Abstract

Mapping of epitopes recognized by functional monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) is essential for understanding the nature of immune responses and designing improved vaccines, therapeutics, and diagnostics. In recent years, identification of B-cell epitopes targeted by neutralizing antibodies has facilitated the design of peptide-based vaccines against highly variable pathogens like HIV, respiratory syncytial virus, and Helicobacter pylori; however, none of these products has yet progressed into clinical stages. Linear epitopes identified by conventional mapping techniques only partially reflect the immunogenic properties of the epitope in its natural conformation, thus limiting the success of this approach. To investigate antigen–antibody interactions and assess the potential of the most common epitope mapping techniques, we generated a series of mAbs against factor H binding protein (fHbp), a key virulence factor and vaccine antigen of Neisseria meningitidis. The interaction of fHbp with the bactericidal mAb 12C1 was studied by various epitope mapping methods. Although a 12-residue epitope in the C terminus of fHbp was identified by both Peptide Scanning and Phage Display Library screening, other approaches, such as hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (MS) and X-ray crystallography, showed that mAb 12C1 occupies an area of ∼1,000 Å2 on fHbp, including >20 fHbp residues distributed on both N- and C-terminal domains. Collectively, these data show that linear epitope mapping techniques provide useful but incomplete descriptions of B-cell epitopes, indicating that increased efforts to fully characterize antigen–antibody interfaces are required to understand and design effective immunogens.

Keywords: meningococcus, structure, surface plasmon resonance, structural mass spectrometry, antigen-antibody complex

For over 30 years, scientists have been trying to design improved vaccines against pathogens that could not be addressed using conventional approaches, by using synthetic peptides, phage display libraries, or mimotopes recognized by polyclonal or monoclonal Abs to guide attempts to mimic protective B-cell epitopes. This approach has been used to design peptide vaccines against several viral pathogens, including HIV (1), Dengue virus (2), and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) (3), for which no effective vaccines have been available, and also, bacterial pathogens like Helicobacter pylori (4). However, although T-cell epitopes are usually short peptides lacking defined structure, B-cell epitopes have more complex, 3D structures often composed of residues that are discontinuous in the primary structure. Therefore, immunization with an isolated synthetic peptide is unlikely to elicit high titers of neutralizing antibodies. Conventional approaches have been used to identify epitopes recognized by Palivizumab, a mAb used to prevent RSV infections (5), and other neutralizing antibodies against the RSV F glycoprotein. The epitope targeted by the neutralizing antibody 101F was mapped to a 12-residue region of glycoprotein F; however, the binding affinity of mAb 101F to this peptide was 16,000-fold lower than to the full-length protein (3). Subsequent structural studies indicated that residues outside the linear epitope were required for high-affinity binding. Therefore, although the rational design of vaccines based on immunodominant peptide epitopes might be valuable in principle, to date, this approach has not resulted in a vaccine that has made significant progress in clinical trials. The RSV example suggests that one of the major reasons for failure is a limited understanding of the structure of B-cell epitopes, a knowledge gap of growing importance.

To address this issue, we generated a mAb against factor H binding protein (fHbp), a key virulence factor of Neisseria meningitidis, and characterized their interactions using multiple epitope mapping techniques and site-directed mutagenesis. fHbp is a 28 kDa surface-exposed lipoprotein and an important component of two meningococcal vaccines currently in clinical development (6–9). fHbp plays a prominent role in meningococcal pathogenesis by recruiting human factor H (hfH) to the bacterial surface, thus protecting the bacterium from complement-mediated killing (10–12). fHbp is expressed by the majority of virulent meningococcal strains; its sequence displays extensive variability, allowing classification into three main variant groups (var1, -2, and -3) or two subfamilies (A and B) sharing limited cross-protection (13).

Several previous epitope mapping studies have been performed on fHbp using NMR spectroscopy (14, 15), scanning of synthetic peptide arrays (16), and phage- or yeast-display techniques (17–19). The interpretation of these studies was facilitated by the 3D structures of fHbp alone (20, 21) or in complex with hfH (22). More recently, structures of fHbp var2 and -3 in complex with hfH have been reported (23). Collectively, these studies identified residues critical for specific binding by anti-var1, -2, and -3 antibodies, suggesting that many epitopes are located within regions of diversity of the protein, consistent with diversifying selection. Among the mAbs described so far, some can inhibit the fHbp:fH interaction, indicating that they recognize epitopes within the fH binding region. However, a detailed structural understanding of the interaction between fHbp and a mAb is still lacking.

Here, we characterized the interaction between fHbp and mAb 12C1, which displayed the interesting properties of specifically recognizing fHbp var1, inhibiting fHbp binding to hfH, and exhibiting bactericidal activity. Identification of the fHbp epitope targeted by 12C1 was attempted in various ways. Our results show that different approaches give different pictures of the same epitope and that hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (MS) (HDX-MS) was the most effective method to rapidly supply near-complete information about epitope structure. However, only X-ray crystallography provided the fine molecular details of the antigen–antibody interaction. A structure-based dissection of the interface by site-directed mutagenesis showed that engineering single amino acids within the epitope is rarely sufficient to impact epitope recognition, suggesting that the entire epitope area needs to be considered when engineering novel candidate antigens. This multidisciplinary study allowed an extensive comparison of various epitope mapping approaches and highlighted the reliability of HDX-MS and X-ray crystallography for epitope mapping.

Results

mAb 12C1, a Bactericidal mAb Specific for fHbp var1.

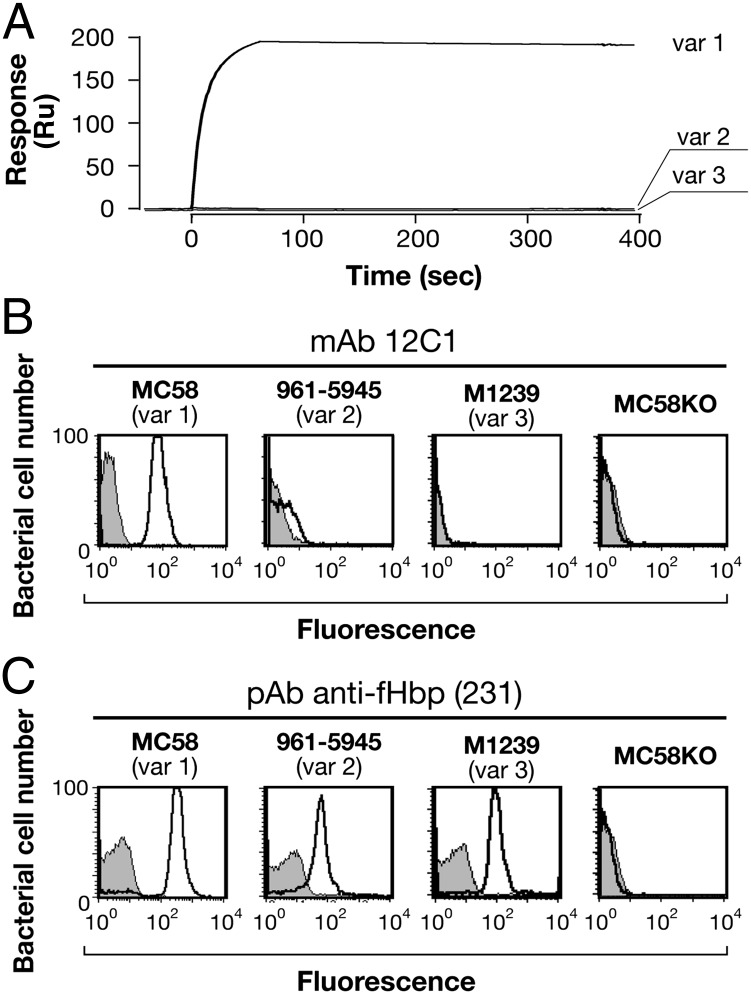

fHbp is composed of N- and C-terminal β-barrel domains spanning amino acids 1–137 and 138–255, respectively. The murine IgG2b isotype mAb 12C1 was obtained by immunization of CD1 mice with a fusion protein containing the three main variants of fHbp (var1, -2, and -3) followed by standard hybridoma techniques (Materials and Methods). Binding of purified mAb 12C1 to recombinant fHbp var1, -2, and -3 was assessed by surface plasmon resonance (SPR) assays, revealing that mAb 12C1 specifically recognizes fHbp var1 but not var2 or -3 (Fig. 1A). The SPR data were also in agreement with FACS analyses performed on three live encapsulated serogroup B meningococcal strains, MC58, 961–5945, and M1239, respectively expressing a distinct fHbp from var1, -2, and -3. Using mAb 12C1, a positive FACS signal was obtained only with strain MC58 (var1) (Fig. 1B), whereas polyclonal antiserum raised against the fHbp fusion protein could detect fHbp on the surface of each of the three strains used (Fig. 1C). In both cases, no signal was obtained for an MC58 strain lacking the fHbp gene. Furthermore, when mAb 12C1 was tested against the three meningococcal strains in a serum bactericidal assay (SBA) using baby rabbit complement (no activity was observed using human complement), a bactericidal titer of 1:2,048 was obtained against strain MC58. In contrast, the other two strains, which express fHbp variants not recognized by mAb 12C1, were resistant to killing.

Fig. 1.

mAb 12C1 recognizes specifically fHbp var1. (A) SPR sensorgrams of fHbp var1, -2, and -3 injected over mAb 12C1. (B) In FACS analyses, mAb 12C1 only reacted with MC58, which expresses fHbp var1. No recognition was observed for strains expressing fHbp var2 or -3 or a MC58 strain lacking fHbp (MC58KO). (C) A polyclonal antiserum was FACS-positive against meningococcal strains expressing each of the three variants. As expected, the MC58KO strain is negative. The strain name and fHbp variant expressed by each strain are shown above each panel.

Peptide Scanning and Phage Display Analyses Identify a C-Terminal Peptide Epitope.

A synthetic library of overlapping dodecapeptides spanning the entire fHbp var1 sequence was tested for binding to mAb 12C1 as described previously (16). This epitope mapping approach revealed that one dodecapeptide, residues 238AEVKTVNGIRHI249 within the C terminus of fHbp, was recognized by mAb 12C1 (Fig. S1).

To confirm these results, a library of fragments (average size = 170 bp) from the fHbp var1 gene was constructed for display on the M13 filamentous phage. The resulting library was highly representative of antigen sequence and produced protein fragments of average size of 55 aa displayed through fusion to the major coat protein (pVIII) in a two-gene phagemid system. Screening of the phage display library with mAb 12C1 revealed many positive clones corresponding to a panel of three immunoreactive recombinant inserts encoding different but overlapping fHbp peptides of 28, 33, and 42 residues (Fig. S1). Notably, each of the three clones encompassed a common stretch of 27 residues (L224-G250), which contains the dodecapeptide A238-I249 as identified in the peptide array experiment.

Recombinant C-Terminal Domain of fHbp Binds mAb 12C1 with Lower Affinity.

SPR single-cycle kinetic titrations revealed a high-affinity interaction (KD < 0.05 nM) between fHbp var1 and mAb 12C1. In contrast, a shorter protein encompassing the C-terminal β-barrel domain of fHbp bound to mAb 12C1 over 400 times more weakly (Table 1 and Fig. S2). Although association rates were similar, there was a marked difference in dissociation from 12C1, which was faster for the C-terminal β-barrel construct. Moreover, a synthetic dodecapeptide overlapping with the peptide-scanning derived peptide (A238-I249) tested for binding to mAb 12C1 in an SPR assay displayed a KD > 1 mM that was ∼106-fold weaker than the interaction with full-length fHbp (Fig. S3). Overall, SPR revealed that mAb 12C1 binds full-length fHbp with high affinity, and the affinity decreases for the recombinant C-terminal domain and is extremely low for the synthetic peptide.

Table 1.

SPR-derived binding affinities of mAb 12C1 for recombinant fHbp var1 proteins (original sensorgrams in Figs. S2 and S8)

| kon (M−1s−1) | koff (s−1) | KD (nM) | KD-mutants/KD-WT* | |

| fHbp | ||||

| WT | 1.03 × 106 | 2.99 × 10−5 | 0.03 ± 0.006 | 1 |

| β-barrel | 8.18 × 105 | 1.2 × 10−2 | 14.4 ± 0.5 | 480* |

| Mutants | ||||

| R130L | 1.3 × 106 | 1.0 × 10−3 | 0.80 ± 0.03 | 25* |

| K241A | — | — | —† | — |

| V243G | 7.4 × 106 | 0.5 × 10−3 | 0.65 ± 0.08 | 22* |

| 3M‡ | 7.4 × 105 | 1.0 × 10−4 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 5* |

| 5M§ | 1.0 × 106 | 3.6 × 10−3 | 3.4 ± 0.02 | 110* |

*The KD reduction is shown as x-fold obtained from the ratio KD-mutants/KD-WT.

†No interaction detected under tested conditions.

‡3M: fHbp var1 triple mutant E239T+N244E+H248E.

§5M: fHbp var1 quintuple mutant R130L+N215G+E239T+N244E+H248E.

Three N-Terminal and One C-Terminal Epitope Fragments Identified by HDX-MS Analyses.

Next, HDX-MS was used to map the 12C1:fHbp interface. The HDX approach is based on the differential rate of deuterium incorporation by a protein when it is bound or not by its ligand. The rate at which backbone amide hydrogens exchange in solution is directly dependent on the dynamics and structure of the protein. Therefore, regions embedded within the structure or occluded by the presence of a ligand will exchange more slowly than regions fully exposed to the solvent (24).

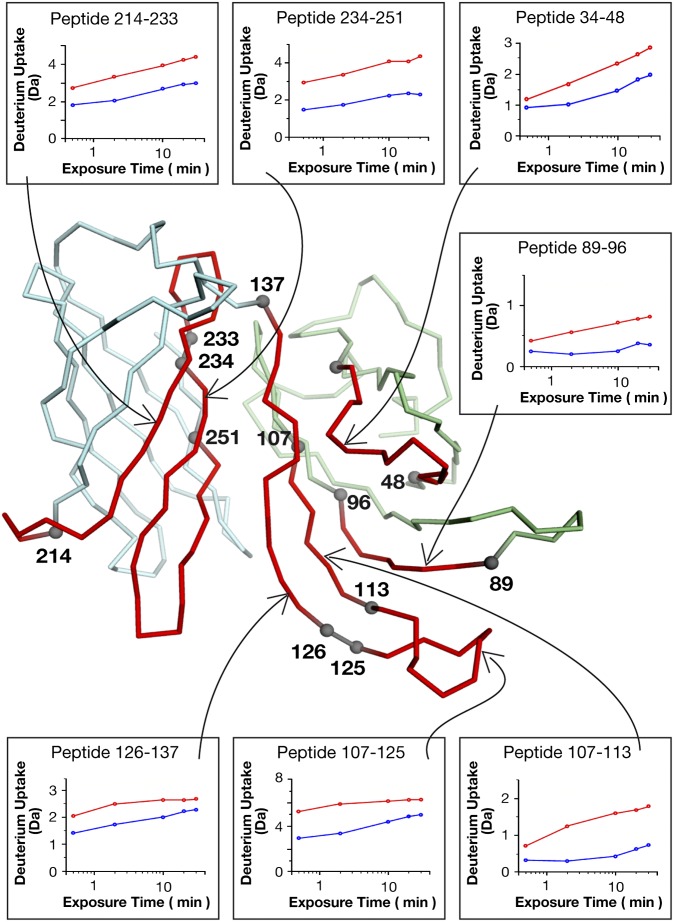

Epitope mapping by HDX-MS was performed in two steps as described previously (25). First, a reference experiment was performed in which deuterium (D) incorporation into fHbp alone was monitored by MS. The extent of deuterium incorporation was mapped for 19 peptide fragments, covering 97% of the fHbp sequence. Second, a similar experiment was performed in the presence of mAb 12C1. HDX-MS revealed that H–D exchange was reduced in presence of mAb 12C1 for 7 of 19 fHbp fragments. These partially overlapping peptides defined four discontinuous segments (L34-L48, I89-F96, T107-137, and Y214-L251) encompassing 92 residues distributed in the N- and C-terminal domains of fHbp and clustered in a distinct region (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Results of epitope mapping by HDX-MS. Boxes show deuterium uptake data over 30 min for fHbp fragments in the absence (red) or presence (blue) of mAb 12C1. Each hydrogen/deuterium exchange generates a mass shift of 1 Da. Deuterium incorporation was reduced by mAb 12C1 for each fragment shown. The peptides protected by mAb 12C1 in the HDX-MS analysis are highlighted in red on the fHbp structure. Numbered spheres indicate the start/end of each affected fragment.

As observed for the peptide above, no binding was detected in SPR assays using a synthetic peptide (Q110-M123) identified by HDX-MS (Fig. S3), suggesting that the structure and/or context of these peptides is crucial for their interaction with mAb 12C1.

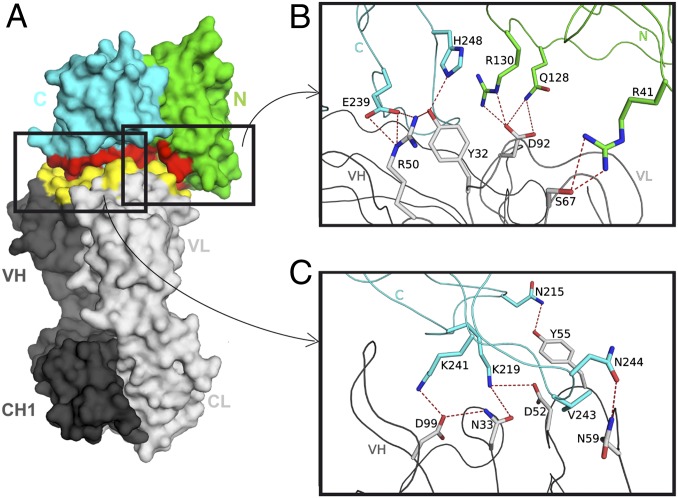

Fab 12C1:fHbp Crystal Structure Reveals the Conformational Nature of the Epitope.

To fully characterize the interaction, the structure of the fHbp:Fab 12C1 complex was determined by X-ray crystallography. Electron density was observed for almost the entire complex (Fig. S4), allowing model building and structure refinement at 1.8 Å resolution (Table S1). Considered separately, the fHbp and Fab structures show no major differences from those structures reported previously. The structure of the complex reveals that both the N- and C-terminal domains of the antigen engage in extensive interactions with the variable heavy (VH) and variable light (VL) domains of the Fab (Fig. 3). Intriguingly, complementarity determining region (CDR)-L3 and all three CDR loops of the heavy chain create a four-sided calyx-like scaffold that grips the C-terminal β-barrel (Fig. S5). The VH domain exclusively contacts the C-terminal β-barrel, whereas the VL domain recognizes both N- and C-terminal domains.

Fig. 3.

The crystal structure of fHbp bound to Fab 12C1. (A) Surface plot of the fHbp:Fab 12C1 complex (size ∼110 × 55 × 50 Å). N- and C-terminal domains of fHbp are green and cyan, respectively. VH and VL chains of Fab 12C1 are dark and light gray, respectively. Interfacing residues are red for fHbp and yellow for 12C1. (B) An enlargement showing key interactions in the interface between VL and the N- and C-terminal fHbp domains colored as in A. Dashed lines show fHbp side-chain intermolecular H bonds or salt bridges <4 Å. (C) As in B, showing details of the VH:C-terminal fHbp domain interaction. The fHbp/Fab 12C1 complex at 5 mg/mL crystallized in 20% (wt/vol) PEG 3350 and 0.2 M ammonium sulfate. X-ray diffraction data were collected at the Swiss Light Source.

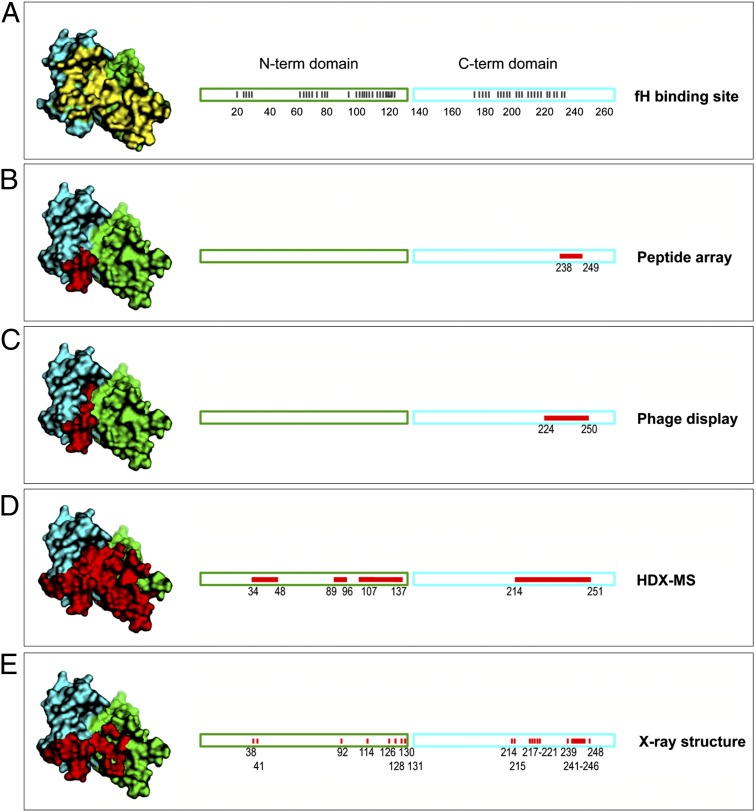

The crystal structure provides a map of the antibody–antigen interface at atomic resolution. The interface involves 23 fHbp residues and 33 Fab residues, burying surface patches of ∼1,000 Å2 on fHbp and ∼880 Å2 on Fab 12C1. The following fHbp residues make direct hydrogen bonds and/or salt bridges with 12C1: R41, Q128, R130, N215, K219, S221, E239, K241, T242, N244, I246, and H248; however, V243 makes a large hydrophobic contact (Fig. 3). Only R41, Q128, and R130 are contributed by the N-terminal domain of fHbp. On the C-terminal domain, residues S221, E239, and T242-H248 are contacted by both VL and VH chains. The C-terminal peptide (A238-I249) described above is contained within the interface. More importantly, all four peptides identified by HDX-MS are also present in the epitope revealed by X-ray crystallography (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Summary of the fHbp epitopes mapped by different techniques. Surface (Left) and linear (Right) representations of fHbp with N- and C-terminal domains in green and cyan, respectively. A shows the fHbp residues contacted by fH in yellow. (B–E) Red patches highlight epitope mapping data, namely (B) the dodecameric peptide A238-I249 identified in the synthetic peptide library, (C) the 27-mer peptide L224-G250 identified by phage display, (D) peptide regions mapped by HDX-MS, and (E) residues contacted by Fab 12C1 in the crystal structure. In the linear maps, red bars show residues making intermolecular contacts.

Fab 12C1 and fH Bind to Overlapping Regions on fHbp var1.

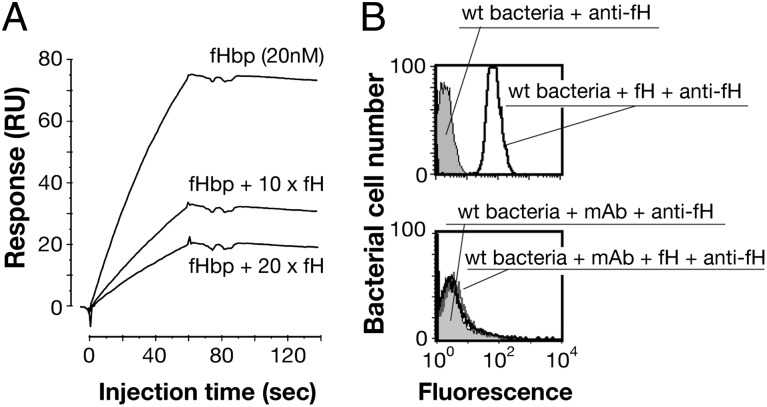

A structural comparison of the complexes of fHbp with Fab 12C1 or hfH (22) revealed that the binding sites for 12C1 and hfH overlap considerably (Fig. 4 and Fig. S6). Indeed, 15 of 23 fHbp residues in the interface with 12C1 overlap with the fH binding site. In particular, 8 of 15 residues overlap with the panel of 11 residues recently reported to be crucial for the high-affinity interaction of fH with fHbp var1 (23). To investigate the potentially mutually exclusive binding of these two proteins to fHbp, an SPR competition experiment was performed, wherein the binding of mAb 12C1 to fHbp was inhibited by preincubation of fHbp with hfH in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5A). In contrast, hfH had no effect on binding to mAb 502, which binds a distal region of fHbp (15, 26). The competition was confirmed by FACS analysis on live bacterial cells, which showed that binding of fHbp by hfH on the meningococcal surface was inhibited by addition of mAb 12C1 (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

mAb 12C1 inhibits fHbp binding to fH. (A) SPR sensorgrams showing injections of fHbp (20 nM) over a surface displaying mAb 12C1; binding was inhibited by increasing amounts of fH. (B) FACS analyses on live bacteria revealed that binding of fHbp by fH on the meningococcal surface was inhibited by the addition of mAb 12C1.

To identify crucial residues within the fHbp:12C1 interface, a library of 46 fHbp var1 single-point mutants located in the fH binding site (22, 23) was screened by SPR, revealing that only the K241A mutation strongly reduced binding. When injected over captured mAb 12C1, the K241A mutant showed no detectable binding (Table 1); interestingly, this residue is contained within the epitope identified by the peptide array and phage-display screens, confirming the importance of this region in the interaction with the mAb. Structural analyses also support the key role of this residue, because the side chain of K241 engages in extensive interactions with the Fab by forming a salt bridge and two H bonds with the heavy chain of 12C1. In contrast, data recently published have not identified K241 as a key residue for fHbp var1 binding to hfH (23). Indeed, K241 plays a much less crucial role in the interface with hfH, wherein it makes only one H bond and no salt bridges (22). Because of the tight interaction of the A238-I249 loop with 12C1, in the fHbp:12C1 complex, this loop is pulled toward the Fab, revealing an intrinsic mobility of the loop likely stabilized upon interaction with the binding partner.

fHbp:12C1 Interface Contains Multiple Determinants of Specificity and Affinity.

Despite the crucial role played by K241 in fHbp var1 binding to mAb 12C1, a multiple sequence alignment (Fig. S7) shows that this residue is conserved among the three fHbp variants, and therefore, mutations in this position cannot explain the specificity of mAb 12C1 for var1 fHbp. To better understand the molecular basis underlying the variant-specific binding exhibited by mAb 12C1 (Fig. 1A), the epitope mapping data were analyzed. Detailed inspection of the fHbp:Fab12C1 interface revealed that, of all the fHbp var1 residues making side chain-mediated polar contacts with Fab 12C1, a subset of only five was not conserved in main var2 or -3; these were residues R130L, N215G, E239T, N244E, and H248E (Fig. S7). Interestingly, three of these residues map within the dodecapeptide epitope identified above. To test whether these differences might underlie the variant specificity of the interaction, several mutants of fHbp var1 were prepared. The structural integrity of each mutant was confirmed by differential scanning calorimetry (Fig. S7). As determined by SPR assays, the triple mutant (E239T+N244E+H248E) displayed only fivefold weaker binding, the single mutants R130L and V243G showed >20-fold weaker binding, and the simultaneous introduction of five mutations (R130L+N215G+E239T+N244E+H248E) resulted in >100-fold weaker binding to mAb 12C1 (Table 1 and Fig. S8). Overall, these results confirm that the dodecapeptide A238-I249 is necessary but not sufficient for high-affinity binding to the mAb.

Discussion

A complete understanding of immunogenic B-cell epitopes is essential when trying to develop improved vaccines against pathogens displaying antigenic variability (27). Such information can be derived from several epitope mapping approaches (28). However, most conventional techniques are limited, because they detect interactions between a mAb and a single short continuous stretch of residues of the antigen, which may or may not adopt relevant secondary or tertiary structure, thus being unable to faithfully mimic complex protein conformations. Here, we used a comprehensive set of empirical epitope mapping techniques to investigate the molecular basis for the binding of a bactericidal mAb, mAb 12C1, to fHbp, a potent meningococcal vaccine antigen (6–9).

As shown by SPR and FACS analysis, mAb 12C1 was highly specific for fHbp var1. Given the extensive sequence diversity of fHbp, identification of anti-fHbp mAbs displaying variant-restricted specificity is not unusual, particularly for FACS-positive mAbs, because most of the fHbp variability is associated with surface-exposed regions (17). Consequently, only serogroup B meningococcal strains expressing var1 fHbp were sensitive to rabbit complement-mediated bactericidal activity exerted by mAb 12C1. In contrast, no killing was observed when human complement was used. This result was not anticipated, because the high affinity of this mAb for fHbp might have been expected to prevent binding of hfH (present at high concentration in human serum) to the bacteria, thus resulting in uncontrolled activation of the alternative complement cascade and ultimately, enhanced bacterial killing (29). Additional work will be required to investigate the reasons underlying this lack of SBA activity, which has been observed for other mAbs (18). One possible explanation could be the low density of the epitope on the meningococcal surface, which could result in an insufficient amount of mAb 12C1 immune complex to engage C1q and activate the classical complement cascade. Furthermore, binding of the mAb to the bacterial surface might not be sufficient to compete with the comparatively higher amount of hfH, which could, therefore, bind fHbp and prevent binding of the mAb to its target antigen.

From a library of synthetic peptides, a single C-terminal fHbp peptide (A238-I249) emerged as the primary target recognized by mAb 12C1. Accordingly, screening a phage-display library of fHbp peptides identified a 27-residue peptide (L224-G250) as a target of mAb 12C1. Overall, the two approaches provide concordant results and indicate the presence of a single continuous epitope within the region L224-G250 apparently sufficient for binding to mAb 12C1. However, SPR data revealed that the C-terminal domain of fHbp was not sufficient for high-affinity binding, suggesting that additional regions on the N-terminal domain were required for binding.

The typical antibody binding surface of an antigen covers 800–2,000 Å2; therefore, it is very likely that a substantial portion of an antigen is involved in the interaction (27, 30). Indeed, the HDX-MS approach not only confirmed the involvement of peptide A238-I249 in binding 12C1 but also revealed additional fHbp N-terminal regions mediating the interaction. Overall, these results provided an explanation of the SPR data and supported the evidence of a conformational epitope spanning the N and C termini of fHbp as the target of mAb 12C1.

Since the first structure determination of an antibody-antigen complex four decades ago (31), it has been clear that cocrystal structures can provide an unambiguous definition of the epitope and paratope atoms forming the interface. Indeed, the crystal structure of the Fab 12C1:fHbp complex determined herein allowed an atomic-level description of the extensive antigen–antibody interface. Notably, mAb 12C1 binds to a region of fHbp that overlaps significantly with the fH binding site and encompasses R41 on the N-terminal domain and E239 on the C-terminal domain, both of which are known to be important for fH binding. Furthermore, recent data identified residues crucial for high-affinity interaction of fH with each of three main fHbp variants (23). It is remarkable that, among 11 residues listed as key determinants for high-affinity interaction of fHbp var1 to hfH, 8 residues are also found in the fHbp:12C1 interface. Given this significant overlap, it is not surprising that the binding of fHbp to fH was inhibited by addition of mAb 12C1, although structural data show that Fab 12C1 is not a structural mimic of fH. Moreover, the affinity of fHbp to mAb 12C1 (KD < 0.05 nM) is remarkably higher than the affinity reported for fHbp to hfH (5–45 nM) (22, 27, 32, 33), thus explaining the observed capacity of mAb 12C1 to displace fH from the fHbp:hfH complex. The crystal structure, together with multiple sequence alignments, also indicated a subset of fHbp residues potentially responsible for the var1 binding specificity of mAb 12C1. Indeed, the simultaneous mutation of all five residues resulted in a strong decrease in binding affinity but did not abolish binding completely, suggesting that the large two-domain binding interface observed in the structure contains multiple determinants of specificity and affinity rather than being dependent on a small number of hot-spot residues. Interestingly, mutation of three key residues within the short peptide A238-I249 identified by the linear epitope mapping techniques does not result in substantially decreased binding, confirming the importance of the entire interface for the high-affinity interaction.

Collectively, our results highlight the importance of using sensitive epitope mapping techniques rather than relying on the identification of linear peptides when seeking to fully understand the details of B-cell epitopes mediating antigen–antibody interactions. The insights obtained here are important regarding both this specific fHbp–mAb 12C1 interaction and the field of epitope mapping more generally. Indeed, epitope mapping is of particular importance in the context of N. meningitidis, an extracellular pathogen against which the main protective response depends on circulating antibodies. Now, as we start to understand the principles of the rational design of protein structures (34), the correct definition of epitopes has become extremely important. Finally, these findings may pave the way to approach the challenges of modern vaccinology, namely the engineering of immunodominant epitopes able to induce broad immunity against all natural forms of sequence-variable pathogens, such as N. meningitidis, malaria, influenza, and HIV.

Materials and Methods

For each section below, full details can be found in SI Materials and Methods.

Antibody Generation.

A hybridoma cell line expressing mAb 12C1 was obtained after immunization of CD1 mice with a recombinant fusion protein comprised of main fHbp var1, -2, and -3 from serogroup B N. meningitidis strains MC58, 961–5945, and M1239, respectively.

Molecular Biology and Protein Purification.

mAb 12C1 was prepared by Areta International. The 12C1 Fab fragment was prepared by papain digestion of mAb 12C1 followed by Protein A-mediated purification. All fHbp proteins were produced in Escherichia coli and purified by C-terminal 6-His tags, desalting, and anionic exchange chromatography steps.

SBA.

SBA was performed using pooled baby rabbit sera (CedarLane) as complement source to test bactericidal activity of mAb 12C1 (stock concentration = 2.7 mg/mL) to different strains of N. meningitidis as previously reported (16). The bactericidal titer is expressed as the reciprocal of the stock dilution yielding ≥50% bactericidal killing.

SPR.

SPR experiments were performed on a Biacore T200 instrument at 25 °C in 10 mM potassium phosphate buffer, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% (vol/vol) P20 surfactant, pH 7.4. SPR data were analyzed using the 1:1 Langmuir binding model.

FACS Analysis.

FACS analyses for detection of the 12C1:fHbp interaction and study of inhibition of the fH:fHbp interaction were performed as described in SI Materials and Methods.

Epitope Mapping by Synthetic Peptide Array and Phage Display.

Details of the epitope mapping experiments investigating the interaction of mAb 12C1 with fHbp peptides are provided in SI Materials and Methods.

HDX-MS.

Deuterium labeling of the fHbp/mAb 12C1 complex was performed at 25 °C in deuterated PBS with a pD of 7.4. Samples were periodically removed and quenched at pH 2.4, and they were injected into a nanoACQUITY UPLC with HDX technology (Waters). Mass spectra of desalted peptic fragments purified by reverse-phase ultraperformance liquid chromatography (RP-UPLC) were acquired in resolution mode (m/z 100–2,000) on a SynaptG2 mass spectrometer with a standard electrospray ionization source. Peptide identities were confirmed by MSE (Mass Spectrometry elevated energy) analysis. Data were processed using Protein Lynx Global Server 2.5 and manually confirmed. DynamX software (Waters) was used to select peptides for analysis and extract each centroid mass as a function of labeling time.

Protein Crystallization and Structure Determination.

Crystals belonged to space group P212121, with one complex per asymmetric unit. The structure was determined by molecular replacement using three search models: fHbp from Protein Data Bank ID code 2W80 and Fab coordinates from Protein Data Bank ID codes 1KB5 and 3LIZ. Refinement and model building were performed with Phenix (35) and COOT (36).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Marchi, W. Pansegrau, C. Zambonelli, G. Corsi (graphics), E. Settembre, M.M. Giuliani, M. Nissum, and P. Costantino for their support at Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics srl; G. Teti and C. Beninati for assistance with Phage Display; and L. Lozzi (University of Siena) for Peptide Array work. The laboratories of S.M.L. and C.M.T. are supported by the Medical Research Council, the Wellcome Trust, and the Oxford Martin School.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The sponsor is a full-time employee of Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics.

Data deposition: Coordinates of the Fab 12C1:fHbp complex structure have been deposited in the RCSB Protein Database (accession no. 2YPV).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1222845110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Correia BE, et al. Computational design of epitope-scaffolds allows induction of antibodies specific for a poorly immunogenic HIV vaccine epitope. Structure. 2010;18(9):1116–1126. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tian Y, et al. Identification of B cell epitopes of dengue virus 2 NS3 protein by monoclonal antibody. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-4419-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McLellan JS, et al. Structure of a major antigenic site on the respiratory syncytial virus fusion glycoprotein in complex with neutralizing antibody 101F. J Virol. 2010;84(23):12236–12244. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01579-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guo L, et al. Immunological features and efficacy of the reconstructed epitope vaccine CtUBE against Helicobacter pylori infection in BALB/c mice model. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-4486-1. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson S, et al. Development of a humanized monoclonal antibody (MEDI-493) with potent in vitro and in vivo activity against respiratory syncytial virus. J Infect Dis. 1997;176(5):1215–1224. doi: 10.1086/514115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson AS, Jansen KU, Eiden J. New frontiers in meningococcal vaccines. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2011;10(5):617–634. doi: 10.1586/erv.11.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bai X, Findlow J, Borrow R. Recombinant protein meningococcal serogroup B vaccine combined with outer membrane vesicles. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2011;11(7):969–985. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2011.585965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Serruto D, Bottomley MJ, Ram S, Giuliani MM, Rappuoli R. The new multicomponent vaccine against meningococcal serogroup B, 4CMenB: Immunological, functional and structural characterization of the antigens. Vaccine. 2012;30(Suppl 2):B87–B97. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.01.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Toneatto D, et al. Early clinical experience with a candidate meningococcal B recombinant vaccine (rMenB) in healthy adults. Hum Vaccin. 2011;7(7):781–791. doi: 10.4161/hv.7.7.15997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Madico G, et al. The meningococcal vaccine candidate GNA1870 binds the complement regulatory protein factor H and enhances serum resistance. J Immunol. 2006;177(1):501–510. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schneider MC, et al. Functional significance of factor H binding to Neisseria meningitidis. J Immunol. 2006;176(12):7566–7575. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.12.7566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seib KL, et al. Factor H-binding protein is important for meningococcal survival in human whole blood and serum and in the presence of the antimicrobial peptide LL-37. Infect Immun. 2009;77(1):292–299. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01071-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Masignani V, et al. Vaccination against Neisseria meningitidis using three variants of the lipoprotein GNA1870. J Exp Med. 2003;197(6):789–799. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mascioni A, et al. Structural basis for the immunogenic properties of the meningococcal vaccine candidate LP2086. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(13):8738–8746. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808831200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scarselli M, et al. Epitope mapping of a bactericidal monoclonal antibody against the factor H binding protein of Neisseria meningitidis. J Mol Biol. 2009;386(1):97–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giuliani MM, et al. The region comprising amino acids 100 to 255 of Neisseria meningitidis lipoprotein GNA 1870 elicits bactericidal antibodies. Infect Immun. 2005;73(2):1151–1160. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.2.1151-1160.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beernink PT, Granoff DM. Bactericidal antibody responses induced by meningococcal recombinant chimeric factor H-binding protein vaccines. Infect Immun. 2008;76(6):2568–2575. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00033-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beernink PT, LoPasso C, Angiolillo A, Felici F, Granoff D. A region of the N-terminal domain of meningococcal factor H-binding protein that elicits bactericidal antibody across antigenic variant groups. Mol Immunol. 2009;46(8–9):1647–1653. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vu DM, Pajon R, Reason DC, Granoff DM. A broadly cross-reactive monoclonal antibody against an epitope on the N-terminus of meningococcal fHbp. Sci Rep. 2012;2:341. doi: 10.1038/srep00341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cantini F, et al. Solution structure of the factor H-binding protein, a survival factor and protective antigen of Neisseria meningitidis. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(14):9022–9026. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C800214200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cendron L, Veggi D, Girardi E, Zanotti G. Structure of the uncomplexed Neisseria meningitidis factor H-binding protein fHbp (rLP2086) Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun. 2011;67(Pt 5):531–535. doi: 10.1107/S1744309111006154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schneider MC, et al. Neisseria meningitidis recruits factor H using protein mimicry of host carbohydrates. Nature. 2009;458(7240):890–893. doi: 10.1038/nature07769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson S, et al. Design and evaluation of meningococcal vaccines through structure-based modification of host and pathogen molecules. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(10):e1002981. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hager-Braun C, Tomer KB. Determination of protein-derived epitopes by mass spectrometry. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2005;2(5):745–756. doi: 10.1586/14789450.2.5.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brier S, et al. Structural insight into the mechanism of DNA-binding attenuation of the Neisserial adhesin repressor NadR by the small natural ligand 4-hydroxyphenylacetic acid. Biochemistry. 2012;51(34):6738–6752. doi: 10.1021/bi300656w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giuntini S, Beernink PT, Reason DC, Granoff DM. Monoclonal antibodies to meningococcal factor H binding protein with overlapping epitopes and discordant functional activity. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e34272. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scarselli M, et al. Rational design of a meningococcal antigen inducing broad protective immunity. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3(91):91ra62. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ladner RC. Mapping the epitopes of antibodies. Biotechnol Genet Eng Rev. 2007;24:1–30. doi: 10.1080/02648725.2007.10648092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Giuntini S, Reason DC, Granoff DM. Complement-mediated bactericidal activity of anti-factor H binding protein monoclonal antibodies against the meningococcus relies upon blocking factor H binding. Infect Immun. 2011;79(9):3751–3759. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05182-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davies DR, Cohen GH. Interactions of protein antigens with antibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93(1):7–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Segal DM, et al. The three-dimensional structure of a phosphorylcholine-binding mouse immunoglobulin Fab and the nature of the antigen binding site. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1974;71(11):4298–4302. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.11.4298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dunphy KY, Beernink PT, Brogioni B, Granoff DM. Effect of factor H-binding protein sequence variation on factor H binding and survival of Neisseria meningitidis in human blood. Infect Immun. 2011;79(1):353–359. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00849-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seib KL, et al. Characterization of diverse subvariants of the meningococcal factor H (fH) binding protein for their ability to bind fH, to mediate serum resistance, and to induce bactericidal antibodies. Infect Immun. 2011;79(2):970–981. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00891-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koga N, et al. Principles for designing ideal protein structures. Nature. 2012;491(7423):222–227. doi: 10.1038/nature11600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: A comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66(Pt 2):213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60(Pt 12 Pt 1):2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.