Abstract

Kutajarista is an Ayurvedic fermented herbal formulation prescribed for gastrointestinal disorders. This herbal formulation undergoes a gradual fermentative process and takes around 2 months for production. In this study, microbial composition at initial stages of fermentation of Kutajarista was assessed by culture independent 16S rRNA gene clone library approach. Physicochemical changes were also compared at these stages of fermentation. High performance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry analysis showed that Gallic acid, Ellagic acid, and its derivatives were the major chemical constituents recovered in this process. At 0 day of fermentation, Lactobacillus sp., Acinetobacter sp., Alcaligenes sp., and Methylobacterium sp. were recovered, but were not detected at 8 day of fermentation. Initially, microbial diversity increased after 8 days of fermentation with 11 operational taxonomic units (OTUs), which further decreased to 3 OTUs at 30 day of fermentation. Aeromonas sp., Pseudomonas sp., and Klebsiella sp. dominated till 30 day of fermentation. Predominance of γ- Proteobacteria and presence of gallolyl derivatives at the saturation stage of fermentation implies tannin degrading potential of these microbes. This is the first study to highlight the microbial role in an Ayurvedic herbal product fermentation.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12088-012-0325-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Ayurveda, Kutajarista, Microbial diversity, Fermentation

Introduction

Kutajarista is a polyherbal Ayurvedic formulation prepared traditionally by the process of alcoholic fermentation. It is widely known for its role in the treatment of chronic diseases like amoebic dysentery, piles, and intestinal parasite infestation [9, 29]. In Ayurvedic formulation, fermentation of asava (fermented decoctions) and arishta (fermented infusions) is brought by slow decomposition process of organic compounds and liquefaction of mucilaginous substrates like cellulose and pectin. This slow process also helps in extraction of wide range of active ingredients from herbal formulations [32].The process of fermentation is mainly initiated by the addition of dhataki flowers (Woodfordia fruticosa kurz) which act as source of yeast for fermentation [2, 21].

Recently, there has been increased interest in standardisation of these herbal preparations to ensure consistent supply of high quality of Ayurvedic products [16, 30].Chemical changes during fermentation of herbal medicines like Arjunarishta [16, 30], Abhayarishta [17], Kutajarista, and Jirakadyarishta [18] have been studied in detail. These studies have also led to the identification of chemical markers which can be a characteristic fingerprint of plant or constituents of these herbal preparations. Like other alcoholic fermentation processes, Ayurvedic fermentation is also driven by yeast. However, there are very limited or no studies which highlight the microbial composition in these fermentation processes. One report dates back to 1977, where an attempt was made to isolate fermenting microorganisms from asava and arishta [2]. Identification and characterization of an appropriate starter culture can help in driving the fermentation of these herbal formulations towards desirable functional characteristics like consistent industrial quality and improvement in extraction of drug molecules in aqueous milieu [29].

Comprehensive microbiological characterization of these herbal formulations has not been carried out till date. Culture based approaches are laborious, have low throughput, and may miss bacterial species with unique or unknown growth requirements [24]. Alternatively, 16S rRNA gene based typing provides reliable and rapid glimpse of microbial consortia involved during these fermentation processes [1, 20].

In this study, we have employed a culture independent approach by preparing 16S rRNA gene clone library, in order to understand the microbial composition during the process of fermentation of Kutajarista. To the best of our knowledge this is the first study of this kind.

Materials and Methods

Collection and Quality Assessment of Fermented Samples

All samples were collected from Ayurvedic Rasashala, an Ayurvedic company located in Pune, India. Samples were collected at different time points (0, 8, and 30 days) in a sterile container. Sampling period was designed logically in order to assess the microbial and major chemical dynamics in the beginning (0-day), active phase of fermentation (8-day), and at the stage of saturation (after 30-days). Physicochemical parameters such as pH, specific gravity, titratable acidity, sugar content, and alcohol percentage of the samples were determined by quality control department of the company as per Central Council for Research in Ayurvedic and Siddha standards [9, 34]. For microbial community DNA isolation, samples were stored at −80 °C.

DNA Extraction, Clone Library Preparation and Sequencing

Total DNA was extracted from 1 ml of samples using a QIAmp DNA Stool kit (Qiagen, USA) according to manufacturer’s guidelines with slight modifications. 1) Samples were given Proteinase K treatment for overnight at 55 °C. 2) After buffer AL treatment, equal volume of phenol: chloroform: isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) was added and then precipitated by isopropanol. The 16S rRNA gene was amplified from total DNA using universal bacterial primers 536F (5′-GTCCCAGCAGCCGCGGTRATA-3′) and 1488R (5′-CGGTTACCTTGTTACGACTTCACC-3′), cloned and sequenced as described previously [11].

Phylogenetic and Microbial Diversity Analysis

16S rRNA gene sequences retrieved from respective clones were assembled and edited using ChromasPro version 1.5. All sequences were checked for chimeric artifacts using Mallard and predicted chimeras were further analysed by Pintail and Bellerophon. Multiple sequence alignments were performed using ClustalW version 1.8 and were manually edited using DAMBE for unambiguous alignment. 16S rRNA gene sequence subsets were selected based on initial results and then subjected to further phylogenetic analysis using neighbour joining method in DNADIST of PHYLIP (version 3.61). Operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were determined using DOTUR. Total 1,000 bootstrap replicates were generated and a consensus tree was made. Phylogenetic dendograms generated were further viewed by using MEGA version 4.0. Representative sequences were assigned GenBank accession numbers (GenBankID: HQ875575 to HQ875614).

Diversity Indices and Rarefaction Analysis

Good’s coverage was estimated using the formula [1−(n/N)] × 100, where N denotes the library size and n is the number of OTUs with single clone sequence. Diversity indices were calculated using Shannon’s evenness index for general diversity (H’ = −Upi x ln pi) and the Simpson dominance index (SI’ = n (n−1)/N (N−1)) [33]. Rarefaction analysis was carried out using 16S rRNA gene sequences retrieved from the DOTUR analysis and rarefaction curve was generated to compare the saturation of OTUs within the selected sample size.

Chemical Analysis of Samples

To assess chemical changes during the process of fermentation, non targeted chemical profiling was carried out on HPLC–MS according to the previously published methodology [9]. Briefly, the alkaloid fraction was subjected to HPLC–MS using solvent system of acetonitrile: water (both containing 0.1 % acetic acid) at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. The MS experiment setup and data acquisition were conducted using the Mass Lynx software v 4.0.

Results

Physicochemical Parameters of Samples Collected at Different Days of Fermentation

Physicochemical parameters were found to in accordance with the prescribed limits (Table 1). The pH of fermented samples changed from 4.24 to 3.96 during the period of 30 days, which is in line with previous work [9]. Decrease in sugar content and gradual increase in alcohol content implies active fermentation during this period (Table 1).

Table 1.

Physicochemical parameters of Kutajarista at 0, 8, and 30 days of fermentation

| S.No. | Sampling day | Specific gravity | Sugar content (%) | pH | Alcohol (%) | Acidity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 0 day | 2.2 | 31 | 4.24 | NPa | 0.3021 |

| 2 | 8 day | 1.07 | 24 | 3.62 | 8.01 | 0.5437 |

| 3 | 30 day | 1.04 | 22 | 3.96 | 11 | 0.4301 |

aNot present

Bacterial Dynamics During the Fermentation

16S rRNA gene library was constructed to analyse the change in composition of bacterial community during the fermentation at 0, 8, and 30 days.

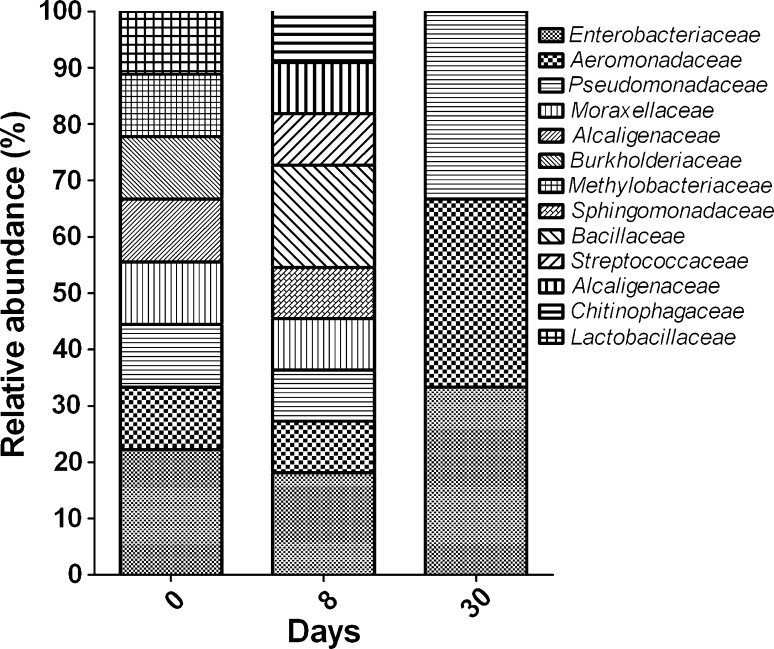

Approximately 232 clones were sequenced for partial 16S rRNA gene for all three time points of fermentation. At 0 day, 74 % of sequenced clones belonged to genus Aeromonas, followed by Pseudomonas sp. and Klebsiella sp. We also found the presence of Lactobacillus sp. (Clone KA0D 7) at day of fermentation, which showed its close homology with an Lactobacillus isolate (Fig. 1) reported from distilled shochu [6]. The other genera detected by clone library (Table 2) at 0 day include Acinetobacter sp, Alcaligenes sp., Cupriavidus sp., and Methylobacterium sp. After 8 days, significant changes in the bacterial community were observed (Fig. 2). A total of 11 OTUs were obtained, which were predominated by Aeromonas (67 % of the total sequences). Pseudomonas sp. and Bacillus sp. covered around 10 % of the sequenced clones, followed by Klebsiella sp. and Streptococcus sp. At the saturation point of 30 day, three OTUs were found. Aeromonas sp. constituted 80 % of the sequences followed by Pseudomonas sp. and Klebsiella sp. with 13 and 6 % of the sequences respectively (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic tree of bacterial OTUs recovered at 0, 8, and 30 day of fermentation. Clones with prefix KA 0D, KA 8D, and KA 30D denotes sequenced clones at 0, 8, and 30 days of fermentation respectively

Table 2.

OTUs found in 16S rRNA gene library at 0, 8, and 30 days of fermentation

| OTU (number of clones) | Nearest neighbour (accession number) | Similarity (%) | Phylogenetic group |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 day | |||

| KA0D 7 (3) | Lactobacillus farraginis (AB262731) | 99.795 | Firmicutes |

| KA0D172 (4) | Klebsiella oxytoca (AB262731) | 99.893 | Proteobacteria |

| KA0D 2 (2) | Klebsiella pneumoniae (AB262731) | 97.97 | Proteobacteria |

| KA0D 54 (67) | Aeromonas punctata (AB262731) | 99.598 | Proteobacteria |

| KA0D 10 (9) | Pseudomonas mendocina (AB262731) | 99.576 | Proteobacteria |

| KA0D 111 (1) | Acinetobacter junii (AB262731) | 99.579 | Proteobacteria |

| KA0D 75 (2) | Alcaligenes faecalis (AB262731) | 99.778 | Proteobacteria |

| KA0D 107 (1) | Cupriavidus metallidurans (AB262731) | 100 | Proteobacteria |

| KA0D 93 (1) | Methylobacterium adhaesivum (AB262731) | 98.703 | Proteobacteria |

| 8 day | |||

| 8d1610f (1) | Novosphingobium tardaugens (AB070237) | 97.484 | Proteobacteria |

| 8d1656f (4) | Bacillus fusiformis (AB271743) | 99.83 | Firmicutes |

| 8d1652f (1) | Bacillus coagulans (D16267) | 99.515 | Firmicutes |

| 8d1630f (1) | Streptococcus sanguinis (AY281085) | 99.7 | Firmicutes |

| 8d1617f (1) | Achromobacter xylosoxidans (Y14908) | 99.543 | Proteobacteria |

| 8d1636f (5) | Pseudomonas argentinensis (AY691188) | 99.814 | Proteobacteria |

| 8d1640f (35) | Aeromonas punctata (X60408) | 99.834 | Proteobacteria |

| 8d165f (1) | Klebsiella oxytoca (AB004754) | 100 | Proteobacteria |

| 8D16_39 (1) | Shigella flexneri (X96963) | 99.868 | Proteobacteria |

| 8D16_40 (1) | Enhydrobacter aerosaccus (AJ550856) | 99.406 | Proteobacteria |

| 8d1671f (1) | Sediminibacterium salmoneum (EF407879) | 98.827 | Bacteroidetes |

| 30 day | |||

| 30D16_18 (72) | Aeromonas media (X74679) | 100 | Proteobacteria |

| 30D16_84 (6) | Klebsiella oxytoca (AB004754) | 99.889 | Proteobacteria |

| 30D16E_8 (12) | Pseudomonas mendocina (Z76664) | 99.332 | Proteobacteria |

Fig. 2.

Relative abundance of bacterial families in samples at 0, 8, and 30 days of fermentation

Statistical Analysis

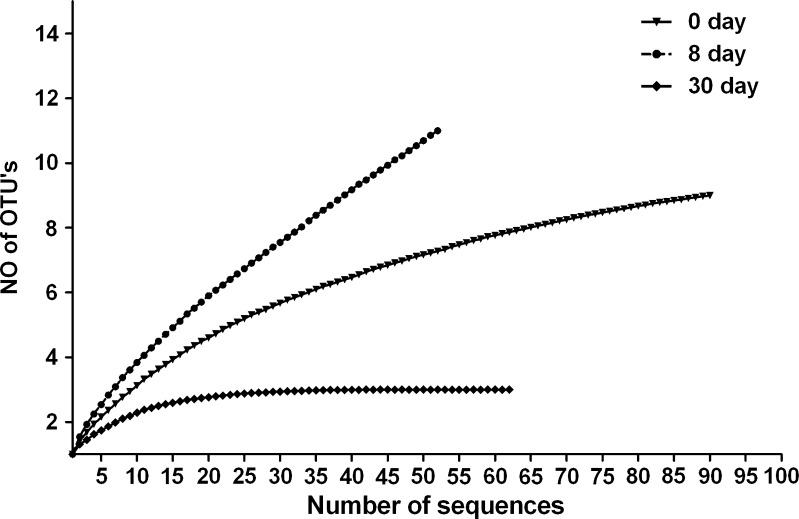

Good’s coverage of sequences at 0, 8, and 30 day was 97, 84, and 100 %, respectively, which suggests that there is adequate library coverage for all the days of fermentation and there is only 3, 16, and 0 %, chances of finding a new clone, respectively, to fall in these libraries. Shannon’s general diversity indices (represents evenness), for 0, 8, and 30 days were 1.02, 1.29, and 0.62, respectively, which suggest that diversity first increases from 0 to 8 day and then decreases from 8 to 30 days of fermentation. Simpson’s dominance indices for 0, 8, and 30 days were 0.56, 0.46, and 0.65, respectively, which imply a decrease in species evenness at 8 day of fermentation. The rarefaction curve (Fig. 3) indicates that diversity was covered with good level of confidence.

Fig. 3.

Rarefaction curves for bacterial OTUs recovered at different time point of fermentation i.e. 0, 8, and 30 days

Major Changes in Chemical Profile During Fermentation

At 0 day of fermentation the peak of m/z 169 and appearing at retention time (RT) of 6.50, was characteristic for Gallic acid (online resource 1), in concordance to our previous study. Eight day sample indicated presence of Ellagic acid (m/z 197) at RT 30.38 min in addition to Gallic acid at RT 7.67. After 30 days of fermentation we have also found gallolyl derivatives (m/z 169) with retention time of 13.28 and Ellagic acid at RT 30.82.

Discussion

The objective of this study was to identify the microbial composition during the course of fermentation of Kutajarista. We found the percentage of alcohol, specific gravity, and pH in these samples are in concordance to our earlier study [9]. According to one independent study, Ashvagandharishta and Aravindasava also have mean alcohol percentage between 9 and 11 % and a pH range from 3.6 to 3.8 [34].

Results obtained from 16S rRNA gene clone library revealed slight different microbial composition in comparison to other fermentation processes or products; this can be attributed to the difference in the initial starting ingredient of the fermentation [20, 24]. In Ayurvedic medicines, asavas and arishta are prepared by different parts of the medicinal plant, such as roots, leaves or barks, which are cut into pieces and powdered or prepared by decoction [21].

The presence of less abundant phyla in clone library like Acinetobacter sp., Alcaligenes sp., Cuprividus sp., and Methylobacterium sp. at initiation of fermentation (0 day) of Kutajarista, signify their ubiquitous presence in herbal sources. Similar to other fermentation processes, Lactobacillus sp. was also found in initial days of fermentation, which can be exploited for its beneficial activity. For instance, Lactobacillus sp. isolated from alcoholic fermentation of raffia wine has been examined for its immune stimulation activity in mouse model [7]. Previously, we have also reported probiotic attributes of Lactobacillus plantarum isolated from similar sources [15]. At 8 day of fermentation, presence of Streptococcus and Bacillus spp., indicated vigorous stage of fermentation, and reported to have pectinlolytic activity [12, 26].

Previously, role of γ-Proteobacteria have been associated with various alcoholic fermentation processes, for example, Aeromonas sp. has been reported in the waste water of wine [27], Pseudomonas sp. from brewery granules [14], and Klebsiella sp. in ethanol production from lignocelluloses biomass [25]. Their persistence could also be because of their high cytosolic alcohol dehydrogenase activity, which helps in alcoholic fermentation [13, 23]. These species are also known to have high potential to utilize complex carbohydrates and amino acids to produce alcohol and organic acids [19, 25]. The presence of these species in Kutajarista fermentation may further imply their possible role in rapid fermentation of sugar and acidification during this observed period. Chemical analysis revealed this acidification process by the presence of Gallic acid, at initial stage, which was later transformed into ellagic acid and gallolyl derivatives.

Gallic acid and its derivatives are polyhydric esterified form of tannic acids, which are degraded by microbial tannase or tannin acyl hydrolase. Among microbial species recovered in our study, Klebsiella sp. and Pseudomonas sp. have been reported for their potential to degrade tannic acid to gallic acid [4], [8]. Streptococcus sp. [22], Bacillus sp. [28], and some species of Enterobacteriaceae family [31] were also found to be tolerant to higher concentration of tannins. A report on microbial diversity analysis for tannin bioremediation processes also revealed the presence of Pseudomonas sp. with high tannin degrading activity [5]. In general, biodegradation of tannin is associated with hydroxylation and production of aliphatic intermediates which can subsequently form metabolites of krebs cycle [5]. Specific modifications or transformation of these biodegradation mechanisms depend on the syntrophic association between different group of microbial species involved [4]. γ-Proteobacteria have also been shown to be predominantly associated with efficient tannin or cellulose degradation into non toxic chemicals [3, 10, 31]. We have also isolated Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains, involved in alcoholic fermentation from these sources (unpublished data). Therefore, along with Saccharomyces cerevisiae, these consortia of microorganisms produce an array of enzymes capable of degrading chemical linkages in plant polymers for alcohol production and extraction of active drug in aqueous milieu.

In conclusion, this is the first study to highlight the dynamics of microbes and its potential role at initial days of fermentation of Kutajarista. Exhaustive sampling and further in depth chemical analysis from other Ayurvedic natural products, may further lead to isolation and industrial exploitation of microbes or consortia of microbes.

Electronic supplementary material

Online resource 1 HPLC–MS profile of the alkaloid fraction of the samples taken at different days of fermentation. (JPEG 50 kb)

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr. Prakash N kale and Mrs S bhosale, Ayurveda Rasashala for helping in physicochemical analysis of the Kutajarista. We thank Ms. Tricia Goulding (University of California) and Dr. O.P. Sharma (National Centre for Cell Science) for proof reading of the manuscript and suggestions. We also thank CSIR (Council of Scientific and Industrial Research) India for providing research fellowship to Himanshu Kumar.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Himanshu Kumar, Email: himanshu@nccs.res.in.

Prashant Kumar Pandey, Email: prashantkpandey@gmail.com.

V. V. Doiphode, Email: doiphode2007@yahoo.com

Sanjay Vir, Email: virsanjay@indiatimes.com.

K. K. Bhutani, Email: kkbhutani@niper.ac.in

M. S. Patole, Email: patole@nccs.res.in

Y. S. Shouche, Phone: +91-20-25708050, FAX: +91-20-25692259, Email: yogesh@nccs.res.in

References

- 1.Abriouel H, Benomar N, Lucas R, Galvez A. Culture-independent study of the diversity of microbial populations in brines during fermentation of naturally-fermented Alorena green table olives. Int J Food Microbiol. 2011;144(3):487–496. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alam M, Krishna DDV, Varadarajan TV, Sarma PSN, Purushothaman KK. Ashavas and arishtas—identification of a fermenting organism. J Res Educ Indian Med. 1977;12(4):38–43. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anand AAP, Vennison SJ, Sankar SG, Prabhu DIG, Vasan PT, Raghuraman T, Geoffrey CJ, Vendan SE. Isolation and characterization of bacteria from the gut of bombyx mori that degrade cellulose, xylan, pectin and starch and their impact on digestion. J Insect Sci. 2009;10:1–20. doi: 10.1673/031.010.10701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhat TK, Singh B, Sharma OP. Microbial degradation of tannins — a current perspective. Biodegradation. 1998;9(5):343–357. doi: 10.1023/A:1008397506963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chowdhury SP, Khanna S, Verma SC, Tripathi AK. Molecular diversity of tannic acid degrading bacteria isolated from tannery soil. J Appl Microbiol. 2004;97(6):1210–1219. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Endo A, Okada S. Lactobacillus farraginis sp. nov. and Lactobacillus parafarraginis sp. nov., heterofermentative lactobacilli isolated from a compost of distilled shochu residue. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2007;57(Pt 4):708–712. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64618-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flore TN, Francois ZN, Felicite TM. Immune system stimulation in rats by Lactobacillus sp. isolates from Raffia wine (Raphia vinifera) Cell Immunol. 2010;260(2):63–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Franco AR, Calheiros CS, Pacheco CC, De Marco P, Manaia CM, Castro PM. Isolation and characterization of polymeric galloyl-ester-degrading bacteria from a tannery discharge place. Microb Ecol. 2005;50(4):550–556. doi: 10.1007/s00248-005-5020-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garg S, Bhutani KK. Chromatographic analysis of Kutajarista—an ayurvedic polyherbal formulation. Phytochem Anal. 2008;19(4):323–328. doi: 10.1002/pca.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goel G, Puniya AK, Aguilar CN, Singh K. Interaction of gut microflora with tannins in feeds. Naturwissenschaften. 2005;92(11):497–503. doi: 10.1007/s00114-005-0040-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gupta AK, Nayduch D, Verma P, Shah B, Ghate HV, Patole MS, Shouche YS. Phylogenetic characterization of bacteria in the gut of house flies (Musca domestica L.) FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2012;79(3):581–593. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2011.01248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gupta S, Abu-Ghannam N. Probiotic fermentation of plant based products: possibilities and opportunities. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2012;52(2):183–199. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2010.499779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ingram LO, Aldrich HC, Borges AC, Causey TB, Martinez A, Morales F, Saleh A, Underwood SA, Yomano LP, York SW, et al. Enteric bacterial catalysts for fuel ethanol production. Biotechnol Prog. 1999;15(5):855–866. doi: 10.1021/bp9901062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keyser M, Britz TJ, Witthuhn RC. Fingerprinting and identification of bacteria present in UASB granules used to treat winery, brewery, distillery or peach-lye canning wastewater. S Afr J Enol Vitic. 2007;28(1):69–79. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar H, Rangrez AY, Dayananda KM, Atre AN, Patole MS, Shouche YS. Lactobacillus plantarum (VR1) isolated from an ayurvedic medicine (Kutajarista) ameliorates in vitro cellular damage caused by Aeromonas veronii. BMC Microbiol. 2011;11:152. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lal UR, Tripathi SM, Jachak SM, Bhutani KK, Singh IP. HPLC analysis and standardization of Arjunarishta - an ayurvedic cardioprotective formulation. Sci Pharm. 2009;77(3):605–616. doi: 10.3797/scipharm.0906-03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lal UR, Tripathi SM, Jachak SM, Bhutani KK, Singh IP. Chemical changes during fermentation of Abhayarishta and its standardization by HPLC–DAD. Nat Prod Commun. 2010;5(4):575–579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lal UR, Tripathi SM, Jachak SM, Bhutani KK, Singh IP. RP-HPLC analysis of Jirakadyarishta and chemical changes during fermentation. Nat Prod Commun. 2010;5(11):1767–1770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee C, Kim J, Hwang K, Hwang S. Fermentation and growth kinetic study of Aeromonas caviae under anaerobic conditions. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009;83(4):767–773. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-1983-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsui H, Tsuchiya R, Isobe Y, Narita M (2011) Analysis of bacterial community structure in Saba-Narezushi (Narezushi of Mackerel) by 16S rRNA gene clone library. J Food Sci Technol :1–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Mishra AK. Asava and aristha: an ayurvedic medicine — an overview. International J Pharm Biol Arch. 2010;1(1):24–30. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nelson KE, Thonney ML, Woolston TK, Zinder SH, Pell AN. Phenotypic and phylogenetic characterization of ruminal tannin-tolerant bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64(10):3824–3830. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.10.3824-3830.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nosova T, Jousimies-Somer H, Kaihovaara P, Jokelainen K, Heine R, Salaspuro M. Characteristics of alcohol dehydrogenases of certain aerobic bacteria representing human colonic flora. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1997;21(3):489–494. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1997.tb03795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oguntoyinbo FA, Tourlomousis P, Gasson MJ, Narbad A. Analysis of bacterial communities of traditional fermented West African cereal foods using culture independent methods. Int J Food Microbiol. 2010;145(1):205–210. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohta K, Beall DS, Mejia JP, Shanmugam KT, Ingram LO. Metabolic engineering of Klebsiella oxytoca M5A1 for ethanol production from xylose and glucose. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57(10):2810–2815. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.10.2810-2815.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ouattara HG, Reverchon S, Niamke SL, Nasser W. Molecular identification and pectate lyase production by Bacillus strains involved in cocoa fermentation. Food Microbiol. 2011;28(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2010.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petruccioli M, Duarte JC, Federici F. High-rate aerobic treatment of winery wastewater using bioreactors with free and immobilized activated sludge. J Biosci Bioeng. 2000;90(4):381–386. doi: 10.1016/s1389-1723(01)80005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raghuwanshi S, Dutt K, Gupta P, Misra S, Saxena RK. Bacillus sphaericus: the highest bacterial tannase producer with potential for gallic acid synthesis. J Biosci Bioeng. 2011;111(6):635–640. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sekar S, Mariappan S. Traditionally fermented biomedicines, arishtas and asavas from Ayurveda. Indian J Tradit Knowl. 2008;7(4):548–556. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh H, Mishra SK, Pande M. Standardization of Arjunarishta formulation by TLC method. Int J Pharm Sci Rev Res. 2010;2(1):25–28. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith AH, Mackie RI. Effect of condensed tannins on bacterial diversity and metabolic activity in the rat gastrointestinal tract. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70(2):1104–1115. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.2.1104-1115.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sushruta M, Khale A. Asavarishtas through improved fermentation technology. Int J Pharma Sci Res. 2011;2(6):1421–1425. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wani AA, Surakasi VP, Siddharth J, Raghavan RG, Patole MS, Ranade D, Shouche YS. Molecular analyses of microbial diversity associated with the Lonar soda lake in India: an impact crater in a basalt area. Res Microbiol. 2006;157(10):928–937. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weerasooriya WMB, Liyanage JA, Pandya SS. Quantitative parameters of different brands of asava and arishta used in ayurvedic medicine: an assessment. Indian J Pharmacol. 2006;38(5):365. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.27710. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Online resource 1 HPLC–MS profile of the alkaloid fraction of the samples taken at different days of fermentation. (JPEG 50 kb)