Abstract

Fas apoptosis inhibitory molecule (FAIM) was originally cloned as an inhibitor of Fas-mediated apoptosis in B cells that has been reported to affect multiple cell types. Recently, we found that FAIM enhances CD40L-mediated signal transduction, including induction of IFN regulatory factor (IRF)4, in vitro and augments plasma cell production in vivo. These results have keyed interest in the regulation of FAIM expression, about which little is known. Here, we show that Faim is regulated by IRF4. The Faim promoter contains three IRF binding sites, any two of which promote Faim expression. Faim promoter activity is lost following mutation of all three IRF binding sites, whereas activity of the full promoter is enhanced by concurrent expression of IRF4. In stimulated primary B cells, IRF4 expression precedes FAIM expression, IRF4 binds directly to the Faim promoter, and loss of IRF4 results in the failure of stimulated Faim up-regulation. Finally, FAIM is preferentially expressed in germinal center B cells. Taken together, these results indicate that FAIM expression is regulated through IRF4 and that this most likely occurs as part of germinal center formation. Because FAIM enhances CD40-induced IRF4 expression in B cells, these results suggest that induction of FAIM initiates a positive reinforcing (i.e., feed-forward) system in which IRF4 expression is both enhanced by FAIM and promotes FAIM expression.

Fas apoptosis inhibitory molecule (FAIM)3 was cloned via differential display from primary B cells whose CD40-induced Fas sensitivity was reversed by BCR engagement (1). The Faim gene is located at 9f1 in mice (and at the syntenic region 3q22 in humans) and encodes an ~1.2-kb transcript that produces a 179-aa protein of ~20 kDa (1, 2). FAIM contains a highly evolutionarily conserved sequence (from worm to fly to mouse to human) that is arranged in a unique β sandwich structure and contains no known effector motifs (3).

True to its original appellation, FAIM expression opposes death receptor-induced apoptosis in murine B cells and in other cell types in other species (1, 4, 5). Recently, Lam and colleagues reported that FAIM-null mice are unusually sensitive to Fas-mediated apoptosis within the B cell, T cell, and hepatocyte cell populations, confirming that FAIM plays a nonredundant role in protection against Fas killing (6). Beyond apoptosis, FAIM influences signaling produced by nerve growth factor/TNF family members in B cells and in neuronal cells. Thus, we showed that B cell signaling resulting from CD40 triggering, but not from other stimuli, is increased by FAIM with respect to NF-κB activation, B cell lymphoma-6 (BCL-6) loss, and IFN regulatory factor (IRF)4 expression (7). Furthermore, in keeping with these effects, FAIM expression produces increased plasma cell differentiation in vivo (7). Comella and colleagues showed that FAIM increases (and knockdown of FAIM decreases) PC-12 cell signaling resulting from nerve growth factor receptor triggering in terms of NF-κB activation and neurite outgrowth (8). These results taken together have led to great interest in the means by which FAIM expression is regulated, which until now has not been explored. Here, we report analysis of the murine Faim promoter region and show that FAIM, which enhances IRF4 expression, is in turn positively regulated through IRF4, and that FAIM is expressed in germinal center B cells.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Male BALB/cByJ mice at 8–14 wk of age were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. Mice were housed at least 1 wk before experimentation. Germ-line-deleted IRF4-null mice were produced by crossing previously described mice in which the IRF4 locus is flanked by loxP and frt sites (9) with Flp-recombinase-expressing mice to eliminate IRF4 in all embryonic cells. The phenotype of these mice matches the known characteristics of IRF4 knockout mice (10). Mice were cared for and handled in accordance with National Institutes of Health and institutional (The Feinstein Institute for Medical Research) guidelines.

B cell culture

Mouse splenic B2 cells were obtained by negative selection with anti-Thy1.2 Ab and rabbit complement, as previously described (4). Isolated B2 cells were >95% B220+. For IRF4-null mice and their littermate control mice, follicular B cells were stained with anti-B220-PerCP and anti-CD23-PE and then sort-purified as B220+CD23high cells using an Influx instrument (BD Biosciences) to avoid marginal zone B cells, which are increased in IRF4 knockout animals. A20 B lymphoma cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. B cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FCS, 10 mM HEPES, 2 mM l-glutamine, 0.1 mg/ml penicillin and streptomycin, and 50 µM 2-ME.

Cell sorting

Male BALB/cByJ mice at 8–14 wk of age were i.p. immunized with 20 µg of 2,4,6-trinitrophenyl-keyhole limpet hemocyanin g(TNP-KLH; Biosearch Technologies) in alum (Pierce). At 10–14 days after immunization, splenic tissue was obtained. B cells were first pre-purified by MACS column using CD43-biotin and streptavidin microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec), after which B cells were stained with peanut agglutinin (PNA)-FITC, B220-PE, and GL7-Alexa 647. Follicular B cells and germinal center B cells were sort-purified on an Influx instrument; germinal center B cells were sorted as B220+PNAhighGL7high cells, whereas follicular B cells were sorted as B220+PNAlowGL7low cells.

Gene expression

Total RNA was extracted using Ultraspec reagent (Biotecx) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, reverse transcribed, amplified by real-time PCR, and normalized to expression of β2-microglobulin, as previously described (11). The sequences of the primer sets are shown in Table I.

Table I.

Oligonucleotide sequences used in this studya

| Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|

| Quantitative PCR | |

| β2-microglobulin (forward) | CTGACCGGCCTGTATGCTAT |

| β2microglobulin (reverse) | TTTTCCCGTTCTTCAGCATT |

| FAIM (forward) | TGCAATGGTCAGAAAATGGA |

| FAIM (reverse) | CGCTGCTCACAGCTTTTATG |

| IRF4 (forward) | CTACCCCATGACAGCACCTT |

| IRF4 (reverse) | CCAAACGTCACAGGACATTG |

| AID (forward) | CAGGAAGCTGAGGCAGGAGG |

| AID (reverse) | TCATTTCCTTGCCACGGTCTT |

| ChIP assay: Sequence | |

| λ3′E promoter (forward) | CTTGAGAGTCCACAAGCTAAA |

| λ3′E promoter (reverse) | CTGCTAATGGACTTGGTTTC |

| FAIM promoter (forward) | AAAATCTCTCATTGGTTCGTTCC |

| FAIM promoter (reverse) | ACAAACACACAACCACTGAATTG |

| Cloning into pGL | |

| FAIM promoter −598-KpnI (forward) | CGGGGTACCCCGCACGACCTCACCCAGGATAACTAAACGCCC |

| FAIM promoter −1631-KpnI (forward) | CGGGGTACCCCGCATTTGCACAAAACCTATATGCCCAGCCCC |

| FAIM promoter XhoI (reverse) | ATACCGCTCGAGCGGTCAACGAGACCCCGCCCACTGCCCTA |

| Introduction of mutation | |

| FAIM promoter mutation A (forward) | GCATTTTAAAAATCTATTCATAGAGGCTCTTTTATGTAAGGGGTAC |

| FAIM promoter mutation A (reverse) | GTACCCCTTACATAAAAGAGCCTCTATGAATAGATTTTTAAAATGC |

| FAIM promoter mutation B (forward) | ATGTTGCAGATACCGTGCCTGAGGCTTCTGCTTCATTAAATTTTAC |

| FAIM promoter mutation B (reverse) | GTAAAATTTAATGAAGCAGAAGCCTCAGGCACGGTATCTGCAACAT |

| FAIM promoter mutation C (forward) | TTCCCTTTATATAAATGAGGCTGTAGATTCTATCCGAC |

| FAIM promoter mutation C (reverse) | GTCGGATAGAATCTACAGCCTCATTTATATAAAGGGAA |

All sequences are presented in the 5′ to 3′ direction.

Reporter plasmids

The FAIM proximal promoter genomic region (−1631 to +20 and, separately, −598 to +20) was amplified by PCR using LA-Taq and cloned into the pGL4.10 luciferase vector (Promega). Mutant promoter reporter constructs were prepared using LA-Taq and the QuickChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). The insert was verified by sequencing (Genewiz). FAIM promoter-dependent luciferase vectors were cotransfected with pRL-TK (Renilla luciferase) vector using the Nucleofector kit V (Amaxa) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. At 24 h after transfection, luciferase activity in cell lysates was analyzed by the dual-luciferase reporter assay system (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, using a 20/20n single tube luminometer (Turner BioSystems). Relative luciferase activity was calculated as firefly luciferase activity/Renilla luciferase activity. The sequences of the primer sets for cloning are shown in Table I.

Western blotting

Proteins were extracted from B cell pellets with Nonidet P-40 lysis buffer, and equal amounts of protein for each condition were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting, as previously described (12).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

ChIP assay was carried out according to the manufacturer’s (Upstate Biotechnology) protocol, as previously described, with slight modification (13). Briefly, primary splenic B cells (2 × 106) were subjected to chromatin cross-linking in 1% formaldehyde for 2 min at 37°C, and quenched with 125 mM glycine. Cell lysates were sonicated to shear the DNA length to between 200 and 2000 bp; DNA was extracted from a fraction of the lysates for input controls. Precleared lysates were incubated overnight at 4°C with 4 µg of rabbit anti-IRF4 Ab or with normal rabbit IgG. Cross-linking was reversed and input and immunoprecipitated DNA samples were assayed for the FAIM promoter sequence by real-time PCR. The sequences of the primer sets used in the ChIP assays are shown in Table I.

Abs and reagents

CD40L was prepared and used as previously described (14–16). Affinity-purified F(ab′)2 fragments of goat anti-mouse IgM (anti-Ig) were obtained from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories. Monoclonal anti-FcγR Ab 2.4G2, anti-B220-FITC, anti-B220-PE, anti-CD23-PE and anti-CD43-biotin were obtained from BD Pharmingen. PNA-FITC was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Streptavidin-PE was obtained from Biomeda. Monoclonal anti-GL7-Alexa 647 was obtained from eBioscience. Monoclonal anti-B220-PerCP was obtained from BioLegend. Monoclonal anti-phosphotyrosine Ab 4G10 was obtained from Upstate Biotechnology. Affinity-purified anti-FAIM Ab was obtained from rabbits immunized with CYIKAVSSRKRKEGIIHTLI peptide (located near the C-terminal region of FAIM). Rabbit anti-IRF4 Ab was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Anti-tubulin Ab was obtained from Calbiochem. Anti-actin Ab was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich.

Results

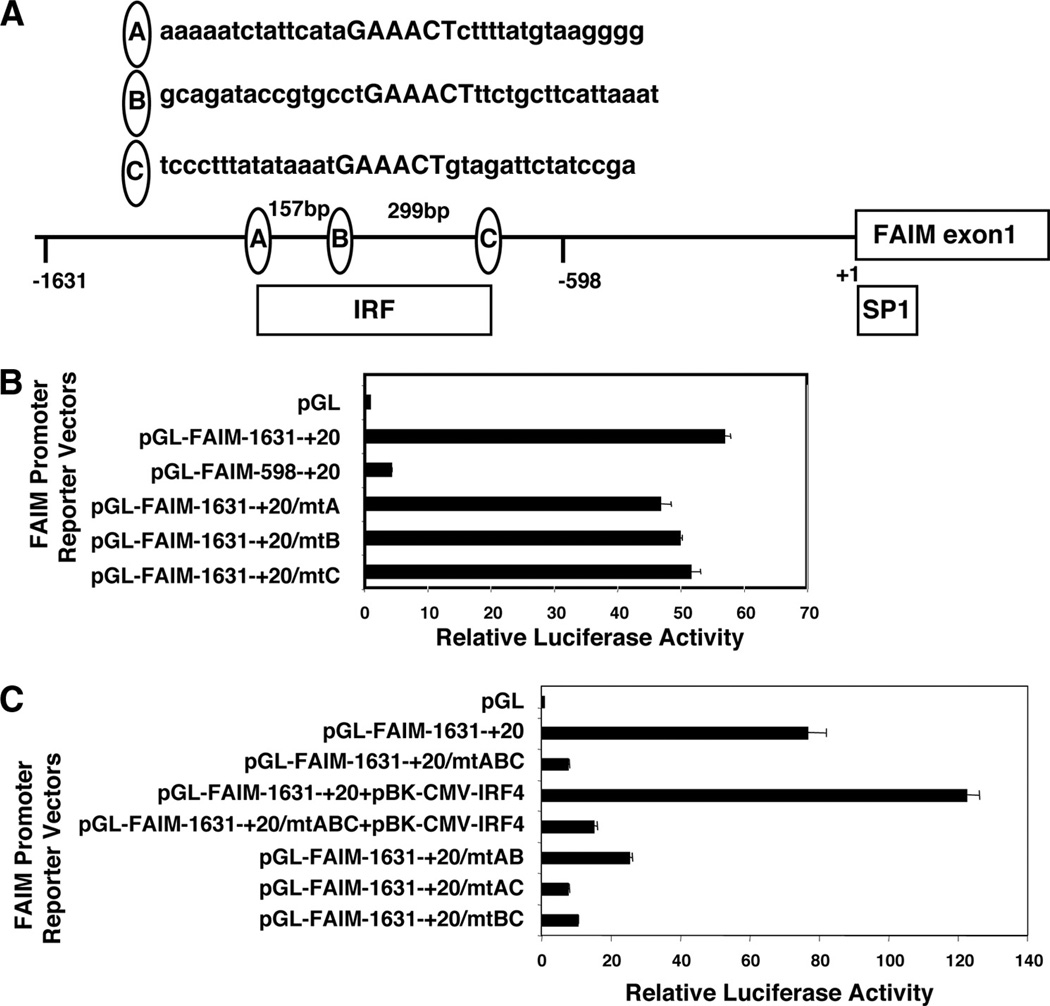

FAIM expression is regulated by IRF consensus sites

To identify the regulatory factors responsible for FAIM expression, we analyzed the putative Faim promoter sequence, upstream from the transcription start site, as described in the National Center for Biotechnology Information database. We found three putative IRF binding consensus motifs as previously defined (GAAAC(T/C) (17), located between −1600 and −600 in relation to the transcription start site (depicted as sites “A”, “B”, and “C”, along with flanking sequences, in Fig. 1A), and one Sp1 binding site located near the transcription start site.

FIGURE 1.

FAIM expression is regulated by IRF consensus sites. A, The locations of three IRF binding sites and one SP1 binding site within sequence 2 kb upstream of the FAIM start site are shown. B, A20 cells were transiently transfected with an empty firefly luciferase construct, or with either native, truncated, or mutant Faim promoter-firefly luciferase reporter constructs, as indicated, along with, in each case, a thymidine kinase promoter-dependent Renilla luciferase expression vector, after which lysates were prepared, firefly luciferase activity was measured in relation to the Renilla luciferase control, and results were reported as multiples of the activity present with empty vector. Mean values for three independent experiments are shown, along with lines corresponding to the SEM. C, A20 cells were transiently transfected with an empty firefly luciferase construct, or with native and mutant Faim promoter-firefly luciferase constructs with or without a CMV-driven IRF4 expression vector, as indicated, along with, in each case, a thymidine kinase promoter-dependent Renilla luciferase expression vector, after which lysates were prepared, firefly luciferase activity was measured in relation to the Renilla luciferase control, and results were reported as multiples of the activity present with empty vector. Mean values for three independent experiments are shown, along with lines corresponding to the SEM.

To determine whether the IRF binding sites, or the Sp1 site, play a role in regulating FAIM expression, we first constructed two Faim promoter firefly luciferase reporter vectors, −1631 to +20 and −598 to +20, and transfected these constructs, and empty vector, into the A20 B cell line. We then evaluated luciferase activity as an indication of Faim promoter function. We found that the promoter sequence −1631/+20 was highly active, promoting a >50-fold increase in luciferase activity in comparison to luciferase activity produced by empty vector alone (Fig. 1B). In contrast, the truncated sequence −598/+20, which lacks the IRF binding sites (but contains the Sp1 site), was relatively inactive, promoting only a 3-fold increase in luciferase activity as compared with that produced by empty vector. These results indicate that the interval between −1631 and −598 (proximal to the Faim transcription start site) contains a strong enhancer region for FAIM expression. We concluded that the three IRF binding sites contained within this sequence represent prime candidates for directing FAIM expression.

To verify the role of the IRF binding sites, we introduced mutations into each motif individually and in combination by changing GAAAC(T/C) to GAggC(T/C) in the Faim −1631/+20 promoter construct, because this mutation abolishes IRF binding (18). These mutant Faim promoter constructs were transfected into A20 cells, after which luciferase activity was determined. We found that mutation of one site at a time, be it site A, B, or C, had little effect on reporter activity driven by the −1631/+20 sequence (Fig. 1B). This suggests that none of the IRF binding sites is, by itself, determinative, and, furthermore, that all three sites need not be intact for normal promoter function. On the other hand, mutation of all three sites produced marked loss of promoter function (Fig. 1C). This indicates that the IRF sites are, in some combination, responsible for the promoter activity of the Faim −1631/+20 construct.

In separate experiments these same Faim promoter constructs were transfected into two additional B cell lines, BRD2 (19) and BAL-17 (20), yielding results that faithfully reproduced our findings with A20 cells in all key aspects (the −1631/+20 construct was highly active, the −598/+20 construct was little active, the ABC mutant lost virtually all activity, and mutation of either A, or B, or C sites had little or no effect; data not shown). Thus, our findings with these key Faim promoter constructs are not limited to A20 cells.

Next, we introduced mutations into the three IRF binding sites two at a time and evaluated promoter activity of the doubly mutated −1631/+20 promoter sequences in A20 cells. We found that mutation of two sites markedly reduced resultant luciferase activity; moreover, this was true regardless of which two sites were mutated (Fig. 1C). Thus, mutation of the AB, the AC, or the BC sites substantially blocked promoter function in each case, with mutation of the AC and BC sites having the largest effect. Thus, these results strongly suggest that two (of the three) IRF sites act together to drive full activation of the FAIM promoter.

Among the nine-member IRF family, IRF4 is most likely to play a role in activated B cells (21, 22), for which reason we introduced a CMV-driven IRF4 expression vector together with the aforementioned luciferase vectors into A20 cells. We reasoned that introduction of promoter-reporter plasmids into A20 cells might produce an excess of binding sites over available, endogenous IRF4, in which case introduction of IRF4, if it plays a role, would act to enhance reporter gene activity. In fact, cotransfection of CMV-driven IRF4 increased luciferase activity produced by the native Faim −1631/+20 promoter by 1.5- to 2-fold, providing further evidence of a role for the IRF4 binding sites within the −1631/+20 sequence. Conversely, as might be expected, coexpression of IRF4 had little effect on the Faim promoter construct in which all three IRF binding sites had been mutated. These data suggest that IRF4 regulates Faim gene transcription in a positive manner.

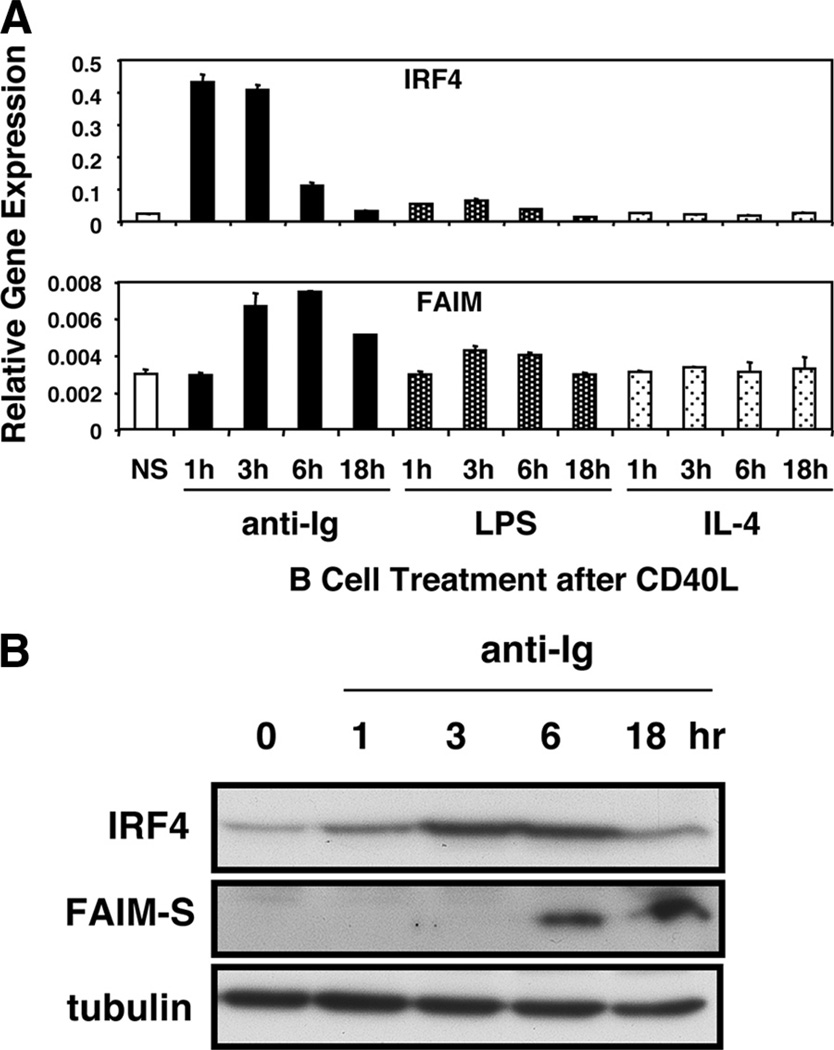

IRF4 expression precedes FAIM expression in stimulated B cells

We previously showed that FAIM expression is up-regulated by anti-Ig stimulation of CD40L-pretreated murine splenic B cells (1). To further evaluate the correlation between IRF4 and FAIM, we examined the time course of Irf4 and Faim mRNA and protein expression in stimulated primary B cells. As expected, we found that Faim gene expression was induced by anti-Ig stimulation of CD40L-pretreated cells; Faim mRNA was increased over baseline within 3 h and peaked at 6 h, declining somewhat by 18 h. We found that Irf4 gene expression was induced and peaked earlier, preceding induction of Faim; Irf4 mRNA was markedly increased over baseline at 1 h, which was also the time of peak induction, and had declined to background levels by 18 h (Fig. 2A). Similar results were obtained when we monitored IRF4 and FAIM protein expression by Western blotting. As with mRNA expression, we found that IRF4 protein was induced hours before FAIM protein when CD40L-treated B cells were stimulated with anti-Ig (Fig. 2B). Thus, the time course of stimulated IRF4 and FAIM expression in primary B cells is consistent with a model in which IRF4 plays a key role in directing FAIM expression.

FIGURE 2.

Stimulated FAIM expression is preceded by induction of IRF4 expression in primary B cells. A, Primary B cells were stimulated by CD40L for 48 h alone (NS), or were stimulated by CD40L for 48 h during which time either anti-Ig, LPS, or IL-4 was added for the final number of hours indicated. From these cells, RNA was prepared, reverse transcribed, and evaluated for Faim and for Irf4 gene expression by real-time PCR. Expression levels were normalized to β2-microglobulin. Mean values for two independent experiments are shown, along with lines corresponding to the SEM. B, Primary B cells were stimulated by CD40L for 48 h alone (0 h), or were stimulated by CD40L for 48 h during which time anti-Ig was added for the final number of hours indicated. From these cells, lysates were prepared and evaluated for expression of FAIM-S and IRF4 by Western blotting. Blots were stripped and reprobed for tubulin content as a loading control. One of two comparable experiments is shown.

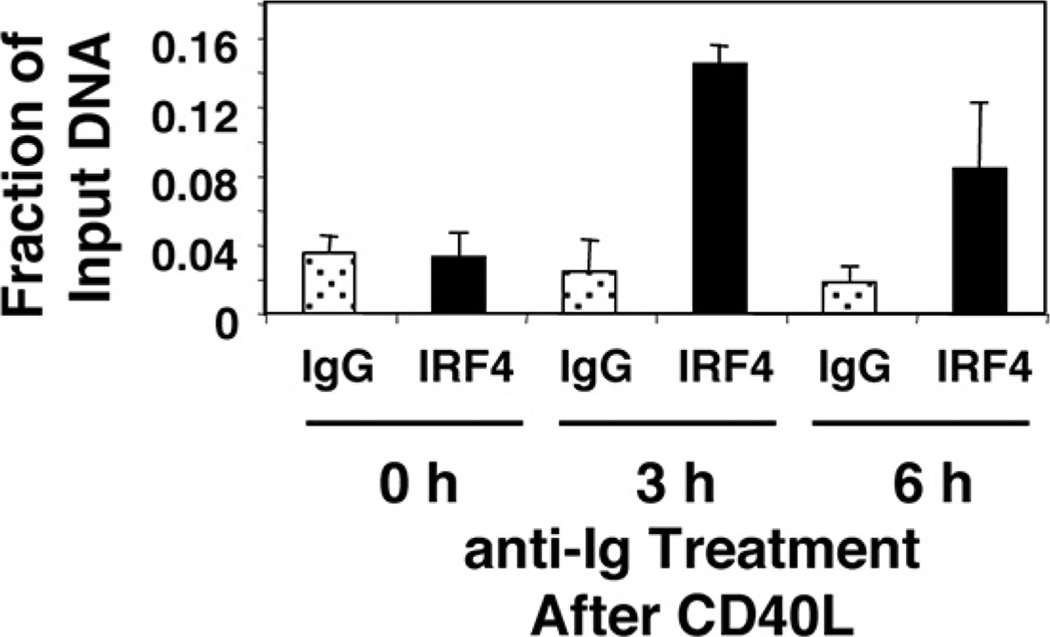

IRF4 binds to the FAIM promoter in vivo

To directly test the role of IRF4 in regulating the Faim promoter, we carried out ChIP in primary (murine splenic) B cells pretreated with CD40L and then stimulated with anti-Ig to induce FAIM expression. With separate primers we evaluated the Igλ 3′ enhancer region as a positive control (23). As expected, we found that IRF4 bound to the Igλ 3′ enhancer region (data not shown). Importantly, we found that IRF4 bound to sites within the Faim promoter after, but not before, anti-Ig was added to CD40L-treated B cells (Fig. 3), the same conditions required for induction of FAIM expression. Thus, IRF4 binding to the Faim promoter is induced specifically by conditions that induce FAIM expression in primary B cells, indicating that Faim is an IRF4 target gene and further implicating IRF4 in the regulation of FAIM expression.

FIGURE 3.

IRF4 binds the Faim promoter in stimulated primary B cells. Primary B cells were stimulated by CD40L for 48 h alone (0 h) or were stimulated by CD40L for 48 h during which time anti-Ig was added for the final number of hours indicated and ChIP assay was carried out. Cells were lysed and DNA was sheared by sonication, after which chromatin was immunoprecipitated with anti-IRF4 Ab or control IgG, and Faim promoter sequence was amplified by real-time PCR. Results are expressed as the degree of amplification relative to input DNA. Mean values for two independent experiments are shown, along with lines corresponding to the SEM.

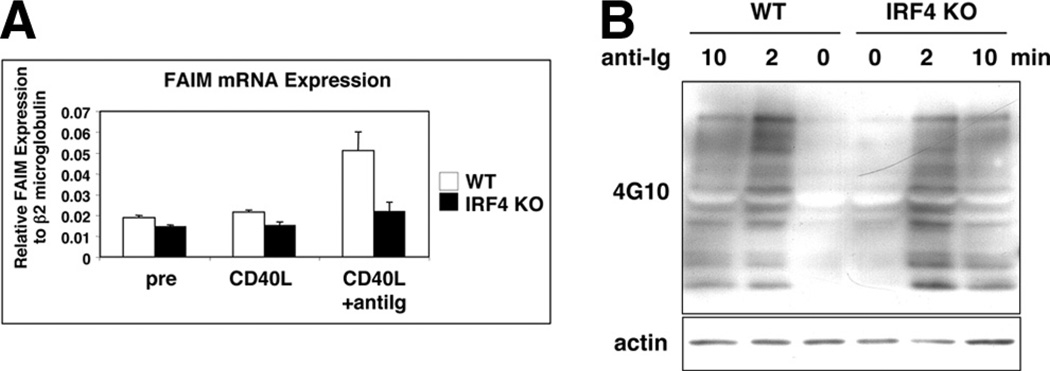

Up-regulation of Faim expression requires IRF4

To further test the role of IRF4 in regulating the Faim promoter, we evaluated stimulated Faim mRNA expression in follicular B cells sort-purified from the spleens of IRF4-null mice and litter-mate control mice. B cells were cultured with CD40L for 48 h alone or were cultured with CD40L for 48 h, during which time anti-Ig was added for the last 6 h before the end of the 48-h culture period. We then determined Faim gene expression in these cells by real-time PCR. As expected, we observed that FAIM mRNA expression was enhanced (by 2.4-fold) in CD40L- and anti-Ig-stimulated wild-type (WT) B cells (Fig. 4A). In contrast, enhancement of FAIM expression by anti-Ig stimulation was substantially impaired in IRF4-null B cells amounting to less than a third that of WT B cells (p < 0.01, n = 3) (Fig. 4A). To rule out the possibility that BCR signaling is blocked in IRF4-null B cells, we examined general protein tyrosine phosphorylation. We found no difference in BCR-triggered inducible phosphorylation between IRF4-null B cells and WT B cells (Fig. 4B). Thus, inducible expression of Faim largely fails in the absence of IRF4, indicating that IRF4 is required for normal up-regulation of Faim gene expression in primary B cells.

FIGURE 4.

IRF4 plays a nonredundant role in up-regulating FAIM expression. Follicular B cells from IRF4-null mice and from littermate control mice were sort-purified as described in Materials and Methods and then harvested before stimulation, or were stimulated and then harvested. Follicular B cells were >95% pure upon postsort reanalysis. A, B cells were stimulated by CD40L for 48 h alone (CD40L) or they were stimulated by CD40L for 48 h, during which time anti-Ig was added for the final 6 h of culture. RNA was prepared, reverse transcribed, and evaluated for Faim gene expression by real-time PCR. Faim expression was normalized to expression of β2-microglobulin. Mean values for three independent experiments are shown, along with lines corresponding to the SEM. B, Sort-purified B cells from IRF4-null and from littermate control mice were unstimulated or were stimulated by anti-Ig for 2 or 10 min. B cell lysates were prepared and evaluated for expression of phosphorylated proteins by Western blotting with 4G10 anti-phosphotyrosine Ab. Blots were reprobed for expression of actin as a loading control.

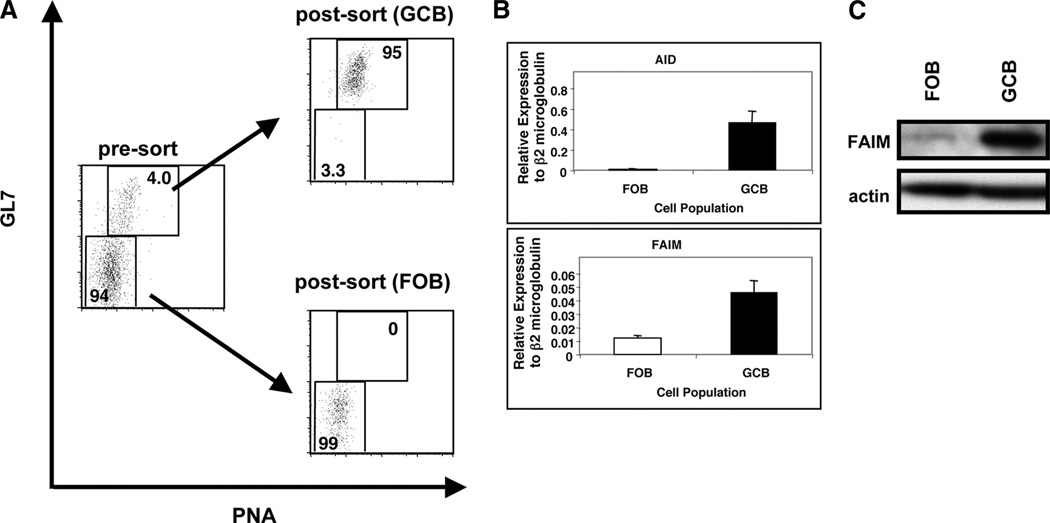

FAIM is expressed in germinal center B cells

It has been reported that FAIM mRNA expression is elevated in human germinal center B cells (24). To examine whether FAIM is expressed in mouse germinal center B cells (GCB), we sort-purified germinal center (B220+, PNAhigh, GL7high) and follicular B cells (FOB; B220+, PNAlow, GL7low) from mouse splenocytes immunized with TNP-KLH in alum. Isolated GCB and FOB were >94% and >99% pure, respectively (Fig. 5A). We then analyzed GCB for Aid and Faim gene expression. We found that Aid, a marker of GCB, was highly expressed in GCB but little expressed in FOB, confirming the efficiency of sort purification. Using the same cDNA samples, we found that Faim expression was up-regulated in GCB (by ~4–5-fold) as compared with FOB (p < 0.01, n = 5) (Fig. 5B). We further monitored FAIM protein expression in these populations by Western blotting and found that FAIM expression was increased in GCB as compared with FOB at the protein level (Fig. 5C). These data indicate that FAIM mRNA and protein expression are preferentially up-regulated in mouse GCB.

FIGURE 5.

FAIM is elevated in GCB. A, Mice were immunized with TNP-KLH in alum. At 10–14 days after immunization, GCB and FOB were sort-purified as described in Materials and Methods. FOB were >99% pure and GCB were >94% pure upon postsort reanalysis. B, From sorted GCB and FOB, RNA was prepared, reverse transcribed, and evaluated for expression of Aid, and of Faim by real-time PCR. Expression levels were normalized to β2-microglobulin. Mean values for five independent experiments are shown, along with lines corresponding to the SEM. C, From sorted GCB and FOB, lysates were prepared and evaluated for expression of FAIM by Western blotting. Blots were stripped and reprobed for actin content as a loading control. One of two comparable experiments is shown.

Discussion

FAIM affects B cells in two important ways: (1) FAIM opposes Fas-mediated apoptosis in B cells, an activity emphasized by the reported Fas sensitivity of FAIM-null immune cells, which in turn demonstrates the nonredundant nature of FAIM function; and (2) FAIM enhances CD40 signaling in B cells, augmenting NF-κB activation, BCL-6 loss, and IRF4 expression, as well as boosting the plasma cell population (1, 6, 7). These immune system effects, along with reported activities in neuronal cells and other cell types, have heightened interest in elucidating how FAIM expression is regulated in vivo. To address this important issue we examined the Faim upstream region computationally and experimentally. We concluded that Faim promoter activity is regulated by IRF4 because: (1) the Faim promoter contains 3 IRF binding sites; (2) Faim promoter activity is lost following deletion or mutation of all three IRF binding sites (Fig. 1); (3) Faim promoter activity is enhanced by concurrent expression of IRF4 (Fig. 1); (4) IRF4 expression precedes FAIM expression in primary B cells stimulated ex vivo (Fig. 2); (5) IRF4 binds directly to the Faim promoter in primary B cells in vivo (Fig. 3); and (6) absence of IRF4 impairs induction of FAIM expression in primary B cells ex vivo (Fig. 4). Because FAIM enhances CD40-induced IRF4 expression in B cells, our results in this study suggest that induction of FAIM initiates a positive reinforcing (i.e., feed-forward) system in which IRF4 expression is both enhanced by FAIM and promotes FAIM expression. It may be speculated that once induced, FAIM can then perpetuate itself through enhancement of IRF4 expression, until such point as, through mechanisms unknown at the present time, FAIM expression declines, CD40 signaling ceases, or B cells become fully differentiated. The FAIM-influenced level of IRF4 would then be expected to determine B cell fate, inasmuch as the level of IRF4 has been shown to determine the level of plasma cell differentiation (23), which we have demonstrated elsewhere is enhanced by FAIM (7).

All three IRF binding sites in the Faim promoter appear to be active. A similar situation exists in the IL-4 promoter, in that all of the three tandem IRF1 and IRF2 binding sites are functional for IL-4 gene repression induced by IFN-γ in T cells (25). In the Faim promoter, however, individual IRF sites alone produce little promoter activity, whereas two promoter sites together generate virtually full activity and there is little preference for one combination over another; that is, any two will do. The mechanism for this remains unclear, particularly in view of the varied intersite distances involved with various binding site combinations, but presumably some interaction is required.

It would appear that IRF4 is not the sole determinant of FAIM expression because FAIM is poorly stimulated by CD40L alone, which induces IRF4 expression, but is instead strongly stimulated by the combined action of CD40L and anti-Ig, and because FAIM is expressed in germinal center B cells (Fig. 5) but not in CD138+ plasma cells (data not shown), which abundantly express IRF4 (26). In addition, it is important to note that non-IRF4 factors could be involved in regulating FAIM expression. For example, the potential participation of long-range elements beyond −1631 has not been ruled out. Furthermore, elements within −1631 to +20 could play a role, particularly in terms of the constitutive level of FAIM that was not affected by loss of IRF4. In preliminary experiments, we carried out EMSA binding assays using as probes seven different 240-bp sequences that spanned the region −1631 to +49, and we found evidence for binding with at least one probe (−671/−423), although it is impossible at this stage, without knowledge of a target motif, to rule out nonspecific binding. However, if this binding does represent a specific nucleoprotein complex, the factor involved most likely plays a role only in constitutive IRF4 expression inasmuch as binding did not change with B cell stimulation for FAIM induction (data not shown).

Like FAIM, activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) is expressed in GCB (27) but not in plasma cells. AID is responsible for somatic hypermutation within germinal centers, resulting in the generation of Ig molecules that express a spectrum of binding affinities for specific Ag (28). The phenomenon of affinity maturation depends on positive selection of B cells bearing high-affinity Ag-binding Ig for further development and differentiation and on negative selection of outcompeted B cells bearing low-affinity Ig. Positive B cell selection within germinal centers depends on signals generated by BCR and CD40 engagement (29), signals that together lead to induction of FAIM, which is shown here and elsewhere to be up-regulated in GCB. FAIM in turn appears to foster the continued development of Ag-binding B cells in two ways, both of which may depend on the ability of FAIM to enhance CD40 signaling for NF-κB (7). On the one hand, FAIM enhances up-regulation of FLIP expression (data not shown and Ref. 6)), which opposes death receptor-mediated apoptosis (30). On the other hand, FAIM enhances down-regulation of BCL-6 and up-regulation of IRF4, which propel B cell differentiation (7). Our new finding that FAIM expression is regulated by IRF4, levels of which are enhanced by FAIM, suggests a mechanism whereby, once induced, FAIM promotes its own expression, resulting in a stable push in favor of continued GCB development and differentiation.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to our colleagues for helpful discussions and technical assistance throughout the course of this study. We particularly thank Dr. Ulf Klein for providing IRF4-null mice, for critical reading of the manuscript, and for valuable suggestions.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by U.S. Public Health Service Grants AI040181 and AI083509.

Abbreviations used in this paper: AID, activation-induced cytidine deaminase; BCL-6, B cell lymphoma-6; ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; FAIM, Fas apoptosis inhibitory molecule; FOB, follicular B cell; GCB, germinal center B cell; IRF, IFN regulatory factor; PNA, peanut agglutinin; TNP-KLH, 2,4,6-trinitrophenyl-keyhole limpet hemocyanin; WT, wild type.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Schneider TJ, Fischer GM, Donohoe TJ, Colarusso TP, Rothstein TL. A novel gene coding for a Fas apoptosis inhibitory molecule (FAIM) isolated from inducibly Fas-resistant B lymphocytes. J. Exp. Med. 1999;189:949–956. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.6.949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhong X, Schneider TJ, Cabral DS, Donohoe TJ, Rothstein TL. An alternatively spliced long form of Fas apoptosis inhibitory molecule (FAIM) with tissue-specific expression in the brain. Mol. Immunol. 2001;38:65–72. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(01)00035-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hemond M, Rothstein TL, Wagner G. Fas apoptosis inhibitory molecule contains a novel β-sandwich in contact with a partially ordered domain. J. Mol. Biol. 2009;386:1024–1037. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rothstein TL, Wang JK, Panka DJ, Foote LC, Wang Z, Stanger B, Cui H, Ju ST, Marshak-Rothstein A. Protection against Fas-dependent Th1-mediated apoptosis by antigen receptor engagement in B cells. Nature. 1995;374:163–165. doi: 10.1038/374163a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foote LC, Schneider TJ, Fischer GM, Wang JK, Rasmussen B, Campbell KA, Lynch DH, Ju ST, Marshak-Rothstein A, Rothstein TL. Intracellular signaling for inducible antigen receptor-mediated Fas resistance in B cells. J. Immunol. 1996;157:1878–1885. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huo J, Xu S, Guo K, Zeng Q, Lam KP. Genetic deletion of faim reveals its role in modulating c-FLIP expression during CD95-mediated apoptosis of lymphocytes and hepatocytes. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16:1062–1070. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaku H, Rothstein TL. FAIM enhances CD40 signaling in B cells and augments the plasma cell compartment. J. Immunol. 2009;183:1667–1674. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sole C, Dolcet X, Segura MF, Gutierrez H, Diaz-Meco MT, Gozzelino R, Sanchis D, Bayascas JR, Gallego C, Moscat J et al. The death receptor antagonist FAIM promotes neurite outgrowth by a mechanism that depends on ERK and NF-κB signaling. J. Cell Biol. 2004;167:479–492. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200403093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klein U, Casola S, Cattoretti G, Shen Q, Lia M, Mo T, Ludwig T, Rajewsky K, Dalla-Favera R. Transcription factor IRF4 controls plasma cell differentiation and class-switch recombination. Nat. Immunol. 2006;7:773–782. doi: 10.1038/ni1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mittrucker HW, Matsuyama T, Grossman A, Kundig TM, Potter J, Shahinian A, Wakeham A, Patterson B, Ohashi PS, Mak TW. Requirement for the transcription factor LSIRF/IRF4 for mature B and T lymphocyte function. Science. 1997;275:540–543. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5299.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frances R, Tumang JR, Rothstein TL. Cutting edge: B-1 cells are deficient in Lck: defective B cell receptor signal transduction in B-1 cells occurs in the absence of elevated Lck expression. J. Immunol. 2005;175:27–31. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mizuno T, Rothstein TL. B cell receptor (BCR) cross-talk: CD40 engagement creates an alternate pathway for BCR signaling that activates IκB kinase/IκBα/NF-κB without the need for PI3K and phospholipase Cγ. J. Immunol. 2005;174:6062–6070. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.6062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Repetny KJ, Zhong X, Holodick NE, Rothstein TL, Hansen U. Binding of LBP-1a to specific immunoglobulin switch regions in vivo correlates with specific repression of class switch recombination. Eur. J. Immunol. 2009;39:1387–1394. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lane P, Brocker T, Hubele S, Padovan E, Lanzavecchia A, McConnell F. Soluble CD40 ligand can replace the normal T cell-derived CD40 ligand signal to B cells in T cell-dependent activation. J. Exp. Med. 1993;177:1209–1213. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.4.1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Francis DA, Karras JG, Ke XY, Sen R, Rothstein TL. Induction of the transcription factors NF-κB, AP-1 and NF-AT during B cell stimulation through the CD40 receptor. Int. Immunol. 1995;7:151–161. doi: 10.1093/intimm/7.2.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mizuno T, Rothstein TL. Cutting edge: CD40 engagement eliminates the need for Bruton’s tyrosine kinase in B cell receptor signaling for NF-κB. J. Immunol. 2003;170:2806–2810. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.6.2806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuo TC, Calame KL. B lymphocyte-induced maturation protein (Blimp)-1, IFN regulatory factor (IRF)-1, and IRF-2 can bind to the same regulatory sites. J. Immunol. 2004;173:5556–5563. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.9.5556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gongora C, Degols G, Espert L, Hua TD, Mechti N. A unique ISRE, in the TATA-less human Isg20 promoter, confers IRF-1-mediated responsiveness to both interferon type I and type II. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:2333–2341. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.12.2333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greenwald RJ, Tumang JR, Sinha A, Currier N, Cardiff RD, Rothstein TL, Faller DV, Denis GV. Eµ-BRD2 transgenic mice develop B-cell lymphoma and leukemia. Blood. 2004;103:1475–1484. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-06-2116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chiles TC, Rothstein TL. Surface Ig receptor-induced nuclear AP-1-dependent gene expression in B lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 1992;149:825–831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tamura T, Yanai H, Savitsky D, Taniguchi T. The IRF family transcription factors in immunity and oncogenesis. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2008;26:535–584. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Honda K, Taniguchi T. IRFs: master regulators of signalling by Toll-like receptors and cytosolic pattern-recognition receptors. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2006;6:644–658. doi: 10.1038/nri1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sciammas R, Shaffer AL, Schatz JH, Zhao H, Staudt LM, Singh H. Graded expression of interferon regulatory factor-4 coordinates isotype switching with plasma cell differentiation. Immunity. 2006;25:225–236. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shen Y, Iqbal J, Xiao L, Lynch RC, Rosenwald A, Staudt LM, Sherman S, Dybkaer K, Zhou G, Eudy JD. Distinct gene expression profiles in different B-cell compartments in human peripheral lymphoid organs. BMC Immunol. 2004;5:20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-5-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elser B, Lohoff M, Kock S, Giaisi M, Kirchhoff S, Krammer PH, Li-Weber M. IFN-γ represses IL-4 expression via IRF-1 and IRF-2. Immunity. 2002;17:703–712. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00471-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu R. Interferon regulatory factor 4 and 8 in B-cell development. Trends Immunol. 2008;29:487–492. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muramatsu M, Sankaranand VS, Anant S, Sugai M, Kinoshita K, Davidson NO, Honjo T. Specific expression of activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), a novel member of the RNA-editing deaminase family in germinal center B cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:18470–18476. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.26.18470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muramatsu M, Kinoshita K, Fagarasan S, Yamada S, Shinkai Y, Honjo T. Class switch recombination and hypermutation require activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), a potential RNA editing enzyme. Cell. 2000;102:553–563. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strasser A, Jost PJ, Nagata S. The many roles of FAS receptor signaling in the immune system. Immunity. 2009;30:180–192. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hennino A, Berard M, Krammer PH, Defrance T. FLICE-inhibitory protein is a key regulator of germinal center B cell apoptosis. J. Exp. Med. 2001;193:447–458. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.4.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]