There is an enormous gap between demand for services for mental health disorders and available resources such as staff, finances, materials, and infrastructures for care delivery in Malawi. Studies have shown effectiveness of home treatment compared to institutional care for people with mental health problems in terms of outcomes and cost-effectiveness and subsequent compliance to medication1,2. Regular visits to provide psychiatric care at home and concerted efforts by health and social workers have been associated with reduced hospitalisation for people with mental health problemsiii.

In Malawi, mental health care services are largely institutionalized. Services are partially provided in all District Hospitals. There are three specialized mental health institutions, Zomba Mental Hospital (332 beds) in the southern region, Bwaila Psychiatric Unit (30 bed short stay unit) in the central region and St John of God Community Services (39 bed unit) in the northern region of Malawi. St John of God is the only referral hospital in the northern region covering a population of about one million people. The hospital receives clients referred from Christian Health Association of Malawi (CHAM) Hospitals and five Government District Hospitals in the region.

As in many other countries, the available mental health facilities in Malawi are not enough to meet the needs of many patients requiring admission for psychiatric illness In developed countries, home based care has been an effective alternative to hospital admission, therefore reducing the number of psychiatric beds required. Domiciliary mental health care is one example of such a service that is being promoted in Geriatric, Psychiatric and even general medicine ii .

Domiciliary mental health care is defined as care and support of clients with acute mental illness and challenging behaviour outside hospital, as far as possible, for purposes of restoring and maintaining health while maintaining clients in their usual place of residenceiv. This approach empowers family members to be primary caregivers to clients while increasing their understanding of the illness and consequently decreasing their tension and stressv.

This paper highlights successes and lessons learnt in the domiciliary mental health care approach that St. John of God Community Services has been implementing in the Northern city of Mzuzu since 2005. (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Showing a Clinical officer and nurse in one of the homes when the program just started in 2005

Programme Objectives

The broad objective of this programme is to provide alternative community based care to clients with mental health problems in the city of Mzuzu. The specific objectives are:

to offer home-based mental health care to clients within their homes;

to provide family education on mental health promotion and care in the home;

to enhance family and community participation in promoting the mental health of individuals with psychiatric problems while maintaining family cohesiveness;

and to alleviate the stigma associated with admission to a mental health facility, through family and community involvement in clients' care.

Client Recruitment/Admission into the Programme

The decision to put a client on domiciliary mental health care programme (DC) is based on the assessment by the clinicians or the senior psychiatric mental health nurses working at St. John of God Out-patient clinic in the city centre. Such clients normally come from within a radius of 10 kilometres from the clinic, for logistical purposes. Clients who are acutely sick, but who are not a danger to self or others in the home or community, are identified as suitable for the domiciliary mental health care programme. Those with suicidal ideations and risk for injury to other people are admitted in the psychiatric hospital, the House of Hospitality. There is no age limitation to client recruitment.

To alleviate fear among guardians, before a decision is made to put a client on the domiciliary mental health care programme, the family members and staff agree to work together after sharing adequate information about the client's care.

Programme Strategies

There three main strategies for providing domiciliary mental health care to clients in the catchment area.

A. Home visitations

Community psychiatric nurses (CPNs) conduct two or three home visits a day to provide nursing care to the clients and give psychotropic medication in their homes. The numbers of visits reduce depending on the client's response to interventions. One mental health provider has a maximum of four clients per day to care for. Flexible, personalised care plans and nursing interventions for structured and therapeutic support are done in the homes to enable clients to attain their optimum level of recovery, function and independence. Motorcycles are normally used by the CPNs except when working in a team.

The activities that are done in the home include: assessment of the client's home environment; provision of nursing and medical care; monitoring progress of the client and alleviating any fears for family/client; monitoring drug compliance and managing side effects; psycho-education to the client and his/her family on the nature of illness and management; documentation of all proceedings in the client's file; and referral of the client to hospital if necessary.

B. Mobile Team

Alongside the home visitation is a stand-by mobile team comprising two full time nurses and a clinical officer-on-call. These provide a back-up service to support the family care of clients in their homes. This may be utilised when the CPNs are overwhelmed by a difficult client situation. The team operates like a Mental Health emergency rapid response team daily on a 24 hour basis to respond to the needs of families. The team can be reached on an official mobile phone and CPNs or families can flash and will be called back. A social worker, counsellor and other multi-dimension team members can join the team as required.

C. Mental health education

To heighten public awareness about mental illnesses and to empower family members with skills for patient care, there are varied community mental health education programmes completed in the community and homes. The educational sessions within a family are chosen depending on the identified needs during each visit. Information often given to clients and guardians include: identification of psychiatric symptoms; drug dosages, duration and their action in the body; side effects and what to do; disease process; basic skills for managing mental health symptoms; and advice. This is given with practical support and assistance on compliance with prescribed medication.

Termination Process and Discharge Criteria

During the initial visit, termination process and discharge plans are drawn. The termination or discharge normally starts after symptoms have been managed and when the client is functioning well. The discharged clients are then referred back to St John of God outpatient department or their nearest psychiatric clinic for continuation of their treatment. Some clients may further be referred to the St John of God Institute of Vocational Training Centre (which is within the community) to regain or restore the lost functional skills and/or to acquire new vocational and social skills.

Successes

Since the establishment of this programme in 2005, 275 clients have recovered and attained an optimum level of functioning, without being admitted to hospital. According to statistics on duration of care, there appear to be significant reductions in the number of care days and recovery periods for clients on the domiciliary mental health care programme, when compared with those in residential unit. For example remission of acute symptoms for clients on a domiciliary mental health care programme starts after 15 to 35 days, compared to an average of 42 days taken for those hospitalized at the inpatient facility.

There has also been an increased awareness and understanding by families and communities on mental health, mental illness and care as well as enhanced family and community involvement in clients' care. Home based care also reduces the stigma associated with admission to a psychiatric hospital, enabling the clients to enjoy the freedom of staying in their own home while receiving care.

Looking at bed occupancy rate, there has been a reduction in the number of admissions, from the immediate catchment area, leading to cost-effectiveness in mental health care for those people from Mzuzu city.

Challenges

Despite the remarkable successes mentioned above, there are also some challenges that the programme is encountering. Owing to fears of how they might cope with their relative's behaviour, and because of past experiences, some carers still prefer that their client should be managed in the hospital even when the client is manageable at home. Even after education and support some family members continue to have negative attitudes towards the mentally ill. For instance one patient always reported that her guardian regularly shouted, beat her and tied her up, and only released her when the nurse was expected to come. However the team is aware of these challenges and efforts are made to minimize them.

Implication and Conclusion

There is evidence that visiting patients at home regularly and taking responsibility for both health and social care needs reduces admission days in hospital. Domiciliary mental health care is cost-effective and feasible in Malawi provided families are given the necessary support by health care workers within their respective communities.

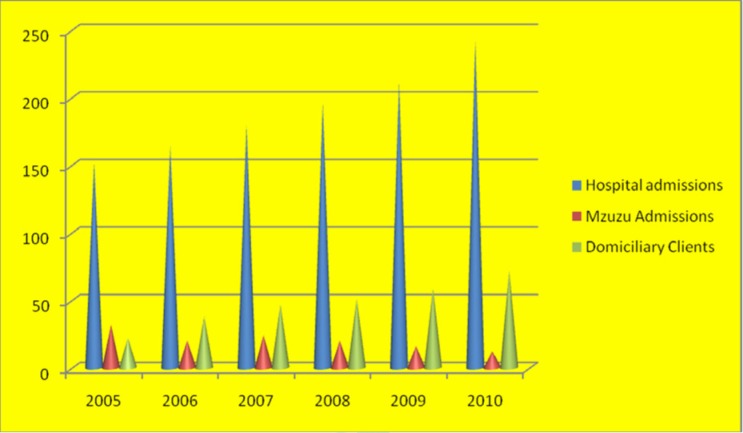

Figure 2.

Showing the reduction in clients admitted for within Mzuzu city as a result of strengthening the Domiciliary Care program, since 2005 to 2010.

Acknowledgements

I would like to extend my appreciation to St. John of God Staff for their kindness to release statistics that helped in the complication of this report.

References

- 1.Harrison J, Alam N, Marshall J. Home or away which patients are suitable for psychiatric home treatment service? Psych Bulletin. 2001;25:310–313. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burns T, Knapp M. Home treatment for mental health problems: A systematic review. Health Technol Assess. 2001;5(15):1–139. doi: 10.3310/hta5150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelly M, Newstead L. Family intervention in routine practice: it is possible. J Psych & Mental Health Nursing. 2004;11:64–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2004.00689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell MD. Psychiatric Dictionary. 7th ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fly J, Alam N, Marshal J. Domiciliary consultations: soma facts and questions. BMJ. 1988;30(6644):337–390. doi: 10.1136/bmj.297.6644.337. 297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]