Abstract

Nipah (NiV) and Hendra (HeV) viruses are the deadliest human pathogens within the Paramyxoviridae family, which include human and animal pathogens of global biomedical importance. NiV and HeV infections cause respiratory and encephalitic illness with high mortality rates in humans. Henipaviruses (HNV) are the only paramyxoviruses classified as biosafety level 4 (BSL4) pathogens due to their extreme pathogenicity, potential for bioterrorism, and lack of licensed vaccines and therapeutics. HNV use ephrin-B2 and ephrin-B3, highly conserved proteins, as viral entry receptors. This likely accounts for their unusually broad species tropism, and also provides opportunities to study how receptor usage, cellular tropism, and end-organ pathology relates to the pathobiology of HNV infections. The clinical and pathologic manifestations of Nipah and Hendra virus infections are reviewed in the chapters by Wong et. al. and Geisbert et.al. in this issue. Here, we will review the biology of the henipavirus receptors, and how receptor usage relates to henipavirus cell tropism in vitro and in vivo.

2. The Receptors

2.1 The Molecular Biology of ephrin-B2

Ephrin-B2 (also known as EPLG5, HTKL, Htk-L and LERK5) and ephrin-B3 are the cellular receptors for henipaviruses (Bonaparte et al. 2005; Negrete et al. 2005; Negrete et al. 2006). They belong to the ephrin family of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) comprising six GPI-anchored ephrin-As and three transmembrane ephrin-Bs (Eph Nomenclature Committee 1997). Ephrin-B2 and -B3 are type I transmembrane proteins of ~330 amino acids encoded on human chromosome 13 and 17, respectively. (Bennett et al. 1995; Bergemann et al. 1995). Ephrin family members are highly conserved: human and murine ephrin-B2 differs by only 3% at the amino acid level and many mammalian ephrin-B2 homlogs have been shown to bind henipavirus-G with similar affinities (Bossart et al. 2008).

By convention, ephrins (A and B) are designated as ligands for EphA and/or EphB receptors, which are also RTKs. Thus, cognate ephrin-eph interactions result in bidirectional signaling cascades: ephrins induce “forward” signaling through the eph receptors on the opposing cell, while Eph receptors initiate “reverse” signaling through the ephrin ligands (Cowan & Henkemeyer 2001; Zhao et al. 2006). Ephrin-Eph interactions are promiscuous, although the promiscuity, with a few exceptions, is limited to members within the same class (A or B). Structural evidence indicates that ephrin-B2 binds to its cognate receptors EphB4 and EphB2 via critical residues in a flexible “G-H loop” (amino acids 120–125) that fits into a shallow cleft on the opposing ephB receptors (Chrencik et al. 2006; Füller et al. 2003; Kobayashi et al. 2007). The functional signaling cascade seemingly arises from oligomeric interactions between clusters of ephrinB-ephB molecules at the point of cell-cell contact (reviewed in Wilkinson 2003).

Due to its function in mediating cell adhesion/repulsion, ephrin-B2 plays critical roles in chemotaxis and cell migration (Meyer et al. 2005), as evidenced by the fact that ephrin-B2 homozygous knock-out mice are embryonic lethals with defects such as primitive and uniformally sized vasculature, underdeveloped heart, and poor organization of the intersomitic vessels (Adams et al. 1999; Gerety & Anderson 2002). During neurogenesis, ephrin-B2 guides the migration of neuron precursors, contributing to the extremely precise organization pattern of brain cells (Zimmer et al. 2003); during vasculogenesis, the repulsion between EphB4-expressing vein precursors and ephrin-B2-expressing arterial precursors results in the formation of defined junctions between veins and arteries (Wang et al. 1998). Additionally, the function of ephrin-B2 has been extended to immune activation and bone formation in the adult body. EphB4-ephrin-B2- interaction has been shown to mediate the attachment of monocytes (EphB4 positive) to the endothelium (ephrin-B2 positive) during extravasation. Quite interestingly, while cytoplasmic tail deletion of ephrin-B2 does not affect monocyte attachment per se, it abolishes extravasation, suggesting that the “reverse” signaling through ephrin-B2 is required for this process (Pfaff et al. 2008). Similarly, during bone formation, “reverse” signaling downstream of ephrin-B2 in osteoclasts upon contact with EphB4-expressing osteoblasts regulates the proliferation of osteoclasts (Edwards & Mundy 2008; Zhao et al. 2006). A role for ephrin-B2 in lymph node remodeling has also been suggested (Mäkinen et al. 2005).

Similar to ephrin-B2, the alternative receptor for NiV, ephrin-B3, is also involved in axon guidance during neurogenesis. For examples, it acts as a midline repellent for axons of the corticospinal tract (Benson et al. 2005; Bergemann et al. 1998; Kullander et al. 2001).

2.2 Surface expression and regulation

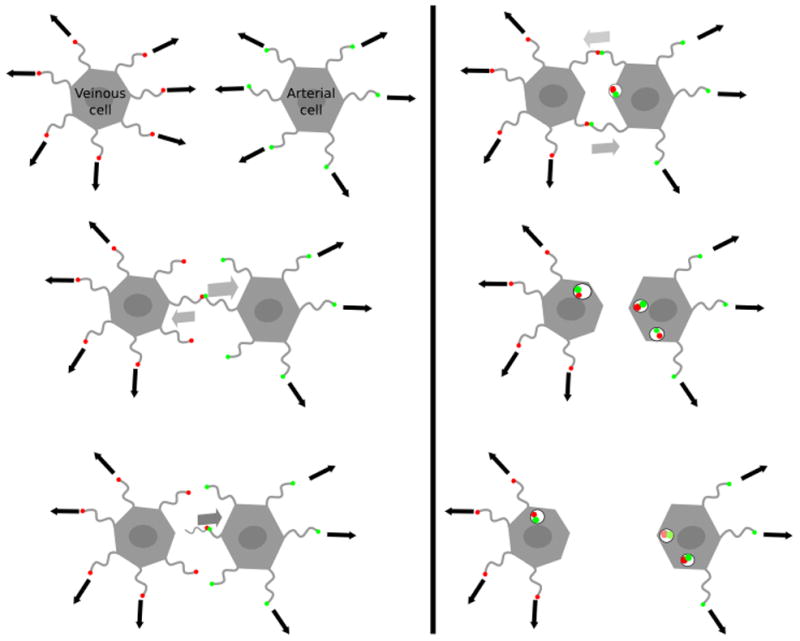

In some cases, ephrin-B2 protein is hardly detectable at the cell surface although its mRNA is present in these cells (Yoneda et al. 2006). One potential explanation could be that intramembrane proteases remove ephrins from the cell surface. For example, in cells that express rhomboid protease RHBDL2, ephrin-B3 is not detectable on the cell surface due to the efficient cleavage by this protease (Pascall & Brown 2004). In the case of ephrinB2, its extracellular domain can be cleaved by the Kuzbanian metalloproteinase upon interaction with EphB4 (Holmberg & Frisén 2002). It has also been demonstrated that the reverse signaling is dependant on the presence of Presenillin-1, an aspartyl protease from the γ-secretase complex. Presenillin-1 cleaves ephrin-B2 cytoplasmic tail into a C-terminal fragment (CTF) (Georgakopoulos et al. 2006), which regulates c-Src at two levels : first, CTF translocates to the nucleus where it activates c-Src transcription; second, CTF binds c-Src and therefore releases it from its inhibitor Csk. The c-Src-CTF complex then phosphorylates the cytoplasmic tail of uncleaved ephrin-B2 on tyrosine residues 304, 330 and 331(Georgakopoulos et al. 2011; Su et al. 2004). The phosphorylated ephrin-B2, in turn, activates a kinase cascade that induces membrane ruffling and membrane exchange, leading to cell-cell repulsion (Figure 1) (Holmberg & Frisén 2002; Wilkinson 2003). This kinase cascade may also intersect with the signals involved in cytoskeleton rearrangement and membrane extensions involved in macropinocytosis, a process that is thought to be involved in Nipah virus uptake upon viral attachment protein interaction with ephrin-B2.

Figure 1. Schematic illustration of EphB4/phrin-B2-mediated cell-cell repulsion.

Green dots represent ephrinB2. Red dots represent ephB4. Arrows indicate the direction of the filopodia extensions. Migrating cells move along the filopods they project. When ephrin-B2 on the surface of an arterial cell interacts with EphB4 on the surface of a venous cell, bi-directional signaling induces membrane ruffling and internalization of the EphB4-ephrin-B2 complex. Continued filopodia growth in opposite directions leads to the repulsion of these two cells. However, context dependent signaling can also lead to cell attraction and forward cell propulsion.

2.3 Distribution

Ephrin-B2

Consistent with its role in vasculogenesis, ephrin-B2 is expressed in endothelial and smooth muscle cells in arterial vessels and at angiogenesis sites (Gale et al. 2001). The brain is a main site of ephrin-B2 expression, especially during the fetal stage. Within the brain, the cortex (especially prefrontal) and neuroepithelial cells contain the highest levels of ephrin-B2, while its expression can also be detected in the olfactory bulb and the amygdala, albeit at lower levels. Outside of the brain, the placenta, lungs and the prostate contain abundant ephrin-B2 protein, and high levels of ephrin-B2 mRNA have also been detected in cardiomyocytes and bronchial epithelial cells (Liebl et al. 2003; Su et al. 2004) (BioGPS – probe ref.202668)

Ephrin-B3

With the possible exception of the prostate and heart, ephrin-B3 expression is mostly restricted to the central nervous system (CNS). It can be detected in the spinal cord and throughout the brain, with the highest levels found in the occipital lobe, the prefrontal cortex, and the amygdala. Lower levels can be detected in the pons, the globus pallidus, the subthalamic nucleus, the temporal lobe, the hypothalamus, the corpus callosum and the hippocampus (Benson et al. 2005; Liebl et al. 2003; Su et al. 2004) (BioGPS – probe ref.205031).

2.4 Receptor and host range

Due to its critical role during embryogenesis, ephrin-B2 (and B3) is evolutionarily conserved. It is found from fish and amphibians to mammals with relatively few changes. For example, the amino acid sequence similarity between human ephrin-B2 and ephrin-B2 from mice, pigs (as well as cats, horses and dogs), and fruit bats reaches 97%, 96% and 95%, respectively (Bossart et al. 2008). Even zebrafish ephrin-B2 (Danio rerio) is 65% similar to human ephrin-B2 at the amino acid level, and can even serve as entry receptors for NiV (unpublished observations). Thus, the conservation of ephrin-B2 may explain the unusually broad host range of henipaviruses compared to most other paramyxoviruses. Henipaviruses can infect several orders of the Class Mammalia under natural or experimental settings (see below). Remarkably, NiV innoculated into chicken embryos (Class Aves) also resulted in a histopathological picture that resembles that found in humans: severe leisions in the central nervous system with high viral antigenic load found in the vasculature and neurons (Tanimura N et al, 2006). The conservation of cross Class tissue tropism is unprecedented for a paramyxovirus, and it remains to be determined if henipavirus tropism extends outside the Superclass Tetrapoda to which Mammalia and Aves belong, to the Superclass Osteichthyes (bony fish), which includes the abovementioned Zebrafish.

The primary host for henipaviruses has been identified as fruit bats (family Megachiroptera) in the genera of Pteropus, Eidolon and Rousettus (Hayman et al. 2008; Hayman et al. 2011; Olson et al. 2002; Young et al. 1996). Although Microchiroptera species are generaly not infected (Hasebe et al. 2012), some have been detected seropositive for henipavirus (Li et al. 2008). Given that the bats comprise the second largest order in the class Mammalia (after rodents), with more than 1240 species constituting 20% of all known mammals, the finding of henipaviruses in both Megachiroptera and Microchiroptera suggests that henipaviruses may be more widely distributed than currently appreciated (Kunz et al. 2011).

During the HeV outbreaks in Australia, and the initial NiV outbreaks in Malaysia, horses and pigs, respectively, have been shown to act as intermediate amplifying hosts, transmitting the viruses from bats to humans (Chua 2010; Chua et al. 1999; Selvey et al. 1995). During the Meherpur outbreak (Bangladesh, 2001), cows have been suspected to be the amplifying host (Hsu et al. 2004). However, much epidemiological evidence suggests that, in Bangladesh, bats can transmit NiV directly to humans, and human-to-human transmission has also been documented (Homaira et al. 2010; Tan & Chua 2008).

Under laboratory conditions, the host range of henipaviruses can be extended to rodents (including golden hamsters (Wong et al. 2003), guinea pigs (Williamson et al. 2001; Williamson & Torres-Velez 2010), and ferrets (Bossart et al. 2009), and non-human primates (including African green monkeys (Old World monkey) (Geisbert et al. 2010; Rockx et al. 2010) and Saimiri/Squirell monkeys (New World monkey)(Marianneau et al. 2010). Notably, while hamsters and ferrets are readily infectable, and recapitulate many symptoms reflective of human infections (for details, see the review on animal models for henipaviruses in this issue), mice are resistant to NiV infection (Wong et al. 2003) despite the fact that murine ephrin-B2 shares 97% sequence similarity with human ephrin-B2. Other animals that are susceptible to henipavirus infection, at least under laboratory conditions, include cats, dogs (Hooper et al. 2001; Mills et al. 2009; Mungall et al. 2006) (class Mammalia), and chicken embryos (Tanimura et al. 2006) (class Aves) as discussed above. The curious exception of murine resistance to henipavirus infection likely occurs at a post-entry step, as the henipavirus attachment glycoprotein binds to murine ephrinB2 just as well as human ephrinB2 (Bossart et al. 2008).

2.5 Ephrins and henipavirus cellular tropism in vitro

The susceptibility of a given cell line to henipavirus infection in vitro largely depends on its ephrin-B2/B3 expression. For example, the hamster cell line CHO lacks any endogenous ephrinB expression, and expression of exogenous ephrin-B2 and -B3 (but not -B1) renders CHO cells highly permissive to NiV infection (Negrete et al. 2006). Most of the common cell lines used in the laboratory (including HEK293T, vero, HeLa-CCL2, but not the HeLa-USU subclone) can support henipavirus infection (see table 1). On the other hand, although known to be endothelial-tropic, NiV is not able to infect all the endothelial cell lines. Endothelial cells from the capillaries and the brain such as PBMECs (porcine microvascular endothelial cells) and HBMECs (human brain endothelial cells), which express high levels of ephrin-B2, are susceptible to NiV infection, whereas PAECs (porcine aorta endothelial cells) and MyEnd (murine myocard), which do not express detectable levels of the receptors, are resistant to infection (Erbar et al. 2008).

Table 1.

Cell line tropism of henipaviruses and receptor expression.

| Cell line | Species/Type | ephrinB2 | ephrinB3 | Infectability | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHO | Chinese Hamster Ovary | − | − | − | (Negrete et al. 2005) |

| CHO B2 | Stably expressing ephrin-B2 | + | − | + | (Negrete et al. 2005) |

| CHO B3 | Stably expressing ephrin-B3 | − | + | + | (Negrete et al. 2005) |

| HeLa-CCL2 | Human Uterus | + | + | (Bonaparte et al. 2005) | |

| HeLa-USU | Human Uterus | − | − | − | (Bonaparte et al. 2005) |

| Vero | Vervet kidney epithelial | + | + | + | (Bossart et al. 2005; Erbar et al. 2008) |

| MyEnd | Myocard Endothelial | − | − | − | (Erbar et al. 2008) |

| HBMEC | Human brain endothelial | + | − | + | (Erbar et al. 2008) |

| PBMEC | Porcine brain microvascular endothelial | + | + | + | (Erbar et al. 2008) |

| PAEC | Pig Aorta | − | − | − | (Erbar et al. 2008) |

| PK13 | Pig Fibroblast | − | − | − | (Negrete et al. 2005) |

| BHK | Hamster Kidney | + | + | (Yoneda et al. 2006) | |

| 293T | Human Kidney (endothelial) | + | + | (Yoneda et al. 2006) | |

| 4/4RM4 | Rat epithelial | + | ND | + | (Yoneda et al. 2006) |

| L2 | Rat lung epithelia | + | ND | + | (Yoneda et al. 2006) |

| 208f | Rat embryonic fibroblast | + | ND | − | (Yoneda et al. 2006) |

| P815 | Mouse mast cell | + | ND | − | (Yoneda et al. 2006) |

| PCI 13 | Human head and neck carcinoma | ND* | ND* | + | (Bossart et al. 2005) |

| U373-MG | Human Glioblastoma | ND* | ND* | + | (Bossart et al. 2005) |

These cells have been tested positive for “a receptor”. However, this receptor has not been identified in the abovementoned reference.

So far, most cell lines with detectable ephrinB2 expression have been shown to be permissive to NiV infection with the possible exception of P815 (mouse mast cells) and 208f (rat embryonic fibroblasts). It is unclear why these cell lines are unable to support NiV replication, but in the case of 208f, interestingly, the amount of ephrinB2 at the cells surface as detected by flow cytometry is low although the mRNA is present at high levels. It is possible that the receptor may be downregulated by intramembrane proteases similar to what has been shown for ephrin-B3/-B2 and Rhomboid proteases as discussed above. A list of cell lines with their ephrin-B2/B3 expression profiles and infectability phenotypes is shown in Table 1

3. Glycoprotein-receptor interaction

3.1 The attachment glycoprotein G

The henipavirus attachment glycoprotein is a type II transmembrane protein (602 and 604 amino acids for NiV-G and HeV-G, respectively). It shares structural similarities with the attachment glycoproteins of other paramyxoviruses (Bowden et al. 2008a; Xu et al. 2008). These include an N-terminal cytoplasmic tail, a single transmembrane domain, a stalk region, and a globular head that folds as a six-bladed β-propeller barrel with a central canyon on the membrane-distal face (Bowden et al. 2008a; Xu et al. 2008). Despite these structural similarities, henipavirus-G does not possess hemagglutination (H) or neurominidase (N) activities, features that are common to most other paramyxoviruses (reviewed in (Lee & Ataman 2011). In addition, the stalk region of henipavirus-G is about 40 amino acids longer that the HN stalk from paramyxoviruses that use glycan-based receptors (sialic acids) (respiroviruses, rubulaviruses, and avulaviruses), but is similar in length to the H stalk in morbilliviruses (the only other genus that uses protein-based receptors) (Marr et al, 2012). On the other hand, structural phylogeny analysis of the globular head domain indicates that henipavirus-G is more closely related to the HN attachment glycoproteins from glycan-using paramyxoviruses than to the H attachment glycoprotein from morbilliviruses (using measles H as the representative example) (Bowden et al. 2008a; Bowden et al. 2010b). HN is thought to be the ancestral protein—thus, the hybrid features of henipavirus- G suggest that henipavirus-G independently evolved to use protein-based receptors after MeV- H’s own switch from using glycan-based to protein-based receptors. The more recent evolutionary history of henipavirus-G may contribute to the relatively broad species tropism of henipaviruses, unlike measles virus, which has had more time to adapt to using only the cognate receptors (CD150/SLAM) from humans and certain non-human primates (Hashiguchi et al, 2011a).

There is biochemical evidence that Henipavirus-G oligomerizes as a dimer of a dimers (Bishop et al. 2008; Maar et al, 2012), consistent with the tetrameric assembly found for other paramyxoviral attachment proteins (Lamb et al. 2006; Yuan et al. 2008). Positional analysis of glycosylation sites and other structural modeling criteria suggest that henipavirus-G has a dimerization interface that is conserved amongst Paramyxoviridae (Bowden et al. 2008b; Bowden et al. 2010a) although the relative angle of dimer association and the area of the dimer interface differs between henipaviruses, morbilliviruses and other glycan-using paramyxoviruses (reviewed in Lee & Ataman 2011). Recent work on the structure of the NDV globular domain crystallized with part of its stalk region indicates that the stalk region adopts a 4-helix bundle that holds the tetrameric assembly together (Yuan et al. 2008; Yuan et al. 2011b). Strikingly, each pair of globular head domains was titled almost at right angles with respect to the other pair, exposing the four receptor-binding sites in four different directions. It is unclear whether henipavirus-G will also adopt this configuration—if it does, these putative structural features might place highly restrictive constraints on how the ephrinB2/B3 “G-H” loop can access the receptor binding cleft in the globular head of henipavirus-G.

3.2 Henipavirus-G-receptor interaction

Upon binding to its cellular receptor ephrin-B2 or –B3, conformational changes in NiV-G contribute to the “triggering” of the fusion protein F, leading to the fusion between viral and cellular membranes (for details, please see review by Aguilar and Iorio in this issue). The solvent exposed “G-H” loop of ephrin-B2/B3 is important for interacting with the endogenous EphB receptors, as well as the henipavirus-G proteins (Bowden et al. 2008a; Himanen et al. 2007; Xu et al. 2008). However, compared to EphB4 (or EphB2), both NiV-G and HeV-G have ~10-fold higher affinity for ephrin-B2 (Kd in the picomolar range) (Negrete et al. 2007). This is the highest affinity viral envelope-receptor interaction known to date, and likely reflects selective pressures under which henipaviruses have evolved to use ephrinB2/B3 as a receptor. For example, Eph/ephrin interactions, though highly promiscuous, are regulated in part by the strength of the signaling that results from clusters of Eph/ephrin interactions at the cell-cell interface. The high affinity of henipavirus-G for ephrin-B2/B3 may have evolved to compete effectively with the high avidity interactions that result from clusters of endogenous Eph/ephrin interactions.

Henipavirus-G-ephrin-B2 interaction mimics the endogenous EphB4-ephrin-B2 interaction in that the “G-H loop” of ephrin-B2 (amino acids 120–125) is important for binding in both cases; mutation of critical amino acids in this region results in altered binding and fusion phenotypes (Negrete et al. 2006; Pernet et al. 2009; Yuan et al. 2011a). However, compared to EphB4 (or EphB2), both NiV-G and HeV-G have ~10-fold higher affinity for ephrin-B2: soluble NiV-G and HeV-G bind ephrinB2 expressing cells with a Kd of 0.27nM and 0.57 nM, respectively. In contrast, NiV-G appears to bind ephrinB3 with a higher affinity than HeV-G (Kd=0.78nM vs 24.3nM, respectively). This difference has been localized to a valine (NiV) to serine (HeV) change in residue 507 (Negrete et al. 2007). Curiously, an updated HeV-G sequence has a theronine at residue 507, and this serine to theronine change largely, though not completely, restores the ephrinB3 binding affinity to NiV-G levels.

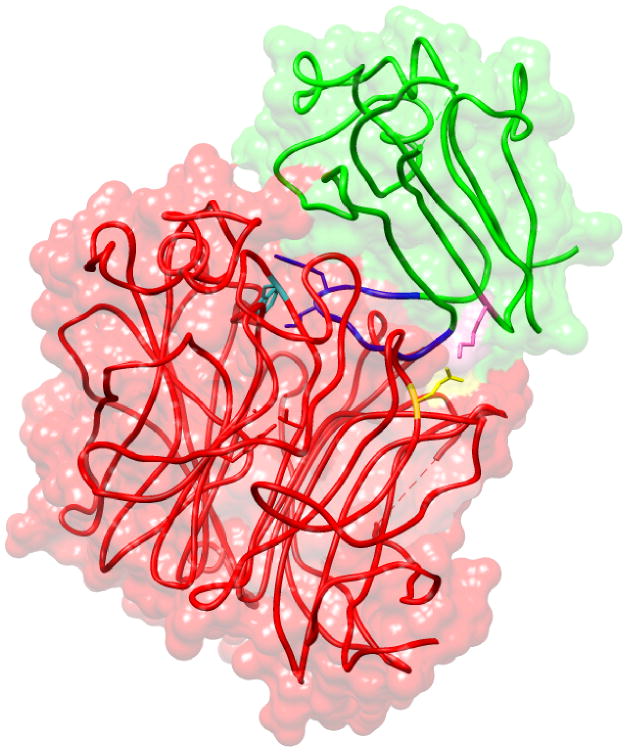

The residues critical for receptor binding on NiV-G was functionally mapped to E533, W504 and E505 (Guillaume et al. 2006; Negrete et al. 2007) and confirmed by crystallography (Bowden et al. 2008a, Xu et al, 2008). As show in Fig 2, NiV-G E533 makes contact (via a salt bridge) with residue K60 on ephrin-B2. This helps to orientate the “G-H loop” of ephrin-B2 in the hydrophobic canyon of NiV-G in a way that facilitates the interaction between the “G-H loop” and the amino acids lining up the surface of the canyon. E533 makes a similar charge-charge interaction with R57 on ephrin-B3. Since these interactions are important for stabilizing the binding of both ephrin-B2 and ephrin-B3, a single point mutation E533Q reduces NiV-G-mediated syncytia formation and entry by 90%. Interestingly, residue 533 on Measles virus H protein (MeV-H) is also critical for its binding to the CD150/SLAM receptor, although the charge-charge interaction is reversed with R533 on MeV-H interacting with E123 on SLAM (Hashiguchi et al. 2011b; Massé et al. 2004; Tatsuo et al. 2000). This raises intriguing questions regarding the evolution of two independent genera of protein receptor using paramyxoviruses (G and H) from the likely ancestral glycan-using paramyxovirus (HN) (Lee and Ataman, 2011).

Figure 2. Interaction between NiV-G and ephrin-B2.

Basic amino acid residue K60 (pink) of ephrin-B2 (green) forms a salt bridge with acidic amino acid E533 (yellow) of NiV-G (red), guiding the GH-Loop of ephrin-B2 (blue) into the hydrophobic canyon located at the top of NiV- G globular head. Amino acid W504 (cyan) of NiV-G, located in the hydrophobic canyon, is important for differential binding to ephrinB2 versus ephrinB3. Based on PDB ID:2VSM

3.3 The internalization of viral particles

The membrane fusion mediated by paramyxoviral glycoproteins is known to be pH independent and can presumably occur on the plasma membrane of the target cell. However, NiV has also been shown to exploit the cellular macropinocytosis pathway, potentially to its own advantage (Pernet et al. 2009).

Similar to the cognate receptor EphB4, NiV-G triggers the activation of ephrin-B2 by phosphorylation on specific tyrosine residues in the cytoplasmic tail. However, while residues Y304, Y330 and Y331 of ephrin-B2 are all involved in EphB4-triggered downstream events, only Y304 phosphorylation seems critical for “reverse signaling” during NiV-G binding (Pernet et al. 2009; Su et al. 2004). Subsequently, phospho-tyrosines 304 recruit the adaptor protein Grb4 (also known as Nck2) (Cowan & Henkemeyer 2001) which, in turn, recruits Ras and activates multiple downstream pathways involved in intracellular vesicle trafficking (Arf6), actin remodeling and membrane ruffling (Rab5/RNtre and PI3K/PKC/Rab34), and regulating the switch between macropinocytosis and filopodia formation (Rac1/Cdc42) (Bucci et al. 1995; Marston et al. 2003; Radhakrishna et al. 1999; Sun et al. 2003). A panoply of assays using inhibitors of macropinocytosis and actin depolymerization, suggest the Nipah virus-ephinB2 complex is internalized (Pernet et al. 2009) in a manner not unlike the bidirectional endocytosis seen for EphB4-ephrin-B2 complexes when they interact on opposing cells (reviewed in Pitulescu & Adams 2010)

Many viruses appear to use macropinocytosis to facilitate entry. Examples include vaccinia (Poxviridae) (Mercer & Helenius 2008), Dengue virus (Flaviviridae) (Suksanpaisan et al. 2009; Zamudio-Meza et al. 2009), and Ebola virus (Filioviridae) (Saeed et al 2010). Measles virus, another paramyxovirus that uses protein-based receptors for entry, can cross-link CD46 (a cognate receptor for the vaccine strain) and induce pseudopodia engulfment in a process similar to macropinocytosis (Crimeen-Irwin et al. 2003). Rac1/Cdc42-mediated internalization triggered by ephrin-B2 signaling is a well-established pathway in endothelial cells (Vandenbroucke et al. 2008). Co-opting this pathway in its natural target cell may have advantages for the virus: (1) rapid internalization potentially helps the virus to evade host immune recognition, and (2) downregulation of ephrin-B2 from the cell surface (Pernet et al. 2009) may also prevent super-infection and facilitate the release of progeny virions.

4. Receptor usage and henipavirus pathogenesis

4.1 Pathology and symptoms

Henipavirus infection leads to vasculitis, necrosis, thrombosis, as well as brain parenchyma lesion associated with the formation of giant multi-nucleated cells (for details, see the review on “Clinical and pathological manifestations of human henipavirus infection” in this issue). These cytopathic effects are largely due to the syncytia-inducing ability of NiV and HeV glycoproteins, and the sites of lesion match ephrin-B2/B3 expression profiles.

The clinical presentations following henipavirus infection include neurological symptoms (eg. headaches, drowsiness, disorientation, myoclonus, motor and sensory loss), respiratory disorders (observed in HeV-infected horses, NiV-infected pigs, and 25–40% of NiV-infected humans), unstable blood pressure, and, in one case, vision loss (Chua et al. 1999; Lim et al. 1999; Lim et al. 2003; Wong et al. 2002). 40–92% of NiV-infected humans succumb to acute encephalitis with an average time of 10 days from fever onset to death, while 3–7% of infected patients exhibit a late onset or relapsed encephalitis months to years after the initial infection (Chua et al. 1999; Luby et al. 2006).

4.2 Ephrin-B2/B3 and NiV pathogenesis

The pathology and symptoms associated with NiV infection can, in some cases, be explained by the expression pattern of ephrin-B2/B3 in vivo and the resultant cellular tropism of the virus (see table 2). The more generalized symptomology may be a result of the inflammatory response directed against the replicating virus once it has established a primary infection.

Table 2.

Examples of infected sites and the related pathobiology

| Site | Pathology | Symptoms | Receptor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lungs | Microvascular destruction | Cough and other respiratory disorder | ephrinB2 |

| Retinal artery | Artery occlusion | Vision loss | ephrinB2 |

| CNS | BBB rupture | Motor and sensory loss, encephalitis | ephrinB2 |

| Syncytia in brain parenchyma | ephrinB2 / B3 | ||

| Liver | - | None | - |

A hallmark of henipavirus infection is the cellular pathology that results from the infection of microvascular endothelial cells (Hooper et al. 1997a; Hooper et al. 1997b; Wong et al, 2002). Syncytia formation induced by infection results in endothelial cell dysfunction and apoptosis; in the end-organ microvasculature, this can lead to vascular inflammation and thrombosis. At autopsy, widespread vasculitis is seen in the lung (62%), heart (31%), kidney (24%), and the CNS (80%) (Wong et al. 2002), concordant with the high expression levels of ephrin-B2 in these tissues (Hafner et al. 2006). Focal perivascular necrosis was observed in most of the highly vascular organs, with the spleen being the most striking example. Furthermore, viral antigen staining was particularly evident in the periarteriolar sheaths in the white pulp (Wong et al. 2002), which is the only region in the spleen where ephrin-B2 expression can be detected (Gale et al. 2001).

In the CNS, where severe damage to vessels was seen in 80% of the patients, vasculitis presumably results in the disruption of the blood-brain barrier, allowing the virus access to the CNS where it can infect ephrin-B2 and B3-positive cells in the brain parenchyma (Wong et al. 2002). However, it is also possible that infected brain microvascular endothelial cells produce virus that bud out from the basolateral surface and therefore gain access to the CNS without a breach in the BBB. There is evidence that the cytoplasmic domain of the Nipah F and G proteins contain basolateral targeting signals, at least when examined in polarized epithelial cells (Weise et al. 2010). Of course, both these pathological models are not mutually exclusive, and in all likelihood, occur together and contribute to the devastating sequalae of the disease.

Consistent with the diffuse expression pattern of ephrin-B2 in the brain, MRI scans of acutely infected patients reveal multiple hyperintense lesions in the cortex, pons, putamen, and the cerebral and cerebellar peduncles. These lesions may underlie some of the neurological symptoms seen in Nipah infected patients (see the chapter by Wong and Tan in this issue). Interestingly, ephrinB3, but not ephrinB2, is also expressed in the brainstem (Negrete et al. 2007). Neurological symptoms reflective of brainstem involvement such as coma, abnormal doll’s-eye reflex, abnormal pupils, and segmental myoclonus are bad prognostic factors, and brain stem neuronal dysfunction is thought to be the major cause of death in Nipah virus encephalitis (Goh et al. 2000). In the African green monkey model of Hendra virus infection, localized lesions of intense viral antigen staining can also be seen in the brainstem (Bossart et al. 2011). Thus, although ephrinB2 likely serves as the receptor that allows for establishment of a primary henipavirus infection, ephrinB3 mediated cellular pathology may also contribute significantly to the ultimate cause of death.

Henipavirus transmission from mother to fetus has been observed in the fruit bats, the natural reservoir for henipaviruses, consistent with the expression of ephrin-B2 in the placenta (Williamson et al. 2000). In addition, vertical transmission and fetal replication of Nipah virus has been documented in an experimentally infected cat (Mungall et al. 2007). There is some speculation that the seasonal uptick in henipavirus spill-over events is associated with breeding cycle of the Asian fruit bats, which give birth in the winter (Jan-Mar in Bangladesh, May-Oct in Australia)(McFarlane et al. 2011; Plowright et al. 2008; Wacharapluesadee et al. 2010).

5. Alternative tropism and trans-infection

Blood cells (including lymphocytes and monocytes) in general are not permissive to NiV infection (with the possible exception of dendritic cells, in which low levels of viral replication have been detected) (Mathieu et al. 2011). However, they can efficiently transport the virus from one infection site to another or even to a new host, as suggested by a recent study (Mathieu et al. 2011). This lymphocyte-mediated trans-infection is likely due to the binding of the virus to the cell surface via its glycoproteins without establishing a productive infection. Indeed, the virus can bind to the cell surface in a receptor-independent manner, since binding can occur in CHO cells which do not express detectable levels of ephrin-B2 or B3, and trans-infection can be abolished by C-type lectin inhibitors (Mathieu et al. 2011). These results are consistent with an earlier report by Bowden et al showing that NiV-G can act as a putative ligand for the endothelial cell lectin, LSECtin (Bowden et al. 2008b).

6. Perspectives

Ephrin-B2 and B3, the cellular receptors for henipavirus entry, are mainly expressed in neuronal and endothelial cells. Receptor expression largely determines the cellular tropism of henipaviruses, which is underscored by the high level of concordance between ephrin-B2/B3 distribution pattern in vivo and henipavirus-induced cellular pathology. Although much has been done to elucidate the receptor interactions and tropism of henipaviruses, the entry route of the virus into the human body still remains elusive. In Bangladesh, it has been documented that people can acquire NiV infection by drinking contaminated date palm sap (Luby et al. 2006; Rahman et al. 2012). Since the cells in the epithelium of the digestive tract do not express the henipavirus receptors, and the virus is sensitive to low pH exposure (Fogarty et al. 2008), how the virus manages to reach the susceptible cell types to establish a primary infection in this case is not clear. It is possible the virus may gain access to tissue macrophages and/or dendritic cells in the oropharyngeal submucosa through microscopic lesions commonly found in the mouth and throat. Macrophages in inflamed tissues such as the gingiva in periodontal disease, and the tonsils in general, express high levels of ephrinB2 (Yuan et al. 2004; Yuan et al. 2000) even if cultured monocyte-derived macrophages do not (Bossart et al. 2001). Binding to macrophages (or dendritic cells) may also allow the virus can be carried to permissive cells via “trans-infection” as discussed above).

An alternative explanation is that NiV is able to use another receptor for entry in the absence of ephrinB2 and B3, similar to MeV. It has been known for a while that epithelial cells, which lack CD150/SLAM and CD46, are permissive for MeV infection. This elusive epithelial cell receptor was recently identified as nectin-4 (Noyce et al, 2011; Mühlebach et al. 2011). Since nectin-4 is expressed in epithelial cells (especially tracheal cells), it may facilitate the initial infection through the respiratory tract in addition to the well-established route of host entry via transmigrating alveolar macrophages, although it has been proposed as the exit receptor used by MeV to cross the tracheal epithelium and emerge in the airways (Mühlebach et al. 2011). Given the structural similarity between NiV-G and MeV-H, it is possible that similar mechanisms might exist for NiV-G as well.

Although henipavirus infections have a high mortality rate, spill-over events into the human population remain rare. Preventive measures such as the use of universal precautions to protect against contaminated fluids from infected horses (Australia) or public education campaigns against drinking raw palm date juice appears to be the most cost-effective interim measures for preventing spread in the human population (Luby et al. 2009; Nahar et al. 2010). Many therapeutic strategies have been investigated (reviewed in Aguilar & Lee2011; Vigant & Lee 2011), and promising vaccine candidates are being advanced through the pipeline (see chapter by C. Broder in this issue). The high affinity for henipavirus-G for its ephrinB receptors makes it difficult to directly antagonize this molecular interaction via traditional small molecule therapeutics. However, passive immunotherapy with a monoclonal antibody that blocks henipavirus-G-receptor interactions appears promising, and even exhibits post-exposure efficacy when administered up to 72 hours post-infection in the African green monkey model (Bossart et al. 2011). Nonetheless, the considerable knowledge gained from the study of the henipavirus-G proteins and their receptors can potentially be harnessed for use in therapies that target the ephrinB2-EphB4 axis that is implicated in the tumorigenesis or tumor angiogenesis in certain cancers (reviewed in Pasquale 2008).

References

- Adams RH, Wilkinson GA, Weiss C, Diella F, Gale NW, et al. Roles of ephrinb ligands and ephb receptors in cardiovascular development: demarcation of arterial/venous domains, vascular morphogenesis, and sprouting angiogenesis. Genes Dev. 1999;13:295–306. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.3.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar HC, Lee B. Emerging paramyxoviruses: molecular mechanisms and antiviral strategies. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2011;13:e6. doi: 10.1017/S1462399410001754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett BD, Zeigler FC, Gu Q, Fendly B, Goddard AD, et al. Molecular cloning of a ligand for the eph-related receptor protein-tyrosine kinase htk. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:1866–1870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.6.1866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson MD, Romero MI, Lush ME, Lu QR, Henkemeyer M, et al. Ephrin-b3 is a myelin-based inhibitor of neurite outgrowth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:10694–10699. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504021102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergemann AD, Cheng HJ, Brambilla R, Klein R, Flanagan JG. Elf-2, a new member of the eph ligand family, is segmentally expressed in mouse embryos in the region of the hindbrain and newly forming somites. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:4921–4929. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.9.4921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergemann AD, Zhang L, Chiang MK, Brambilla R, Klein R, et al. Ephrin-b3, a ligand for the receptor ephb3, expressed at the midline of the developing neural tube. Oncogene. 1998;16:471–480. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop KA, Hickey AC, Khetawat D, Patch JR, Bossart KN, et al. Residues in the stalk domain of the hendra virus g glycoprotein modulate conformational changes associated with receptor binding. J Virol. 2008;82:11398–11409. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02654-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonaparte MI, Dimitrov AS, Bossart KN, Crameri G, Mungall BA, et al. Ephrin-b2 ligand is a functional receptor for hendra virus and nipah virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:10652–10657. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504887102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossart KN, Crameri G, Dimitrov AS, Mungall BA, Feng Y, et al. Receptor binding, fusion inhibition, and induction of cross-reactive neutralizing antibodies by a soluble g glycoprotein of hendra virus. J Virol. 2005;79:6690–6702. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.11.6690-6702.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossart KN, Geisbert TW, Feldmann H, Zhu Z, Feldmann F, et al. A neutralizing human monoclonal antibody protects african green monkeys from hendra virus challenge. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:105ra103. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossart KN, Tachedjian M, McEachern JA, Crameri G, Zhu Z, et al. Functional studies of host-specific ephrin-b ligands as henipavirus receptors. Virology. 2008;372:357–371. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossart KN, Wang LF, Eaton BT, Broder CC. Functional expression and membrane fusion tropism of the envelope glycoproteins of hendra virus. Virology. 2001;290:121–135. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossart KN, Zhu Z, Middleton D, Klippel J, Crameri G, et al. A neutralizing human monoclonal antibody protects against lethal disease in a new ferret model of acute nipah virus infection. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000642. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowden TA, Aricescu AR, Gilbert RJC, Grimes JM, Jones EY, et al. Structural basis of nipah and hendra virus attachment to their cell-surface receptor ephrin-b2. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008a;15:567–572. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowden TA, Crispin M, Harvey DJ, Aricescu AR, Grimes JM, et al. Crystal structure and carbohydrate analysis of nipah virus attachment glycoprotein: a template for antiviral and vaccine design. J Virol. 2008b;82:11628–11636. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01344-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowden TA, Crispin M, Harvey DJ, Jones EY, Stuart DI. Dimeric architecture of the hendra virus attachment glycoprotein: evidence for a conserved mode of assembly. J Virol. 2010a;84:6208–6217. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00317-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowden TA, Crispin M, Jones EY, Stuart DI. Shared paramyxoviral glycoprotein architecture is adapted for diverse attachment strategies. Biochem Soc Trans. 2010b;38:1349–1355. doi: 10.1042/BST0381349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucci C, Lütcke A, Steele-Mortimer O, Olkkonen VM, Dupree P, et al. Co-operative regulation of endocytosis by three rab5 isoforms. FEBS Lett. 1995;366:65–71. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00477-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrencik JE, Brooun A, Kraus ML, Recht MI, Kolatkar AR, et al. Structural and biophysical characterization of the ephb4*ephrinb2 protein-protein interaction and receptor specificity. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:28185–28192. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605766200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua KB. Epidemiology, surveillance and control of nipah virus infections in malaysia. Malays J Pathol. 2010;32:69–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua KB, Goh KJ, Wong KT, Kamarulzaman A, Tan PS, et al. Fatal encephalitis due to nipah virus among pig-farmers in malaysia. Lancet. 1999;354:1257–1259. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)04299-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan CA, Henkemeyer M. The sh2/sh3 adaptor grb4 transduces b-ephrin reverse signals. Nature. 2001;413:174–179. doi: 10.1038/35093123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crimeen-Irwin B, Ellis S, Christiansen D, Ludford-Menting MJ, Milland J, et al. Ligand binding determines whether cd46 is internalized by clathrin-coated pits or macropinocytosis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:46927–46937. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308261200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards CM, Mundy GR. Eph receptors and ephrin signaling pathways: a role in bone homeostasis. Int J Med Sci. 2008;5:263–272. doi: 10.7150/ijms.5.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eph Nomenclature Committee . Unified nomenclature for eph family receptors and their ligands, the ephrins. eph nomenclature committee. Cell. 1997;90:403–404. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80500-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erbar S, Diederich S, Maisner A. Selective receptor expression restricts nipah virus infection of endothelial cells. Virol J. 2008;5:142. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-5-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogarty R, Halpin K, Hyatt AD, Daszak P, Mungall BA. Henipavirus susceptibility to environmental variables. Virus Res. 2008;132:140–144. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Füller T, Korff T, Kilian A, Dandekar G, Augustin HG. Forward ephb4 signaling in endothelial cells controls cellular repulsion and segregation from ephrinb2 positive cells. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:2461–2470. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale NW, Baluk P, Pan L, Kwan M, Holash J, et al. Ephrin-b2 selectively marks arterial vessels and neovascularization sites in the adult, with expression in both endothelial and smooth-muscle cells. Dev Biol. 2001;230:151–160. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisbert TW, Daddario-DiCaprio KM, Hickey AC, Smith MA, Chan Y, et al. Development of an acute and highly pathogenic nonhuman primate model of nipah virus infection. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e10690. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgakopoulos A, Litterst C, Ghersi E, Baki L, Xu C, et al. Metalloproteinase/presenilin1 processing of ephrinb regulates ephb-induced src phosphorylation and signaling. EMBO J. 2006;25:1242–1252. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgakopoulos A, Xu J, Xu C, Mauger G, Barthet G, et al. Presenilin1/gamma-secretase promotes the ephb2-induced phosphorylation of ephrinb2 by regulating phosphoprotein associated with glycosphingolipid-enriched microdomains/csk binding protein. FASEB J. 2011;25:3594–3604. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-187856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerety SS, Anderson DJ. Cardiovascular ephrinb2 function is essential for embryonic angiogenesis. Development. 2002;129:1397–1410. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.6.1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh KJ, Tan CT, Chew NK, Tan PS, Kamarulzaman A, et al. Clinical features of nipah virus encephalitis among pig farmers in malaysia. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1229–1235. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200004273421701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillaume V, Aslan H, Ainouze M, Guerbois M, Wild TF, et al. Evidence of a potential receptor-binding site on the nipah virus g protein (niv-g): identification of globular head residues with a role in fusion promotion and their localization on an niv-g structural model. J Virol. 2006;80:7546–7554. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00190-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafner C, Becker B, Landthaler M, Vogt T. Expression profile of eph receptors and ephrin ligands in human skin and downregulation of epha1 in nonmelanoma skin cancer. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:1369–1377. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasebe F, Thuy NTT, Inoue S, Yu F, Kaku Y, et al. Serologic evidence of nipah virus infection in bats, vietnam. Emerging Infect Dis. 2012;18:536–537. doi: 10.3201/eid1803.111121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashiguchi T, Maenaka K, Yanagi Y. Measles virus hemagglutinin: structural insights into cell entry and measles vaccine. Front Microbiol. 2011a;2:247. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashiguchi T, Ose T, Kubota M, Maita N, Kamishikiryo J, et al. Structure of the measles virus hemagglutinin bound to its cellular receptor slam. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011b;18:135–141. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayman DTS, Suu-Ire R, Breed AC, McEachern JA, Wang L, et al. Evidence of henipavirus infection in west african fruit bats. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2739. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayman DTS, Wang L, Barr J, Baker KS, Suu-Ire R, et al. Antibodies to henipavirus or henipa-like viruses in domestic pigs in ghana, west africa. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e25256. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himanen J, Saha N, Nikolov DB. Cell-cell signaling via eph receptors and ephrins. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2007;19:534–542. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmberg J, Frisén J. Ephrins are not only unattractive. Trends Neurosci. 2002;25:239–243. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(02)02149-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homaira N, Rahman M, Hossain MJ, Epstein JH, Sultana R, et al. Nipah virus outbreak with person-to-person transmission in a district of bangladesh, 2007. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138:1630–1636. doi: 10.1017/S0950268810000695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper P, Zaki S, Daniels P, Middleton D. Comparative pathology of the diseases caused by hendra and nipah viruses. Microbes Infect. 2001;3:315–322. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(01)01385-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper PT, Ketterer PJ, Hyatt AD, Russell GM. Lesions of experimental equine morbillivirus pneumonia in horses. Vet Pathol. 1997a;34:312–322. doi: 10.1177/030098589703400407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper PT, Westbury HA, Russell GM. The lesions of experimental equine morbillivirus disease in cats and guinea pigs. Vet Pathol. 1997b;34:323–329. doi: 10.1177/030098589703400408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu VP, Hossain MJ, Parashar UD, Ali MM, Ksiazek TG, et al. Nipah virus encephalitis reemergence, bangladesh. Emerging Infect Dis. 2004;10:2082–2087. doi: 10.3201/eid1012.040701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi H, Kitamura T, Sekiguchi M, Homma MK, Kabuyama Y, et al. Involvement of ephb1 receptor/ephrinb2 ligand in neuropathic pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007;32:1592–1598. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318074d46a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kullander K, Croll SD, Zimmer M, Pan L, McClain J, et al. Ephrin-b3 is the midline barrier that prevents corticospinal tract axons from recrossing, allowing for unilateral motor control. Genes Dev. 2001;15:877–888. doi: 10.1101/gad.868901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunz TH, Braun de Torrez E, Bauer D, Lobova T, Fleming TH. Ecosystem services provided by bats. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1223:1–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb RA, Paterson RG, Jardetzky TS. Paramyxovirus membrane fusion: lessons from the f and hn atomic structures. Virology. 2006;344:30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B. Envelope-receptor interactions in nipah virus pathobiology. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1102:51–65. doi: 10.1196/annals.1408.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B, Ataman ZA. Modes of paramyxovirus fusion: a henipavirus perspective. Trends Microbiol. 2011;19:389–399. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Wang J, Hickey AC, Zhang Y, Li Y, et al. Antibodies to nipah or nipah-like viruses in bats, china. Emerging Infect Dis. 2008;14:1974–1976. doi: 10.3201/eid1412.080359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebl DJ, Morris CJ, Henkemeyer M, Parada LF. Mrna expression of ephrins and eph receptor tyrosine kinases in the neonatal and adult mouse central nervous system. J Neurosci Res. 2003;71:7–22. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim CC, Sitoh YY, Lee KE, Kurup A, Hui F. Meningoencephalitis caused by a novel paramyxovirus: an advanced mri case report in an emerging disease. Singapore Med J. 1999;40:356–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim CCT, Lee WL, Leo YS, Lee KE, Chan KP, et al. Late clinical and magnetic resonance imaging follow up of nipah virus infection. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr. 2003;74:131–133. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.1.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu NQ, Lossinsky AS, Popik W, Li X, Gujuluva C, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 enters brain microvascular endothelia by macropinocytosis dependent on lipid rafts and the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway. J Virol. 2002;76:6689–6700. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.13.6689-6700.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luby SP, Gurley ES, Hossain MJ. Transmission of human infection with nipah virus. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:1743–1748. doi: 10.1086/647951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luby SP, Rahman M, Hossain MJ, Blum LS, Husain MM, et al. Foodborne transmission of nipah virus, bangladesh. Emerging Infect Dis. 2006;12:1888–1894. doi: 10.3201/eid1212.060732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maar D, Harmon B. Cysteines in the stalk of the nipah virus g glycoprotein are located in a distinct subdomain critical for fusion activation. J Virol. 2012 doi: 10.1128/JVI.00076-12. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mäkinen T, Adams RH, Bailey J, Lu Q, Ziemiecki A, et al. Pdz interaction site in ephrinb2 is required for the remodeling of lymphatic vasculature. Genes Dev. 2005;19:397–410. doi: 10.1101/gad.330105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maréchal V, Prevost MC, Petit C, Perret E, Heard JM, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 entry into macrophages mediated by macropinocytosis. J Virol. 2001;75:11166–11177. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.22.11166-11177.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marianneau P, Guillaume V, Wong T, Badmanathan M, Looi RY, et al. Experimental infection of squirrel monkeys with nipah virus. Emerging Infect Dis. 2010;16:507–510. doi: 10.3201/eid1603.091346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marr D, Harmon B, Chu D, Schulz S, Aguilar HC, Lee B, Negrete ON. Cysteines in the stalk of the Nipah virus G glycoprotein are located in a distinct subdomain critical for fusion activation. J Virol. 2012 doi: 10.1128/JVI.00076-12. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marston DJ, Dickinson S, Nobes CD. Rac-dependent trans-endocytosis of ephrinbs regulates eph-ephrin contact repulsion. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:879–888. doi: 10.1038/ncb1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massé N, Ainouze M, Néel B, Wild TF, Buckland R, et al. Measles virus (mv) hemagglutinin: evidence that attachment sites for mv receptors slam and cd46 overlap on the globular head. J Virol. 2004;78:9051–9063. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.17.9051-9063.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathieu C, Pohl C, Szecsi J, Trajkovic-Bodennec S, Devergnas S, et al. Nipah virus uses leukocytes for efficient dissemination within a host. J Virol. 2011;85:7863–7871. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00549-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane R, Becker N, Field H. Investigation of the climatic and environmental context of hendra virus spillover events 1994–2010. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e28374. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer J, Helenius A. Vaccinia virus uses macropinocytosis and apoptotic mimicry to enter host cells. Science. 2008;320:531–535. doi: 10.1126/science.1155164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer S, Hafner C, Guba M, Flegel S, Geissler EK, et al. Ephrin-b2 overexpression enhances integrin-mediated ecm-attachment and migration of b16 melanoma cells. Int J Oncol. 2005;27:1197–1206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills JN, Alim ANM, Bunning ML, Lee OB, Wagoner KD, et al. Nipah virus infection in dogs, malaysia, 1999. Emerging Infect Dis. 2009;15:950–952. doi: 10.3201/eid1506.080453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mühlebach MD, Mateo M, Sinn PL, Prüfer S, Uhlig KM, et al. Adherens junction protein nectin-4 is the epithelial receptor for measles virus. Nature. 2011;480:530–533. doi: 10.1038/nature10639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mungall BA, Middleton D, Crameri G, Bingham J, Halpin K, et al. Feline model of acute nipah virus infection and protection with a soluble glycoprotein-based subunit vaccine. J Virol. 2006;80:12293–12302. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01619-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mungall BA, Middleton D, Crameri G, Halpin K, Bingham J, et al. Vertical transmission and fetal replication of nipah virus in an experimentally infected cat. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:812–816. doi: 10.1086/520818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahar N, Sultana R, Gurley ES, Hossain MJ, Luby SP. Date palm sap collection: exploring opportunities to prevent nipah transmission. Ecohealth. 2010;7:196–203. doi: 10.1007/s10393-010-0320-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negrete OA, Chu D, Aguilar HC, Lee B. Single amino acid changes in the nipah and hendra virus attachment glycoproteins distinguish ephrinb2 from ephrinb3 usage. J Virol. 2007;81:10804–10814. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00999-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negrete OA, Levroney EL, Aguilar HC, Bertolotti-Ciarlet A, Nazarian R, et al. Ephrinb2 is the entry receptor for nipah virus, an emergent deadly paramyxovirus. Nature. 2005;436:401–405. doi: 10.1038/nature03838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negrete OA, Wolf MC, Aguilar HC, Enterlein S, Wang W, et al. Two key residues in ephrinb3 are critical for its use as an alternative receptor for nipah virus. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e7. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noyce RS, Bondre DG, Ha MN, Lin LT, Sisson G, Tsao MS, Richardson CD. Tumor cell marker PVRL4 (nectin 4) is an epithelial cell receptor for measles virus. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002240. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson JG, Rupprecht C, Rollin PE, An US, Niezgoda M, et al. Antibodies to nipah-like virus in bats (pteropus lylei), cambodia. Emerging Infect Dis. 2002;8:987–988. doi: 10.3201/eid0809.010515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascall JC, Brown KD. Intramembrane cleavage of ephrinb3 by the human rhomboid family protease, rhbdl2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;317:244–252. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquale EB. Eph-ephrin bidirectional signaling in physiology and disease. Cell. 2008;133:38–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pernet O, Pohl C, Ainouze M, Kweder H, Buckland R. Nipah virus entry can occur by macropinocytosis. Virology. 2009;395:298–311. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaff D, Héroult M, Riedel M, Reiss Y, Kirmse R, et al. Involvement of endothelial ephrin-b2 in adhesion and transmigration of ephb-receptor-expressing monocytes. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:3842–3850. doi: 10.1242/jcs.030627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitulescu ME, Adams RH. Eph/ephrin molecules--a hub for signaling and endocytosis. Genes Dev. 2010;24:2480–2492. doi: 10.1101/gad.1973910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plowright RK, Field HE, Smith C, Divljan A, Palmer C, et al. Reproduction and nutritional stress are risk factors for hendra virus infection in little red flying foxes (pteropus scapulatus) Proc Biol Sci. 2008;275:861–869. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2007.1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radhakrishna H, Al-Awar O, Khachikian Z, Donaldson JG. Arf6 requirement for rac ruffling suggests a role for membrane trafficking in cortical actin rearrangements. J Cell Sci. 1999;112(Pt 6):855–866. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.6.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman MA, Hossain MJ, Sultana S, Homaira N, Khan SU, et al. Date palm sap linked to nipah virus outbreak in bangladesh, 2008. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2012;12:65–72. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2011.0656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockx B, Bossart KN, Feldmann F, Geisbert JB, Hickey AC, et al. A novel model of lethal hendra virus infection in african green monkeys and the effectiveness of ribavirin treatment. J Virol. 2010;84:9831–9839. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01163-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeed MF, Kolokoltsov AA, Albrecht T, Davey RA. Cellular entry of ebola virus involves uptake by a macropinocytosis-like mechanism and subsequent trafficking through early and late endosomes. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001110. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selvey LA, Wells RM, McCormack JG, Ansford AJ, Murray K, et al. Infection of humans and horses by a newly described morbillivirus. Med J Aust. 1995;162:642–645. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1995.tb126050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su Z, Xu P, Ni F. Single phosphorylation of tyr304 in the cytoplasmic tail of ephrin b2 confers high-affinity and bifunctional binding to both the sh2 domain of grb4 and the pdz domain of the pdz-rgs3 protein. Eur J Biochem. 2004;271:1725–1736. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suksanpaisan L, Susantad T, Smith DR. Characterization of dengue virus entry into hepg2 cells. J Biomed Sci. 2009;16:17. doi: 10.1186/1423-0127-16-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun P, Yamamoto H, Suetsugu S, Miki H, Takenawa T, et al. Small gtpase rah/rab34 is associated with membrane ruffles and macropinosomes and promotes macropinosome formation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:4063–4071. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208699200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan C, Chua K. Nipah virus encephalitis. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2008;10:315–320. doi: 10.1007/s11908-008-0051-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanimura N, Imada T, Kashiwazaki Y, Sharifah SH. Distribution of viral antigens and development of lesions in chicken embryos inoculated with nipah virus. J Comp Pathol. 2006;135:74–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpa.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatsuo H, Ono N, Tanaka K, Yanagi Y. Slam (cdw150) is a cellular receptor for measles virus. Nature. 2000;406:893–897. doi: 10.1038/35022579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenbroucke E, Mehta D, Minshall R, Malik AB. Regulation of endothelial junctional permeability. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1123:134–145. doi: 10.1196/annals.1420.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigant F, Lee B. Hendra and nipah infection: pathology, models and potential therapies. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2011;11:315–336. doi: 10.2174/187152611795768097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wacharapluesadee S, Boongird K, Wanghongsa S, Ratanasetyuth N, Supavonwong P, et al. A longitudinal study of the prevalence of nipah virus in pteropus lylei bats in thailand: evidence for seasonal preference in disease transmission. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2010;10:183–190. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2008.0105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HU, Chen ZF, Anderson DJ. Molecular distinction and angiogenic interaction between embryonic arteries and veins revealed by ephrin-b2 and its receptor eph-b4. Cell. 1998;93:741–753. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81436-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weise C, Erbar S, Lamp B, Vogt C, Diederich S, et al. Tyrosine residues in the cytoplasmic domains affect sorting and fusion activity of the nipah virus glycoproteins in polarized epithelial cells. J Virol. 2010;84:7634–7641. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02576-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson DG. How attraction turns to repulsion. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:851–853. doi: 10.1038/ncb1003-851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson MM, Hooper PT, Selleck PW, Westbury HA, Slocombe RF. Experimental hendra virus infectionin pregnant guinea-pigs and fruit bats (pteropus poliocephalus) J Comp Pathol. 2000;122:201–207. doi: 10.1053/jcpa.1999.0364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson MM, Hooper PT, Selleck PW, Westbury HA, Slocombe RF. A guinea-pig model of hendra virus encephalitis. J Comp Pathol. 2001;124:273–279. doi: 10.1053/jcpa.2001.0464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson MM, Torres-Velez FJ. Henipavirus: a review of laboratory animal pathology. Vet Pathol. 2010;47:871–880. doi: 10.1177/0300985810378648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong KT, Grosjean I, Brisson C, Blanquier B, Fevre-Montange M, et al. A golden hamster model for human acute nipah virus infection. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:2127–2137. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63569-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong KT, Shieh W, Kumar S, Norain K, Abdullah W, et al. Nipah virus infection: pathology and pathogenesis of an emerging paramyxoviral zoonosis. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:2153–2167. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64493-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu K, Rajashankar KR, Chan Y, Himanen JP, Broder CC, et al. Host cell recognition by the henipaviruses: crystal structures of the nipah g attachment glycoprotein and its complex with ephrin-b3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:9953–9958. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804797105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoneda M, Guillaume V, Ikeda F, Sakuma Y, Sato H, et al. Establishment of a nipah virus rescue system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:16508–16513. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606972103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young PL, Halpin K, Selleck PW, Field H, Gravel JL, et al. Serologic evidence for the presence in pteropus bats of a paramyxovirus related to equine morbillivirus. Emerging Infect Dis. 1996;2:239–240. doi: 10.3201/eid0203.960315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan J, Marsh G, Khetawat D, Broder CC, Wang L, et al. Mutations in the g-h loop region of ephrin-b2 can enhance nipah virus binding and infection. J Gen Virol. 2011a;92:2142–2152. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.033787-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan K, Hong T, Chen JJW, Tsai WH, Lin MT. Syndecan-1 up-regulated by ephrinb2/ephb4 plays dual roles in inflammatory angiogenesis. Blood. 2004;104:1025–1033. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan K, Jin YT, Lin MT. Expression of tie-2, angiopoietin-1, angiopoietin-2, ephrinb2 and ephb4 in pyogenic granuloma of human gingiva implicates their roles in inflammatory angiogenesis. J Periodont Res. 2000;35:165–171. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0765.2000.035003165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan P, Leser GP, Demeler B, Lamb RA, Jardetzky TS. Domain architecture and oligomerization properties of the paramyxovirus piv 5 hemagglutinin-neuraminidase (hn) protein. Virology. 2008;378:282–291. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan P, Swanson KA, Leser GP, Paterson RG, Lamb RA, et al. Structure of the newcastle disease virus hemagglutinin-neuraminidase (hn) ectodomain reveals a four-helix bundle stalk. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011b;108:14920–14925. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111691108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamudio-Meza H, Castillo AM, González-Bonilla C, Meza I. Rac1 and cdc42 gtpases cross-talk regulates formation of filopodia required for dengue virus type-2 entry into hmec-1 cells. J Gen Virol. 2009 doi: 10.1099/vir.0.014159-0. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C, Irie N, Takada Y, Shimoda K, Miyamoto T, et al. Bidirectional ephrinb2-ephb4 signaling controls bone homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2006;4:111–121. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer M, Palmer A, Köhler J, Klein R. Ephb-ephrinb bi-directional endocytosis terminates adhesion allowing contact mediated repulsion. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:869–878. doi: 10.1038/ncb1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]