Abstract

This mini-review describes recent epidemiological trends in cysticercosis and taeniasis in Japan. Some of the topics discussed herein were presented at the first symposium on "Current perspectives of Taenia asiatica researches", that was held in Osong in Chungbuk Province, South Korea, in October 2011 and organized by Prof. K. S. Eom, Chungbuk National University School of Medicine. To better understand the trends in the occurrence of cysticercosis and taeniasis in Japan, clinical cases reported in 2005 have been updated. In addition, the current status of Taenia asiatica infections successively occurring in Japan since 2010 is also discussed.

Keywords: Taenia solium, Taenia asiatica, Taenia saginata, taeniasis, cysticercosis, Japan

INTRODUCTION

Cysticercosis, a parasitic disease caused by Taenia solium cysticercus, is one of the important parasitic diseases. Neurocysticercosis (NCC) is accepted to refer to cysts in the central nerve system, including the parenchyma and ventricles of the brain and the spinal cord. Subcutaneous cysticercosis (SCC) is used for the cysticercosis presenting the form of firm, mobile nodules, mainly in the soft tissues and muscles of on the trunk and extremities. NCC is clinically more serious than SCC because of the severity of the neurologic symptoms, such as epileptic seizures and paralysis that can result from infection. The disease constitutes a major public health problem in many parts of the world, including China, Southeast Asia, India, sub-Saharan Africa, and Latin America [1]. Cysticercosis has also become an important parasitic disease in developed countries, such as the United States, particularly in California and other states with a large immigrant population [2]. In Japan, although T. solium cysticercosis/taeniasis was endemic to the Okinawa region in southern Japan 50-60 years ago [3,4], the disease is no longer endemic in the area. Nonetheless, sporadic cases of cysticercosis have been reported in Japan, primarily among Japanese returning from abroad and foreigners coming to Japan (Table 1) [5].

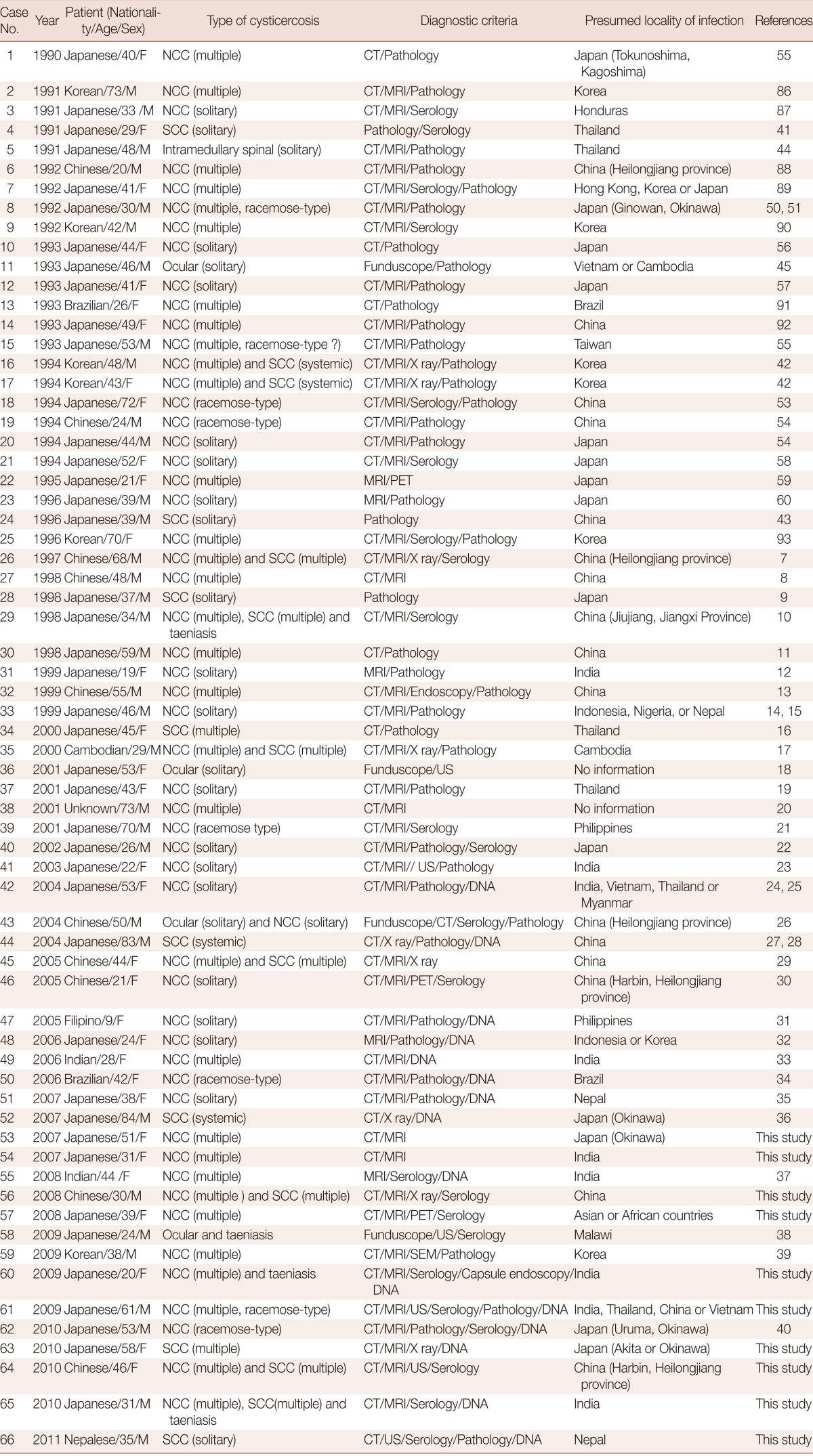

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical data for cysticercosis cases reported in Japan (1990-2011)

Conversely, taeniasis, which is caused by infection with the adult tapeworm of T. solium or Taenia saginata, occurs worldwide, except in countries where people do not eat pork and beef for religious reasons [1]. Taeniasis caused by Taenia asiatica is restricted to countries in Asia, including South Korea, China, Taiwan, the Philippines, Vietnam, Thailand, Indonesia, and Japan [6]. In Japan, sporadic cases of taeniasis have been reported and most of them were caused by infection with T. saginata and were imported cases until T. asiatica infections were confirmed in 2010 (Table 2). Compared to cysticercosis, taeniasis is innocuous or asymptomatic, with most patients presenting with slight intestinal illness and mental discomfort due to persistent expulsion of the proglottids.

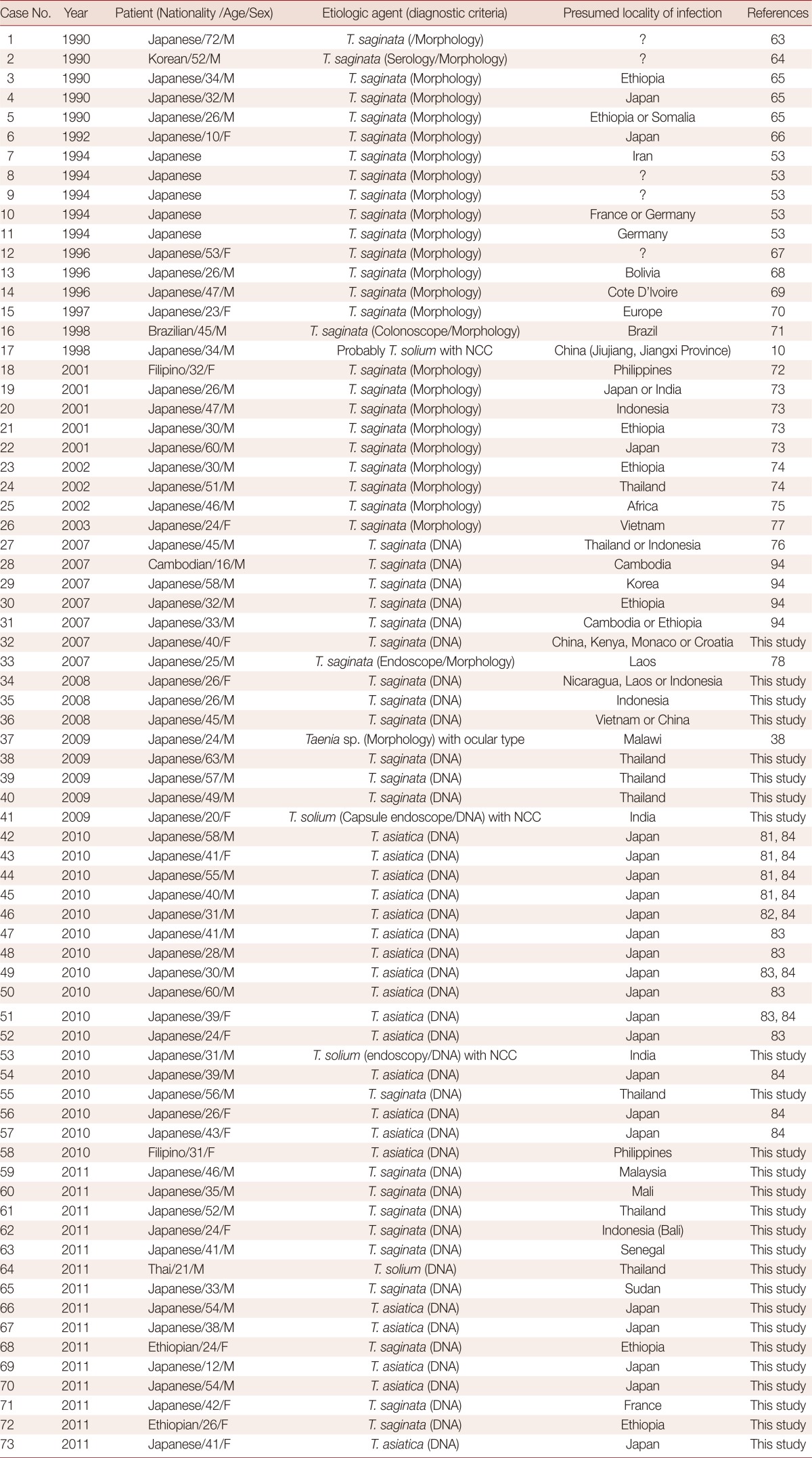

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical data for taeniasis reported in Japan (1990-2011)

In Japan, the "Ordinance for Enforcement of the Food Sanitation Act" based on the Food Sanitation Law stipulates that food-borne parasitic diseases such as cysticercosis and taeniasis be treated as cases of food poisoning and that authorities be notified of their occurrence immediately. However, because parasitic diseases have never reported based on the law, it is not possible to accurately estimate the incidence of cysticercosis/taeniasis in Japan. Therefore, the author previously examined the epidemiological trends in cysticercosis and taeniasis based on clinical cases in Japan published in scientific journals [5]. Since then, new cases of cysticercosis and taeniasis have been reported and several cases of cysticercosis have been newly diagnosed in our department. The Department of Parasitology at the National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Tokyo routinely performs diagnostic tests requested for parasitic diseases from domestic and foreign medical institutions, and cysticercosis and taeniasis also are acceptable for diagnosis.

The purpose of this article is to overview the current status of cysticercosis/taeniasis in Japan and to update the data that was reported in 2005 [5] based on the cases cited in PubMed (National Library of Medicine) and Japana Centra Revuo Medicina as well as cases diagnosed in our department over the last 5 years (2007-2011).

CLINICAL CASES

Cysticercosis

According to Nishiyama and Araki [4], as many as 389 cases of cysticercosis were reported in Japan from 1908 to 1997. However, 24 cases reported between 1943 and 1979 were not included in the study. Furthermore, 41 cases, including 10 cases diagnosed by our department, have been newly confirmed between 1997 and 2011 (cases 26-66 in Table 1) [7-40]. Taken together, this gives a total of 454 cysticercosis cases that have been reported in Japan between 1908 and 2011. Table 1 shows 66 of the cysticercosis cases that have been reported over the last 22 years (1990-2011) along with cases confirmed by our department between 2007 and 2011.

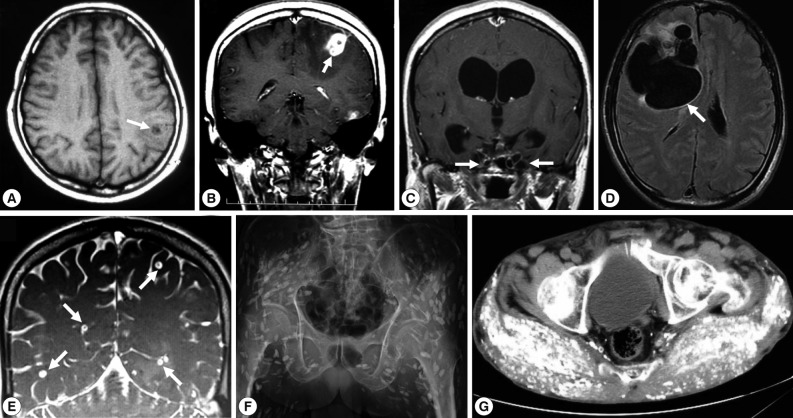

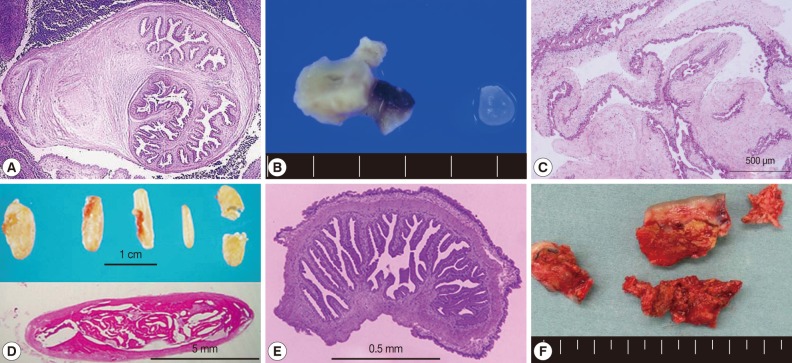

Of these 66 cases, 54 (66.7%) were NCC; NCC with multiple cysts (28/54, 51.9%; Fig. 1E) was more frequent than NCC with a solitary cyst (13/54, 33.5%; Fig. 1A, B and Fig. 2A, B, E). Between 1990 and 2011, total 17 cases of SCC were reported as cases 4 [41], 16-17 [42], 24 [43], 26 [7], 28 [9], 29 [10], 34 [16], 35 [17], 44 [27,28], 45 [29], 52 [36], 56, 63, 64, 65, and 66. Two of them were systemic intramuscular cysticercosis with numerous calcified cysts; cases 44 [27,28] and 52 [36] (Fig. 1F, G; Fig. 2D, F). Very rarely, intramedullary cysticercosis in case 5 [44] and ocular cysticercosis in cases 11 [45], 36 [18], 43 [26], and 58 [38] have also been reported. Ten cases of NCC with either SCC or ocular cysticercosis were reported in cases 16-17 [42], 26 [7], 29 [10], 35 [17], 43 [26], 45 [29], 56 , 64, and 65 (Table 1). More interestingly, dual infection of cysticercosis and taeniasis was observed in 4 cases; 29 [17], 58 [51], 60, and 65 (Table 1). Furthermore, the adult tapeworm in case 41 was observed in the small intestine using capsule endoscopy to confirm the presence of the adult worm (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Imaging findings of selected cysticercosis cases. (A) plain CT image showing a solitary lesion at the left occipitoparietal area (case 48 [32], courtesy of Prof. H. Matsuoka). (B) MRI showing one of multiple cystic lesions in the left frontal and temporal lobes (case 49 [33]). (C) MRI showing a rasemose-type lesion at the basal cistern (case 50 [34], courtesy of Dr. T. Oda). (D) MRI FLAIR findings showing a giant and multilobulated mass in the subarachnoidal spaces of the right frontal lobe (case 62 [40], courtesy of Dr. S. Shiiki). (E) Cisterography showing multiple cysts in the brain (case 60, courtesy of Prof. A. Chiba). (F) X-ray findings showing typical rice grain calcifications in the muscles of buttocks and lower extremity (case 44 [27, 28], courtesy of Dr. T. Nagase). (G) CT findings showing numerous calcified cysts in muscles of the of the buttocks (case 52 [36], courtesy of Dr. M. Tsuda).

Fig. 2.

Histopathologic findings of cystic lesions from cysticercosis patients. (A) A cellulose-type cysticercus characterized by rabyrinth-like structure (case 40 [22], courtesy of Dr. S. Matsunaga). (B) and (E) A resected lesion and a cellulose-type cysticercus (case 48 [32], courtesy of Prof. H. Matsuoka). (C) Racemose-type cysticercus characterized by complicated cystic walls (case 62 [40], courtesy of Dr. S. Shiiki). (D) SCC showing typical rice grain calcifications in the muscles of buttocks and lower extremity and the section of the calcified lesion (case 44 [27, 28], courtesy of Dr. T. Nagase). (F) Surgically removed calcified lesions (case 52 [36], courtesy of Dr. Tsuda). Sections (A, C , D, and E) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

Cysticercosis diagnosis is generally performed by imaging, serologic, and histopathologic examinations. In our department, molecular identification of the etiologic agents is routinely performed, if surgically removed materials are available [46-48]. Indeed, the usefulness of molecular methods for diagnosing the causative agents has successfully been demonstrated by the identification of 2 genotypes of T. solium cysticercus as well as confirmation of the agents in paraffin-embedded sections [24,25,28,31,33-35,37,40]. In addition, the localities where the patients were infected can also be inferred based on the DNA sequences of the causative agents [32,49].

In SCC, X-ray examinations have revealed the presence of rod-like, scattered, calcified lesions in the soft tissues of the extremities (Fig. 1F, G; Fig. 2D, F). These calcified cysts have histopathologically been confirmed to be T. solium in cases 16-17 [42], 26 [7], 52 [36], and 44 [27,28] (Fig. 2A, C, E).

Two types of T. solium cysticercus, cellulose- and racemose-types, are known to exist. The cellulose-type cysticercus is characterized by a single bladder measuring 3 to 18 mm in diameter with an invaginated scolex and primarily found in the cerebral parenchyma and musculature. The racemose-type presents as large multilobulated cystic lesions lacking a scolex and appears to prefer the cisternal and ventricular systems or subarachnoid space [2]. Indeed, the racemose-type cysticercus is frequently found in the subarachnoidal spaces as multilobulated lesions (Fig. 1C, D). Although cysticercosis due to racemose-type T. solium cysticercus is relatively rare, 8 cases have been documented in Japan in cases 8 [50,51], 15 [52], 18 [53], 19 [54], 39 [21], 50 [34], 61, and 62 [40] (Table 1; Fig. 1C, D; Fig. 2C). Of these, mitochondrial DNA analysis using histopathologic sections revealed that etiologic T. solium was the Asian genotype in 3 cases, 50 [32], 61, and 62 [40], and American/African genotype in case 50 [34] (Table 1). The racemose-type cysticercus is considered to be an aberrant, multilobular, non-viable T. solium cysticercus, possibly the degenerated form of a cysticercus in the basal subarachnoid space. Molecular analysis using formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded histopathologic specimens has proved that the racemose-type cysticercus is T. solium in cases 50 [34], 61, and 62 [40].

Most of the cysticercosis cases in Japan are imported cases, meaning that the patients either lived in or visited countries where cysticercosis and taeniasis are still endemic, and where they are presumed to have been exposed to T. solium eggs. However, 13 cases have suggested that infection occurred within Japan (cases 1 [55], 8 [50,51], 10 [56], 12 [57], 20 [54], 21 [58], 22 [59], 23 [60], 28 [9], 40 [22], 52 [36], 53, and 62 [40]. NCC was diagnosed by imaging findings (Fig. 1), serology, histopathology (Fig. 2A, C, D, E), and molecular analysis.

Taeniasis

Table 2 shows 73 clinical taeniasis case reports that have been published in journals between 1990 and 2011 and diagnosed by our department between 2007 and 2011. In addition to these, 26 cases have been reported [61,62]. The most commonly encountered taeniasis cases were T. saginata infections and 48 cases (65.8%) have been confirmed to date (Table 2). Of these 48 cases, 45 were imported cases [63-78]. Although the route of infection is unknown, the possibility also exists that 4 of these cases may be attributable to domestic infections; cases 4 [65], 6 [66], 19 [73], and 22 [73]. T. solium taeniasis is extremely rare in Japan and only 1 case was reported in Okinawa in 1988 [79]. However, taeniasis solium cases with either NCC, SCC, or ocular cysticercosis have been confirmed, and all these were imported in cases 29 [10], 58 [38], 60, and 65 (Table 1) and cases 17 [10], 41, 53, and 64 (Table 2). Taeniasis caused by T. asiatica has been also recently successively confirmed in Japan and this will be discussed in the following chapter.

Taeniasis is usually diagnosed based on proglottid morphology. However, since T. saginata, T. solium, and T. asiatica are all morphologically similar, it is not always possible to accurately differentiate them. As a result, more reliable molecular diagnoses are currently employed to differentiate between taeniasis infections in our department [46-48]. Most recently, T. solium tapeworms have been observed in the small intestine using capsule endoscopy in cases 41 [23] and 53.

CURRENT STATUS OF T. ASIATICA INFECTION IN JAPAN

Although T. asiatica was not previously considered to occur in Japan [5], retrospective molecular analyses of proglottids revealed that 2 T. asiatica infections occurred in Tottori Prefecture on Honshu Island, Japan, in 1968 and 1996 [6]. Unfortunately, it is unknown whether the 2 Japanese cases were domestic infections or imported cases. As the number of Japanese travelers visiting Asian countries has increased, so too has the number of people from other Asian countries visiting Japan. This may mean that the likelihood of encountering cases of imported T. asiatica is increasing. Surprisingly, from June 2010 to December 2011, an increasing number of human cases with taeniasis have been diagnosed in the Kanto region, including Tokyo and the neighboring 5 prefectures (Gumma, Tochigi, Saitama, Chiba, and Kanagawa) in central Honshu [80-84]. Of 31 taeniasis cases, 20 were attributed to T. asiatica. Taenia asiatica tapeworms were identified based on nucleotide sequence analysis of the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 gene [25] and allelic analysis of the 2 nuclear genes for elongation factor 1-α and ezrin-radixin-moesin-like protein genes [85].

Nineteen out of 20 patients infected with T. asiatica were Japanese nationals residing in the Kanto area and 1 was a Filipino woman living in same area (Tochigi). Fifteen patients stated that they frequently ate raw pig liver (sashimi). Sixteen had never been overseas or, if they had undertaken any international travel, they traveled to countries where T. asiatica is not endemic. The infection in the Filipino woman who has returned to the Philippines several times was also considered to have been occurred in Japan.

The occurrence of taeniasis due to T. asiatica infection is thus considered to have occurred within Japan by the following reasons: i) most of the patients had never been overseas or traveled to areas where T. asiatica is not endemic, ii) most patients had histories of eating raw pig liver, iii) based on interviews with patients and meat inspectors, pigs that had been produced and slaughtered in the Kanto region were strongly suspected to be possible sources of infection, iv) although Japan imports pork from Canada, Mexico, and Europe, no raw pig liver is imported from these countries. At present, the reasons why T. asiatica infections successively occurred in the Kanto region, a region within which the disease was not reported previously, have not yet been satisfactorily clarified. Considering that patients have occurred now, it is possible that the workers and pigs on farms in the Kanto region currently constitute the T. asiatica reservoirs responsible for these infections. We have been investigating the prevalence of T. asiatica metacestodes in pigs from these farms in collaboration with local meat inspection centers. In addition, we have also disseminated information describing precautions against T. asiatica infections in Infectious Agents Surveillance Reports (http://idsc.nih.go.jp/iasr/32/374/kj3741.html) published by the Infectious Diseases Information Center at the National Institute of Infectious Diseases [80-84].

CONCLUSIONS

It is expected that cysticercosis and taeniasis will primarily be detected as imported cases with the increasing numbers of Japanese travelers to foreign countries where these diseases are endemic or visitors from these areas increase. The occurrence of human infections due to T. asiatica is currently restricted to the Kanto region in Japan, and the origins of infection have not yet been clarified. Thus, further occurrence of the disease is likely to occur, medical practitioners should be aware of the importance accurately identifying the causative agent responsible for infection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author thanks Prof. Keeseon S. Eom and Prof. Jong-Yil Chai for their initiation to submit a review paper. The author also thanks Prof. H. Matsuoka, Prof. A. Chiba, Drs. T. Oda, S. Shiiki, T. Nagase, M. Tsuda, and S. Matsunaga, for providing imaging pictures and pathology specimens. Drs. Y. Morishima and H. Sugiyama are thanked for their valuable discussions of clinical cases, and M. Muto is also acknowledged for her technical assistance with molecular and serologic examinations of cysticercosis and taeniasis cases. The study was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan (H20-22-Shinko-Ippan-016 and H23-Shinko-Ippan-014) and from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (23650602).

References

- 1.García HH, Gonzalez AE, Evans CA, Gilman RH Cysticercosis Working Group in Peru. Taenia solium cystericercosis. Lancet. 2003;362:547–556. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14117-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.White AC., Jr Neurocysticercosis: Updates on epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Ann Rev Med. 2000;51:187–206. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.51.1.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Araki T. Current trend of cerebral cysticercosis in Japan. Clin Parasitol. 1994;5:12–24. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nishiyama T, Araki T. Cysticercosis cellulosae: Clinical features and epidemiology. In: Otsuru M, Kamegai S, Hayashi S, editors. Progress of Medical Parasitology in Japan. Vol. 8. Tokyo, Japan: Meguro Parasitological Museum; 2003. pp. 281–292. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamasaki H, Sako Y, Nakao M, Nakaya K, Ito A. Research on cysticercosis and taeniasis in Japan. In: Ito A, Wen H, Yamasaki H, editors. Taeniasis/Cysticercosis and Echinococcosis in Asia, Asian Parasitology. Vol. 2. Federation of Asian Parasitologists; 2005. pp. 6–36. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eom KS, Jeon HK, Rim HJ. Geographical distribution of Taenia asiatica and related species. Korean J Parasitol. 2009;47:S115–S124. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2009.47.S.S115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okabe K, Tsunoda M, Irie H, Koike H, Yoshino Y, Tsuji M. A case of cerebral cysticercosis with facial spasm showing a change in MRI abnormalities in a short time course. J Kyorin Med Soc. 1997;28:175–179. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Niijima K. MRI of cerebral cysticercosis. Shinkei Naika (Neurol Med) 1998;48:202–203. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matsushima H, Hatamochi A, Shinkai H, Shimizu M, Hatsushika R. A case of subcutaneous cysticercosis. J Dermatol. 1998;25:438–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1998.tb02431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okada S, Kikuchi S, Takeda A, Ootani K, Saiga T, Kobayashi M, Niimura M, Yamanouchi N, Kodama K, Sato T. A case of neurocysticercosis successfully treated with praziquantel. Seishinka Chiryogaku. 1998;13:345–351. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamakawa Y, Tashima T. Intraventricular cysticercosis diagnosed by histology of small fragment floating in the shunt tube. No Shinkei Geka Sokuho. 1998;8:833–837. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohsaki Y, Matsumoto A, Miyamoto K, Kondoh N, Araki K, Ito A, Kikuchi K. Neurocysticercosis without detectable specific antibody. Intern Med. 1999;38:67–70. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.38.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hatano T, Tsukahara T, Araki K, Kawakami O, Goto K, Okamoto E. A case of neurocysticercosis with multiple intraparenchymal and intraventricular cysts. No Shinkei Geka. 1999;27:335–339. (in Japanese) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ito A, Nakao M, Ito Y, Yuzawa I, Morishima H, Kawano N, Fujii K. Neurocysticercosis case with a single cyst in the brain showing dramatic drop in specific antibody titers within 1 year after curative surgical resection. Parasitol Int. 1999;48:95–99. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5769(99)00005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yuzawa I, Kawano N, Suzuki S, Fujii K, Ito Y. A case of solitary cerebral cysticercosis. Jpn J Neurosurg. 2000;9:364–369. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miura H, Itoh Y, Kozuka T. A case of subcutaneous cysticercosis (Cysticercus cellulosae cutis) J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:538–540. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2000.106513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sugiyama M, Okada T, Higuchi H, Yabe Y, Kobayashi N, Teramoto A. A case of neurocysticercosis presenting as focal seizure. No Shinkei Geka. 2000;28:807–810. (in Japanese) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kataoka H, Yamada T, Tsumura T, Kawamura H, Takenaka H, Maeno T, Mano T, Takahashi T. A case of presumed ocular cysticercosis. Ganka Rinsho Iho. 2001;95:605–606. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsuda M, Shimizu K, Shimizu Y, Hattori T, Tabata K. A case of neurocysticercosis with versive seizures as an initial symptom. Intern Med. 2001;87:405–407. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miyagami M. Cerebral imaging diagnosis CT, MRI. Modern Physician. 2001;21:1576–1581. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakajima M, Tashima K, Hirano T, Nakamura-Uchiyama F, Nawa Y, Uchino M. A case of neurocysticercosis suggestive of a reinfection, 20 years after the initial onset. Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 2002;42:18–23. (in Japanese) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsunaga S, Asada H, Shuto T, Hamada K, Inomori S, Kawamura S, Hamada A, Okuzawa E. A case of solitary neurocysticercosis of unknown transmission route. No Shinkei Geka. 2002;30:1223–1228. (in Japanese) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mori Y, Kobayashi T, Kida Y. A case of neurocysticercosis removed successfully surgically. Jpn J Neurosurg (Tokyo) 2003;12:191–195. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamasaki H, Ito A, Matsunaga S, Yamamura K, Chang CC, Kawamura S. A case of neurocysticercosis caused by Taenia solium Asian genotype confirmed by mitochondrial gene analysis of paraffin-embedded specimen. Clin Parasitol. 2003;14:77–80. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamasaki H, Matsunaga S, Yamamura K, Chang CC, Kawamura S, Sako Y, Nakao M, Nakaya K, Ito A. Solitary neurocysticercosis caused by Asian genotype of Taenia solium confirmed by mitochondrial DNA analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:3891–3893. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.8.3891-3893.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harada Y, Naoi N, Nawa Y, Harada K. A case of zoonotic infection by Cysticercus cellulosae. Jpn J Clin Ophthalmol. 2004;58:1985–1988. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nagase T, Kiyoshige Y, Suzuki M. A case of obsolete systemic cysticercosis cellulosae. Clin Parasitol. 2004;15:24–26. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamasaki H, Nagase T, Kiyoshige Y, Suzuki M, Nakaya K, Itoh Y, Sako Y, Nakao M, Ito A. A case of intramuscular cysticercosis diagnosed definitively by mitochondrial DNA analysis of extremely calcified cysts. Parasitol Int. 2006;55:127–130. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2005.11.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matsushita T, Tanaka C, Sakoh K, Mizobuchi M, Nihei A, Abe T, Seo Y, Murakami N. Neurocysticercosis - case report. Hokkaido Noshinkei Shikkan Inst Journal. 2005;15:35–39. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsumoto L, Ubano M, Uesaka Y, Kunimoto M, Kawanaka M. A case of neurocysticercosis diagnosed with positron emission tomography (PET) Shinkei Naika (Neurol Med) 2005;63:473–476. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamasaki H, Nakao M, Sako Y, Nakaya K, Ito A. Molecular identification of Taenia solium cysticercus genotype in the histopathological specimens. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2005;36(suppl 4):131–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsuoka H, Gomi H, Kanai N, Gomi A, Kanda M, Yamasaki H, Sako Y, Ito A. A case of solitary neurocysticercosis lacking elevation of specific antibodies. Clin Parasitol. 2006;17:102–106. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamasaki H, Sako Y, Nakao M, Ito A, Nakaya K. Taenia solium cysticercosis cases diagnosed by mitochondrial DNA analysis of paraffin-embedded specimens. Clin Parasitol. 2006;17:134–137. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oda T, Kikuchi B, Hoshino T, Koide A, Yoshimura J, Nishiyama K, Mori H. A case of hydrocephalus with stalactitic change of ventricular wall. Niigata Med J. 2006;120:115. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ishikawa E, Komatsu Y, Kikuchi K, Yamasaki H, Kimura H, Osuka S, Tsurubuchi T, Ito A, Matsumura A. Neurocysticercosis as solitary parenchymal lesion confirmed by mitochondrial deoxyribonucleic acis sequence analysis - case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2007;47:40–44. doi: 10.2176/nmc.47.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsuda M, Mine R, Kiyuna M, Yamasaki H, Ito A. A case of subcutaneous cysticercosis with multiple calcified cysts in the gluteal region. J Jpn Plastic Reconst Surg. 2007;27:381–385. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maeda T, Fujii T, Odawara T, Iwamoto A, Sako Y, Ito A, Yamasaki H. A reactivation case of neurocysticercosis with epithelial granuloma suspected by serology and confirmed by mitochondrial DNA analysis. Clin Parasitol. 2008;19:150–152. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 38.Masuda T, Yamaji H, Shiragami C, Fukuda K, Ogaki S, Harada M, Kagei N, Shiraga F. A case of intraocular cysticercosis treated by vitreous surgery. Jpn J Clin Ophthalmol. 2009;63:303–306. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 39.Komuro T, Okamoto S, Nitta T. A case of neurocysticercosis. No Shinkei Geka Sokuho. 2009;19:1072–1076. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamasaki H, Sugiyama H, Morishima Y, Ohmae H, Shiiki S, Okuyama K, Kunishima F. A case of neurocysticercosis caused by racemose-type Taenia solium cysticercus. Clin Parasitol. 2010;21:29–32. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sato T, Kunishi K, Kameyama A, Takano T, Ota N. A case of cysticercosis cellulosae hominis. Inter Med. 1991;68:190–192. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kuboyama K, Oku K, Seto T, Higasa S, Kimoto K, Akagi K, Iseki M. Radiological findings in two cases of cerebral cysticercosis. Clin Parasitol. 1994;5:153–156. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hatsushika R, Umemura S, Ito J, Okino T. A case study of human infection with Cysticercus cellulosae (Cestoda: Taeniidae) found in Okinawa Prefecture, Japan. Kawasaki Med J. 1996;22:81–87. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hasegawa H, Bitoh S, Koshino K, Obashi J, Yamamoto H. Intramedullary spinal cysticercosis. A case report. Sekitsui Sekizui (Vertebra and Spinal cord) 1991;4:337–341. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kajiwara N, Muramatsu R, Goto H, Usui M. A case of intraocular cysticercosis. J Eye (Atarashii Ganka) 1993;10:119–122. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yamasaki H, Nakao M, Sako Y, Nakaya K, Sato MO, Mamuti W, Okamoto M, Ito A. DNA differential diagnosis of human taeniid cestodes by base excision sequence scanning thymine-base reader analysis with mitochondrial genes. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:3818–3821. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.10.3818-3821.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamasaki H, Allan JC, Sato MO, Nakao M, Sako Y, Nakaya K, Qiu D, Mamuti W, Craig PS, Ito A. DNA differential diagnosis of taeniasis/cysticercosis by multiplex PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:548–553. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.2.548-553.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yamasaki H, Nakao M, Sako Y, Nakaya K, Sato MO, Ito A. Mitochondrial DNA diagnosis for taeniasis and cysticercosis. Parasitol Int. 2006;55(suppl):S81–S85. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2005.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yanagida T, Yuzawa I, Joshi DD, Sako Y, Nakao M, Nakaya K, Kawano N, Oka H, Fujii K, Ito A. Neurocysticercosis: Assessing where the infection was acquired from. J Travel Med. 2010;17:206–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2010.00409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shimamoto Y, Sugiyama E, Inaba M, Shinoda J, Shimazaki K, Yamada F. Cerebral cysticercosis treated with praziquantel - a case report. No To Shinkei. 1994;46:381–386. (in Japanese) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sugiyama E, Shimamoto Y, Yamada F, Inaba M. A case of cerebral cysticercosis (cysticercosis racemosus) Clin Parasitol. 1992;3:146–148. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yawata Y, Kamata Y, Nagai C, Suzuki K, Shibata Y, Ajitsu S, Sano R, Takenaka K, Kamii H, Watanabe T. Diabetic come without preceeding thirst sensation in a case of cerebral cysticercosis. Yamagata Med J. 1993;11:79–84. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yamasaki H, Araki K, Aoki T. Parasitic diseases examined during the past 16 years in the Department of Parasitology, Juntendo University School of Medicine. Juntendo Med J. 1994;40:262–279. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 54.Takeshita I, Li HZ, Imamoto N, Cao YP, Gou CF, Liu DQ, Piao HZ, Fukui M. Unusual manifestation of cerebral cysticercosis. Fukuoka Med J. 1994;85:29–34. (in Japanese) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Terada K, Seno K, Uetsuhara K, Asakura T. A case of cerebral cysticercosis: Cyst growth is confirmed by CT scan during 6 years of follow-up. No Shinkei Geka. 1990;18:391–395. (in Japanese) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ohnishi K, Murata M, Nakane M, Takemura N, Tsuchida T, Nakamura T. Cerebral cysticercosis. Int Med. 1993;32:569–573. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.32.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Miyake H, Takahashi K, Tsuji M, Nagasawa S, Ohta T, Araki T. A surgical case of solitary cerebral cysticercosis. No Shinkei Geka. 1993;21:561–565. (in Japanese) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Endo K, Hirayama K, Hida C, Tsukamoto T, Yamamoto T. Domestic infection of neurocysticercosis in a Japanese woman, who had not traveled overseas. Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 1995;35:408–413. (in Japanese) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nagayama M, Shinohara Y, Nagakura K, Izumi Y, Takagi S. Distinctive serial magnetic resonance changes in a young woman with rapidly evolved neurocysticercosis, with positron emission tomography results. J Neuroimaging. 1996;6:198–201. doi: 10.1111/jon199663198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Morioka T, Yamamoto T, Nishio S, Takeshita I, Imamoto N, Fukui M. Magnetoencephalographic features in neurocysticercosis. Surg Neurol. 1996;45:176–182. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(96)80013-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shiota T, Yamada M, Uchikawa R, Tegoshi T, Yoshida Y, Arizono N. Epidemiological trend on diphyllobothriasis latum/nihonkaiense and taeniasis saginatus in Kyoto. Clin Parasitol. 2003;14:81–83. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 62.Komura K, Hamada A, Okuzawa E. Parasitosis treated at Yokohama Rosai Hospital 2000-2008. Clin Parasitol. 2008;19:103–105. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Okumura Y, Nakazawa S, Yoshino S, Yamao K, Inui K, Yamachika H, Arakawa A, Furuta T, Kishi K, Doai K, Toda M, Yamagishi S, Wakabayashi T, Suzui N, Watanabe K, Yamachika R, Asakura N, Okushima K, Nagase K. A case of taeniasis saginata detected by intestino-fiberscopical examination. Clin Parasitol. 1990;1:112–114. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 64.Suzuki T, Haruma K, Shimamoto F, Tsuda T, Toyoshima H, Yoshihara M, Sumii K, Kajiyama G, Tsuji M, Sakamoto K, Kawamura M. A case of taeniasis saginata co-infected with clonorchiasis sinensis diagnosed by duodeno-fiberscope. Cho Shikkan no Rinsho. 1990;3:30–34. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ohnishi K, Murata M. Gastrografin treatment for taeniasis saginata. Clin Parasitol. 1990;1:115. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sekiya T, Kimura K, Sakuma M, Mishiku Y, Asakura Y, Kawamura I, Uchida A, Iwata T. A caseof taeniasis saginata. Shonika Rinsho. 1992;45:585–588. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nakao A, Sakagami K, Hirohata T, Hara M, Obayashi N, Mitsuoka S, Uda M. A case of taeniasis saginata. Hiroshima Med J. 1996;49:1369–1370. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tomizawa I, Takizawa Y, Sakamoto Y. A case of Taenia saginata entered our hospital. Sapporo City Hosp J. 1996;56:45–47. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nihashi J, Shibata Y, Kajimura M, Ito G, Hanai H, Kaneko E, Terada M. A case of gastrografin-resistant tapeworm infection. Clin Parasitol. 1996;7:131–134. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ohgami K, Ozasa S, Takahashi K. A case of taeniasis saginata. Teishin Igaku. 1997;49:654–655. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nakayasu S, Kawabata M, Ishihara O, Matsuda Y, Ishii A, Terada M. A case of taeniasis saginata detected by mass-screening of the colon cancer, and treated with gastrografin method and praziquantel. Clin Parasitol. 1998;9:16–18. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shiono Y, Hata K, Aosai F, Norose K, Yano A, Kawashima K, Yamada M. A case of taeniasis saginata diagnosed by spontaneously expulsed segments at labor. Clin Parasitol. 2001;12:43–44. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ishida T, Araki T, Nishiyama T, Hirata I, Katsu K. Clinical study of diphyllobothriasis nihonkaiense and taeniasis saginata in Shinsei Hospital - special reference to treatment. Clin Parasitol. 2001;12:48–53. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yoshimura R, Harada N, Sadamoto Y, Takahashi M, Kubokawa K, Ito K, Tanaka M, Toyoda T, Yamaguchi Y, Ohkumi A, Miyahara M, Nawada S. Two cases of taeniasis saginata. Rinsho to Kenkyu. 2002;79:111–114. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yamamoto K, Kawahara K, Shimidzu N, Tanioka K, Takatoo T, Saida Y. A report of a case with taeniasis saginata. Iwata City Sogo Hosp J. 2002;4:8–11. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nishimura Y, Yamaguchi S, Sahara T, Nakazaki Y, Tsuruta S, Fujimori I, Kino H, Yamasaki H, Nakao M, Ito A, Kuramochi T. Two cases of intestinal cestode infections diagnosed by genetic analysis. Clin Parasitol. 2007;18:46–48. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 77.Miyamoto S, Komatsu N, Asai Y, Kurihara R, Asaoka A, Kawamura H, Arakawa Y, Takahashi K. A case of taeniasis saginata treated using gastrografin. Nippon Univ Med J. 2003;62:229–231. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 78.Oyama N, Shiozaki H, Tahara T, Takada K. A case of taeniasis saginata treated by endoscopy using gastrografin. Progr Digest Endosc. 2007;70:102–103. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 79.Arakaki T, Hasegawa H, Morishima A, Ikema M, Terukina S, Higashionna A, Kinjyo F, Saito A, Asato R, Toma S. Treatment of Taenia solium and T. saginata infections with gastrografin. Jpn J Trop Med Hyg. 1988;16:293–299. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yamasaki H, Morishima Y, Sugiyama H, Muto M. Taenia asiatica infections as an emerging parasitic disease occurring in Kanto district since 2010. IASR. 2011;32:106–107. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nakamura-Uchiyama F, Kobayashi K, Iwabuchi S, Ohnishi K. Four cases of taeniasis asiatica infected by eating raw pig liver or cattle liver. IASR. 2011;32:107–108. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 82.Haruki K, Tamano M, Miyoshi Y, Araki J. A case of Taenia asiatica infection. IASR. 2011;32:108. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kawai S, Kirinoki M, Chigusa Y, Matsuoka H, Suzuki T. Human cases due to Taenia asiatica occurring in Ryomo district of Gumma and Tochigi prefectures. IASR. 2011;32:109–111. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yamasaki H, Muto M, Morishima Y, Sugiyama H, Kawanaka M, Nakamura-Uchiyama F, Ohgame M, Kobayashi K, Ohnishi K, Kawai S, Okuyama T, Saito K, Miyahira Y, Yanai H, Matsuoka H, Haruki K, Miyoshi Y, Akao N, Akiyama J, Araki J. Human cases infected with Taenia asiatica occurring in Kanto district, 2010. Clin Parasitol. 2011;22:75–78. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 85.Okamoto M, Nakao M, Blair D, Anantaphruti MT, Waikagul J, Ito A. Evidence of hybridization between Taenia saginata and Taenia asiatica. Parasitol Int. 2010;59:70–74. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Miyagami M, Satoh K. Diagnosis and treatment for an aged neurocysticercosis patient. Roka to Shikkan. 1991;4:436–441. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 87.Uyama E, Cho I, Araki T, Osuga K. A case of neurocysticercosis diagnosed with severe headache during staying in Honduras. Zutu Kenkyu Kaishi. 1991;18:64–66. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 88.Miyashita T, Miyaji A, Nishitani H, Mano K, Kunii O, Miyashita H, Shibuya T, Chen TH. A case of neurocysticercosis with cystic lesions in the lung. Clin Parasitol. 1992;3:140–142. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kakizaki T, Kawai S, Takemura K, Tanaka M, Monobe T, Kim E, Nagareda T, Kotoh R, Nishiyama T, Araki T. An operated case of neurocysticercosis. Clin Parasitol. 1992;3:143–145. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kadotani H, Takatsuka K, Tanaka H, Yoshikawa N, Komatsu T. Cysticercosis. A case report with special reference to CT and MRI findings. Neuol Med (Tokyo) 1992;36:399–402. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kimura M, Sakatani K, Maekura S, Satou T, Furukawa T, Miyazato T, Hashimoto S. A case of cerebral cysticercosis cellulosae hominis. Acta Med Kinki Univ. 1993;18:155–161. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Higashi K, Yamagami T, Satoh G, Shinnou M, Tanaka T, Handa H, Furuta M. Cerebral cysticercosis: a case report. Surg Neurol. 1993;39:474–478. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(93)90034-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Oka Y, Fukui K, Shoda D, Abe T, Kumon Y, Sakai S, Torii M. Cerebral cysticercosis manifestating as hydrocephalus - case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 1996;36:654–658. doi: 10.2176/nmc.36.654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yamasaki H, Nakaya K, Nakao M, Sako Y, Ito A. Significance of molecular diagnosis using histopathological specimens in cestode zoonoses. Trop Med Health. 2007;35:307–321. [Google Scholar]