Abstract

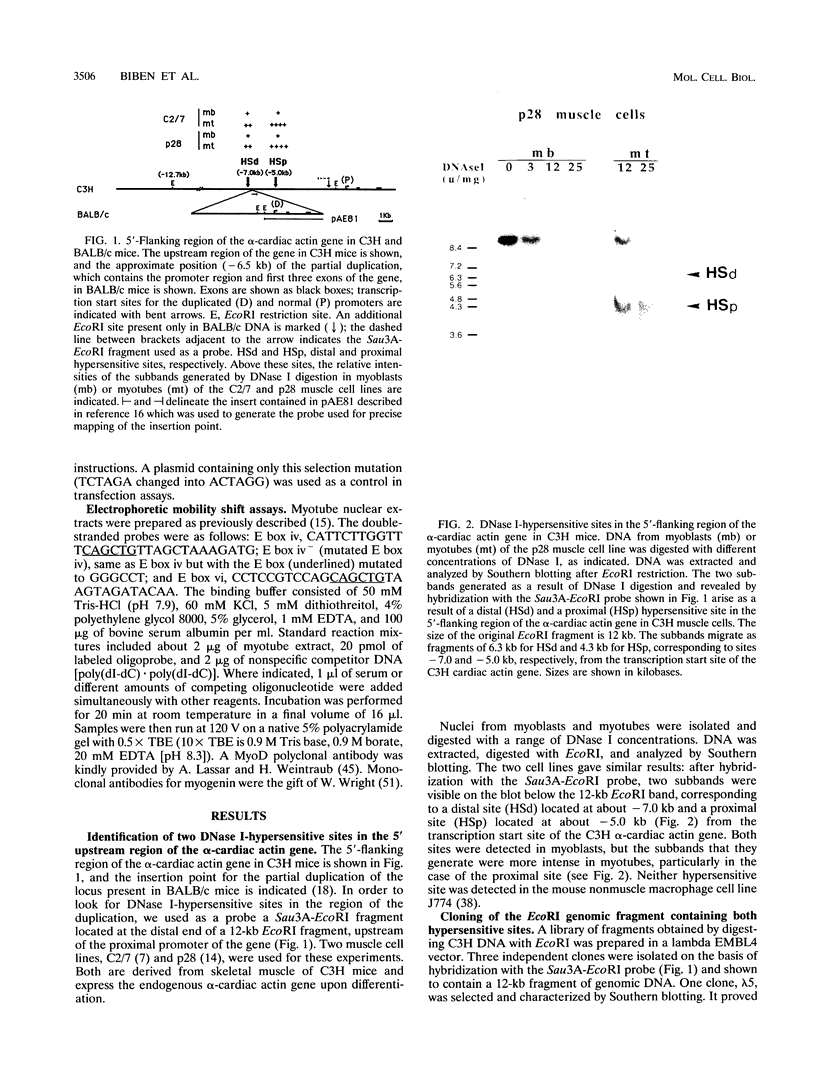

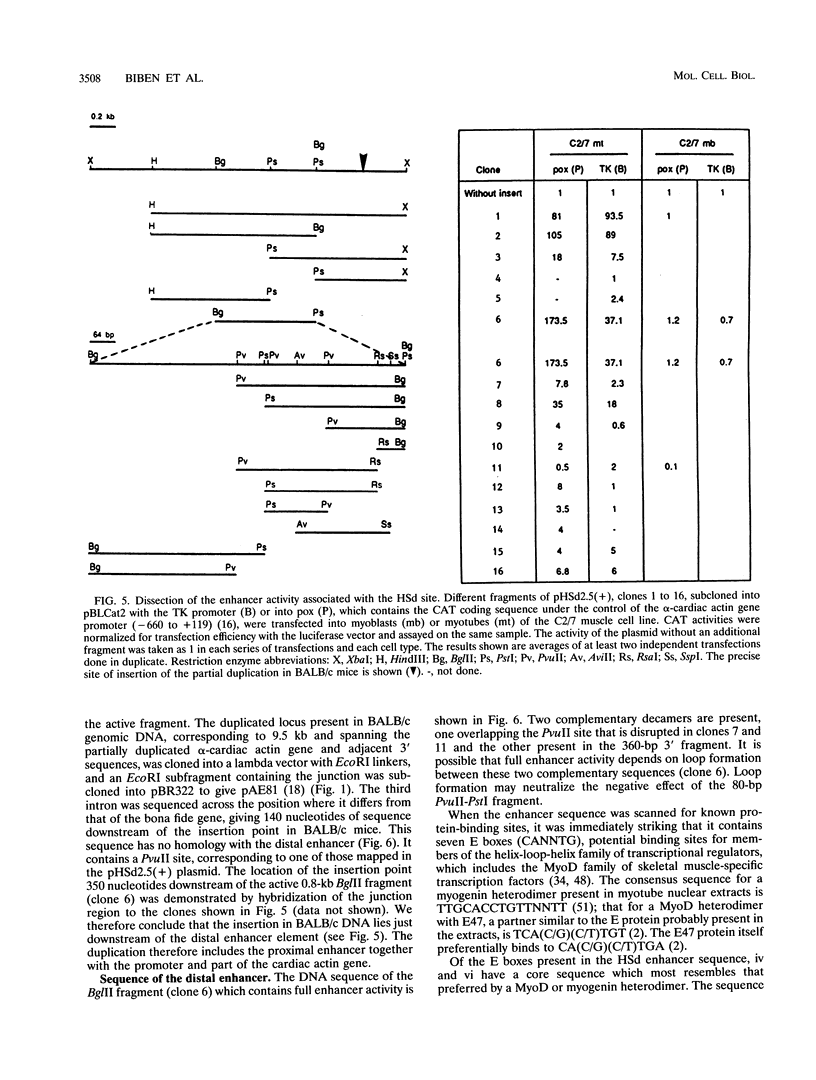

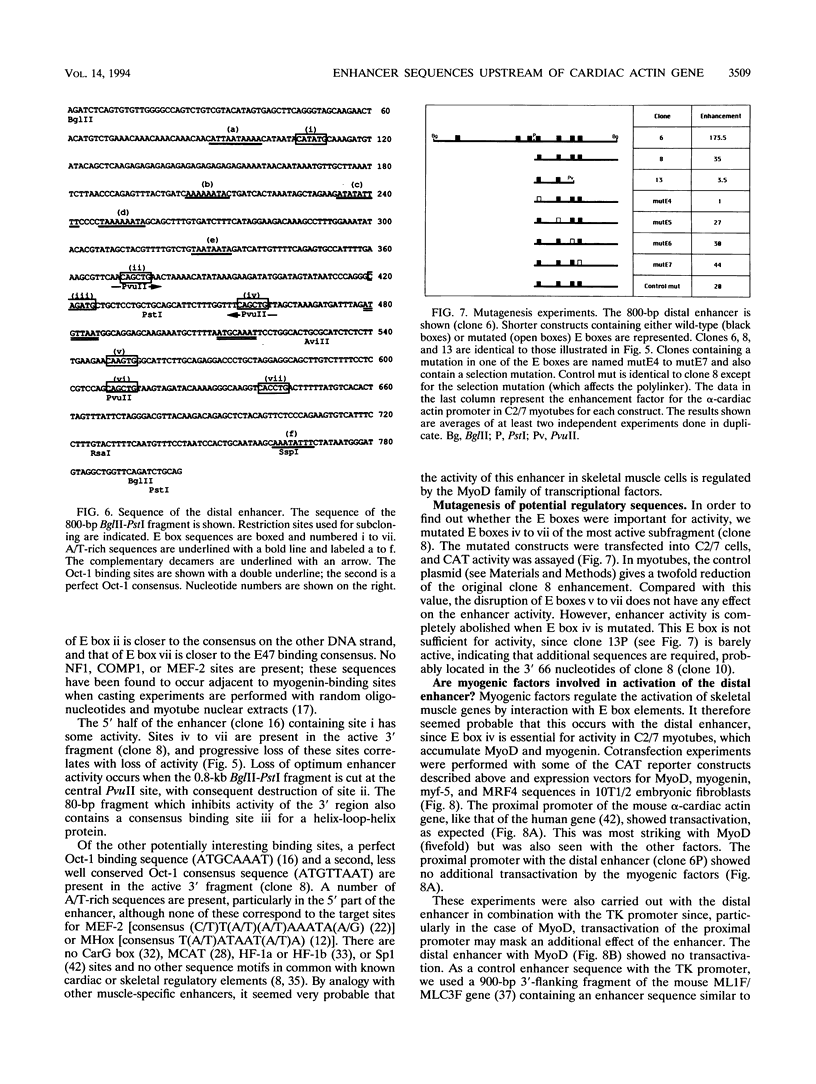

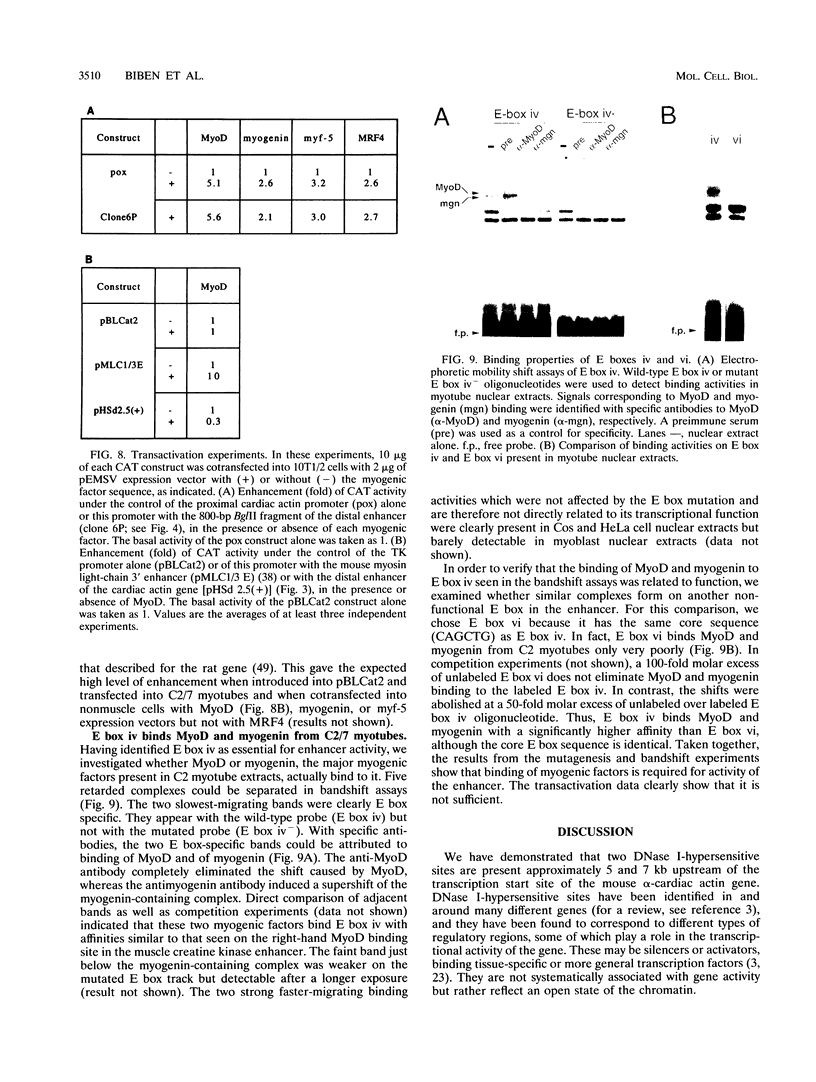

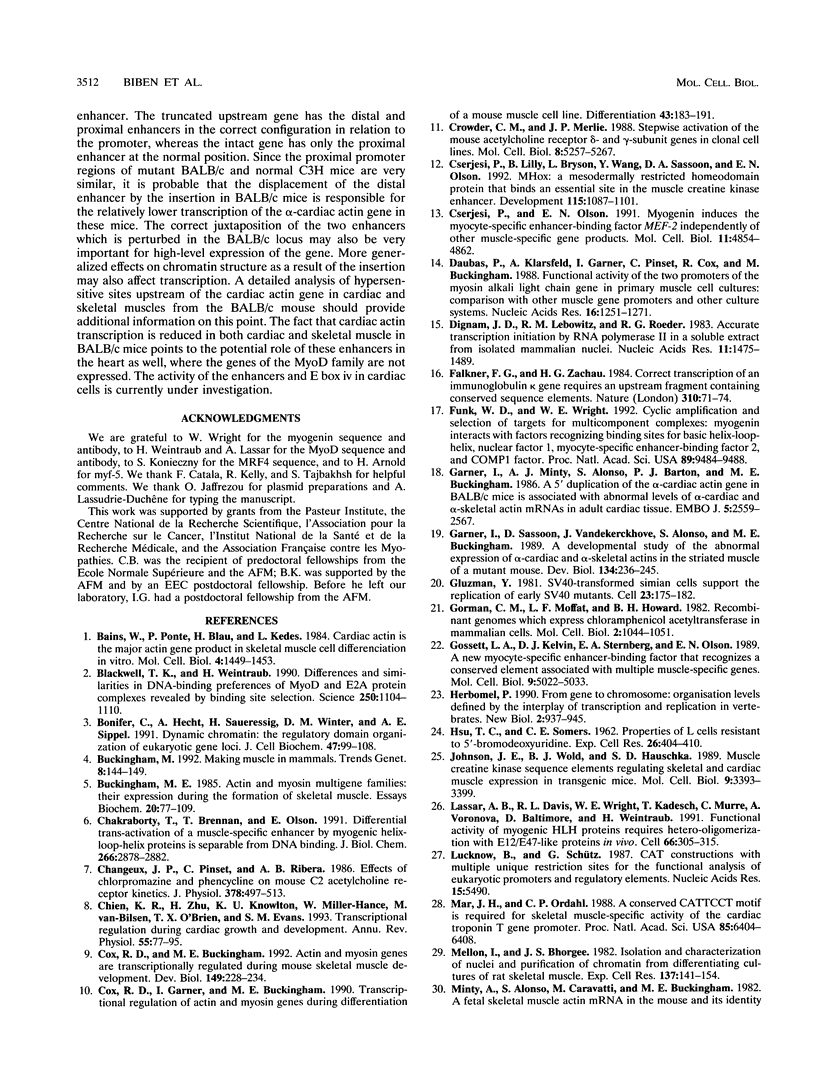

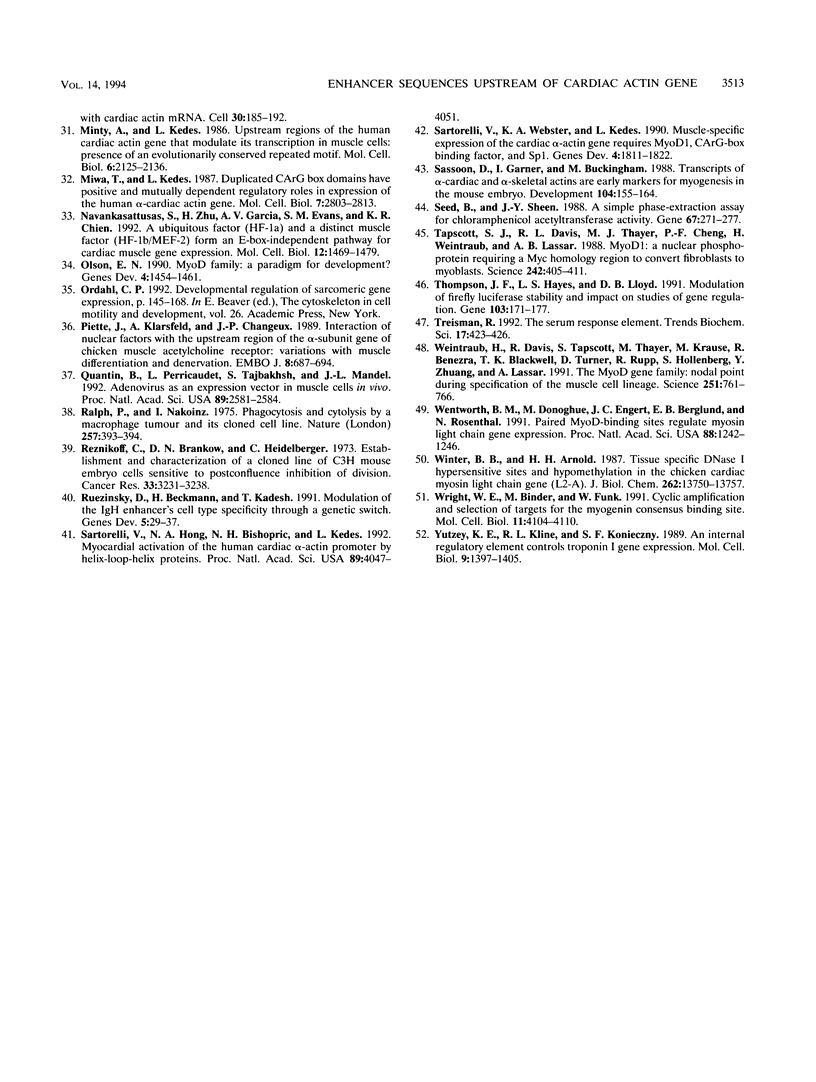

A DNase I-hypersensitive site analysis of the 5'-flanking region of the mouse alpha-cardiac actin gene with muscle cell lines derived from C3H mice shows the presence of two such sites, at about -5 and -7 kb. When tested for activity in cultured cells with homologous and heterologous promoters, both sequences act as muscle-specific enhancers. Transcription from the proximal promoter of the alpha-cardiac actin gene is increased 100-fold with either enhancer. The activity of the distal enhancer in C2/7 myotubes is confined to an 800-bp fragment, which contains multiple E boxes. In transfection assays, this sequence does not give detectable transactivation by any of the myogenic factors even though one of the E boxes is functionally important. Bandshift assays showed that MyoD and myogenin can bind to this E box. However, additional sequences are also required for activity. We conclude that in the case of this muscle enhancer, myogenic factors alone are not sufficient to activate transcription either directly via an E box or indirectly through activation of genes encoding other muscle factors. In BALB/c mice, in which cardiac actin mRNA levels are 8- to 10-fold lower, the alpha-cardiac actin locus is perturbed by a 9.5-kb insertion (I. Garner, A. J. Minty, S. Alonso, P. J. Barton, and M. E. Buckingham, EMBO J. 5:2559-2567, 1986). This is located at -6.5 kb, between the two enhancers. The insertion therefore distances the distal enhancer from the promoter and from the proximal enhancer of the bona fide cardiac actin gene, probably thus perturbing transcriptional activity.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bains W., Ponte P., Blau H., Kedes L. Cardiac actin is the major actin gene product in skeletal muscle cell differentiation in vitro. Mol Cell Biol. 1984 Aug;4(8):1449–1453. doi: 10.1128/mcb.4.8.1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell T. K., Weintraub H. Differences and similarities in DNA-binding preferences of MyoD and E2A protein complexes revealed by binding site selection. Science. 1990 Nov 23;250(4984):1104–1110. doi: 10.1126/science.2174572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonifer C., Hecht A., Saueressig H., Winter D. M., Sippel A. E. Dynamic chromatin: the regulatory domain organization of eukaryotic gene loci. J Cell Biochem. 1991 Oct;47(2):99–108. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240470203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckingham M. E. Actin and myosin multigene families: their expression during the formation of skeletal muscle. Essays Biochem. 1985;20:77–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckingham M. Making muscle in mammals. Trends Genet. 1992 Apr;8(4):144–148. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(92)90373-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty T., Brennan T., Olson E. Differential trans-activation of a muscle-specific enhancer by myogenic helix-loop-helix proteins is separable from DNA binding. J Biol Chem. 1991 Feb 15;266(5):2878–2882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Changeux J. P., Pinset C., Ribera A. B. Effects of chlorpromazine and phencyclidine on mouse C2 acetylcholine receptor kinetics. J Physiol. 1986 Sep;378:497–513. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp016232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien K. R., Zhu H., Knowlton K. U., Miller-Hance W., van-Bilsen M., O'Brien T. X., Evans S. M. Transcriptional regulation during cardiac growth and development. Annu Rev Physiol. 1993;55:77–95. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.55.030193.000453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox R. D., Buckingham M. E. Actin and myosin genes are transcriptionally regulated during mouse skeletal muscle development. Dev Biol. 1992 Jan;149(1):228–234. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(92)90279-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox R. D., Garner I., Buckingham M. E. Transcriptional regulation of actin and myosin genes during differentiation of a mouse muscle cell line. Differentiation. 1990 Jun;43(3):183–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1990.tb00445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowder C. M., Merlie J. P. Stepwise activation of the mouse acetylcholine receptor delta- and gamma-subunit genes in clonal cell lines. Mol Cell Biol. 1988 Dec;8(12):5257–5267. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.12.5257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cserjesi P., Lilly B., Bryson L., Wang Y., Sassoon D. A., Olson E. N. MHox: a mesodermally restricted homeodomain protein that binds an essential site in the muscle creatine kinase enhancer. Development. 1992 Aug;115(4):1087–1101. doi: 10.1242/dev.115.4.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cserjesi P., Olson E. N. Myogenin induces the myocyte-specific enhancer binding factor MEF-2 independently of other muscle-specific gene products. Mol Cell Biol. 1991 Oct;11(10):4854–4862. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.10.4854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daubas P., Klarsfeld A., Garner I., Pinset C., Cox R., Buckingham M. Functional activity of the two promoters of the myosin alkali light chain gene in primary muscle cell cultures: comparison with other muscle gene promoters and other culture systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988 Feb 25;16(4):1251–1271. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.4.1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dignam J. D., Lebovitz R. M., Roeder R. G. Accurate transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II in a soluble extract from isolated mammalian nuclei. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983 Mar 11;11(5):1475–1489. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.5.1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkner F. G., Zachau H. G. Correct transcription of an immunoglobulin kappa gene requires an upstream fragment containing conserved sequence elements. Nature. 1984 Jul 5;310(5972):71–74. doi: 10.1038/310071a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk W. D., Wright W. E. Cyclic amplification and selection of targets for multicomponent complexes: myogenin interacts with factors recognizing binding sites for basic helix-loop-helix, nuclear factor 1, myocyte-specific enhancer-binding factor 2, and COMP1 factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992 Oct 15;89(20):9484–9488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.20.9484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner I., Minty A. J., Alonso S., Barton P. J., Buckingham M. E. A 5' duplication of the alpha-cardiac actin gene in BALB/c mice is associated with abnormal levels of alpha-cardiac and alpha-skeletal actin mRNAs in adult cardiac tissue. EMBO J. 1986 Oct;5(10):2559–2567. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04535.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner I., Sassoon D., Vandekerckhove J., Alonso S., Buckingham M. E. A developmental study of the abnormal expression of alpha-cardiac and alpha-skeletal actins in the striated muscle of a mutant mouse. Dev Biol. 1989 Jul;134(1):236–245. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(89)90093-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gluzman Y. SV40-transformed simian cells support the replication of early SV40 mutants. Cell. 1981 Jan;23(1):175–182. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90282-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman C. M., Moffat L. F., Howard B. H. Recombinant genomes which express chloramphenicol acetyltransferase in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1982 Sep;2(9):1044–1051. doi: 10.1128/mcb.2.9.1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gossett L. A., Kelvin D. J., Sternberg E. A., Olson E. N. A new myocyte-specific enhancer-binding factor that recognizes a conserved element associated with multiple muscle-specific genes. Mol Cell Biol. 1989 Nov;9(11):5022–5033. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.11.5022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HSU T. C., SOMERS C. E. Properties of L cells resistant to 5-bromodeoxyuridine. Exp Cell Res. 1962 Mar;26:404–410. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(62)90192-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbomel P. From gene to chromosome: organization levels defined by the interplay of transcription and replication in vertebrates. New Biol. 1990 Nov;2(11):937–945. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J. E., Wold B. J., Hauschka S. D. Muscle creatine kinase sequence elements regulating skeletal and cardiac muscle expression in transgenic mice. Mol Cell Biol. 1989 Aug;9(8):3393–3399. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.8.3393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassar A. B., Davis R. L., Wright W. E., Kadesch T., Murre C., Voronova A., Baltimore D., Weintraub H. Functional activity of myogenic HLH proteins requires hetero-oligomerization with E12/E47-like proteins in vivo. Cell. 1991 Jul 26;66(2):305–315. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90620-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luckow B., Schütz G. CAT constructions with multiple unique restriction sites for the functional analysis of eukaryotic promoters and regulatory elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987 Jul 10;15(13):5490–5490. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.13.5490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mar J. H., Ordahl C. P. A conserved CATTCCT motif is required for skeletal muscle-specific activity of the cardiac troponin T gene promoter. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988 Sep;85(17):6404–6408. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.17.6404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellon I., Bhorjee J. S. Isolation and characterization of nuclei and purification of chromatin from differentiating cultures of rat skeletal muscle. Exp Cell Res. 1982 Jan;137(1):141–154. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(82)90016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minty A. J., Alonso S., Caravatti M., Buckingham M. E. A fetal skeletal muscle actin mRNA in the mouse and its identity with cardiac actin mRNA. Cell. 1982 Aug;30(1):185–192. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minty A., Kedes L. Upstream regions of the human cardiac actin gene that modulate its transcription in muscle cells: presence of an evolutionarily conserved repeated motif. Mol Cell Biol. 1986 Jun;6(6):2125–2136. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.6.2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miwa T., Kedes L. Duplicated CArG box domains have positive and mutually dependent regulatory roles in expression of the human alpha-cardiac actin gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1987 Aug;7(8):2803–2813. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.8.2803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navankasattusas S., Zhu H., Garcia A. V., Evans S. M., Chien K. R. A ubiquitous factor (HF-1a) and a distinct muscle factor (HF-1b/MEF-2) form an E-box-independent pathway for cardiac muscle gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1992 Apr;12(4):1469–1479. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.4.1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson E. N. MyoD family: a paradigm for development? Genes Dev. 1990 Sep;4(9):1454–1461. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.9.1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ordahl C. P. Developmental regulation of sarcomeric gene expression. Curr Top Dev Biol. 1992;26:145–168. doi: 10.1016/s0070-2153(08)60444-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piette J., Klarsfeld A., Changeux J. P. Interaction of nuclear factors with the upstream region of the alpha-subunit gene of chicken muscle acetylcholine receptor: variations with muscle differentiation and denervation. EMBO J. 1989 Mar;8(3):687–694. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03427.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quantin B., Perricaudet L. D., Tajbakhsh S., Mandel J. L. Adenovirus as an expression vector in muscle cells in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992 Apr 1;89(7):2581–2584. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.7.2581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralph P., Nakoinz I. Phagocytosis and cytolysis by a macrophage tumour and its cloned cell line. Nature. 1975 Oct 2;257(5525):393–394. doi: 10.1038/257393a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reznikoff C. A., Brankow D. W., Heidelberger C. Establishment and characterization of a cloned line of C3H mouse embryo cells sensitive to postconfluence inhibition of division. Cancer Res. 1973 Dec;33(12):3231–3238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruezinsky D., Beckmann H., Kadesch T. Modulation of the IgH enhancer's cell type specificity through a genetic switch. Genes Dev. 1991 Jan;5(1):29–37. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartorelli V., Hong N. A., Bishopric N. H., Kedes L. Myocardial activation of the human cardiac alpha-actin promoter by helix-loop-helix proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992 May 1;89(9):4047–4051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.9.4047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartorelli V., Webster K. A., Kedes L. Muscle-specific expression of the cardiac alpha-actin gene requires MyoD1, CArG-box binding factor, and Sp1. Genes Dev. 1990 Oct;4(10):1811–1822. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.10.1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassoon D. A., Garner I., Buckingham M. Transcripts of alpha-cardiac and alpha-skeletal actins are early markers for myogenesis in the mouse embryo. Development. 1988 Sep;104(1):155–164. doi: 10.1242/dev.104.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seed B., Sheen J. Y. A simple phase-extraction assay for chloramphenicol acyltransferase activity. Gene. 1988 Jul 30;67(2):271–277. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90403-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapscott S. J., Davis R. L., Thayer M. J., Cheng P. F., Weintraub H., Lassar A. B. MyoD1: a nuclear phosphoprotein requiring a Myc homology region to convert fibroblasts to myoblasts. Science. 1988 Oct 21;242(4877):405–411. doi: 10.1126/science.3175662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J. F., Hayes L. S., Lloyd D. B. Modulation of firefly luciferase stability and impact on studies of gene regulation. Gene. 1991 Jul 22;103(2):171–177. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90270-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treisman R. The serum response element. Trends Biochem Sci. 1992 Oct;17(10):423–426. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(92)90013-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub H., Davis R., Tapscott S., Thayer M., Krause M., Benezra R., Blackwell T. K., Turner D., Rupp R., Hollenberg S. The myoD gene family: nodal point during specification of the muscle cell lineage. Science. 1991 Feb 15;251(4995):761–766. doi: 10.1126/science.1846704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wentworth B. M., Donoghue M., Engert J. C., Berglund E. B., Rosenthal N. Paired MyoD-binding sites regulate myosin light chain gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991 Feb 15;88(4):1242–1246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.4.1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter B. B., Arnold H. H. Tissue-specific DNase I-hypersensitive sites and hypomethylation in the chicken cardiac myosin light chain gene (L2-A). J Biol Chem. 1987 Oct 5;262(28):13750–13757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright W. E., Binder M., Funk W. Cyclic amplification and selection of targets (CASTing) for the myogenin consensus binding site. Mol Cell Biol. 1991 Aug;11(8):4104–4110. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.8.4104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yutzey K. E., Kline R. L., Konieczny S. F. An internal regulatory element controls troponin I gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1989 Apr;9(4):1397–1405. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.4.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]