Abstract

Objective

To investigate the status of diagnosis and treatment of primary breast cancer in Beijing, 2008.

Methods

All the patients who were diagnosed as primary breast cancer in Beijing in 2008 were enrolled in this study. Information of these patients, including the features of tumors, clinical diagnosis and treatment was collected, and filled in the well-designed questionnaire forms by trained surveyors. The missing data was partly complemented through telephone interviews.

Results

A total of 3473 Beijing citizens were diagnosed as primary breast cancer (25 patients with synchronal bilateral breast cancer) in Beijing, 2008. Of them 82.09% were symptomatic. 19.02% and 34.11% were diagnosed using fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) and core needle biopsy (CNB), respectively. 15.92% received sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) and 24.27% received breast conserving surgery (BCS). Among 476 cases with Her-2 positive, only 96 received anti-Her-2 therapy. We found that the standardization level varied in hospitals of different grades, with higher level in Grade-III hospitals. Of note, some breast cancer patients received non-standard primary tumor therapy: 65.63% of the patients with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) received axillary lymph node dissection and 36.88% received chemotherapy; 25.89% of the patients underwent breast conserving surgery without margin status; 12.10% of the patients received chemotherapy less than 4 cycles.

Conclusion

Although most breast cancer patients received basic medical care, the mode of diagnosis and treatment should be improved and should be standardized in the future in Beijing.

Key words: Breast cancer, Diagnosis, Treatment, Nonstandard treatment

INTRODUCTION

Despite a recent decline in breast cancer mortality in the US, breast cancer is still the second leading incidence cancer in women in the world[1]. The annual age-standardized (world population) incidence rate of breast cancer was 37.8 per 100,000 in Beijing, 2007, with an annual 4.97% increasing from 1998 to 2007 according to the data from Beijing Cancer Registry.

A number of factors have been associated with the outcomes of the breast cancer. The most effective strategies are primary and secondary prevention. In addition, evidence-based standard diagnosis and treatment are critical for survival of breast cancer. Although evidence-based guidelines, such as NCCN and St Gallen consensus[2, 3] have been adopted in most developed countries, little is known about the current status of diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer in China.

With a population over 1.7 million, Beijing is one of the largest cities in the world. There are over 110 hospitals in Beijing, from 500-1000 beds large municipal hospitals (Grade III) to 200-500 beds district level hospital (Grade II). Approximately 3,000 new cases of breast cancer are diagnosed and treated in grade II and III hospitals each year in Beijing. To evaluate the current clinical practice in breast cancer, we obtained all medical information on the time of first visit hospital, stepwise examinations, different surgical treatment or chemotherapy or immunotherapy from 3,473 newly diagnosed breast cancers in Beijing, 2008.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Population

According to the data from Beijing Cancer Registry, 3473 Beijing citizens were diagnosed as primary breast cancer and received anti-cancer therapy from January 1 to December 31, 2008. In this study, 101 hospitals provided the basic and clinical data of these patients.

Data Collection

A questionnaire was approved by the panel of the breast cancer experts including epidemiologists and breast surgeons, and used in this study from March 1 to August 1, 2010. The data of the breast cancer patients were collected mainly from the inpatient medical records and partly from the outpatient medical records, and then filled in the questionnaire forms by trained surveyors from the medical record rooms of 101 hospitals in Beijing. If the patient was diagnosed and treated in more than one hospital, we adopt the data from the hospital where the patient received surgical treatment. Some information of outpatient treatment was collected through telephone interviews.

Evaluation Criteria

The strategies that met the criteria of (NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology) and the recommendation of 2007 St Gallen conference[2, 3], as well as advice of breast cancer experts in Beijing, were defined as standard diagnostic and therapeutic methods.

Quality Control

The survey questionnaire design, training of surveyors, data review, data collection and data analysis were all well-controlled. During peer review, the filled questionnaire forms were double-checked first by two surveyor and then re-checked by the monitor randomly. All the data were finally input using parallel double-entry method and checked with ACCESS 2003 version.

Statistical Analysis

The frequency and proportions of all collected variables were calculated using statistical software SPSS 13.0.

RESULTS

Characteristics General Date of the Patients

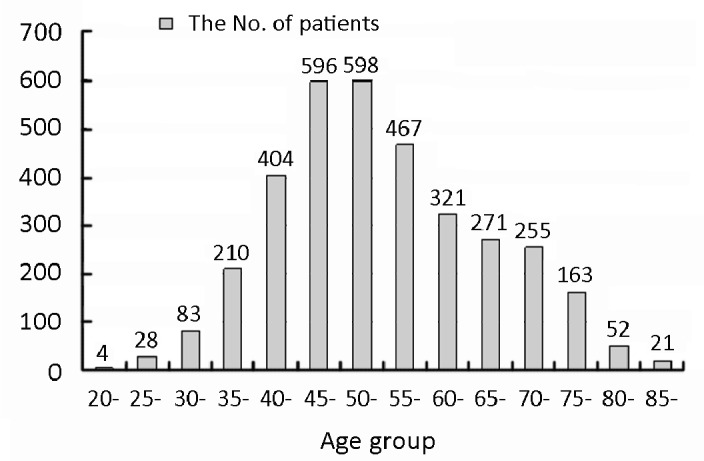

Among all 3473 patients, 3460 were females and 13 were males, with an average age of 54.4±12.1 years (range 20-92 years). The demographic characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 1. The age distribution of the patients in this study is shown in Figure 1.

Table 1. The general information of breast cancer patients in Beijing, 2008.

| Information | Number of patients | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 13 | 0.37 |

| Female | 3460 | 99.63 |

| Marital status | ||

| Unmarried | 51 | 1.47 |

| Married | 3353 | 96.54 |

| Divorced or widowed | 51 | 1.47 |

| Unknown | 18 | 0.52 |

| Menstrual status* | ||

| Premenopausal | 1991 | 57.54 |

| Postmenopausal | 1442 | 41.68 |

| Unknown | 27 | 0.78 |

| Diseases history | ||

| History of benign breast disease | 254 | 7.31 |

| Personal cancer history | 133 | 3.83 |

| Family history of breast cancer | 495 | 14.25 |

| Family history of cancer | 166 | 4.78 |

| Total | 3473 |

* Excluded 13 cases of male breast cancer

Figure 1.

The age distribution of breast cancer patients in Beijing, 2008.

The clinical tumor size was evaluated based primarily on ultrasonic or mammography record and secondarily on the document physical examination, 46.96% of the patients had tumors ≤2 cm. The pathological tumor size was defined according to the pathology report, and tumors ≤1 cm and 1-2 cm were 12.64% and 31.62%, respectively. 23.90% of the patients had no pathological document for tumor size. 36.14% of the patients had pathologically confirmed lymph node metastasis. 80.77% of the patients were invasive ductal carcinoma (Table 2).

Table 2. The clinical and pathological characters of breast cancer in Beijing, 2008 (n=3473).

| Number of cases | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical character | ||

| Tumor size (cm) | ||

| ≤2 | 1631 | 46.96 |

| 2-5 | 1491 | 42.93 |

| >5 | 128 | 3.69 |

| T4 | 126 | 3.63 |

| Not accessed | 97 | 2.79 |

| Pathological review | ||

| Tumor size (cm) | ||

| ≤1 | 439 | 12.64 |

| 1-2 | 1098 | 31.62 |

| 2-5 | 994 | 28.62 |

| >5 | 112 | 3.22 |

| Not assessed | 830 | 23.90 |

| Lymph node metastasis | ||

| No | 1953 | 56.23 |

| Yes | 1255 | 36.14 |

| Not assessed | 265 | 7.63 |

| Histological type | ||

| Carcinoma in situ | 160 | 4.61 |

| Invasive ductal carcinoma | 2805 | 80.77 |

| Invasive lobular carcinoma | 165 | 4.75 |

| Mucinous carcinoma | 108 | 3.11 |

| Other histological types | 214 | 6.16 |

| Without pathological diagnosis | 21 | 0.60 |

| ER/PR | ||

| + | 2511 | 72.30 |

| − | 673 | 19.38 |

| ± | 45 | 1.30 |

| No test | 244 | 7.03 |

| Her-2 | ||

| + | 476 | 13.71 |

| − | 2356 | 67.84 |

| Uncertain | 332 | 9.56 |

| No test | 309 | 8.90 |

| Total | 3473 |

Of all the cases, 3229 had document of estrogen receptor (ER) and/or progesterone receptor (PR), 72.30% of all the cases were ER and/or PR positive, 19.38% were ER and PR negative and 1.30% were uncertain, respectively. 3164 cases had document of Her-2 status, 476 (13.71%) were positive and 332 (9.56%) had uncertain status.

Detection and Diagnosis

Among 3473 patients, 2851 (82.09%) were symptomatic with the median time interval of one month from the initial self-awareness of the symptoms to visiting doctors. 17.33% of the cases were detected during regular physical examinations, and 30.07% of them were detected by image examination. The details of detection were listed in Table 3.

Table 3. The detection and diagnosis of the breast cancer in Beijing, 2008.

| Number of cases | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Detection | ||

| Breast self-examination | 2851 | 82.09 |

| Nipple inspection | 19 | 0.67 |

| Nipple discharge | 93 | 3.26 |

| Palpable neoplasm | 2598 | 91.13 |

| Other symptoms | 141 | 4.95 |

| Physical examination | 602 | 17.33 |

| Clinical breast examination | 421 | 69.93 |

| Image examination | 181 | 30.07 |

| Unknown | 20 | 0.58 |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Breast lesion | ||

| FNAB | 659/3465 | 19.02 |

| CNB | 1182/3465 | 34.11 |

| Frozen section/general pathology | 1624/3465 | 46.87 |

| Axillary staging | ||

| SLNB | 553 | 15.92 |

| BUS guided node needle biopsy | 212 | 6.10 |

| Immunohistochemistry examination | ||

| ER | ||

| No test | 243/3473 | 7.00 |

| Semi-quantitative in positive | 717/2269 | 31.60 |

| PR | ||

| No test | 245/3473 | 7.05 |

| Semi-quantitative in positive | 658/2179 | 30.20 |

All 99.77% of the patients were treated based on pathological diagnosis. Among them, 19.02% were diagnosed using fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB), 34.11% were diagnosed using core needle biopsy (CNB), and 46.87% were diagnosed through fresh frozen section biopsy. The rates of sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) and ultrasound guide FNAB ultras graphic abnormal axillary node were 15.92% and 6.10%, respectively (Table 3). There were 685 (19.72%) cases having the pathological information of axillary node before treatment.

In our study, 31.6% of the patients with positive ER status received semi-qualitative detection, and 30.2% of the patients with PR positive status received semi-qualitative detection.

Treatment

Among 3374 (97.15%) patients who received surgical therapy, 74.13% received mastectomy without breast reconstruction, 1.60% received mastectomy with reconstruction and 24.27% received breast conserving surgery. Among 2892 cases (83.27%) who underwent axillary lymph node dissection (ALND), 1666 cases (57.61%) were lymph node negative. Among all the cases with negative pathological node, only 245 cases (12.54%) saved ALND because of negative SLN (Table 4).

Table 4. The treatment in breast cancer patients in Beijing, 2008.

| Number of cases | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment | ||

| Final Surgery | 3374 | 97.15 |

| Breast | ||

| Mastectomy without reconstruction | 2501/3374 | 74.13 |

| Mastectomy with reconstruction | 54/3374 | 1.60 |

| BCS | 819/3374 | 24.27 |

| Axillary node | ||

| Axillary dissection | 2892/3473 | 83.27 |

| Negative node | 1666/2892 | 57.61 |

| No ALND for negative SLNB | 246/1953 | 12.54 |

| Radiotherapy | 943/3473 | 27.15 |

| Adjuvant systemic therapy | 3074/3473 | 88.51 |

| Chemotherapy | 2580/3473 | 74.29 |

| Endocrine therapy | 1316/3473 | |

| Anti-Her-2 therapy | 96/476 | 20.17 |

Among all the 2580 cases (74.29%) who received chemotherapy, 1316 (37.89%) had endocrine therapeutic records, and 943 cases (27.15%) had the radio therapeutic records. This may be underestimated because some patients may actually be treated in outpatients of more than two hospitals or use different IDs, whose clinical information was hardly captured completely by our survey.

Non-Standard Diagnosis and Treatment

Among 3473 cases, 0.6% of the breast cancer patients received clinical treatment without pathologic data. In the 160 patients with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) 105 (65.63%) received ALND and 59 (36.88%) received chemo- therapy. Of the 2580 patients received chemotherapy, 312 (12.10%) experienced chemotherapy less than 4 cycles.

Among the 819 cases received BCS, 212 (25.89%) had no pathological examination of margin status following breast conservative surgery (Table 5).

Table 5. Non-standard diagnosis and treatment in breast cancer patients in Beijing, 2008.

| Number of cases | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Immunohistochemistry examination | ||

| ER | ||

| No test | 243/3473 | 7.00 |

| PR | ||

| No test | 245/3473 | 7.05 |

| Her-2 | ||

| No test | 309/3473 | 8.90 |

| Pathological examination | ||

| No histopathological examination | 21/3473 | 0.60 |

| No histopathological grading | 1090/2805 | 38.86 |

| No tumor size | 830/3452 | 24.04 |

| Peritumoral vascular invasion (unknown) | 2320/3452 | 67.21 |

| Lymph nodes metastasis (unknown) | 265/3452 | 7.68 |

| Treatment | ||

| Surgery | ||

| BCS without mammography | 323/819 | 39.44 |

| ALND | 105/160 | 65.63 |

| BCS without radiotherapy | 212/819 | 25.89 |

| Radiotherapy | ||

| BCS without radiotherapy | 316/819 | 38.58 |

| After mastectomy if indicated without radiotherapy |

2662/435 | 60.23 |

| Chemotherapy | ||

| DCIS with chemotherapy | 59/160 | 36.88 |

| <4 cycles | 312/2580 | 12.10 |

| Endocrine therapy | ||

| HR-positive without endocrine therapy | 819/2511 | 52.45 |

| HR-negative with endocrine therapy | 62/673 | 9.21 |

The important information for treatment decision such as pathological tumor size, histological grade, the status of lymph nodes and the conditions of vascular thrombosis were missing in 24.04%, 38.86%, 7.68% and 67.21% of the patients, respectively.

The missing information of ER, PR and Her-2 status in the medical records of the breast cancer patients were 7%, 7.05% and 8.9%, respectively.

Of all the BCS patients, 316 (38.58%) and 262 (60.23%) patients had no records about radiotherapy after BCS and after mastectomy with radiotherapy indication, respectively. Among the above 578 patients without the information of radiotherapy, 350 cases were complemented through telephone interviews. It was confirmed that 93 cases (45.81%) received radiotherapy after BCS and 59 (40.14%) received radiotherapy after mastectomy. Of the patients with positive hormone-receptor (HR), 52.45% had no medical record about endocrine therapy. Among the 1692 cases without endocrine therapy, missing information of the endocrine therapy in 311 patients was complemented through telephone interviews and among them 249 (80.06%) received endocrine therapy and 62 (19.94%) did not. On the contrary, 9.21% of the HR-negative patients received endocrine therapy.

DISCUSSION

In our study, the infiltrating ductal cancer is the major type of breast cancer in Beijing with the proportion of 80.77% and infiltrating lobular cancer followed (4.75%). This is generally consistent with the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER), in which infiltrating ductal and lobular cancers accounted for 83.4% and 7.4%, respectively[4].

Among all breast cancer cases in this study, 72.30% were ER+ and/or PR+, and 19.38% were ER-/PR-, while in SEER data 79% of tumors were ER+ and/or PR+ and 21% were ER-/PR-[5]. The Her-2 status in USA was 19% aged ≤49 years, and 15% aged ≥50 years[6]. It is not evaluated in Beijing. The uncertain cases should be tested by FISH or CISH, however, they are not used widely in Beijing.

In terms of the tumor size, 46.96% were ≤2cm in diameter and 36.14% had lymph node metastasis, while in America according to the SEER data both proportions were significantly different, which were 75.9% and 26.3%, respectively between 1992 and 2003[7]. This reflects the notable delay of breast cancer diagnosis in Beijing that will inevitably affect the outcome negatively.

Since the 1990s, the national mammography screening was developed gradually in western countries. From New Mexico SEER files (n=5,067), the proportion of breast cancer cases detected by mammography screening was 76.8% from 1995 through 2004[8]. However, in Beijing only 17.33% of breast cancer cases were detected during routine physical examinations including palpation of doctors, ultrasonic imaging, mammography, and 30.07% of them were detected by image examination, which in part delay the early diagnosis. This result highlighted the importance of health education in general population and screening among high-risk women for the early detection of breast cancer.

Imaging guided needle biopsy is the first choice of tissue acquiring for histopathology while only 34.11% of cases were diagnosed by CNB.

In addition, we found that in the pathology reports, important information such as tumor size, histological grade, nodal status and vascular channel invasion were missing and the missing rates ranged from 7.68% to 67.21%. However, such information is important for treatment decision[9-15].

SLNB is the standard axillary staging procedure and negative SLNB is the indication for saving axillary dissection[16, 17]. According to the SEER data[18], from 1998 to 2004 the use of SLNB (±ALND) increased from 11% to 59% in USA. However, our study found only 15.92% (±ALND) received SLNB and among cases with pathological negative node, only 12.54% were diagnosed with SLNB and avoided axillary dissection.

In 1991, the NCI Consensus Conference stated that BCS was an appropriate primary therapy for the majority of females with early breast cancer. In a large population-based study using Medicare data from 2003 to 2004, the overall use of BCS in the elderly was 81.8% and varied minimally from 74% to 84% across the United States[19]. Japanese Breast Cancer Society reported 48.4% received BCS in 20417 cases in 2003[20]. However, only 24.27% of breast cancer cases underwent BCS in Beijing.

Among the proved Her-2 over-expression cases (476), only 98 patients received Herceptin therapy. It may be partly due to the reason that anti-her-2 treatment for primary breast cancer is not covered by health insurance in Beijing.

Over-treatment for DCIS was found frequently in breast cancer patients of Beijing. Although in NCCN, ALND is discouraged for patients with DCIS, our data showed that this therapy still prevailed, and some patients with DCIS received chemotherapy.

On the other hand, under-treatment was notable among patients undergoing surgery especially BCS. This was best represented by no pathological examination of margin following lumpectomy and no post-operative radiation therapy.

In the aspect of endocrine therapy, 52.45% of HR-positive patients had no record about treatment with endocrine drugs, though data missing and the presence of other conditions that may prevent the prescription (e.g. complications) could not be excluded. Nevertheless, some HR-negative patients received endocrine therapy, which obviously went against the treatment guidelines.

Through this mass survey without sampling error, we investigated the current status and found many non-standard practices in the diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer in Beijing, which remain to be addressed in the future.

Some limitations of the present study should be mentioned. Based on the review of medical records, our study inevitably suffered the impact of information bias. Furthermore, we did not collect data on potential causes for the non-standard practices and this deserves further study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, et al. GLOBOCAN 2008, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 10 [Internet]. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2010. Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr

- 2.National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). Breast Cancer. 2008. V2.2. Available from: http://www.nccn.org/profes sionals/physician_ gls/PDF/breast.pdf Accessed on June 10, 2008.

- 3.Goldhirsch A, Wood WC, Gelber RD, et al. Progress and promise: highlights of the international expert consensus on the primary therapy of early breast cancer 2007. Ann Oncol 2007; 18:1133-44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carter CL, Allen C, Henson DE. Relation of tumor size, lymph node status, and survival in 24,740 breast cancer cases. Cancer 1989; 63: 181-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dunnwald LK, Rossing MA, Li CI. Hormone receptor status, tumor characteristics, and prognosis: a prospective cohort of breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res 2007; 9:R6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cronin KA, Harlan LC, Dodd KW, et al. Population-based Estimate of the prevalence of HER-2 positive breast cancer tumors for early stage patients in the US [J] Cancer Investigation 2010; 28:963-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen SL, Hoehne FM, Giuliano AE. The Prognostic Significance of Micrometastases in breast cancer: a SEER population-based analysis. Ann Surg Oncol 2007; 14:3378-84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hill DA, Nibbe A, Royce ME, et al. Method of detection and breast cancer survival disparities in Hispanic women [J] Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2010; 19:2453-60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosen PP, Groshen S, Kinne DW, et al. Factors influencing prognosis in node-negative breast carcinoma: analysis of 767 T1N0M0/T2N0M0 patients with long-term follow-up. J Clin Oncol 1993; 11:2090-100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosen PP, Groshen S, Kinne DW. Prognosis in T2N0M0 stage I breast carcinoma: a 20-year follow-up study. J Clin Oncol 1991; 9:1650-61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fisher ER, Anderson S, Redmond C, et al. Pathologic findings from the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast Project protocol B-06. 10-year pathologic and clinical prognostic discriminants [J] Cancer 1993; 71: 2507-14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Truong PT, Berthelet E, Lee J, et al. The prognostic significance of the percentage of positive/dissected axillary lymph nodes in breast cancer recurrence and survival in patients with one to three positive axillary lymph nodes. Cancer 2005; 103:2006-14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith JA, 3rd, Gamez-Araujo JJ, Gallager HS, et al. Carcinoma of the breast: analysis of total lymph node involvement versus level of metastasis. Cancer 1977; 39:527-32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee AK, DeLellis RA, Silverman ML, et al. Prognostic significance of peritumoral lymphatic and blood vessel invasion in node-negative carcinoma of the breast. J Clin Oncol 1990; 8:1457-65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bettelheim R, Penman HG, Thornton-Jones H, et al. Prognostic significance of peritumoral vascular invasion in breast cancer. Br J Cancer 1984; 50:771-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Veronesi U, Galimberti V, Mariani L, et al. Sentinel node biopsy in breast cancer: early results in 953 patients with negative sentinel node biopsy and no axillary dissection. Eur J Cancer 2005; 41:231-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Naik AM, Fey J, Gemignani M, et al. The risk of axillary relapse after sentinel lymph node biopsy for breast cancer is comparable with that of axillary lymph node dissection: a follow-up study of 4008 procedures. Ann Surg 2004; 240:462-71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rescigno J, Zampell JC, Axelrod D. Patterns of axillary surgical care for breast cancer in the era of sentinel lymph node biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol 2009; 16:687-96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alderman AK, Bynum J, Sutherland J, et al. Surgical treatment of breast cancer among the elderly in the United States. Cancer 2011; 117:698-704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Japanese Breast Cancer Society Results of questionnaires concerning breast cancer surgery in Japan 1980-2003. Breast Cancer. 2005; 12:1–2 [Google Scholar]