Abstract

Objectives

The aim of this study was to evaluate the normal anatomy of the thoracic duct and cisterna chyli obtained by axial and multiplanar reformation (MPR) images of 1 mm slice thickness using multidetector row CT (MDCT).

Methods

We evaluated the ability of MDCT to examine the normal anatomy of the thoracic duct and cisterna chyli. The axial and coronal images of thoracoabdominal MDCT images obtained in 50 patients (20 females and 30 males; mean age, 63.5 years; range, 32–81 years) were reviewed between January and October 2005. We excluded patients with malignant neoplasms, inflammation or vascular diseases (e.g. aortic aneurysm, aortic dissection) and those with a history of thoracoabdominal surgery. The thoracic duct was divided into three anatomical sections: the upper, middle and lower. We evaluated the degree of visualisation and the maximum size of the thoracic duct. We also evaluated the degree of visualisation, maximum size, configuration and location of the cisterna chyli.

Results

Visualisation of the thoracic duct and cisterna chyli was almost 100% on axial and coronal images. The lower section of the thoracic duct was most clearly visualised among the three sections. There was little difference in the maximum size of the thoracic duct among the three sections. The cisterna chyli was most frequently located at the Th12 or L1 level, and the most common type was the “straight thin tube type”.

Conclusion

Axial and MPR images of 1 mm slice thickness using MDCT can clearly depict the thoracic duct and cisterna chyli.

The thoracic duct is the main collecting vessel of the lymphatic system. It drains three-quarters of the lymph in the body into the venous blood stream. The lymphatic system, which connects the lymphatics of various organs, is an important network for the circulation of fluid throughout the body [1,2].

The lymph from the lower limb finally terminates at the para-aortic nodes. They join with the lymph from the viscera of the pelvis and form bilateral lumbar trunks. The intestinal trunks consist of large lymphatic vessels that receive lymph from the stomach, intestine, pancreas and spleen. The cisterna chyli receives the lymph from bilateral lumbar trunks, along with the intestinal trunks. Some authors prefer the descriptive phrase “abdominal confluence of the lymphatic trunks”, forming the origin of the thoracic duct. The thoracic duct frequently drains into the junction of the left jugular and subclavian veins [1,2]. The lymphatic system is involved in various pathological conditions, including neoplastic diseases that can result in disturbances of lymphatic flow. Furthermore, laceration of the thoracic duct sometimes occurs after surgery (for example, oesophagectomy, pneumonectomy and spine surgery), and these result in incurable chylothorax. Therefore, it is necessary to recognise its precise location before surgery.

It is difficult for conventional CT and MRI to visualise the lymphatic system because of its thin and complicated structures. Lymphangiography and lymphoscintigraphy were originally the only methods to visualise the lymphatic system, but recently MR lymphography has become feasible for visualising the lymphatic system. Currently, thin-slice and multiplanar reformation (MPR) images using multidetector row CT (MDCT) enable the understanding of detailed anatomy of various organs. Recently, there have been some reports regarding the evaluation of the thoracic duct and the cisterna chyli by using MDCT [3,4].

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the normal anatomy of the thoracic duct and the cisterna chyli by axial and MPR images of 1 mm slice thickness using MDCT.

Anatomical considerations

The cisterna chyli is the abdominal origin of the thoracic duct, and it receives the bilateral lumbar lymphatic trunks. It is located in the retrocrural space, to the right side and behind of the abdominal aorta. It is at the level of the lower border of the Th12 vertebral body or L1–2 vertebrae, and it lies lateral to the right crus of the diaphragm [5-7].

The thoracic duct starts from the cisterna chyli, and it is at the level of the second or third lumbar vertebra. It then enters the thorax through the aortic hiatus of the diaphragm and ascends in the posterior mediastinum, between the descending thoracic aorta on the left and the azygos vein on the right. When it reaches the level of the fifth thoracic vertebral body, it gradually inclines to the left side and enters the superior mediastinum. It first crosses anteriorly by the aortic arch, and it runs posterior to the left subclavian artery, and forms an arch. Finally, the duct terminates by opening into the junction of the left subclavian and jugular veins. However, the duct may open into either of the great veins near the junction or it may divide into a number of smaller vessels before termination. In adults, the thoracic duct varies in length from 38 to 45 cm. It is approximately 3–5 mm in diameter at its commencement, but diminishes in calibre at the mid-thoracic level and then slightly dilates before its termination [2].

Methods and materials

Subjects

We reviewed contrast-enhanced thoracoabdominal MDCT obtained in 50 patients (20 females and 30 males; mean age, 63.5 years; range, 32–81 years) in Oita University Hospital between January and October 2005 by using 32- or 64-MDCT (Aquilion; Toshiba Medical Systems Corporation, Otawara, Japan). This retrospective study was conducted in accordance with the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki. The local institutional review board approved the study and waived the requirement for obtaining informed consent. We excluded patients with malignant neoplasms, inflammatory diseases or vascular diseases (e.g. aortic aneurysm, aortic dissection) and those with a history of thoracoabdominal surgery.

Imaging techniques

The patients fasted for at least 3 h before contrast-enhanced CT examination, and were examined in the supine position with the arms above the head. The CT images were scanned with intermittent breath-holding after maximum inspiration. Contrast-enhanced MDCT was performed on 16- or 32-detector row CT scanner. The CT parameters used were 120 kVp, a slice thickness of 1.0 mm, a rotation time of 0.5 s and a pitch of 0.8/0.9. The total amount of contrast medium with 300–370 mg ml−1 was 100–150 ml (2.0 ml kg−1), and it was injected using a dual injector (Nemoto-kyorindo, Tokyo, Japan) at a rate of 2–3 ml s−1 without a saline-flush technique. Scanning was performed after a delay of 70–150 s according to each protocol in various MDCT studies. The raw MDCT data were reconstructed by a workstation (Aquarius Net Station; TeraRecon, Inc., Foster City, CA).

Imaging analysis

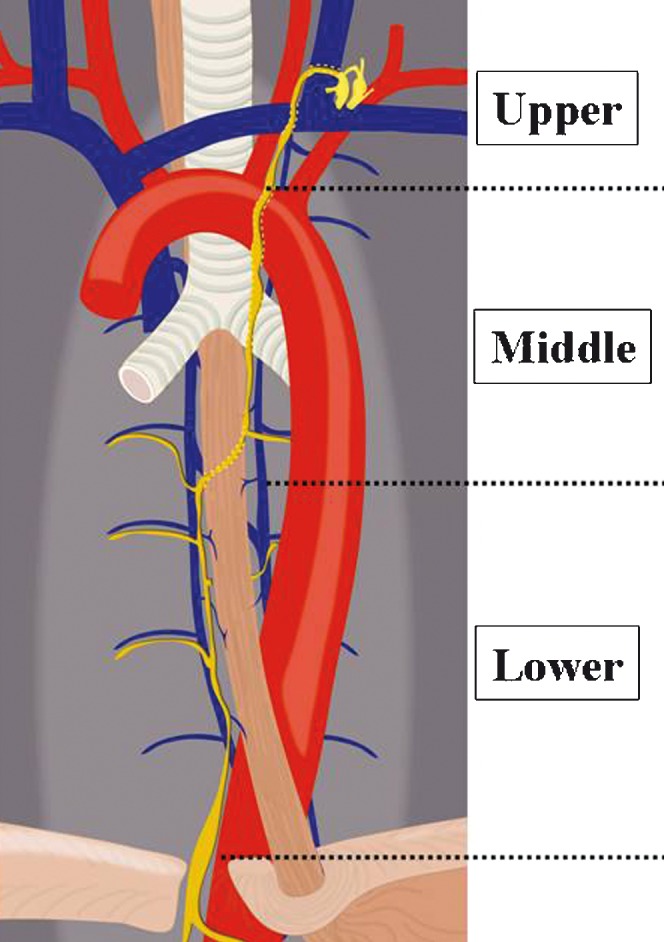

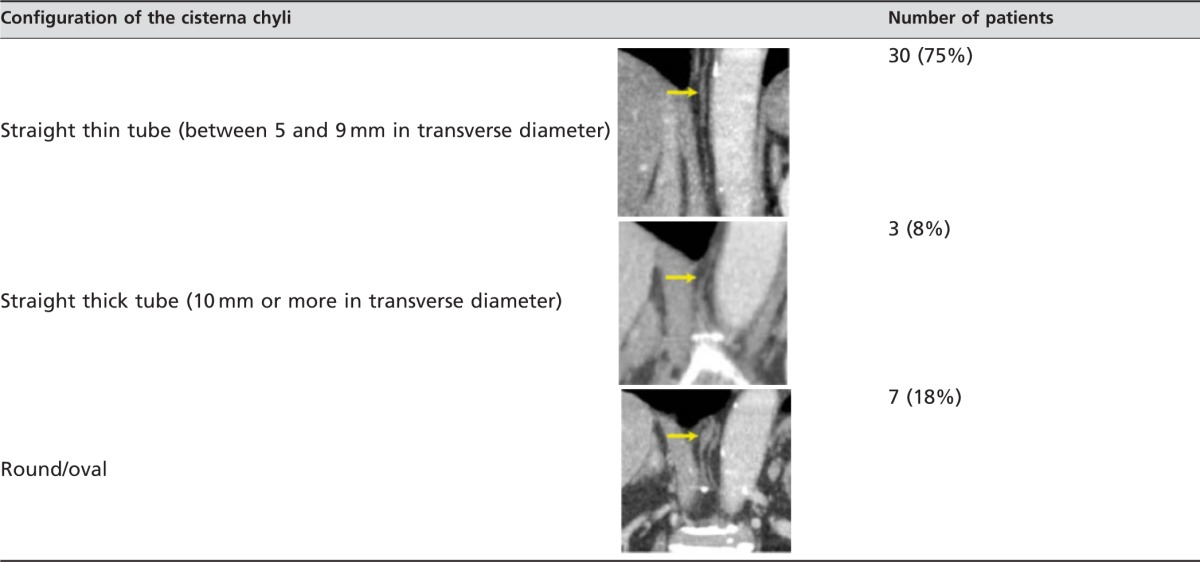

The CT images were independently reviewed by two radiologists (MK and MS) who have approximately 7 and 14 years of experience in CT imaging interpretation, respectively. The axial and coronal reconstructed images (window level/window width: 50/500) were used for evaluation of normal anatomy of the thoracic duct and the cisterna chyli. In this study, the thoracic duct was divided into three anatomical sections (Figure 1) as follows: (i) lower section: the portion ascending along the right side of the oesophagus, from the level of the aortic hiatus of the left hemidiaphragm to the level the thoracic duct turning to the left side of the oesophagus (the Th5 level); (ii) middle section: the level where the thoracic duct inclines to the left side (the Th5 level) from the right side of the oesophagus to the level of the aortic arch; and (iii) upper section: the portion above the level of the aortic arch. We defined the thoracic duct as a soft-tissue attenuating structure in the posterior mediastinum, contiguous to the cisterna chyli, and the cisterna chyli was identified as a tubular structure with soft-tissue attenuation between the abdominal aorta and the right crus of the diaphragm. We evaluated the visualisation and maximum size of the thoracic duct, and evaluated the visualisation, maximum size, configuration and location of the cisterna chyli. For the degree of visualisation of the thoracic duct and cisterna chyli, two reviewers rated the confidence level using a 3-point scale as follows: 1, minimal (not or only barely identified); 2, partial (partially identified); and 3, complete (entirely and clearly identified). The configuration of the cisterna chyli was classified into three types: a straight thin tube (5–9 mm in transverse diameter), a straight thick tube (≥10 mm in transverse diameter) and focal round or oval. These criteria for evaluation were based on a previous report by Takahashi et al [8].

Figure 1.

Schematic drawing of the three sections of the thoracic duct. The thoracic duct was divided into three anatomical sections. The lower section ascending along the right side of the oesophagus is located between the level of the aortic hiatus of the left hemidiaphragm and the level where the thoracic duct begins to turn to the left side of the oesophagus (the Th5 level). The middle section is located between the level where the thoracic duct inclines to the left side (the Th5 level) from the right side of the oesophagus and the level of the aortic arch. The upper section is located above the level of the aortic arch.

In the cases where all three sections of the thoracic duct were completely visualised from the axial images, we attempted to use curved planar reconstruction images to depict its entire appearance, but evaluation of their images was not executed.

Data analysis

For the degree of visualisation of the thoracic duct and cisterna chyli, interobserver agreements were quantified using kappa-statistics to establish the reliability of imaging interpretation. Kappa-values were assessed as: κ≤0.20, minor agreement; κ=0.21–0.40, fair agreement; κ=0.41–0.60, moderate agreement; κ=0.61–0.80, high agreement; and κ=0.81–1.00, almost perfect agreement [9,10]. Discrepancies regarding these evaluations between the two reviewers were resolved by consensus.

Results

Thoracic duct

The thoracic duct was observed as a soft-tissue attenuating structure (mean, +15.3 HU; range, +4.5–38 HU), which was slightly lower than the arteries and veins in attenuation. It was recognised as a contiguous longitudinal tubular structure. Table 1 summarises the degree of visualisation in each anatomical section of the thoracic duct. The kappa value for interobserver variability between the two reviewers was κ=0.92, indicating almost perfect agreement. Among the three sections, the lower section showed the highest frequency (72%) for “complete” visualisation, while the upper section most frequently showed “minimal” visualisation. The portion between the level of the aortic arch and confluence to the left subclavian vein or the left jugular vein was identified as “complete” visualisation in 7 (14%) of 50 patients. The mean maximum size of the thoracic duct was evaluated in patients who showed “clear” or “partial” visualisation at each section. Its mean maximum size (longitudinal diameter × transverse diameter) was 2.8×2.3 mm (range, 1.8–4.9×1.1–2.8 mm) at the upper section (n=28), 2.5×2.1 mm (range, 1.4–4.6×1.3–3.1 mm) at the middle section (n=40) and 2.7×2.4 mm (range, 1.4–4.9×1.4–4.6 mm) at the lower section (n=43; Table 1). There was no significant difference in measurement among the three sections (p<0.01).

Table 1. Visualisation and mean maximum size of the thoracic duct in each section.

| Visualisation |

Mean maximum size |

||||

| Section | Complete | Partial | Minimal | LD | TD |

| Upper | 14% | 42% | 44% | 2.8 mm | 2.3 mm |

| Middle | 52% | 28% | 20% | 2.5 mm | 2.1 mm |

| Lower | 72% | 14% | 14% | 2.7 mm | 2.4 mm |

LD, longitudinal diameter; TD, transverse diameter.

Visualisation of the thoracic duct was evaluated in 50 patients with regard to each section. The mean maximum size was evaluated in 38 patients with upper section, 43 patients with middle section and 44 patients with lower section who showed “complete” or “partial” visualisation at each section.

Cisterna chyli

Table 2 summarises the degree of visualisation of the cisterna chyli. The kappa value for interobserver variability between the two reviewers was κ=0.88, indicating almost perfect agreement. As a result, there was “complete” visualisation in 58% (n=29/50), “partial” in 22% and “minimal” in 20% of patients. In 40 patients who showed “complete” or “partial” visualisation, the location, configuration and maximum diameter of the cisterna chyli were evaluated. The cisterna chyli was located from L1 to the inferior aspect of Th11, and its most frequent level was at Th12 (n=17, 44%), followed by L1 (n=16, 42%) and Th11 (n=5, 13%) (Table 2). Regarding the configuration of the cisterna chyli, the straight thin tube (n=30, 75%) was the most common type (Table 3). The mean maximum size (longitudinal diameter×transverse diameter×length) of the cisterna chyli was 3.8×4.0×14.1 mm (range, 1.7–7.8×1.3–6.9×3.8–30.1 mm).

Table 2. Visualisation, mean maximum size and location of the cisterna chyli.

| Visualisation | Mean maximum size | Level | |||

| Complete | 58% | LD | 3.8 mm | Th11 | 13% |

| Partial | 22% | TD | 4.0 mm | Th12 | 44% |

| Minimal | 20% | Length | 14.1 mm | L1 | 42% |

LD, longitudinal diameter; TD, transverse diameter.

Visualisation of the cisterna chyli was evaluated in 50 patients, and its maximum size and location level were evaluated in 40 patients who showed “complete” or “partial” visualisation on multidetector CT.

Table 3. Configuration of the cisterna chyli in 40 patients who showed “complete” or “partial” visualisation on MDCT.

Representative cases where the thoracic duct and cisterna chyli were able to be clearly identified on axial, coronal and curved planar reconstruction images are shown in Figures 2–4.

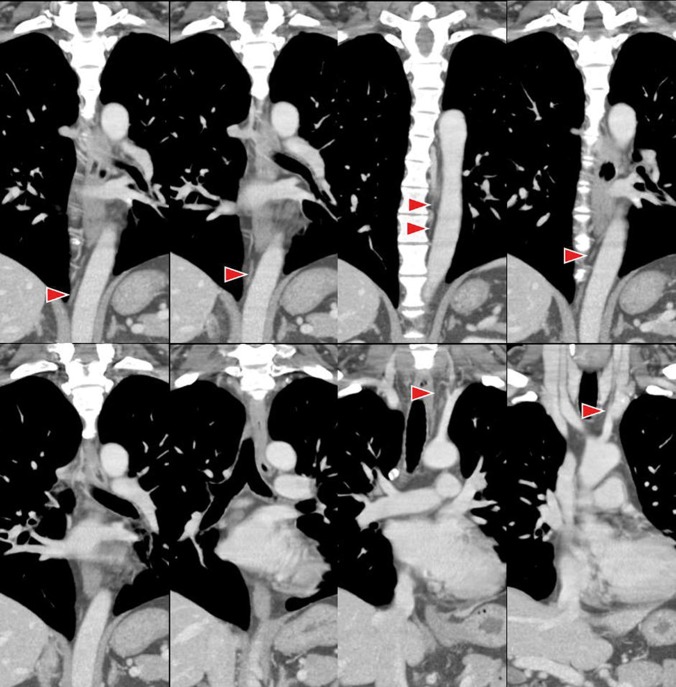

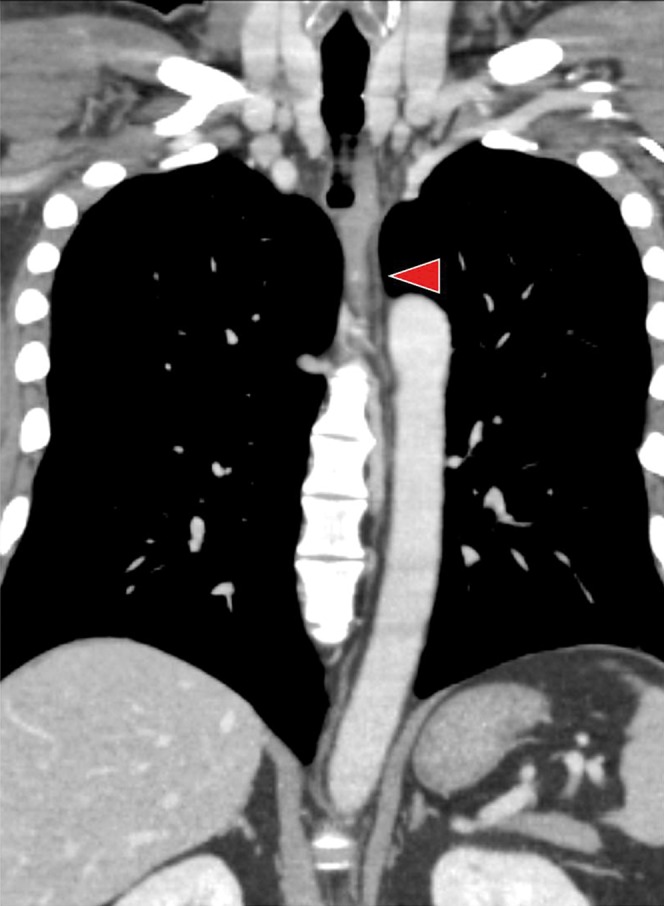

Figure 2.

Coronal multidetector row CT images of the thoracic duct in a 39-year-old male. The cisterna chyli and the thoracic duct (arrowheads) are completely visible.

Figure 4.

Curved planar reconstruction image of the thoracic duct in a 39-year-old male. The entire thoracic duct (arrowhead) was clearly visualised.

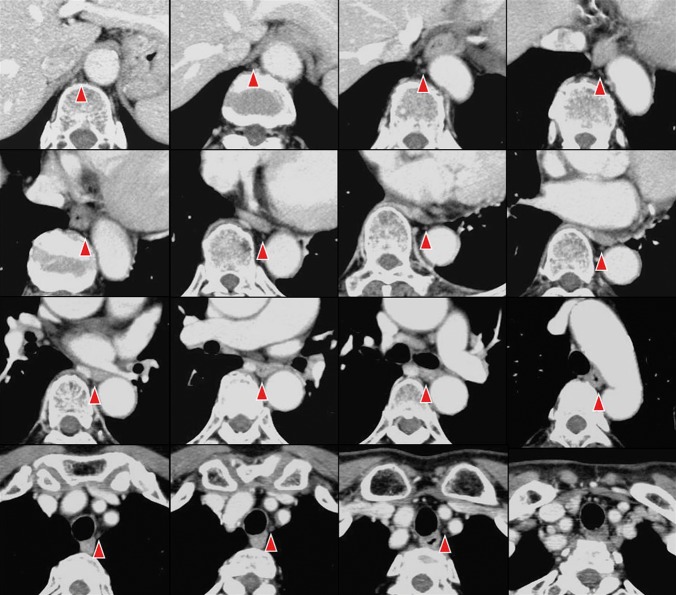

Figure 3.

Axial multidetector CT images of the thoracic duct in a 65-year-old female. The cisterna chyli and the thoracic duct (arrowheads) are completely visible.

Discussion

The lymphatic system is anatomically complicated and is difficult to visualise with current imaging modalities. Previously, conventional lymphangiography was the only technique that could obtain a detailed view of the lymphatic ducts [11]. However, lymphangiography is invasive and cannot acquire images of the entire anatomy of the lymphatic duct. Recently, there have been some reports on the evaluation of the thoracic duct or cisterna chyli using MDCT. Liu et al [3] reported a normal appearance of the distal (cervical) thoracic duct. According to their study, using MDCT, the distal thoracic duct was identified in the left side of the neck in 150 (55%) of 275 patients, and the mean diameter was 4.8 mm. Moreover, in the right side of the neck, 11 (4%) of 288 distal ducts were visualised. In the present study, however, “complete” visualisation in the upper section between the level of the aortic arch and confluence to the left subclavian vein or the left jugular vein was detected in only 14% of patients. Liu et al [3] evaluated the thoracic duct in only a portion of the confluence, and therefore the difference in visualisation frequencies between studies is probably due to the difference in range of evaluation. Low detectability for the thoracic duct in the upper section is probably due to the difficulty of differentiation between the thoracic duct and the adjacent vessels because of less fat tissue in this area. The thoracic duct is a very small organ with a complex course, and therefore accurate detection of its course, including the confluence, is difficult, even by 1-mm-slice MPR images of MDCT. To the best of our knowledge, there are few previous reports where the thoracic duct was completely evaluated (from lower to upper sections) using MDCT. Using single helical CT with a 4 mm slice thickness, Schnyder et al [12] reported that visualisation of the thoracic duct was 34%. On the other hand, use of the MRI technique for thoracic duct visualisation has previously been reported by some investigators [8,13-16]. Imaging of the lymphatic channels, especially to the thoracic duct and cisterna chyli, has been performed with heavily T2 weighted sequences of MRI. This imaging technique emphasises static fluid in fluid-containing structures, similar to MR cholangiopancreatography [13-15]. Hayashi and Miyazaki [13] reported that an entire image of the thoracic duct was depicted in all six cases with a short echo spacing 3D half-Fourier fast spin echo sequence, without use of a contrast media. More recently, the [3] protocol of MR-thoracic ductography (MRTD) was introduced by Okuda et al [16]. They reported that MRTD is non-invasive and enables identification of the configuration and anatomical variation of the thoracic duct. While MDCT images, such as those used in the present study, are thought to be superior to MRTD images in evaluating the relation between the thoracic duct and thoracic diseases such as oesophageal cancer, lung cancer and mediastinal tumours, MRTD is recommended for detailed examination when the thoracic duct cannot be sufficiently detected on contrast-enhanced MDCT, especially in a pre-operative status.

Feuerlein et al [4] reported the prevalence and characteristics of the cisterna chyli on MDCT. They reported that the cisterna chyli was found in 484 (16.1%) of 3000 patients, and the mean diameter and length of the cisterna chyli were 6.2 and 13.1 mm, respectively. The most common location was at the level of Th12/L1. Their study results were similar to those of our study. Furthermore, their report showed that patients with malignancies had a significantly (p<0.001) higher prevalence of cisterna chyli (19.4%) than patients with benign conditions (11.6%). Gollub and Castellino [5] were able to identify the cisterna chyli using single helical CT. However, they stated that a cisterna chyli larger than 6 mm in size may potentially be mistaken for an enlarged lymph node. Smith and Grigoropoulos [6] reported that visualisation of the cisterna chyli was 1.7% on single helical CT using a 5- or 7-mm slice thickness. In our study, using 1-mm slice thickness MDCT, both the thoracic duct and the cisterna chyli were identified in all cases, and visualisation of the cisterna chyli was better in our study than in the study reported by Smith and Grigoropoulos [6], although there was little difference in the maximum size, configuration and the level of the cisterna chyli.

It has been reported that chylothorax occurs by laceration of the thoracic duct after various surgeries such as oesophagectomy, pneumonectomy and spine surgery; the prevalence of laceration ranges from 0.5% to as high as 2.0%. Sachs et al [17] reported that lymphangiography and CT were useful in diagnosing laceration of the thoracic duct in 12 patients with chylothorax or chylous ascites after surgery. Therefore, recognition of the precise localisation of the thoracic duct before surgery is important to avoid iatrogenic complications. In patients with chylothorax, we recommend evaluation by MDCT but not by MRI because chylothorax showing high signal intensity cannot be differentiated from the thoracic duct. Adachi [18] confirmed thoracic duct configuration using dissections of 261 cadavers. The thoracic duct was classified into nine types based on its position on the right or left side of the descending aorta and its outflow to the right or left venous angles. Among these, the most commonly recognised was the right thoracic duct with left outflow, which was observed in 229 (88.7%) of 261 cadavers. In the present study with 50 patients, variations, except for this common type, were not observed. If this common type cannot be recognised on MDCT, the thoracic duct should be assessed by MRI, considering morphological variations when involvement of the thoracic duct in thoracic diseases is suspected.

There are limitations to our study. Firstly, the size of the thoracic duct and cisterna chyli can be affected by several factors, including the patient's physique and nutritional condition, but such factors were not evaluated in this study. Secondly, all CT images were obtained with intermittent breath-holding after maximum inspiration because of evaluation of the lung. According to a previous study that performed MR lymphography with different postures and breathing methods, the thoracic duct was most clearly visualised when using respiratory gating in the supine position [8]. Therefore, visualisation or the size of the thoracic duct may be affected by breathing conditions. Thirdly, the size of the thoracic duct and cisterna chyli was very small, and therefore accurate measurement was not easy.

In conclusion, thin-slice axial and MPR images using MDCT can sufficiently depict the lower and middle sections of the thoracic duct and the cisterna chyli.

References

- 1.Sato T, Color atlas of applied anatomy of lymphatics anatomical basis for cancer operation. 1st edn. Tokyo, Japan: Nankoudou; 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams PL, editor Gray's anatomy. 38th edn. New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone; 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu ME, Branstetter BF, 4th, Whetstone J, Escott EJ. Normal CT appearance of the distal thoracic duct. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2006;187:1615–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feuerlein S, Kreuzer G, Schmidt SA, Muche R, Juchems MS, Aschoff AJ, et al. The cisterna chyli: prevalence, characteristics and predisposing factors. Eur Radiol 2009;19:73–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gollub MJ, Castellino RA. The cisterna chyli: a potential mimic of retrocrural lymphadenopathy on CT scans. Radiology 1996;199:477–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith TR, Grigoropoulos J. The cisterna chyli: incidence and characteristics on CT. Clin Imaging 2002;26:18–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pinto SP, Sirlin CB, Andrade-Barreto OA, Brown MA, Mindelzun RE, Mattrey RF. Cisterna chyli at routine abdominal MR imaging: a normal anatomic structure in the retrocrural space. Radiographics 2004;24:809–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takahashi H, Kuboyama S, Abe H, Aoki T, Miyazaki M, Nakata H. Clinical feasibility of noncontrast-enhanced magnetic resonance lymphography of the thoracic duct. Chest 2003;124:2136–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Landis JR, Koch GG. An application of hierarchical kappa-type statistics in the assessment of majority agreement among multiple observers. Biometrics 1977;33:363–74 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hale CA, Fleiss JL. Interval estimation under two study designs for kappa with binary classifications. Biometrics 1993;49:523–34 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guermazi A, Brice P, Hennequin C, Sarfati E. Lymphography: an old technique retains its usefulness. Radiographics 2003;23:1541–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schnyder P, Hauser H, Moss A, Gamsu G, Brasch R, Bohnet J, et al. CT of the thoracic duct. Eur J Radiol 1983;3:18–23 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayashi S, Miyazaki M. Thoracic duct: visualization at nonenhanced MR lymphography—initial experience. Radiology 1999;212:598–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verma SK, Mitchell DG, Bergin D, Mehta R, Chopra S, Choi D. The cisterna chyli: enhancement on delayed phase MR images after intravenous administration of gadolinium chelate. Radiology 2007;244:791–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsushima S, Ichiba N, Hayashi D, Fukuda K. Nonenhanced magnetic resonance lymphography: visualization of lymphatic system of the trunk on 3-dimensional heavily T2-weighted image with 2-dimensional prospective acquisition and correction. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2007;31:299–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okuda I, Udagawa H, Takahashi J, Yamase H, Kohno T, Nakajima Y. Magnetic resonance-thoracic ductography: imaging aid for thoracic surgery and thoracic duct depiction based on embryological considerations. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2009;57:640–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sachs PB, Zelch MG, Rice TW, Geisinger MA, Risius B, Lammert GK. Diagnosis and localization of laceration of the thoracic duct: usefulness of lymphangiography and CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1991;157:703–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adachi B. Der ductus thoracicus der Japaner. Kihara T, Das lymphgefässsystem der Japaner. Tokyo, Japan: Kenkyusha; 1953. pp. 1–83 [Google Scholar]