Abstract

Objective

To compare a 2 day bowel preparation regime of barium, iodine and a mild stimulant laxative with a 1 day iodine-only regime for CT colonography (CTC).

Methods

100 consecutive patients underwent CTC. The first 50 patients (Regime 1) ingested 1 bisacodyl tablet twice a day 3 days before CTC and 1 dose each of 50 ml of barium and 20 ml of iodinated contrast per day starting 2 days before CTC. The second 50 patients (Regime 2) ingested 3 doses of iodinated contrast over 24 h prior to CTC. Volumes of residual stool and fluid, and the effectiveness of stool and fluid tagging, were graded according to methods established by Taylor et al (Taylor S, Slaker A, Burling D, Tam E, Greenhalgh R, Gartner L, et al. CT colonography: optimisation, diagnostic performance and patient acceptability of reduced-laxative regimens using barium-based faecal tagging. Eur Radiol 2008; 18: 32–42). A 3 day low-residue diet was taken by both cohorts. Questionnaires rating the side-effects and burden of the bowel preparation were compared to a control cohort of patients undergoing barium enema.

Results

The proportion of colons producing none/scattered stool (score 1) was 90.3% with Regime 1 and 65.0% with Regime 2 (p<0.005). Any residual stool was significantly better tagged with Regime 1 (score 5), with 91.7% of Regime 1 exhibiting optimum tagging vs 71.3% of Regime 2 (p<0.05). No significant differences in side-effects between the bowel preparation regimes for CTC were elicited. Bowel preparation for barium enema was tolerated significantly worse than both of the CTC bowel preparation regimes.

Conclusion

Regime 1, containing a 3 day preparation of a mild laxative, barium and iodine, produced a significantly better prepared colon, with no difference in patient acceptability.

CT colonography (CTC) requires a well-prepared bowel to enable accurate detection and characterisation of colorectal polyps and carcinomas. Bowel preparation regimes vary among different institutions. These encompass solely cathartic bowel preparation with agents used traditionally to prepare bowel for colonoscopy such as polyethylene glycol or sodium phosphate [1,2]. Full cathartic bowel preparation is associated with significant side-effects, including diarrhoea, abdominal pain and disruption to activities of daily living [3,4], and in extreme cases even death [5]. Previous studies have shown that patients often regard such bowel preparation for bowel investigation as the most burdensome part of the process [6,7]. This has a significant impact in the context of screening for bowel cancer as patient compliance is central for a successful programme [8]. More recently there has been a vogue towards using oral contrast medium to “tag” residual faeces and fluid with the use of fewer laxatives [9,10], or even with oral contrast medium alone [11-15]. This approach means a less vigorous bowel preparation can be used, as any residual matter can be accurately delineated from mucosal abnormalities on the basis of its higher attenuation. When adopting this approach to bowel preparation, it is imperative to ensure that residual material is thoroughly and homogeneously tagged, and that this can be readily differentiated from normal and abnormal mucosa. Employing this technique enables a reduction in the amount of bowel catharsis necessary to be able to accurately identify mucosal anomalies, and thus increase patient acceptability and willingness to undergo the examination [16,17].

Tagging materials can consist of iodine- and/or barium-based agents. Some authors believe that barium predominately tags the more solid elements of the retained colonic residue [18]. Hyperosmolar iodine-based contrast agents promote stool softening by inducing colonic fluid secretion. This allows homogeneous tagging of both solid and fluid residue, but can induce significant diarrhoea when administered in large volumes.

To date there remains no consensus on the optimum way to tag bowel residue—neither which contrast agent nor the volumes or timing for administration, nor whether additional laxatives are necessary.

The aim of this study was to compare primarily the image quality achieved and the patient acceptance of two different regimes encompassing different elements of bowel preparation. The first used both iodine and barium as tagging agents with a mild laxative over 2 days (Regime 1) and the second was a minimal preparation regime, using iodine alone over 24 h (Regime 2).

Methods and materials

This study consists of two main parts. The first aim of this study was to evaluate the technical performance of two different bowel preparation regimes in terms of the volume of residual stool and fluid, and the quality of the tagging of retained material. Indications for referral for CTC were (1) increased risk of colorectal cancer from family or personal history in asymptomatic patients and (2) recent onset of concerning symptoms (e.g. rectal bleeding, iron deficiency anaemia and change in bowel habit).

The first 50 patients undergoing CTC after January 2009 at each of 2 different hospitals employing different faecal tagging regimes were selected and retrospectively analysed. The two hospitals belong to the same NHS trust and serve the same population. In total, 100 patients were included in this technical performance arm of the study. Each patient had all 6 colonic segments included and analysed, totalling 600 colonic segments. Patients with prior personal history of colorectal carcinoma or previous colonic resection, as well as patients with a contraindication to iodine administration, were excluded from the analysis.

The second part of the study was a prospective evaluation by means of a questionnaire regarding the effects of the bowel preparation of three groups of patients. The first cohort underwent investigation using Regime 1 and included 57 patients. The second cohort ingested Regime 2 for CTC and included 54 patients. A third cohort of 59 patients undergoing barium enema examination was used as a control group for analysis of patient tolerance to traditional cathartic bowel preparation, which some centres continue to employ. The questionnaires were collected continuously until 50 complete questionnaires had been acquired from each cohort. There were seven incomplete questionnaires from Regime 1, four from Regime 2 and nine from the barium enema group. These were therefore excluded and only the 50 completed questionnaires were used in the subsequent analysis.

The patients used for both study components undertook identical bowel preparation regimes and were referred from the same catchment population of the two hospitals under the same referral criteria.

Ethics approval was waived for the first part as it was a retrospective analysis of the technical performance of the bowel preparation. Ethics approval was granted for the questionnaire forming the second part of the study by the trust's clinical audit advisory committee.

Bowel preparation

Patients undergoing CTC in both preparation groups were asked to adhere to the same low-residue diet for 72 h days prior to CTC.

The first consecutive 50 patients (Regime 1) were asked to take a mild laxative, bisacodyl, 5 mg twice a day for the 3 days prior to CTC. In addition, they were asked to take one 50 ml dose of Microcat® (5% w/v barium sulphate; Guerbet, Solihull, UK) mixed with 200 ml of water and one 20 ml dose of Gastrografin® (100 mg sodium diatrizoate and 660 mg meglumine diatrizoate per ml; Bayer, Newbury, UK) together in the morning for 2 days prior to CTC and a further dose of each on the morning of the examination. The Regime 1 group therefore ingested a total of 150 ml 5% w/v barium and 60 ml of Gastrografin for faecal tagging.

The second consecutive 50 patients (Regime 2) were asked to take 3 aliquots of Gastrografin in the 24 h preceding examination: 35 ml of Gastrografin at lunch and dinner the day before CTC and a further 30 ml on the morning of the examination. The Regime 2 group therefore ingested a total of 100 ml of Gastrografin for faecal tagging.

A summary of the bowel preparation regimes for CTC is given in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of bowel preparation regimes.

| Regime | 3 days before CTC | 2 days before CTC | 1 day before CTC | Morning of CTC |

| Regime 1 | 1×bisacodyl tablet bd | 1×bisacodyl tablet bd | 1×bisacodyl tablet bd | 50 ml Microcat |

| 50 ml Microcat | 50 ml Microcat | 20 ml Gastrografin | ||

| 20 ml Gastrografin | 20 ml Gastrografin | |||

| Regime 2 | 35 ml Gastrografin at lunch and dinner | 30 ml Gastrografin | ||

| Barium enema preparation | 2×Picolax sachets |

bd, twice daily; CTC, CT colonography.

The control group of patients undergoing barium enema ingested two sachets of Picolax (Ferring Pharmaceuticals Ltd, West, Drayton, UK; sodium picosulphate 10.0 mg, magnesium oxide 3.5 g, citric acid 12.0 g) in the 24 h before examination.

CT colonography technique

CT was performed on a four-slice Marconi Mx8000 CT system (Philips Healthcare, Best, Netherlands) for the Regime 1 group at a slice thickness of 1 mm, pitch 1.5, tube voltage 120 kV and tube current varied according to the patient's body habitus. The Regime 2 group were examined on a 64-slice Siemens CT system (Siemens Medical Solutions, Forchheim, Germany) at a slice thickness of 0.6 mm, pitch 1.5, tube voltage 120 kV and tube current of 100 mAs. 3 mm axial slice reconstructions were sent by both scanners to local picture archiving and communications system (PACS) servers for assessment. Patients were given 20 mg of intravenous butylscopolamine bromide (Buscopan®; Boehringer Ingelheim, Bracknell, UK) or 1 mg of glucagon hydrochloride if Buscopan was contraindicated to ensure bowel paralysis. For patients who ingested Regime 1, colonic distension was achieved by manual air insufflation by the supervising radiologist until adequate distension had been achieved or patient tolerance allowed. Patients taking Regime 2 underwent automated CO2 insufflation. Patients were imaged in supine and prone positions (or lateral decubitus if patient could not tolerate prone scanning).

Image quality evaluation

Images were reviewed on a GE PACS RA 1000 workstation (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) using a primary two-dimensional technique by two experienced radiologists. Each radiologist was blinded to the type of bowel preparation regime. No restriction was placed on windowing and the radiologist was encouraged to utilise the full range of processing tools as required. The amount of residual faeces was graded according to criteria established by Taylor et al [19], as illustrated in Table 2. These criteria were applied to the quality of the faecal tagging, as well as the volume of residual fluid and the quality of the tagging thereof. The evaluations were repeated for each of the colonic segments: caecum, ascending, transverse, descending, sigmoid and rectum. The part of the segment that yielded the worst score (e.g. the highest residual volume and lowest tagging quality scores) was used to allocate the score for that segment. Examples of colons achieving the optimum preparation criteria and those that were poorly prepared are shown in Figures 1 and 2, respectively.

Table 2. Criteria used to grade residual stool and fluid volumes and tagging quality.

| Parameter | Grade | Criteria |

| Total volume of solid faecal residue | 1 | None or scattered stool only |

| 2 | Coating of <25% of lumen diameter or circumferential film of <2 mm | |

| 3 | Coating of 25–50% of lumen diameter | |

| 4 | Coating of >50% of lumen diameter | |

| Quality of faecal tagging | 1 | All residual stool untagged |

| 2 | 0–25% tagged | |

| 3 | 25–50% tagged | |

| 4 | 50–75% tagged | |

| 5 | 75–100% tagged | |

| Volume of residual fluid | 1 | No fluid |

| 2 | 0–25% anteroposterior diameter | |

| 3 | 25–50% anteroposterior diameter | |

| 4 | >50% anteroposterior diameter | |

| Quality of fluid tagging | 1 | Untagged |

| 2 | Layered tagging of differing densities | |

| 3 | Homogeneous tagging of single uniform density |

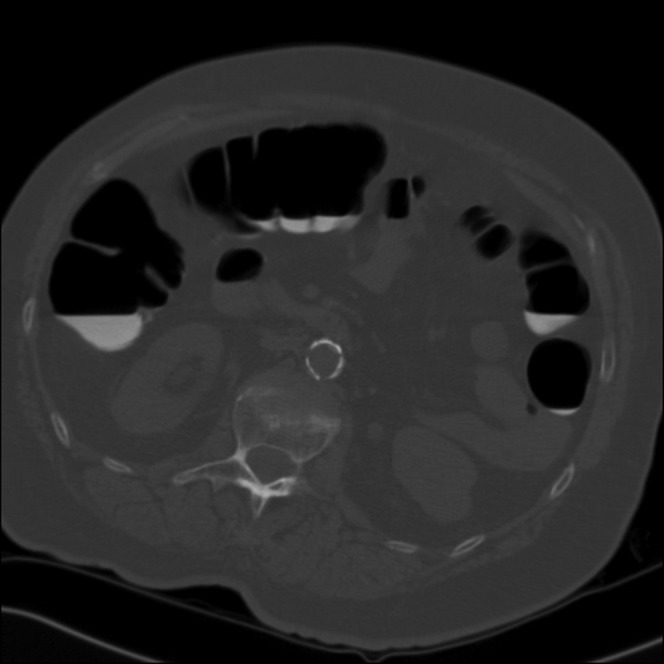

Figure 1.

A 72-year-old male with change in bowel habit. Axial CT colonographic image demonstrating no residual stool (grade 1) with homogeneously tagged fluid (grade 3).

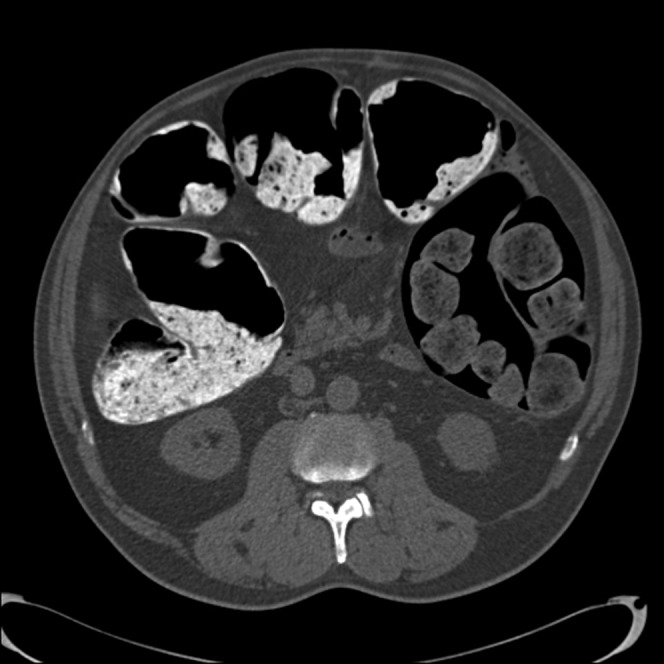

Figure 2.

An 85-year-old male with rectal bleeding. Axial CT colonographic image demonstrating a large volume of retained stool in the ascending colon (>50% anteroposterior diameter; grade 4) and untagged stool in the descending colon (grade 1).

Colonoscopic correlation was not sought owing to the relatively small number of positive findings in terms of polyp or cancer detection and the fact that the study was not formally designed to investigate the accuracy of the CTC bowel preparation as an end point.

Patient experience

Before undertaking their examination, consecutive patients were asked to complete a questionnaire relating to their experiences of the bowel preparation regime.

Patients were asked to declare whether they had taken all of the preparation components as detailed by the preparation regime protocol. Patients were assured that they would not be excluded from having their examination if they had failed to adhere to the instructions or were unable to tolerate the preparation owing to side-effects.

The questionnaire was designed using questions previously used in evaluation of bowel preparation [20-22], using a Likert scale with seven points employed for each question [23]. A variety of potential side-effects from the bowel preparation were interrogated as follows: general disruption to daily life, overall discomfort, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, anal irritation, thirst, hunger, nausea and vomiting. Patients were asked to rate how severe each symptom was, with 1 equalling no symptoms experienced and a score of 7 equalling extreme symptoms. Patients were finally asked whether they would take the bowel preparation again if required.

Statistical analysis

For all statistical comparisons, any difference associated with a two-tailed p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Age and sex distributions between the groups were analysed using the Mann–Whitney U-test and χ2 test, respectively.

For the analysis of the volumes of residual stool and fluid, as well of the quality of tagging, we applied ordinal regression analysis and the generalised estimating equation to allow for clustering and dependency of data (multiple segments per patient) and compared the groups using a non-parametric analysis of variation (ANOVA) test.

Further scalar data including patient responses to bowel preparation side-effects were analysed using the Mann–Whitney U-test. The χ2 test was applied to the question regarding whether the patient would take the bowel preparation again.

Results

The diagnostic arm sex breakdown was as follows: the ratio of males to females was 17:33 for Regime 1 and 16:34 for Regime 2. Mean ages for Regimes 1 and 2 were 74 [standard deviation (SD) 13.5] and 71 (SD 12.1) years old, respectively.

The ratio of males to females for patients returning questionnaires was 21:29, 15:35 and 22:28 for Regime 1, Regime 2 and barium enema, respectively. Mean ages for Regimes 1, 2 and the barium enema group were 71 (SD 16.4), 68 (SD 13.5) and 65 (SD 12.8) years old, respectively.

No statistical significance was reached between these demographic data.

Residual stool volume

Regime 1 produced 271/300 (90.3%) colonic segments with no or only scattered stool (grade 1). Regime 2 yielded 195/300 (65.0%) colonic segments with the same optimal preparation (p<0.005).

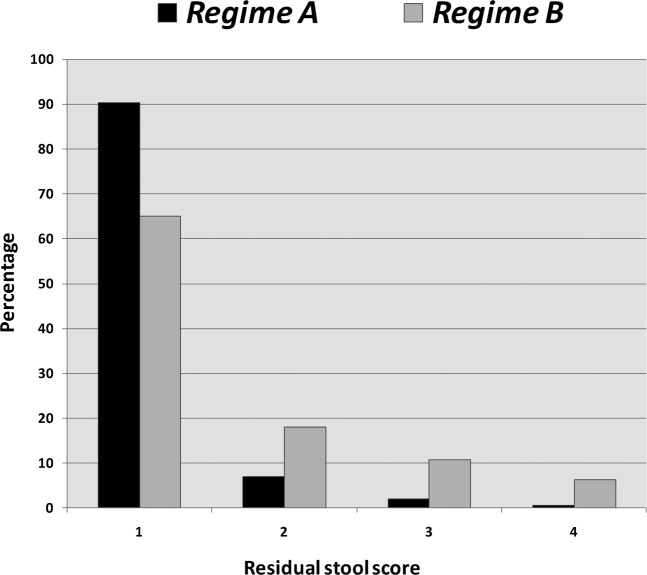

There were 51/300 (17.0%) segments rated grades 3 or 4 (25–50% and >50% anteroposterior diameter of stool) with Regime 2 and 8/300 (2.67%) with Regime 1 (p<0.005). Figure 3 illustrates the stool volume scores achieved by both regimes.

Figure 3.

Residual stool volume grades assigned to segments produced by each CT colonography bowel preparation regime.

Per segment analysis between the two preparation regimes showed significantly reduced volumes (p<0.05) of stool in all colonic segments with Regime 1 except for the rectum (p=0.135).

Analysing for variability in residual stool volume between colonic segments prepared using Regime 1 yielded statistically significant differences between the volume of residual stool in the sigmoid colon and the ascending and transverse colonic segments (p=0.011 and 0.021, respectively). No such differences were shown between segments prepared using Regime 2.

Stool tagging

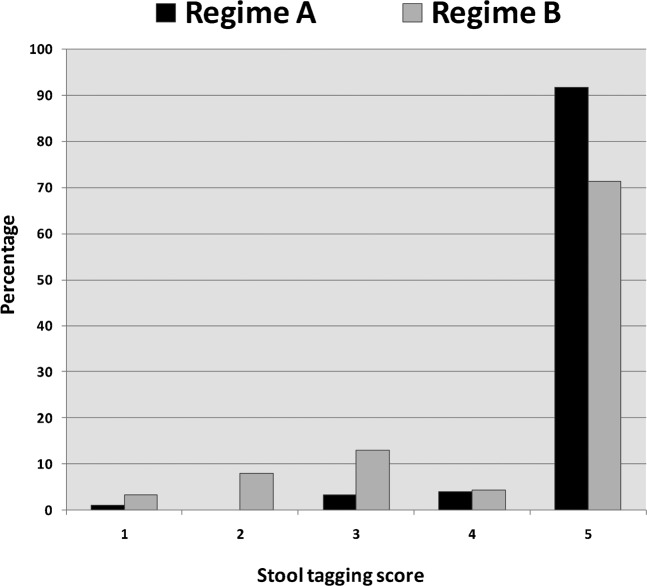

The number of segments rated grade 5 (75–100% of stool tagged) was 275/300 (91.7%) and 214/300 (71.3%) for Regimes 1 and 2, respectively (p<0.05).

There were 13/300 (4.33%) segments with stool tagging grades of 1–3 (none, 0–25% and 25–50% tagged) for Regime 1 compared with 62/300 (20.7%) for Regime 2 (p<0.005). Figure 4 illustrates the stool tagging scores achieved by both regimes.

Figure 4.

Stool tagging scores assigned to colon segments produced by each CT colonography bowel preparation regime.

Per segment analysis yielded statistically significantly superior stool tagging with Regime 1 across all colonic segments compared with Regime 2, with the exception of the caecum (p=0.106).

No significant difference in tagging quality existed between colonic segments prepared using Regime 1. With Regime 2 there was significantly poorer tagging quality between the sigmoid and rectum and the more proximal colonic segments (ascending/caecum vs sigmoid and rectum p<0.005), with more segments containing completely untagged faeces (grade 1; 8/100 for sigmoid and rectum and only 1/100 for caecum and ascending colon).

Residual fluid volume

The number of colonic segments that exhibited the least retained fluid volume and thus the best preparation (grade 1) was 56/300 and 18/300 (18.7% and 6%) for Regimes 1 and 2, respectively. The commonest score assigned to colonic segments was 2 (<25% anteroposterior diameter of residual fluid) and was found in 180/300 and 218/300 segments for Regimes 1 and 2, respectively.

ANOVA analysis shows statistically lower fluid volume scores for Regime 1 across all colonic segments (p=0.008). Per segment analysis showed no significant difference in fluid volume scores except for the descending colon (p=0.036).

Fluid tagging

Homogeneous tagging of residual fluid (grade 3) was achieved in 94.7% of colon segments with Regime 1 and 98.3% of colons with Regime 2. No statistical significance existed between preparation regimes or between colonic segments within regimes.

Patient experience

Patients rated a variety of symptoms and side effects relating to the bowel preparation for both CTC regimes and a cohort of patients undergoing barium enema examination. The median score and interquartile ranges assigned to each side effect for each of the three bowel preparations is shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Patient questionnaire responses: median and interquartile ranges.

| Regime | Disruption | Discomfort | Diarrhoea | Thirst | Hunger | Headache | Vomiting | Nausea | Abdominal pain | Bloating | Anal irritation |

| 1 | 3, 3 | 2, 2 | 3.5, 4 | 1, 2 | 3, 4 | 3, 2 | 1, 0 | 1, 0 | 1, 2 | 1, 1 | 1, 3 |

| 2 | 2, 2 | 2, 2 | 3, 4 | 2, 2 | 1, 1 | 1, 1 | 1, 0 | 1, 1 | 1, 1 | 1, 1.5 | 1, 1 |

| Barium enema | 5, 3 | 4, 3 | 7, 3 | 3, 3 | 2, 4 | 1, 3 | 1, 0 | 1, 0 | 1, 1 | 1, 2 | 1, 1 |

Disruption to everyday life: no significant difference was shown between the CTC regimes. Significantly worse for barium enema preparation (p<0.005 for both CTC regimes).

General discomfort: no significant difference was shown between the CTC regimes. Significantly worse for barium enema preparation (p<0.005 for both CTC regimes).

Diarrhoea: barium enema preparation was rated significantly more burdensome than either of the CTC preparations (p<0.0001 for both CTC regimes). No difference existed between the CTC regimes.

Thirst: significantly less thirst was experienced by patients taking Regime 1 compared with barium enema preparation (p=0.021). There was no difference between the CTC regimes.

Hunger: significantly less hunger was experienced by patients taking Regime 2 compared with both Regime 1 and the barium enema preparation (p=0.0002 and p=0.0013). No difference existed between Regime 1 and barium enema.

Headache: significantly more patients rated headache as a significant side effect with the barium enema preparation compared with Regime 2 (p=0.042), but no such significance existed compared with Regime 1 or between the CTC regimes.

No significant difference existed between the bowel preparations for the following side effects: nausea, vomiting, anal irritation and bloating.

Refusal to take bowel preparation again: fewer patients would refuse to take the bowel preparation again with Regime 2 (2/50) compared with Regime 1 (5/50) and the barium enema (8/50) preparation, but this was not statistically significant.

Discussion

We have shown that a simple bowel preparation regime incorporating a mild laxative and three doses of each of iodinated contrast and barium taken over 2 days prior to examination produces a very well-prepared colon that is well tolerated by patients.

Much work continues in attempting to establish a bowel preparation regime that balances the need for a colon with as little residual material as possible for accurate and safe exclusion of colorectal neoplasia and polyps with the smallest side effect profile to ensure a high acceptability to patients, who are often asymptomatic.

The use of a low-residue diet is a simple and effective way of reducing the volume of residual faecal material [24], with no difference in patient acceptance [25]. The exact timing of when to ask patients to commence a low-residue diet has yet to be established [26,27].

The use of tagging agents to increase the conspicuity of residual material is an established method of reducing the need for full cathartic bowel preparation. Several of the major studies undertaken to establish the accuracy of CTC as a tool for polyp and cancer detection [8,28] used full purgative bowel preparation for bowel cleansing in combination with both barium and iodine residue tagging.

The optimum tagging agent is yet to be established with proponents of both barium- and iodine-based agents. Likewise, the optimal timing and volumes of these agents remains to be optimised. Some authors have concluded that barium preferentially tags solid faecal material, leaving appreciable volumes of colonic fluid untagged [18]. Larger volumes of administered barium seem to tag a greater proportion of colonic fluid, but with layering [19]. The hyperosomolar properties of Gastrografin may to some degree allow liquidisation of stool and more homogeneous incorporation of tagging agent. There is clearly complex interplay between the volumes, concentrations and timings of administered tagging agent with the volumes of ingested fluid and diet, and the ultimate appearance at CTC.

Minimal preparation regimes vary greatly. The term itself encompasses a wide range of differing practices across institutions in terms of the quantity of tagging agents ingested by the patient, the timing and frequency of their ingestion, and the addition of other laxatives and implementation of dietary restrictions. The ideal regime should be simple and reproducible with small volumes of tagging agents and minimal side-effects.

In our study, the proportion of colonic segments that contained no residual stool was strikingly different between the longer, mixed preparation regime and the shorter 24 h regime consisting of only iodinated contrast (90.3% vs 65.0%). The explanation of this is likely to be multifactorial and could be owing to the incorporation of a mild laxative with Regime 1 as well as the longer preparation period. This is borne out by the observation that only 2.67% of segments exhibited stool occupying >25% of the luminal diameter with Regime 1 compared with 17.0% of segments with Regime 2.

When tagging-only regimes are used for CTC it is important that there is thorough and homogeneous incorporation of the tagging agent with the faeces, without untagged faecal remnants. Inadequate tagging could lead to an examination where detection and exclusion of mucosal pathology is difficult. In our study there was a significantly higher number of colonic segments containing faecal residue that was untagged or only partially (<25%) tagged: 3/300 (1.0%) for Regime 1 and 23/300 (7.7%) for Regime 2. The 24 h tagging-only regime showed a significant difference in tagging homogeneity between the better tagged proximal colonic segments and the distal colonic segments. This raises the possibility that a 24 h preparation protocol is insufficient time in some patients to ensure homogeneous tagging in the more distal colonic segments where the majority of neoplastic lesions arise.

Both regimes showed thorough homogeneous tagging of residual fluid. This is likely to be attributable to both regimes using iodinated contrast, which preferentially tags fluid. There was a significant difference in the volume of residual fluid between the two tagging regimes. The addition of a mild stimulant laxative to Regime 1, leading to lower residual colonic fluid volumes, presumably accounts for this.

The side effects rated most burdensome by patients undergoing CTC were diarrhoea and general disruption to daily life. Importantly, these were tolerated equally well between the two regimes, with similar median scores and interquartile ranges. The addition of a mild laxative to Regime 1 did not have a significant impact on the amount of diarrhoea experienced by patients, but is likely to have a positive effect on image quality in terms of stool softening, allowing greater homogeneity of tagging and reducing both colonic faeces and fluid.

Of the 11 side effects detailed in the questionnaire, the only symptom for which the experience of patients in the 2 CTC cohorts differed was hunger, with patients undertaking the longer, mixed regime experiencing significantly more hunger than those in the 24 h tagging-only group. Both cohorts undertook the same low-residue diet for the same 72 h period before their examination and in terms of the volumes of tagging material ingested Regime 1 was significantly higher (750 ml of diluted barium and 60 ml iodinated contrast in total vs just 100 ml of iodinated contrast with Regime 2). The difference in hunger symptoms is therefore difficult to explain.

There was a marked difference between many side effects experienced by the barium enema cohort compared with the CTC cohorts, including diarrhoea, disruption to daily life and discomfort. Diarrhoea was, unsurprisingly, particularly poorly tolerated, with a median score of 7, equating to extreme symptoms.

There was no difference between the numbers of patients in the CTC cohorts who would refuse to take the bowel preparation again, which is a good surrogate marker for how well tolerated the preparation was overall. This observation is particularly relevant in the context of screening, where patients are often asymptomatic and adherence to the protocol is important to maintain a successful programme.

This study has some weaknesses. There were an insufficient number of polyps identified during the study for any meaningful interpretation regarding accuracy of either technique. The technical aspect of the study was a retrospective analysis of completed CTC studies. Potential bias was minimised by blinded evaluation of the preparation regime by two readers with consensus agreement for any discrepancies. Furthermore, different cohorts were examined on different sites using different CT scanners, with manual air insufflation for colonic distension for Regime 1 and automated CO2insufflation for Regime 2.

Conclusion

The faecal tagging regime consisting of a 2 day preparation with small volumes of barium and iodinated contrast and a mild laxative yielded colons that were significantly better prepared than a 24 h iodinated contrast-only regime, with no significant difference in patient tolerance.

References

- 1.Buccicardi D, Grosso M, Caviglia I, Gastaldo A, Carbone S, Neri E, et al. CT colonography: patient tolerance of laxative free fecal tagging regimen versus traditional cathartic cleansing. Abdom Imaging 2011;36:532–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nagata K, Okawa T, Honma A, Endo S, Kudo SE, Yoshida H. Full-laxative versus minimum-laxative fecal-tagging CT colonography using 64-detector row CT: prospective blinded comparison of diagnostic performance, tagging quality, and patient acceptance. Acad Radiol 2009;16:780–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harewood G, Wiersema M, Melton L. A prospective, controlled assessment of factors influencing acceptance of screening colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:3186–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ristvedt S, McFarland E, Weinstock L, Thyssen E. Patient preferences for CT colonography, conventional colonoscopy and bowel preparation. Am J Gastroenterol 2003;98:578–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Belsey J, Epstein O, Heresbach D. Systematic review: adverse event reports for oral sodium phosphate and polyethylene glycol. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009;29:15–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Svensson M, Svensson E, Lasson A, Hellstrom M. Patient acceptance of CT colonography and conventional colonoscopy: prospective comparative study in patients with or suspected of having colorectal disease. Radiology 2002;222:337–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gluecker T, Johnson C, Harmsen W, Offord K, Harris A, Wilson L, et al. Colorectal cancer screening with CT colonography, colonoscopy and double-contrast barium enema examination: prospective assessment of patient perspectives and preferences. Radiology 2003;227:378–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim D, Pickhardt P, Taylor A, Leung W, Winter T, Hinshaw J, et al. CT colonography versus colonoscopy for the detection of advanced neoplasia. N Engl J Med 2007;357:1403–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jensch S, de Vries AH, Pot D, Peringa J, Bipat S, Florie J, et al. Image quality and patient acceptance of four regimens with different amounts of mild laxatives for CT colonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2008;191:158–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lefere P, Gryspeerdt S, Dewyspelaere J, Baekelandt M, Van Holsbeeck B. Dietary fecal tagging as a cleansing method before CT colonography: initial results—polyp detection and patient acceptance. Radiology 2002;224:393–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zalis M, Perumpillichira J, Del Frate, Hahn P. CT colonography: digital subtraction bowel cleansing with mucosal reconstruction: initial observations. Radiology 2003;226:911–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Callstrom M, Johnson C, Fletcher J, Reed J, Ahlquist D, Harmsen W, et al. CT colonography without cathartic preparation: feasibility study. Radiology 2001;219:693–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson C, Manduca A, Fletcher J, MacCarty R, Carston M, Harmsen W, et al. Non-cathartic CT colonography with stool tagging: performance with and without electronic stool subtraction. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2008;190:361–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liedenbaum M, de Vries A, Gouw C, Van Rijn A, Bipat S, Dekke E, et al. CT colonography with minimal bowel preparation: evaluation of tagging quality, patient acceptance and two iodine-based preparation schemes. Eur Radiol 2010;20:367–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liedenbaum M, Denters M, Zijta F, Van Ravesteijn V, Bipat S, Vos F, et al. Reducing the oral contrast dose in CT colonography: evaluation of faecal tagging quality and patient acceptance. Clin Radiol 2011;66:30–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taylor S, Halligan S, Burling P, Bassett P, Bartram CI. Intra-individual comparison of patient acceptability of multidetector-row CT colonography and double-contrast barium enema. Clin Radiol 2005;60:207–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mahgerefteh S, Fraifeld S, Blachar A, Sosna J. CT colonography with decreased purgation: balancing preparation, performance and patient acceptance. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2009;193:1531–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lefere P, Gryspeerdt S, Marrannes J, Baekelandt M, Van Holsbeeck B. CT colonography after fecal tagging with a reduced volume of barium. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2005;184:1836–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taylor S, Slater A, Burling D, Tam E, Greenhalgh R, Gartner L, et al. CT colonography: optimisation, diagnostic performance and patient acceptability of reduced-laxative regimens using barium-based faecal tagging. Eur Radiol 2008;18:32–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heymann T, Chopra K, Nunn, Coulter E, Westaby D, Murray-Lyon I. Bowel preparation at home: prospective study of adverse effects in elderly people. BMJ 1996;313:727–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jensch S, Bipat S, Peringa J, de Vries A, Heutinck A, Dekker E, et al. CT colonography with limited bowel preparation: prospective assessment of patient experience and preference in comparison to optical colonoscopy with cathartic bowel preparation. Eur Radiol 2010;20:146–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Gelder R, Birnie E, Florie J, Schutter M, Bartelsman J, Snel P, et al. CT colonography and colonoscopy: assessment of patient preference in a 5-week follow-up study. Radiology 2004;233:328–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Finstad K. Response interpolation and scale sensitivity: evidence against 5-point scales. JUS 2010;5:104–10 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee J, Ferrando J. Variables in the preparation of the large intestine for double contrast barium enema examination. Gut 1984;25:69–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lindenbaum M, Denters M, de Vries A, van Ravesteijn V, Bipat S, Vos F, et al. Low-fiber diet in limited bowel preparation for CT colonography: influence on image quality and patient acceptance. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2010;195:W31–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iannaccone R, Laghi A, Catalano C, Brink J, Mangiapane F, Trenna S, et al. Computed tomographic colonography without cathartic preparation for the detection of colorectal polyps. Gastroenterology 2004;127:1300–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dachmann A, Dawson D, Lefere P, Yoshida H, Khan N, Cipriani N, et al. Comparison of routine and unprepped CT colonography augmented by low fibre diet and stool tagging: a pilot study. Abdom Imaging 2007;32:96–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson C, Chen M, Toledano A, Heiken J, Dachman A, Kuo M, et al. Accuracy of CT colonography for detection of large adenomas and cancers. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1207–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]