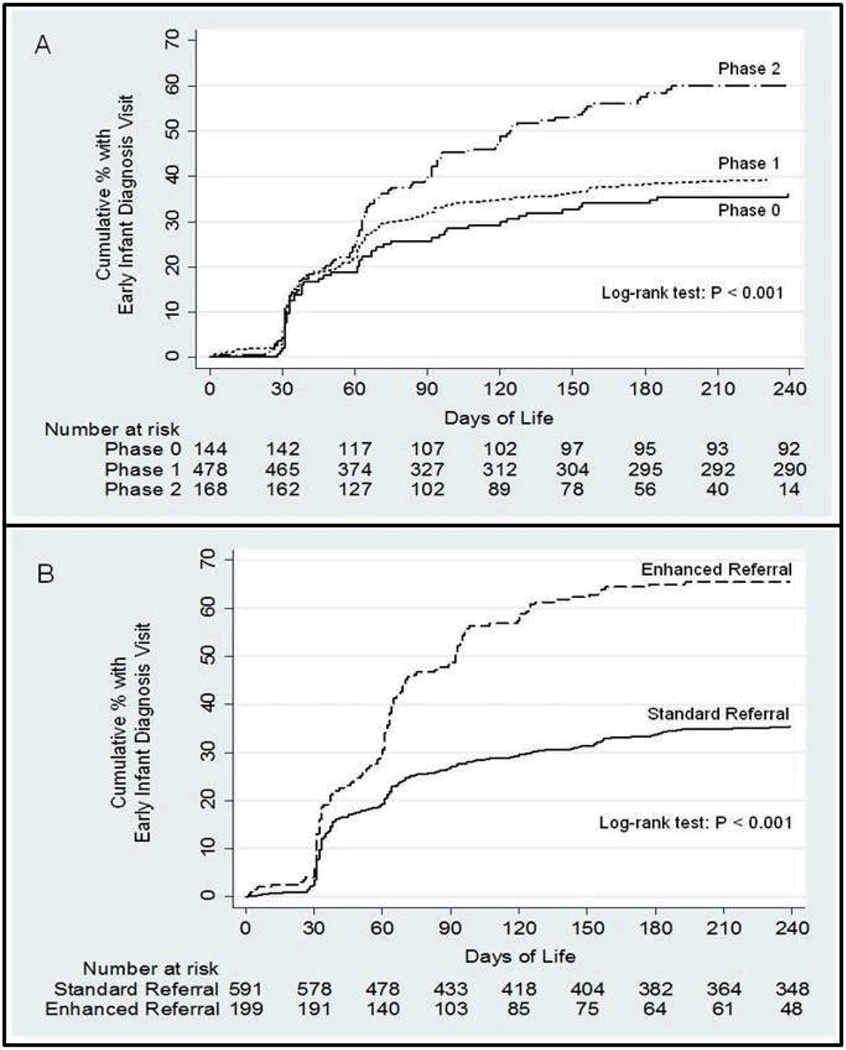

At baseline (Phase 0), 9.0% of post-partum women received enhanced referral and 25.7% returned to access EID for their infant within 90 days. The women who received enhanced referral during Phase 0 reflect the work of the nurses in Namacurra who developed the intervention prior to the commencement of the present study. After implementation of the Phase 1 intervention, 17.3% of women received enhanced referral, and 32.2% accessed EID for their infant within 90 days. After implementation of the Phase 2 intervention, 61.9% of women received enhanced referral, and 39.9% accessed EID within 90 days. Improvement was statistically significant for both receipt of enhanced referral (p-trend<0.001) and EID (p-trend=0.007) across the interventional phases. Likewise, the proportion of mother/infant pairs who accessed EID at any time point improved significantly after the two intervention phases (38.2% vs. 40.5% vs. 58.9%, p-trend<0.001), as did the proportion of infants who were tested for HIV with DBS-PCR during the initial EID visit (28.5% vs. 34.0% vs. 51.2%, p <0.001) (Table 4). For women who received standard referral, there was no evidence of change across intervention phases in the proportion who accessed EID for their infants within 90 days (26.7% vs. 28.0% vs. 21.9%, p-trend=0.6) or at any follow-up time (39.7% vs. 36.4% vs. 31.3%, p-trend=0.5).

Table 4.

Study outcomes for 791 HIV-infected mother/HIV-exposed infant pairs

| Study Outcome | Phase 0 N = 144 |

Phase 1 N= 479 |

Phase 2 N= 168 |

P-trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Received enhanced referral, % | 9.0 | 17.3 | 61.9 | < 0.001 |

| Initial EID visit (≤90 days), % | 25.7 | 32.2 | 39.9 | 0.007 |

| Initial EID visit (any time), % | 38.2 | 40.5 | 58.9 | <0.001 |

| HIV PCR tested, % infants | 28.5 | 34.0 | 51.2 | <0.001 |

EID = Early Infant Diagnosis; PCR = Polymerase Chain Reaction

Figure 2 depicts the time to EID access for mother/infant pairs by intervention phase and by receipt of standard vs. enhanced referral. In multivariable analyses adjusting for maternal age, number of children at home, distance from home to the health center, source of income, maternal cART status and hospital site, there was a small, non-significant increase in the likelihood of accessing EID for mother/infant pairs during the Phase 1 vs. Phase 0 intervention (aHR 1.17, 95%CI 0.86-1.58, p=0.3). In contrast, there was a statistically significant increase in the likelihood of accessing EID for those mother/infant pairs in the Phase 2 group relative to those at baseline (aHR 1.68, 95%CI 1.19-2.37, p=0.003). Mother/infant pairs who received enhanced referral had a significantly increased rate of EID access at any time compared to those who received standard referral (66.0% vs. 36.6%, p<0.001). There was a significant increase in the likelihood of accessing EID for women who received enhanced vs. standard referral in multivariable analysis (aHR 1.93, 95%CI 1.53-2.44, p<0.001).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of time from birth to access of early infant diagnosis (EID) for HIV-exposed infants before and after two intervention phases (Panel A), and by receipt of enhanced vs. standard referral (Panel B).

DISCUSSION

With two successive interventions that focused on improving health systems barriers, the proportion of mother/infant pairs that succeeded in accessing EID within three months of life improved by 55% at two rural hospitals in Mozambique. Even after accounting for other known predictors of EID access, women who received enhanced referral were nearly twice as likely to obtain EID for their infants compared to those who received standard care. Enhanced referral improved on standard care by more tightly linking maternity and EID services through direct accompaniment and by providing privacy for women during counseling; these enhancements potentially led to more women seeking EID for their infants. Incorporating enhanced referral into the routine documentation of maternity staff improved implementation by providing a prompt for providers and a method for clinic leaders to give feedback to individual providers. The study interventions were simple, required no additional staff to execute, and were well accepted by the staff and patients. The increased number of at-risk infants who accessed EID services did not result in less consistent delivery of infant HIV PCR testing, suggesting that improving one care delivery component did not overwhelm another. These practical, logistical factors are particularly important for severely resource-constrained settings such as rural Mozambique.22

This study demonstrates the benefit that can be realized by using a quality improvement approach that fosters a partnership with front-line staff to improve performance at the local level. Enhanced referral was developed by a handful of nurses in response to their direct experience of patient need, and thus was based on contextual information that is often unavailable to those working at the programmatic level. Input from the program level provided data that acted as an objective measure of performance — something that was normally unavailable to staff — and served as an important motivating agent for change. The quality improvement approach enabled an idea that succeeded on an individual level to be spread to a larger context, on a scale that could impact an important programmatic outcome. Since the study team interacted with staff on two brief occasions during Phase 1 and 2 planning, these interventions were sustained only by the daily action of local staff who felt a sense of ownership of the ideas they helped create.

The strengths of this study were the simplicity of the interventions, the magnitude of impact on a program indicator with significant clinical relevance, and an evaluation that accounted for known confounders. Findings from the study are limited by the uncontrolled study design and the possibility that unmeasured confounding, especially selection bias, may have had an impact on our results. While some differences between women who received standard vs. enhanced referral, such as the higher proportion of women on cART in the enhanced referral group, were accounted for in multivariable modeling, factors such as the time of discharge, content of counseling and relation of enhanced referral delivery to individual providers were not measured and may be confounding. While we cannot exclude the possibility of a secular trend accounting for the improvement over time noted in our results, the association of receipt of enhanced referral and follow-up and the lack of improvement in follow-up over time for women receiving standard care argues strongly against this as a significant factor. The study was not designed to measure mother/infant pairs who did not receive EID due to infant mortality, or who may have accessed EID at other health facilities due to migration; since EID services are centralized and the distance between hospitals that provide these services is substantial, misclassification from migration is likely minimal. The name-matching technique used to classify mother/infant pairs as receiving enhanced referral and EID was another source of potential misclassification, but this is a conservative bias that, if present, would underestimate the impact of our program. The study was not designed to capture delivery of other EID clinic services, such as cotrimoxazole prophylaxis or breast-feeding counseling, that are also important interventions delivered to HIV-infected mother/HIV-exposed infant pairs.

While there was a significant improvement in both implementation of enhanced referral and initial follow-up for EID, approximately 40% of eligible mothers after the second phase of intervention did not receive the study intervention; a similar proportion failed to return for EID. While this study was not designed to explore factors that limited delivery of enhanced referral after the second interventional phase, barriers such as limited nurse staffing and high staff turnover are likely to be important. Mothers may have opted out of enhanced referral due to HIV-related stigma or fear of disclosure. The rate of increase in the proportion of women/infant pairs receiving enhanced referral was higher than the rate of increase in EID access within 90 days, while the rate of access to EID at any time point was more in-line with the increase in enhanced referral. It may be that enhanced referral was more effective in encouraging follow-up than it was in encouraging prompt follow-up; access to early EID may be more sensitive to sociodemographic factors such as access to transportation.

The study was not designed to discern if there are specific factors that make enhanced referral more or less effective on an individual basis; for instance, women who possess a high level of knowledge about HIV may not benefit additionally from enhanced referral. Since 44% of women who received enhanced referral did not access EID with their infants, there are barriers to access that our interventions did not address. Our study interventions would have been strengthened by incorporating patients’ perspectives on barriers to EID and the acceptability of enhanced referral into our improvement strategy; both are strategies we plan to incorporate in future work. Additionally, since infants whose mothers received enhanced referral had medical records initiated prior to discharge, those rosters could be used in future interventions to promote active community searching for HIV-exposed infants who had not accessed EID.

Quality improvement methods have been cited as crucial tools to strengthen health systems and make the best use of available resources in developing countries.15,16 Despite the clear potential for improving processes such as PMTCT and EID where successful outcomes depend on a cascade of events, this study is one of few that describe the application of quality improvement methods toward that end.14,23,24 The interventions piloted during this study are straightforward to scale-up, and we are currently in the process of using a step-wedge study design to evaluate enhanced referral at 10 district hospitals in Zambézia Province. If our expanded intervention proves successful, we believe this model for innovation and spread would have wide application to other problems and settings within low and middle income countries.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the nursing staff of Alto Molócuè and Namacurra district hospitals, the women who participated in our study, Sérgio Patrício and Madalena Vundo for their assistance with implementation and data collection.

The HIV/AIDS Treatment and Care program in Zambézia is supported by PEPFAR through the CDC Global AIDS Program (grant U2GPS000631). Dr. Ciampa was supported by the Veteran’s Affairs Quality Scholars Fellowship Program. Dr. Tique was supported, in part, by NIH grant # D43TW001035 (AIDS International Training and Research Program). Funders had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish or preparation of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.UNAIDS. Global Report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic 2010. 2010 Available at: http://www.unaids.org/globalreport/Global_report.htm.

- 2.Stringer EM, Ekouevi DK, Coetzee D, et al. Coverage of nevirapine-based services to prevent mother-to-child HIV transmission in 4 African countries. JAMA. 2010;304:293–302. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stringer EM, Sinkala M, Stringer JS, et al. Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in Africa: successes and challenges in scaling-up a nevirapine-based program in Lusaka, Zambia. AIDS. 2003;17:1377–1382. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000060395.18106.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perez F, Mukotekwa T, Miller A, et al. Implementing a rural programme of prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in Zimbabwe: first 18 months of experience. Trop Med Int Health. 2004;9:774–783. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2004.01264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manzi M, Zachariah R, Teck R, et al. High acceptability of voluntary counselling and HIV-testing but unacceptable loss to follow up in a prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission programme in rural Malawi: scaling-up requires a different way of acting. Trop Med Int Health. 2005;10:1242–1250. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sherman GG, Stevens G, Jones SA, et al. Dried blood spots improve access to HIV diagnosis and care for infants in low-resource settings. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;38:615–617. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000143604.71857.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sherman GG, Cooper PA, Coovadia AH, et al. Polymerase chain reaction for diagnosis of human immunodeficiency virus infection in infancy in low resource settings. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24:993–997. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000187036.73539.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Violari A, Cotton MF, Gibb DM, et al. Early antiretroviral therapy and mortality among HIV-infected infants. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2233–2244. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0800971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braun M, Kabue MM, McCollum ED, et al. Inadequate Coordination of Maternal and Infant HIV Services Detrimentally Affects Early Infant Diagnosis Outcomes in Lilongwe, Malawi. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011 Jan 10; doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31820a7f2f. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nyandiko WM, Otieno-Nyunya B, Musick B, et al. Outcomes of HIV-exposed children in western Kenya: efficacy of prevention of mother to child transmission in a resource-constrained setting. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;54:42–50. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181d8ad51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahoua L, Ayikoru H, Gnauck K, et al. Evaluation of a 5-year programme to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV infection in Northern Uganda. J Trop Pediatr. 2010;56:43–52. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmp054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Lettow M, Bedell R, Landes M, et al. Uptake and outcomes of a prevention-of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) program in Zomba district, Malawi. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:426. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones SA, Sherman GG, Varga CA. Exploring socio-economic conditions and poor follow-up rates of HIV-exposed infants in Johannesburg, South Africa. AIDS Care. 2005;17:466–470. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331319723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Youngleson MS, Nkurunziza P, Jennings K, Arendse J, Mate KS, Barker P. Improving a mother to child HIV transmission programme through health system redesign: quality improvement, protocol adjustment and resource addition. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13891. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leatherman S, Ferris TG, Berwick D, et al. The role of quality improvement in strengthening health systems in developing countries. Int J Qual Health Care. 2010;22:237–243. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzq028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization. Strengthening Health Systems to Improve Health Outcomes. 2007 Available at: http://www.wpro.who.int/sites/hsd/documents/Everybodys+Business.htm.

- 17.Cook RE, Ciampa PJ, Sidat M, et al. Predictors of successful early infant diagnosis of HIV in a rural district hospital in Zambezia, Mozambique. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;56:e104–e109. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318207a535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ministério da Saúde. Relatório preliminar sobre a prevalência da infecção por HIV. Maputo, Mozambique. 2010 Available at: http://www.misau.gov.mz/pt/hiv_sida/insida.

- 19.Comité Nacional de Tratamento Antiretroviral. Guia de Tratamento Antiretroviral e Infecções Oportunistas no Adulto, Adolescente e Grávida 2009/2010. 2009 Available at: http://www.misau.gov.mz/pt/hiv_sida/.

- 20.Langley G, Nolan K, Nolan T, Norman C, Provost L. The improvement guide: a practical approach to enhancing organizational performance. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ciampa PJ, Burlison JR, Blevins M, et al. Improving retention in the early infant diagnosis of HIV program in rural Mozambique by better service integration. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;58:115–119. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31822149bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Audet CM, Burlison J, Moon TD, et al. Sociocultural and epidemiological aspects of HIV/AIDS in Mozambique. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2010;10:15. doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-10-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sripipatana T, Spensley A, Miller A, et al. Site-specific interventions to improve prevention of mother-to-child transmission of human immunodeficiency virus programs in less developed settings. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197((3 Suppl)):S107–S112. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.03.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Doherty T, Chopra M, Nsibande D, et al. Improving the coverage of the PMTCT programme through a participatory quality improvement intervention in South Africa. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:406. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]