Abstract

Patient age can impact selection of the optimal antiepileptic drug for a number of reasons. Changes in brain physiology from neonate to elderly, as well as changes in underlying etiologies of epilepsy, could potentially affect the ability of different drugs to control seizures. Unfortunately, much of this is speculative, as good studies demonstrating differences in efficacy across age ranges do not exist. Beyond the issue of efficacy, certain drugs may be more or less appropriate at different ages because of differing pharmacokinetics, including changes in hepatic metabolism, absorption, and elimination. Lack of appropriate drug formulations (such as liquid forms) may be a barrier to using drugs in the very young. Finally, some serious adverse events are seen either exclusively or preferentially at different ages.

The management of epilepsy can be difficult owing to the inherently complex nature of the disorder. Pharmacotherapy with antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) is the most common treatment approach. Thirteen new AEDs have been approved by the FDA since 1993. The increase in available drugs provides more options for the prescribing physician, but it has also increased the complexity of drug selection. Determining which of the many AEDs is the best “fit” for a patient can be a challenge. It is increasingly taught that AED selection can be “personalized,” based on patient characteristics such as age, gender, and the presence of comorbidities. These patient characteristics may be related to the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of AEDs and can help determine the most appropriate drug therapy for an individual.

In this review, we focus on age as a factor in selecting the most appropriate AED. There are a number of reasons why age may be a factor in AED selection. Most physicians are aware that many seizure types and syndromes have specific ages of onset, and because many AEDs are more effective for subsets of seizure types and syndromes, some drugs will be more appropriate for individuals of certain ages. For example, ethosuximide, is a drug used to treat absence seizures, a seizure type found most commonly in children and adolescents. This issue will not be discussed further, as it relates more to drug selection based on seizure type. But there may also be other issues that make some drugs more or less appropriate or useful at different ages, even if the seizure type and syndrome are the same. It is these issues that will be discussed in the current review. Examples include changes in brain function at different ages, changes in underlying epilepsy etiology, changes in pharmacokinetics, and changes in frequency and types of adverse effects. There is a great need for data regarding AED efficacy relative to age from randomized control trials (RCTs) to guide clinical decision-making, but these types of studies are few. Until those studies are completed, clinicians may give consideration to patient age when determining a treatment plan for epilepsy, but there will be a paucity of scientifically rigorous data to guide them.

Differences in Underlying Brain Function

How does the brain differ at different ages, and how can those differences impact drug selection? In newborn infants, seizures are different that those seen at later ages, both semiologically and possibly in regards to underlying pathophysiology and development of neurotransmission. Seizures can present as focal or migrating and multifocal (1) and may be subtle and fragmented. The circuitry in the immature brain is different. The infant brain shows an overdevelopment of excitatory neurotransmission, and a relative underdevelopment of inhibitory transmission. Moreover, even the traditional neurotransmitter GABA may behave differently in the neonatal brain, activating excitatory rather than inhibitory pathways (2). Clearly, these and other differences related to brain maturation might impact on the effect of antiepileptic drugs. Physicians continue to favor older AEDs to treat neonatal seizures, with phenobarbital being the drug of choice, followed by phenytoin and then benzodiazepines (3). Several of these choices (phenobarbital and the benzodiazepines) work by GABA mechanisms. One study suggested that 50% of neonatal seizures are unresponsive to phenobarbital or phenytoin monotherapy (4). Unfortunately, there are few rigorous studies at this age; therefore it is unknown whether other drugs might work better. A recent survey indicates that pediatricians and pediatric neurologists are turning to newer AEDs for treatment of neonates, despite there being no high quality evidence of efficacy, or assessment of pharmacokinetic properties in some cases (5).

The brains of children continue to mature from infancy to adulthood. As maturation occurs, there is an increase in myelinization, the limbic system develops, and the dendritic system also matures. In fact, this is even recognizable by changes in semiology of partial seizures (6). In the elderly, anatomic and electrophysiological changes occur in the mesial temporal lobe, making temporal lobe epilepsy more likely. In addition, hippocampal cell loss has been seen in animal models, as well as synaptic loss in the dentate gyrus. Recent studies suggesting a link between Alzheimer disease and epilepsy raise the possibility that selective loss or dysfunction of particular classes of neurons and, in particular, brain regions may contribute to seizures, including subtle seizure activity that is easily confused with amnestic behavior (7). Whether these unique seizure semiologies and pathophysiologies will respond selectively to particular AEDs will require extensive new experimental and clinical investigations.

Differences in Underlying Etiology of Focal Seizures

To date, we have been taught that drug selection should be based on seizure type (for example focal versus generalized), but not etiology. The etiology of epilepsy is distinctive at different ages. The incidence of epilepsy has a bimodal distribution, with greatest risk in infants and the elderly (8). Infants are at risk for seizures as a result of injuries caused by the birthing process, such as trauma, hyperischemic insults, intracranial hemorrhages, and infection. Congenital brain anomalies and genetic and metabolic disorders may also cause neonatal seizures (9, 10). New onset epilepsy in the elderly is most often a result of stroke, degenerative disease, tumor, trauma, or infection, although up to 50% of cases are idiopathic (10).

More studies are needed to define a correlation between etiology of epilepsy and AED efficacy. However, there is clear evidence of such a link, for example, between the etiology of infantile spasms and the efficacy of vigabatrin. Ninety-five percent of infants with TSC treated with vigabatrin have complete cessation of infantile spasms, compared with 54% of those without TSC (11). It is unclear why efficacy is higher in those with TSC. This distinction suggests that in some cases, etiology may be predictive of AED efficacy.

Differences in Efficacy

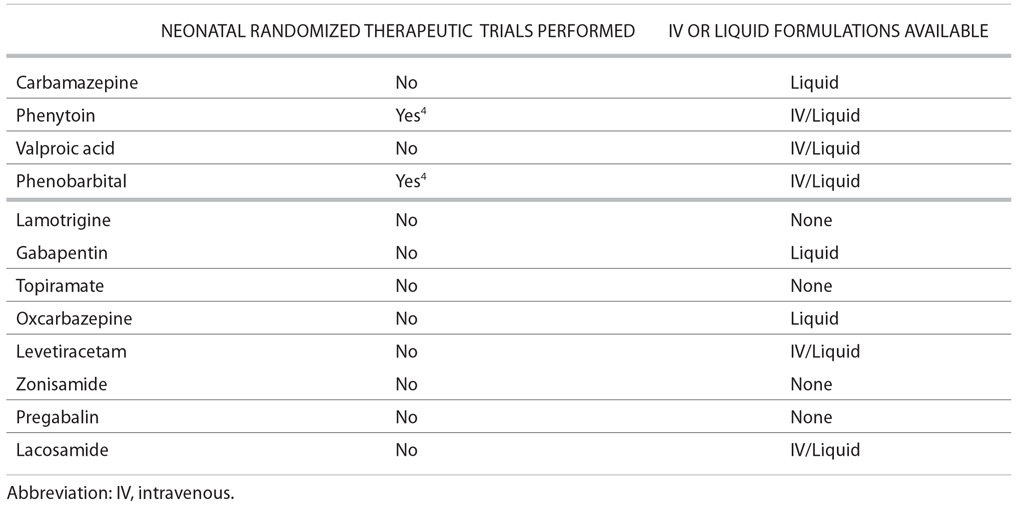

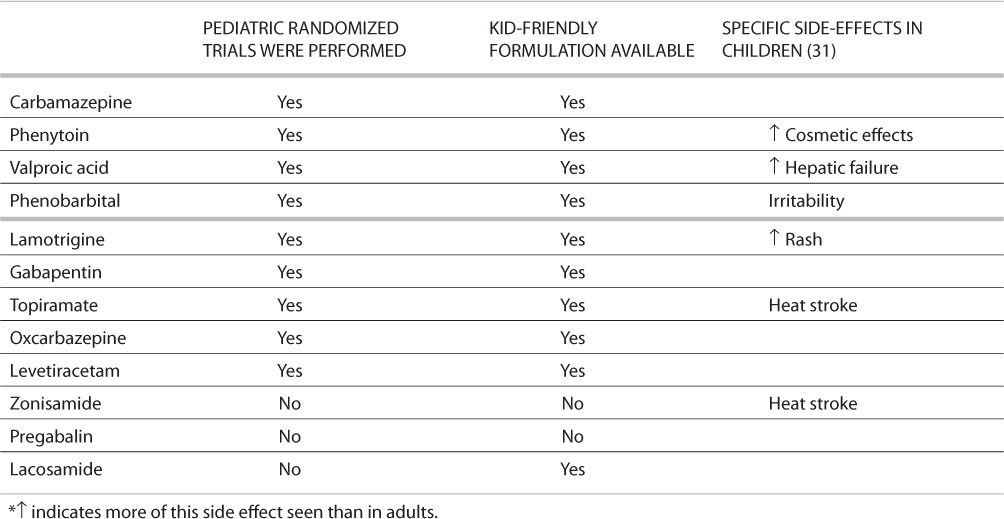

The issues above (changes in the brain as we age and changes in underlying seizure etiologies) could mean that some drugs are more or less efficacious at certain ages irrespective of seizure type. Unfortunately, there is a lack of clinical evidence demonstrating the most efficacious AEDs by age group to guide clinical decision-making. Numerous RCTs have assessed the efficacy of AEDs in either adults or children (12, 13). At present, not all antiepileptic drugs have undergone randomized clinical trials in neonates, children, or the elderly, which would demonstrate efficacy at these ages. For specific information on which AEDs have undergone specific trials, see Tables 1 and 2. It has been generally accepted that AEDs that work for partial seizures in adults also work in children. In fact, the European Medicinals Agency (the European equivalent of the FDA) has stated that “focal epilepsies in children older than 4 years old have a similar clinical expression to focal epilepsies in adolescents and adults. In refractory focal epilepsies … the results of efficacy trials performed in adults could to some extent be extrapolated to children provided the dose is established.…” (14). Even if this is taken as fact, there is still a possibility that the relative efficacy may differ at different ages. Few studies have included multiple age groups to compare the relative effects of AEDs. The largest RCT examining some age-treatment interactions was the 2007 Standard and New Antiepileptic Drugs study (SANAD) (15). This study assessed the efficacy of carbamazepine, gabapentin, lamotrigine, oxcarbazepine, and topiramate in 1,721 patients, ages 5 years and up. The defined outcomes included the time from randomization to treatment failure (stopping the randomized drug because of inadequate seizure control, intolerable side effects, or both, or the addition of other antiepileptic drugs, whichever was earliest) and the time from randomization to 1-year remission of seizures. The study found that children under age 16 were more likely to experience treatment failure than adults. However, children were also more likely than adults to experience a 1-year remission of seizures. Notably, there was no evidence for any age-treatment interaction in the two defined outcomes (15). More studies, particularly RCTs, are needed to define possible age-treatment interactions, particularly the relative efficacies of AEDs according to age.

TABLE 1.

Issues for Neonates*

TABLE 2.

Issues for Children *

Issues Unrelated to Efficacy in AED Selection

Other specific issues, unrelated to efficacy, may lead to an age-related decision on selection of an AED. The ages of 18 to 50 include the prime childbearing years, and this must be taken into consideration. Among the newer AEDs, recent data indicate that the rate of fetal malformations is increased in children of women taking topiramate, and it has been designated as pregnancy category D by the FDA (16). Moreover, there is insufficient data to either rule in or out a risk of teratogenicity for a number of new AEDs (17, 18).

The need to control seizures also varies throughout the life span. Children with epilepsy are more likely to experience seizure remission than other age groups, suggesting that children should not be overtreated at the expense of adverse events. Nonetheless, experimental findings suggest that repeated seizures may have deleterious effects on brain development (18, 19). In adults, seizure control may need to be aggressively pursued for different reasons. Even a single seizure per year can impact the ability to drive and work, and subsequent independence. Furthermore, it is very important to control seizures in pregnant women. In the elderly, the urgency of the need to control seizures is often case dependent; sometimes other health conditions may take precedent over seizures.

Adherence to a drug regime can be problematic in patients with epilepsy, particularly in the adolescent and elderly age groups. It is not unusual for adolescents to forget to take their AEDs (or other medications) or to self-initiate trials off medication. Undesired adverse effects of AEDs may exacerbate compliance difficulties. Adolescent patients may also feel that taking an AED is stigmatizing or sets them apart from their peers. In the elderly, psychiatric disorders and burdensome medication costs often affect adherence to a drug regime. In fact, approximately half of all elderly patients exhibit poor adherence. In one study, phenobarbital, valproate, and gabapentin were associated with lower adherence in elderly patients, while lamotrigine and levetiracetam were associated with improved adherence (20). The cognitive side effects of phenobarbital, phenytoin, and levetiracetam may affect adherence in older patients. Improved adherence for lamotrigine and levetiracetam may be a result of the favorable side-effect profiles, which generally include fewer adverse effects than other AEDs.

Issues Related to Change in the Body Over Time

Changes in the body throughout the life span, which affect AED availability, include the rate of absorption, distribution, metabolism, and renal clearance. In neonates, drug absorption is variable, and metabolism is slower than it is in later childhood when it overtakes the rate seen in adults. Drug distribution in neonates is also variable, leading to the likelihood of a need for higher loading doses and lower-than-expected serum concentrations on a milligram per kilogram basis compared with older children. Protein binding is lower, leading to higher free fractions (21). By the age of 3 to 6 months old, clearance through metabolism speeds up and surpasses adult values. Thus, children and adolescents have faster metabolism and clearance than adults and require higher drug doses. Clearance slows towards adult values around the age of puberty. Stabilizing serum drug levels may be more difficult in young children than in older children and adults because of variability in absorption and drug metabolism, which if not addressed might increase the risk for breakthrough seizures and adverse events. Also of note, interactions between AEDs can differ in children as compared with adults. Information on these interactions can usually be found in the drug package insert.

In women who are in their childbearing years, other interaction issues should be considered. If pregnancy is contemplated, lamotrigine may be a concern. It is difficult to use in pregnancy, because clearance may rise markedly and serum concentrations must be followed carefully to prevent breakthrough seizures (22). In this age range, women are likely to be using birth control. Oral contraceptives may be rendered less effective by hepatic enzyme–inducing drugs such as carbamazepine, phenytoin, phenobarbital, and to a lesser extent topiramate and oxcarbazepine at higher doses. Other forms of hormonal contraception may also be problematic. Lamotrigine clearance is doubled by the oral contraceptive pill (23). This may guide selection of the most appropriate AED in women in this age group.

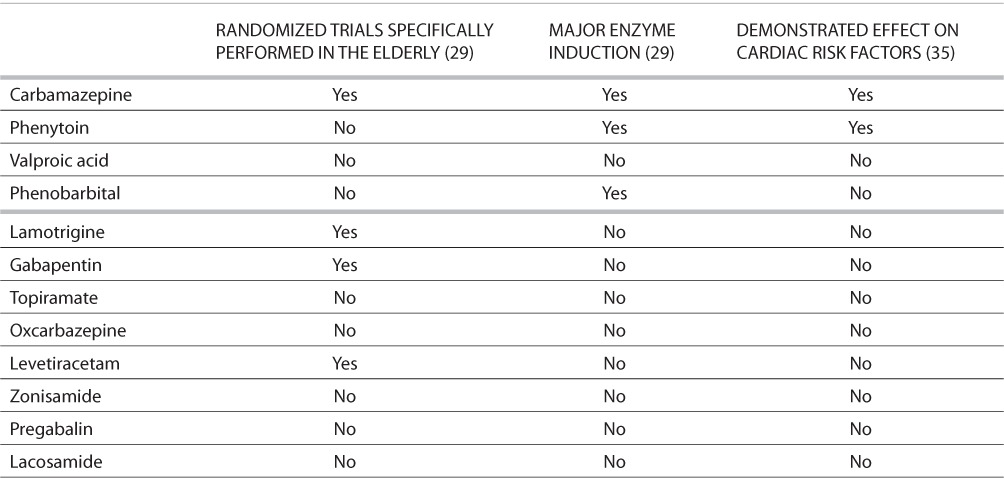

There are also special considerations related to absorption and metabolism in the elderly. Despite the fact that the incidence of epilepsy increases over the age of 65, regulatory trials typically do not include this age group. Fortunately, trials addressing pharmacokinetics are often done separately in this population. The elderly tend to have slower elimination of drugs (by 20–40%) owing to several factors, including slowed metabolic rate and reduction in renal clearance (24). Thus, the common wisdom of “start low and go slow” would be particularly prudent in this group. There is also an increasing variability with increasing age. This makes monitoring through AED levels more important. Other issues in the elderly include changes in unbound (free) drug for highly protein-bound compounds such as valproate and phenytoin, and marked increase in variability of absorption, particularly in nursing home patients (25–28). Elderly patients are also more likely than other age groups to be taking medications for other medical conditions and are subsequently at risk for adverse drug–drug interactions. Enzyme-inducing AEDs such as phenobarbital, phenytoin, and carbamazepine increase the metabolism of many commonly prescribed drugs. Enzyme induction can also affect endogenous substances like vitamin D and male sex hormones, which can cause problems such as osteoporosis or sexual dysfunction. Drugs that inhibit hepatic metabolic processes and subsequently increase circulating levels of AEDs and other drugs include sodium valproate, cimetidine, erythromycin, isoniazid, verapamil, and diltiazem. Carbamazepine and phenytoin use must be monitored carefully in patients with cardiac conduction issues (29).

Adverse Events at Different Ages

Some adverse effects of AEDs are more common in particular age groups. GABAergic agonists such as phenobarbital, and sodium channel blockers such as phenytoin, have been associated with widespread apoptosis of neurons in infant animal models (1), raising concern over their use in human infants. We don't know whether these effects also occur in the setting of seizures, and to what extent naturally occurring apoptosis is modified by other factors, ameliorating these effects. Some data suggest that AEDs that antagonize AMPA receptor-mediated ion channels, such as topiramate, may actually have a neuroprotective and anticonvulsant effect (30).

In general, infants and children are more susceptible to some adverse drug effects than adults, whereas they can be more tolerant of others. Children are particularly more likely to experience the cosmetic effects of phenytoin than adults, including hirsutism and gingival hyperplasia, and less commonly, coarsening of facies (31). Children are also at higher risk of developing Stevens-Johnson syndrome from lamotrigine, as well as hepatic injuries from the use of valproate in combination with enzyme-inducing AEDs. Yet, they are relatively resistant to the aplastic anemia caused by felbamate (30). Vigabatrin appears to adversely affect adults more often than children. Visual field defect has been reported in 30% of adults receiving vigabatrin, in 19% of older children, and 2% in infants and young children treated for infantile spasms (32). Behavioral and cognitive side effects of AEDs can be initially difficult to distinguish from newly emergent psychiatric and neurocognitive disorders in children (31) and adolescents, yet they are important to differentiate because the therapeutic approaches differ.

It is particularly important to consider potential adverse effects of AEDs in adolescents. Adolescence is a vital period for the development of self-esteem and socialization. Some adolescents may be sensitive to adverse drug effects that alter the appearance. These include weight gain associated with valproate, weight loss associated with topiramate and felbamate, the cosmetic effects of phenytoin, and hair loss seen in patients with valproate, carbamazepine, and rarely clonazepam. Some AEDs, such as phenobarbital, may aggravate preexisting behavioral or attention disorders, which can interfere with socialization and focus in school. Clinicians should try to achieve a suitable balance between seizure control and side effects in adolescent patients (33).

Elderly patients are at higher risk for adverse effect of AEDs than younger adults, and these effects often occur at lower doses than in younger adults. This is particularly true of side effects such as sedation, balance disturbance, and cognitive disturbance. Cognitive and behavioral side effects of AEDs may exacerbate or uncover underlying disorders, such as of dementia and Alzheimer disease in the elderly population. They may also exacerbate underlying gait disorders, increasing the risk of falls.

Some adverse effects of AEDs pertain to women exclusively, and these are only relevant during the child-bearing years, including pregnancy and breast-feeding. Some AEDs, such as valproate, carbamazepine, and topiramate, are associated with congenital malformations in offspring (17). Lamotrigine is considered to be a safer drug in this respect, although increased risk of cleft palate has been reported. Polytherapy also places women at increased risk for birth defects in offspring. AED exposure from breast-feeding could result in adverse cognitive and behavioral symptoms in children. Some AEDs, such as the enzyme-inducing AEDs, are transferred to breast milk in low levels, while others, such as levetiracetam and primidone, are transferred at higher levels (34).

AED selection may be influenced by the route of drug administration. Lack of appropriate drug formulations may limit use of certain antiepileptic drugs in the very young and the very old. For example, most neonatal seizures are treated with intravenous medication because of the severity of associated disorders and the prolonged nature of many neonatal seizures. Very young children will not be able to swallow pills, and AED choice is often limited to those with a liquid formulation. Elderly patients in nursing homes may require administration of drugs through a nasogastric tube, which would eliminate some formulations, including most delayed-release formulations. Issues related to availability of formulations in neonates, children, and the elderly can be found in Tables 1–3.

TABLE 3.

Issues for the Elderly*

Thus over the life span there are substantial differences in seizure etiology, the prevalence of seizure types, the prevalence and acceptability of particular side effects, and the bioavailability of AEDs. The impact of these differences on AED efficacy and compliance clearly requires further study. In the meantime, we must carefully weigh these age-related issues in coming to a decision as to which AED is best for each individual patient.

Acknowledgments

As Director of the Epilepsy Study Consortium (ESC), Dr. French consults for a number of companies, on behalf of ESC, and takes no personal income. Dr French is paid 20% of her academic salary for all work performed for ESC. Companies involved have included Glaxo-Smith Kline, Pfizer, UCB Pharma, Johnson and Johnson, Cyberonics, Schwarz Pharma, Ortho-McNeil, Eisai, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Ovation Pharmaceuticals, Endo Pharmaceuticals, Bial Pharmaceuticals, Neurovista, Valeant Pharmaceuticals, Icagen, Supernus, Ikano, SK Pharmaceuticals, Taro Pharmaceuticals, Neurotherapeutics, Sepracor, Novartis, Vertex, and Upsher-Smith.

References

- 1.Ikonomidou C, Turski L. Antiepileptic drugs and brain development. Epilepsy Res. 2010;88:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2009.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jensen FE. Developmental factors in the pathogenesis of neonatal seizures. J Pediatr Neurol. 2009;7:5–12. doi: 10.3233/JPN-2009-0270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carmo KB, Barr P. Drug treatment of neonatal seizures by neonatologists and paediatric neurologists. J Paediatr Child Health. 2005;41:313–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2005.00638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Painter MJ, Scher MS, Stein AD. Phenobarbital compared with phenytoin for the treatment of neonatal seizures. New Engl J Med. 1999;341:485–489. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908123410704. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silverstein FS, Ferriero DM. Off-label use of antiepileptic drugs for the treatment of neonatal seizures. Pediatr Neurol. 2008;39:77–79. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fogarasi A, Tuxhorn I, Janszky J. Age-dependent seizure semiology in temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2007;48:1697–1702. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01129.x. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palop JJ, Mucke L. Epilepsy and cognitive impairments in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:435–440. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olafsson E, Ludvigsson P, Gudmundsson G, Hesdorffer D, Kjartansson O, Hauser WA. Incidence of unprovoked seizures and epilepsy in Iceland and assessment of the epilepsy syndrome classification: A prospective study. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4:627–634. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70172-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holmes GL, Khazipov R, Ben-Ari Y. New concepts in neonatal seizures. Neuroreport. 2002;13:A3–8. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200201210-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leppik IE, Kelly KM, deToledo-Morrell L. Basic research in epilepsy and aging. Epilepsy Res. 2006;68(suppl):S21–S37. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2005.07.014. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hancock E, Osborne JP. Vigabatrin in the treatment of infantile spasms in tuberous sclerosis: Literature review. J Child Neurol. 1999;14:71–74. doi: 10.1177/088307389901400201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.French JA, Kanner AM, Bautista J. Efficacy and tolerability of the new antiepileptic drugs II: Treatment of refractory epilepsy. Report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee and Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Epilepsy Society. Neurology. 2004;62:1261–1273. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000123695.22623.32. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.French JA, Kanner AM, Bautista J. Efficacy and tolerability of the new antiepileptic drugs I: Treatment of new onset epilepsy. Report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee and Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Epilepsy Society. Neurology. 2004;62:1252–1260. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000123693.82339.fc. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.European Medicines Agency. Guideline on clinical investigation of medicinal products in the treatment of epileptic disorders. EMA Web site. http://www.ema.europa.eu/pdfs/human/ewp/056698enrev2.pdf. Accessed Month day, year. [PubMed]

- 15.Marson AG, Al-Kharusi AM, Alwaidh M. The SANAD study of effectiveness of carbamazepine, gabapentin, lamotrigine, oxcarbazepine, or topiramate for treatment of partial epilepsy: An unblinded randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;369:1000–1015. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60460-7. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hunt S, Russell A, Smithson WH. Topiramate in pregnancy: Preliminary experience from the UK Epilepsy and Pregnancy Register. Neurology. 2008;71:272–276. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000318293.28278.33. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tomson T, Battino D. Teratogenic effects of antiepileptic medications. Neurol Clin. 2009;27:993–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cornejo BJ, Mesches MH, Coultrap S, Browning MD, Benke TA. A single episode of neonatal seizures permanently alters glutamatergic synapses. Ann Neurol. 2007;61:411–426. doi: 10.1002/ana.21071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holmes GL, Ben-Ari Y. Seizures in the developing brain: Perhaps not so benign after all. Neuron. 1998;21:1231–1234. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80642-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zeber JE, Copeland LA, Pugh MJ. Variation in antiepileptic drug adherence among older patients with new-onset epilepsy. Annals Pharmacother. 2010;44:1896–1904. doi: 10.1345/aph.1P385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gilman JT, Duchowny M, Campo AE. Pharmacokinetic considerations in the treatment of childhood epilepsy. Paediatr Drugs. 2003;5:267–277. doi: 10.2165/00128072-200305040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pennell PB, Peng L, Newport DJ. Lamotrigine in pregnancy: Clearance, therapeutic drug monitoring, and seizure frequency. Neurology. 2008;70:2130–2136. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000289511.20864.2a. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harden CL, Pennell PB, Koppel BS. Practice parameter update: Management issues for women with epilepsy—focus on pregnancy (an evidence-based review): Vitamin K, folic acid, blood levels, and breastfeeding. Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee and Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and American Epilepsy Society. Neurology. 2009;73:142–149. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181a6b325. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perucca E, Berlowitz D, Birnbaum A. Pharmacological and clinical aspects of antiepileptic drug use in the elderly. Epilepsy Res. 2006;68(suppl):S49–S63. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2005.07.017. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perucca E, Grimaldi R, Gatti G, Pirracchio S, Crema F, Frigo GM. Pharmacokinetics of valproic acid in the elderly. British J Clin Pharm. 1984;17:665–669. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1984.tb02401.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perucca E. Plasma protein binding of phenytoin in health and disease: Relevance to therapeutic drug monitoring. Ther Drug Monit. 1980;2:331–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Birnbaum AK, Ahn JE, Brundage RC, Hardie NA, Conway JM, Leppik IE. Population pharmacokinetics of valproic acid concentrations in elderly nursing home residents. Ther Drug Monit. 2007;29:571–575. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0b013e31811f3296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Birnbaum A, Hardie NA, Leppik IE. Variability of total phenytoin serum concentrations within elderly nursing home residents. Neurology. 2003;60:555–559. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000052997.43492.e0. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brodie MJ, Elder AT, Kwan P. Epilepsy in later life. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:1019–1030. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70240-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pellock JM. Felbamate. Epilepsia. 1999;40(suppl):S57–S62. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1999.tb00920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sankar R. Initial treatment of epilepsy with antiepileptic drugs: Pediatric issues. Neurology. 2004;63:S30–S39. doi: 10.1212/wnl.63.10_suppl_4.s30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Camposano SE, Major P, Halpern E, Thiele EA. Vigabatrin in the treatment of childhood epilepsy: A retrospective chart review of efficacy and safety profile. Epilepsia. 2008;49:1186–1191. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nordli DR., Jr. Special needs of the adolescent with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2001;42(suppl):10–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klein A. Antiepileptic drugs and breastfeeding: Do we tell women “no”? Neurology. 2010;75:1948–1949. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181ff94d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mintzer S, Skidmore CT, Abidin CJ. Effects of antiepileptic drugs on lipids, homocysteine, and C-reactive protein. Ann Neurol. 2009;65:448–456. doi: 10.1002/ana.21615. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]