Abstract

The freshwater bryozoan Fredericella sultana (Blumenbach) is the most common invertebrate host of the myxozoan parasite Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae, the causative agent of proliferative kidney disease in salmonid fish. Culture media play an important role in hatching of statoblasts and maintaining clean bryozoan colonies for Malacosporea research. We developed a novel culture medium, Bryozoan Medium C (BMC), for the cultivation and maintenance of F. sultana under laboratory conditions. Statoblasts of F. sultana were successfully hatched to produce transparent-walled, specific pathogen-free (SPF) colonies that were maintained >12 months in BMC at pH 6.65. Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae was successfully transmitted from infected brown trout, Salmo trutta L., to newly hatched F. sultana colonies in BMC, then from the infected bryozoan to SPF brown trout. This study demonstrated the utility of BMC (pH 6.65) for hatching statoblasts, long-term cultivation of clean and transparent bryozoan colonies and maintenance of the Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae life cycle in the laboratory for molecular genetic research and other studies such as host–parasiteinteraction.

Keywords: bryozoan, cultivation, Fredericella sultana, maintenance, medium, Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae

Introduction

Members of the Phylum Bryozoa are generally small, sessile invertebrates that live on submerged surfaces, with most freshwater bryozoans grouped in the class Phylactolaemata (Wood et al. 1998). During warm months, bryozoans are found in almost any lake or stream that have suitable attachment sites, such as tree branches, roots, rocks, pilings or docks (Wood 2009). Bryozoans are typically colonial, consisting of connected zooid subunits, each of which has its own independent tentacular lophophore mouth, gut, muscles, nervous and reproductive systems, but adjacent zooids share certain tissues and fluids that physiologically unify bryozoan colonies (Wood et al. 1998; Wood & Okamura 2005). Bryozoans feed by filtering water for organic particles, small microorganisms such as diatoms and other unicellular algae that they capture with ciliated tentacles (Wood et al. 1998). Colonies typically reproduce asexually, through two routes: colony fragmentation or statoblast formation. Colony fragments can adhere to new substrates and grow to form new colonies (Buchsbaum et al. 1987). Bryozoans of the class Phylactolaemata can form encapsulated, seed-like statoblasts, which remain dormant and can withstand drying and freezing; when conditions are favourable, the statoblasts germinate to form a new colony (Wood & Okamura 2005).

One of the most common freshwater bryozoans is Fredericella sultana, which grows by budding zooids that form tubular and branching colonies (Okamura & Wood 2002). In addition to reproduction via statoblasts, F. sultana can undergo sexual reproduction and produces larvae in early summer (Tops, Hartikainen & Okamura 2009). Fredericella sultana colonies grow rapidly during spring, form large colonies by summer and overwinter either as living colonies or statoblasts (Wood 1973; Bushnell & Rao 1974; Tops et al. 2004; Morris & Adams 2006). The colonies have a tough, chitinous outer wall and are attached to submerged surfaces (Wood & Okamura 2005). Generally, field-collected bryozoans colonies are encrusted with opaque, inorganic particles in the body wall and sometimes associate with numerous ciliates, which hinder examination of developing parasite stages within the bryozoans (Pennak 1989; Morris & Adams 2006; Hartikainen & Okamaura 2012). Clean and ciliate-free bryozoan colonies are very important to examine the malacosporean parasite developmental stages (Morris, Morris & Adams 2002).

Proliferative kidney disease (PKD) significantly affects both farmed and wild salmonid fish in Europe and North America, causes economic losses and endangers wild fish populations (Feist et al. 2001; El-Matbouli & Hoffmann 2002). PKD is caused by the myxozoan parasite Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae (Myxozoa: Malacosporea). Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae spores develop in the kidney tubules of infected fish are released via urine to infect bryozoan hosts (Morris & Adams 2006; Grabner & El-Matbouli 2008). The life cycle of T. bryosalmonae requires two hosts: a vertebrate (salmonid fish) and an invertebrate (freshwater bryozoan) (Canning et al. 2000; Feist et al. 2001; Grabner & El-Matbouli 2008).

Fredericella sultana is the most common invertebrate host of T. bryosalmonae (Anderson, Canning & Okamura 1999; Feist et al. 2001; Grabner & El-Matbouli 2008). Within F. sultana, the parasite starts its development as single cells associated with the bryozoan body wall and then proliferates into spore-producing sacs in the body cavity; spores are released into the water, where they can infect fish and cause PKD (Longshaw et al. 2002; Tops & Okamura 2003; Morris & Adams 2006; Tops, Lockwood & Okamura 2006).

Bryozoan development is affected primarily by water temperature, pH, calcium and magnesium (Ricciardi & Reiswig 1994; Økland & Økland 2001); with lesser influence from potassium, sulphate and nitrate (Schopf & Manheim 1967; Økland & Økland 2001; Morris et al. 2002; Hartikainen et al. 2009). Several water chemistries and growth media have been used for short-term culture and maintenance of bryozoans in aquarium systems: artificial freshwater medium (0.35 mm CaSO4, 0.5 mm KCl, 0.5 mm MgSO4, 0.1 mm NaHCO3), Chalkley's medium (1.7 mm NaCl, 50 μm KCl, 50 μm CaCl2) and dechlorinated tap water (Wood 1996; Morris et al. 2002; Tops et al. 2004; McGurk et al. 2006; Grabner & El-Matbouli 2008).

Our objectives were to establish and optimize a medium for hatching F. sultana statoblasts, production of SPF colonies and long-term cultivation and maintenance of clean bryozoan colonies. We succeeded in reaching these goals and were able to establish the whole life cycle of T. bryosalmonae within a laboratory setting. Furthermore, application of optimized medium will facilitate a more detailed chronological study of parasite development in both hosts and collection of developmental stages of the parasite that are required for molecular genetic studies and other research activities.

Materials and methods

Collection of colonies and preparation of the culturing system

Fredericella sultana colonies were collected in April 2011 from the Lohr River, Germany (50°01′08′′N; 09°32′43′′E) at depths of 20–100 cm attached to roots of alder trees. Colonies were placed in containers filled with aerated river water and transported to the laboratory at the Clinical Division of Fish Medicine, University of Veterinary Medicine, Vienna, Austria.

A range of media were prepared (A–D, Table 1): each had different concentrations of calcium chloride dihydrate (CaCl2 H2O), magnesium chloride hexahydrate (MgCl2 6H2O), potassium nitrate (KNO3), sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3), magnesium sulphate heptahydrate (MgSO4 7H2O) and sodium chloride (NaCl) and each at different pH (4.0, 5.65, 6.65, 7.65 and 9.0). Media were aerated overnight before use. Concentrated (100×) stock solutions of medium C (Bryozoan Medium C ‘BMC’) components were prepared in sterile 500-mL bottles (Table 2) and stored at 4 °C. Working solutions of BMC were prepared by adding 10 mL of each of the six stock component solutions to 9.940 L Milli-Q water, and the final solution mixed thoroughly.

Table I.

Component concentrations of the four media

| Components | Concentrations of media (L−1) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medium A (mm) | Medium B (mm) | Medium C (mm) | Medium D (mm) | |

| CaCl2·H2O | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.025 |

| MgCl2·6H2O | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.05 | 0.025 |

| KNO3 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.0075 |

| NaHCO3 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.125 |

| MgSO4·7H2O | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.02 |

| NaCl | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 0.85 |

Table 2.

Component recipe for 100× stock solution of Bryozoan Medium C

| Components | Formula weight | Final concentration in stock solution (m) | Grams for 500 mL of 100× stock solution (g) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CaCl2·H2O | 147.02 | 0.1 | 7.35 |

| MgCl2·6H2O | 203.31 | 0.05 | 5.08 |

| KNO3 | 101.11 | 0.03 | 1.516 |

| NaHCO3 | 84.01 | 0.25 | 10.50 |

| MgSO4·7H2O | 246.48 | 0.04 | 4.92 |

| NaCl | 58.44 | 1.7 | 49.67 |

Statoblast hatching experiments

Free statoblasts were dissected from F. sultana colonies with fine needles and forceps, collected by pipette and pooled into a single container. Media (A–D) were tested at the 5 pH values (4.0, 5.65, 6.65, 7.65 and 9.0), in duplicate, in a total of 40–12 cm plastic Petri-plates, each of which contained 30 statoblasts. All plates were stored at 4 °C for 2 weeks in the dark and subsequently incubated at 15 °C for a week. After attachment of statoblasts to the dish-surface, each pair of plates was transferred to 2-L containers filled with the same medium, at the same pH, and held at 18 °C with slow aeration and illumination. After statoblasts hatched, three punctures were made in each plate to enhance circulation of the medium, and the plate placed upside down in racks, back in the same containers.

We compared statoblast hatch rates of our media with Chalkley's medium and dechlorinated tap water, which were prepared according to the methods of McGurk et al. (2006) and Grabner & El-Matbouli (2008), with statoblasts incubated and maintained as for our media.

Colony cultivation experiments

Small pieces (3–4) of alder tree roots with mature F. sultana colonies were glued to each of 20–12 cm plastic Petri-dishes. The dishes were then held singly in 5-L containers, each of which contained one of the four media, at one of the five pH values, and held at 18 °C with slow aeration and illumination. Growth in the different media was compared with F. sultana colonies held in Chalkley's medium or 1-week old aerated dechlorinated tap water (maintained as for the test media).

Maintenance of colonies

Bryozoans, both from fresh hatched statoblasts and mature colonies, were maintained according to Grabner & El-Matbouli (2008). Briefly, 5 algal species (Cryptomonas ovata, Cryptomonas sp., Chlamydomonas sp., Chlamydomonas reinhardii, Synechococcus sp.) were cultured in sterile Guillard's WC-Medium. Approximately, 50 mL of C. ovata and 12 mL of the other four algae were added to the 2-L hatching experiments, every second day. Similarly, 125 mL of C. ovata and 30 mL of the other four algae were added to the 5-L mature colony experiments, every second day. The total medium of each container was replaced weekly with fresh medium. Bryozoan colonies were observed daily using a dissecting microscope.

Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae life cycle experiments

BMC (pH 6.65) was used for the T. bryosalmonae life cycle experiment, as it gave best results for statoblast hatching and colony maintenance (see Results).

Fredericella sultana colonies naturally infected with T. bryosalmonae were collected from the Lohr River, Germany and placed in 8-L aquaria with BMC (pH 6.65) and held at 18 °C. Three SPF brown trout (4–5 cm long) were cohabitated for 8 h per day for 14 days with the infected F. sultana colonies. During this period, bryozoan colonies were fed daily as previously mentioned. After infection, fish were placed in 20-L aquaria with flow-through water.

Eight weeks post-infection, the three infected brown trout were cohabitated for 8 h per day for 14 days with laboratory-hatched, 2-month-old SPF F. sultana in an 8-L aquarium filled with BMC (pH 6.65) at 18 °C. After 8-h cohabitation, fish were transferred to a 10-L aquarium with spring water at the same temperature and fed with salmonid feed. The bryozoan colonies were fed with algae as mentioned above, and the entire medium replaced once per week.

Results

Statoblast hatching

Table 3 shows the number of the 30 statoblasts that hatched in each of the four media tested, at each of five pH values. Medium BMC at pH 6.65 produced the best hatching result: 8–10 statoblasts/plate (33%) hatched (Fig 1) after 2 weeks of incubation. Fewer hatched in BMC at pH 5.65 or 7.65, after 4 weeks, or 5–6 weeks in medium D at pH 6.65. No statoblasts hatched in media C and D at pH 4.0 or 9.0, or in media A and B at any pH. The pH of BMC (pH 6.65) was not significantly (+0.08) affected by using cultured algae species for feeding bryozoans. Hatched statoblasts started to colonize onto Petri dish plates and proliferated into zooids. Initially, hatched colonies developed 2–3 zooids. Six weeks post-hatching; colonies were growing at a rate of 12–14 zooids per month and produced statoblasts. We maintained the hatched colonies in BMC (pH 6.65) for more than 1 year.

Table 3.

Hatching rate of Fredericella sultana statoblasts in media (A–D) at different pH values. Each trial run with duplicate plates

| Media | Hatching rate of Fredericella sultana statoblasts (number of hatched statoblasts/total number of statoblasts) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH 4.0 | pH 5.65 | pH 6.65 | pH 7.65 | pH 9.0 | |||||||

| Plate 1 | Plate 2 | Plate 1 | Plate 2 | Plate 1 | Plate 2 | Plate 1 | Plate 2 | Plate 1 | Plate 2 | ||

| A | NH | NH | NH | NH | NH | NH | NH | NH | NH | NH | |

| B | NH | NH | NH | NH | NH | NH | NH | NH | NH | NH | |

| C | NH | NH | 1/30 | 2/30 | 8/30 | 10/30 | 2/30 | 1/30 | NH | NH | |

| D | NH | NH | 0/30 | 1/30 | 1/30 | 1/30 | 1/30 | 0/30 | NH | NH | |

NH, not hatched.

Figure 1.

Three-week-old Fredericella sultana zooid, hatched in the laboratory in bryozoan medium C (pH 6.65) (x100).

Viability and maintenance of mature Fredericella sultana colonies

Table 4 shows the survival and growth of mature F. sultana colonies under the different media and pH conditions. BMC at pH 6.65 gave the best results, and colonies survived and thrived for >12 months. Ciliates such as Vorticella species and Carchesium species were found initially on field-collected F. sultana colonies; however, those colonies were ciliate-free after 2 weeks of incubation in BMC (pH 6.65). The colonies were clean and transparent (Fig 2), proliferated and started to make new zooids. Colonies grew 24–31 zooids per month and produced statoblasts.

Table 4.

Survival of Fredericella sultana colonies in media (A–D) at different pH values

| Media | Time period of maintenance of mature Fredericella sultana colonies | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH 4.0 (weeks) | pH 5.65 (months) | pH 6.65 (months) | pH 7.65 (months) | pH 9.0 (weeks) | ||

| A | 4–5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4–5 | |

| B | 4–5 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 4–5 | |

| C | 4–5 | 4 | >12* | 3 | 4–5 | |

| D | 4–5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4–5 | |

Colonies are still maintaining and growing in BMC under laboratory conditions until now.

Figure 2.

Clean and transparent laboratory-cultured Fredericella sultana colony, showing tentacles (x40).

In other media and pH, colonies could be maintained 3–4 months in BMC (pH 5.65 or 7.65) and 2 months in medium D (pH 5.65, 6.65, 7.65). While colonies survived 4–5 weeks at pH 4.0 or 9.0 in all media, they subsequently suffered massive mortalities. Survival of F. sultana colonies was poor (2–3 months) in media A or B at pH 5.65, 6.65 and 7.65.

Hatching of statoblasts and maintenance of colonies in Chalkley's medium or in dechlorinated tap water

Of 30 statoblasts, 2–3 statoblasts hatched after 4–5 weeks of incubation in Chalkley's medium, while 1–2 statoblasts hatched after 6–7 weeks of incubation in dechlorinated tap water. Colonies survived in Chalkley's medium for up to 6 months and in dechlorinated tap water for up to 4–5 months.

Infection of SPF Fredericella sultana colonies with Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae

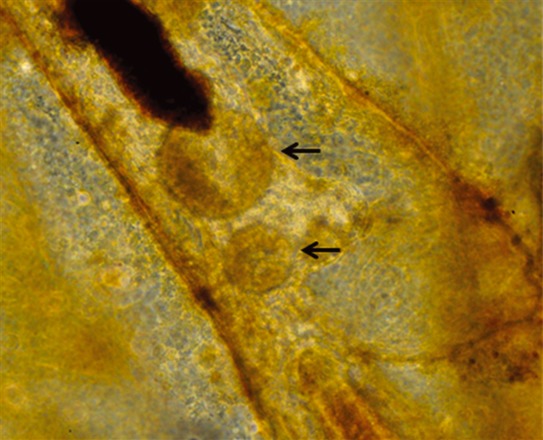

Four weeks post-exposure to infected brown trout, free swirling spores were observed in the body cavity of SPF F. sultana colonies. Fifty per cent of the colonies were infected with T. bryosalmonae. During the following weeks, more zooids within the same colony of bryozoan showed overt infections with mature sacs (Fig 3), and spores were seen floating in the metacoel. Typically, 2–6 mature sacs were observed in zooids. Infected colonies did not produce any statoblasts.

Figure 3.

Two spore sacs of Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae (arrows) within a laboratory-infected Fredericella sultana colony (x100).

Discussion

Reliable cultivation and maintenance of F. sultana is regarded as an essential basis for establishment of the T. bryosalmonae life cycle in the laboratory (Grabner & El-Matbouli 2009). Different culture media have been used for maintenance of bryozoans: artificial freshwater medium, Chalkley's medium or freshwater protozoan culture medium and dechlorinated tap water (Morris et al. 2002; McGurk 2005; Grabner & El-Matbouli 2008). Alternatively, bryozoans can be cultivated using a recirculating aquarium ‘mesocosm’ culture system (Wood 1971, 1996), modified by Tops et al. (2004). However, these systems have disadvantages that include growth of chironomid larvae and ciliates, a requirement of natural water source to seed the tanks and the use of goldfish in the culture system. Low nutrient microcosms decrease the growth and increase the mortality of F. sultana colonies, and vice versa (Hartikainen et al. 2009). In the present study, we observed mortalities of F. sultana colonies in dechlorinated tap water, which we suspect is too mineral-poor for long-term maintenance of bryozoans. A clear requirement for strong colony growth is constant nutrient concentrations in the culture medium along with proper feeding of algae. Grabner & El-Matbouli (2008) used autoclaved mud from a fish pond to provide sediment-containing organic material to promote growth of bacteria and protozoa as nutrition for the bryozoa, whereas McGurk (2005) added higher concentrations of algae and protozoa directly to bryozoans. While both of these supplementation methods work, they have disadvantages that include accumulation of mud or algae particles on the surface of the bryozoans and the Petri dish plates, which increases ciliate accumulation and makes colonies less transparent.

In the present study, we fed bryozoans with cultured algae, grown in algal medium (CaCl2, MgSO4, NaHCO3, K2HPO4, NaNO3, Na2SiO3 and vitamins such as thimamine, biotin, cyanocobalamin). Introduction of these cultured algae did not show any adverse effects on the growth of colonies.

We also tested various component concentrations and pH in the medium in which the bryozoans were grown. Calcium and magnesium are known to be important components of natural water bodies that support bryozoans (Økland & Økland 2001). Calcium plays a pivotal role in the physiology and biochemistry of many cellular processes (Berridge, Bootman & Lipp 1998), and specifically, Ca2+ ions are essential components of the bryozoan body wall (Økland & Økland 2001; Wood 2009). Magnesium is an essential mineral for cell division, nucleic acids and protein synthesis (Maguire & Cowan 2002). Therefore, calcium and magnesium likely play an important role in statoblast hatching and colony growth.

Fredericella sultana naturally grows in the calcium and magnesium concentrations of 0.7–52.5 and 0.0–7.3 mg L−1, respectively (Økland & Økland 2001). We tested calcium concentrations of 147, 73.5, 14.7 and 3.65 mg L−1 and magnesium concentrations of 40, 20, 10 and 5 mg L−1 in media A, B, C and D, respectively. Statoblasts did not hatch in media A or B, while hatching rate was poor and slow in medium D. Hatching rate and speed was best in medium C (‘BMC’). We could not compare our hatching rate with previous studies, which used artificial freshwater medium and Chalkley's medium as these data were not recorded (Morris et al. 2002; McGurk et al. 2006). We found statoblast hatching rates were poor and slow in both Chalkley's medium and dechlorinated tap water, which suggests that both low and high component concentrations affect hatching of statoblasts.

Sodium chloride reduces the growth of protozoa such as ciliates (Ion et al. 2011). Ciliate contamination (Rotaria and Vorticella species) is among the problems in growing bryozoan colonies (Morris et al. 2002). We observed Vorticella species and Carchesium species, initially in our field-collected colonies. However, colonies became ciliate-free after incubating in BMC, which we suspect is a direct result of the presence of NaCl (100 mg L−1) in the BMC suppressing ciliate growth.

The pH is known to affect bryozoan growth: Økland & Økland (1986) demonstrated that acidic conditions have negative effects on bryozoa. We showed that pH played an important role in success of statoblast hatching and long-term maintenance of bryozoan colonies. Statoblasts did not hatch, and viability of colonies was not maintained in BMC at pH 4.0 or pH 9.0, showing that neither low nor high pH values are suitable for hatching statoblasts and growth of bryozoan colonies; moderately high or low pH (5.65, 7.65) had low hatching rates. We found that pH 6.65 BMC was optimum for hatching, viability and transparency of bryozoan colonies over the long term (>12 months).

We found that 33% of statoblasts had hatched after 2 weeks of incubation in BMC (pH 6.65). This rate was slower than the rate observed by Hartikainen et al. (2009), who report statoblasts hatched after 4 days of incubation in artificial pond water. We suspect that some untested factor such as age, development or environmental history or water chemistry may be the cause of slow hatching rate of statoblasts in BMC (Bushnell & Rao 1974). We determined there was no significance difference in the hatching rate of statoblasts that had been stored at 4 °C for 2 weeks or 5 weeks in the dark.

In BMC at pH 6.65, we observed a colony growth rate of 12–14 zooids per month, after 6 weeks post-hatching, with no colony mortality. This rate is slower than that reported by Hartikainen et al. (2009) who observed hatched colonies had developed 9–11 zooids after 15 days of incubation in artificial pond water, but with some mortality over 20 days, in high nutrient microcosms. The slower growth rate that we observed may be due to some insufficiency arising from the switch from a natural river environment to BMC and feeding with a limited set of algae species.

We consider that a hybrid approach may be best for growth and maintenance of bryozoans in the laboratory: a combination of the aquarium bryozoan culture system (goldfish system) and our clean BMC system. The goldfish system is suitable for generating large-scale bryozoan growth (Wood 1996; Tops et al. 2004; Hartikainen et al. 2009; Hartikainen & Okamaura 2012) but does not produce SPF bryozoans because of the use of natural pond water and gold fish. Our BMC system has lower bryozoan growth rates, but it is a clean system that produces SPF colonies essential for maintaining and studying malacosporean parasite life cycles in the laboratory. We showed that a system that contains BMC (pH 6.65) is suitable for transmission of T. bryosalmonae from infected brown trout to SPF F. sultana and supports the further development of the parasite in bryozoan colony.

In conclusion, we have shown that BMC (pH 6.65) can be used for rapid hatching of bryozoan statoblasts, long-term cultivation and maintenance of clean colonies. This facilitates the establishment of the T. bryosalmonae life cycle under laboratory-controlled conditions, to permit study of host–pathogen interaction and also collection of parasite developmental stages for molecular genetic studies and other research activities.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF), Project no. P 22770-B17. We are thankful to DI Bernhard Eckel for collecting of bryozoan samples, Mr Mathias Stock for technical assistance and Dr Stephen Atkinson for editorial input to the manuscript.

References

- Anderson CL, Canning EU, Okamura B. Molecular data implicate bryozoans as hosts for PKX (Phylum Myxozoa) and identify a clade of bryozoan parasites within the Myxozoa. Parasitology. 1999;119:555–561. doi: 10.1017/s003118209900520x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge MJ, Bootman MD, Lipp P. Calcium: a life and death signal. Nature. 1998;395:645–648. doi: 10.1038/27094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchsbaum R, Buchsbaum M, Pearse J, Pearse V. Animals without Backbones. 3. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1987. pp. 249–290. [Google Scholar]

- Bushnell JH, Rao KS. Dormant or quiescent stages and structures among the ectoprocta: physical and chemical factors affecting viability and germination of statoblasts. Transactions of the American Microbiology Society. 1974;93:524–543. [Google Scholar]

- Canning EU, Curry A, Feist SW, Longshaw M, Okamura B. A new class and order of myxozoans to accommodate parasites of bryozoans with ultrastructural observations on Tetracapsula bryosalmonae. Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 2000;47:456–468. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2000.tb00075.x. (PKX organism) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Matbouli M, Hoffmann RW. Influence of water quality on the outbreak of proliferative kidney disease-field studies and exposure experiments. Journal of Fish Diseases. 2002;25:459–467. [Google Scholar]

- Feist SW, Longshaw M, Canning EU, Okamura B. Induction of proliferative kidney disease (PKD) in rainbow trout Oncorhynchus mykiss via the bryozoan Fredericella sultana infected with Tetracapsula bryosalmonae. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms. 2001;45:61–68. doi: 10.3354/dao045061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabner DS, El-Matbolui M. Comparison of the susceptibility of brown trout (Salmo trutta) and four rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) strains to the myxozoan Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae, the causative agent of proliferative kidney disease (PKD) Veterinary Parasitology. 2009;165:200–206. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2009.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabner DS, El-Matbouli M. Transmission of Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae (Myxozoa: Malacosporea) to Fredericella sultana (Bryozoa: Phylactolaemata) by various fish species. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms. 2008;79:133–139. doi: 10.3354/dao01894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartikainen H, Okamaura B. Castrating parasites and colonial hosts. Parasitology. 2012;139:547–556. doi: 10.1017/S0031182011002216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartikainen H, Johnes P, Moncrieff C, Okamura B. Bryozoan populations reflect nutrient enrichment and productivity gradients in rivers. Freshwater Biology. 2009;54:2320–2334. [Google Scholar]

- Ion S, Cristea V, Grecu I, Bocioc E, Popescu A, Coada MT. Influence of environmental conditions in ichthyophthiriasis trigger to the Europeans catfish juveniles (Silurus Glanis) stocked into a production system with partially reused water. Animal Science and Biotechnologies. 2011;44:19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Longshaw M, Le Deuff RM, Harris AF, Feist SW. Development of proliferative kidney disease in rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss (Walbaum), following short-term exposure to Tetracapsula bryosalmonae infected bryozoans. Journal of Fish Diseases. 2002;25:443–449. [Google Scholar]

- Maguire ME, Cowan JA. Magnesium chemistry and biochemistry. BioMetals. 2002;15:203–210. doi: 10.1023/a:1016058229972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGurk C. Stirling, Scotland: University of Stirling; 2005. Culture of malacosporeans (Myxozoa) and development of control strategies for proliferative kidney disease. PhD thesis. [Google Scholar]

- McGurk C, Morris DJ, Auchinachie NA, Adams A. Development of Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae (Myxozoa: Malacosporea) in bryozoan hosts (as examined by light microscopy) and quantitation of infective dose to rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss. Veterinary Parasitology. 2006;135:249–257. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2005.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris D, Adams A. Proliferative, presaccular stages of Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae (Myxozoa: Malacosporea) within the invertebrate host Fredericella sultana (Bryozoa: Phylactolaemata) Journal of Parasitology. 2006;92:984–989. doi: 10.1645/GE-868R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris DJ, Morris DC, Adams A. Development and release of a malacosporea (Myxozoa) from Plumatella repens (Bryozoa: Phylactolaemata) Folia Parasitologica. 2002;49:25–34. doi: 10.14411/fp.2002.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura B, Wood TS. Bryozoans as hosts for Tetracapsula bryosalmonae, the PKX organism. Journal of Fish Diseases. 2002;25:469–475. [Google Scholar]

- Økland KA, Økland J. The effects of acid deposition on benthic animals in lakes and streams. Experientia. 1986;42:471–486. [Google Scholar]

- Økland KA, Økland J. Freshwater bryozoans (Bryozoa) of Norway II: distribution and ecology of two species of Fredericella. Hydrobiologia. 2001;459:103–123. [Google Scholar]

- Pennak RW. Freshwater invertebrates of the United States. In: Pennak RW, editor. Protozoa to Mollusca. 3rd edn. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1989. p. 628. [Google Scholar]

- Ricciardi A, Reiswig HM. Taxonomy, distribution, and ecology of the freshwater bryozoans (Ectoprocta) of eastern Canada. Canadian Journal of Zoology. 1994;72:339–359. [Google Scholar]

- Schopf TJM, Manheim FT. Chemical composition of ectoprocta (Bryozoa) Journal of Paleontology. 1967;41:1197–1225. [Google Scholar]

- Tops S, Okamura B. Infection of bryozoans by Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae at sites endemic for salmonid proliferative kidney disease. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms. 2003;57:221–226. doi: 10.3354/dao057221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tops S, Baxa DV, McDowell TS, Hedrick RP, Okamura B. Evaluation of malacosporean life cycles through transmission studies. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms. 2004;60:109–121. doi: 10.3354/dao060109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tops S, Lockwood W, Okamura B. Temperature-driven proliferation of Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae in bryozoan hosts portends salmonid declines. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms. 2006;70:227–236. doi: 10.3354/dao070227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tops S, Hartikainen HL, Okamura B. The effects of infection by Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae (Myxozoa) and temperature on Fredericella sultana (Bryozoa) International Journal for Parasitology. 2009;39:1003–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood TS. Laboratory culture of fresh-water ectoprocta. Transactions of the American Microbiology Society. 1971;90:92–94. [Google Scholar]

- Wood TS. Colony development in species of Plumatella and Fredericella (Ectoprocta: Phylactolaemata) In: Boardman RS, Cheetham A, Oliver WAJ, editors. Development and Function of Animal Colonies Through Time. Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania: Dowden, Hutchinson and Ross; 1973. pp. 395–432. [Google Scholar]

- Wood TS. Aquarium culture of freshwater invertebrates. The American Biology Teacher. 1996;58:46–50. [Google Scholar]

- Wood TS. Bryozoans. In: Thorp JH, Covich AP, editors. Ecology and Classification of North American Freshwater Invertebrates. 3rd edn. UK: Elsevier Academic Press; 2009. pp. 437–454. [Google Scholar]

- Wood TS, Okamura B. Scientific publication 63. In: Wood TS, Okamura B, Sutcliffe DW, editors. A New Key to the Freshwater Bryozoans of Britain, Ireland and Continental Europe, with notes on their Ecology. Ambleside: Freshwater Biology Association; 2005. p. 113. [Google Scholar]

- Wood TS, Wood LJ, Geimer G, Massard J. Freshwater bryozoans of New Zealand: a preliminary survey. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research. 1998;32:639–648. [Google Scholar]