Abstract

The limitations of allogeneic transplantation are graft-versus-host disease (both acute and chronic), infection, and relapse. Acute GVHD has traditionally been thought of as a Th1-mediated disease with inflammatory cytokines (eg, inteferon [IFN]-γ and tumor necrosis factor [TNF]) and cellular cytolysis mediating apoptotic target tissue damage in skin, gut, and liver. Chronic GVHD has not fit neatly into either Th1 or Th2 (eg, IL-4, IL-13) paradigms. Increasingly, the Th17 pathway of differentiation has been shown to play important roles in acute and chronic GVHD (aGVHD, cGVHD), particularly in relation to skin and lung disease. Here we discuss the IL-17 pathway of T cell differentiation and the accumulating evidence suggesting it represents an important new target for the control of deleterious alloimmune responses.

Keywords: Bone marrow transplantation, Graft-versus-host disease, Cytokines

INTRODUCTION

There have been a number of inconsistencies in the traditional Th1/Th2 paradigm, many of which have been explained by the description of regulatory T cell and Th17 differentiation pathways. Interleukin (IL)-17 can be produced by most cells (including non-immune cells such as epithelia [1]), although its generation by CD4+ T cells is the most widely studied. The IL-17 family includes 6 members from A to F, the main isoforms studied being IL-17A and IL-17F [2]. IL-17 usually refers to IL-17A, which is the most potent form, and together with IL-17A/F heterotrimers reflects the major biologically active cytokine (reviewed in Shen and Geffen [3]). More recently, IL-25 (IL-17E) has been shown to play important roles in promoting Th2 responses in allergic and parasitic diseases where it is produced by CD4 T cells and epithelial cells (reviewed in Paul and Zhu [4]). IL-17A function is mediated via the IL-17R, which comprises the A and C subunits, and appears ubiquitously expressed on both hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic tissues [5].

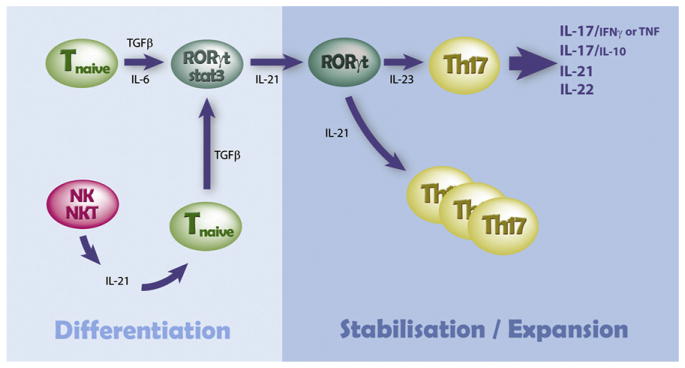

Generation of Th17 cells is dependent on the transcription factors RORγt, RORα, IRF4, and STAT3. Th17 cells generate pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-17A, IL-17F, IL-21, IL-22, tumor necrosis factor (TNF), granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF), and the chemokines CXCL1, CXCL2, and CXCL8. Th17 cells express CCR6 and CCL20 and are particularly recruited to sites of inflammation via this chemokine receptor. IL-17A acts predominantly as a chemo attractant to different cell types via the induction of cytokines (eg, GM-CSF, granulocyte-colony stimulating factor [G-CSF], and chemokines [2]. As outlined in Figure 1, transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 is central to Th17 differentiation from naive T cells, usually in combination with IL-6. Both TGF-β1 and IL-6 can be produced by almost any cell type, but myeloid hematopoietic cells (eg, monocytes, macrophages) have an enhanced potential during inflammatory states. Th17 differentiation can also occur independently of IL-6, if TGF-β is present in combination with high concentrations of IL-21 (from natural killer or natural killer T cells). Stabilization and maintenance of the Th17 phenotype subsequently requires IL-23 (produced predominantly by antigen presenting cells), with support from TNF and IL-1β, while expansion is dependent on IL-21 (produced predominantly by activated T cells, natural killer cells, and natural killer T cells).

Figure 1.

Schematic of the cytokine-dependent control of Th17 differentiation. Adapted from Bettelli et al [53].

The RORγt transcription factor is central to Th17 differentiation, in a similar fashion to T-bet for Th1 and GATA-3 for Th2 differentiation. Interestingly, TGF-β in the absence of IL-6 or high concentrations of IL-21 instead drives regulatory T cell differentiation, where Foxp3 is the critical transcription factor. Both Th1 and Th2 cells inhibit Th17 differentiation, via IFN-γ and IL-4, respectively [1]. Th-17 cells promote pathogenic immune-mediated organ damage in conditions targeting brain (multiple sclerosis), arthritis (rheumatoid arthritis), colitis (inflammatory bowel disease), allergic skin (psoriasis), and lung (transplant rejection; reviewed in Steinman [1]). However, it is now clear that Th-17 cells may have pathogenic or regulatory effects, depending on the coproduction of proinflammatory (TNF and IFN-γ) or anti-inflammatory (IL-10 and IL-22) cytokines [6,7]. Whether protective or pathogenic Th-17 cells are generated may be dependent on the presence or absence of continued IL-6 signaling during phenotype stabilization by IL-23 [6].

IL-17 and Acute Graft-versus-Host Disease (aGVHD)

It has been established for over 40 years that T cells are critically required for the generation of the inflammatory response termed aGVHD[8–10]. Interestingly, although a critical role for T cells in the pathology of aGVHD is clear, which of the specific subsets of T cells is critical for the pathology that mediates aGVHD is less clear. Th1 cytokines can be found in lesional tissue from patients with aGVHD, which has led investigators to surmise that aGVHD is a Th1-mediated process [11,12]. However, neither IFN-γ nor the transcription factor T-bet is required to generate GVHD in animal models [13–15]. This has suggested that other T cell lineages could potentially mediate aGVHD.

Can Th17 cells mediate pathology associated with aGVHD? The answer to this query is certainly yes. Our group used a novel approach to generate a highly homogenous population of donor Th17 cells ex vivo. When we infused these T cells into lethally irradiated haploidentical, minor or major histocompatibility complex mismatched recipient mice, we found substantial pathology in GVHD target organs [16]. The pathology was particularly striking in the skin and lung and much greater than that found using naive T cells. However, all GVHD target organs were affected by Th17 cells with gastrointestinal (GI) tract and liver pathology being similar to that induced by naive T cells.

Are Th17 cells involved in the pathology associated with aGVHD? This question has been somewhat harder to discern. In general, investigators have attempted to address this by using genetic approaches or pharmacologic inhibitors of cytokines critical for the generation, expansion, or effector function of Th17 cells, or blocking the activity of transcription factors important for Th17 generation in preclinical models. These approaches have yielded conflicting information, which in some instances may relate to the myriad of activities of proteins important for the generation of Th17 cells. For instance, 2 different groups evaluated the role of IL-17A in the pathology of aGVHD with 1 showing a modest decrease in aGVHD when donor T cells could not generate IL-17A, whereas the second group showed increased pathology in recipient mice given donor T cells unable to generate IL-17A [17,18]. Interestingly, these discordant data were generated using the same models and strain of mice. Subsequently, a report confirmed a modest pathogenic contribution of IL-17A to aGVHD in multiple major histocompability complexes matched and minor mismatched models of bone marrow transplantation (BMT) that was most dominant in the skin [19]. Multiple different groups have shown that the absence of IL-21 or the IL-21 receptor inhibits aGVHD (and graft-versus-leukemia), although the mechanisms for this differed and included an increase in inducible regulatory T cells, an increase in natural regulatory T cells, or diminished effector T cell function in lymphoid tissue draining the GI tract [19–23]. Clearly, targeting TNF diminishes aGVHD, although the contribution that Th17 cells make to the generation of this cytokine is not clear [24].

A second approach to evaluate the function of Th17 cells is to block transcription factors critical to their generation such as RORγt, RORα, and/or IRF-4. Our group and another have evaluated whether T cells require the expression of RORC(generates 2 isoforms including RORγt). The initial data indicated that the absence of RORC in a model of GVHD mediated solely by CD4+ T cells did not impact on the incidence or severity of aGVHD [25]. This group did find that the absence of both TBOX21 (T-bet) and RORC diminished aGVHD. Our group confirmed these data but also found that, in models in which both CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells are critical to the induction of GVHD pathology, the absence of RORC in CD4+ T cells greatly diminished aGVHD. This was associated with diminished generation of IL-17A and TNF in serum and GVHD target organs (Fulton and Serody, submitted).

Similarly, a number of studies have investigated the function of the cytokines that generate Th17 cells, particularly IL-6 and IL-23, in the pathogenesis of aGVHD. Here, the data are more straightforward, although the roles that Th17 cells play in these data are not as clear. The absence of IL-6 in donor T cells and the inhibition of IL-6R with antibody neutralization significantly diminished aGVHD without overtly effecting GVL [26,27]. This was associated with diminished generation of Th1 and Th17 cells in GVHD target organs and the spleen with enhanced regulatory T cell generation in 1 study [26]. The second study, while confirming the potent protective effect of IL-6 inhibition, found this to be independent of effects on T cell differentiation [27]. Similarly, using genetic or pharmacologic approaches, blocking the function of IL-23 was found to diminish aGVHD without affecting the antitumor property of donor T cells critical for the success of allogeneic transplantation [28–30]. This was associated in 1 study with diminished IFN-γ generation in the GI tract of recipient animals and in another study with diminished IL-17A. At this time, a role for IL-22 in the pathogenesis of aGVHD is not clear, although our group has evidence that this cytokine may be critically important to the pathology induced by donor T cells (Ott and Serody, unpublished).

Are Th17 cells critical for pathology found in patients with aGVHD? Again, this straightforward question has been somewhat difficult to determine. A previous study found that the frequency of Th17 cells in the peripheral blood was increased in patients with aGVHD compared with healthy donors or allograft recipients without GVHD [31]. This correlated with increased levels of IL-17 in the plasma, but only in patients with active GVHD, compared with recipients without GVHD or healthy donors. Interestingly, they found that patients with active GVHD had a decreased percentage of Foxp3-expressing regulatory T cells, and that in a very small subset of patients the decrease in this population correlated with increases in the frequency of Th17 cells. They evaluated for the presence of T cells in the skin from 6 patients and found that all of the CD3+T cells were generating IL-17 and IFN-γ, which was similar to the cytokine expression from T cells isolated from the liver. Although it is hard to draw firm conclusions from anecdotal longitudinal assessments, this group used IL-17 ELISPOT assays to demonstrate that increases in this cell population correlated with the occurrence of aGVHD.

However, 2 other groups have not been able to correlate a specific role for Th17 cells in skin or GI tract GVHD [32,33]. For both of these evaluations, the presence of IL-17A was evaluated with the first group using ex vivo stimulated T cells and the second using immunohistochemistry. Neither demonstrated the presence of T cells expressing IL-17A from the skin. Additionally, the presence of IL-17A in the GI tract was evaluated and also not found. However, it should be noted that there are major limitations in the ability to draw any conclusions in relation to cause and effect from these clinical studies. For instance, 1 of these studies found that increased numbers of regulatory T cells in tissue correlated with GVHD [33]. Furthermore, it is not clear that alloreactive Th17 cells will maintain this phenotype in culture over 3 weeks in the absence of polarizing cytokines, which were not added in 1 study [32].

A second approach to evaluating the role of the Th17 axis has involved analysis for single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with GVHD in IL-23 or the IL-23 receptor (IL-23R). Previous work had shown a very strong association between an SNP present in the IL-23R (G to A change at 1142 leading to a substitution of glycine for arginine, R381G, and Crohn’s disease. This SNP is located in the IL-23 receptor chain of the IL-23 receptor. A group in Germany evaluated the G>A change in a cohort of 221 transplant recipients and their HLA identical donors [34]. The gene variant occurred in 13.1% of recipients and 11.3% of donors. Severe grade III-IV aGVHD was found less frequently in recipients transplanted with donor cells with the IL-23R SNP (22% versus 4%). In this evaluation, all but 1 donor and recipient were heterozygous for the SNP. A second cohort undergoing unrelated transplantation was also evaluated in which all donors and recipients who had the SNP were heterozygous. Again, recipients transplanted with donors having the IL-23R SNP had a significant decrease in grade III-IV aGVHD compared with those receiving donor cells with the wild-type SNP (3.8% versus 25.5%). However, in this analysis there was no beneficial effect if only the recipients had the IL-23R G>A change. Overall survival was not impacted by the presence of the IL-23R polymorphism.

Two other groups have evaluated the interaction between polymorphisms in the IL-23R and outcome posttransplantation, with 1 group focusing on children and young adults [35]. The IL-23R SNP was found in 7.8% of patients and 11% of donors with, again, none of the patients being homozygous for this. Patients receiving donor grafts with the G>A SNP had a significantly decreased risk of aGVHD (5% versus 33.3% for grade II or greater); however, in this analysis unlike in the previous analysis, the frequency of severe GVHD was not affected by the occurrence of the polymorphism in the patient. When this group confined their analysis only to patients under the age of 16, there was still a statistically significant decreased incidence of aGVHD when the donor had the G>A polymorphism in the IL-23R. Again, no association with the G>A polymorphism and the incidence of chronic GVHD (cGVHD) or overall survival was found.

However, 1 recent paper has questioned whether the G>A polymorphism in the IL-23R is implicated in a diminished risk of aGVHD [36]. A total of 390 patients who underwent T-replete transplants for the treatment of acute or chronic leukemia or myelodysplastic syndrome using primarily myeloablative conditioning were included. Two SNPs in the IL-23R, including the G>A SNP, and a second polymorphism associated with ankylosing spondylitis were evaluated. A total of 13% of the donors and 16% of the recipients had the variant SNPs. No association between either of the SNPs and the incidence or severity of aGVHD was found. Thus, it is not clear at this time if these differences are because of differences in the (1) transplantation approaches, (2) methods used to prevent GVHD, or (3) perhaps ethnic differences in the activity of the IL-23 axis between these cohorts.

Finally, it is now clear that our perceived understanding of the lineage fidelity of T cells needs to be altered. Our group and a number of others has found that Th17 cells rapidly undergo epigenetic modifications in the presence of IL-12, which mediates the loss of expression of IL-17A, and IL-17F and the increased expression of IFN-γ. We have found that a substantial number of IFN-γ producing T cells in recipient mice after transplantation come from a population of donor T cells that were initially skewed to a Th17 lineage, but later posttransplantation are indistinguishable from Th1 cells (Carlson, Ott, and Serody, unpublished). Thus, early Th17 T cell polarization may not be identified when tissue biopsies are performed at the time of GVHD involvement. If this is true clinically, it would suggest that aGVHD might best be termed a Th1/Th17 process.

IL-17 and cGVHD

Chronic GVHD is the major cause of late nonrelapse death following stem cell transplantation (SCT). Its presentation may be progressive (active or aGVHD merging into chronic), or de novo (occurring without prior aGVHD). Older recipient age and a history of aGVHD are the greatest risk factors for cGVHD [37], and strategies to prevent aGVHD may help to prevent cGVHD. However, scleroderma, the primary manifestation of cGVHD, can also develop in a de novo fashion, late after BMT in the absence of prior clinical aGVHD. It is also noteworthy that cGVHD develops with high frequency in recipients of T cell–depleted transplants, suggesting that non–T cell pathways exist, or alternatively, that bone marrow–derived and pathogenic autoreactive T cell development occurs [38]. The majority of clinical transplants are currently undertaken using G-CSF mobilized peripheral blood stem cells, and it is now clear that cGVHD is significantly enhanced in this setting [39]. Importantly, unlike aGVHD, effective therapy options are very limited for cGVHD.

In contrast to aGVHD, the pathophysiology of cGVHD still remains poorly defined. Chronic GVHD manifests with features characteristic of autoimmune disease, including sclerodermatous skin disease, and does not fit easily into either Th1 or Th2 paradigms [12,40], although IFN-γ can clearly play a causal role [32,41]. Recently, the Th17 pathway of T cell differentiation has been demonstrated to promote pathogenic autoimmune-mediated organ damage in conditions such as multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, and psoriasis [1]. Notably, in systemic sclerosis, a condition closely resembling scleroderma, the predominant clinical feature of cGVHD after SCT, fibrosis is mediated by Th17 cells infiltrating the skin and serum IL-17 levels positively correlate with disease severity [42,43]. In preclinical studies where true cause and effect can be delineated, most publications demonstrate pathogenic effects of donor-derived IL-17A on GVHD, particularly in skin and lung [16,19]. However, as a whole, these effects are limited early after BMT, consistent with the established notion that the dominant aspects of aGVHD, particularly that found in the GI tract are most associated with a Th1 process [39]. In the setting of cGVHD, recent preclinical and clinical data support a role for IL-17A as a central mediator of pathology, particularly within the skin [16,19,31]. We have demonstrated that G-CSF promotes type-17 differentiation within both conventional CD4+ and CD8+ populations, and that this effect is downstream of IL-21. Importantly, the majority of IL-17A generated late after BMT when scleroderma manifests in these systems is from CD8+ T cells and the disease process was confirmed to be CD8-dependent. How IL-17A induces scleroderma remains unclear, but is likely to be because of the control of the cellular migration of fibrogenic populations, particularly granulocytes and monocytes/ macrophages [19] and perhaps T cells.

FoxP3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) are critical for the maintenance of peripheral tolerance, and disruption of the development or function of Tregs leads to development of autoimmune disease [44]. Equally, Tregs are crucial for the establishment and maintenance of tolerance after SCT. Notably, Treg populations are diminished in the clinical setting of aGVHD and cGVHD [45–47]; however, the factors that contribute to their absence and the mechanism by which their absence results in pathology is not entirely clear. The fact that these cells are thymic dependent and that this organ is a target of GVHD, together with impairment of peripheral T cell homeostasis, are likely to be important. In addition, the requirement of the highly fibrogenic cytokine TGF-β [48] in the expansion and homeostasis of both Treg and IL-17 differentiation suggests a “ying and yang” type pathogenic versus protective relationship between IL-17 and Tregs differentiation in cGVHD.

Importantly, clinical studies that have linked IL-17A to aGVHD have shown concurrent links to Th1 cytokines [31,49]. What is clear both preclinically [17,19] and clinically [31] is that during aGVHD, IL-17A producing cells can also coproduce IFN-γ, making attempts to correlate disease with the generation of IL-17A alone very difficult. In contrast to the posttransplantation setting, IL-17A and IFN-γ generation are generated independently by T cells from healthy donors [19], and so in theory, the induction of a single cytokine may be informative. We have shown that G-CSF administration promotes the induction of type 17 cells [2], and Sun et al. [50] confirmed this in healthy donors. A subsequent study demonstrated a reduction in the proportion of IL-17A producing cells within the CD4 compartment during G-CSF administration; however, this work also demonstrated an induction of IL-17A producing and RORγt expressing T cells following G-CSF [51]. Importantly, stem cell mobilization with G-CSF results in an increase in the total numbers of CD3+ T cells in peripheral blood, and we have noted that the numbers of CD8+IL-17+ T cells (but not any IFN-γ+ T cell subset) are significantly increased (unpublished data).

Thus, although there is little doubt IL-17A can contribute to GVHD, effects early after BMT are somewhat modest in our hands (and others [8,50]) and IL-17A generation is augmented by the use of G-CSF mobilized grafts. Although the pathogenic effects of IL-17A on cutaneous and particularly cGVHD are clear [19,31], they are still difficult to interpret independently of coexpressed Th1 cytokines with current technology. It is also clear that Th17 cells generate a number of important cytokines (IL-21, IL-22, TNF, GM-CSF, IL-17F) that may be critical to the pathogenesis of aGVHD and/or cGVHD. Thus, the absence of an effect by targeting IL-17A alone does not indicate the absence of a role for Th17 cells. Additionally, given the plasticity of the Th17 lineage and the ability of those cells to convert to conventional Th1 cells, it is likely that both Th1 and Th17 pathways contribute to aGVHD and/or cGVHD. How these differentiation pathways interact to cause disease will likely be an important issue for the development of rational therapy. In the future, armed with this information, the field will need to progress to well-designed prospective clinical studies using active clinical grade IL-17 inhibitors currently in early phase trials in inflammatory diseases such as psoriasis. It will be critical to base these studies on informative preclinical studies that demonstrate when and how IL-17A [17–19], similar to IFN-γ [13,52], might mediate protective versus pathogenic effects after BMT.

Footnotes

Financial disclosure: The authors did not supply any financial disclosure.

References

- 1.Steinman L. A brief history of T(H)17, the first major revision in the T(H)1/T(H)2 hypothesis of T cell-mediated tissue damage. Nat Med. 2007;13:139–145. doi: 10.1038/nm1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kolls JK, Linden A. Interleukin-17 family members and inflammation. Immunity. 2004;21:467–476. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shen F, Gaffen SL. Structure-function relationships in the IL-17 receptor: implications for signal transduction and therapy. Cytokine. 2008;41:92–104. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2007.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paul WE, Zhu J. How are T(H)2-type immune responses initiated and amplified? Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:225–235. doi: 10.1038/nri2735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yao Z, Fanslow WC, Seldin MF, et al. Herpesvirus Saimiri encodes a new cytokine, IL-17, which binds to a novel cytokine receptor. Immunity. 1995;3:811–821. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kleinschek MA, Owyang AM, Joyce-Shaikh B, et al. IL-25 regulates Th17 function in autoimmune inflammation. J Exp Med. 2007;204:161–170. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGeachy MJ, Bak-Jensen KS, Chen Y, et al. TGF-beta and IL-6 drive the production of IL-17 and IL-10 by T cells and restrain T(H)-17 cell-mediated pathology. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1390–1397. doi: 10.1038/ni1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Billingham RE. The biology of graft-versus-host reactions. Harvey Lec. 1966;62:21–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blaese RM, Martinez C, Good RA. Immunologic incompetence of immunologically runted animals. J Exp Med. 1964;119:211–224. doi: 10.1084/jem.119.2.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dausset J, Colombani J, Legrand L, Feingold N, Rapaport FT. Genetic and biological aspects of the HL-A system of human histocompatibility. Blood. 1970;35:591–612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krenger W, Ferrara JLM. Graft-versus-host disease and the Th1/Th2 paradigm. Immunol Res. 1996;15:50–73. doi: 10.1007/BF02918284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morris ES, Hill GR. Advances in the understanding of acute graft-versus-host disease. Br J Haematol. 2007;137:3–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burman AC, Banovic T, Kuns RD, et al. IFNgamma differentially controls the development of idiopathic pneumonia syndrome and GVHD of the gastrointestinal tract. Blood. 2007;110:1064–1072. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-063982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murphy WJ, Welniak LA, Taub DD, et al. Differential effects of the absence of interferon-gamma and IL-4 in acute graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation in mice. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:1742–1748. doi: 10.1172/JCI3906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu Y, Wang D, Liu C, et al. Prevention of GVHD while sparing GVL by targeting Th1 and Th17 transcription factor T-bet and ROR{gamma}t in mice. Blood. Sep 2; doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-340315. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carlson MJ, West ML, Coghill JM, et al. In vitro-differentiated TH17 cells mediate lethal acute graft-versus-host disease with severe cutaneous and pulmonary pathologic manifestations. Blood. 2009;113:1365–1374. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-162420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kappel LW, Goldberg GL, King CG, et al. IL-17 contributes to CD4-mediated graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2009;113:945–952. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-08-172155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yi T, Zhao D, Lin C-L, et al. Absence of donor Th17 leads to augmented Th1 differentiation and exacerbated acute graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2008;112:2101–2110. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-126987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hill GR, Olver SD, Kuns RD, et al. Stem cell mobilization with G-CSF induces type 17 differentiation and promotes scleroderma. Blood. 2010;116:819–828. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-256495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meguro A, Ozaki K, Oh I, et al. IL-21 is critical for GVHD in a mouse model. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2010;45:723–729. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2009.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meguro A, Ozaki K, Hatranaka K, et al. Lack of IL-21 signal attenuates graft-versus-leukemia effect in the absence of CD8 T-cells. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2011 doi: 10.1038/bmt.2010.342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bucher C, Koch L, Vogtenhuber C, et al. IL-21 blockade reduces graft-versus-host disease mortality by supporting inducible T regulatory cell generation. Blood. 2009;114:5375–5384. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-221135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanash AM, Kappel LW, Yim NL, et al. Abrogation of donor T-cell IL-21 signaling leads to tissue-specific modulation of immunity and separation of GVHD from GVL. Blood. 2011;118:446–455. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-294785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hill GR, Crawford JM, Cooke KR, et al. Total body irradiation and acute graft-versus-host disease: the role of gastrointestinal damage and inflammatory cytokines. Blood. 1997;90:3204–3213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iclozan C, Yu Y, Liu C, et al. T helper17 cells are sufficient but not necessary to induce acute graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16:170–178. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen X, Das R, Komorowski R, et al. Blockade of interleukin-6 signaling augments regulatory T-cell reconstitution and attenuates the severity of graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2009;114:891–900. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-01-197178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tawara I, Koyama M, Liu C, et al. Interleukin-6 modulates graft-versus-host responses after experimental allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:77–88. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Das R, Chen X, Komorowski R, Hessner MJ, Drobyski WR. Interleukin-23 secretion by donor antigen-presenting cells is critical for organ-specific pathology in graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2009;113:2352–2362. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-08-175448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thompson JS, Chu Y, Glass JF, Brown SA. Absence of IL-23p19 in donor allogeneic cells reduces mortality from acute GVHD. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2010;45:712–722. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2009.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Das R, Komorowski R, Heessner MJ, et al. Blockade of interleukin-23 signaling results in targeted protection of the colon and allows for separation of graft-versus-host and graft-versus-leukemia responses. Blood. 2010;115:5249–5258. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-255422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dander E, Balduzzi A, Zappa G, et al. Interleukin-17-producing T-helper cells as new potential player mediating graft-versus-host disease in patients undergoing allogeneic stem-cell transplantation. Transplantation. 2009;88:1261–1272. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181bc267e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Broady R, Yu J, Chow V, et al. Cutaneous GVHD is associated with the expansion of tissue-localized Th1 and not Th17 cells. Blood. 2010;116:5748–5751. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-295436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ratajczak P, Janin A, Peffault de Latour R, et al. Th17/Treg ratio in human graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2010;116:1165–1171. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-255810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elmaagacli AH, Koldehoff M, Landt O, Beelen DW. Relation of an interleukin-23 receptor gene polymorphism to graft-versus-host disease after hematopoietic-cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2008;41:821–826. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gruhn B, Intek J, Pfaffendorf N, et al. Polymorphism of interleukin-23 receptor gene but not of NOD2/CARD15 is associated with graft-versus-host disease after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in children. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15:1571–1577. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nguyen Y, Al-Lehibi A, Gorbe E, et al. Insufficient evidence for association of NOD2/CARD15 or other inflammatory bowel disease-associated markers on GVHD incidence or other adverse outcomes in T-replete, unrelated donor transplantation. Blood. 2010;115:3625–3631. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-09-243840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carlens S, Ringdén O, Remberger M, et al. Risk factors for chronic graft-versus-host disease after bone marrow transplantation: a retrospective single centre analysis. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1998;22:755–761. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1701423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Champlin RE, Schmitz N, Horowitz MM, et al. Blood stem cells compared with bone marrow as a source of hematopoietic cells for allogeneic transplantation. IBMTR Histocompatibility and Stem Cell Sources Working Committee and the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) Blood. 2000;95:3702–3709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morris ES, MacDonald KP, Hill GR. Stem cell mobilization with G-CSF analogs: a rational approach to separate GVHD and GVL? Blood. 2006;107:3430–3435. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ferrara JL, Levine JE, Reddy P, Holler E. Graft-versus-host disease. Lancet. 2009;373:1550–1561. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60237-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hill GR, Kuns RD, Raffelt NC, et al. SOCS3 regulates graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2010;116:287–296. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-259598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murata M, Fujimoto M, Matsushita T, et al. Clinical association of serum interleukin-17 levels in systemic sclerosis: is systemic sclerosis a Th17 disease? J Dermatol Sci. 2008;50:240–242. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yoshizaki A, Yanaba K, Iwata Y, et al. Cell adhesion molecules regulate fibrotic process via Th1/Th2/Th17 cell balance in a bleomycin-induced scleroderma model. J Immunol. 2010;185:2502–2515. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sakaguchi S, Ono M, Setoguchi R, et al. Foxp3+ CD25+ CD4+ natural regulatory T cells in dominant self-tolerance and autoimmune disease. Immunol Rev. 2006;212:8–27. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matsuoka K, Kim HT, McDonough S, et al. Altered regulatory T cell homeostasis in patients with CD4+ lymphopenia following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:1479–1493. doi: 10.1172/JCI41072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zorn E, Kim HT, Lee SJ, et al. Reduced frequency of FOXP3+ CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in patients with chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2005;106:2903–2911. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rieger K, Loddenkemper C, Maul J, et al. Mucosal FOXP3+ regulatory T cells are numerically deficient in acute and chronic GvHD. Blood. 2006;107:1717–1723. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Banovic T, MacDonald KPA, Morris ES, et al. TGF-beta in allogeneic stem cell transplantation: friend or foe? Blood. 2005;106:2206–2214. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhao XY, Xu LL, Lu SY, Huang XJ. IL-17-producing T cells contribute to acute graft-versus-host disease in patients undergoing unmanipulated blood and marrow transplantation. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41:514–526. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sun LX, Ren HY, Shi YJ, Wang LH, Qiu ZX. Recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor significantly decreases the expression of CXCR3 and CCR6 on T cells and preferentially induces T helper cells to a T helper 17 phenotype in peripheral blood harvests. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15:835–843. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Toh HC, Sun L, Soe Y, et al. G-CSF induces a potentially tolerant gene and immunophenotype profile in T cells in vivo. Clin Immunol. 2009;132:83–92. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2009.03.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yi T, Chen Y, Wang L, et al. Reciprocal differentiation and tissue-specific pathogenesis of Th1, Th2, and Th17 cells in graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2009;114:3101–3112. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-219402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bettelli E, Korn T, Kuchroo VK. Th17: The third member of the effector T cell Trilogy. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19:652–657. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]