Abstract

GTPases are molecular switches that regulate a wide-range of cellular processes. The GPN-loop GTPase (GPN) is a sub-family of P-loop NTPase that evolved from a single gene copy in archaea to triplicate paralog genes in eukaryotes, each having a non-redundant essential function in cell. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, yGPN1 and yGPN2 are involved in sister chromatid cohesion mechanism, whereas nothing is known regarding yGPN3 function. Previous high-throughput experiments suggested that GPN paralogs interaction may occur. In this work, GPN|GPN contact was analyzed in details using TAP-Tag approach, yeast two-hybrid assay, in silico energy computation and site-directed mutagenesis of a conserved Glu residue located at the center of the interaction interface. It is demonstrated that this residue is essential for cell viability. A chromatid cohesion assay revealed that, like yGPN1 and yGPN2, yGPN3 also plays a role in sister chromatid cohesion. These results suggest that all three GPN proteins act at the molecular level in sister chromatid cohesion mechanism as a GPN|GPN complex reminiscent of the homodimeric structure of PAB0955, an archaeal member of GPN-loop GTPase.

Keywords: GPN-loop-GTPase, chromatid cohesion, heterodimer, paralogous interactions, P-loop NTPase

Introduction

Cohesins play a central role in pairing of duplicated chromosomes1-3 and in a wide-range of other functions, such as double-strand DNA repair4 and transcriptional regulation.4-7 For efficient activity of cohesins, numerous additional proteins are required. Recently, two proteins, namely the GPN-loop GTPases GPN1 and GPN2, have been shown to be involved in cohesion dissociation8 and establishment,9 respectively.

GPN-loop GTPases are found in all sequenced eukaryotes and in almost all archaea but not in bacteria.10 In eukaryotes, three distinct homologs (GPN1, GPN2 and GPN3) are found, whereas a single copy is found in archaea. This family of conserved GTPases has been named GPN-loop GTPases (GPN) due to the presence of a conserved Gly-Pro-Asn motif inserted into the GTPase core-fold.11 These GPN-loop GTPases belongs to monophyletic GTPases superclass within P-loop containing nucleoside triphosphate hydrolases fold, which is divided into two large groups designated TRAFAC (after translation factors) and SIMIBI (after signal recognition particle, MinD and BioD) (see review in ref. 12). This later group includes, among others, a group of metabolic enzymes with kinase activity, signal recognition particle (SRP) GTPases and the assemblage of MinD-like ATPases, which are involved in protein localization, chromosome partitioning and membrane transport.12 Up to now, the three-dimensional structure of a GPN-loop GTPase, that of PAB0955 from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus abyssi, has been determined. Its structural study revealed a general fold related to SIMIBI GTPase.13 The crystal structure also shows that this archaeal GPN is homodimeric.11 In the yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, individual deletions of either gene, YJR072C (yGPN1), YOR262W (yGPN2) or YLR243W (yGPN3), are lethal.14 Thus, these three paralogous GTPases fulfill an essential function and are not functionally interchangeable.

The present work sheds new lights on yGPNs function both at the molecular and cellular level. Pull-down experiments using yGPN1 as bait first showed that in yeast yGPN1 can be associated with yGPN2 or yGPN3. Then, in order to characterize the molecular basis of these complexes, and in the absence of crystallographic data, comparative models of the three yGPN paralogs were built using PAB0955 as a template, and modeling of yGPN1|yGPN2 and yGPN1|yGPN3 complexes were performed. These complexes revealed putative critical residue at the interface of two monomers: Glu112 for yGPN1 and yGPN2, and Glu110 for yGPN3. Mutations of these residues were realized, and it was demonstrated using a two-hybrid system assay that they are essential for paralogous interactions. Based on a sister chromatid cohesion assay, we also found that overexpression of yGPN3 protein promotes sister chromatid separation during anaphase.

Results

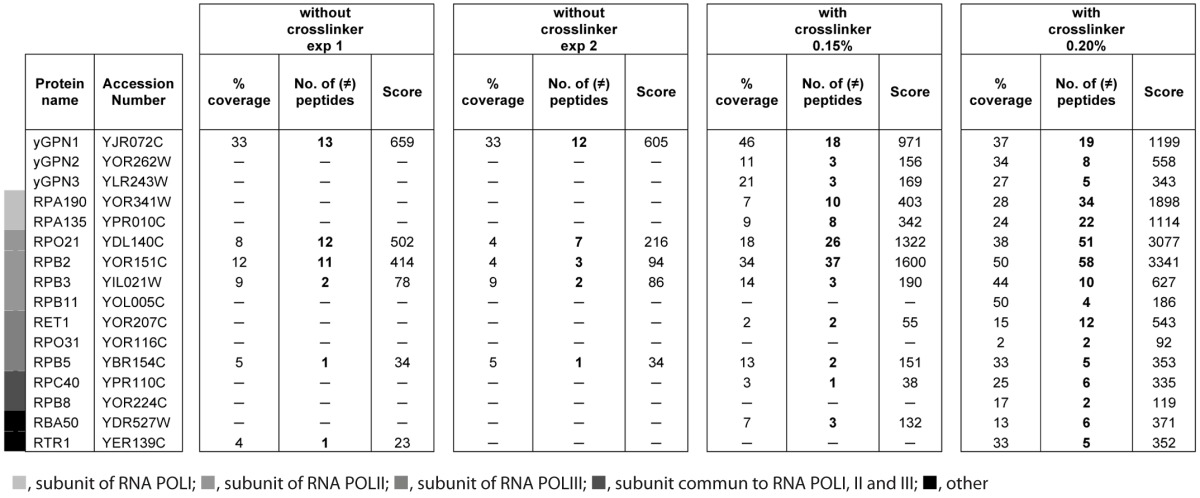

yGPN2 and yGPN3 belongs to the yGPN1 interacting network

Large-scale two-hybrid experiments in S. cerevisiae suggested that yGPN2 and yGPN3 proteins could interact with yGPN1.15,16 Recently, the co-purification of tagged yGPN1 with yGPN2 has been demonstrated by mass spectrometry in S. cerevisiae.17 Here, we show that yGPN1|yGPN3 interaction could also be detected using tandem affinity tag strategy coupled to a shotgun mass spectrometry approach. For this, yGPN1 TAP-tagged protein was chosen, and formaldehyde was applied on intact cells harvested at the exponential phase to freeze transient interactions. Purified complexes were subjected to a short-run electrophoresis in denaturing condition and then in-gel proteolyzed with trypsin. The resulting peptides were identified by nanoLC-MS/MS. A total of 815 different peptides were detected. Table 1 reports all the proteins identified with at least two different detected peptides and filtered of contaminants frequently observed with the TAP-TAG assay. Among these, 16 proteins are GPN proteins as well as proteins belonging to the transcription machinery, six of which are also found in conditions without the cross-linker folmaldehyde (Table 1). As expected, the yGPN1 is the most detected protein, with about 15 different peptides observed by nano LC-MS/MS. Besides RNAPII subunits, Rpb1, Rpb2, Rpb3 and Rpb5, and yGPN2 protein, which have already been observed as interacting with yGPN1 in previous TAP-Tag studies,17 10 new interacting proteins were found co-purified with yGPN1: two subunits of RNAPI (Rpa190 and Rpa135), one subunit of RNAPII (Rpb11), two subunits of RNAPIII (Ret1 and Rpo31), two RNA polymerase subunits common to RNA polymerases I and III (Rpc40) and RNA polymerases I, II and III (Rpb8), RTR1 (Rpb1 phosphatase), Rba50 (RNA polymerase II-associated protein) and yGPN3. We observed that most of the GPNs interactions were only detected in the presence of a cross-linker, which may allow the freezing of transient or weak interactions.

Table 1. Spectral count differences detected with or without cross-linker.

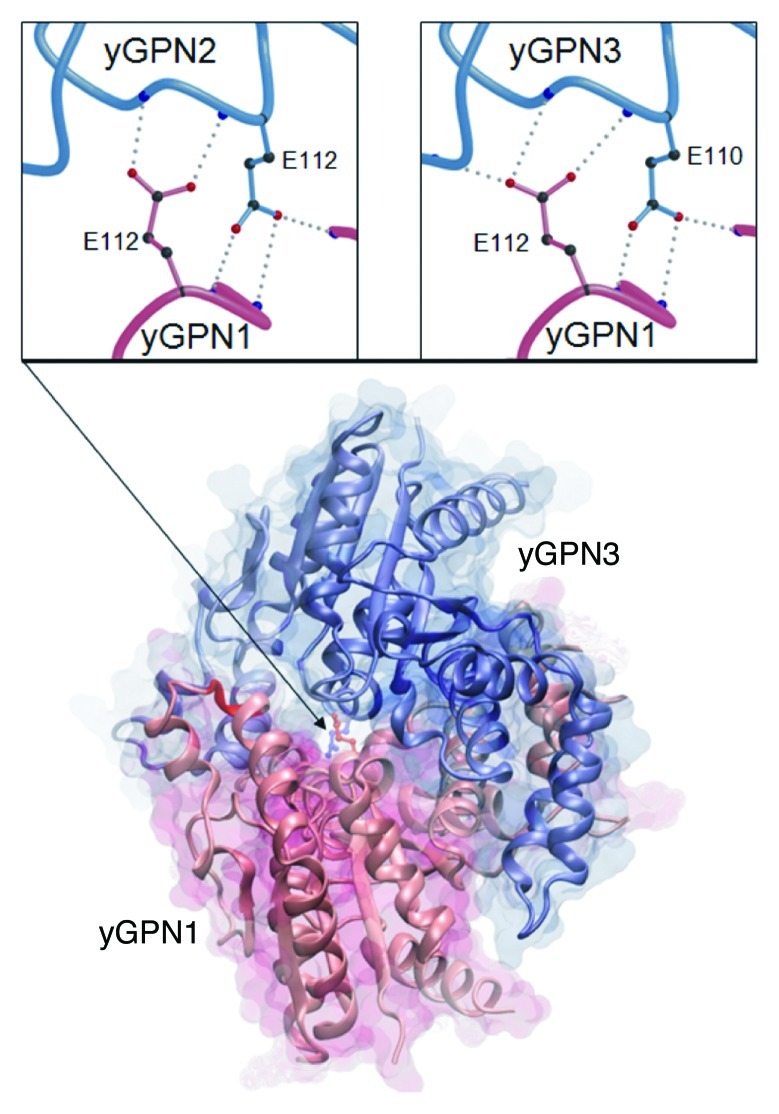

Comparative modeling of yGPN1, yGPN2 and yGPN3

To understand the molecular basis of possible direct interactions between yGPN1|yGPN2 and yGPN1|yGPN3, molecular models were sought for each of these proteins as well as their putative complexes using our in-house modeling pipeline. The closest identified protein template in the Protein Data Bank18 is the structure of the archaeal protein PAB0955 from Pyrococcus abyssi.19 The sequence identity between yGPNs and PAB0955 is relatively low, around 20%, but there is a significant similarity in the first half of the sequence alignment, which gave us high confidence in the choice of the template. Stereochemical and energetic evaluations of the three molecular models are shown in Table 2. Values indicate that all three models are of good quality compared with the 2.3Å-resolution crystallographic structure of PAB0955. The template PAB0955 was described as being a homodimer,19 and we wondered whether heterodimers yGPN1|yGPN2 and yGPN1|yGPN3 are plausible. For this, we built molecular models for each of these heterodimers as described in the methods section. This stage was straightforwardly executed, taking advantage of the dimeric structure of the template PAB0955. Figure 1 displays the yGPN1|yGPN3 complex. Very few adjustments were required to fit side chain conformations in both heterodimers. Root mean-square deviations of Cα atoms (Cα-RMSDs) were calculated after a global superimposition of these complexes onto the dimeric PAB0955 using the sup3d software program,20 and both gave 0.26 Å for yGPN1|yGPN2 and yGPN1|yGPN3 dimers. The computed buried surface area of yGPN1|yGPN2 is 3860 Å2 and 3706 Å2 for yGPN1|yGPN3 compared with 3988 Å2 in the dimeric PAB0955. All these parameters indicate that heterodimers yGPN1|yGPN2 and yGPN1|yGPN3 present energetic and geometrical values close to that of the dimeric template.

Table 2. Stereochemical and energetic analysis of yGPN comparative models.

| Score | PAB0955 | yGPN1 | yGPN2 | yGPN3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PROSA |

-9.32 |

-6.37 |

-6.96 |

-7.44 |

| HBOND |

398 |

383 |

366 |

353 |

| PROCHECK |

91.7 |

90.5 |

89.2 |

93.5 |

| DDFIRE |

-669.1 |

-604.9 |

-613.7 |

-598.9 |

| FRST |

-33162.4 |

-11619.5 |

-14911.3 |

-18082.2 |

| XPLOR |

-447.3 |

-459.6 |

-351.7 |

-570.9 |

| MOLPROBITY |

2.42 (52nd percentile) |

2.28 (60th percentile) |

2.44 (50th percentile) |

2.21 (64th percentile) |

| Cα-RMSD | 0.0 | 0.141 (241) | 0.173 (236) | 0.186 (236) |

Values for PROSA are Z-scores obtained from the Prosa2000 package38 (lower values indicate better structures).

Values for HBOND show the total number of detected hydrogen bonds using heavy atoms of the structures (in-house tool, higher values indicate better structures).

Values for PROCHECK indicate the percentage of dihedral angle (φ,ψ) values located within the most favored regions37 (higher values indicate better structures).

Values for DDFIRE are obtained from the DFIRE-pseudo potential function54 in units of kcal/mol (lower values indicate better structures).

Values for FRST are obtained from the pseudo-potential energy FRST40 in pseudo units (lower values indicate better structures).

Values for XPLOR are those from the non-bonded van der Waals potential energy terms using Charmm22 force field44 in unit of kcal/mol (lower values indicate better structures).

Values for MolProbity were obtained from the web server.55 The lower the score, the better the structure quality; 100th percentile represents an ideal protein structure whereas 0th percentile represents the worst case.

Values for Cα-RMSD obtained from the sup3d global superposition20 indicate the RMSD between Cα atoms of the PAB0955 template and Cα atoms from each model. The number of parenthesis indicated the number of superimposed residues that have their Cα-RMSDs below the given value. The total alignment length is 274 residues.

Figure 1. Comparative model of the yGPN1 (red)|yGPN3 (blue) interaction complex. Secondary structure elements are indicated by arrows for β-strands and helicoidal springs for α-helices. Top panels show close-up views on the conserved Glu residues located at the yGPN1|yGPN2 (left) and yGPN1|yGPN3 (right) interfaces. The Cα trace of molecules is shown as tubes, whereas amino acid side-chains are shown using colored balls and sticks (black for carbon, red for oxygen and blue for nitrogen). Hydrogen bonds made between the conserved Glu residues of one partner with backbone atoms of the other partner are shown as gray dots. Each Glu residue makes three side-chain-to-main-chain hydrogen bonds except in the yGPN1|yGPN2 dimer where a proline is present in yGPN2 (no nitrogen backbone atom available). The transparent molecular surface was built using the surf tool of VMD,51 whereas the top panels were built using Molscript52 and rendered using Raster3D.53

The conserved residues E112 in yGPN2 and E110 in yGPN3 are critical for in vivo yGPN1|yGPN2 and yGPN1|yGPN3 interactions

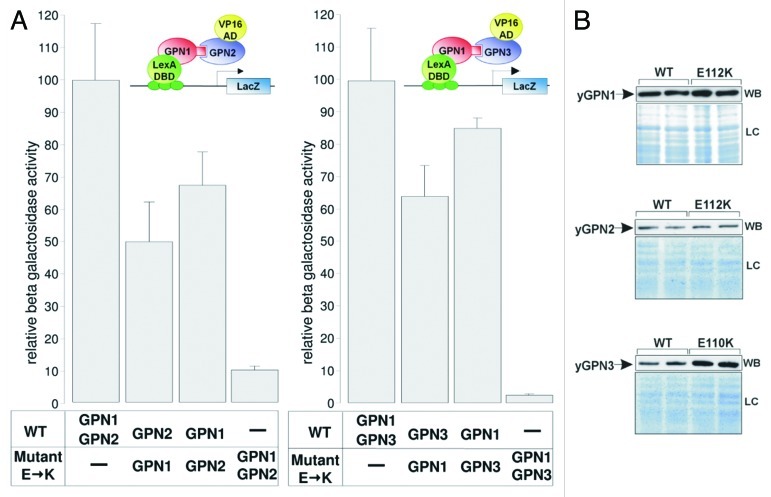

A detailed analysis of the dimeric structure of the archaeal PAB0955 protein revealed the presence of a buried charged residue at the dimeric interface, the glutamate at position 107 (E107), which corresponds to E112 in yGPN1, E112 in yGPN2 and E110 in yGPN3. This amino acid is located right next to the G3 box belonging to the core structure of the GTPase active site. It is strictly conserved among the GPN-GTPase (Fig. S1). The presence of several hydrogen bonds between side-chain atoms of Glu residue and several nitrogen backbone atoms suggests that this residue plays an important role in the energetics of the complex interface (Fig. 1). Preliminary in silico mutagenesis was performed at this position with every other 19 amino acids (AA) using in-house software.21 It was found that most AA replacements were deleterious. The energy difference ΔE (EMut – EWT) for lysine (K) replacements in yGPN1|yGPN3 complexes are indicated in Table 3. It shows that the double mutants yGPN1(E112K)|yGPN2(E112K), yGPN1(E112K)|yGPN3(E110K) are clearly less stable than single mutants. It should be noted that in their respective monomeric form, yGPN1Glu112, yGPN2Glu112 and yGPN3Glu110 are fully solvent-exposed. Consequently, computational replacement of these residues in monomeric GPN proteins did not reveal disruptive effects. To experimentally confirm that Glu110/112 is critical for GPN complexes, a two-hybrid assay was performed. In the wild-type strain, the constructs LexA-yGPN1, VP16-yGPN2 and pLexA-LacZ, or LexA-yGPN1, VP16-yGPN3 and pLexA-LacZ were introduced. Wild-type GPN genes were replaced by mutated ones (yGPN1E112K, yGPN2E112K and yGPN3E110K). The relative β-galactosidase activities of the two-hybrid assays are shown in Figure 2A. These two-hybrid assays clearly demonstrated that the replacement of a single residue in yGPNs, namely yGPN1E112, yGPN2E112 or yGPN3E110, significantly affected yGPN1|yGPN2 and yGPN1|yGPN3 interaction. While only partial loss of interaction between GPNWT and mutated GPNs was observed, almost total abolishment of the interaction was observed when the Glu residues were mutated in both GPNs (Fig. 2A). Because any change in protein amounts between GPN partners could alter the interpretation of two-hybrid results, we performed a western blot analysis showing that the level of mutated form yGPN1E112K, yGPN2E112K and yGPN3E110K did not decrease compared with the wild-type form (Fig. 2B). In summary, we demonstrated that the E110K/E112K substitutions markedly alter the in vivo interaction between yGPN1|yGPN2 and yGPN1|yGPN3.

Table 3. Mutational energetic cost for Glu→Lys replacement in yGPN|yGPN interactions.

| ΔE (kcal/mol) | |

|---|---|

| yGPN1(E112K)|yGPN2 |

+32 |

| yGPN1|yGPN2(E112K) |

+139 |

| yGPN1(E112K)|yGPN2(E112K) |

+220 |

| yGPN1(E112K)|yGPN3 |

+98 |

| yGPN1|yGPN3(E112K) |

+177 |

| yGPN1(E112K)|yGPN3(E110K) | +225 |

Figure 2. Effect of Glu→ Lys substitutions on GPNs interactions. (A) Two-hybrid assays were performed to measure the level of interaction between yGPN1|yGPN2 and yGPN1|yGPN3. Constructs tested are indicated in the bottom panel, and interaction data from yeast two-hybrid assays are indicated in relative β-galactosidase units for each combination of GPNs. WT and mutant. E→K symbolize the Glu residue substitution to Lys (E112 for yGPN1 and yGPN2 and E110 for yGPN3), respectively. Error bars represent SD from the mean value of the series of five individual measurements, which were representative of at least two independent experiments performed on two distinct clones. (B) Western blotting (WB) of WT and mutant GPNs from two-hybrid assays, using anti-LexA antibody (Santa Cruz) for GPN1 detection and anti-VP16 antibody (Santa Cruz) for GPN2 and GPN3). Loading controls (LC) stained with coomassie blue SafeStain (Invitrogen) are shown (bottom panel). It shows that the expression level does not decrease in mutant proteins.

The interaction between GPNs is essential for their cellular function

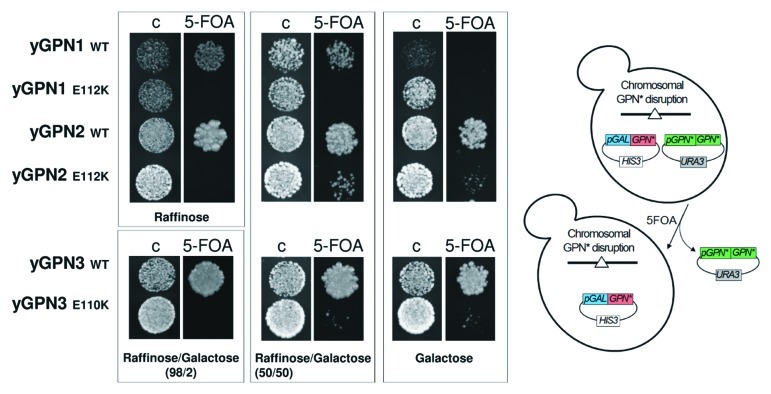

To establish whether the yGPN1|yGPN2 and yGPN1|yGPN3 interactions are important for the survival of yeast cells, a genetic test using the plasmid-shuffling method with 5-FOA selection was performed. Haploid strains, which lack the genomic copy of yGPN1, yGPN2 or yGPN3, were rescued by the URA3 shuffle plasmid encoding the wild-type form of yGPN1, yGPN2 or yGPN3 genes, respectively. These strains were transformed by a second plasmid whose expression was placed under the control of the pGAL10 galactose-inducible promoter and which contains appropriate WT GPNs or mutated forms for yGPN1E112, yGPN2E112 or yGPN3E110. Exponentially growing cells were spotted onto selective medium (containing 5-FOA), allowing to shuffle out the URA3 plasmids encoding the wild-type forms of yGPNs (Fig. 3). Plated cells were grown with different carbon sources such as raffinose, raffinose-galactose (98/2 and 50/50) and galactose to trigger an increasing induction of GPN proteins expression. Figure 3 shows that after shuffling out the URA3 plasmid expressing the wild-type form of GPN, the copy of WT yGPN1, -2 and -3 under the control of pGAL10 were able to complement the deleted endogenous copy for cells growth. However, this complementation is dependent on the carbon source used, as, for instance, overexpression (galactose) of yGPN1 (Fig. 3) and underexpression (raffinose) of yGPN3 (Table S1) drastically inhibited cell growth. Cells expressing yGPN1E112K mutant are unable to grow whatever the carbon source, and cells expressing yGPN2E112K and yGPN3E110K mutants grow only if GPN expression is strongly induced with galactose (50% or 100%) (Fig. 3). We noted that the cell growth rates of these yGPN2E112K and yGPN3E110K mutants are nonetheless significantly reduced compared with the wild-type form in liquid culture. Another substitution (yGPN2E112A and yGPN3E110A) was also tested, as an alanine residue was predicted to have a milder effect on the yGPN1|yGPN2 and yGPN1|yGPN3 interactions than a lysine. However, similar results as those described above for Glu substitutions to Lys were obtained (Table S1). To address the specificity of the Glu mutation on cell viability, additional mutations were tested on residues proximal to the Glu residue. The highly conserved residues Gln, Ile/Val were chosen, and the following mutants generated: yGPN1Q110A, yGPN1I111A, yGPN2Q110A, yGPN2V111A, yGPN3Q108A and yGPN3I109A. From the molecular models, these mutations were predicted to have minor effect on the yGPN1|yGPN2 and yGPN1|yGPN3 interactions. Experimental results show that, indeed, these mutations do not affect cell viability and cell growth whatever the carbon source used (Table S1). In conclusion, glutamate residues at position 112 in yGPN1 and yGPN2 and 110 in yGPN3 are crucial for both the interactions between yGPN1|yGPN2 and yGPN1|yGPN3 and cell viability. Otherwise, mutations in the same region not predicted to interfere with these interactions do not affect cell viability. This strongly suggests that yGPN1|yGPN2 and yGPN1|yGPN3 interactions are crucial for cell viability.

Figure 3. Plasmid shuffle complementation tests of GPNs wild-type (WT) and mutants (E112K for yGPN1 and yGPN2 and E110K for yGPN3). Cells were grown on control (C) or 5-fluoroorotic acid (FOA) medium. Cells were incubated for 3 d at 30°C with different carbon sources, such as raffinose, raffinose/galactose (98/2 and 50/50) and galactose, to trigger an increasing induction of GPN proteins expression.

yGPN3 is involved in chromosome segregation

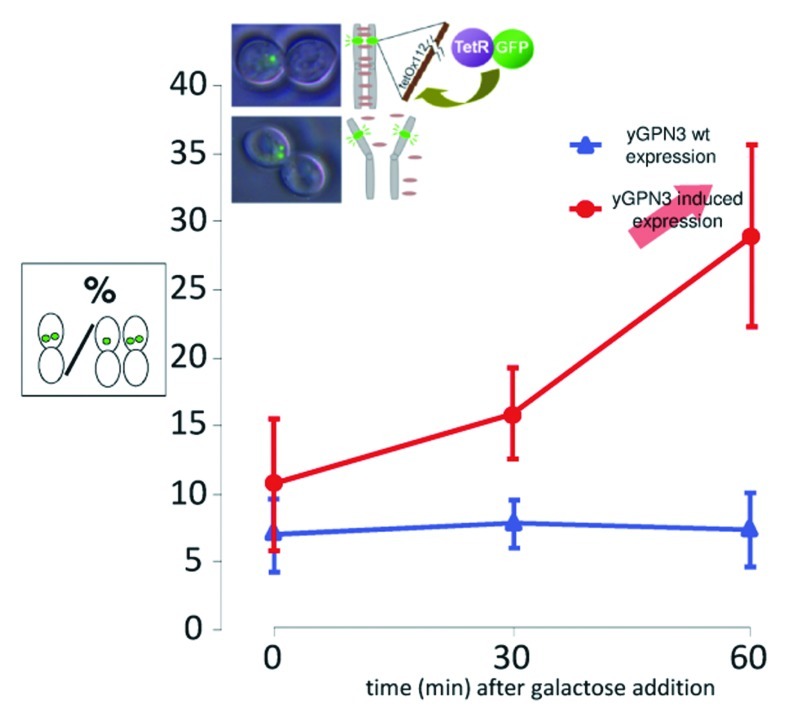

To assess whether yGPN3 plays a role in sister chromatid cohesion, a cohesion assay with the GFP-tagged chromosome strategy as described earlier8 was performed on yGPN3. Because yGPN3 was previously found to be an essential gene,14 we first constructed a conditional ΔyGPN3 strain by introducing in S. cerevisiae, a plasmid encoding the wild-type yGPN3 gene whose expression was placed under the control of the galactose-inducible promoter pGAL10 and then inactivating the chromosomal copy. To GFP-tag the chromosome of the wild-type BY4742 and ΔyGPN3 isogenic strains, tet0112 and TetR-GFP constructions were inserted at the URA3 and LEU2 loci, respectively, in both strains. Chromatid cohesion was examined after nocodazole treatment to block cells at the G2/M transition. Wild-type and yGPN3-regulatable mutant cells were grown to mid-log phase, exposed to nocodazole, and then yGPN3 higher expression was induced with the addition of galactose. After 30 and 60 min of induction, cells were harvested, and sister chromatid cohesion was estimated by counting among the doublet cells with a large bud, those having one or two GFP dots. Figure 4 shows representative microscopy observations where the GFP dots are clearly distinguished. The ratio of cells with premature separation of sister chromatids is plotted for both strains as a function of time (Fig. 4). For the wild-type strain, the ratio of cells with two distinct GFP dots was below 8% and remained stable after galactose induction. On the contrary, the mutant strain exhibited an increase in the number of cells with two-distinct GFP dots from 11% at t = 0 to 28% at t = 60 min after induction. We concluded from these data that higher expression of yGPN3 leads to a severe defect in sister chromatid cohesion, and, thus, the function of yGPN3 is related to this important mechanism.

Figure 4. Cohesion defects increase upon yGPN3 overexpression. The graph represents the percentage of cells with double GFP dots in strain arrested in metaphase with nocodazole. yGPN3 expression was triggered by addition of galactose in the medium and cells were counted 30 and 60 min after galactose addition. Error bars represent SD from the mean value of a series or three independent experiments. In each experiment, counting was performed on 100 cells.

Discussion

The GPN-loop GTPases genes are present in a single copy in almost all archaea and systematically in three copies (GPN1, GPN2 and GPN3) in all sequenced eukaryotic genomes. The deletion of GPN1, GPN2 or GPN3 gene in S. cerevisiae results in lethality.14 This points out that these three GTPases, unable to complement each other, perform separate functions in yeast cells. The analysis of a multiple sequence alignment and phylogram tree, constructed with GPN1, GPN2 and GPN3 genes from taxonomically distant species (Fig. S2 and 3), suggests that these GPN-loop GTPases have a common ancestor. The existence of functional divergence and a common ancestor22 between GPN1, GPN2 and GPN3 point out that these GPN-loop GTPases are related by duplication and therefore are paralogous genes.12

Systematic yeast two-hybrid assays performed on yeast GPNs15,16 suggested that some GPNs interact with each other. Using TAP-tag purification technique, yGPN|yGPN interactions were detected in yeast: GPN1|GPN217 and GPN1|GPN3 (this work). GPN1|GPN3 complex was also identified in human.23 The need to use a cross-linker in this work to freeze the interactions indicates that the association between the GPNs is probably transient and/or weak. The nature of this interaction suggests the probable existence of interchangeable interactions of yGPN1 with yGPN2 or yGPN3. In addition, neither two-hybrid systems could detect GPN1|GPN1, GPN2|GPN2, GPN3|GPN3 and GPN2|GPN3,15,16 nor could TAP-tag purification detect GPN2|GPN3 complexes.17,23 Knowing the dimeric structure of the GPN-loop GTPase PAB0955 from P. abyssi,11 it was hypothesized that yGPN1 may interact with yGPN2 or yGPN3 using a similar dimeric assembly. The in silico modeling revealed that the dimerization interface of PAB0955 was conserved in each yeast GPN-loop GTPase. Scrutiny of the GPN|GPN complexes revealed that a strictly conserved residue: yGPN1E112, yGPN2E112 or yGPN3E110, as well as PAB0955E107 in the template, is critical in the energetics of the interface interaction (Fig. 1). The structure analysis of GPNs reveals that this Glu residue is solvent-exposed in the monomeric form, and its replacement by the Lys or Ala residues is not predicted disruptive for the subunit itself. This prediction is consistent with the similar protein expression level observed between the WT and the Glu residue mutant forms of GPN using western blot assay (Fig. 2B). The yeast two-hybrid assay on various constructions: yGPN1WT|yGPN2WT, yGPN1WT|yGPN3WT, yGPN1E112K|yGPN2WT, yGPN1WT|yGPN2E112K, yGPN1E112K|yGPN2E112K, yGPN1E112K|yGPN3WT, yGPN1WT|yGPN3E110K and yGPN1E112K|yGPN3E110K revealed that the interaction is weaker when the Glu residue is absent from one of the two interacting partners and abrogated when the Glu residue is absent from both partners. The viability of mutants carrying the Glu substitutions was examined using 5-FOA shuffling assay. Glu substitution to Ala or Lys residue confers a lethal phenotype for yGPN, which can partially be rescued by overexpression in case of yGPN2 and yGPN3 (Fig. 3; Table S1). Finally, to investigate if the local backbone conformation carrying the Glu substitution is not critical for the structure of yGPN proteins, conserved proximal residues were also mutated to Ala: yGPN1Q110A, yGPN1I111A, yGPN2Q110A, yGPN2V111A, yGPN3Q108A and yGPN3I109A. In all these mutants, a normal growth phenotype was observed. Taken altogether, these observations show for the first time that this Glu residue is important for the GPNs interactions and strongly suggest that these interactions are crucial for GPN function. It begs the question whether this dimeric structural assembly is unique or not to GPN-GTPases. The GPN GTPases belongs to the P-loop containing nucleoside triphosphate hydrolases superfamily (class of α/β proteins, SCOP database24). In this superfamily, the cell division regulator MinD appears in many ways similar to the GPNs structure. Despite a low sequence identity between MinD and PAB0955 that was estimated to be around 6% according to a structure-based alignment made with sup3d,20 it was observed that the core of MinD structure25 superimposes onto that of PAB0955 structure with a root-mean-square deviation of 1 Å for 79 core Cα atoms (Fig. S4). MinD undergoes ATP-dependent dimerization in solution,26 and the crystal structure reveals that a conserved Glu126 residue is located at the dimer interface. This residue is located right next to the G3 box (Fig. S1) and corresponds to Glu107 in PAB0955 (Fig. S4). In conclusion, convergent evolutionary and molecular data strongly suggest that the interactions of GPN-GTPases paralogs are of heterodimeric nature in the cell.

It has been recently shown that yGPN1 and yGPN2 are involved in sister chromatid cohesion mechanisms.8,9 A systematic analysis to identify new proteins involved in maintenance of chromosome stability revealed that the temperature-sensitive yGPN2 mutant exhibited sister chromatid cohesion defects and was required for establishment of sister chromatid cohesion.9 Regarding yGPN1, it was established that cells overexpressing this protein during anaphase displayed defects in sister chromatid cohesion.8 Furthermore, repression of yGPN1 expression strongly disturbs cell cycle progression with an important S-phase delay and an abnormal timing in nuclei migrations during mitosis.8 Up to date, the function of yGPN3 had remained unknown. Here, we tested for the first time the implication of yGPN3 in this chromatid cohesion mechanism and discovered that, like yGPN1, overexpression of yGPN3 induces sister-chromatid defects. The fact that yeast GPN proteins have non-redundant functions that all participate in sister-chromatid cohesion mechanism demonstrates that they play a significant role in this cellular process.

Before being described as involved in sister chromatid cohesion mechanism, GPNs were first described in stable association with RNA polymerase subunits (refs. 15, 17, 23, 27 and 28) and transcription regulators.29 Later, studies refined this activity and demonstrated that GPN1 and GPN3 were essential to RNAPII nuclear import.17,27,30 Actually, with the formations gathered on the GPN-GTPases, it appears currently difficult to establish a correlation between the association of GPN-GTPases with RNA polymerase II and GPN-GTPases function in sister chromatid cohesion mechanism. However, recent works describe the existence of intertwining between these two mechanisms. For example, a DNA loop, allowing physical proximity between enhancer and promoter for activation of gene transcription, can be stabilized by the cohesion complex.31 We may hypothesize that the GPN-loop-GTPases, in addition to their chromosome pairing activity, could play a role in the connection of these two mechanisms.

Materials and Methods

Conditions for yeast growth

For chromatid cohesion assays, cells were grown in yeast extract/peptone/raffinose medium, supplemented with 4% of yeast extract/peptone/galactose medium at 30°C. For G2/M synchronization, cells were treated with 20 µg nocodazole (Sigma-Aldrich) per mL of medium for 3 h (doubling time). For galactose induction, 5% of galactose at 40 g/L was added. For TAP-tag experiment (Open Biosystems), yGPN1-interacting partners were isolated from yeast grown in 2 L of yeast extract/peptone/dextrose liquid medium until an OD at 600 nm of 0.8 was reached. For two-hybrid assays, cells were cultured in raffinose synthetic complete medium minus uracile and histidine (MP Biomedicals) supplemented with 0.2% of galactose synthetic complete medium minus uracile and histidine at 30°C. Yeast proteins for western blot were extracted from cells grown in raffinose synthetic complete medium minus histidine supplemented with 10% of galactose synthetic complete medium minus histidine at 30°C. For survival test on 5-FOA, cells were cultured in raffinose or raffinose/galactose (98/2) (for yGPN3 construct) synthetic complete liquid medium minus uracile and histidine. Cells with suitable dilution were spread on 5-FOA 2g/L agar plates containing raffinose, raffinose/galactose or galactose synthetic complete medium minus histidine. Plates were incubated for 2–3 d at 30°C until colonies were grown.

Construction of plasmids and yeast strains

All the strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table S2. All the constructed and transformed strains are derived from the sequenced strain S288C. For the construction of conditional alleles of yGPN3, a PCR-based gene deletion strategy was used to generate a start-to-stop codon deletion of ylr243W. The disrupted gene was replaced by a hygromycin-resistance marker gene by in vivo homologous recombination. The deletion was performed into a BY4742 strain (AD5) complemented with a rescue plasmid (pSBTN-AE68) expressing the ORF ylr243w from the ADH1 promoter. The hygromycin gene was amplified from the plasmid pAG32 using the primers oAM29 (5′-CTT AAC AAG TAC AAA TAG AGT AAT CAG CAT TGG AAA ATC AAT ACA GCT GAA GCT TCG TAC GC-3′) and oAM30 (5′-CTT TTT ATA TGA ATC AAG CGT ACA TAA TTT TCT CTA TAA GCA TAG GCC ACT AGT GGA TCT G- 3′). The resulting DNA fragment contained 40 bp terminal ends homologous to flanking regions containing the respective translation start and stop sites of ylr243w. Cells were selected after transformation on plates containing rich medium supplemented with 200 µg/mL of hygromycin. Three colonies from independent experiments were selected and shown by PCR amplification to contain the ∆ylr243w::HygroR allele correctly substituted at the ylr243w locus. tetR-GFP and tetO112 tagging chromosome for chromatid cohesion assays was previously described (Alonso et al., 2011).

Mutations into yGPN1, yGPN2 and yGPN3 (yGPN1E112K, yGPN1E112A, yGPN1I111A, yGPN1Q110A, yGPN2E112K, yGPN2E112A, yGPN2V111A, yGPN2Q110A, yGPN3E110K, yGPN3E110A, yGPN3I109A and yGPN3Q108A) were introduced using the three fragment-homologous recombination system.32 The lexA DNA-binding domain and VP16-activating domain of the hybrid transcription factor LexA-VP16 were amplified by PCR and fused to yGPN1, yGPN2, yGPN3 and yGPN1E112K, yGPN2E112K, yGPN3E110K (LexA-yGPN1, LexA-yGPN1E112K VP16-yGPN2, VP16-yGPN2E112K, VP16-yGPN3 and VP16-yGPN3E110K). The different yGPN gene combinations tested for two-hybrid interactions were co-expressed in the same plasmid under the control of the inducible bidirectional promoter pGAL1–10. All constructs and mutations were checked by DNA sequencing. Each vector was co-transformed in yeast with p8op-LacZ multicopy vector (Clontech) (Ura3, 2µ).

BY4741 isogenic derivative strain expressing yGPN1 C-terminally tagged with a tandem affinity purification (TAP)-tag was obtained from Openbiosystems.

Chromatid cohesion assays

Assays were performed as previously described.8 The control strain was AI06 and the yGPN3 mutated strain was pSBTN-AJ87.

Comparative modeling of yeast GPN proteins

Comparative models (targets) were built upon the protein template of dimeric PAB0955 crystal structure [PDB 1YRA11 using a semi-automated protocol (unpublished)]. Targets yGPN1, yGPN2 and yGPN3 and template were aligned using ClustalW.33 The alignment was manually refined using the INTERALIGN program34 in which insertions/deletions were adjusted to avoid secondary structure elements. In addition, the sequence alignment was adjusted so that all the conserved G-boxes found in GTPase families were aligned. Sequence identities between yGPN1, yGPN2 and yGPN3 with PAB0955 template are 21%, 21% and 18%, respectively. Deletion in solvent-exposed protein loops were constructed using sub-optimal loop alignments followed by a loop closure protocol.20 Sub-optimal alignment means that the exact position of a loop deletion is varied within a user-given range: usually +/− 3 residues. Short insertions (< 17 residues) were modeled using RAMP,35 whereas the very long insertion in yGPN1 was interactively modeled as described elsewhere.36 Cartesian positions of all atoms were energy-minimized as previously described.20 The quality of comparative models was evaluated using Procheck,37 Prosa,38 DFIRE,39 FRST40 and MOLPROBITY.41

yGPN1|yGPN2 and yGPN1|yGPN3 heterodimers were modeled by superimposing yGPN1 coordinates onto those of chain A of PAB0955, whereas yGPN2 and yGPN3 coordinates were superimposed onto those of chain B of PAB0955. The superposition was performed using three conserved β-strands of PAB0955: 18–21, 46–50 and 112–117. Side-chains of heterodimers were optimized using in-house programs,20 checked with the Xfit viewer,42 and the positions of atomic coordinates were refined using X-PLOR43 using the all atom force field Charmm22.44 The GDP molecules bound into dimeric PAB0955 were inserted into all yGPN models without further refinement. Buried surface area was computed using the buried program.45

The mutational energy cost for replacing Glu112 residue was performed by computing ΔΔEE→K = ΔEK - ΔEE,46 where ΔEK and ΔEE are the relative potential energies of the mutant Lys and WT Glu in an optimized protein environment of the crystal structure, respectively.21 The potential energy is the sum of vdw and Coulombic interactions. All the relevant energy parameters were taken from the Charmm22 all-atom force-field library. The double mutation (Glu→Lys) in yGPN1-yGPN3 heterodimer was computed in a similar way, except that both mutations were simultaneously optimized.

β-Galactosidase activity tests

The final yeast transformants were analyzed for the induced β-galactosidase activity. Fusion protein expression of LexA-yGPN1, VP16-yGPN2 and VP16-yGPN3 was driven under the pGAL inducible promoter. For activity quantification, the transformants were inoculated into 3 mL liquid medium, the cells harvested at an OD600 ranging from 0.8–1, washed in water, centrifuged and lysed by two freeze/thaw cycles. Cells were resuspended in 300 µL of Sarcozyl buffer [60 mM Na2HPO4, 40 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM KCL, 1 mM MgSO4, 0.06% (vol/vol) Sarcosyl (Fluka) and 2.6 mM DTE (1.4-Dithioerythritol Sigma) PH7.0] and gently agitated 30 min at 30°C. Ffity µl of samples were taken and 150 µl of Sarcosyl buffer supplemented with 0.25 mM MUG (Methylumbelliferone β-D-pyranoside Sigma) was added to quantify β-galactosidase activity. After a 30 sec incubation time at 37°C and determination of the cell density at 600 nm, 4-MU fluorescence was read using a 360 nm excitation filter and a 460 emission filter. Fluorescence and absorbance were measured using a Fluostar optima (BMG) spectrofluorimeter. One FU/sec/OD indicated in the graph corresponds to 2.3.103 molecules of MU/second/cell. β-Galactosidase values reported are representative of two independent transformants tested for each construction introduced in yeast.

Western blot

Cell disruption and protein extraction were performed as previously described (Alonso et al., 2001). A total of 10 or 20 µg of total proteins were loaded per wells onto a 4–12% Bis-Tris NuPAGE precast electrophoresis gel (Invitrogen). After migration, the proteins were transferred onto a PVDF membrane (Millipore). The blot was then probed with an anti-LexA (2–12, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1/200) or anti-VP16 antibody (14–5, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1/200). Signal was developed using the immobilon chemiluminescence kit from Millipore.

TAP-tagged GPN1 purification, SDS-PAGE, NanoLC-MS/MS analysis, MS/MS assignment and statistical procedures

For TAP-tagged protein purification and SDS-PAGE analysis, yeasts were grown in 2 L of YPD liquid medium until an OD at 600 nm of 0.8 was reached. For in vivo formaldehyde cross-linking, two different concentrations of formaldehyde (0.15% and 0.2%) were directly added to the yeast cell culture, and cells were incubated at 30°C for 10 min. The cross-linking reaction was quenched for 20 min at 30°C by glycine with a final concentration of 0.125 M. After cross-linking, cells were collected and washed three times with 100 mL of ice-cold water. Pellets were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C until use. Cell pellets were lysed mechanically by means of steel beads using a mixer mill from Retsch in cold conditions. The purification of the TAP-tagged protein and its partners was done starting from cell lysates containing about 40 µg/ml total proteins. The purification was performed as described by Rigaut et al.47 in the presence of benzonase (25 U/mL) and without EDTA. For the final elution step, proteins retained on the calmodulin beads were eluted by addition of 70 µL of lithium-dodecyl-sulfate solution (Invitrogen). After 5 min incubation at 95°C, the whole sample was resolved by SDS-PAGE onto a 4–12% bis-TRIS NuPage gel (Invitrogen) with 3-(N-morpholino) propanesulfonic acid buffer (Invitrogen) as running buffer, but with a short migration time. The whole protein content from each lane was excised as a single polyacrylamide band, destained with water, treated and proteolyzed with trypsin as described previously.48

For nanoLC-MS/MS analysis, NanoLC-MS/MS experiments were performed on a LTQ-Orbitrap XL hybrid mass spectrometer (ThermoFisher) coupled to an UltiMate 3000 nano-LC system (Dionex-LC Packings) essentially as described in reference 49.

For MS/MS assignment, peak lists were generated with the MASCOT DAEMON software (version 2.2.2) from Matrix Science using the extract_msn.exe data import filter (ThermoFisher) from the Xcalibur FT package (version 2.0.7) from ThermoFisher. Data import filter options were set at: 400 (minimum mass), 5,000 (maximum mass), 0 (grouping tolerance), 0 (intermediate scans) and 1,000 (threshold). MS/MS assignments were performed using the MASCOT search engine (version 2.2.2, Matrix Science) against a local database constructed with the S. cerevisiae protein sequences from the Saccharomyces Genome Database (SGD release 20100105) available at www.downloads.yeastgenome.org. This database release comprises 5,885 protein sequences, totaling 2,916,234 amino acids. Searches for trypsic peptides were performed with the following parameters: a mass tolerance of 5 ppm on the parent ion and 0.5 Da on the MS/MS, static modifications of carbamidomethylated Cys (+57.0215) and dynamic modification of oxidized Met (+15.9949). The maximum number of missed cleavages for trypsin was set at 2. All peptide matches with a peptide score above its peptidic identity threshold set at p < 0.05 and rank 1 were filtered by the IRMa 1.23 software.50

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Kim Nasmyth (Oxford University) for generously providing plasmids (p306tetO2 × 112 and p128tetR-GFP). We gratefully acknowledge our colleagues (all from iBEB, SBTN): Alexia Maignot, Maxime Rodriguez and Emeline Lepitre for construction of plasmids and β-galactosidase activity tests, Anne Helène Davin for her assistance in TAP-tag experience, Christine Almunia for helpful discussion, Elisabeth Darrouzet for critical review of the manuscript and Eric Quéméneur for constant support. We thank the Commissariat à l’Energie Atomique et aux Energies Alternatives and the Agence Nationale de la Recherche for financial support (ANR-06-JCJC-0148).

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cc/article/23367

References

- 1.Nasmyth K. Cohesin: a catenase with separate entry and exit gates? Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:1170–7. doi: 10.1038/ncb2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ocampo-Hafalla MT, Uhlmann F. Cohesin loading and sliding. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:685–91. doi: 10.1242/jcs.073866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Skibbens RV. Establishment of sister chromatid cohesion. Curr Biol. 2009;19:R1126–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.10.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sjögren C, Nasmyth K. Sister chromatid cohesion is required for postreplicative double-strand break repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr Biol. 2001;11:991–5. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00271-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dorsett D. Gene regulation: the cohesin ring connects developmental highways. Curr Biol. 2010;20:R886–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohlsson R. Gene expression: The coherent Mediator. Nature. 2010;467:406–7. doi: 10.1038/467406a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parelho V, Hadjur S, Spivakov M, Leleu M, Sauer S, Gregson HC, et al. Cohesins functionally associate with CTCF on mammalian chromosome arms. Cell. 2008;132:422–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alonso B, Chaussinand G, Armengaud J, Godon C. A role for GPN-loop GTPase yGPN1 in sister chromatid cohesion. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:1828–37. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.11.15763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ben-Aroya S, Coombes C, Kwok T, O’Donnell KA, Boeke JD, Hieter P. Toward a comprehensive temperature-sensitive mutant repository of the essential genes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell. 2008;30:248–58. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matte-Tailliez O, Zivanovic Y, Forterre P. Mining archaeal proteomes for eukaryotic proteins with novel functions: the PACE case. Trends Genet. 2000;16:533–6. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(00)02137-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gras S, Chaumont V, Fernandez B, Carpentier P, Charrier-Savournin F, Schmitt S, et al. Structural insights into a new homodimeric self-activated GTPase family. EMBO Rep. 2007;8:569–75. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leipe DD, Koonin EV, Aravind L. Evolution and classification of P-loop kinases and related proteins. J Mol Biol. 2003;333:781–815. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leipe DD, Wolf YI, Koonin EV, Aravind L. Classification and evolution of P-loop GTPases and related ATPases. J Mol Biol. 2002;317:41–72. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giaever G, Chu AM, Ni L, Connelly C, Riles L, Véronneau S, et al. Functional profiling of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome. Nature. 2002;418:387–91. doi: 10.1038/nature00935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boulon S, Pradet-Balade B, Verheggen C, Molle D, Boireau S, Georgieva M, et al. HSP90 and its R2TP/Prefoldin-like cochaperone are involved in the cytoplasmic assembly of RNA polymerase II. Mol Cell. 2010;39:912–24. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uetz P, Giot L, Cagney G, Mansfield TA, Judson RS, Knight JR, et al. A comprehensive analysis of protein-protein interactions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature. 2000;403:623–7. doi: 10.1038/35001009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Staresincic L, Walker J, Dirac-Svejstrup AB, Mitter R, Svejstrup JQ. GTP-dependent binding and nuclear transport of RNA polymerase II by Npa3 protein. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:35553–61. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.286161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berman HM, Bhat TN, Bourne PE, Feng Z, Gilliland G, Weissig H, et al. The Protein Data Bank and the challenge of structural genomics. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7(Suppl):957–9. doi: 10.1038/80734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gras S, Fernandez B, Chaumont V, Carpentier P, Armengaud J, Housset D. Expression, purification, crystallization and preliminary crystallographic analysis of the PAB0955 gene product. Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun. 2005;61:208–11. doi: 10.1107/S1744309105000035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen SW, Pellequer JL. Identification of functionally important residues in proteins using comparative models. Curr Med Chem. 2004;11:595–605. doi: 10.2174/0929867043455891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pellequer J-L, Chen SW, Saboulard D, Delcourt M, Négrier C, Plantier JL. Functional mapping of factor VIII C2 domain. Thromb Haemost. 2011;106:121–31. doi: 10.1160/TH10-09-0572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koonin EV. Orthologs, paralogs, and evolutionary genomics. Annu Rev Genet. 2005;39:309–38. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.39.073003.114725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Forget D, Lacombe AA, Cloutier P, Al-Khoury R, Bouchard A, Lavallée-Adam M, et al. The protein interaction network of the human transcription machinery reveals a role for the conserved GTPase RPAP4/GPN1 and microtubule assembly in nuclear import and biogenesis of RNA polymerase II. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2010;9:2827–39. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M110.003616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murzin AG, Brenner SE, Hubbard T, Chothia C. SCOP: a structural classification of proteins database for the investigation of sequences and structures. J Mol Biol. 1995;247:536–40. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80134-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu W, Park KT, Holyoak T, Lutkenhaus J. Determination of the structure of the MinD-ATP complex reveals the orientation of MinD on the membrane and the relative location of the binding sites for MinE and MinC. Mol Microbiol. 2011;79:1515–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07536.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu Z, Saez C, Lutkenhaus J. Recruitment of MinC, an inhibitor of Z-ring formation, to the membrane in Escherichia coli: role of MinD and MinE. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:196–203. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.1.196-203.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carré C, Shiekhattar R. Human GTPases associate with RNA polymerase II to mediate its nuclear import. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:3953–62. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05442-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jeronimo C, Langelier MF, Zeghouf M, Cojocaru M, Bergeron D, Baali D, et al. RPAP1, a novel human RNA polymerase II-associated protein affinity purified with recombinant wild-type and mutated polymerase subunits. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:7043–58. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.16.7043-7058.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lembo F, Pero R, Angrisano T, Vitiello C, Iuliano R, Bruni CB, et al. MBDin, a novel MBD2-interacting protein, relieves MBD2 repression potential and reactivates transcription from methylated promoters. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:1656–65. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.5.1656-1665.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Calera MR, Zamora-Ramos C, Araiza-Villanueva MG, Moreno-Aguilar CA, Peña-Gómez SG, Castellanos-Terán F, et al. Parcs/Gpn3 is required for the nuclear accumulation of RNA polymerase II. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813:1708–16. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kagey MH, Newman JJ, Bilodeau S, Zhan Y, Orlando DA, van Berkum NL, et al. Mediator and cohesin connect gene expression and chromatin architecture. Nature. 2010;467:430–5. doi: 10.1038/nature09380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kitagawa K, Abdulle R. In vivo site-directed mutagenesis of yeast plasmids using a three-fragment homologous recombination system. Biotechniques. 2002;33:288–, 290, 292 passim. doi: 10.2144/02332bm07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–80. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pible O, Imbert G, Pellequer J-L. INTERALIGN: interactive alignment editor for distantly related protein sequences. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3166–7. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Samudrala R, Moult J. An all-atom distance-dependent conditional probability discriminatory function for protein structure prediction. J Mol Biol. 1998;275:895–916. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pellequer J-L, Gale AJ, Griffin JH, Getzoff ED. Homology modeling of Factor Va, a cofactor of the prothrombinase complex. PS (Wash DC) 1998;7(suppl. 1):159. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laskowski RA, MacArthur MW, Moss DS, Thornton JM. PROCHECK: A program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J Appl Cryst. 1993;26:283–91. doi: 10.1107/S0021889892009944. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sippl MJ. Recognition of errors in three-dimensional structures of proteins. Proteins. 1993;17:355–62. doi: 10.1002/prot.340170404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang Y, Skolnick J. Scoring function for automated assessment of protein structure template quality. Proteins. 2004;57:702–10. doi: 10.1002/prot.20264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tosatto SC. The victor/FRST function for model quality estimation. J Comput Biol. 2005;12:1316–27. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2005.12.1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen VB, Arendall WB, 3rd, Headd JJ, Keedy DA, Immormino RM, Kapral GJ, et al. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McRee DE. XtalView/Xfit--A versatile program for manipulating atomic coordinates and electron density. J Struct Biol. 1999;125:156–65. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1999.4094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brünger AT. X-PLOR, version 3.1. A system for X-ray crystallography and NMR. New Haven, (CT): Yale University Press, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 44.MacKerell AD, Bashford D, Bellott M, Dunbrack RL, Jr., Evanseck JD, Field MJ, et al. All-atom empirical potential for molecular modeling and dynamics studies of proteins. J Phys Chem B. 1998;102:3586–616. doi: 10.1021/jp973084f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sanner MF, Olson AJ, Spehner J-C. Reduced surface: an efficient way to compute molecular surfaces. Biopolymers. 1996;38:305–20. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(199603)38:3<305::AID-BIP4>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pellequer J-L. Chen S-wW. Multi-template approach to modeling engineered disulfide bonds. Proteins. Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics. 2006;65:192–202. doi: 10.1002/prot.21059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rigaut G, Shevchenko A, Rutz B, Wilm M, Mann M, Séraphin B. A generic protein purification method for protein complex characterization and proteome exploration. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:1030–2. doi: 10.1038/13732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.de Groot A, Dulermo R, Ortet P, Blanchard L, Guérin P, Fernandez B, et al. Alliance of proteomics and genomics to unravel the specificities of Sahara bacterium Deinococcus deserti. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000434. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Clair G, Roussi S, Armengaud J, Duport C. Expanding the known repertoire of virulence factors produced by Bacillus cereus through early secretome profiling in three redox conditions. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2010;9:1486–98. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M000027-MCP201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dupierris V, Masselon C, Court M, Kieffer-Jaquinod S, Bruley C. A toolbox for validation of mass spectrometry peptides identification and generation of database: IRMa. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1980–1. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J Mol Graph. 1996;14:33–8, 27-8. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kraulis PJ. MOLSCRIPT: a program to produce both detailed and schematic plots of protein structures. J Appl Cryst. 1991;24:946–50. doi: 10.1107/S0021889891004399. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Merritt EA, Bacon DJ. Raster3D: photorealistic molecular graphics. Methods Enzymol. 1997;277:505–24. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)77028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang Y, Zhou Y. Specific interactions for ab initio folding of protein terminal regions with secondary structures. Proteins. 2008;72:793–803. doi: 10.1002/prot.21968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Davis IW, Leaver-Fay A, Chen VB, Block JN, Kapral GJ, Wang X, et al. MolProbity: all-atom contacts and structure validation for proteins and nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(Web Server issue):W375-83. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.