Abstract

Objective

This study evaluated the social behavior of adolescents with ADHD in single and mixed gender treatment settings.

Method

We collected ratings of social behavior (i.e., prosocial peer interactions, assertiveness, self-management, compliance, physical aggression, relational aggression) during single and mixed gender games within the Summer Treatment Program-Adolescent (STP-A) for 10 girls (mean age 13.17, 80% Hispanic) and 11 boys (mean age 12.89, 54.55% Hispanic). Counselors completed ratings immediately following 10 recreational periods for each adolescent they supervised (5 single gender games, 5 mixed gender games). Gender (female versus male) x setting (single versus mixed gender) ANOVAs were conducted. If a significant interaction emerged, post hoc tests were also conducted.

Results

Several gender by setting interactions emerged, suggesting that girls benefit more from single gender formats than mixed gender formats. Girls showed more assertiveness, self-management, and compliance in single compared to mixed gender settings. A somewhat different pattern of results emerged for boys, which showed more appropriate social behavior (i.e., self-management, compliance) and less inappropriate social behavior (i.e., physical and relational aggression) in mixed gender settings compared to single gender settings.

Conclusions

In contrast to previous ADHD treatment studies, these findings suggest that gender may impact treatment response for adolescents. Therefore, it is important that future studies evaluate whether current treatments for ADHD are appropriate for girls with ADHD, and if gender-specific treatments are necessary to address the unique difficulties of adolescent girls with ADHD.

Keywords: ADHD, adolescents, gender, treatment

Peer relations are highly impaired in adolescents with ADHD (Bagwell, Molina, Pelham, & Hoza, 2001; Lee, Lahey, Owens, & Hinshaw, 2008). Compared to non-ADHD youth, adolescents with ADHD possess fewer friends, participate in fewer social engagements than their peers, and tend to associate with deviant peers (Bagwell et al., 2001). Emerging studies show that preadolescent girls with ADHD experience additional gender-specific social difficulties (Eme, 1992; Hinshaw & Blachman, 2005). For example, compared to preadolescent girls without ADHD, girls with the disorder engage in higher rates of relational aggression (Zalecki & Hinshaw, 2004), and these gender-specific difficulties continue into adolescence (Mikami, Hinshaw, Lee, & Mullin, 2008). Compared to their male counterparts, adolescent girls with ADHD also experience higher levels of depression, anxiety, self-esteem and body image problems (Mikami, Hinshaw, Patterson, & Lee, 2008), and each of these difficulties can exacerbate social impairment in females (Rose & Rudolph, 2006). Therefore, some suggest that gender-specific treatments are necessary to adequately address the social impairment of adolescent girls with ADHD (Hinshaw & Blachman, 2005).

Mixed gender settings are currently the standard of care for group-based behavioral peer interventions in adolescence (Pelham et al., 2010; Sibley et al., 2011). However, the mixed gender setting may suppress treatment effects for girls. Several studies have shown that girls engage in more delinquency in mixed versus single gender settings (Miller, Loeber, & Hipwell, 2009). In addition, much research has shown disadvantages for girls in mixed gender compared to single gender classrooms. Girls ask and answer fewer questions, and report feeling less comfortable and confident in mixed gender compared to single gender classrooms (Savicki, Kelley, & Ammon, 2002). Girls also interact and collaborate less freely with their peers, report feeling less able to learn new skills, and display more negative behavior in mixed compared to single gender classrooms (Savicki et al., 2002). These disadvantages are thought to be the result of differential teacher attention. Teachers provide more praise and corrective feedback to boys than girls in mixed gender settings, presumably because boys are generally louder and more disruptive than girls. There is also some evidence that teachers provide harsher discipline for girls than boys (Blakemore, Berenbaum, & Liben, 2009), and it appears that teacher biases exist for children with ADHD as well (Ohan & Visser, 2009).

Therefore, a single gender treatment setting may provide a more supportive environment for girls to receive corrective feedback on their behavior. Single gender treatment may also provide more relevant social interaction for girls than mixed gender treatment and more opportunities for therapists to reinforce these behaviors. Unique social skills are needed to navigate single and mixed gender settings in adolescence (Rose & Rudolph, 2006). Several studies have found that girls are less engaged in mixed gender group psychosocial treatments (depression: Chaplin et al., 2006; substance use: Hodgins, El-Guebaly, & Addington, 1997), which may be a result of differential patterns of interaction by gender. Boys tend to dominate group social interactions, while girls typically interact more collaboratively in dyads (Rose & Rudolph, 2006). Thus boys with ADHD may dominate social interactions within the mixed gender treatment setting, providing few opportunities for girls to practice and improve on gender-relevant communication skills. In addition, although standard behavioral peer interventions for ADHD are implemented in mixed gender athletic settings, most team sports are separated by gender in adolescence. Thus, involvement in single gender recreational activities could provide a more naturalistic peer environment for girls than a mixed gender setting, better for skill translation to interactions with typically developing adolescent girls.

This study evaluated the effect of single versus mixed gender settings on adolescent females’ response to an intensive behavioral peer intervention for ADHD. We collected counselor ratings of adolescent girls’ and boys’ social behavior during single and mixed gender therapeutic recreational activities within the Summer Treatment Program-Adolescent (STP-A; Sibley et al., 2011). Counselors reported on adolescents’ peer relations across six domains of social behavior (Caldarella & Merrell, 1997): positive peer interactions, compliance, assertiveness, self-management skills, and physical and relational aggression. We believed these domains would assess the range of social behaviors that have been shown to be impaired for adolescents with ADHD and have been impacted by the mixed versus single gender setting. Ratings of athletic skill were also collected to clarify that our findings were not confounded by athletic abilities. We hypothesized that compared to the mixed gender setting, the single gender setting would provide a more supportive environment for girls with ADHD, and that girls with ADHD would exhibit higher levels of prosocial behavior and lower levels of aggression in the single gender treatment setting compared to the mixed gender setting.

Method

Participants

Participants were 21 adolescents with ADHD (girls n=10, boys n= 11) who attended the 2011 STP-A (see Table 1 for demographic characteristics). The STP-A was offered as a clinical service at a university research center in urban South Florida. During the spring of 2011, advertisements for the STP-A were distributed to the research center’s client mailing list and to local school guidance staff. Parents and teachers completed an application of behavioral rating scales, demographic information, and treatment history. Teacher ratings were collected for all but one participant, whose teacher did not return the ratings. Parents also completed a semi-structured diagnostic interview consisting of DSM-III-R and DSM-IV descriptors for ADHD, ODD, and CD, with supplemental questions regarding situational and severity factors (Pelham, Gnagy, Greenslade, & Milich, 1992), and other comorbidities to determine whether additional assessment was needed (instrument available at http://ccf.fiu.edu). Adolescents completed brief IQ (WASI; Wechsler, 1999) and achievement tests (WIAT-II; Wechsler, 2002). Following DSM guidelines, diagnoses were made if a sufficient number of symptoms were endorsed (considering both parent and teacher reports). Through dual clinician review, participants were accepted to the STP-A if parent and teacher ratings indicated clinically significant impairment in ADHDrelated domains and a clinical profile appropriate for group treatment. All procedures were approved by university Institutional Review Board, and informed consent was obtained.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics

| Girls(n=10) | Boys(n=11) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (M, SD) | 13.17 (0.52) | 12.89 (0.47) |

| Race (% White) | 90.0 | 90.91 |

| Ethnicity (% Hispanic) | 80.0 | 54.55 |

| Single parent household (%) | 30.0 | 27.27 |

| ADHD Diagnosis (%) | ||

| ADHD Inattentive Type | 20.0 | 54.55 |

| ADHD Hyperactive Type | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| ADHD Combined Type | 70.0 | 45.45 |

| No Diagnosis | 10.0 | 0.00 |

| ODD (%) | 60.0 | 36.36 |

| CD (%) | 0.00 | 9.09 |

| Full Scale IQ (M, SD) | 100.70 (15.10) | 107.36 (5.37) |

| WIAT Reading (M, SD) | 105.70 (13.10) | 102.36 (12.76) |

| WIAT Mathematics (M, SD) | 108.10 (8.84) | 101.27 (19.31) |

| WIAT Spelling (M, SD) | 108.75 (12.88) | 100.30 (11.43) |

| ADHD medication during STP (%) | 60.0 | 36.36 |

| History of special education (%) | 60.00 | 72.73 |

| History of psychoactive medication (%) | 40.00 | 36.36 |

Note. No statistically significant or marginally significant group differences emerged on any demographic variables (p>.10)

Procedure

The STP-A is an 8-week intensive behavioral day treatment program for adolescents with ADHD (Sibley et al., 2011). Adolescents attended the program daily from 8:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. and participated in remedial skills training in: academics, organization, vocational training, and social relations. A full description of the program is described elsewhere (see Sibley et al., 2011). During the 2011 STP-A, two adolescent groups were formed. One group consisted of all girls (n=10) and the other consisted of all boys (n=11). Four staff members (3 females, 1 male) were assigned as primary counselors for each group. Despite grouping by gender, adolescents and counselors spent approximately half of the treatment in mixed-gender settings (e.g., lunch, end of day free time, special Friday activities).

Behavior Tracking System

Throughout the day, program staff provided adolescents with verbal feedback on positive behaviors (e.g., helping a peer, compliance with adult requests) and negative behaviors (e.g., teasing a peer, verbal abuse to staff members; Pelham et al., 2010). At the end of each day, adolescents received a success ratio that summarized their rate of negative behavior during the day. Staff members were trained to apply liberal use of positive reinforcement to their daily interactions with adolescents in conjunction with the behavioral feedback system. Serious misbehavior (e.g., intentional aggression, repeated noncompliance) resulted in an immediate restriction of program privileges until consistent good behavior was shown.

Therapeutic Recreational Activities

For two, hour-long periods each day, adolescents participated in therapeutic athletic activities for training in appropriate peer interactions. Adolescents received verbal feedback on social behavior from counselors who modeled appropriate game play, and led pre- and postactivity discussions designed to reinforce sports and social skills. As problems arose, adolescents participated in structured real time problem-solving discussions. Data were collected during single and mixed gender basketball and Ultimate Frisbee games that occurred during the fourth through eighth week of the STP-A. These games occurred for both girls and boys from 11:35 to 12:35 on Tuesday and Friday afternoons, and the format (i.e., single vs. mixed gender) alternated so that adolescents played one single gender and one mixed gender game each week. During the single gender periods, adolescents remained in their primary single-gender treatment groups, and their primary four counselors supervised and provided post-game ratings of their behavior. During mixed gender games, two mixed-gender groups were formed, with one mixed gender group including five girls and six boys, and the remaining girls and boys in another group. Adolescents were randomly assigned to one of the two mixed gender groups to eliminate potential biases in social preference or sport skill, and the two groups played separate games. The primary girl counselors supervised and rated one group and the primary boy group counselors supervised and rated the other.

Measures

Athletic performance

Sport skill was assessed in the last two weeks of the STP-A to detect covariation between gender and athleticism. Two adolescents (1 boy, 1 girl) were absent during athletic performance data collection, and their data was not collected. The authors assessed performance, with a second rater confirming accuracy of measurement. General athletic performance was measured by completion time in seconds for the 50-yard dash and the number of sit-ups completed in a minute. Basketball skills were assessed by the number of successful free throws (out of 10) and dribbling time through a pattern of cones, and Ultimate Frisbee skills were assessed by the number of completed passes (out of 10) and the number of accurate throws (out of 10). These measures have been shown to be reliable (Lopez-Williams et al., 2005). To support the validity of these assessments, counselors also completed a rating of adolescents’ general and specific athletic skills on the last day of the STP-A from 1 (not at all skilled) to 5 (very skilled), which were highly correlated to performance data reports (r=0.69-0.86). No gender differences emerged on any of the above indicators, and thus athletic skill was not included as a covariate.

Social skills performance

Counselors provided social skills ratings of each adolescent they supervised after each recreational period using a measure adapted from Caldarella and Merrell (1997). This measure included 20 items assessing prosocial peer interactions, assertiveness, self-management, and compliance, and we also added two items to assess physical and relational aggression on a 1 to 5 scale, in which 1=not at all, 3=somewhat, and 5=very much. Individual items and overall internal consistency coefficients are listed in Table 2. No significant differences emerged in ratings by primary and non-primary counselors. Ratings were collected twice a week from week 4 through 8, from 10 recreational periods (5 basketball, 5 Ultimate Frisbee). Three of the basketball periods were mixed gender games, while two were single gender games, and two of the Frisbee games were mixed gender, while three were single gender games.

Table 2.

Social behavior rating form

| Prosocial peer interactions (alpha=0.83) |

| How much did he/she compliment/praise/applaud his/her peers? |

| How much did he/she offer help or assistance to peers when needed? |

| How much did he/she invite peers to play/interact? |

| How much did he/she stand up for the rights of peers, defend a peer in trouble? |

| How much is he/she sought out by peers to join activities, everyone likes to be with? |

| How much was he/she sensitive to feelings of peers (empathy, sympathy)? |

| Assertiveness (alpha=0.74) |

| How much did he/she initiate conversations with others? |

| How much does he/she question unfair rules appropriately? |

| How much did he/she express feelings when wronged? |

| How much did he/she appear confident? |

| Self-management (alpha=0.78) |

| How much did he/she remain calm when problems arose? |

| How much did he/she compromise with others when appropriate? |

| How much did he/she accept criticism/feedback from others appropriately? |

| How much did he/she cooperate with others? |

| Compliance (alpha=0.79) |

| How much did he/she participate in the ongoing activity? |

| How much did he/she follow rules and accept imposed limits? |

| How much did he/she ignore distractions during the ongoing activity? |

| Physical aggression |

| How much did he/she physically hurt others? |

| Relational aggression |

| How much did he/she say or do non-physically harmful things (e.g., eye rolling, exclusion) to hurt others? |

Note. Positive peer interactions, assertiveness, self-management, and compliance items were adapted from Caldarella & Merrell (1997). All items were rated from (1) not at all to 5 (very much).

Treatment integrity and fidelity

Advanced graduate students conducted observations to measure and ensure treatment integrity and fidelity. Observations were conducted for approximately 80% of the recreation periods using a detailed list of recreational period procedures and requirements. Observers coded whether each treatment component (e.g., social reinforcement, group discussion) was accurately administered for each observed period. The percentage of appropriately administered treatment components was 99.1%, and the percentage agreement was 96.0%.

Data Analytic Plan

Analyses were conducted using SPSS 19. Chi-square and t-tests were conducted for demographic information. Social behavior scores were averaged across recreational period (i.e., basketball and Frisbee) and analyzed by 2 (gender: girl vs. boy) by 2 (setting: single gender vs. mixed gender) repeated measures ANOVAs. Assumptions of ANOVA were met for all social variables except physical and relational aggression were not normally distributed. Given the relatively infrequent rating above 1(not at all) on these items and the exploratory nature of our study, we did not correct for non-normality. Significant (i.e., p<.05) interactions were followed-up with post hoc planned comparisons. Effect sizes (i.e., partial eta-squared) were provided to assist the reader in interpreting the findings.

Results

Adolescent characteristics are described in Table 1. No demographic differences emerged.

Positive Peer Interactions

No significant interaction (F(1,705)=3.37, p=0.07, partial η2=0.01) or main effects of gender (F(1,705)=0.19, p=0.67, partial η2=0.00) or setting (F(1,705)=3.89, p=0.05, partial η2=0.01) emerged regarding positive peer interactions.

Assertiveness

A significant gender x setting interaction emerged for assertiveness (F(1,701)=10.91, p=0.00, partial η2=0.02). Follow-up tests revealed that girls were more assertive in single gender groups (p<.05) but format did not impact assertiveness ratings of boys. Setting impacted assertiveness (F(1,701)=9.09, p=0.00, partial η2=0.01), but gender did not (F(1,701)=3.85, p=0.05, partial η2=0.01).

Self-management

A significant gender x setting interaction emerged for self-management (F(1,699)=28.35, p=0.00, partial η2=0.04). Girls displayed more self-management in single versus mixed gender groups (p<.05), while boys displayed more self-management in mixed gender groups compared to single gender groups (p<.05). A main effect of gender (F(1, 699)=77.92, p=0.00, partial η2=0.10), but not setting (F(1,699)=0.22, p=0.64, partial η2=0.00), emerged.

Compliance

A significant interaction between gender and setting emerged (F(1,704)=26.12, p=0.00, partial η2=0.04). Girls displayed more compliance in single gender groups compared to mixed gender groups (p<.05), and boys were rated as displaying more compliance in mixed gender groups compared to single gender groups (p<.05). Gender (F(1,704)=57.93, p=0.00, partial η2=0.08) but not setting main effects (F(1,704)=0.20, p=0.66, partial η2=0.00) emerged.

Physical Aggression

A significant gender x setting interaction emerged (F(1,710)=4.61, p=0.03, partial η2=0.01). Boys were less aggressive in mixed gender compared to single gender groups (p<.05), but format did not impact girls’ aggression. Significant gender (F(1,709)=19.75, p=0.00, partial η2=0.03) and setting (F(1,710)=13.19, p=0.00, partial η2=0.02) effects emerged.

Relational Aggression

A significant gender x setting interaction emerged (F(1,710)=8.34, p=0.00, partial η2=0.01). Boys were less relationally aggressive in mixed gender groups compared to in single gender groups (p<.05), but format did not impact girls. Main effects of gender (F(1,710)=12.20, p=0.00, partial η2=0.02) and setting (F(1,710)=7.02, p=0.01, partial η2=0.01) emerged.

Discussion

This study investigated whether single versus mixed gender setting enhanced treatment response for female adolescents with ADHD. Several gender x setting effects emerged, showing more social benefit to girls in single versus mixed gender settings. Girls were rated as displaying more assertiveness, self-management, and compliance in single compared to mixed gender settings. Positive peer interactions and physical and relational aggression were unrelated to setting. For boys, mixed gender games were related to better self-management and compliance, and lower levels of physical and relational aggression. These findings are discussed in turn.

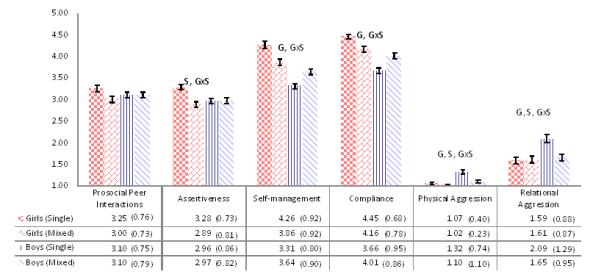

For girls (see Figure 1), the single gender setting elicited higher levels of assertiveness, self-management, and compliance. This is consistent with studies demonstrating that girls are more assertive in single gender classrooms (Blakemore et al., 2009) and exhibit higher rates of delinquent behaviors in the presence of boys (Miller et al., 2009). The positive behaviors elicited in single gender settings are highly relevant to the treatment of ADHD in females. For one, poor assertiveness in adolescent females is associated with negative outcomes (i.e., depression, risk behaviors; Keenan & Hipwell, 2005), many of which occur at higher rates in females with ADHD (Mikami et al., 2008). Furthermore, individuals with ADHD possess poor emotion regulation (Seymour et al., 2012), perhaps especially in females (Hinshaw & Blachman, 2005). Thus, self-management also may be a particularly important skill for girls with ADHD. We believe that single gender settings offer females with ADHD increased natural opportunities to practice these important skills.

Figure 1. Social skills by gender and setting.

Note. Higher scores reflect higher ratings on each domain. Responses on the counselor rating form ranged from (1) not at all to (3) somewhat to (5) very much. GxS=statistically significant interaction (p<.05). G=statistically significant main effect of gender (p<.05). S=statistically significant main effect of setting (p<.05).

If single gender treatment promotes critical prosocial behaviors in girls with ADHD, then counselors are afforded more opportunities to reinforce these behaviors. Girls may master social skills with greater ease in single gender settings due to antecedent variables that occasion skill use and increased opportunity for reinforcement from staff. As adequate rates of prosocial behavior are maintained, it may prove useful to transfer treatment to more challenging mixed gender settings for further skill development.

For girls, physical and relational aggression, as well as prosocial peer interactions, were not associated with setting. Very low levels of aggression were displayed by girls during the STP-A, which likely contributed to this null finding (see Figure 1). While we expected to find an effect for positive peer interactions, the sports periods may not provide an appropriate forum to display the type of behaviors measured by the rating form (see Table 2). For example, “how much was he/she sensitive to feelings of peers (empathy, sympathy)?” may not be an appropriate index of positive peer interaction when applied to a sports game.

A secondary finding was that boys (see Figure 1) displayed better self-management and compliance, and lower levels of physical and relational aggression in mixed gender versus single gender settings. This finding is consistent with previous studies showing increased benefit for boys in mixed gender versus single gender educational settings (e.g., Blakemore et al., 2009). Overall, girls were less physically aggressive than boys, which fits with studies showing that girls with and without ADHD are less overtly aggressive compared to boys (Gaub & Carlson, 1997; Rose & Rudolph, 2006). Girls were also more compliant and possessed better self-management than boys (see Figure 1). Therefore, it is possible that receiving treatment in the presence of more prosocial peers (regardless of gender) elicited prosocial behaviors in boys, and that our results could be influenced by a tendency for adolescents to conform to group behavior norms. However, children with ADHD have difficulties understanding social norms, and consistently display disruptive behavior in the presence of non-ADHD children (Hinshaw & Blachman, 2005), which suggests that adolescents with ADHD may have difficulties attending and adapting to group behavior norms. Furthermore, our findings regarding assertiveness, a social behavior consistently shown to be impacted by the mixed versus single gender setting for girls, did not suggest that girls’ behavior was clearly explained by conforming to group norms.

In addition, during early adolescence, many adolescents initiate opposite-sex romantic relationships. Consequently, they may display reticence to interact and be physically close or aggressive with the opposite sex (Rose & Rudolph, 2006), which may have led to better behavior for the boys in mixed gender settings. Some may believe that enhanced mixed gender treatment response for boys necessitates treatment delivery in mixed gender settings. However, research argues that when girls display gender atypical behavior, such as noncompliance, the social ramifications are worse than for boys, for whom disruptive behavior is more gender-typical (Eme, 1992). Therefore, the single gender setting could offer a more critical impact for girls than for boys, although no such studies exist. The boy to girl ratio in group treatment for ADHD is often at least 4:1 (Gaub & Carlson, 1997). Thus, girls may have limited opportunities to receive treatment in single gender environments. We believe clinicians should create opportunities for girls to receive some treatment components in single gender environments, even within mixed gender programs. Future studies are needed to determine whether the single gender setting is inappropriate, and perhaps unethical, for adolescent boys with ADHD.

Our findings suggest that adolescent girls with ADHD benefit more from single versus mixed treatment settings, but these findings must be interpreted cautiously. Despite statistically significant differences, effect sizes were modest, and we do not yet know if these benefits extend into other behavioral treatment settings or to interactions with girls without ADHD. Additionally, the findings reported herein are based upon counselor reports. Other assessments (e.g., behavioral frequency counts, self-ratings) may suggest a different pattern of results. Girls in our sample were more frequently diagnosed with ADHD-C and comorbid ODD compared to boys. Some research suggests that clinic-referred girls with ADHD have more severe behavior compared to boys (Eme, 1992), thus it is not clear whether our findings would generalize to understanding ADHD in community-based samples, in which girls typically manifest less severe behavior compared to boys with ADHD. Our sample was also predominantly white and Hispanic. Thus is it not clear how these findings would generalize to adolescents of other races and ethnicities. In fact, the majority of studies that have assessed gender differences among children with ADHD have not found many meaningful gender differences, including the MTA, the largest study of ADHD treatment to date (Owens et al., 2003). However, the MTA focused on children with ADHD, and there may be age-specific variables, particularly in the social context, which emerge by gender in adolescence. Furthermore, our relatively small sample size, although typical of research on girls with ADHD (Gaub & Carlson, 1997), reduces power to detect significant gender differences, and we were not able to explore other potential areas of interest such as the impact of counselor gender on ratings of adolescent social behavior. However, we had several ratings of behavior for each adolescent in each setting, and thus had comparatively more power to detect differences by setting, which was our primary concern.

Overall, both single gender and mixed gender settings evoked a high level of prosocial behavior for both adolescent boys and girls with ADHD, which likely occurred because adolescents responded well to the behavioral treatment in both settings (Sibley et al., 2011). However, our work suggests that there may be additional benefits to treating girls with ADHD in single gender settings. Altogether these results suggest gender may be an important factor of interest in ADHD treatment outcome for adolescents with ADHD. Future work must test whether this finding is robust to developmental stage by investigating whether the same is true for children with ADHD (e.g., Owens et al., 2003). It is our hope that similar investigations will further clarify whether single gender settings hold an important role in the treatment of adolescent girls with ADHD.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant AA11873 from the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Research was also supported in part by AA00202, AA08746, AA12342, AA0626, and grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA12414, DA05605, F31 DA017546), the National Institute on Mental Health (MH12010, MH4815, MH47390, MH45576, MH50467, MH53554, MH069614), the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (ES0515-08), and Institute of Education Sciences (IESLO3000665A, IESR324B060045).

References

- Bagwell CL, Molina BSG, Pelham WE, Hoza B. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and problems in peer relations: predictions from childhood to adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40(11):1285–1292. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200111000-00008. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200111000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore JEO, Berenbaum SA, Liben LS. Gender development. Taylor & Francis; New York: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Caldarella P, Merrell KW. Common dimensions of social skills of children and adolescents: a taxonomy of positive behaviors. School Psychology Review. 1997;26(2):264–278. [Google Scholar]

- Chaplin TM, Gillham JE, Reivich K, Elkon AGL, Samuels B, Freres DR, et al. Depression prevention for early adolescent girls. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2006;26(1):110–126. doi: 10.1177/0272431605282655. doi: 10.1177/0272431605282655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eme RF. Selective females affliction in the developmental disorders of childhood: a literature review. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 1992;21(4):354–364. [Google Scholar]

- Gaub M, Carlson CL. Gender differences in ADHD: a meta-analysis and critical review. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36(8):1036–1045. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199708000-00011. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2104_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw SP, Blachman DR. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. In: Bell-Dolan D, Foster S, Mash EJ, editors. Handbook of behavioral and emotional problems in girls. Kluwer Academic/Plenum; New York: 2005. pp. 117–147. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgins DC, El-Guebaly N, Addington J. Treatment of substance abusers: single or mixed gender programs? Addiction. 1997;92(7):805–812. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1997.tb02949.x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan K, Hipwell AE. Preadolescent clues to understanding depression in girls. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2005;8(2):89–105. doi: 10.1007/s10567-005-4750-3. doi: 10.1007/s10567-005-4750-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SS, Lahey BB, Owens EB, Hinshaw SP. Few preschool boys and girls with ADHD are well-adjusted during adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:373–383. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9184-6. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9184-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Williams A, Chacko A, Wymbs BT, Fabiano GA, Seymour KE, Gnagy EM, et al. Athletic performance and social behavior as predictors of peer acceptance in children diagnosed with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2005;13(3):173–180. doi: 10.1177/10634266050130030501. [Google Scholar]

- Mikami AY, Hinshaw SP, Lee SS, Mullin BC. Relationships between social information processing and relational aggression among adolescent girls with and without ADHD. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2008;37(7):761–771. doi: 10.1007/s10964-007-9237-8. doi: 10.1007/s10964-007-9237-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikami AY, Hinshaw SP, Patterson KA, Lee JC. Eating pathology among adolescent girls with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117(1):225–235. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.1.225. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.1.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller S, Loeber R, Hipwell A. Peer deviance, parenting, and disruptive behavior among young girls. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2009;37:139–152. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9265-1. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9265-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohan JL, Visser TAW. Why is there a gender gap in children presenting for Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder services? Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2009;38(5):650–660. doi: 10.1080/15374410903103627. doi: 10.1080/15374410903103627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens EB, Hinshaw SP, Kraemer HC, Arnold LE, Abikoff HB, Cantwell DP, et al. Which treatment for whome for ADHD? Moderators of treatment response in the MTA. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(3):540–552. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.3.540. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.3.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE, Gnagy EM, Greenslade KE, Milich R. Teacher ratings of DSM-III-R symptoms for the disruptive behavior disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1992;31(2):210–218. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199203000-00006. doi:10.1097/00004583-199203000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE, Sibley MH, Evans SW, Smith BH, Gnagy EM, Greiner AR. Summer treatment program for adolescents. 2010 doi: 10.1177/1087054711433424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose AJ, Rudolph KD. A review of sex differences in peer relationship processes: potential trade-offs for the emotional and behavioral development of girls and boys. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132(1):98–131. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.98. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savicki V, Kelley M, Ammon B. Effects of training on computer-mediated communication in single or mixed gender small task groups. Computers in Human Behavior. 2002;18(3):257–270. [Google Scholar]

- Seymour KE, Chronis-Tuscano A, Halldorsdottir T, Stupica B, Owens K, Sacks T. Emotion regulation mediates the relationship between ADHD and depressive symptoms in youth. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2012;40:595–606. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9593-4. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9593-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibley MH, Pelham WE, Evans SW, Gnagy EM, Greiner AR, Ross JM. An evaluation of the Summer Treatment Program for Adolescents with ADHD. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2011;18(4):530–544. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2010.09.002. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale – Third Edition. The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Wechler D. Wechsler Individual Achievement Test – Second Edition. The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Zalecki CA, Hinshaw SP. Overt and relational aggression in girls with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33(1):125–137. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3301_12. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3301_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]