Abstract

We analyze simple morphological configurations that represent gap-junctional coupling between neuronal processes or between muscle fibers. Specifically, we use cable theory and simulations to examine the consequences of current flow from one cable to other gap-junctionally coupled passive cables. When the proximal end of the first cable is voltage clamped, the amplitude of the electrical signal in distal portions of the second cable depends on the cable diameter. However, this amplitude does not simply increase if cable diameter is increased, as expected from the larger length constant; instead, an optimal diameter exists. The optimal diameter arises because the dependence of voltage attenuation along the second cable on cable diameter follows two opposing rules. As cable diameter increases, the attenuation decreases due to a larger length constant yet increases because of a reduction in current density arising from the limiting effect of the gap junction on current flow into the second cable. The optimal diameter depends on the gap junction resistance and cable parameters. In branched cables, dependence on diameter is local and thus may serve to functionally compartmentalize branches that are coupled to other cells. Such compartmentalization may be important when periodic signals or action potentials cause the current flow across gap junctions.

Keywords: Model, gap junction, cable theory, coupling, voltage clamp

Introduction

A number of recent publications have reported the presence of gap-junctional coupling between many neuronal types that had not previously been observed (Connors and Long 2004). These studies highlight the growing importance attributed to gap junctions in the computations performed by many regions of the nervous system. The role of gap junctions in the generation and failure of neuronal oscillations and synchrony has been the subject of many theoretical studies (Bem and Rinzel 2004; Kepler et al. 1990; Kopell and Ermentrout 2004; LeBeau et al. 2003; Sherman and Rinzel 1991; Traub et al. 2003). Additionally, several studies have addressed the interaction between gap-junctional strength and membrane properties in action potential propagation, failure and synchronization (Joyner et al. 1984; Keener 1990; Pfeuty et al. 2003). Processes of different dimensions are known to be electrically coupled to each other and the effectiveness of signal transmission between them may vary as a consequence of electrical load and coupling strength. For example, using modified cable theory, it has been shown that the diameter of gap-junctionally coupled cable-like processes, such as active cardiac myocytes, asymmetrically affects propagation velocity (Keener 1990). The role of process diameter on signal transmission in a single sealed-end cable has been examined with current and conductance inputs (Holmes 1989). However, the effect of diameter on signal transmission between processes coupled by gap junctions has not been studied.

We have previously shown that gap-junctional coupling can affect the measurements of ionic conductances and that these effects are sensitive to the location and strength of the gap junction (Rabbah et al. 2005). The results of that study implied that electrical signaling between neurons becomes more effective if the gap-junctional coupling strengthens or if the neurons become more electrotonically compact. Here we report that this intuition is not entirely correct. We observe a non-monotonic dependence of signal transfer between coupled passive cables as a function of cable diameter that is different in several respects to the single cable condition described by Holmes (1989). Although electrotonic access to a coupled cell improves with increased diameter, signal transfer may not. Signal transfer is maximized at an optimal cable diameter that depends differently on the cable properties and membrane properties of each cable and also sensitively depends on the coupling conductance. Thus, signal transfer actually deteriorates as the coupled cables become more electrotonically compact past a certain optimal diameter. In branched cables the optimal diameter depends on the specific properties of individual branches of the post-junctional cell. Therefore, functional compartmentalization may arise simply as a result of a difference in cable diameters in branches of coupled neuronal processes. We derive analytical expressions for signal transfer at steady state and examine the transient cases numerically. A comparison of the predicted optimal diameters with actual measurements of diameters of electrically coupled dendrites (Fukuda and Kosaka 2003) suggests that cable diameters may indeed be regulated to maximize neuronal signal transmission. Our results reveal a hitherto unknown phenomenon, namely the existence of an optimal diameter for gap-junctional signaling between cable-like structures such as neuronal processes and muscle tissues.

Methods

Analytical solutions

The steady-state equations for two cables coupled by non-rectifying gap junctions are derived from basic cable theory (Rall et al. 1995). The steady-state voltage (calculated as deviation from the resting potential) at any distance x along a uniform cylindrical cable of finite length len and length constant λ can be calculated as

| (1) |

where L = len / λ, X = x / λ, R∞ is the input resistance of a semi-infinite cable, RT is the terminating resistance at X = L and V0 is the voltage imposed at position 0 of the cable under voltage clamp conditions. To calculate the current flow between the finite cables electrically coupled at the end (X = L) we determine the voltage at the end of cable 1. For a single uncoupled cable, at X = L, Eq. 1 simplifies to

| (2) |

with and .

Rm, Ri and d have there usual meaning of specific membrane resistivity (Ωcm2), specific internal resistivity (Ωcm) and diameter, respectively.

End-to-end coupled cables

The terminating resistance of cable 1 (RT1), when coupled end-to-end to cable 2, is simply the sum of the gap junction resistance Rc and the input resistance of cable 2 (Rin_2) at the site of the gap junction. In general, for n end-to-end coupled cables, the terminating resistance of each cable is given by

| (3) |

with k = 1, ..., n-1. For the last (sealed) cable RTn = ∞. The input resistances Rin_k of all cables k = 1, ..., n-1 are given by the standard form of the input resistance of a cable with an arbitrary terminating resistance RTk:

| (4) |

R∞k and Lk are the input resistance of the semi-infinite cable, and electrotonic length of cable k, and Rin_n = R∞ coth Ln.

Combining Equations 1 and 3 we obtain an expression for the voltage at any position X along cable k:

| (5) |

For k = 1, Vk-1 = V0 is the clamped voltage.

The beginning of cable k+1 proximal to the gap junction behaves as a node in which the current flowing from the end of cable k through the gap junction is equal and opposite to the current flowing into cable k+1, i.e. Ik_c + Ik+1_0 = 0. This equation can be expanded to (Vk+1_0 – Vk_L)/Rc + Vk+1_0 / Rin_k+1 = 0. Solving for Vk+1_0, using Vk_X = Vk_L and X = Lk we obtain

| (6) |

Finally, the voltage at any electrotonic distance X along the sealed end-cable n is given by Equation 5 with RT = ∞:

| (7a) |

Equations 5-7 can be used to explicitly evaluate the voltages at any position along any cable. Thus, for 2 coupled cables,

| (7b) |

To obtain the cable diameter at which the value of V2_L is maximum (the optimal diameter), we calculated ∂V2_L / ∂d and found its positive root with the aid of the software Mathematica (Wolfram Research, Champaign, IL).

The voltage changes along the two coupled cables when the beginning of cable 1 was current or conductance clamped was calculated using equations 4-7. However, in current clamp V1_0 = Rin_1 Iext in Eq. 5, where Rin_1 is given by Eq. 4 and Iext is the applied constant current. In conductance clamp V1_0 = Esyn gsyn/(gsyn + 1 / Rin_1), where gsyn is the synaptic conductance and Esyn is the synaptic reversal potential.

Coupling along the middle region of semi-infinite cable pairs

To study the dependence of signal transmission between the equivalent of axons coupled by gap junctions at any position along their length as suggested by recent studies (Schmitz et al. 2001; Traub et al. 2003; Traub et al. 1999) we considered identical semi-infinite cables with a gap junction at a distance X = x/ λ from the clamped end of cable 1. Cable 1 is clamped at the beginning of the cable. Thus, its input resistance Rin_1X is given by Eq. 4 using the terminating resistance RT1_X given by

| (8) |

which corresponds to 2 parallel resistors, one with value R∞1 and the other with value Rc + Rin_2X. Rin_2X is the input resistance of cable 2 at the gap junction coupling position X and can be calculated as the equivalent resistance of two parallel resistors with values R∞ cothX for the sealed direction and R∞ for the infinite direction, thus Rin_2X = R∞ / (1 + tanhX). The voltage of cable 1 at the coupling position X (V1_X) is given by Eq. 2 with X substituting for L (with Rin_2X substituting for Rin_2 in Eq. 3). The voltage of cable 2 at the coupling position X is given by Eq. 6 with V1_X substituting for V1_L and Rin_2X for Rin_2. The voltage V2_0 at the sealed end of cable 2 is given by Eq. 7a with L2 = X: V2_0 = V2_X / coshX.

Two sealed cables coupled in the middle

The treatment for sealed-ended identical cables coupled at middle positions X is similar to the semi-infinite case describe above but the terminating resistance at position X is given by:

| (9) |

with input resistance Rin_2X given by:

| (10) |

Simulations

Three numerical models were used in this study.

Model 1

a spiking isopotential neuron was built using standard Hodgkin & Huxley equations (Hodgkin and Huxley 1952) coupled with a non-rectifying gap junction to the center of a passive cable 3100 μm long divided into 100μm long segments with Rm, Ri and Cm as above. Integrations of membrane and cable equations were performed using Network, a home-developed software running on the Linux platform, using a 4th order Runge-Kutta method with a time step of 10 μs (http://stg.rutgers.edu/software.htm; Rabbah et al. 2005).

Model 2

Two cells were coupled by a gap junction at the tips of their dendrites. Cell 1 was made of a spiking axon (6 compartments of length 100 μm), 10 μm in diameter, built using standard Hodgkin & Huxley equations (Hodgkin and Huxley 1952) connected to a passive soma with surface 400π μm2. Six passive dendrites of different diameters and length 600 μm (made of 6 compartments of length 100 μm each) emerge from the soma, and an action potential was elicited with a 10 msec, 1 nA pulse into the tip of the axon. The end of the dendrite of diameter 10 μm was coupled via a gap junction of Rc = 108 Ω to the tip of the passive dendrite of length 600 μm of a neuron with a passive soma of surface 400π μm2. Integrations of membrane and cable equations were performed using Network. In all passive compartments Rm = 40 kΩcm2, Ri = 100 Ωcm and Cm = 1 μF/cm2 to approximate data from hippocampal basket cells (Fukuda and Kosaka 2003).

Model 3

Each of two cables was modeled as cylinders of length 600 μm divided into 6 compartments of equal length. The membrane potential of compartment j (indexed from 0 to 5) of cable i is denoted by Vi_j. The two cables were gap-junctionally coupled at their ends, connecting segments 1_5 to 2_0. The compartments are built with specific membrane resistivity Rm = 40 kΩcm2, specific axial resistivity Ri = 60 Ωcm and specific membrane capacitance Cm = 10-6 F/cm2 (Hartline and Castelfranco 2003). In these simulations V1_0 was voltage clamped to produce a sinusoidal change in voltage, V1_0(t)=A sin(ωt), where A is a scaling factor.

Results

An optimal diameter exists when two cables are coupled by gap junctions

Using basic equations of cable theory, it can be readily demonstrated that an elongated process becomes more electrotonically compact if its diameter increases. This is a consequence of the fact that the length constant of a uniform cable is proportional to the square root of its diameter. Therefore, the larger the diameter, the larger the length constant λ and the smaller the electrotonic length (len/λ) of the cable. Consequently, if one end of a finite sealed-end cable is voltage clamped (at V1_0 ≠ Vrest), the voltage attenuation along the cable is less if the cable diameter is larger, and thus the voltage at the distal end of the cable is closer to V1_0.

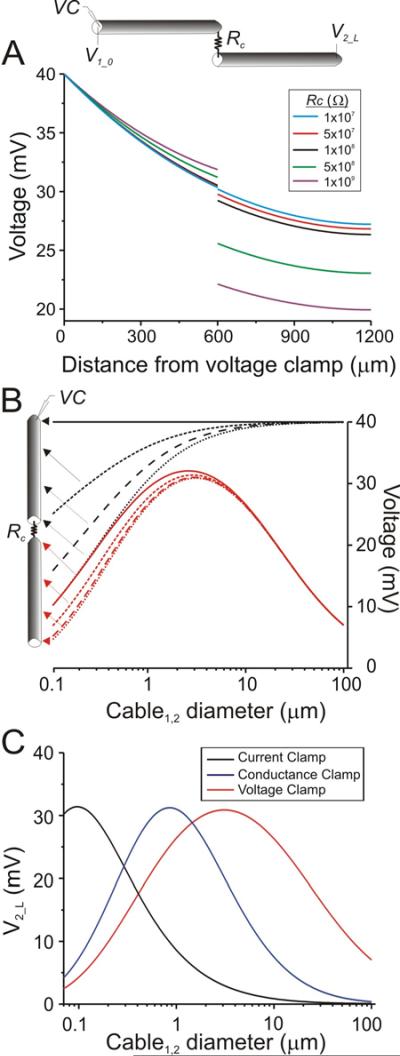

If, additionally, this cable is coupled at its distal end via gap junctions to a second cable, there will be a voltage drop across the gap junction and the voltage attenuation will continue along the second cable. This is demonstrated in Fig. 1A by plotting the voltages along two cables, each of length len = 600 μm, coupled at the end with a gap junction of resistance Rc, when V1_0 is voltage clamped at 40 mV. These traces were calculated using Equations 1 and 5 for cable 1. For cable 2, Equation 6 was used to determine V2_0, Equation 7b to determine V2_L, and Equation 1 with V0 = V2_0 to determine V2_X. As the coupling resistance Rc is decreased, the voltage drop across the gap junction becomes less pronounced and the two coupled cables resemble more and more a single cable with length = len1 + len2 (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Steady state behavior of two cables coupled by a gap junction. Voltages along two electrically coupled cables, both with Rm = 40 kΩcm2, Ri = 60 Ωcm, len = 600 μm and connected at one end by a gap junction of resistance Rc. In voltage clamp (VC), the beginning of cable 1 (V1_0) was set to 40 mV. A. Top: Schematic diagram of the connected cables. Bottom: Voltage versus position along the two cables (V1_0 =40 mV in VC). Both cables have diameter 1 μm. B. The voltage at each position (indicated by arrows on schematic diagram) is shown as a function of cable diameter. The diameters of both cables were equal and varied simultaneously. V1_0 =40 mV in VC. Rc = 108 Ω. C. Comparison between current clamp, conductance clamp and voltage clamp conditions as measured at the end of cable 2 (V2_L) as a function of diameter. Red trace is the same as in B. Black trace was obtained by injecting 10nA at the beginning of cable 1. Blue trace was obtained using a synaptic current input at the beginning of cable 1 with gsyn=1.5nS and Esyn at 70 mV above Vrest.

Figure 1B shows the voltages along the two cables as the diameters of both cables are simultaneously varied. The top four traces correspond to voltages at four equidistant positions along cable 1 and the lower four traces to voltages at equidistant positions along cable 2 (as indicated by arrows in the schematic diagram). As expected, we found that when the beginning of cable 1 was voltage clamped, the voltage attenuation along this cable monotonically decreased as its diameter increased. This was not the case for voltages along cable 2. Although for any fixed diameter there was voltage attenuation along cable 2 (Fig. 1A), as diameter was increased, at any given position along cable 2 the voltage first increased and then decreased (Fig. 1B, bottom 4 traces). Thus, for each position along cable 2, there was a cable diameter at which the voltage attenuation was minimal. We refer to this value as the “optimal diameter” and to the voltage vs. diameter graph as a “diameter tuning curve.”

A qualitatively similar result was obtained in current-clamp conditions with a constant current applied to the beginning of cable 1. However, the optimal diameter obtained in current clamp was more than one order of magnitude smaller than that in voltage clamp (Fig. 1C). An optimal diameter was also observed if a fixed conductance —the equivalent of a synaptic current input isyn=gsyn (V–Esyn)— was applied to the beginning of cable 1 (Fig. 1C). In this study we will only analyze the case when the beginning of cable 1 is voltage clamped. The other cases can be treated in a similar fashion.

To understand how the optimal diameter emerges, we used analytical expressions for the steady-state voltages along two uniform cables of finite length, coupled at the end with a gap junction (Methods, Equations 1-7). We will show that the optimal diameter depends on the gap junction resistance as well as the membrane properties of both cables.

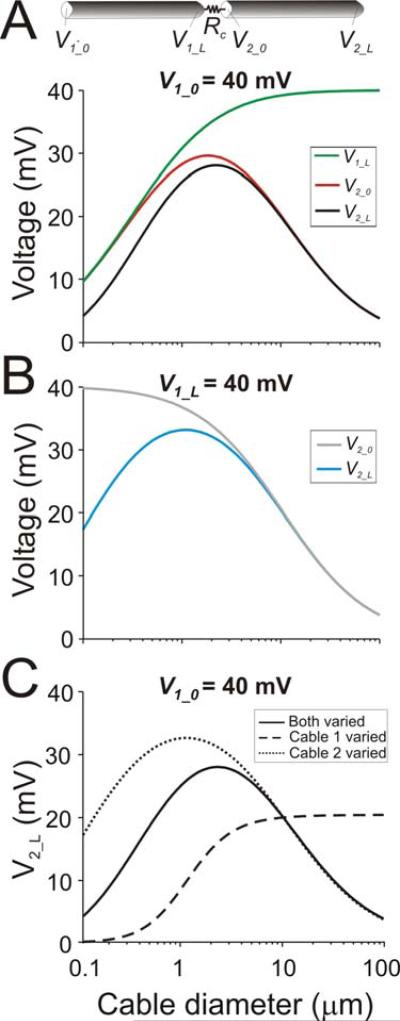

Using Equations 5 and 6 we compared the voltages at the two sides of the gap junction (V1_L and V2_0) when the proximal end of cable 1 (V1_0) was voltage clamped (compare green and red traces in Fig. 2A). As expected, V1_L (green trace) approached the value of V1_0 (= 40 mV) as the cable diameters (d) increased. Within a range of relatively small d values, the voltages across the gap junction were close in value and V2_0 (red trace) tracked V1_L. However, as d increased further, V1_L approached a plateau but V2_0 began to decrease. The rise and fall of V2_0 as a function of d can be readily explained using Equation 6 and the dependence of Rin_2 on diameter. At small d values, the input resistance of cable 2 (Rin_2) is relatively large. In fact, in this range of d, Rin_2 is much larger than the gap junction resistance Rc and thus, to a first approximation, Rc can be ignored in the denominator of Equation 6 and V2_0 tracks V1_L, which is increasing. However, Rin_2 decreases as d increases (Rin_2 = R∞2 coth coth()) and, for large d, Rin_2 becomes much smaller than Rc. Thus, for large d, the value of V2_0 decreases with Rin_2 even as the value of V1_L continues to increase and approaches a constant (Equation 6). In effect, Rc acts as a current limiter: as its diameter increases, cable 2 becomes more “leaky” and the Rc-limited current flowing into cable 2 results in a progressively lower current density and more attenuated voltage change along cable 2. Note that the existence of the optimal diameter is not limited to V2_0 but an optimal diameter exists for all positions along cable 2 as seen in the voltage at the distal end of cable 2 from the gap junction (V2_L, black trace in Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

Analytical solutions of diameter-dependence of voltage spread. Schematic diagram shows the two identical cables (Rm = 40 kΩcm2, Ri = 60 Ωcm, len = 600 μm) coupled at one end by a gap junction of resistance Rc = 2×108 Ω. A. Cable 1 is voltage clamped to 40 mV at the end opposite to the gap junction (V1_0). Voltage changes at positions V1_L, V2_0 and V2_L as a function of cable diameter were determined analytically using Equations 5-7 (see Methods). The diameters of both cables were varied simultaneously. B. Cable 1 is voltage clamped to 40 mV at the end adjacent to the gap junction (V1_L). Voltage changes at positions V2_0 and V2_L as a function of cable diameter were determined analytically using Equations 5-7 (see Methods). The diameters of both cables were varied simultaneously. C. Effects of changing the diameter of each cable independently on voltage at the distal end of cable 2 (V2_L). Cable 1 is voltage clamped to 40 mV at V1_0-. Diameter of the fixed cable is 10 μm. Also shown, for comparison, is the effect of simultaneous variation of the diameters of both cables (solid trace; same as black trace in A).

This current-limiting effect of the gap junction can also be demonstrated by voltage clamping cable 1 at its distal end, next to the gap junction (V1_L) and plotting V2_0 as a function of diameter (Fig. 2B, grey trace). The value of V2_0 is close to V1_L (= 40 mV) for small d and drops as d increases but, in this case, there is no optimal diameter for V2_0. Note, however, that all portions of cable 2 except the point immediately adjacent to the gap junction (e.g. V2_L, blue trace in Fig. 2B) show an optimal diameter. This is due to the fact that the term 1/cosh(L2) in Equation 7b grows monotonically as the diameter of cable 2 increases while V2_0 monotonically decreases, independent of the voltage at V1_L. The product of these two terms (Equation 7b) generates the peak voltage at an optimal diameter.

Note that the drop in V2_L is primarily due to the fact that Rin_2 decreases as the diameter of cable 2 increases. Thus, when the diameter changes are restricted only to cable 1 (Fig. 2C, dashed trace) no optimal diameter is observed. However, if only the diameter of cable 2 is modified an optimal diameter appears (Fig. 2C, dotted trace). The optimal diameter occurs at a larger value when the diameters of both cables are simultaneously modified (Fig. 2C, solid trace) because at small diameters, V1_L is significantly more attenuated compared to V1_L when d1 is fixed, effectively “pushing” the left side of the diameter tuning curve down and the optimal diameter to the right.

Dependence of optimal diameter on membrane properties

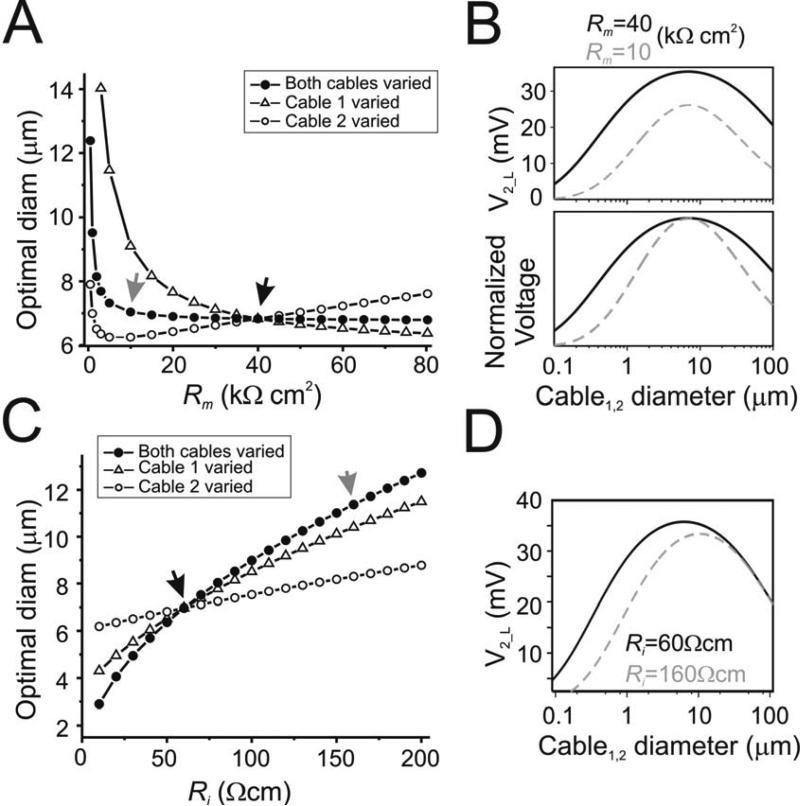

The steady-state voltage profile along a cable depends on the specific membrane resistance Rm, specific axial resistance Ri, length and diameter. Figure 3 shows the effects of Rm and Ri on the optimal diameter of two cables coupled with Rc = 2×108 Ω. The dependence of optimal diameter on Rm is most pronounced when only Rm1 is increased (Fig. 3A, open triangles), showing an initially rapid, followed by a more gradual, decrease. The effect of the Rm of cable 2 on optimal diameter also shows an initially rapid (but less pronounced) decrease as Rm2 increases up to approximately 5 kΩcm2. At this point, and in contrast to what is seen when Rm1 is varied, the optimal diameter starts to increase linearly with Rm2 (open circles). The combined effect of simultaneously changing Rm in both cables is a rapid decrease of the optimal diameter as Rm increases up to approximately 10 kΩcm2 and an apparent independence of the optimal diameter above this point (filled circles). Increases in voltage attenuation due to decreases in Rm are accompanied by an increased sharpness in the diameter tuning curve (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Effect of membrane properties on optimal diameter. Analytical results calculated for two cables of equal length (600 μm) connected by a gap junction of Rc = 2×108 Ω. Beginning of cable 1 was clamped to 40 mV and diameters of both cables were varied simultaneously. A. Optimal diameter for different Rm values of only cable 1 (open triangles; Rm2 = 40 kΩcm ), only cable 2 (open circles; Rm1 = 40 kΩcm2), or both cables (filled circles). Ri = 60 Ωcm. B. Steady state diameter tuning curve measured at end of cable 2 (both cable diameters varied simultaneously) for Rm values indicated by arrows in A (40 and 10 kΩcm2) to show effect on attenuation (top panel) and sharpness (bottom panel, voltages normalized to curve maxima for enhanced visibility) of tuning curve. C. Optimal diameter for different Ri values of only cable 1 (open triangles; Ri2 = 60 Ωcm), only cable 2 (open circles; Ri1 = 60 Ωcm), or both cables (filled circles). Rm = 40 kΩcm2. D. Steady state diameter tuning curve measured at end of cable 2 (both cable diameters varied simultaneously) for Ri values indicated by arrows in C (60 and 160 Ωcm) to show effect on attenuation and sharpness of tuning curve.

The optimal diameter along cable 2 can be readily derived for the signal at the distal end (V2_L) by evaluating ∂V2_L / ∂d = 0 using Equation 7b. Assuming that the two cables are identical and co-vary in diameter, this equation can be simplified to obtain

| (11) |

Equation 11 can be used to approximate the dependence of the optimal diameter on the membrane parameters, Rm, Ri and len. The left-hand side of Equation 11, i.e. tanh 2L, is bound between 0 and 1. The right-hand side has a vertical asymptote when the denominator is zero. At low values of d this vertical asymptote occurs close to the point of intersection with tanh 2L; i.e., the value of d at which 3Rc – 4R∞L = 0 (say d̃) is near the optimal diameter d*. Thus, solving for the value of d at the vertical asymptote provides a good approximation of the dependencies of d* on membrane parameters. This value, which is valid only for relatively large values of Rm (in our case > ~10 kΩcm2), is given by

| (12) |

Note that d̃ is independent of Rm, reflecting the independence of the optimal diameter from variations of Rm in both cables above ~10 kΩcm2 (Fig. 3A, filled circles).

The optimal diameter changes in a monotonic fashion whether Ri1 or Ri2 is modified, with the optimal diameter increasing as Ri increases. As in the case of Rm variations, the effect is more pronounced when Ri1 (Fig. 3C, open triangles) is modified than Ri2 (open circles). This effect is even more pronounced when Ri in both cables are simultaneously changed (filled circles). Equation 12 indeed shows that, for two identical cables, the optimal diameter variations are proportional to . The effect of Ri on optimal diameter is somewhat comparable to the effect of Rm in that changes that increase voltage attenuation along either of the two cables (namely by reduction of Rm below 10 kΩcm2 or increase of Ri) increase the optimal diameter value. As in the case of Rm changes, increases in voltage attenuation due to changes in Ri are accompanied by an increased sharpness of the diameter tuning curve (Fig. 3D).

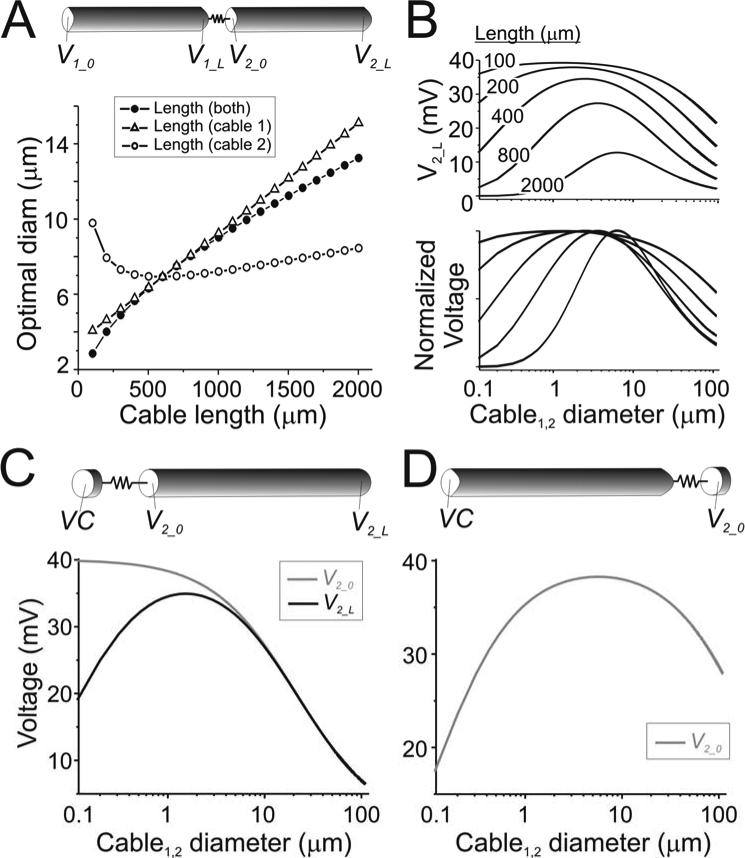

Changes in cable length have a similar effect as changes that increase voltage attenuation (i.e. decreased Rm or increased Ri). Figure 4A shows that increasing the length of cable 1 (open triangles) leads to an almost linear increase in optimal diameter. Increasing the length of cable 2 leads to an initial reduction of optimal diameter at low length values and then an almost linear increase for higher values (Fig. 4A, open circles). When both cable lengths are increased simultaneously, the optimal diameter increases monotonically in a manner similar to how optimal diameter varies with Ri when both cables are varied simultaneously (Fig. 4A, filled circles). Equation 12 shows that, for two identical cables, the optimal diameter changes proportional to . This increase in optimal diameter is accompanied by progressive signal attenuation (Fig. 4B, top panel). As with changes in Rm or Ri, changes in cable length that lead to the attenuation of voltage result in a sharpening of the diameter tuning curve accompanied by a marked shift in the optimal diameter to larger values (Fig. 4B, bottom panel). At the limit when either cable is so short (length = 20 μm) as to be nearly isopotential, an optimal diameter still exists, albeit of different values (Fig. 4C and D). Note that when cable 1 is isopotential, V2_0 no longer shows an optimal diameter but the distal points along cable 2 do (Fig. 4C). When cable 2 is isopotential it nonetheless shows an optimal diameter (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4.

Effect of cable length on optimal diameter. Analytical results were calculated for two cables of varying lengths connected by a gap junction of Rc = 2×107 Ω. Beginning of cable 1 was clamped to 40 mV and diameters of both cables were varied simultaneously. A. Optimal diameter for varying lengths of only cable 1 (open triangles; len2 = 600 μm), only cable 2 (open circles; len1 = 600 μm), or both cables (filled circles). Ri = 60 Ωcm; Rm = 40 kΩcm2. B. Steady state diameter tuning curves at V2_L for cables of different length (both cable diameters varied simultaneously) to show the effect of length on attenuation (top panel; length indicated on traces), and sharpness of tuning curve and shifting of the optimal diameter (lower panel; voltages normalized to maxima for enhanced visibility). C. Limit case when cable 1 is isopotential (len1 = 20 μm; len2 = 600 μm; schematic diagram) showing the diameter tuning curves for V2_0 (grey trace) and V2_L (black trace). D. Limit case when cable 2 is isopotential (len1 = 600 μm; len2 = 20 μm; schematic diagram) showing the diameter tuning curve of cable 2.

Equation 12 demonstrates a simple relationship of the optimal diameter to Ri and cable length len and independence from Rm above a certain range of values, only when both coupled cables are identical. When these parameters are different for each of the two coupled cables these relationships no longer hold and the determination of an optimal diameters for signal transfer become significantly more complex (Figs. 3 and 4, open symbols).

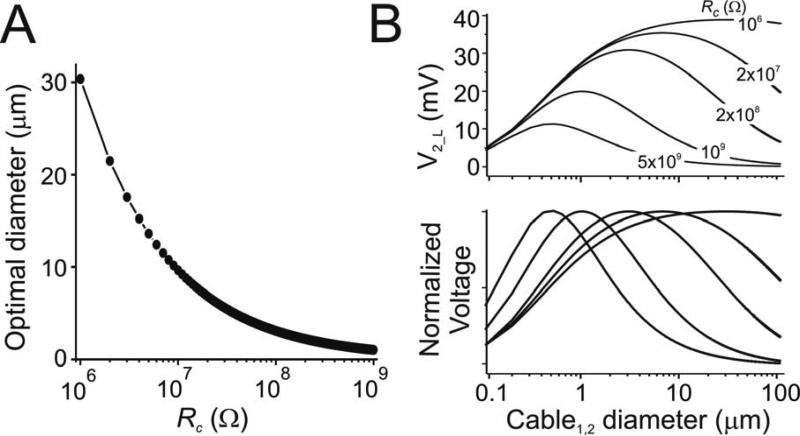

Dependence of optimal diameter on gap junction resistance

Gap junction resistance sensitively determines optimal diameter for signal transfer between coupled cables. As gap junction resistance increases, the optimal diameter sharply decreases (Fig. 5A). Notice that a drop of approximately 70% occurs between gap junction conductances of 106 to 107 Ω (Fig. 5A). However, while at Rc = 109 Ω the optimal diameter is reduced by over one order of magnitude compared with Rc = 106 Ω (Fig. 5A), the amplitude of the signal is attenuated only approximately 50% (Fig. 5B, top panel). As in the case of Rm, Ri and cable length, Eq. 12 confirms that optimal diameter is proportional to when both cables are identical (Fig. 5A). As describe before for the effects of Rm, Ri and length on optimal diameter, attenuation of the signal is accompanied by an increased sharpness in the diameter tuning curve (Fig. 5B, bottom panel).

Figure 5.

Effect of gap junction resistance on optimal diameter. Analytical results for two cables connected by a gap junction of varying resistance Rc. For both cables Rm = 40 kΩcm2, Ri = 60 Ωcm, len = 600 μm. Beginning of cable 1 is clamped to 40 mV and diameters of both cables were varied simultaneously. A. Optimal diameter as a function of Rc. B. Diameter tuning curve at end of cable 2 (V2_L) for five different values of Rc to show the effect of Rc on attenuation (top panel), and the sharpness of the tuning curve and shifting of the optimal diameter (lower panel; voltages normalized to maxima for enhanced visibility).

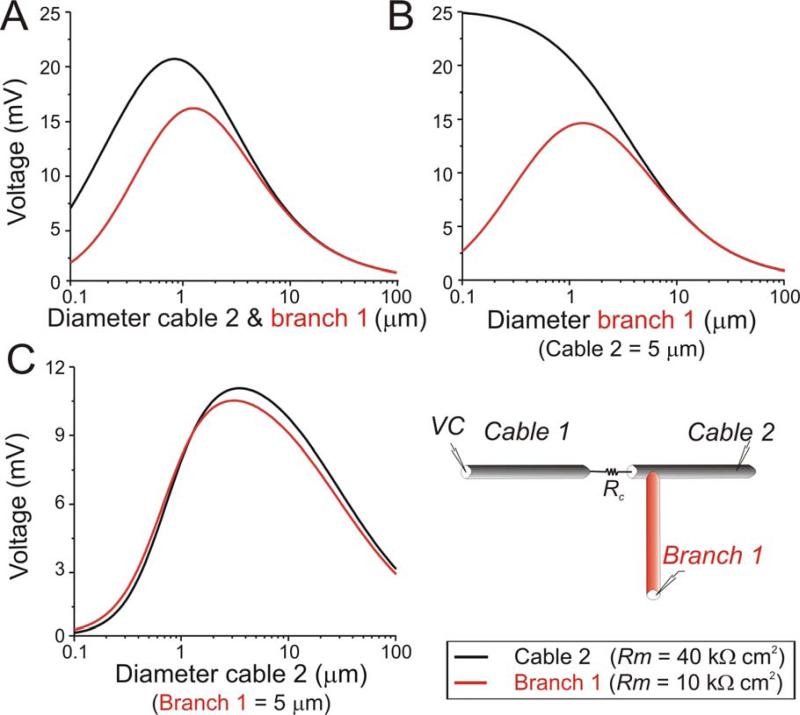

Effect of branching on optimal diameter

The dependence of the optimal diameter on membrane properties suggests that different branches in a dendritic tree, having different membrane properties, may also express different optimal diameters. Indeed, Fig. 6A shows that dendrites with different membrane resistances but otherwise identical properties display different optimal diameters. When the diameters of both the mother cable 2 and its daughter branch (Branch 1) are varied simultaneously the cable with lower input resistance (Fig. 6A, red trace) shows a larger optimal diameter and a sharper but more attenuated diameter tuning curve. This confirms the rule of thumb mentioned before: properties that increase voltage attenuation, increase the sharpness of the diameter tuning curve. This effect is local because diameter changes in a daughter branch produce an optimal diameter only in that branch (Fig. 6B, red trace). Diameter changes in a mother dendrite (Cable 2) will produce almost the same optimal diameter in that dendrite and its daughter branches, with exact values depending on the specific membrane properties of the daughter branch (Fig. 6C; note that the post-junctional segment closest to the gap junction is part of the mother branch - see schematic diagram).

Figure 6.

Effect of cable branching on optimal diameter. Analytical results were calculated for two cables (cables 1 and 2) connected by a gap junction of resistance Rc = 2×108 Ω (Rm = 40 kΩcm2, Ri = 60 Ωcm, len1,2 = 600 μm). A daughter branch 1 emerges from cable 2 at a distance of 200 μm from the gap junction (schematic diagram). Rm of branch 1 is 10 kΩcm2. Otherwise, properties are the same as those of cable 2. The beginning of cable 1 was voltage clamped at 40 mV and its properties, including its diameter (d1 = 5 μm), remained fixed. The voltage changes at the tips of both cable 2 (black trace) and branch 1 (red trace) are plotted as a function of diameter. A. The diameters of both cable 2 and branch 1 are varied simultaneously. B. The diameter of cable 2 is fixed at 5 μm and the diameter of branch 1 is varied. C. The diameter of the branch 1 is fixed at 5 μm and the diameter of cable 2 is varied.

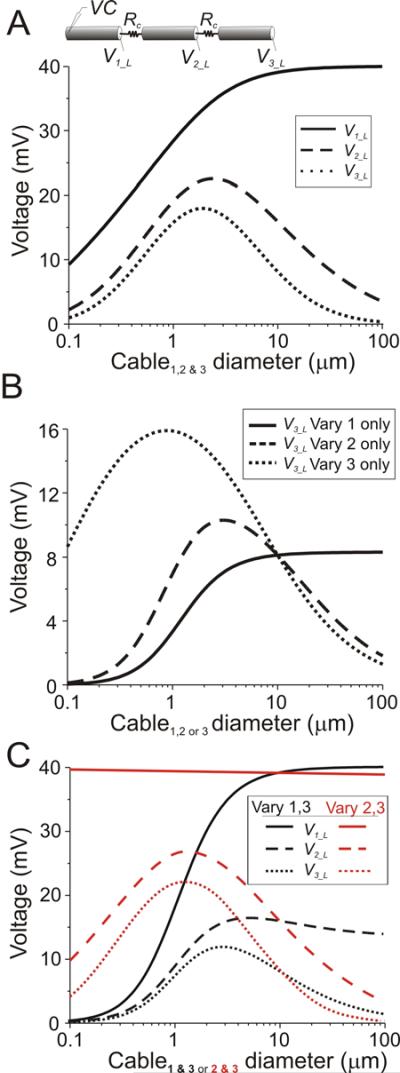

Series of cables connected end-to-end

Cables of similar properties connected end-to-end in series (see diagram in Fig. 7A) correspond to a condition analogous to that found in some biological tissues, most notably cardiac muscle (Joyner et al. 1984) and some striated muscle fibers (e.g in Drosophila; G. Davis, personal communication). Figure 7A shows the response, measured at the distal ends (Vi_L, i = 1, 2, 3), of three identical cables connected end-to-end when the proximal end of cable 1 (V1_0) is voltage clamped to 40 mV (see schematic diagram). As in the case of two cables connected in a similar manner, the end of cable 2 shows a clear optimal diameter for signal transfer. However, in contrast with the two-cable case, the three-cable case shows a slightly smaller optimal diameter when measured at the end of cable 2 (2.5 μm compared to slightly above 3 μm in the 2-cable case; compare dashed trace of Fig. 7A with lowermost trace in Fig. 1B). Furthermore, the end of cable 3 shows a still lower optimal diameter value, a sharper tuning curve and a more attenuated amplitude at all cable diameter values (Fig. 7A, bottom trace). Figure 7B shows that variation in diameter of the individual cables has very different effects on both the attenuation of signals and the optimal diameter value. As in the two-cable case, varying the diameter of cable 1 alone affects exclusively the attenuation of the signal measured at the end of the last cable and there is no optimal diameter (Fig. 7B, solid trace). When only cable 2 diameter is varied, a sharp peak (optimal diameter) appears in the cable diameter tuning curve (Fig. 7B, dashed trace) while variations in cable 3 diameter alone produce a less attenuated and broader cable diameter tuning curve with a significantly lower optimal diameter value (Fig. 7B, dotted trace). A similar result is observed if the diameters of all but one of the three cables are varied simultaneously: as the cables whose diameters are varied are placed farther away, the optimal diameters values become shorter and the amplitudes less attenuated (Fig. 7C). In other words, middle cable diameters in end-to-end connection configuration have a stronger effect on signal attenuation but a weaker effect on tuning of the diameter tuning curve.

Figure 7.

Steady state behavior of three cables electrically coupled in series. Voltages measured at the distal end of each coupled cable (V1_L, V2_L, V3_L). All cables were built with Rm = 40 kΩcm2, Ri = 60 Ωcm, len = 600 μm and connected at one end by a gap junction of resistance Rc = 108 Ω. The voltage at the beginning of cable 1 was clamped to 40 mV. A. Top: Schematic diagram of connectivity. Bottom: V1_L (solid line), V2_L (dashed line) and V3_L (dotted line) shown as a function of cable diameter when the diameters of all 3 cables were varied simultaneously. B. V3_L shown as a function of cable diameter when the diameters of only cable 1 (solid trace), only cable 2 (dashed trace) or only cable 3 (dotted trace) were varied. C. V1_L, V2_L and V3_L shown when the diameter of both cables 1 and 3 (black traces) or both cables 2 and 3 (red traces) were varied. In B and C, the fixed-diameter cables had diameter = 10 μm.

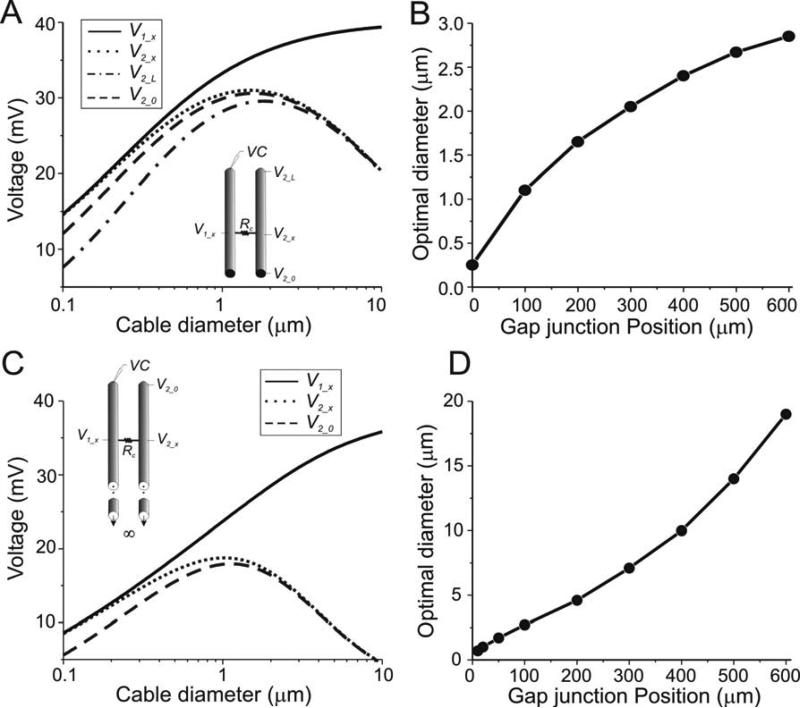

Cables connected in a middle position

Dendro-dendritic gap junctions are common in the central nervous system (Fukuda and Kosaka 2003; Matsumoto et al. 1988; Sotelo et al. 1986). Also, recent studies have proposed that axo-axonic gap junctions are present between hippocampal pyramidal neurons and account for the generation of spikelets (Schmitz et al. 2001; Traub et al. 2003; Traub et al. 1999). The results of the current study suggest that transmission of signals between two axons, between axons and other neuronal processes or between dendrites depends on the diameter of the processes involved. We addressed this hypothesis by examining the effects of gap-junctional coupling between two cables at intermediate positions along the cable (see schematic diagrams in Fig. 8). We considered two different configurations: coupling between sealed cables (Fig. 8A,B) and coupling between semi-infinite cables (Fig. 8C,D; see Methods). As before, in both cases we looked at the steady state voltages along cable 2 when the beginning of cable 1 was voltage clamped. Under these conditions our results qualitatively correspond to those observed for endto-end coupled cables: in both cases an optimal diameter for signal transmission is present at all positions along cable 2 (e.g., dotted and dashed traces in Fig. 8A for the sealed-end case, and Fig. 8C for the semi-infinite case), while no optimal diameter is observed along cable 1 (black traces in Figs. 8A,C). The main differences between these two cases are that the sealed-end cable shows less signal attenuation across the gap junction and larger optimal diameter values than the semi-infinite cables. In both cases, the optimal diameter is dependent on the gap junction position. As the gap junction is moved farther away from the sealed end, both the optimal diameter and signal attenuation increase (Fig. 8B, D).

Figure 8.

Steady state behavior of two cables coupled by a gap junction in a middle position. Rm = 40 kΩcm2, Ri = 60 Ωcm, Rc = 2×108 Ω. Both cables are identical and coupling is symmetrically placed. The voltage of the beginning of cable 1 was clamped to 40 mV. Position x corresponds to the distance from the point of voltage clamp to the gap junction location. The diameters of both cables were identical and varied simultaneously. A. Sealed-end cables. The voltages at the pre- and postsynaptic side of the gap junction (V1_x and V2_x) as well as both ends of the unclamped cable (V2_0 and V2_L) are shown as a function of cable diameter. Schematic diagram indicates geometric configuration. len = 600μm. x = 400 μm. B. Optimal diameter (for V2_x) for signal transmission between sealed cables as a function of gap junction position. C. Semi-infinite cables. The voltages at the pre- and postsynaptic sides of the gap junction (V1_x and V2_x) as well as at the sealed end of the unclamped cable (V2_0) are shown as a function of cable diameter. Schematic diagram indicates geometric configuration. x = 400 μm. D. Optimal diameter (for V2_x) for signal transmission between semi-infinite cables as a function of gap junction position.

Gap junction-mediated coupling potentials

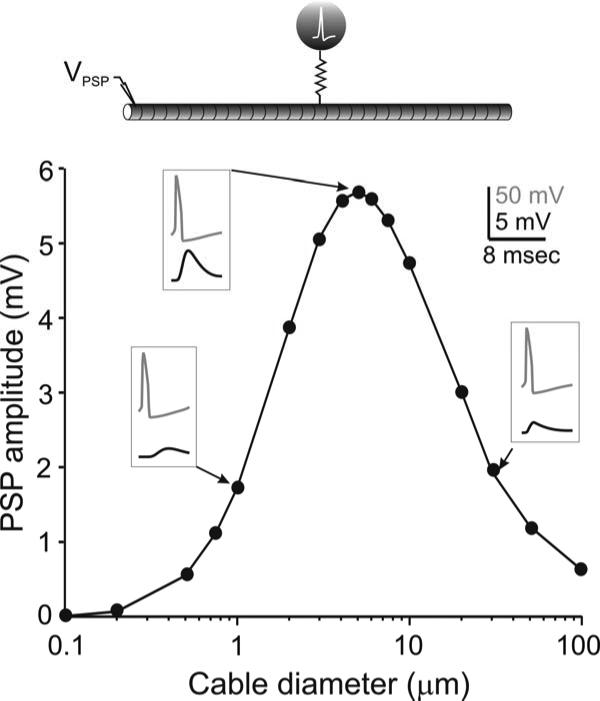

To further examine the effects of diameter on a signal transmission analogous to axoaxonal coupling, we coupled an action potential-generating single-compartment model neuron to the center of a long multi-compartment cable (Model 1 in Methods; Fig. 9, schematic diagram). We found that the coupling potential produced by the action potential in the coupled cable shows a maximal amplitude at a unique cable diameter, in this case at approximately 5 μm (Fig. 9, top inset). The coupling potential amplitude was diminished if the axon diameter was different. One interesting consequence of the optimal diameter is that, although the amplitude of the PSP coupling potential produced at a small diameter (e.g. 1 μm, leftmost inset in Fig. 9) may be almost identical to the amplitude at a diameter higher than the optimal value (e.g. 30 μm, rightmost inset in Fig. 9), the time course of the these coupling potentials varies greatly owing to the different time constants of the membrane at these different diameters.

Figure 9.

Effect of cable diameter on action potential propagation across gap junctions. Top diagram. A single-compartment neuron (Methods) capable of producing an action potential is coupled via a gap junction of resistance Rc = 2×107 Ω to the center of a 31-compartment sealed passive cable of length 3100 μm, Rm = 40 kΩcm2, Ri = 60 Ωcm, Cm = 1 μF/cm2. A PSP is measured at one end of the cable for different diameters. Insets show the action potential in the active cell (grey, top trace) and the PSP at one end of the cable (black, bottom trace) for three different cable diameters.

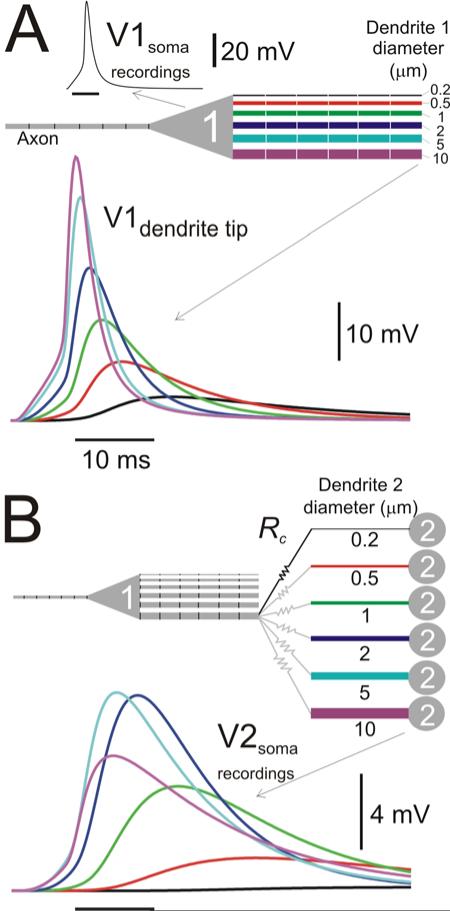

The functional implications of the existence of an optimal diameter for signal transmission across a gap junction are further illustrated in the multi-compartment model of dendro-dendritic propagation of an action potential (Model 2 in Methods; Fig. 10). Figure 10A shows an action potential propagating from the axon, through a passive soma and into the tips of passive, uncoupled dendrites of different diameters. The membrane potential amplitude at the tip of the dendrites increased with the diameter of the dendrite and no optimal diameter was observed. In contrast, when the tip of one of the dendrites was electrically coupled to the tips of the dendrite of a second (ball-and-stick) passive neuron, the resulting electrical coupling potential recorded at the soma of cell 2 had maximal amplitude for the dendrite of diameter 5 μm (Fig. 10B). The results shown in Fig. 10B imply, for example, that only the post-junctional neurons with dendrite diameters of 2 and 5 μm would produce action potentials in response to the electrical coupling potential, if the spike threshold is ~8 mV above the resting potential.

Figure 10.

Effect of cable diameter on action potential propagation through passive dendrites and across a gap junction. A. The membrane potentials of an invading action potential in the soma (V1soma) and at the tips of 6 dendrites (V1dendrite tip) of varying diameters are shown. The neuron was built with a 6-compartment spiking axon, a passive soma and 6 passive, 600 μm long dendrites (made of 6 compartments 100 μm long each) , Rm = 40 kΩcm2, Ri = 100 Ωcm and Cm = 1 μF/cm2 (schematic diagram). B. The distal tip of the 10 μm diameter dendrite of the same neuron as in A (Cell 1) was coupled to the tip of the “dendrite” of a ball-and-stick passive neuron (Cell 2; schematic diagram). The diameter of the dendrite of Cell 2 was varied and the PSP recorded at the soma of Cell 2. Cell 1 was only coupled to one Cell 2 in each simulation run (black resistor symbols in schematic diagram) and the diameter of Cell 2 was changed in each run (grey resistor symbols). Rc = 108 Ω. Horizontal scale bars are 10 ms long.

Effects of signal frequency on optimal diameter

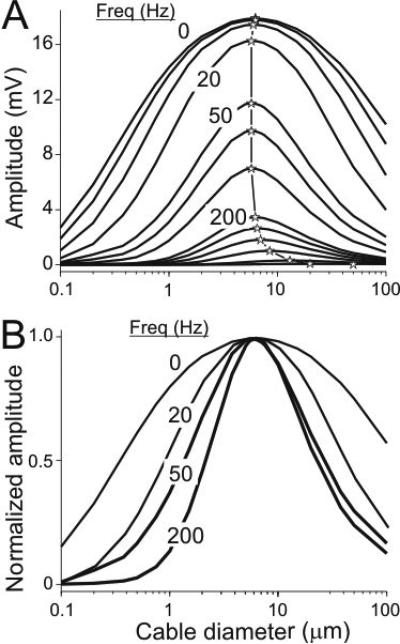

Although we do not present here the analytical solutions to the transient (non steady-state) case, the behavior of two end-to-end coupled cables in response to a sinusoidal change in voltage at the beginning of cable 1 can be intuitively understood in a way similar to the effects of Rm on voltage attenuation and the presence of an optimal diameter for signal transfer along coupled cables. We used numerical simulations of compartmentalized cables (Model 3 in Methods) to show that as the frequency of the input signal (V1_0) increases and the impedances of the cables decrease, the amplitude of the output signal decreases (V2_L; Fig. 11A). At the same time, the optimal diameter gradually increases (stars and vertical traces) very much like the optimal diameter increases as Rm (of both cables simultaneously) decreases in the steady state case (Fig. 3A, solid symbols). The increased signal attenuation at high frequencies is also accompanied by a sharper diameter tuning curve (Fig.11B) similar to that observed in the steady state case (Fig. 3B).

Figure 11.

Effect of input frequency on optimal diameter. Two cables of length = 600 μm (6 compartments of equal length each), Rm = 40 kΩcm2, Ri = 60 Ωcm, were coupled with a gap junction of resistance Rc = 2×107 Ω. Sinusoidal voltage clamp signals of amplitude 20 mV with different frequencies were applied to the first compartment of cable 1 and the diameters of both cables were varied simultaneously. A. Graph shows diameter tuning curves at the distal end of cable 2. Range of frequencies from top to bottom: 0-1000 Hz. Some frequencies are indicated for reference. The stars mark the optimal diameter at each frequency. The lines connecting the stars are added for increased visibility. B. Diameter tuning curves for 0 Hz (pulse), 20, 50 and 200 Hz, normalized to their peak values, showing the increased sharpness of the curves, but little change in optimal diameter, with increasing input frequency.

Discussion

Recent experimental results have shown gap junctions to be much more prevalent in the nervous system than previously known. Few pharmacological agents affect gap junctions specifically and direct experimental measurement or manipulation of electrical coupling is notoriously difficult (for a review see Connors and Long 2004). Consequently, theoretical studies of electrical coupling are necessary to understand the network consequences of its interactions with the membrane properties of the coupled cells. We examined the interaction between electrical coupling and cable properties of coupled processes on signal transfer attenuation. We show that two gap-junctionally coupled passive cables will produce maximal signal transfer (coupling potential) at a certain “optimal” diameter. Such an optimal diameter exists for both steady state signals and action potentials or periodic signals and occurs at similar values for frequencies up to at least 200 Hz. This optimal signal transfer may be potentially important in the operation of neuronal systems that involve gap junctional communication, where coupling potentials of optimal amplitude may result in activating regenerative events such as action potentials, plateau potentials and voltage-dependent membrane potential oscillations (Fig.10).

Comparison with optimal diameter of a single cable in current clamp

A previous study has shown that a single cable has an optimal diameter at the distal end when a constant current or conductance is injected in the proximal end (Holmes 1989). This single-cable optimal diameter is determined exclusively by the electrotonic length L of the cable, is independent of the input resistance and the terminating resistance and, furthermore, it disappears when the cable is voltage clamped. The optimal diameter of two coupled cables, described in this study, is qualitatively distinct from that of the single cable described by Holmes (1989) and cannot be reduced to that case. In particular, the optimal diameter in our study is dependent on the input resistances and length constants of the coupled cables as well as the gap junction resistance (Eq. 11) and, furthermore, it occurs in voltage clamp (this study) as well as in current clamp conditions and conductance clamp conditions (Fig. 1C). Additionally, the current clamp optimal diameter described by Holmes (1989) occurs at values an order of magnitude smaller than the optimal diameter of two gap-junctionally coupled cables. Specific membrane resistance (Rm) values measured in vertebrate neurons using the whole cell patch clamp technique are 10-70 kΩcm2 (see references in Coleman and Miller 1989). For invertebrates, the values are commonly lower (Rall 1977) but can also be in the higher range (Hartline and Castelfranco 2003). For such Rm values, the current-clamp optimal diameter in single cables are below physiologically realistic levels (<0.1 μm; Berthold 1978; Mikelberg et al. 1989) but the optimal diameters for gap-junctionally coupled cables fall within the physiological range (0.1-10μm; Figs. 3-5) in either current, conductance or voltage clamp conditions (Fig. 1C).

Relationship between optimal diameter and cable properties

It may seem that the optimal diameter arises because, with increasing diameters there is better electrotonic access to the distal points but that larger diameters put a larger load on the current source. These two opposing effects would thus produce optimality. However, while this intuition is correct for the current clamp single cable case, it is insufficient in general because these opposing effects also occur in a single voltage clamped cable without producing an optimal diameter. In the case of two coupled cables, the existence of the optimal diameter depends crucially on the limiting effect of the gap junction on current flow. The gap junction acts as a voltage divider that limits the current flow into the second coupled cable. Therefore, while the signal at the end of cable 1 monotonically approaches the voltage of the proximal end, the current limiting effect of the gap junction forces the signal along cable 2 to decay with diameter past a certain value, thus generating an optimal diameter for signal transmission.

A necessary requirement for an optimal diameter to appear is that at least one of the two coupled cells has a cable-like structure (Fig. 4). Two isopotential coupled cells do not exhibit an optimal diameter. A further general rule is that any parameter changes that result in an attenuation of the voltage signal along the coupled cables results in a sharpening of the diameter tuning curve along the second cable (Figs. 3-5).

Action potentials effectively voltage clamp the membrane to the action potential waveform. Thus, the occurrence of an action potential in a neuron presynaptic to the gap junction will produce a maximal coupling potential for a unique optimal diameter. This is shown in a simplified configuration in Figs. 9 and 10. Note that an action potential does not produce an optimal diameter in a single cable (Fig. 10A). Furthermore, a strong chemical synapse that produces a strong conductance change is effectively equivalent to a voltage clamp input and will produce an optimal diameter in processes that are gap-junctionally coupled to the cell receiving the synaptic input. However, such input does not produce an optimal diameter in a single cable (Holmes 1989).

A further effect of the sensitivity of electrical coupling to cable diameter is that a signal (e.g. an action potential) may be transmitted with identical attenuation into cables of different diameters if their diameters lie at either side of the optimal value, for instance at 1 and 30 μm in Fig. 9. However, the synaptic integration properties of these two cables can be substantially different due to the different membrane properties of cables of different diameter (see coupling potential shapes in Fig. 9 at 1 and 30 μm, and Fig. 10B). Additionally, the appearance of the optimal diameter is not restricted to a pair of coupled cables, to cables coupled only at their ends, or to sealed cables. Finite sealed (Fig. 8A,B) or very long cables coupled in middle positions (Fig. 8C,D), as is the case with axo-axonal (Schmitz et al. 2001; Yasargil and Sandri 1990) and dendro-dendritic gap junctions (Fukuda and Kosaka 2003; Matsumoto et al. 1988; Sotelo et al. 1986), respectively, as well as open-ended cables (not shown), all exhibit optimal diameters. Moreover, an architecture of series of cables coupled end-to-end, which may be considered equivalent to some types of muscle cells such as cardiac myocytes (Joyner et al. 1984), also demonstrates an optimal diameter.

Another important property of the optimal diameter is that, in a branched post-junctional structure, it is local to the daughter branch (Fig. 6). Thus, a mother cable and its daughter branches may be tuned to have distinct diameters near their optimal values depending on their different membrane properties. This is potentially important because it may allow for functional compartmentalization based purely on this geometrical condition.

Diameter and gap junction conductance measurements

Optimal signal transfer via gap junctions is a local effect (Fig. 6). Thus, any direct experimental test of such optimal signaling requires measurement of gap junction conductances specific to the coupled processes. Few such simultaneous measurements have been performed (Fukuda and Kosaka 2003). We predict the optimal diameter value for normally observed gap junction conductances and input resistances to be in the sub-micrometer to micrometer range. This appears to be in accordance with observed dendrite diameters where gap junctions have been found and their conductances estimated (Fukuda and Kosaka 2003; Pappas and Bennett 1966; Tamas et al. 2000). Using equations 7, 9 and 10 for cables coupled along middle positions (see Methods) we estimated the optimal dendrite diameter of hippocampal basket cells with dendrite length and gap junction position values reported by Fukuda and Kosaka (2003), Rm and Ri values reported by Saraga et al (2003), and Rc values reported by Fukuda and Kosaka (2003) and Traub et al. (2001). Average membrane parameter values (i.e. dendrite length = 500 μm, Rm = 40 kΩcm2, Ri = 120 Ωcm, Rc = 3×107 Ω, gap junction postion =300 μm) give an optimal diameter of 1.3 μm. This optimal diameter value is remarkably close to the actual dendrite diameter values reported by Fukuda and Kosaka (2003), who found most of the dendrites of hippocampal basket cells making gap junctions to have small to medium diameter values (0.5 to 1.5 μm). We therefore predict that, in systems that rely on electrical signaling via gap junctions, coupled processes will have diameters around the optimal value for maximum signal transfer. On the other hand, systems whose gap junctions are modulated by neurotransmitters, hormones and metabolites (Gladwell and Jefferys 2001; Johnson et al. 1994; McMahon and Brown 1994; McVicar and Shivers 1984; Rorig and Sutor 1996) may have diameters close to or far from the optimal value depending on the hormonal or modulatory environment.

Developmental effects

Dendritic pruning during critical stages of development is important in the establishment of functional networks and is known to rely on the strengthening of correlated signals between cells (Hata et al. 1999; Kandler and Katz 1998). Neuronal structure and circuit formation during these critical periods rely on chemical and electrical coupling (Kandler and Katz 1998), and dendrite morphology (branching, length, spine density) is regulated by activity (Konur and Ghosh 2005). Gap-junctionally coupled processes that are most strongly coupled (e.g. at an optimal diameter) are thus likely to be selected and preserved during pruning. Consequently, it is conceivable that cable diameter, like other morphological neuronal features, may also be regulated during development (Konur and Ghosh 2005) and thus be another important variable in the determination of network structure and activity.

Network synchronization

Gap-junctional coupling among interneurons is important in the generation of synchronous activity in different regions of the mammalian brain (Connors and Long 2004). These interneuron networks involve co-localized chemical and electrical coupling (Beierlein et al. 2000; Friedman and Strowbridge 2003; Tamas et al. 2000; Traub et al. 2001) both of which may be involved in producing synchrony (Chow and Kopell 2000; Kopell and Ermentrout 2004; Lewis and Rinzel 2003). We have shown that optimal diameter depends on the membrane resistance of the coupled processes, particularly when this resistance is low (Fig. 3A). Therefore, when chemical synaptic input is low (high Rin), pairs of neurons could be tuned to be maximally coupled via gap junctions allowing for effective synchronization. Such a mechanism may be at work where synchrony appears after blocking synaptic transmission (Angstadt and Friesen 1991). Alternatively, synchronization can be driven by chemical synaptic inputs (low Rin), bringing the electrical coupling-based signaling out of optimal range. In this way synchrony could be assured via different cellular mechanisms. Moreover, electrical coupling and synaptic inputs can act synergistically to bring about synchrony (Friedman and Strowbridge 2003; Kopell and Ermentrout 2004; Tamas et al. 2000).

Acknowledgments

Grants

This work was supported by NIH grants MH60605 (FN), MH64711 (JG) and NSF IBN-0090250.

References

- Angstadt JD, Friesen WO. Synchronized oscillatory activity in leech neurons induced by calcium channel blockers. J Neurophysiol. 1991;66:1858–1873. doi: 10.1152/jn.1991.66.6.1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beierlein M, Gibson JR, Connors BW. A network of electrically coupled interneurons drives synchronized inhibition in neocortex. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:904–910. doi: 10.1038/78809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bem T, Rinzel J. Short duty cycle destabilizes a half-center oscillator, but gap junctions can restabilize the anti-phase pattern. J Neurophysiol. 2004;91:693–703. doi: 10.1152/jn.00783.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthold C-H. Morphology of normal peripheral axons. In: Waxman SG, editor. Physiology and Pathobiology of Axons. Raven Press; New York: 1978. pp. 3–63. [Google Scholar]

- Chow CC, Kopell N. Dynamics of spiking neurons with electrical coupling. Neural Comput. 2000;12:1643–1678. doi: 10.1162/089976600300015295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman PA, Miller RF. Measurement of passive membrane parameters with whole-cell recording from neurons in the intact amphibian retina. J Neurophysiol. 1989;61:218–230. doi: 10.1152/jn.1989.61.1.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connors BW, Long MA. Electrical synapses in the mammalian brain. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2004;27:393–418. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.26.041002.131128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman D, Strowbridge BW. Both electrical and chemical synapses mediate fast network oscillations in the olfactory bulb. J Neurophysiol. 2003;89:2601–2610. doi: 10.1152/jn.00887.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda T, Kosaka T. Ultrastructural study of gap junctions between dendrites of parvalbumin-containing GABAergic neurons in various neocortical areas of the adult rat. Neuroscience. 2003;120:5–20. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00328-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladwell SJ, Jefferys JG. Second messenger modulation of electrotonic coupling between region CA3 pyramidal cell axons in the rat hippocampus. Neurosci Lett. 2001;300:1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)01530-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartline DK, Castelfranco AM. Simulations of voltage clamping poorly space-clamped voltage-dependent conductances in a uniform cylindrical neurite. J Comput Neurosci. 2003;14:253–269. doi: 10.1023/a:1023208926805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hata Y, Tsumoto T, Stryker MP. Selective pruning of more active afferents when cat visual cortex is pharmacologically inhibited. Neuron. 1999;22:375–381. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81097-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkin AL, Huxley AF. A quantitative description of membrane current and its application to conduction and excitation in nerve. J Physiol. 1952;117:500–544. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1952.sp004764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes WR. The role of dendritic diameters in maximizing the effectiveness of synaptic inputs. Brain Res. 1989;478:127–137. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)91484-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BR, Peck JH, Harris-Warrick RM. Differential modulation of chemical and electrical components of mixed synapses in the lobster stomatogastric ganglion. J Comp Physiol [A] 1994;175:233–249. doi: 10.1007/BF00215119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyner RW, Veenstra R, Rawling D, Chorro A. Propagation through electrically coupled cells. Effects of a resistive barrier. Biophys J. 1984;45:1017–1025. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(84)84247-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandler K, Katz LC. Coordination of neuronal activity in developing visual cortex by gap junction-mediated biochemical communication. J Neurosci. 1998;18:1419–1427. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-04-01419.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keener JP. The effects of gap junctions on propagation in myocardium: a modified cable theory. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1990;591:257–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb15094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kepler TB, Marder E, Abbott LF. The effect of electrical coupling on the frequency of model neuronal oscillators. Science. 1990;248:83–85. doi: 10.1126/science.2321028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konur S, Ghosh A. Calcium signaling and the control of dendritic development. Neuron. 2005;46:401–405. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopell N, Ermentrout B. Chemical and electrical synapses perform complementary roles in the synchronization of interneuronal networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:15482–15487. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406343101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBeau FE, Traub RD, Monyer H, Whittington MA, Buhl EH. The role of electrical signaling via gap junctions in the generation of fast network oscillations. Brain Res Bull. 2003;62:3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2003.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis TJ, Rinzel J. Dynamics of spiking neurons connected by both inhibitory and electrical coupling. J Comput Neurosci. 2003;14:283–309. doi: 10.1023/a:1023265027714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto A, Arnold AP, Zampighi GA, Micevych PE. Androgenic regulation of gap junctions between motoneurons in the rat spinal cord. J Neurosci. 1988;8:4177–4183. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-11-04177.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon DG, Brown DR. Modulation of gap-junction channel gating at zebrafish retinal electrical synapses. J Neurophysiol. 1994;72:2257–2268. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.5.2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McVicar LK, Shivers RR. Crustecdysone-induced modulation of electrical coupling and gap junction structure in crayfish hepatopancreatocytes. Tissue Cell. 1984;16:917–928. doi: 10.1016/0040-8166(84)90071-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikelberg FS, Drance SM, Schulzer M, Yidegiligne HM, Weis MM. The normal human optic nerve. Axon count and axon diameter distribution. Ophthalmology. 1989;96:1325–1328. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(89)32718-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappas GD, Bennett MV. Specialized junctions involved in electrical transmission between neurons. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1966;137:495–508. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1966.tb50177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeuty B, Mato G, Golomb D, Hansel D. Electrical synapses and synchrony: the role of intrinsic currents. J Neurosci. 2003;23:6280–6294. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-15-06280.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabbah P, Golowasch J, Nadim F. Effect of electrical coupling on ionic current and synaptic potential measurements. J Neurophysiol. 2005 doi: 10.1152/jn.00043.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rall W. Core conductor theory and cable properties of neurons. In: Kandel ER, editor. Handbook of Physiology (Section 1, The Nervous System I, Cellular Biology of Neurons) American Physiological Society; Bethesda, MD: 1977. pp. 39–97. [Google Scholar]

- Rall W, Segev I, Rinzel J, Shepherd GM. The theoretical foundation of dendritic function : selected papers of Wilfrid Rall with commentaries. MIT Press; Cambridge, Mass.: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Rorig B, Sutor B. Serotonin regulates gap junction coupling in the developing rat somatosensory cortex. Eur J Neurosci. 1996;8:1685–1695. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1996.tb01312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saraga F, Wu CP, Zhang L, Skinner FK. Active dendrites and spike propagation in multi-compartment models of oriens-lacunosum/moleculare hippocampal interneurons. J Physiol. 2003;552:673–689. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.046177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz D, Schuchmann S, Fisahn A, Draguhn A, Buhl EH, Petrasch-Parwez E, Dermietzel R, Heinemann U, Traub RD. Axo-axonal coupling. a novel mechanism for ultrafast neuronal communication. Neuron. 2001;31:831–840. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00410-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman A, Rinzel J. Model for synchronization of pancreatic beta-cells by gap junction coupling. Biophys J. 1991;59:547–559. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(91)82271-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotelo C, Gotow T, Wassef M. Localization of glutamic-acid-decarboxylase-immunoreactive axon terminals in the inferior olive of the rat, with special emphasis on anatomical relations between GABAergic synapses and dendrodendritic gap junctions. J Comp Neurol. 1986;252:32–50. doi: 10.1002/cne.902520103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamas G, Buhl EH, Lorincz A, Somogyi P. Proximally targeted GABAergic synapses and gap junctions synchronize cortical interneurons. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:366–371. doi: 10.1038/73936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traub RD, Kopell N, Bibbig A, Buhl EH, LeBeau FE, Whittington MA. Gap junctions between interneuron dendrites can enhance synchrony of gamma oscillations in distributed networks. J Neurosci. 2001;21:9478–9486. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-23-09478.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traub RD, Pais I, Bibbig A, LeBeau FE, Buhl EH, Hormuzdi SG, Monyer H, Whittington MA. Contrasting roles of axonal (pyramidal cell) and dendritic (interneuron) electrical coupling in the generation of neuronal network oscillations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:1370–1374. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337529100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traub RD, Schmitz D, Jefferys JG, Draguhn A. High-frequency population oscillations are predicted to occur in hippocampal pyramidal neuronal networks interconnected by axoaxonal gap junctions. Neuroscience. 1999;92:407–426. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00755-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasargil GM, Sandri C. Topography and ultrastructure of commissural interneurons that may establish reciprocal inhibitory connections of the Mauthner axons in the spinal cord of the tench, Tinca tinca L. J Neurocytol. 1990;19:111–126. doi: 10.1007/BF01188443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]