Abstract

Histoplasmosis is a common endemic mycosis. The majority of infections involving this dimorphic fungus are asymptomatic. Manifestations in symptomatic patients are diverse, ranging from flu-like illness to a more serious disseminated disease. We present here a case of chronic disseminated histoplasmosis mimicking a metastatic cancer. We reviewed the literature for cases of disseminated histoplasmosis presenting with hypercalcemia, focusing particularly on clinical presentation, risk factors predisposing for fungal infection, and outcome. We report a case of a 65-year-old diabetic male who presented with unexplained weight loss and hypercalcemia. Multiple brain space-occupying lesions and bilateral adrenal enlargement were evident on imaging studies. Biopsies showed caseating granulomas with budding yeast, consistent with histoplasmosis. The patient’s symptoms resolved after liposomal amphotericin B and itraconazole therapy. Granulomatous diseases, including fungal infections, should be considered alongside malignancies, in patients with similar presentation.

Keywords: disseminated histoplasmosis, hypercalcemia

Introduction

Histoplasmosis is a fungal infection caused by the dimorphic fungus, Histoplasma capsulatum. It is the most common endemic mycosis in the United States.1 It is most prevalent around the valleys of the Mississippi and Ohio rivers.2 In endemic areas, 50%–80% of people have evidence of previous exposure to histoplasma.3 The fungus grows as a mold in the soil and when its microconidia are inhaled, causes infection and grows as a yeast in the host tissues. Most infected people remain asymptomatic or complain of a self-limiting flu-like illness. Up to 25% of people infected with human immunodeficiency virus will develop disseminated histoplasmosis, with considerable morbidity and mortality.3 Infection outside endemic areas and atypical presentations represent a diagnostic challenge. We present a case of progressive disseminated histoplasmosis manifesting as a wasting syndrome with hypercalcemia, mimicking a metastatic cancer.

Case report

A 65-year-old, type 2 diabetic man presented with a 2-month history of constipation, polyuria, and unexplained weight loss of 54 lb. There was no fever or chills and no respiratory symptoms. The patient was a lifelong smoker. He had lived in West Pennsylvania until 13 years earlier, when he had moved to the Texas Panhandle area where he presented with the above complaints. On physical examination, the patient was afebrile. He was confused and cachectic, without neck masses, lymphadenopathy, or organomegaly. The patient did not have skin rashes or mucosal ulcers. There were no heart murmurs and no adventitial lung sounds.

Laboratory test results revealed a hemoglobin of 10.6 (normal range 12–16) g/dL and a white blood cell count of 3.5 × 109 cells/L (normal range 4.0–10.6 × 109 cells/L). Biochemistry tests showed a creatinine of 3.2 (normal range 0.5–1.4) mg/dL, serum calcium of 12.4 (normal range 8.4–10.3) mg/dL, and albumin of 3.5 (normal range 3.7–5.1) g/dL. The patient’s parathyroid hormone level was low at 6 (normal range 11.0–54.0) pg/mL and serum protein electrophoresis showed a normal pattern.

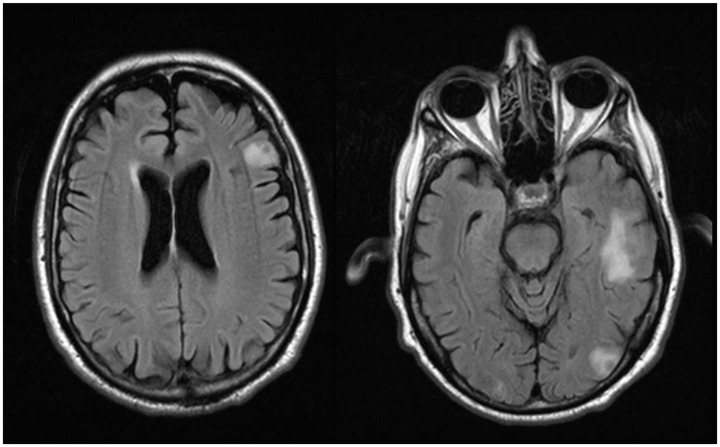

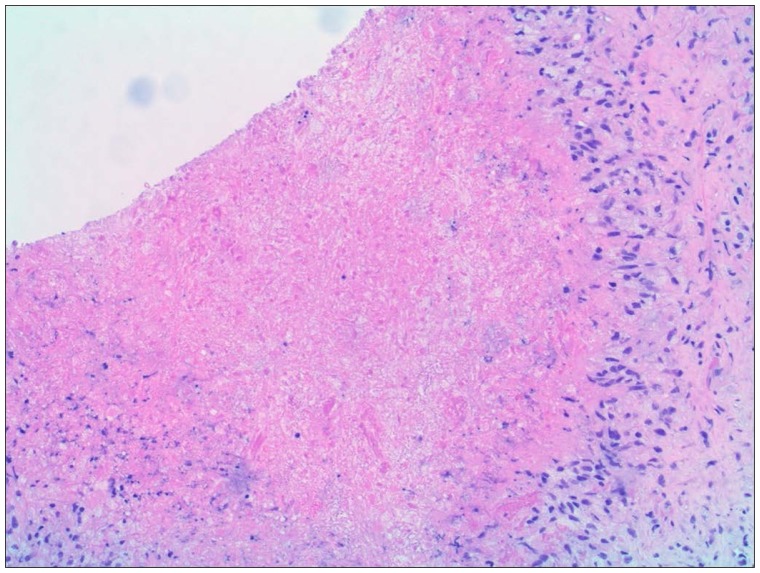

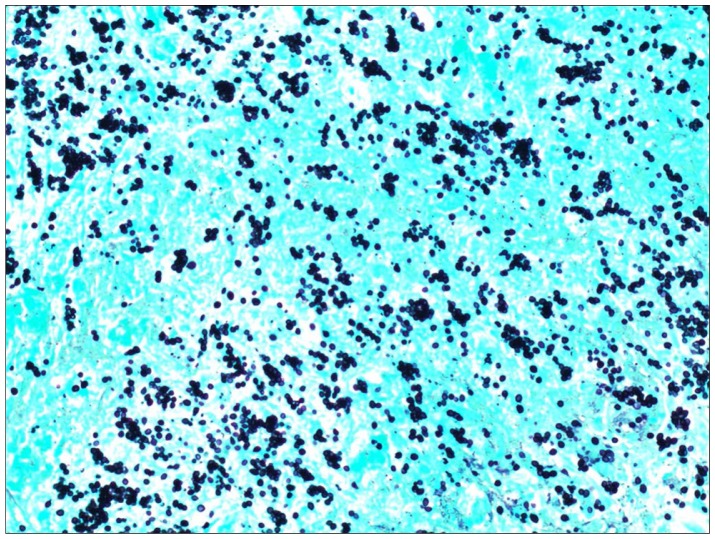

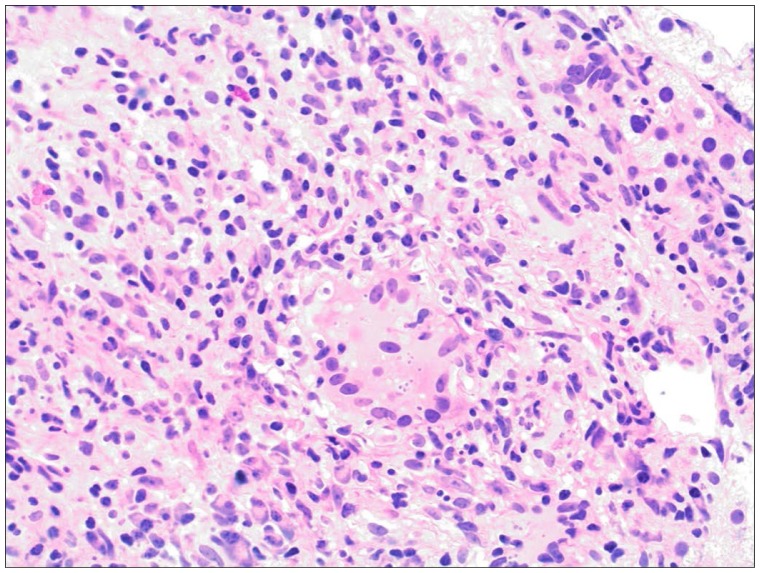

Body computed tomography showed bilateral adrenal enlargement and a mass lesion at the base of the tongue (Figure 1). Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed three left-sided brain lesions (Figure 2). Biopsies of the tongue lesion and the left adrenal gland showed necrotizing granulomas containing budding yeast forms, consistent with histoplasmosis (Figures 3–5). Biopsy tissue cultures were negative. The patient was diagnosed with chronic progressive disseminated histoplasmosis. Histoplasmosis is rarely diagnosed in the Texas Panhandle area and we were unable to tell whether his presentation represented a reactivation of an old infection or progression of a newly acquired infection. No other cases of histoplasmosis were diagnosed in our hospital during that time frame.

Figure 1.

Computed tomography of the abdomen showing enlarged adrenal glands, the left gland measured 6.8 × 6.7 × 2.7 cm.

Figure 2.

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (flare) showing three lesions in the left frontal, temporal, and occipital lobes.

Figure 3.

Adrenal needle biopsy section stained with hematoxylin and eosin showing necrotizing granuloma (original magnification, 10×).

Figure 5.

Adrenal needle biopsy section stained with Gomori methenamine silver showing small oval budding yeast typical of Histoplasma capsulatum (original magnification, 40×).

After adequate intravenous hydration, the patient’s kidney function tests and serum calcium level reverted to normal. The patient received a 4-week course of liposomal amphotericin B and was subsequently started on itraconazole. The patient’s symptoms resolved and he is being followed on regular basis.

Discussion

Dissemination of H. capsulatum is common in the early stages of this fungal infection.1 Symptomatic acute dissemination develops in immunocompromised patients.2 They present with a febrile illness that can be complicated by severe sepsis, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy. On the other hand, chronic progressive disseminated histoplasmosis is typically reported in middle-aged and elderly men who are not immunosuppressed.3 They present with a wasting syndrome, long-standing fever, and night sweats. The infection may involve multiple organ systems, including the gastrointestinal tract (with resulting ulceration), adrenal glands (precipitating adrenal insufficiency), the reticuloendothelial system (causing hepatosplenomegaly), bone marrow (leading to pancytopenia), the central nervous system, and the lungs. On rare occasions, progressive disseminated histoplasmosis has been associated with hypercalcemia, and this is attributed to increased 1, 25 dihydroxyvitamin D production from the fungal granulomas.4–10

A Medline search (January, 1946 to November, 2012) identified seven reported cases of disseminated histoplasmosis presenting with hypercalcemia. The clinical presentation, risk factors that predisposed to histoplasmosis, and patient outcomes are reported (Table 1). Upon reviewing the cases and in comparison with the case at hand, the following features were noted. Like our patient, most patients were middle-aged and elderly men with a limited degree of immunosuppression. Presenting symptoms varied, with pulmonary complaints in two cases, gastrointestinal symptoms in two, wasting syndrome in three, including ours, and musculoskeletal complaints in another. Hypercalcemia was symptomatic in some cases and an asymptomatic laboratory abnormality in others. In all cases, the diagnosis was difficult to make, and in three cases was established post mortem. Mortality was high, with 37.5% of the patients dying. Two of the three patients who died, ie, the first and second cases, did not receive antifungal therapy, and treatment was delayed in the third patient who died, ie, the fourth case.

Table 1.

Reported cases of progressive disseminated histoplasmosis presenting with hypercalcemia

| Age/gender | Risk factors | Presenting symptoms | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 56 years, M | Splenectomy and steroid therapy | Fever, malaise, nausea, vomiting, confusion weight loss | 4 |

| 62 years, M | DM | Malaise, anorexia, weight loss | 5 |

| 10 months, M | Immature immunity | Failure to thrive | 6 |

| 46 years, M | Malnutrition due to chronic diarrhea | Fever, diarrhea, papular skin rash | 7 |

| 47 years, M | None | Right hand tenosynovitis | 8 |

| 40 years, F | RA on infliximab, methotrexate, and prednisone | Fever, cough, nodular pulmonary infiltate, lymphadenopathy | 9 |

| 61 years, M | None | Cough, dyspnea, cavitating pulmonary lesions | 10 |

| 65 years, M | DM | Unexplained weight loss | Current case |

Abbreviations: DM, diabetes mellitus; F, female; M, male; RA, rheumatoid arthritis.

Diagnosis of histoplasmosis relies on a multifaceted approach.11 Histopathological examination, cultures, antigen and antibody detection, and molecular methods are commonly used in different combinations to establish the diagnosis. A recent multicenter study evaluated the above-mentioned tests in the diagnosis of disseminated histoplasmosis and reported their corresponding sensitivities, ie, 74% for cultures, 76% for histopathology, 92% for antigen detection in urine and/or serum using a third-generation enzyme immunoassay, and 75% for antibody detection combining immunodiffusion and complement fixation assays.11 Use of molecular methods in the diagnosis of histoplasmosis has been reported, but remains uncertain and is awaiting further study.12

The high sensitivity of antigen detection is plagued by significant cross-reactivity with other fungal antigens. Cross-reaction occurs in 90% of patients with blastomycosis and in 60% of patients with coccidioidomycosis.13 Testing both urine and serum yields better sensitivity. Furthermore, testing cerebrospinal fluid and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid might improve sensitivity in diagnosing central nervous system and pulmonary infections.14 It is worth mentioning that failure to detect histoplasma antigens does not rule out the diagnosis, and repeating the test in patients with progressive illness should be considered.3

Severity of illness dictates antifungal treatment options and duration of therapy. For moderate to severe infection, liposomal amphotericin B for 1–2 weeks followed by a 12-month course of itraconazole is recommended.15 For milder cases, itraconazole for one year is indicated. Itraconazole blood levels should be measured to ensure adequate drug exposure. For histoplasmosis of the central nervous system, liposomal amphotericin B for 4–6 weeks followed by itraconazole for at least one year and until cerebrospinal fluid abnormalities and antigenemia or antigenuria resolve is recommended.15 Antigen levels in serum or urine should be measured during therapy for progressive disseminated histoplasmosis and central nervous system infection, and for 12 months afterwards. Ten percent to 15% of patients experience a relapse.16 Diagnosis and treatment in this group of patients follows the above outlined principles, but also includes long-term itraconazole maintenance therapy.

Our work has some limitations, not the least of which is the fact that it is a single case report. Furthermore, the diagnosis was based on a compatible clinical presentation and histopathological examination that could not be confirmed by culture, serology, or antigen detection. Further research is needed to develop readily available tests, probably molecular diagnostic methods, with higher sensitivity and specificity to diagnosis histoplasmosis as well as other mycosis. Efforts to develop safer and more effective antifungal drugs would also be worthwhile.

Conclusion

Progressive disseminated histoplasmosis is a fungal infection with diverse presentations. Acute disseminated infection presents with a sepsis syndrome, whereas chronic dissemination presents as a wasting syndrome. There are rare manifestations of this mycosis that could delay diagnosis and compromise outcome. This infection is fatal if not treated. We reported here a case of chronic disseminated histoplasmosis presenting with multiple mass lesions, weight loss, and hypercalcemia, mimicking metastatic cancer. The patient was treated successfully with appropriate antifungal therapy. In addition to malignancy, granulomatous disease, including fungal infection, should be considered in patients with similar presentation.

Figure 4.

Adrenal needle biopsy section stained with hematoxylin and eosin showing granulomatous inflammation and a multinucleated giant cell containing small yeast surrounded by halos representing fungal capsules (original magnification, 20×).

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Kauffman CA. Histoplasmosis. Clin Chest Med. 2009;30(2):217–225. v. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knox KS, Hage CA. Histoplasmosis. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2010;7(3):169–172. doi: 10.1513/pats.200907-069AL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Assi MA, Sandid MS, Baddour LM, Roberts GD, Walker RC. Systemic histoplasmosis: a 15-year retrospective institutional review of 111 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2007;86(3):162–169. doi: 10.1097/md.0b013e3180679130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walker JV, Baran D, Yakub N, Freeman RB. Histoplasmosis with hypercalcemia, renal failure, and papillary necrosis. Confusion with sarcoidosis. JAMA. 1977;237(13):1350–1352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murray JJ, Heim CR. Hypercalcemia in disseminated histoplasmosis. Aggravation by vitamin D. Am J Med. 1985;78(5):881–884. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(85)90300-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steele CJ, Kleiman MB. Disseminated histoplasmosis, hypercalcemia and failure to thrive. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1994;13(5):421–422. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199405000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu JW, Huang TC, Lu YC, et al. Acute disseminated histoplasmosis complicated with hypercalcaemia. J Infect. 1999;39(1):88–90. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(99)90108-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liang KV, Ryu JH, Matteson EL. Histoplasmosis with tenosynovitis of the hand and hypercalcemia mimicking sarcoidosis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2004;10(3):138–142. doi: 10.1097/01.rhu.0000128177.98388.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kamili QA, Menter A. Atypical presentation of histoplasmosis in a patient with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis on infliximab therapy. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9(1):57–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chalhoub E, Elhomsy G, Brake M. Hypercalcemia in histoplasmosis aggravated with antifungal treatment. J Med Liban. 2012;60(3):165–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hage CA, Ribes JA, Wengenack NL, et al. A multicenter evaluation of tests for diagnosis of histoplasmosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(5):448–454. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bracca A, Tosello ME, Girardini JE, Amigot SL, Gomez C, Serra E. Molecular detection of Histoplasma capsulatum var. capsulatum in human clinical samples. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41(4):1753–1755. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.4.1753-1755.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Connolly PA, Durkin MM, Lemonte AM, Hackett EJ, Wheat LJ. Detection of histoplasma antigen by a quantitative enzyme immunoassay. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2007;14(12):1587–1591. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00071-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hage CA, Davis TE, Fuller D, et al. Diagnosis of histoplasmosis by antigen detection in BAL fluid. Chest. 2010;137(3):623–628. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wheat LJ, Freifeld AG, Kleiman MB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with histoplasmosis: 2007 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(7):807–825. doi: 10.1086/521259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wheat J, Hafner R, Korzun AH, et al. Itraconazole treatment of disseminated histoplasmosis in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. AIDS Clinical Trial Group. Am J Med. 1995;98(4):336–342. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)80311-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]