Abstract

Background

Reperfusion following ischemia leads to neutrophil recruitment injured tissue. Selectins and β2 integrins regulate neutrophil interaction with the endothelium during neutrophil rolling and firm adhesion. Excessive neutrophil infiltration into tissue is thought to contribute to IRI damage. NaHS mitigates the damage caused by ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI). This study's objective was to determine the effect of hydrogen sulfide (NaHS) on neutrophil adhesion receptor expression.

Methods

Human neutrophils were either left untreated or incubated in 20 μM NaHS, and/or 50 μg/mL pharmacological ADAM-17 inhibitor TAPI-0; activated by IL-8, fMLP, or TNF-α; and labeled against PSGL-1, LFA-1, Mac-1 α, L-selectin and β2 integrin epitopes CBRM1/5 or KIM127 for flow cytometry. Cohorts of 3 C57BL/6 mice received an intravenous dose of saline vehicle, or 20 μM NaHS with or without 50 μg/mL TAPI-0 before unilateral tourniquet induced hind-limb ischemia for 3 hours followed by 3 hours of reperfusion. Bilateral gastrocnemius muscles were processed for histology before neutrophil infiltration quantification.

Results

NaHS treatment significantly increased L-selectin shedding from human neutrophils following activation by fMLP and IL-8 in an ADAM-17 dependent manner. Mice treated with NaHS to raise bloodstream concentration by 20 μM prior to ischemia or reperfusion showed a significant reduction in neutrophil recruitment into skeletal muscle tissue following tourniquet-induced hindlimb IRI.

Conclusions

NaHS administration results in the downregulation of L-selectin expression in activated human neutrophils. This leads to a reduction in neutrophil extravasation and tissue infiltration and may partially account for the protective effects of NaHS seen in the setting of IRI.

Introduction

Ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI) occurs when oxygenated blood flow is restored to hypoxic tissue and can cause irreversible tissue damage following trauma, cardiac arrest, cerebrovascular accident, or surgical procedures.1-3 IRI can occur in skeletal muscle during elective surgery (i.e. lower extremity revascularization) or unexpectedly (i.e. due to arterial thrombosis). Though pharmaceutical treatments have been developed to prevent the tissue damage associated with ischemia and reperfusion,4,5 current clinical practice focuses primarily on reducing the duration of ischemia.

Neutrophils or polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) are predominantly the first leukocytes to infiltrate the site of injury and contribute to the pathogenesis of IRI.6-10 Leukocytes roll, facilitated by selectin adhesion interactions, along the endothelium before firmly adhering to it and then crawl along the blood vessel wall to sites of transendothelial migration near wounds or infections (Figure 1).11 Interleukin-1β (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-8 (IL-8), and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) are up-regulated as a result of IRI.12 These chemical mediators activate neutrophils, which shed L-selectin from their surface, and endothelial cells, creating an inflamed blood vessel wall to which leukocytes bind via β2 integrins LFA-1 (CD11a/CD18) and Mac-1 (CD11b/CD18) through interaction with endothelial ICAM-1 prior to diapedesis.11

Figure 1. HS treatment modifies neutrophil tissue infiltration.

Following injury, pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines released by damaged tissue attract neutrophils from the bloodstream. E- and P-selectin on the blood vessel wall interact with L-selectin to recruit neutrophils from the bloodstream, causing them to roll on the endothelium, shedding L-selectin as they roll. The neutrophil β2-integrins form firm adhesions with endothelial ICAM-1, enabling the leukocytes to crawl and migrate into the injured tissue. The present work suggests that following treatment with HS, neutrophils roll on the endothelium, losing L-selectin too quickly to allow the formation of firm adhesions and infiltration into the injured tissue. This reduction in neutrophil infiltration may contribute to the protective effect observed when HS is administered to treat IRI.

L-selectin is constitutively expressed at the tips of microvilli on the neutrophil surface and is a key participant in neutrophil tethering and subsequent rolling.13 It binds proteins modified by mucin-type O-linked oligosaccharides found on the endothelial surface of high venules in lymph nodes and inflamed blood vessels.14,15 In addition, L-selectin modulates secondary leukocyte recruitment via interaction with P-selectin glycoprotein ligand 1 (PSGL-1) expressed on leukocytes.16 Mice deficient in L-selectin showed impaired leukocyte recruitment into inflamed endothelium, virtually no lymphocyte migration into the lymph nodes, and impaired neutrophil sequestration in the microvasculature of the lungs in the presence of bacterially-induced pneumonia.17,18

L-selectin expression is tightly regulated by ectodomain cleavage from the cell surface via TNF-α-converting enzyme (TACE or ADAM-17) protease activity.19-21 Stimulus by mechanical stress, receptor crosslinking, or exposure to IL-8, PMA, LPS, TNF- α, or fMLP leads to L-selectin shedding.19,22-25 The inhibition of L-selectin shedding increases leukocyte recruitment 26. Mice with ADAM-17 conditionally knocked out exhibit reduced L-selectin shedding and increased neutrophil adhesion to the blood vessel wall, modifying the inflammatory response of mice enough to significantly increase the survival rate of those with peritoneal sepsis.20

Though historically thought of as a toxic environmental gas,27 hydrogen sulfide (HS) has shown promise as a therapeutic agent to counter damage in cardiac, brain, intestinal, skeletal muscle, and hepatic tissue caused by IRI.28-32 It suppresses neutrophil calcium-dependent cytoskeletal activity including chemotaxis and granule release33 and reduced fMLP-induced leukocyte adhesion to mesenteric microcirculation and suppressed neutrophil infiltration in response to carrageenan-induced inflammation.34,35 These studies have not addressed the effect of HS on leukocyte adhesion and infiltration in skeletal muscle following IRI. A deeper understanding of selectin-mediated cell signaling and leukocyte recruitment will yield a better understanding of the role the innate immune system plays in the healing process, and may lead to the development of clinical practices that reduce inflammation in a way that promotes rapid, complete patient recovery.

L-selectin mediated adhesion and cell signaling are thought to be responsible for the localization of leukocytes following injury. In this paper we describe an examination of the effect of HS treatment on the neutrophil expression of L-selectin in human neutrophils in vitro and its consequent effect on neutrophil infiltration into tissue resulting from IRI in a murine model in vivo.

Materials and Methods

Please refer to Materials and Methods in the Supplemental Digital Content (insert link) for further details on reagents and procedures. Neutrophils were isolated from whole human blood collected, as described in Materials and Methods in the Supplemental Digital Content, after informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and with the approval of Cornell Institutional Review Board for Human Participants.

In vitro neutrophil activation

Both NaHS-treated and untreated neutrophils were incubated with 5 nM IL-8 , 20 nM TNF-α (R&D Systems Inc.), or 5 nM fMLP (Sigma-Aldrich) to determine the effect of NaHS treatment on β2 integrin and L-selectin expression during neutrophil activation. For L-selectin quantification, cells were incubated at room temperature for 5 minutes for IL-8 and fMLP, 60 minutes with TNF-α, or left unactivated with or without 30 μM TAPI-0 or 100 nM SB203580. These concentrations of TAPI-0 and SB203580 were shown to be effective in previous studies.25 All samples were subsequently prepared for flow cytometry analysis. To quantify β2 integrin expression and activation, untreated and NaHS treated neutrophils were incubated with 5 nM IL-8, 5 nM fMLP, 20 nM TNF-α, or left unactivated for 30 min at 37°C. Following cellular activation, cells were prepared for and analyzed by flow cytometry as described in the supplemental Materials and Methods (insert link). Experiments were conducted using neutrophils from at least three different donors.

In vivo studies

Eight-week old male C57Bl/6 mice (Jackson Laboratory) were used for in vivo studies. All animal care and experimental procedures were in compliance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals 36 and were approved by the Weill Cornell Medical College Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC # 2010-0071).

Reagent preparation for in vivo experiments

NaHS was dissolved in sterile phosphate buffered saline to a final concentration of 20 mM prior to injection into mice. TAPI-0 (Peptides International) was dissolved in 10 mg/mL dimethyl sulfoxide (Electron Microscopy Sciences) and diluted with PBS to a final concentration of 1μg/mL.

Murine hind limb ischemia-reperfusion model

Twenty-four mice were anesthetized via an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (150 mg/kg) and xylazine (15 mg/kg). Hindlimb ischemia was performed as previously described.37 Briefly, a tourniquet was applied to the right hindlimb proximal to the greater trochanter, thereby occluding blood flow to distal tissues. The contralateral left leg served as a non-ischemic control. After 3 hours of ischemia, the tourniquet was removed and the ischemic limb was allowed to reperfuse. Reperfusion was confirmed by the rapid onset of limb hyperemia. Following 3 hours of reperfusion, all mice were euthanized by carbon dioxide asphyxiation and cervical dislocation, and the bilateral gastrocnemius muscles were harvested.

Treatment groups

Mice were randomized to 8 treatment groups: either 20 minutes prior to the onset of ischemia or 20 minutes prior to the onset of reperfusion, mice received via tail vein injection 200 μL PBS containing 0 or 1.96 μg NaHS and 0 or 150 μg TAPI-0 (n=3 for each group). The HS dose was based upon an estimated murine circulating blood volume of 7% of 25 g, or 1.75 mL. A 1.96 μg dose of NaHS would therefore raise the final bloodstream concentration by 20 μM. TAPI-0 dosage was based upon the study by Hafezi-Moghadam et al., 2001, equivalent to a final TAPI-0 bloodstream concentration to 50 μg/mL.

Tissue processing and imaging

Muscle specimens were washed in PBS, fixed in 10% buffered formalin for 24 hours, dehydrated, and embedded in paraffin. Ten-micrometer sections of all samples were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E).

Bright field images of H&E stained samples were taken using an Olympus BX50 (Olympus America) microscope with an Olympus UPlanFL 40x/1.30 Oil objective (Olympus America) using a Moticam 2300 3.0M Pixel camera. Pictures were acquired using Motic Images Plus 2.0 (Motic China Group Co.) software. Scale bars were added to the images using ImageJ 1.44n (U. S. National Institutes of Health). Twenty images from three different sections of each mouse were collected to make a pool of sixty images per hind-limb per mouse, one limb having undergone ischemia and the other was a non-ischemic control. Five randomly selected images from each mouse were selected from the pool of sixty available images and analyzed blinded to group identity to quantify neutrophil infiltration into the tissue.

Statistical analysis

Rolling velocity and L-selectin and β2 integrin expression data were plotted and analyzed using Prism 5.0b for Microsoft (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, www.graphpad.com) using two-tailed paired t-tests with a significance level of α=0.05. Neutrophil tissue infiltration data were also plotted in Prism 5.0b for Microsoft (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, www.graphpad.com) and analyzed using a one-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey post-test.

Results

HS treatment does not change adhesion molecule expression, or β2 integrin activation of human neutrophils

L-selectin, PSGL-1, sialyl Lewis-x, CD11a, and CD11b play key roles in the transient rolling and formation of firm adhesions of neutrophils to the blood vessel wall,38 but showed no change in expression levels following treatment with 20 μM NaHS (Supplemental Figure 1 A-E (insert link)). Additionally, HS did not produce any significant change in neutrophil rolling velocity through sialyl Lewis-x coated microtubes designed to simulate healthy post-capillary venules (data not shown), and it did not significantly change the extent of conformational change in CD11b to expose the CBRM1/5 epitope characteristic of activated integrins in resting cells (Supplemental Figure 1 F (insert link)). The formation of firm adhesions of leukocytes to the blood vessel wall is required to facilitate transendothelial migration.11 We found that treatment with HS had no significant effect on β2 integrin expression or conformational change on human neutrophils following activation with fMLP, IL-8, or TNF-α (data not shown). Together, these in vitro results imply that the reduction in induced neutrophil recruitment observed after HS treatment in vivo is not due to a change in adhesion molecule expression, rolling velocity, or β2 integrin activation.

ADAM-17 mediated L-selectin down-regulation is augmented by exposure to HS

L-selectin is responsible for the initial capture and rolling of neutrophils along the blood vessel wall.38 L-selectin can be down-regulated in an ADAM-17 dependent or independent manner.21 We found that HS treatment of human neutrophils in vitro leads to a significant increase in L-selectin shedding following activation with fMLP or IL-8, but not TNF-α, when the pH is maintained at 7.4 using HEPES (Figure 2). Neutrophils were treated with ADAM-17 inhibitor TAPI-0 or p38 MAP kinase inhibitor SB203580 to determine whether the increase in L-selectin shedding following HS was dependent on either ADAM-17 or p38 MAP kinase, respectively. Figure 2 demonstrates that HS-modulated L-selectin shedding is highly dependent on ADAM-17 activity during activation with fMLP, IL-8, or TNF- α. However, p38 MAP kinase inhibition only resulted in a significant change in L-selectin shedding in the setting of neutrophil activation by fMLP or TNF-α, but not IL-8 (Figure 2). This result is consistent with work by others in showing that fMLP and TNF-α induced signaling in neutrophils is p38 MAP kinase dependent.39 These results taken together indicate that HS pretreatment leads to an increase in ADAM-17 dependent L-selectin shedding upon activation by fMLP, IL-8, and TNF-α.

Figure 2. HS treatment modifies L-selectin shedding from activated human neutrophils.

NaHS treated and untreated neutrophils were incubated with either the ADAM-17 inhibitor TAPI-0 or p38 MAP kinase inhibitor SB203580. The cells were then activated with IL-8, fMLP, or TNF-α prior to flow cytometry quantification of L-selectin expression. pH = 7.4. n=5 human donors. Error bars are s.e.m..

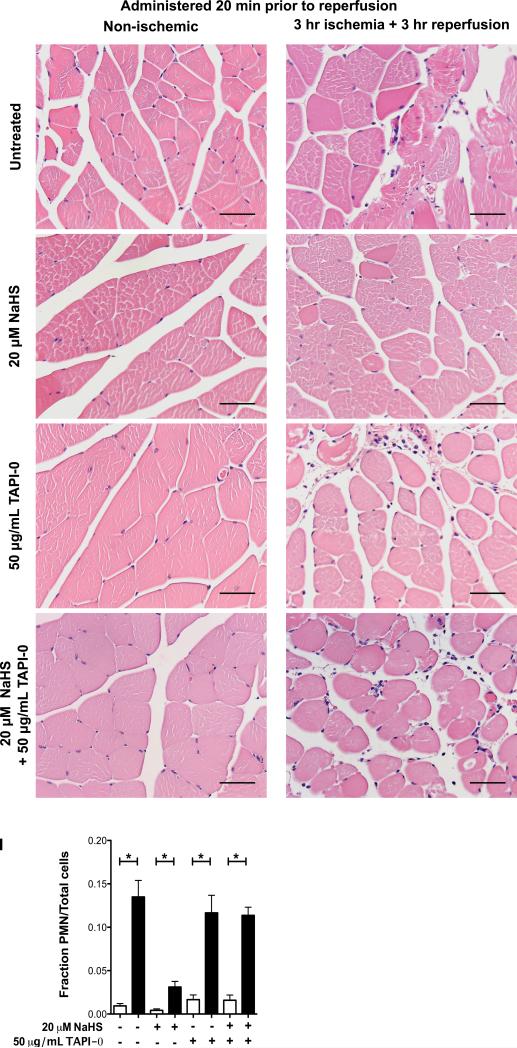

HS administration reduces neutrophil tissue infiltration into skeletal muscle following hindlimb ischemia and subsequent reperfusion

The extent of neutrophil infiltration into an injured tissue following IRI can be correlated with the extent of tissue damage incurred.8 In the present work, histology was utilized to determine whether the timing of HS administration imparts a significant effect on the extent of neutrophil infiltration into tissue subjected to IRI. Previous work shows that the concentration and timing of HS administration is key for tissue preservation.37,40 HS administration significantly reduced neutrophil infiltration into the ischemic-reperfused tissue, regardless of whether HS was administered 20 minutes prior to ischemia or 20 minutes prior to reperfusion (Figure 3 A-D and Figure 4 A-D). However, there was no significant difference between samples from mice that received the HS treatment 20 minutes prior to the onset of ischemia compared with those that received the same treatment 20 minutes prior to reperfusion.

Figure 3. Neutrophil infiltration into skeletal muscle when HS is administered prior to ischemia and reperfusion.

Mice were treated with either saline (untreated) (A, B), NaHS (C, D), ADAM-17 inhibitor TAPI-0 (E, F), or NaHS and TAPI-0 (G, H) 20 minutes prior to the induction of unilateral hind-limb ischemia followed by 3 hours of reperfusion. H&E stained histology samples were obtained from both the non-ischemic (A, C, E, G) and ischemic hindlimbs (C, D, F, H). The number of neutrophils infiltrating the tissue was quantified based on nuclear shape and calculated as a fraction of the total number of nuclei present in each picture (I). P-values determined using a two-tailed t-test. * p<0.05, NS = not significant. Scale bar = 50 μm. n=3 mice per treatment group. Error bars are s.e.m..

Figure 4. ADAM-17 inhibition reverses the protective effect of HS in ischemic tissue.

Mice were treated with either saline (untreated) (A, B), NaHS (C, D), ADAM-17 inhibitor TAPI-0 (E, F), or NaHS and TAPI-0 (G, H) 20 minutes prior to reperfusion, following 3 hours of unilateral hind-limb ischemia. Neutrophil infiltration into the tissue was quantified based on nuclear shape and calculated as a fraction of the total number of nuclei present in each picture (I). Samples were stained with H&E. P-values determined using a two-tailed t-test. * p<0.05, NS = not significant. Scale bar = 50 μm. n=3 mice per treatment group. Error bars are s.e.m..

ADAM-17 inhibition leads to an increase in neutrophil tissue infiltration in vivo

Mice were treated with the ADAM-17 inhibitor TAPI-0 or a combination of TAPI-0 and HS in order to confirm that the reduction in neutrophil tissue infiltration due to HS treatment was indeed both L-selectin and ADAM-17 dependent. Histologic analysis confirmed that the extent of neutrophil infiltration into hindlimb skeletal muscle subjected to IRI was not different between in mice treated with TAPI-0 alone, TAPI-0 and HS, or vehicle alone (Figure 3 E-H and Figure 4 E-H). These results corroborate the in vitro studies that demonstrate HS has a significant effect on neutrophil tissue infiltration following ischemia and subsequent reperfusion by modulating L-selectin shedding through ADAM-17 proteolytic activity.

Discussion

This study is the first to examine the role of HS in modulating neutrophil recruitment into skeletal muscle following IRI. These results show that, in vitro, treatment of human neutrophils with HS significantly increases the rate of L-selectin shedding from the cell surface during activation by IL-8 and fMLP regardless of whether the cells were exposed to a physiological or slightly basic pH environment. Given that L-selectin shedding is one of the key molecules that regulates leukocyte recruitment into tissue during inflammation,26 it follows that neutrophil infiltration would decrease as a result of HS treatment in a murine model of IRI (Figure 1).

L-selectin ectodomain cleavage is not necessarily ADAM-17 dependent.41 However, both in vitro and in vivo results in this study indicate that neutrophil recruitment into ischemic-reperfused tissue is heavily dependent on ADAM-17 function. During ischemia and reperfusion ADAM-17 is also responsible for the cleavage of transmembrane forms of TNF-αand IL-6 in hepatic IRI models.42,43 While HS treatment leads to reduced serum levels of pro-inflammatory compounds such as nitric oxide and TNF-α in such models, it is unclear whether the reduction in TNF-α expression takes places at the transcriptional level or at the time of release by ADAM-17.44 The current study indicates that neutrophil recruitment into previously ischemic tissue is reduced due to HS treatment, but increases as a result of ADAM-17 inhibition. The reduction in neutrophil recruitment in the presence of HS could be a direct result of rapid L-selectin cleavage from the neutrophil surface upon neutrophil exposure to cytokines before the leukocytes are able to roll on the blood vessel wall. A hindrance in this first step of neutrophil recruitment could lead to a decrease in neutrophil infiltration into sites of injury. Our in vivo results are mirrored in vitro where HS treatment increases L-selectin down-regulation unless ADAM-17 is inhibited. These findings show that ADAM-17 plays an important role in the inflammatory cascade triggered by IRI in skeletal muscle and agree with work conducted in intestinal and hepatic tissue in suggesting that ADAM-17 plays an important role in the pathogenesis of IRI.42,43 Further investigation would be required in order to determine the effect of HS treatment on ADAM-17 activity in non-neutrophil cell types.

During the course of an inflammatory response neutrophils infiltrate the site of injury within minutes.45 They release reactive oxygen species and pro-inflammatory cytokines that can contribute further injury to already damaged tissue.46,47 While HS effects have also been shown to reduce apoptosis and promote cell survival through mitochondrial pathways,48 reduced recruitment of leukocytes could contribute in part to the reduction in the extent of injury in ischemia-reperfusion models.

Of note, there was no significant change in neutrophil tissue infiltration when the HS treatment was administered before reperfusion as opposed to when HS was administered prior to the induction of ischemia. These findings agree with the observation that HS administration 20 minutes before ischemia or the onset of reperfusion also reduces the extent of tissue damage in the same hind-limb IRI model.40 Rabbits exposed to HS fumes take up to 4 hours to metabolize HS in the blood stream and up to 24 hours to clear thiosulfate, one of the primary HS metabolites.49 This could explain why the administration of HS prior to ischemia is still as protective as cases where is HS administered only prior to reperfusion. This flexibility in time of administration would enable clinicians to treat patients in situations of anticipated ischemia (i.e. microvascular free tissue transfer or organ transplantation) or unanticipated ischemia (i.e. thrombotic arterial occlusion or myocardial infarction).

Conclusion

IRI is the result of the combined effects of hypoxia within the tissue, damage by reactive oxygen species, and the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines that regulate immune response. The cytoprotection credited to HS has at least in part been attributed to its reaction with reactive oxygen species and its ability to reduce the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines in injured tissue. The role of endogenous and exogenous HS in immune cell signaling has yet to be fully elucidated. This study showed that HS therapy has a significant and important effect on the modulation of neutrophil L-selectin expression and leads to a reduction in neutrophil recruitment into injured tissue following skeletal muscle IRI.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Jeff Mattison for his assistance with donor recruitment and sample collection. The National Institutes of Health grant number HL018128, Plastic Surgery Educational Foundation Pilot Research Grant #137371, and Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (Kirschstein-NRSA) Institutional Research Training Grant T32 HL083824 05 funded this work.

Abbreviations

- ADAM-17

also known as TACE (TNF-α-converting enzyme)

- DPBS

Dubelcco's Phosphate Buffered Saline

- fMLP

N-formyl-methionine-leucine-phenylalanine

- HBSS

Hank's Buffered Salt Solution

- HS

Hydrogen Sulfide

- IL-1β

Interleukin-1β

- IL-6

interleukin-6

- IL-8

interleukin-8

- IRI

Ischemia-reperfusion injury

- PMN

polymorphonuclear leukocytes or neutrophils

- PSGL-1

P-selectin glycoprotein ligand 1

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor α

Footnotes

- Biomedical Engineerng Society Annual Meeting, Hartford, Connecticut, October 2011

- Plastic Surgery Research Council Annual Meeting, Louisville, Kentucky, April 2011

- Academic Surgical Council Annual Meeting, Huntington Beach, California, February 2011

- American College of Surgeons Clinical Congress, San Fransisco, California, October 2011

Financial Disclosure:

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

Products: Sodium hydrogen sulfide (NaHS) is used in this manuscript to prevent ischemia-reperfusion injury.

Level of Evidence: Basic science and animal study. There is no assigned level of evidence for this work.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.McCord JM. Oxygen-derived free radicals in postischemic tissue injury. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:159–163. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198501173120305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yilmaz G, Granger DN. Leukocyte recruitment and ischemic brain injury. Neuromolecular Med. 2010;12:193–204. doi: 10.1007/s12017-009-8074-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yan HD, Zhang F, Kochevar AJ, et al. The Effect of Postconditioning on the Muscle Flap Survival After Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury in Rats. J Invest Surg. 2010;23:249–256. doi: 10.3109/08941931003615529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ergun Y, Darendeli S, Imrek S, et al. The comparison of the effects of anesthetic doses of ketamine, propofol, and etomidate on ischemia-reperfusion injury in skeletal muscle. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2010;24:215–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2009.00748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cowled PA, Khanna A, Laws PE, et al. Simvastatin plus nitric oxide synthase inhibition modulates remote organ damage following skeletal muscle ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Invest Surg. 2008;21:119–126. doi: 10.1080/08941930802046501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Putte B, Kesecioglu J, Hendriks J, et al. Cellular infiltrates and injury evaluation in a rat model of warm pulmonary ischemia-reperfusion. Crit Care. 2005;9:R1–R8. doi: 10.1186/cc2992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feuerstein GZ, Wang X, Barone FC. The role of cytokines in the neuropathology of stroke and neurotrauma. Neuroimmunomodulation. 1998;5:143–159. doi: 10.1159/000026331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kochanek PM, Hallenbeck JM. Polymorphonuclear leukocytes and monocytes/macrophages in the pathogenesis of cerebral ischemia and stroke. Stroke. 1992;23:1367–1379. doi: 10.1161/01.str.23.9.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyle EM, Jr., Kovacich JC, Hebert CA, et al. Inhibition of interleukin-8 blocks myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1998;116:114–121. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(98)70249-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kawata H, Sawatari K, Mayer JE., Jr. Evidence for the role of neutrophils in reperfusion injury after cold cardioplegic ischemia in neonatal lambs. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1992;103:908–917. discussion 917-908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sumagin R, Prizant H, Lomakina E, et al. LFA-1 and Mac-1 define characteristically different intralumenal crawling and emigration patterns for monocytes and neutrophils in situ. J Immunol. 2010;185:7057–7066. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saini HK, Xu Y-J, Zhang M, et al. Role of tumour necrosis factor-alpha and other cytokines in ischemia-reperfusion-induced injury in the heart. Exp Clin Cardiol. 2005;10:213–222. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.von Andrian UH, Chambers JD, Berg EL, et al. L-selectin mediates neutrophil rolling in inflamed venules through sialyl Lewis-x- dependent and -independent recognition pathways. Blood. 1993;82:182–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fukuda M, Hiraoka N, Yeh J-C. C-Type Lectins and Sialyl Lewis X Oligosaccharides. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:467–470. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.3.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang L, Fuster M, Sriramarao P, et al. Endothelial heparan sulfate deficiency impairs L-selectin- and chemokine-mediated neutrophil trafficking during inflammatory responses. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:902–910. doi: 10.1038/ni1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McEver RP, Cummings RD. Perspectives Series: Cell Adhesion in Vascular Biology. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:485–492. doi: 10.1172/JCI119556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doyle NA, Bhagwan SD, Meek BB, et al. Neutrophil margination, sequestration, and emigration in the lungs of L-selectin-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:526–533. doi: 10.1172/JCI119189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tedder TF, Steeber DA, Pizcueta P. L-selectin-deficient mice have impaired leukocyte recruitment into inflammatory sites. J Exp Med. 1995;181 doi: 10.1084/jem.181.6.2259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walcheck B, Herrera AH, St Hill C, et al. ADAM17 activity during human neutrophil activation and apoptosis. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:968–976. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Long C, Wang Y, Herrera AH, et al. In vivo role of leukocyte ADAM17 in the inflammatory and host responses during E. coli-mediated peritonitis. J Leukoc Biol. 2010;87:1097–1101. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1109763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smalley DM, Ley K. L-selectin: mechanisms and physiological significance of ectodomain cleavage. J Cell Mol Med. 2005;9:255–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2005.tb00354.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fan H, Derynck R. Ectodomain shedding of TGF-α and other transmembrane proteins is induced by receptor tyrosine kinase activation and MAP kinase signaling cascades. EMBO J. 1999;18:6962–6972. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.24.6962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jutila MA, Rott L, Berg EL, et al. Function and regulation of the neutrophil MEL-14 antigen in vivo: comparison with LFA-1 and Mac-1. J Immunol. 1989;143:3318–3324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palecanda A, Walcheck B, Bishop DK, et al. Rapid activation-independent shedding of leukocyte L-selectin induced by crosslinking of the surface antigen. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:1279–1286. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830220524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee D, Schultz JB, Knauf PA, et al. Mechanical shedding of L-selectin from the neutrophil surface during rolling on sialyl Lewis x under flow. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:4812–4820. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609994200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hafezi-Moghadam A, Thomas KL, Prorock AJ, et al. L-selectin shedding regulates leukocyte recruitment. J Exp Med. 2001;193:863–872. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.7.863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gregorakos L, Dimopoulos G, Liberi S, et al. Hydrogen sulfide poisoning: management and complications. Angiology. 1995;46:1123–1131. doi: 10.1177/000331979504601208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Henderson PW, Singh SP, Belkin D, et al. Hydrogen sulfide protects against ischemia-reperfusion injury in an in vitro model of cutaneous tissue transplantation. J Surg Res. 2010;159:451–455. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2009.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Henderson PW, Weinstein AL, Sung J, et al. Hydrogen sulfide attenuates ischemia-reperfusion injury in in vitro and in vivo models of intestine free tissue transfer. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125:1670–1678. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181d4fdc5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kimura Y, Dargusch R, Schubert D, et al. Hydrogen sulfide protects HT22 neuronal cells from oxidative stress. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:661–670. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bliksoen M, Kaljusto ML, Vaage J, et al. Effects of hydrogen sulphide on ischaemia-reperfusion injury and ischaemic preconditioning in the isolated, perfused rat heart. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008;34:344–349. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sivarajah A, Collino M, Yasin M, et al. Anti-apoptotic and anti-inflammatory effects of hydrogen sulfide in a rat model of regional myocardial I/R. Shock. 2009;31:267–274. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318180ff89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mariggio MA, Pettini F, Fumarulo R. Sulfide influence on polymorphonuclear functions: a possible role for Ca2+ involvement. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 1997;19:393–404. doi: 10.3109/08923979709046984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zanardo RCO, Brancaleone V, Distrutti E, et al. Hydrogen sulfide is an endogenous modulator of leukocyte-mediated inflammation. FASEB J. 2006;20:2118–2120. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6270fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fiorucci S, Antonelli E, Distrutti E, et al. Inhibition of hydrogen sulfide generation contributes to gastric injury caused by anti-inflammatory nonsteroidal drugs. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1210–1224. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.07.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources . N. R. C. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. National Academy of Sciences; Washington, DC: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Henderson PW, Singh SP, Weinstein AL, et al. Therapeutic metabolic inhibition: hydrogen sulfide significantly mitigates skeletal muscle ischemia reperfusion injury in vitro and in vivo. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:1890–1898. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181f446bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ley K, Laudanna C, Cybulsky MI, et al. Getting to the site of inflammation: the leukocyte adhesion cascade updated. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:678–689. doi: 10.1038/nri2156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zu YL, Qi JF, Gilchrist A, et al. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation is required for human neutrophil function triggered by TNF-alpha or FMLP stimulation. J Immunol. 1998;160:1982–1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Henderson PW, Jimenez N, Ruffino J, et al. Therapeutic delivery of hydrogen sulfide for salvage of ischemic skeletal muscle after the onset of critical ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53:785–791. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.10.094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walcheck B, Alexander SR, St. Hill CA, et al. ADAM-17-independent shedding of L-selectin. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;74:389–394. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0403141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tang ZY, Loss G, Carmody I, et al. TIMP-3 ameliorates hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury through inhibition of tumor necrosis factor-alpha-converting enzyme activity in rats. Transplantation. 2006;82:1518–1523. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000243381.41777.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ichikawa Y, Miura T, Nakano A, et al. The role of ADAM protease in the tyrosine kinase-mediated trigger mechanism of ischemic preconditioning. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;62:167–175. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kang K, Zhao MY, Jiang HC, et al. Role of Hydrogen Sulfide in Hepatic Ischemia-Reperfusion-Induced Injury In Rats. Liver Transpl. 2009;15:1306–1314. doi: 10.1002/lt.21810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kaplanski G, Marin V, Montero-Julian F, et al. IL-6: a regulator of the transition from neutrophil to monocyte recruitment during inflammation. Trends Immunol. 2003;24:25–29. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)00013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fujishima S, Hoffman AR, Vu T, et al. Regulation of neutrophil interleukin 8 gene expression and protein secretion by LPS, TNF-alpha, and IL-1 beta. J Cell Physiol. 1993;154:478–485. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041540305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tidball JG. Inflammatory processes in muscle injury and repair. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;288:R345–R353. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00454.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Elrod JW, Calvert JW, Morrison J, et al. Hydrogen sulfide attenuates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by preservation of mitochondrial function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:15560–15565. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705891104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kage S, Nagata T, Kimura K, Kudo K, Imamura T. Usefulness of thiosulfate as an indicator of hydrogen sulfide poisoning in forensic toxicological examination: A study with animal experiments. Jap J Forensic Toxicol. 1992;10:223–227. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.