Abstract

Cell-cell signalling of semaphorin ligands through interaction with plexin receptors is important for the homeostasis and morphogenesis of many tissues and is widely studied for its role in neural connectivity, cancer, cell migration and immune responses1. SEMA4D and Sema6A exemplify two diverse vertebrate, membrane-spanning semaphorin classes (4 and 6) that are capable of direct signalling through members of the two largest plexin classes, B and A, respectively2,3. In the absence of any structural information on the plexin ectodomain or its interaction with semaphorins the extracellular specificity and mechanism controlling plexin signalling has remained unresolved. Here we present crystal structures of cognate complexes of the semaphorin-binding regions of plexins B1 and A2 with semaphorin ectodomains (human PLXNB11–2–SEMA4Decto and murine PlxnA21–4–Sema6Aecto), plus unliganded structures of PlxnA21–4 and Sema6Aecto. These structures, together with biophysical and cellular assays of wild-type and mutant proteins, reveal that semaphorin dimers independently bind two plexin molecules and that signalling is critically dependent on the avidity of the resulting bivalent 2:2 complex (monomeric semaphorin binds plexin but fails to trigger signalling). In combination, our data favour a cell-cell signalling mechanism involving semaphorin-stabilized plexin dimerization, possibly followed by clustering, which is consistent with previous functional data. Furthermore, the shared generic architecture of the complexes, formed through conserved contacts of the amino-terminal seven-bladed β-propeller (sema) domains of both semaphorin and plexin, suggests that a common mode of interaction triggers all semaphorin–plexin based signalling, while distinct insertions within or between blades of the sema domains determine binding specificity.

Semaphorins are sub-divided into eight classes of cell-attached or secreted glycoproteins4, characterized by an extracellular N-terminal sema domain followed by a cysteine rich PSI (plexin, semaphorin, integrin) domain, which form homodimers through substantial sema–sema domain interfaces5,6. Plexins are large type 1 single transmembrane-spanning cell surface receptors (Fig. 1a) and are divided into four classes2,7. Sequence analyses indicate an N-terminal sema domain, followed by a combination of three PSI domains and six IPT domains (Ig domain shared by plexins and transcription factors). For class B plexins the prototypic interaction of SEMA4D with PLXNB1 is implicated in migration and proliferation of neuronal, endothelial and tumour cells as well as in angiogenesis and axonal guidance8,9. Class 6 semaphorins (Sema6A, B, C and D) typically interact with class A plexins; Sema6A–PlxnA2 signalling controls axon guidance in the hippocampus and granule cell migration in the cerebellum3,10,11. A and B plexins have essentially identical cytoplasmic structures comprising a Ras GTPase-activating protein (GAP) topology with an inserted Rho GTPase-binding domain (RBD)12,13. Various mechanisms have been proposed for semaphorin-mediated activation of the plexin cytoplasmic region6,14–17 but molecular level analyses of the effect of semaphorin-binding on plexin structure and oligomeric state are necessary to provide the paradigm for semaphorin–plexin signalling.

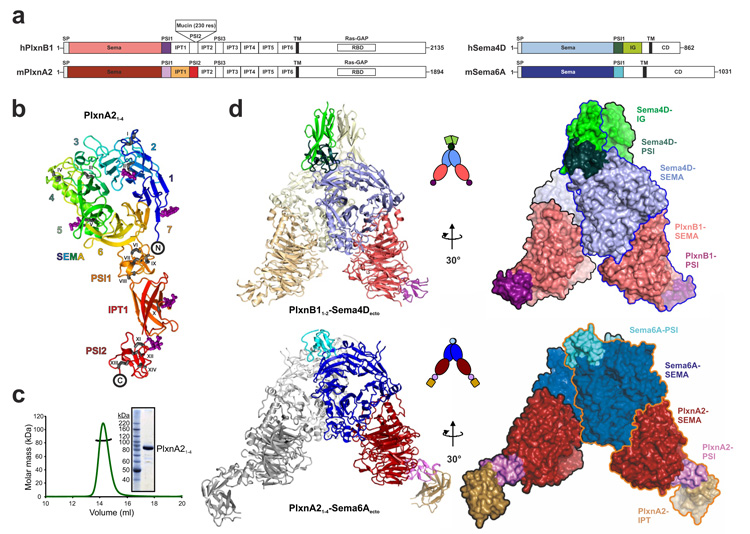

Figure 1. The semaphorin–plexin complexes share a common architecture.

a, Schematic domain organization of human PLXNB1, mouse PlxnA2, human SEMA4D and mouse Sema6A. PLXNB1 contains an additional mucin-like domain inserted into the PSI2 domain. SP, signal peptide; TM, transmembrane. The domains included in the crystallization constructs are coloured. b, Ribbon representation of PlxnA21–4 ‘rainbow’ colour ramped from blue (N terminus) to red (C terminus) with the β-propeller blades numbered. N-linked glycans are shown in magenta ball-and-stick representation and the 14 disulphide bridges (black stick presentation) are marked with Roman numbering. c, Multi-angle light scattering indicates an experimental molecular mass (black line) of 83.7 ± 0.8 kDa for PlxnA21–4 (green line; elution profile, axis not shown) as observed by SDS–PAGE (inset) and in agreement with the theoretical molecular mass for a monomer (85 kDa). d, Ribbon representation (left panel), cartoon drawing (middle panel) and surface representations with individual protein chains indicated by an outline (right panel) of the PLXNB11–2–SEMA4Decto and PlxnA21–4–Sema6Aecto complexes. Domains are coloured as in Fig. 1a.

We have determined crystal structures of the phylogenetically distant18 PLXNB11–2–SEMA4Decto and PlxnA21–4–Sema6Aecto complexes and the unliganded states of PlxnA21–4 and Sema6Aecto at 3.0, 2.2, 2.3 and 2.3 Å resolution, respectively (see methods and Fig. 1). The PlxnA21–4 sema domain forms a seven-bladed β-propeller, elaborated with distinctive insertions more closely related to the Met receptor19,20 than to the semaphorins5,6 (see Supplementary Fig. 1), which is followed by a PSI domain (PSI-1), an IPT domain (IPT-1) and a second PSI domain (PSI-2) (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 2) that together form a stalk pointing away from the sema domain. The crystal packing provides no evidence for oligomerization and PlxnA21–4 is monomeric in solution to concentrations of at least 29 μM (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 3). Unbound SEMA4Decto5 and Sema6Aecto form dimers in the crystal and in solution (Supplementary Figs 3 and 4). The PlxnA21–4–Sema6Aecto and PLXNB11–2–SEMA4Decto complexes are structurally similar. In both, the semaphorins and plexins interact in a ‘head-to-head’ fashion through their sema domains such that the semaphorin dimer brings together two plexin monomers to form a symmetric 2:2 complex (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Figs 2 and 4). Each of the plexins almost exclusively interacts one-to-one with a separate semaphorin chain and the two plexins diverge from the semaphorin dimer without interacting with each other. This architecture positions semaphorin and plexin C termini in a trans (anti-parallel) arrangement suitable for signalling between apposing cell surfaces.

Neither the semaphorin ectodomains of SEMA4Decto and Sema6Aecto nor the four domain N-terminal portion of PlxnA21–4 undergo large conformational changes upon complex formation (Supplementary Fig. 5). Superpositions of the bound and unbound sema domains of SEMA4Decto, Sema6Aecto and PlxnA21–4 reveal no significant structural differences (Cα atom root mean squared deviations (r.m.s.d.) of 0.85, 0.71 and 0.59 Å, respectively). Conformational changes at the semaphorin–plexin interfaces are very limited (Supplementary Fig. 5a), indicating that the binding surfaces are essentially preformed in solution. Small differences in the orientation of the two subunits of the semaphorin dimer are apparent on comparison of the unbound and bound crystal structures for both SEMA4Decto and Sema6Aecto; however, there is no evidence for a re-orientation characteristic of complex formation and the dimer interface remains predominantly unchanged (Supplementary Fig. 5b). A similar low level of orientational flexibility is observed in the linkage of the sema domains with semaphorin PSI and PlxnA21–4 PSI-1 domains (Supplementary Fig. 5b, c), as well as between the plexin IPT and PSI domains (Supplementary Fig. 5c); however, PlxnA21–4 PSI-2 is disordered in the complex crystal. Thus the semaphorin ectodomains appear to be relatively rigid structures, but full-length plexins may be more flexible.

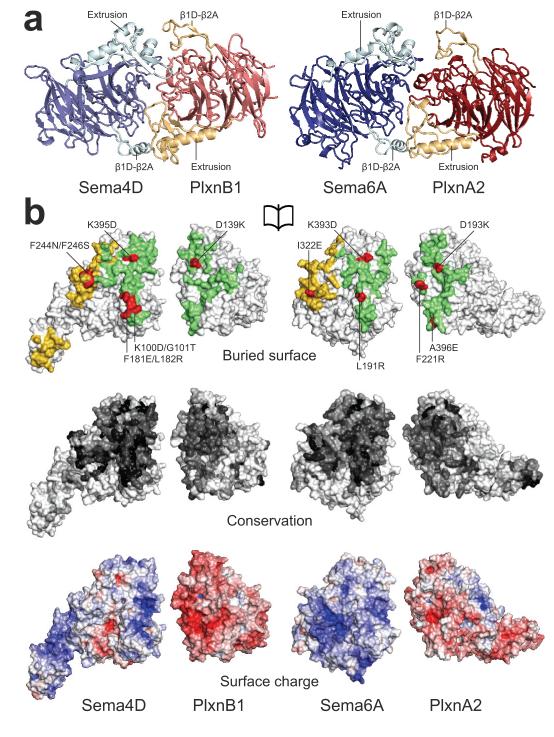

The representative semaphorin 4–plexin B and semaphorin 6–plexin A complexes have the same overall shape, each of the four protein chains is located in a comparable position and orientation and the interface is located at equivalent positions on the sema domains (Figs 1d and 2), although the plexin adopts a slightly different orientation in the two complexes (Supplementary Fig. 6a). The sema domains are highly conserved within the semaphorin and plexin families both in structure (PLXNB11–2 and PlxnA21–4 r.m.s.d. of 1.64 Å for 390 equivalent Cα atoms; SEMA4Decto and Sema6Aecto r.m.s.d. of 1.73 Å r.m.s.d. for 427 Cα pairs; see also Supplementary Figs 1 and 6b) and in overall charge distribution (semaphorins positive and plexins negative; Fig. 2b). Furthermore, sequence alignments across the respective families show conserved surface residues cluster at the complex interface consistent with this mode of binding being common to all semaphorin–plexin interactions (Fig. 2b).

Figure 2. Similar characteristics mediate the semaphorin–plexin interactions.

a, Ribbon representation of the pseudo twofold arrangement of the interacting semaphorin and plexin sema domains. b, An opened view showing the semaphorin–plexin interface (green), the semaphorin homodimer interface (yellow) and interface mutants used in biophysical and cellular assays (red) (top panel). Semaphorin and plexin are colour-coded according to residue conservation (from non-conserved, white, to conserved, black) based on alignments containing sequences from all vertebrate semaphorin and plexin classes (middle panel). Semaphorin and plexin coloured by electrostatic potential from red (−8 kbT/ec) to blue (8 kbT/ec) (bottom panel). In both complexes the interface consists of conserved complementary charged patches.

A single semaphorin and plexin chain together form an extensive, slightly discontinuous interface, burying 2,500 and 2,060 Å2 in the PLXNB11–2–SEMA4Decto and PlxnA21–4–Sema6Aecto complexes, respectively, and comprising a mixture of hydrophobic and hydrophilic (complementarily charged) patches (Fig. 2). Previous functional studies have implicated the semaphorin and plexin sema domains in complex formation and signalling2,21. The complex structures reveal that the same ‘edge on’ face of the β-propeller is used for the interaction by both families of molecules (Fig. 2a). This interaction site is predominantly formed by distinctive insertions in or between blades 1 to 5 of the semaphorin and plexin sema domains, with very few residues contributing directly from the blades of the standard β-propeller architecture (Supplementary Figs 2 and 4). The two most prominent insertions, a ~20 residue loop between blades 1 and 2 (β1D-β2A) and a ~70 residue insert within blade 5 (first termed the extrusion in semaphorins5), are both present in semaphorins and plexins but with different lengths and conformations (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Figs 2 and 4). These novel structural features interact in an anti-parallel (trans) fashion (the semaphorin blade 1-2 loop with the plexin blade 5 insertion and vice versa) leading to a twofold arrangement of the interacting sema domains. Finer-grained differences in the interface-forming insertions (Supplementary Fig. 6c), particularly between the plexins PLXNB11–2 and PlxnA21–4, seem sufficient to discriminate against non-cognate complex formation.

The architecture of the complex, with a semaphorin dimer binding two plexin molecules indicates that bivalency is likely to have an important role in semaphorin–plexin interactions. Indeed a strong bivalency effect is observed in surface plasmon resonance (SPR) equilibrium experiments for both the PLXNB11–2–SEMA4Decto and PlxnA21–4–Sema6Aecto interaction (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 7). Consistent with bivalency, when plexin is coupled to the Biacore chip, the semaphorin–plexin interaction does not follow simple 1:1 binding and the apparent affinity increases at higher plexin coupling densities due to the greater potential for bivalent interaction (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 7a, c)22. To facilitate direct comparison with previously reported assays of semaphorin–plexin binding affinities the SPR experiments were repeated with Fc-tagged dimerized Sema6Aecto (Supplementary Fig. 7g) and, although it is difficult to reach an exclusively bivalent interaction in SPR experiments22, apparent affinities of up to 15 nM were measured, close to the nM values observed for cell-based assays with Fc-tagged semaphorins2,3. As expected, the reversed interaction (soluble plexin binding to chip coupled semaphorin; only performed for PlxnA21–4–Sema6Aecto) is monovalent (1:1 binding), with a greater than 40-fold decrease in binding affinity (Kd = 2.3 μM), and independent of the density of semaphorin on the chip (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 7d). In order to dissect further the role of dimeric semaphorin in the bivalent interaction the homodimer interface was disrupted by mutagenesis to produce monomerized semaphorin (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 8). The bivalent interaction observed for plexin-coupled chips is converted to a monovalent interaction; the monomerized semaphorins giving Kd values of 5.5 μM for SEMA4Decto(F244N/F246S) and 1.3 μM for Sema6Aecto(I322E) (Supplementary Fig. 7b, e) which is similar to the reversed 1:1 interaction observed for both dimeric and monomerized semaphorin-coupled chips (Supplementary Fig. 7d, f). Earlier studies have shown that semaphorin dimers are necessary for activity21,23,24, possibly due to avidity. However, the monomerized SEMA4Decto(F244N/F246S) is not capable of triggering the collapse response in the well established COS cell-based assay25 even at a concentration ninefold above its Kd for PLXNB1 (Fig. 3c, d), showing that 1:1 binding of semaphorin to plexin is not enough to trigger signalling. Thus, semaphorin dimers facilitate bivalent interaction, necessary for sufficiently tight binding to plexins and crucial for semaphorin–plexin-induced cell-cell signalling.

Figure 3. Bivalent interaction is critical for semaphorin–plexin-induced cell-cell signalling.

a, SPR equilibrium experiments of PLXNB11–2–SEMA4Decto (top panels; wild-type SEMA4Decto and monomerized SEMA4Decto(F244N/F246S)) and PlxnA21–4–Sema6Aecto (bottom panels; Sema6Aecto over PlxnA21–4 and reversed orientation, see also Supplementary Fig. 7). RU, response units. b, MALS analyses indicate molecular masses (black lines) of 174 ± 2 kDa and 92 ± 1 kDa for SEMA4Decto and SEMA4Decto(F244N/F246S), respectively (elution profiles; green and blue lines, axis not shown). c, d, Cos-7 cell collapse assay showing representative images of non-collapsed cells (c, left panel) and SEMA4Decto-induced collapsed cells (c, right panel). Scale bar, 40 μm. e, EGL explants (green) grown on NIH3T3 cells (red) without (left panel) or with (right panel) Sema6A expression show the migration of post-mitotic granular neurons. WT, wild type. Scale bar, 200 μm. f, Quantification of migrating post-mitotic neurons from cultured EGL explants of either PlxnA2+/− or PlxnA2−/− mice grown on wild type (shaded) or Sema6A expressing cells (hatched). (**P ≤ 0.005 by unpaired t-test). g, Model for semaphorin-stabilized plexin signalling. Binding of semaphorin stabilizes plexin dimerization, sufficient plexin ectodomain flexibility may enable plexin-to-plexin cis interaction in their membrane-proximal regions (upper panel) and seed further oligomerization. Possibly, dimerization is preceded by a ‘switch-blade’ conformational change in the plexin ectodomain (lower panel) exposing cis interaction sites leading to extracellular clustering. Two types of initial binding events (dotted enclosures) could result in the dimer and cluster architecture of either the upper or lower panel. The precise arrangement of the cytoplasmic region in the active state triggered by extracellular clustering cannot be specified.

Analyses of several semaphorin–plexin interface mutants (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Figs 2 and 4) in SPR and cell collapse assays are consistent with the crystallographically determined complex structures (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 9). Sema6Aecto mutant L191R binds PlxnA21–4 5.5-fold weaker (Supplementary Fig. 9h). SEMA4Decto mutants K100D/G101T and F181E/L182R and PlxnA21–4 mutants F221R and A396E all completely abolish binding (Supplementary Fig. 9f, g), and the SEMA4Decto mutants do not collapse COS-7 cells (Fig. 3d). A PlxnA2(A396E) mutant, expressed in COS-7 cells, has also been reported to no longer bind Sema6A11. We further corroborated the interface by charge-reversal at a conserved salt bridge in both complexes; PLXNB11–2(D139K)–SEMA4Decto(K395D) (Supplementary Fig. 9c-e) and PlxnA21–4(D193K)–Sema6Aecto(K393D) (Supplementary Fig. 9i–k). The semaphorin and plexin charge mutants bind over 200-fold and 9-fold weaker to their wild-type counterparts respectively, whereas binding is restored when the charge mutants are combined. Cerebellar granule cell migration assays on 3T3 cells directly demonstrate that contact with cells expressing full-length Sema6A reduces neuronal migration and that PlxnA2 is required for these neurons to respond to Sema6A, as previously suggested from genetic data (Fig. 3e, f)3,11. Mice harbouring the PlxnA2 A396E mutation have previously been shown to exhibit defects in granule cell migration which are similar to PlxnA2−/− null mutant and Sema6A−/− mice11, providing evidence in vivo for the importance of the Sema6A–PlxnA2 interaction defined by our structural data. The extensive class 3 semaphorin–plexin A interactions are distinctive in requiring members of the neuropilin family as co-receptors15. Previous studies have implicated two regions of the Sema3A sequence in function, sema domain blade 3 (ref. 21) and a K108N mutant that abolishes signalling in vivo (but does not disrupt neuropilin-1 binding)26. Both features map to the semaphorin–plexin interface that we observe consistent with direct Sema3–PlxnA interactions. Overall, the effects of semaphorin–plexin interface mutants in vitro and in vivo support the structural data and show that this interface is likely common to all semaphorin–plexin interactions.

In combination our above studies indicate that dimerization of the N-terminal domains of the plexin extracellular segment, resulting from bivalent semaphorin binding, is prerequisite for plexin signalling. After submission of this study, a similar architecture, and consequent role for plexin dimerization in signalling, was reported based on crystal structures of complexes of Sema7A and of a viral mimic with a sema-PSI fragment of PlxnC1 (ref. 27). We have, in addition, carried out biophysical analyses of eight domain and full-length extracellular (ten domain) constructs for PlxnA2 (PlxnA21–8 and PlxnA21–10) and of the entire cytoplasmic region of plexin B1 (PLXNB1cyto) (Supplementary Fig. 10). Both PlxnA21–8 and PlxnA21–10 show increasing evidence of intermolecular interactions at higher concentrations consistent with the plexin ectodomain having some propensity for weak cis-interactions through membrane proximal domains 5–10 before semaphorin binding. In isolation, PLXNB1cyto remains monomeric at concentrations of at least 360 μM (Supplementary Fig. 10c) as shown previously at lower concentrations13. It has been reported that plexin activation can be induced by concurrent binding of intracellular Rnd1 and cluster-inducing antibodies16,28 and that semaphorin binding induces clustering of plexins15,16, possibly preceded by a conformational change in the plexin14. Full-length transmembrane PLXNB1 has weak cis-interaction which is further enhanced by SEMA4D16. Furthermore covalently oligomerized extracellular segment-deleted PLXNB1 is active independently of SEMA4D16. Semaphorin-stabilized plexin dimerization may seed further oligomerization through plexin-to-plexin cis interactions involving the membrane-proximal IPT domains or through intracellular regions16,28 (Fig. 3g). We observe some inter-domain flexion for the PlxnA21–4 IPT-1 and PSI-2 domains (Supplementary Fig. 5c) and additional flexibility may exist in the complete plexin extracellular region, analogous to that observed for the homologous Met receptor19,20,29, to enable plexins to undergo a conformational change14. This change could expose cis interaction sites for extracellular clustering, providing an extra level of regulation to tightly control the activity of semaphorin–plexin induced cell-cell signalling.

METHODS

Production of SEMA4Decto, PLXNB11–2, Sema6Aecto, PlxnA21–4, PlxnA21–8, PlxnA21–10 and PLXNB1cyto

Human PLXNB11–2, human SEMA4Decto, mouse PlxnA21–4, PlxnA21–8, PlxnA21–10 and mouse Sema6Aecto (residues 20–535, 22–677, 35–703, 35–1040, 35–1231 and 19–571, respectively) were cloned into the pHLsec vector30 in-frame with a C-terminal His-tag. For crystallization experiments SEMA4Decto was produced in CHO lecR cells as described previously5, PLXNB11–2 was expressed in HEK-293T cells30 in the presence of kifunensine31 and Sema6Aecto and PlxnA21–4 were expressed in HEK-293S GnTI− cells32. For all other experiments proteins were expressed in HEK-293T cells (without glycosylation inhibitors) with the exception of Sema6Aecto and PlxnA21–4 that were expressed in HEK-293S cells for MALS and AUC experiments. Proteins were purified from buffer-exchanged medium by immobilized metal-affinity and size-exclusion chromatography. SEMA4Decto, Sema6Aecto and PlxnA21–4 were purified individually, whereas after metal-affinity purification PLXNB11–2 was mixed with purified SEMA4Decto in a 2:1 ratio and the complex was subsequently purified by size-exclusion chromatography. The full-length intracellular domain of human PLXNB1 (residues 1511–2135; PLXNB1cyto) was cloned into the pBac PAK9 vector (Clontech) in-frame with an N-terminal His-tag and used for transfection of 2 ml Sf9 cells (1 × 106 cells ml−1). After five days the supernatant was collected and three rounds of virus amplification, each with a 1:100 dilution were carried out. For protein expression Sf9 cells with a density of 1.4 × 106 cells ml−1 were inoculated with the virus from the third round of amplification (1:10). After 3 days the cells were collected by centrifugation and resuspended in lysis buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors. Cells were lysed by sonication. PLXNB1cyto was purified from cleared lysate by immobilized metal-affinity and size-exclusion chromatography.

Crystallization and data collection

The PLXNB11–2–SEMA4Decto complex was concentrated to 8.0 mg ml−1 in 10 mM Tris, pH 8.0 and 150 mM NaCl. Sema6Aecto and PlxnA21–4 were concentrated to 13.1 mg ml−1 and 6.8 mg ml−1, respectively, both in 10 mM Hepes, pH 7.5 and 75 mM NaCl. Because we were unable to obtain well diffracting crystals of the glycosylated PlxnA21–4–Sema6Aecto complex both Sema6Aecto and PlxnA21–4 were deglycosylated with endoglycosidase F1 (ref. 31) and mixed at a molar ratio of 1:1 to a final concentration of 7.3 mg ml−1 before crystallization. For crystallization of individual proteins Sema6Aecto and PlxnA21–4 were not deglycosylated. Sitting drop vapour diffusion crystallization trials were set up using a Cartesian Technologies pipetting robot and consisted of 100 nl protein solution and 100 nl reservoir solution33. Crystallization plates were placed in a TAP Homebase storage vault maintained at 18 °C and imaged via a Veeco visualization system34. The PLXNB11–2–SEMA4Decto complex crystallized in 0.1 M Tris, pH 7.0, 0.2 M calcium acetate, 6% v/v glycerol, 20% w/v PEG3000, the Sema6Aecto–PlxnA21–4 complex in 0.12 M Mes, pH 6.0, 1% v/v ethyl acetate, 12.4% v/v 2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol, Sema6Aecto in 0.2 M di-ammonium hydrogen citrate, 6% w/v d-galactose, 20% w/v PEG3350, and PlxnA21–4 in 0.06 M HEPES, pH 7.0, 0.13 M magnesium chloride and 12.8% w/v PEG6000. Before diffraction data collection crystals were soaked in mother liquor supplemented with glycerol (25%, 15%, 20% and 20% v/v glycerol for PLXNB11–2–SEMA4Decto, PlxnA21–4–Sema6Aecto, Sema6Aecto and PlxnA21–4, respectively) and subsequently flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen or in a cryo nitrogen gas stream. Data were collected at 100 K at Diamond beamline I03 (PLXNB11–2–SEMA4Decto, PlxnA21–4–Sema6Aecto and Sema6Aecto) and at European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) beamline ID23-1 (PlxnA21–4). Diffraction data were integrated and scaled with the HKL suite35 (PLXNB11–2–SEMA4Decto) or with MOSFLM36 and SCALA37 in CCP438 (PlxnA21–4–Sema6Aecto, Sema6Aecto and PlxnA21–4) (see Supplementary Table 1).

Structure determination and refinement

First we solved the structure of Sema6Aecto by molecular replacement in PHASER39 using the structure of Sema3A6 (Protein DataBase (PDB) code 1Q47) as a search model. This solution was subjected to one round of simulated annealing refinement in PHENIX40 and subsequently re-built automatically by ARP/wARP41 and completed by manual rebuilding in COOT42 and refinement in PHENIX. The structure of the PlxnA21–4–Sema6Aecto complex was solved by molecular replacement in PHASER with the Sema6Aecto structure and the Met-receptor structure20 (PDB code 2UZX) as search models, successively. This partial model was re-built automatically by ARP/wARP and BUCCANEER43 and completed by several cycles of manual rebuilding in COOT and refinement in PHENIX. PlxnA2 domain PSI2 was omitted from the model due to disorder. Before manual rebuilding a mask was constructed around the putative PlxnA21–4 molecule in the PlxnA21–4–Sema6Aecto complex in CCP4, and the electron density inside the mask was used for molecular replacement in PHASER to solve the PlxnA21–4 structure. Using this solution an initial model was build automatically by ARP/wARP and completed by manual rebuilding in COOT and refinement in PHENIX. The structure of the PLXNB11–2–SEMA4Decto complex was solved by molecular replacement in PHASER with the SEMA4Decto structure5 (PDB code 1OLZ) and the PlxnA21–4 structure as search models, successively. This solution was re-built automatically by BUCCANEER and completed by several cycles of manual rebuilding in COOT and refinement in PHENIX and BUSTER44. Refinement statistics are given in Supplementary Table 1. All models were validated with MOLPROBITY45. Ramachandran statistics are as follows (favoured/disallowed (%)): PLXNB11–2–SEMA4Decto 94.5/0.8, PlxnA21–4–Sema6Aecto 96.6/0.3, Sema6Aecto 96.3/0.1, PlxnA21–4 98.0/0.3. Superpositions were calculated using SHP46, electrostatics potentials were generated using APBS47, alignments were calculated using ClustalW48 and buried surface areas of protein–protein interactions were calculated using PISA49. Figures were produced using PyMOL (http://www.pymol.org/), ESPRIPT50, ConSurf51 and Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems) and Corel Draw (Corel Corporation).

Site-directed mutagenesis

Semaphorin–semaphorin dimer interface mutants SEMA4Decto(F244N/F246S) (introducing a glycosylation site) and Sema6Aecto(I322E) and semaphorin–plexin interface mutants PLXNB11–2(D139K), PlxnA21–4(D193K), PlxnA21–4(F221R), PlxnA21–4(A396E), SEMA4Decto(K100D/G101T), SEMA4Decto(F181E/L182R), SEMA4Decto(K395D), Sema6Aecto(L191R) and Sema6Aecto(K393D) (see Fig. 2) were generated by a two-step overlapping PCR and cloned into the pHLsec mammalian expression vector, resulting in protein constructs with a C-terminal His6 tag30, a C-terminal BirA recognition sequence for biotinylation52 or a C-terminal Fc tag for covalent dimerization. All mutant proteins were expressed in HEK-293T cells to ensure full glycosylation and were secreted at similar levels to the wild-type proteins. The stringent quality control mechanisms specific to the mammalian cell secretory pathway ensure that secreted proteins are correctly folded53. Mutant proteins were used for SPR, cell collapse, AUC and MALS experiments.

Multi-angle light scattering

MALS experiments were performed during size exclusion chromatography on either an analytical Superdex S200 10/30 column (GE Heathcare) or a TSK-Gel G3000SWXL column (Tosoh) with online static light-scattering (DAWN HELEOS II, Wyatt Technology), differential refractive index (Optilab rEX, Wyatt Technology) and Agilent 1200 UV (Agilent Techologies) detectors. Proteins had previously been purified by size-exclusion chromatography. Data were analysed using the ASTRA software package (Wyatt Technology).

Analytical ultracentrifugation

Sedimentation velocity experiments were performed using an Optima Xl-I analytical ultracentrifuge (Beckman). Purified SEMA4Decto, Sema6Aecto and PlxnA21–4 samples at different concentrations in 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.5 and 150 mM NaCl were centrifuged in double sector 12-mm centerpieces in a An-60 Ti rotor (Beckman) at 50,000 r.p.m. and 20 °C. Protein sedimentation was monitored by Rayleigh interference. Data were analysed using SEDFIT54.

Surface plasmon resonance equilibrium binding studies

SPR equilibrium experiments were performed using a Biacore T100 machine (GE Healthcare) at 25 °C in 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.005% (v/v) polysorbate 20. All proteins were homogeneous with full biological activity and underwent gel filtration in running buffer immediately before use. To mimic the native membrane insertion topology proteins were enzymatically biotinylated at an engineered C-terminal tag and attached via the biotin label to streptavidin that was covalently coupled to the surface52. To investigate the bivalent effect of semaphorin dimer binding to plexin three different concentrations of plexin were coupled to the surface22. The signal from experimental flow cells was corrected by subtraction of a blank and reference signal from a mock coupled flow cell in Scrubber2 (BioLogic). In all experiments analysed, the experimental trace returned to baseline after a regeneration step with 2 M MgCl2 (Supplementary Figs 7 and 9). Kd and maximum analyte binding (Bmax) values were obtained by nonlinear curve fitting of a 1:1 Langmuir interaction model (bound = Bmax/(Kd + C), where C is analyte concentration calculated as monomer) in SigmaPlot (Systat). In experiments with plexin coupled to the surface and dimeric semaphorins injected, binding did not fit well to a 1:1 model due to mixed bivalent and monovalent interaction. Apparent Kd values calculated in these experiments are therefore approximations. Nevertheless, apparent affinities of wild-type and mutant proteins determined at equal plexin coupling concentrations can be compared relative to each other.

Functional cell collapse assay

Cellular collapse assays were performed essentially as described25. Briefly, COS-7 cells were seeded on glass coverslips and transfected with human Plexin B1 carrying an N-terminal Flag-tag. Two days after transfection, cells were treated with medium containing secreted wild-type or mutant SEMA4Decto and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. Finally, the cells were fixed and stained with anti-Flag primary antibody (Sigma) and Alexa 488-labelled secondary antibody (Invitrogen). Cell nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (Invitrogen) and cells were visualized with a TE2000U fluorescence microscope (Nikon) equipped with an Orca CCD camera (Hamamatsu). Plexin B1-expressing cells were classified as collapsed or non-collapsed on the basis of reduced surface area. Each experiment was repeated twice and 2 × 200 cells were counted each time. Results are shown as mean with error bars representing standard error of the mean.

Creation of NIH3T3 stably transfected cell lines

NIH3T3 cells were transfected with pEF-1-dTomato alone or together with pCAGGS-flag-Semaphorin6A-full length. After three rounds of selection, the chosen clones for each line were selected based on two criteria: (1) the co-expression of both genes, (2) the proper targeting of Semaphorin6A to the plasma membrane. Both criteria were tested by fluorescent techniques using monoclonal antibody against the flag tag (clone M2, Sigma).

Explant cultures

C57/BL6 mice at postnatal day 5 (P5) were used from wild-type and Plexin-A2 knock-out (PA2 KO) mice models. Animals were sacrificed according to the Irish Department of Agriculture and European Ethical and Animal Welfare regulations. Cerebella were dissected out and sliced to get 200 μm cerebellum cortex slices. The external granular layer (EGL) was isolated from the cerebellar cortex and cut into 200–500 μm tissue pieces. EGL explants were cultured onto NIH3T3 monolayer cell lines stably transfected with different genes (dTomato, Flag–Semaphorin6A/dTomato). Co-cultures were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with l-glutamine, d-glucose, fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 3 M KCl, for 4 days in 5% CO2, 95% humidity incubator at 37 °C.

Immunohistochemistry

Co-cultures were fixed in 4% PFA for 1 h. After several rinses with PBS, cultures were incubated with the monoclonal antibody against NeuN transcription factor (1:200, clone A60, Millipore) to mark the cell bodies of the post-mitotic cerebellar neurons. Secondary antibody conjugated to Alexa488 was used for further analysis in fluorescent microscopes.

Analysis and quantification

Immunostained co-cultures were examined on a Zeiss LSM-700 microscope. All the migrating post-mitotic cell bodies were counted as well as the explant area measured from each single co-culture picture using ImageJ image analysis software. Migration data were normalized as number of migrating cells for 100 μm2 of explant area, and expressed as mean ± s.e.m. For each experimental condition 50–100 explants were used. Student’s t-test was chosen for further statistical analysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff of European Synchrotron Radiation Facility beamline ID 23-1 and Diamond beamline I03 for assistance with data collection, the Molecular Cytogenetics and Microscopy Core facility of the Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics, T. S. Walter for help with crystallization, G. Sutton for help with MALS experiments, A.F. Sonnen for help with AUC experiments, W. Lu for help with tissue culture, J. M. Grimes for assistance with figures and A. R. Aricescu and D. I. Stuart for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was funded by Cancer Research UK and the UK Medical Research Council. B.J.C.J. is funded by the Human Frontier Science Program, K.J.M. by a Science Foundation Ireland grant, C.H.B. and C.S. by the Wellcome Trust and E.Y.J. by Cancer Research UK.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Author Contributions All authors contributed to the design of the project, data analysis and preparation of the manuscript. R.A.R. cloned, purified and performed SPR and MALS experiments on SEMA4D and PLXNB1 and crystallized and solved its complex structure. C.S. helped with the PLNXB1–SEMA4D complex structure solution. B.J.C.J, cloned, purified and performed SPR, AUC and MALS experiments on Sema6A and PlxnA2 and crystallized and solved the individual and complex structures. C.H.B. did the collapse assays, purified and performed AUC experiments on PLXNB1cyto and helped with other AUC experiments. F.P.-B. performed the granule cell migration assays.

Author Information Coordinates and structure factors for PLXNB11–2–SEMA4Decto, PlxnA21–4–Sema6Aecto, Sema6Aecto and PlxnA21–4 have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with succession numbers 3OL2, 3OKY, 3OKW and 3OKT, respectively. Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints. The authors declare no competing financial interests. Readers are welcome to comment on the online version of this article at www.nature.com/nature.

References

- 1.Kruger RP, Aurandt J, Guan KL. Semaphorins command cells to move. Nature Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;6:789–800. doi: 10.1038/nrm1740. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tamagnone L, et al. Plexins are a large family of receptors for transmembrane, secreted, and GPI-anchored semaphorins in vertebrates. Cell. 1999;99:71–80. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80063-x. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suto F, et al. Interactions between plexin-A2, plexin-A4, and semaphorin 6A control lamina-restricted projection of hippocampal mossy fibers. Neuron. 2007;53:535–547. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.01.028. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kolodkin AL, Matthes DJ, Goodman CS. The semaphorin genes encode a family of transmembrane and secreted growth cone guidance molecules. Cell. 1993;75:1389–1399. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90625-z. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Love CA, et al. The ligand-binding face of the semaphorins revealed by the high-resolution crystal structure of SEMA4D. Nature Struct. Biol. 2003;10:843–848. doi: 10.1038/nsb977. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antipenko A, et al. Structure of the semaphorin-3A receptor binding module. Neuron. 2003;39:589–598. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00502-6. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Winberg ML, et al. Plexin A is a neuronal semaphorin receptor that controls axon guidance. Cell. 1998;95:903–916. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81715-8. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Capparuccia L, Tamagnone L. Semaphorin signaling in cancer cells and in cells of the tumor microenvironment–two sides of a coin. J. Cell Sci. 2009;122:1723–1736. doi: 10.1242/jcs.030197. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Korostylev A, et al. A functional role for semaphorin 4D/plexin B1 interactions in epithelial branching morphogenesis during organogenesis. Development. 2008;135:3333–3343. doi: 10.1242/dev.019760. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kerjan G, et al. The transmembrane semaphorin Sema6A controls cerebellar granule cell migration. Nature Neurosci. 2005;8:1516–1524. doi: 10.1038/nn1555. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Renaud J, et al. Plexin-A2 and its ligand, Sema6A, control nucleus-centrosome coupling in migrating granule cells. Nature Neurosci. 2008;11:440–449. doi: 10.1038/nn2064. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.He H, Yang T, Terman JR, Zhang X. Crystal structure of the plexin A3 intracellular region reveals an autoinhibited conformation through active site sequestration. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:15610–15615. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906923106. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tong Y, et al. Structure and function of the intracellular region of the plexin-B1 transmembrane receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:35962–35972. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.056275. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takahashi T, Strittmatter SM. Plexina1 autoinhibition by the plexin sema domain. Neuron. 2001;29:429–439. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00216-1. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takahashi T, et al. Plexin-neuropilin-1 complexes form functional semaphorin-3A receptors. Cell. 1999;99:59–69. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80062-8. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oinuma I, Katoh H, Negishi M. Molecular dissection of the semaphorin 4D receptor plexin-B1-stimulated R-Ras GTPase-activating protein activity and neurite remodeling in hippocampal neurons. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:11473–11480. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3257-04.2004. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tong Y, et al. Binding of Rac1, Rnd1, and RhoD to a novel Rho GTPase interaction motif destabilizes dimerization of the plexin-B1 effector domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:37215–37224. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703800200. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gherardi E, Love CA, Esnouf RM, Jones EY. The sema domain. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2004;14:669–678. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.10.010. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stamos J, Lazarus RA, Yao X, Kirchhofer D, Wiesmann C. Crystal structure of the HGF β-chain in complex with the Sema domain of the Met receptor. EMBO J. 2004;23:2325–2335. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600243. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Niemann HH, et al. Structure of the human receptor tyrosine kinase met in complex with the Listeria invasion protein InlB. Cell. 2007;130:235–246. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.037. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koppel AM, Feiner L, Kobayashi H, Raper JA. A 70 amino acid region within the semaphorin domain activates specific cellular response of semaphorin family members. Neuron. 1997;19:531–537. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80369-4. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Müller KM, Arndt KM, Pluckthun A. Model and simulation of multivalent binding to fixed ligands. Anal. Biochem. 1998;261:149–158. doi: 10.1006/abio.1998.2725. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klostermann A, Lohrum M, Adams RH, Puschel AW. The chemorepulsive activity of the axonal guidance signal semaphorin D requires dimerization. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:7326–7331. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.13.7326. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koppel AM, Raper JA. Collapsin-1 covalently dimerizes, and dimerization is necessary for collapsing activity. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:15708–15713. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.25.15708. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Turner LJ, Hall A. Plexin-induced collapse assay in COS cells. Methods Enzymol. 2006;406:665–676. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)06052-6. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Merte J, et al. A forward genetic screen in mice identifies Sema3A(K108N), which binds to neuropilin-1 but cannot signal. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:5767–5775. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5061-09.2010. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu H, et al. Structural basis of Semaphorin-Plexin recognition and viral mimicry from Sema7A and A39R complexes with PlexinC1. Cell. 2010;142:749–761. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Toyofuku T, et al. FARP2 triggers signals for Sema3A-mediated axonal repulsion. Nature Neurosci. 2005;8:1712–1719. doi: 10.1038/nn1596. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gherardi E, et al. Structural basis of hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor and MET signalling. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:4046–4051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509040103. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aricescu AR, Lu W, Jones EY. A time- and cost-efficient system for high-level protein production in mammalian cells. Acta Crystallogr. D. 2006;62:1243–1250. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906029799. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chang VT, et al. Glycoprotein structural genomics: solving the glycosylation problem. Structure. 2007;15:267–273. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.01.011. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reeves PJ, Callewaert N, Contreras R, Khorana HG. Structure and function in rhodopsin: high-level expression of rhodopsin with restricted and homogeneous N-glycosylation by a tetracycline-inducible N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase I-negative HEK293S stable mammalian cell line. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:13419–13424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212519299. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walter TS, et al. A procedure for setting up high-throughput nanolitre crystallization experiments. Crystallization workflow for initial screening, automated storage, imaging and optimization. Acta Crystallogr. D. 2005;61:651–657. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905007808. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mayo CJ, et al. Benefits of automated crystallization plate tracking, imaging, and analysis. Structure. 2005;13:175–182. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.12.010. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. CrossRef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leslie AG. Recent changes to the MOSFLM package for processing film and image plate data. Joint CCP4 + ESF-EAMCB Newsletter on Protein Crystallography. 1992;26 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Evans P. Scaling and assessment of data quality. Acta Crystallogr. D. 2006;62:72–82. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905036693. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.CCP4 The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McCoy AJ, et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Cryst. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. CrossRef. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: building new software for automated crystallographic structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D. 2002;58:1948–1954. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902016657. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perrakis A, Morris R, Lamzin VS. Automated protein model building combined with iterative structure refinement. Nature Struct. Biol. 1999;6:458–463. doi: 10.1038/8263. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cowtan K. The Buccaneer software for automated model building. 1. Tracing protein chains. Acta Crystallogr. D. 2006;62:1002–1011. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906022116. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Blanc E, et al. Refinement of severely incomplete structures with maximum likelihood in BUSTER-TNT. Acta Crystallogr. D. 2004;60:2210–2221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904016427. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Davis IW, et al. MolProbity: all-atom contacts and structure validation for proteins and nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W375–W383. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm216. CrossRef. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stuart DI, Levine M, Muirhead H, Stammers DK. Crystal structure of cat muscle pyruvate kinase at a resolution of 2.6 Å. J. Mol. Biol. 1979;134:109–142. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(79)90416-9. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baker NA, Sept D, Joseph S, Holst MJ, McCammon JA. Electrostatics of nanosystems: application to microtubules and the ribosome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:10037–10041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181342398. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Larkin MA, et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Krissinel E, Henrick K. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;372:774–797. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.022. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gouet P, Courcelle E, Stuart DI, Metoz F. ESPript: analysis of multiple sequence alignments in PostScript. Bioinformatics. 1999;15:305–308. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/15.4.305. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Landau M, et al. ConSurf 2005: the projection of evolutionary conservation scores of residues on protein structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W299–W302. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki370. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.O’Callaghan CA, et al. BirA enzyme: production and application in the study of membrane receptor-ligand interactions by site-specific biotinylation. Anal. Biochem. 1999;266:9–15. doi: 10.1006/abio.1998.2930. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Trombetta ES, Parodi AJ. Quality control and protein folding in the secretory pathway. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2003;19:649–676. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.110701.153949. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schuck P. Size-distribution analysis of macromolecules by sedimentation velocity ultracentrifugation and Lamm equation modeling. Biophys. J. 2000;78:1606–1619. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76713-0. Medline CrossRef. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.