Abstract

Pseudoterranova decipiens larva is a rare cause of anisakiasis. Indeed, prior to the present study, there had been only 12 reports of larval P. decipiens infection in the Republic of Korea. In June 2011, an anisakid larva, 32.1 mm in length and 0.88 mm in width, and finally identified as the third stage larva of P. decipiens owing to the presence of an intestinal cecum but lacking ventricular appendage, was discovered in a 61-year-old woman during the course of endoscopy executed as a part of routine physical examinations. The patient had eaten raw a rockfish 13 hr prior to the endoscopy, but showed no symptoms of anisakiasis. This paper is the 13th report of P. decipiens infection in Korea.

Keywords: Pseudoterranova decipiens, anisakiasis, endoscopy, rockfish

INTRODUCTION

Anisakiasis, a well-known disease occurring in humans, is caused by ingestion of anisakid larvae in dishes with raw marine fish and squids. Post-consumption, the third stage larvae can penetrate the stomach and intestinal walls, leading to such symptoms as stomach pain, fever, diarrhea, vomiting, or even, in cases of multiple infection, mental stupor [1,2]. Also, recently anisakid larvae have been implicated as a possible causative food allergen in adult patients presenting with urticaria, angioedema, anaphylaxis, and other maladies [3].

Most cases of human anisakiasis have been traced to the genus Anisakis, and the genus Pseudoterranova is the second most common anisakid found in humans [1]. The Republic of Korea has a longstanding tradition of raw fish consumption, and so it is not surprising that numerous Korean patients have been diagnosed with anisakiasis, most of those cases being Anisakis simplex [4]. As for Pseudoterranova, however, there have been only 12 confirmed cases in Korea [5]. In this paper, we report a case of human infection by P. decipiens larva, discovered in a routine physical examination.

CASE RECORD

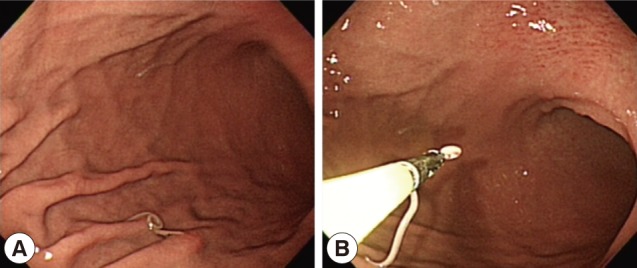

In June 2011, an anisakid larva was discovered in a 61-year-old woman during the course of endoscopy executed at Dankook University Hospital (Fig. 1). The laboratory findings were within the normal limits, except for a mild elevation of the eosinophil count (5.3%). She was living in Cheonan city, Chungcheongnam-do, and on an evening about 13 hr prior to her endoscopy, ate a rockfish (Sebastes sp.). The larva was immediately fixed in 10% formalin, and transferred to the Department of Parasitology, College of Medicine, Dankook University. It was cleaned in glycerin-alcohol, mounted with glycerin-jelly and observed under a light microscope. The larva was 32.1 mm in length and 0.88 mm in width. The mouth was surrounded by 3 lips, and the boring tooth was present. The esophagus was 2.4 mm in length, and was composed of long muscular and short ventricular parts.

Fig. 1.

Endoscopic findings of the patient. (A) A whitish worm is identified in the gastric mucosa. (B) The worm is being removed from the stomach using a biopsy forcep.

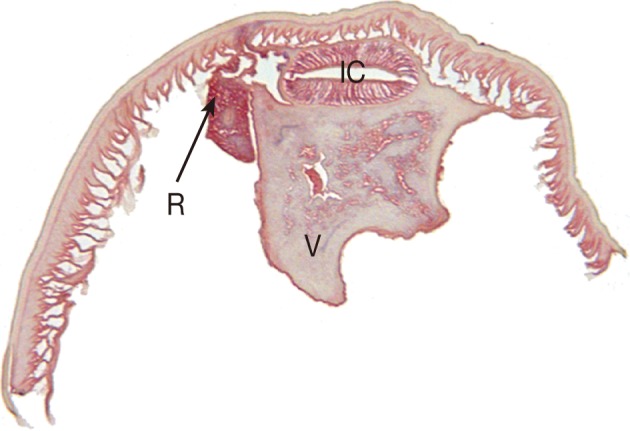

The intestinal cecum, confirmed by section of the anterior part of the worm, was 1.1 mm in length, stretching to the middle level of the ventriculus. The tail, 0.20 mm in length, was conical with a terminal mucron. The presence of an intestinal cecum without ventricular appendage was easily observed in the transverse section of the worm (Fig. 2). All of these findings readily identified the specimen as a third stage larva of Pseudoterranova decipiens. After removal of the larva, the patient returned home and followed up uneventfully.

Fig. 2.

Transverse section of the P. decipiens larva. Note that the intestinal cecum (IC), ventriculus (V), and renette cell (R) are seen.

DISCUSSION

As already noted, this case of P. decipiens infection is the 13th discovered in Korea. Since Anisakis type I larvae have been implicated in most cases of human anisakiasis in Korea, other anisakid larvae such as Pseudoterranova and Contracaecum frequently have been overlooked [6]. In fact, human infections with Pseudoterranova spp. is far from rare in northern Japan, amounting to 769 cases by the mid-1990s [7] and 7 cases of P. decipiens have occurred in Chile [8,9]. Recently, P. decipiens was classified, by the molecular method, into 5 sibling species, i.e., P. decipiens sensu stricto, P. azarasi, P. cattani, P. krabbei, and P. bulbosa [10]. Unfortunately, whereas multiple infections of anisakid larvae are possible [2], most patients have been singly infected, which fact has hindered application of the molecular technique, as in the present case. Although molecular identification often is unavailable, comprehensive and detailed understanding of anisakid fauna can be attained through morphology-based genus-level identification.

The most important structure of anisakid larvae in species identification is their esophagointestinal morphologies with the corresponding measurements. Anisakis spp. larvae have a simple and straight arranged digestive tract, i.e., muscular esophagus, ventriculus, and intestine. On the other hand, in Pseudoterranova spp. larvae, the presence of an intestinal cecum without ventricular appendage is the key to distinguish from Contracecum spp. larvae [5]. The present worm could be diagnosed as a third stage larva in consideration of the fact that the cecum reached beyond the one-third level of the ventriculus anteriorly, along with the presence of a mucron at the posterior end [5].

Curiously, the patient whose case prompted this study did not complain of any symptoms arising from P. decipiens infection, that can include allergic symptoms. Most Japanese patients with Pseudoterranova spp. had acute or subacute abdominal pain [9], and Korean patients have complained of epigastic pain [3,5,11]. However, P. decipiens larvae, as seen in a Chilean case [8], can be expelled from the mouth in the absence of gastric symptoms. The sensation of a foreign body between the teeth has been the chief complaint of some infected patients [12]. Finally, it has been suggested that P. decipiens larvae are less invasive than A. simplex [8], though it should be noted that the varied symptoms of P. decipiens may result from different responses of individual hosts or different pathogenicity of Pseudoterranova spp.

Although Pseudoterranova spp. larvae exist in very small numbers compared with other Anisakis spp., they have been traced to more than 30 marine fish species such as cod, pollock, halibut, and flatfish worldwide [13]. However, they have never been recovered from host fish caught in Korea. For example, the larvae recovered from the yellow corvina (Pseudosciaena manchurica), have been Anisakis simplex (80.4%), Contracecum spp. (15.5%), and other unidentifiable species (3.9%) [14]. Nonetheless, total 13 cases of P. decipiens infection, including the present case have been diagnosed in Korea. This reflects the fact that P. decipiens larvae must be distributed in fish hosts caught in Korea. Certainly in Korea, where raw seafood, as already noted, is a popular feature of the cuishine, human infection resulting from ingestion of P. decipiens larvae, which reside primarily in fish muscle [15], could be discovered much more. Further studies on Pseudoterranova spp. infection, its distribution and epidemiology, along with molecular examinations of Pseudoterranova larva, are required.

References

- 1.Chai JY, Murrell KD, Lymbery A. Fish-borne parasitic zoonoses: status and issues. Int J Parasitol. 2005;35:1233–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2005.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Noh JH, Kim BJ, Kim SM, Ock MS, Park MI, Goo JY. A case of acute gastric anisakiasis provoking severe clinical problems by multiple infection. Korean J Parasitol. 2003;41:97–100. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2003.41.2.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choi SJ, Lee JC, Kim MJ, Hur GY, Shin SY, Park HS. The clinical characteristics of Anisakis allergy in Korea. Korean J Intern Med. 2009;24:160–163. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2009.24.2.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Im KI, Shin HJ, Kim BH, Moon SI. Gastric anisakiasis cases in Cheju-do, Korea. Korean J Parasitol. 1995;33:179–186. doi: 10.3347/kjp.1995.33.3.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu JR, Seo M, Kim YW, Oh MH, Sohn WM. A human case of gastric infection by Pseudoterranova decipiens larva. Korean J Parasitol. 2001;39:193–196. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2001.39.2.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seol SY, Ok SC, Pyo JS, Kim IH, Lee SH, Chung JM, Choi HJ, Jung SJ, Sohn WM. Twenty cases of gastric anisakiasis caused by Anisakis type I larva. Korean J Gastroenterol. 1994;26:17–24. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ishikura H. Anisakiasis. 2. Clinical pathology and epidemiology. Prog Med Parasitol Japan. 2003;8:451–473. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mercado R, Torres P, Muñoz V, Apt W. Human infection by Pseudoterranova decipiens (Nematoda, Anisakidae) in Chile: report of seven cases. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2001;96:653–655. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762001000500010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arizono N, Miura T, Yamada M, Tegoshi T, Onishi K. Human infection with Pseudoterranova azarasi roundworm. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:555–556. doi: 10.3201/eid1703.101350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee IH, Jang S, Lee CY, Park JS, Lee HJ, Kim HJ, Choi DS, Chun DC, Kim JS, Sohn WM. A case of human infection of the larvae from Pseudoterranova decipiens. Korean J Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;18:732–736. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sohn WM, Seol SY. A human case of gastric anisakiasis by Pseudoterranova decipiens larva. Korean J Parasitol. 1994;32:53–56. doi: 10.3347/kjp.1994.32.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Torres P, Jercic MI, Weitz JC, Dobrew EK, Mercado RA. Human pseudoterranovosis, an emerging infection in Chile. J Parasitol. 2007;93:440–443. doi: 10.1645/GE-946R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bristow GA, Berland B. On the ecology and distribution of Pseudoterranova decipiens (Nematoda: Anisakidae) in an intermediate host, Hippoglossoides platessoides, in Northern Norwegian waters. Int J Parasitol. 1992;22:203–208. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(92)90102-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chai JY, Chu YM, Sohn WM, Lee SH. Larval anisakids collected from the yellow corvina in Korea. Korean J Parasitol. 1986;24:1–11. doi: 10.3347/kjp.1986.24.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oshima T. Anisakiasis: is the sushi bar guilty? Parasitol Today. 1987;3:44–49. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(87)90212-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]