Abstract

The dramatic differences between the properties of molecules formed from the late p-block elements of the first row of the periodic table (N–F) and those of the corresponding elements in subsequent rows is well recognized as the first row anomaly. Certain properties of the atoms, such as the relative energies and spatial extents of the ns and np orbitals, can explain some of these differences, but not others.

In this Account, we summarize the results of our recent computational studies of the halides of the late p-block elements. Our studies point to a single underlying cause for many of these differences: the ability of the late p-block elements in the second and subsequent rows of the periodic table to form recoupled pair bonds and recoupled pair bond dyads with very electronegative ligands. Recoupled pair bonds form when an electron in a singly occupied ligand orbital recouples the pair of electrons in a doubly occupied lone pair orbital on the central atom, leading to a central atom-ligand bond. Recoupled pair bond dyads occur when a second ligand forms a bond with the orbital left over from the initial recoupled pair bond.

Recoupled pair bonds and recoupled pair bond dyads enable the late p-block elements to form remarkably stable hypervalent compounds such as PF5 and SF6 and lead to unexpected excited states in smaller halides of the late p-block elements such as SF and SF2. Recoupled pair bonding also causes the Fn–1X–F bond energies to oscillate dramatically once the normal valences of the central atoms have been satisfied. In addition, recoupled pair bonding provides a lower-energy pathway for inversion in heavily fluorinated compounds (PF3 and PF2H, but not PH2F and PH3) and leads to unusual intermediates and products in reactions involving halogens and late p-block element compounds, such as (CH3)2S + F2.

Although this Account focuses on the halides of the second row, late p-block elements, recoupled pair bonds and recoupled pair bond dyads are important in the chemistry of p-block elements beyond the second row (As, Se, and Br) and for compounds of these elements with other very electronegative ligands, such as OH and O. Knowledge of recoupled pair bonding is thus critical to understanding the properties and reactivity of molecules containing the late p-block elements beyond the first row.

1. Introduction

The dramatic differences in the properties of molecules formed from p-block elements in the first and subsequent rows of the periodic table have long been recognized. In Inorganic Chemistry, Third Edition, G. L. Miessler and D. A. Tarr1 state that:

The main group elements show the “first-row anomaly” (counting the elements Li through Ne as the first row). Properties of elements in this row are frequently significantly different from properties of the other elements in the same group. (p. 245)

Some differences can be attributed to differences in the properties of the atoms, for example, the relative energies and spatial extents of the ns and np orbitals. Other differences cannot be so easily explained. These include:

-

•

Hypervalent species that only exist for elements beyond the first row.

-

•

Excited states that are absent or barely bound in first row compounds.

-

•

Variations in sequential (Fn–1X–F/Cl) bond energies.

-

•

New transition states for molecular inversion.

-

•

Fast chemical reactions between closed shell molecules.

Musher2 and Kutzelnigg3 discussed some of the differences between the properties of the first and second row elements. Our recent theoretical and computational studies of the second row halides4−11 have shed further light on these anomalies: all of the above differences can be explained by the ability of the second row, late p-block elements to form a new type of chemical bond—the recoupled pair bond. A recoupled pair bond is formed when an electron in a singly occupied ligand orbital recouples the pair of electrons in a formally doubly occupied lone pair orbital on a central atom, forming a central atom-ligand bond.

Although the focus in this Account is on the second row halides, recoupled pair bonds are also found in third row element halides4 and in molecules with other electronegative ligands, for example, hydroxyl radical and oxygen atom.12 Thus, knowledge of recoupled pair bonding is critical to understanding the properties and reactivity of molecules containing the late p-block elements beyond the first row.

Recoupled pair bonds also occur in the early p-block elements. Beryllium cannot form bonds with monovalent ligands unless its 2s2 pair is recoupled, while the 2s2 pairs of boron and carbon must be recoupled to form di/tri- and tri/tetravalent compounds, respectively. Goddard and co-workers13,14 investigated recoupled pair bonding for these elements, although they did not use this terminology. Nonetheless, their model of bonding in the early p-block elements is essentially equivalent to the model described herein. Recoupled pair bonds account for the bonding in early p-block elements without the need for the ad hoc introduction of spn hybrids.15

2. Theoretical and Computational Details

Two strengths of modern quantum chemistry are the ability to make accurate predictions of the properties of molecules using highly correlated wave functions and the ability to explain the trends in these properties using orbital-based theories.

Methods capable of yielding highly accurate solutions of the electronic Schrödinger equation have been employed in the current studies—single-reference restricted singles and doubles coupled cluster theory with perturbative triples [CCSD(T), RCCSD(T)] and multireference configuration interaction (MRCI) calculations based on complete active space self-consistent field (CASSCF) wave functions with the quadruples correction (+Q).16−19 Augmented correlation consistent basis sets of quadruple-ζ (aug-cc-pVQZ) or better quality, including sets augmented with tight d-functions for the second row atoms, were used to ensure solutions close to the complete basis set limit.20,21

Generalized valence bond (GVB)/spin-coupled valence bond (SCVB) calculations provided invaluable insights into the electronic structure and properties of the molecules studied here.13,22,23 The GVB wave function corrects the major deficiencies in valence bond (VB) and Hartree–Fock (HF) wave functions and is usually the dominant component of a valence CASSCF wave function.24,25 In the GVB wave function, the orbitals vary continuously from the atomic or fragment orbitals at large separations to orbitals appropriate for the molecule as the internuclear separation decreases. Similarly, the spin function changes to reflect the recoupling of the electrons in the molecule. Here, we use the GVB wave function with strong orthogonality (SO) constraints—GVB(SO)—since this wave function is closely related to the HF wave function, allowing us to use familiar terms to explain the new bonding concepts introduced in our work. All calculations were performed with Molpro.26

3. Bonding with the Late p-Block Elements

The structures and energies of the low-lying states of the halides of the second row, late p-block elements are determined by the interplay between the formation of covalent and recoupled pair bonds. Here, we use the SFn molecules to illustrate this interplay. To understand the bonding in SFn molecules, we build them by successive F atom additions: SFn-1 + F → SFn. This approach provides unrivaled insights into the nature of the bonding in these species. For a detailed discussion of the electronic structure of the SFn molecules as well as the other halides studied by our group to date—ClFn, PFn, SFn-1Cl, and SCln—see the original articles.4−11

3.1. Covalent and Recoupled Pair Bonds in SF

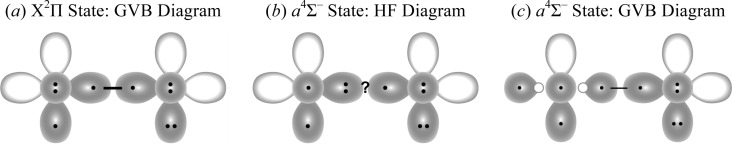

The difference between covalent and recoupled pair bonds can be illustrated by considering the ground (X2Π) and first excited (a4Σ–) state of monosulfur monofluoride. The bond in ground state SF is a covalent bond, while that in excited state SF (SF*) is a recoupled pair bond. The orbital diagrams for the ground and excited states of SF are given in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Orbital diagrams for the ground (X2Π) and first excited (a4Σ–) states of SF. Only the p orbitals and their occupancies (as dots) are shown. Positive lobes are dark, and negative lobes light.

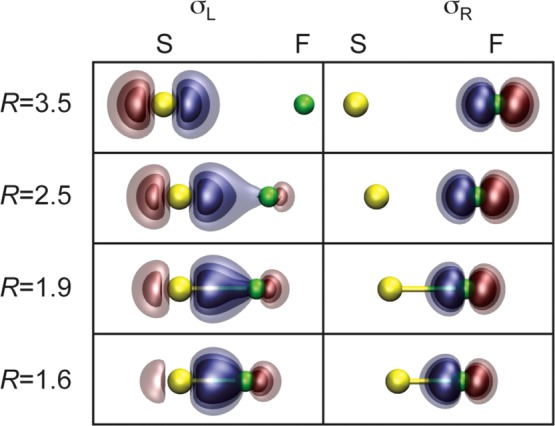

The S–F bond in the ground state is formed by singlet coupling the electrons in the singly occupied S(3pz) and F(2pz) orbitals, forming a classical Heitler–London bond pair. The two GVB(SO) bonding orbitals are plotted in Figure 2. At large internuclear separation (R = 3.5 Å), the two orbitals are just S(3pz) and F(2pz) atomic orbitals. As R decreases, the S(3pz) orbital polarizes toward and delocalizes onto the F atom, increasing its overlap with the F(2pz) orbital and building ionic Sδ+Fδ− character into the wave function. The F(2pz) orbital is little affected by molecular formation. At the equilibrium internuclear separation (Re ≈ 1.6 Å), the SF bond is clearly a polar covalent bond, reflecting the relative electronegativities of sulfur and fluorine. The other valence orbitals also change in important ways upon molecular formation but are not discussed here.5

Figure 2.

Plots of the GVB(SO) bonding orbitals for the ground (X2Π) state of SF at selected internuclear separations R (left, Å). Re ≈ 1.6 Å.

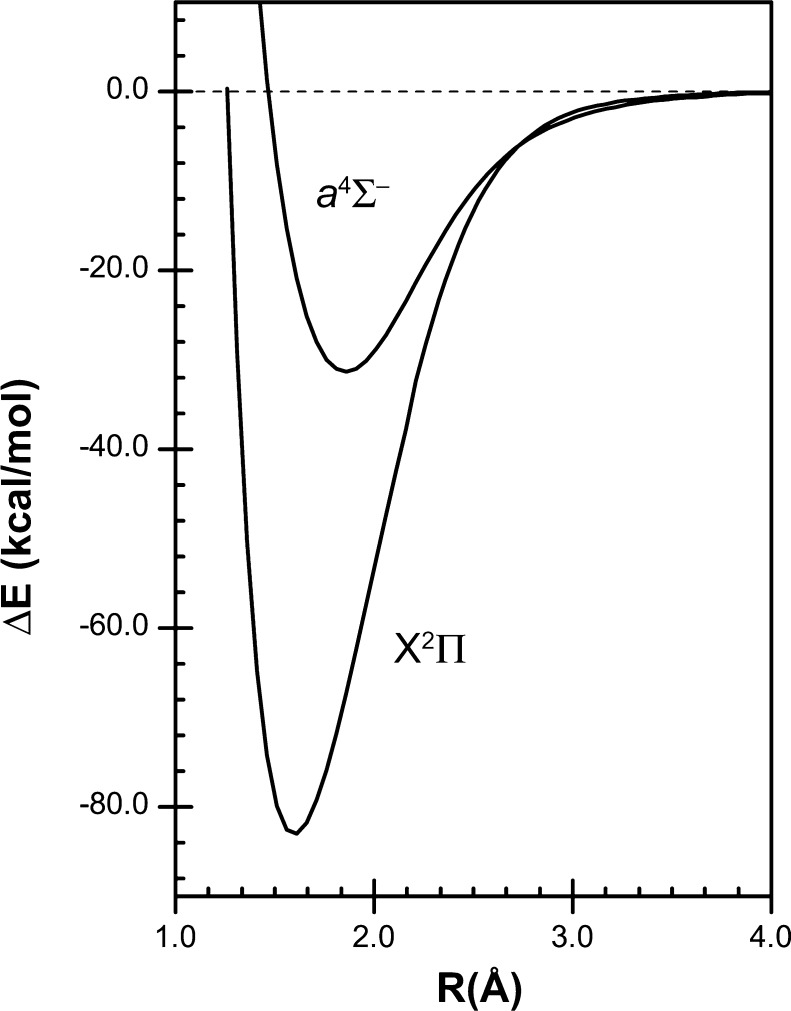

Based on the HF orbital diagram for SF* in Figure 1b, with three electrons in σ orbitals, the resulting potential energy curve might be expected to be repulsive. This is not the case. The calculated potential energy curves for the ground and excited states of SF are plotted in Figure 3. Although the calculated dissociation energy (De) for SF*, 36.2 kcal/mol, is less than that for SF, 83.3 kcal/mol, it is still significant. In line with the weak SF* bond, the calculated Re(SF*), 1.882 Å, is significantly longer than that in SF, 1.601 Å.27

Figure 3.

Calculated potential energy curves for the ground (X2Π) and first excited (a4Σ–) states of SF. Method: (MRCI+Q)/aug-cc-pV(Q+d)Z.

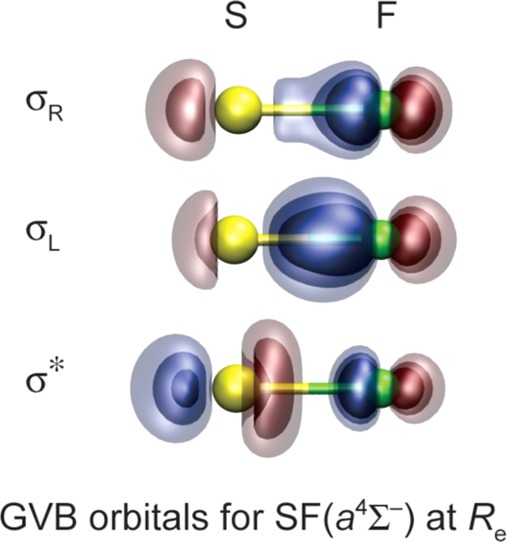

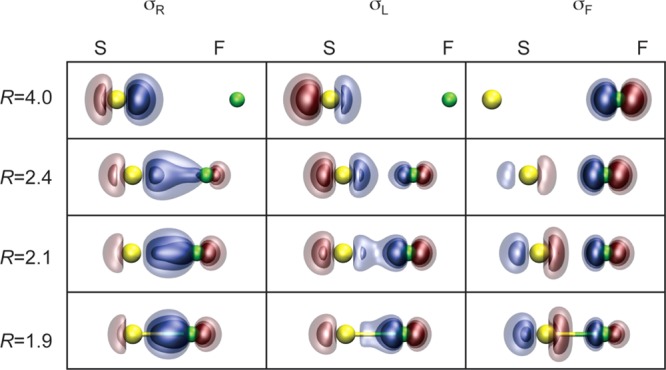

Three electrons and three GVB orbitals are involved in the formation of the bond in SF*; see Figures 1c and 4. In the Hartree–Fock wave function, the S(3pz) orbital is doubly occupied. In the GVB wave function, the 3pz2 configuration mixes in a 3dz22 configuration, resulting in a pair of S(3pz) lobe orbitals: one polarized toward the incoming F atom S(3pz+), the other polarized away from the F atom S(3pz–); see Figure 1c and the leftmost two orbitals (σR, σL) at the top of Figure 4. As R decreases, this pair of orbitals shifts toward the F atom, eventually becoming a very ionic Sδ+Fδ− bond pair. Simultaneously, the singly occupied orbital originally on the F atom acquires S(3pz) character, building in antibonding character (σ*). Since the S(3pz+) and S(3pz–) orbital pair is singlet coupled at large R and the polarized and delocalized S(3pz+) and F(2pz) orbital pair is singlet coupled at short R, we refer to the SF* bond as a recoupled pair bond.

Figure 4.

Plots of the three GVB(SO) orbitals involved in the recoupled pair bond in the SF(a4Σ–) state at selected internuclear separations R (left, in Å). Re ≈ 1.9 Å.

Although the S(3pz+,3pz–) lobe orbitals have 3d character, the 3d contribution is far smaller than required for a true pd hybrid—just a few percent. As a result, the energy lowering is small (4.9 kcal/mol) and the overlap between the S(3pz–,3pz+) orbitals is high, 0.85. This has significant implications for the formation of recoupled pair bonds involving late p-block elements:

-

•

The S(3pz+) and F(2pz) orbitals cannot strongly overlap to form a bond without simultaneously having a high overlap with the S(3pz–) orbital. Because of the Pauli Principle, this leads to substantial antibonding character in the S(3pz–) orbital as R decreases, resulting in a longer, weaker bond.

-

•

The antibonding character in the S(3pz–) orbital is minimized, and the strength of the SF bond maximized, if the bonding orbitals localize on the ligand at short R. Thus, recoupled pair bonds are only formed in the late p-bock elements with very electronegative ligands.

The above is a critical difference between recoupled pair bonding in the early and late p-block elements. In the early p-block elements, the 2s lobe orbitals are far more spatially separated than the (3pz+,3pz–) pair; for example, the overlap between the C(2s–,2s+) lobe orbitals is only 0.74.13 As a result, recoupled pair bonds in the early p-block elements can be formed with essentially any ligand.

3.2. Recoupled Pair Bond Dyad in SF2

Adding fluorine to SF and SF* leads to several low-lying states of SF2, one of which is the SF2 ground state with two covalent bonds. Another state, the a3B1 excited state of SF2 (SF2*), provides an illustrative example of a recoupled pair bond dyad.

The ground state of SF2 arises by singlet coupling the electrons in the singly occupied SF(3pπ) and F(2p) orbitals; see Figure 5a. For this state, De(F–SF) is slightly larger than that for SF, 91.0 vs 83.3 kcal/mol, but the bond lengths are nearly the same, 1.592 vs 1.601 Å. The F–S–F bond angle is close to that expected from forming a bond with the SF(3pπ) orbital, 97.9°.27

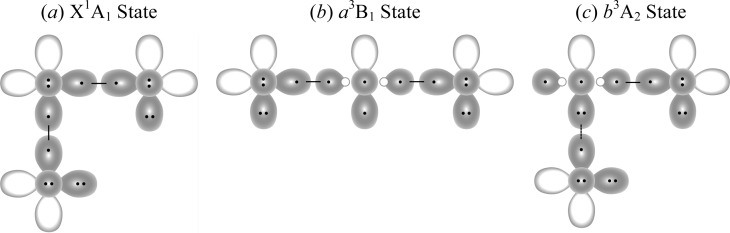

Figure 5.

Orbital diagrams for the low-lying states of SF2: (a) ground state SF2 (X1A1), (b) excited state SF2* (a3B1), and (c) excited state SF2** (b3A2).

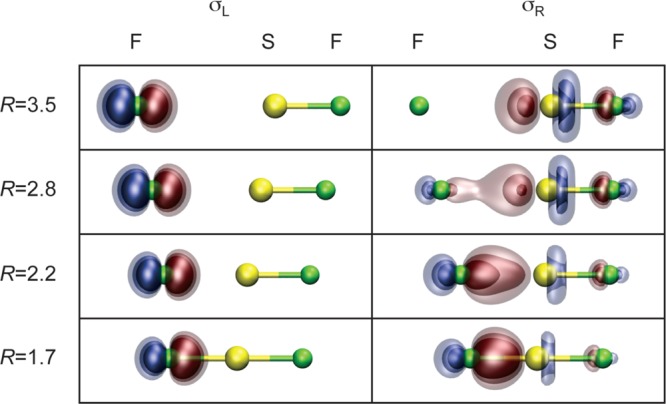

The lowest lying excited state of SF2 (SF2*) arises from F + SF* by singlet coupling the electrons in the singly occupied F(2p) and SF(σ*) antibonding orbitals; see Figure 5b. Although the resulting F–SF bond is a covalent bond, it is very strong—106.6 kcal/mol, 70 kcal/mol stronger than in SF* and nearly 16 kcal/mol stronger than F–SF. The bond length is also markedly less than that in the SF* state—1.666 Å vs 1.882 Å—although it is still longer than that in the SF2 ground state (1.601 Å). As expected, the SF2* molecular state has a nearly linear configuration, θe = 162.7°.

The reason for this remarkable change in bond strength and length is illustrated in Figure 6, which plots the two GVB orbitals involved in the bond as a function of the F–SF distance. As R decreases, the σ* antibonding orbital localizes more and more onto the incoming F atom. By the time Re is reached, there is very little antibonding character remaining in the orbital, resulting in a stronger, shorter bond. Because of the unusual strength of this bond, SF2* is calculated to lie only 32 kcal/mol above SF2.

Figure 6.

Plots of the GVB(SO) bonding orbitals for the F–SF(a4Σ–) covalent bond in the SF2(a3B1) state at selected internuclear separations R (left, Å). Re ≈ 1.7 Å.

The combination of a recoupled pair bond plus a covalent bond involving the resulting antibonding orbital is called a recoupled pair bond dyad. The dyad is the theoretical foundation for the three-center, four-electron (3c-4e) bond model of Rundle and Pimentel.28 However, there is a major conceptual difference between the two models—the (3c-4e) bond is described as a delocalized entity, whereas the recoupled pair bond dyad, which gives rise to the same dominant σb2σnb2 natural orbital configuration, is simply two very ionic, two-electron bonds, in agreement with the detailed analysis by Ponec et al.29 The wealth of new insights provided by the recoupled pair bonding model (see above and below) also suggests that it is far more useful than the (3c-4e) model.

Although the recoupled pair bond dyad is very stable, the two bonds in the dyad are linked in a manner that two covalent bonds are not—increasing the length of one of the bonds dramatically decreases the strength of the remaining bond.

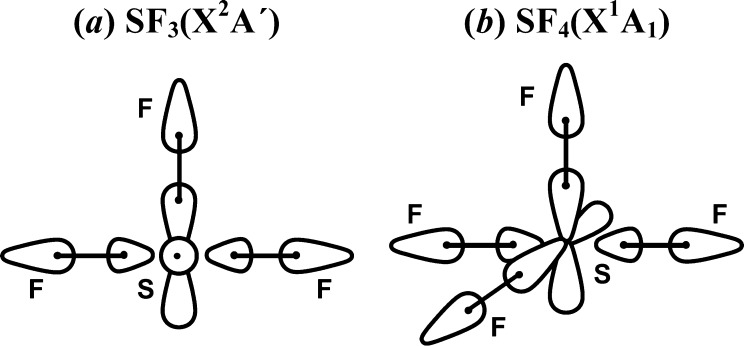

3.3. Multiple Bonding Pathways in SF3

There are multiple pathways for forming SF3 from F + SF2. The most relevant pathway is F + SF2*. This pathway involves formation of a covalent bond and predicts SF3 to have one covalent bond, a recoupled pair bond dyad and a singly occupied S(3p)-like orbital in addition to a doubly occupied S(3s)-like orbital. This is consistent with the calculated ground state structure of SF3 (see Figures 7a and 8) as well as the bond energy, 87.8 kcal/mol.

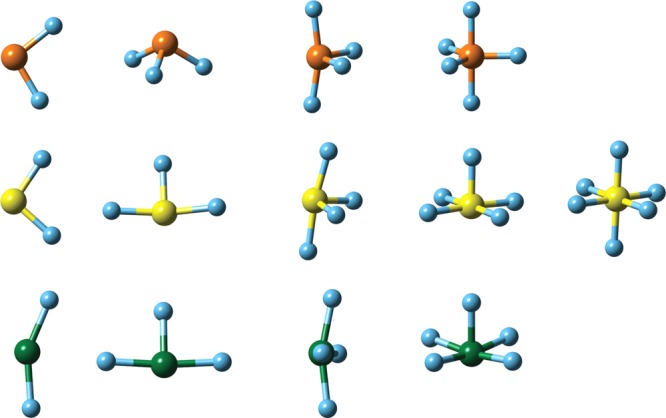

Figure 7.

Schematic orbital diagrams for (a) SF3 and (b) SF4.

Figure 8.

Calculated molecular structures of the ground states of the fluorides of phosphorus (top), sulfur (middle), and chlorine (bottom). Method: [CCSD(T),RCCSD(T)]/aug-cc-pV(Q+d)Z.

SF3 can also be formed from ground state SF2 and F. At large F–SF2 distances, the electron in the singly occupied F(2p) orbital begins to recouple the electrons in one of the SF2 lone pair orbitals. However, as the distance decreases, the orbitals rearrange to form the more favorable SF3 structure described above.5 The energy of SF3 relative to SF2 + F is 56.0 kcal/mol.

3.4. Stable Hypervalent Molecule, SF4

SF4 is produced from SF3 + F by forming a covalent bond; see Figure 7b. De(F3S–F) is 98.8 kcal/mol. The molecular structure of SF4 is derived directly from that of SF3: it has a sawhorse structure with the lengths of the covalent bonds (Re = 1.548 Å) and recoupled pair bond dyad (Re = 1.645 Å) differing from those in SF3 by only 0.01–0.02 Å. The bond angle between the equatorial F atoms is 101.4° and that between the axial F atoms is 172.1° (163.4° in SF3).27

3.5. Formation of SF5 and the Stable Hypervalent Molecule, SF6

Formation of SF5 and SF6 follows the principles outlined above with one distinction—in these molecules, the S(3s2)-like lone pair must be recoupled. SF5 has two recoupled pair bond dyads and a covalent bond. De(F4S–F) is 41.1 kcal/mol and the Re’s are 1.540 Å (covalent bond) and 1.595 Å (recoupled pair bond dyads). The F5S–F bond energy is the largest computed for SFn, 109.2 kcal/mol. SF6 has three recoupled pair bond dyads, with Re = 1.561 Å.27

3.6. Structures of XFn

The calculated structures of PFn, SFn, and ClFn are given in Figure 8. The interplay of covalent and recoupled pair bonds and dyads is clearly evident.

3.7. Hypervalency

Hypervalency was introduced by Musher,2 who defined it as “molecules and ions formed by elements in Groups V–VIII of the periodic table in any of their valences other than their lowest stable chemical valence of 3, 2, 1, and 0 respectively.” However, the concept of hypervalency has had a contentious history. This is largely a result of the ambiguity of assigning electrons to atoms, resulting in apparent violations of the octet rule; see McGrady and Steed.30 To bypass this problem, Schleyer31 introduced the term hypercoordinate to describe hypervalent compounds, “... as this provided an empirical characterization of their experimentally observed molecular structures without the necessity of having to endorse a particular view concerning the theoretical description of their electronic bonding.” As seen above, expanding the number of ligands beyond the nominal valence of the atoms follows naturally from the ability of the elements in the second row and beyond to form recoupled pair bonds combined with the remarkable stability of the recoupled pair bond dyad.

4. Impact of Recoupled Pair Bonding on the Halides of the Second Row, Late p-Block Elements

With the above as background, we are now in a position to consider the anomalous properties of the halides of the late p-block elements noted in the Introduction. For a more detailed discussion, see refs (4−11).

4.1. Low-Lying Excited States

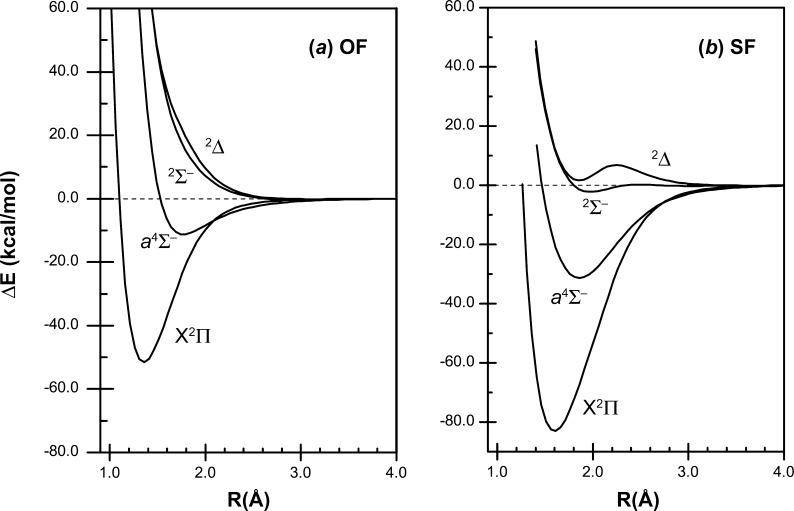

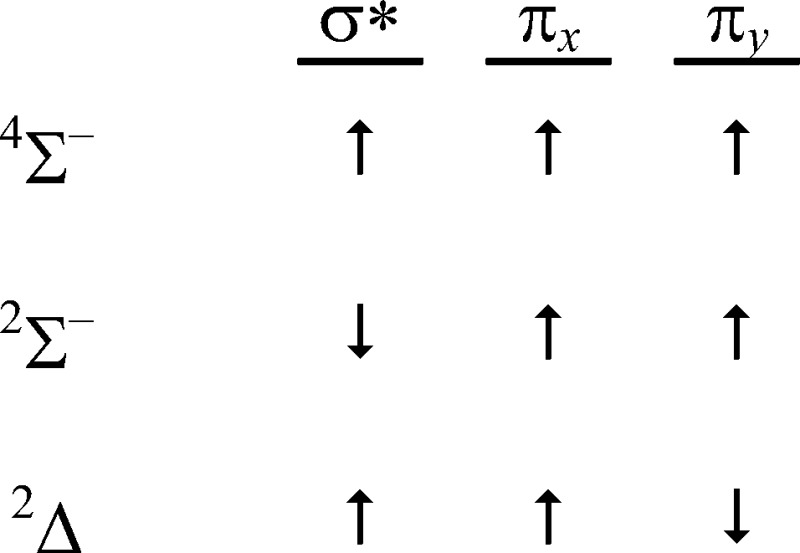

Recoupled pair bonds can occur in molecules with normal valence, but in excited states of these species. The SF*(a4Σ–) state is one example of such an excited state; recoupled pair bonding also gives rise to the other bound low-lying SF excited states in Figure 9. In fact, the orbital configurations for all three states are identical (σ*π2) with the differences being in the electron spin couplings:

Figure 9.

Calculated potential energy curves for the low-lying states of (a) OF and (b) SF. Method: (MRCI+Q)/aug-cc-pV(Q+d)Z.

The 4Σ– and 2Σ– states have the electrons in the π orbitals coupled into a triplet (↑↑), with the electron in the σ* orbital coupled with this triplet pair as either high spin (↑; 4Σ–) or low spin (↓; 2Σ–). These states arise from the S(3P) + F(2P) limit. The 2Δ state, which has the electrons in the π orbitals coupled into a singlet (↑↓), arises from the S(1D) + F(2P) limit, but there is an avoided crossing with the repulsive 2Δ state arising from the ground state limit, resulting in the observed hump in the potential energy curve. There are also higher lying excited states with recoupled pair bonds.

There are also a number of other low-lying bound states in SF2 with recoupled pair bonds. The SF2**(3A2) state arises when the F atom approaches the doubly occupied 3pπ-like orbital of SF (see Figure 5c), forming a recoupled pair bond. The calculated bond length is longer than that in the ground state, 1.656 vs 1.592 Å, and the bond angle is 83.1°. The calculated bond energy is 41.0 kcal/mol, and excitation energy, Te(b3A2), is 52.0 kcal/mol.

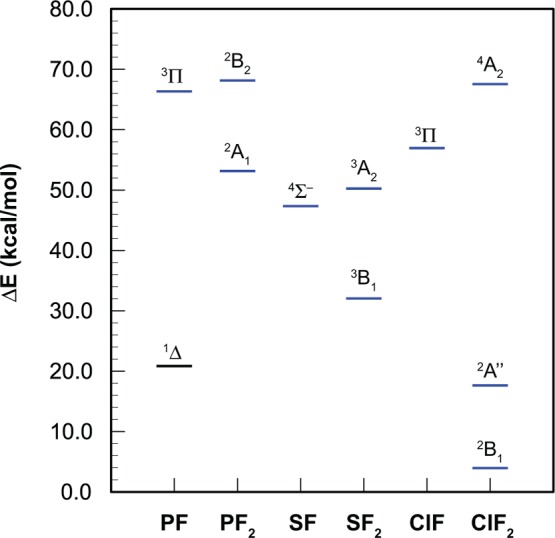

Excited states with recoupled pair bonds also arise in the other molecules we studied;4−11 these are summarized in Figure 10. In SFCl, recoupled pair bonding led to a state exhibiting bond length isomerism.8,11 However, the barriers between the isomers are so small that the presence of the isomers will only be signaled by complicated vibrational structure in the electronic spectra of SFCl.

Figure 10.

Calculated [CCSD(T)/RCCSD(T)] energy level diagram for selected low-lying excited states in XF and XF2. All but the PF(1Δ) state have recoupled pair bonds. Method: [CCSD(T),RCCSD(T)]/aug-cc-pV(Q+d)Z.

The model also accounts for the absence of hypervalency for first row compounds. As can be seen in Figure 9, the potential energy curve for the a4Σ– state in OF is only slightly bound, De = 11.0 kcal/mol.4 This state is an example of frustrated recoupled pair bonding. The small difference in the electronegativities of the F and O atoms prevents the F atom from completely recoupling the electrons in the O(2pz2) pair, leading to a very weakly bound excited state.

4.2. Bond Energy Variations

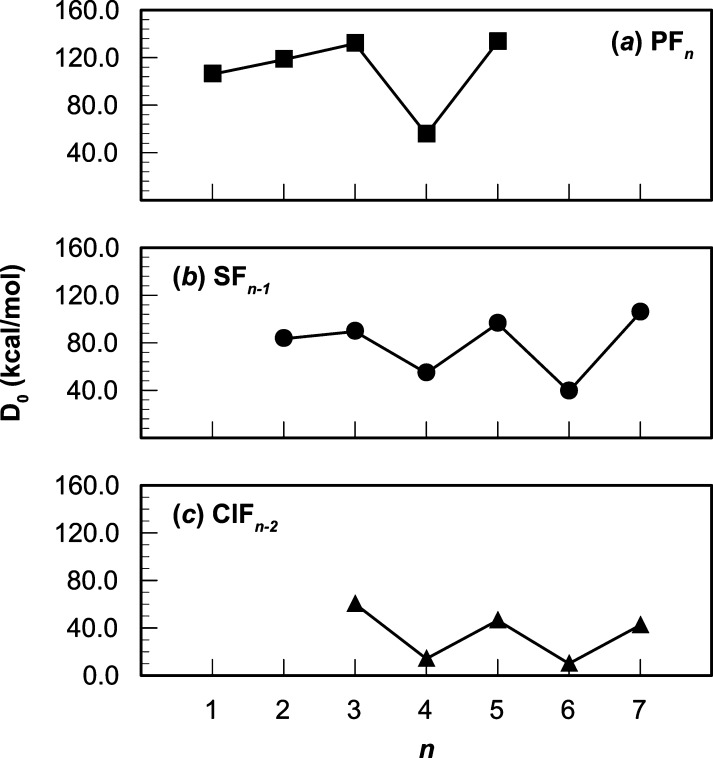

The interplay between covalent and recoupled pair bonding in the halides of the late p-block elements profoundly affects the energetics of these molecules. There is a steady increase in the strength of the covalent bonds until the maximum number of covalent bonds has been formed. The next bond is a recoupled pair bond, with covalent and recoupled pair bonds alternating thereafter. Imposed on the dramatic covalent–recoupled pair bond variations are more subtle variations associated with rearrangements of the bonding pairs caused by the strength of the recoupled pair bond dyad (ala SF3). These trends are illustrated in Figure 11 for PFn, SFn, and ClFn. These same trends have been noted and discussed in terms of adiabatic and diabatic bond energies by Grant et al.32

Figure 11.

Variations in calculated sequential bond energies for the fluorides of P, S, and Cl. Method: [CCSD(T),RCCSD(T)]/aug-cc-pV(Q+d)Z.

4.3. Inversion Pathways

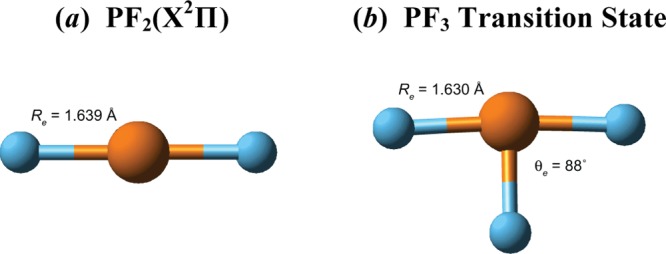

An important process in pyramidal molecules such as ammonia (NH3) is inversion through a planar D3h configuration. In NH3 the barrier is very low (5 kcal/mol). NF3 and PH3 also invert through a D3h structure, although in this case the barriers are quite high.33−35 As reported and validated by Dixon and co-workers,36−38 the saddle point for inversion of PF3 is a planar, T-shaped C2v configuration rather than the D3h transition state found in NH3, NF3, and PH3. The T-shaped transition state in PF3 lies ∼54 kcal/mol above the pyramidal ground state.31

A number of papers have been published attempting to explain the anomalous geometry of the transition state for inversion in PF3 and other molecules.39,40 The reason is now clear—the T-shaped PF3 transition state has a recoupled pair bond dyad,7 thereby avoiding the repulsive interactions associated with the doubly occupied P(3pπ2)-like orbital in the D3h transition state. The F–P–F moiety in the T-shaped transition state is nearly identical to that found in PF2(A2Π), which also has a recoupled bond pair dyad; see Figure 12. The length of the covalent bond in the PF3 transition state, 1.561 Å, differs little from that in the ground state of PF3, 1.567 Å.

Figure 12.

Calculated [CCSD(T)/RCCSD(T)] equilibrium structures of (a) excited 2Π state of PF2 and (b) T-shaped transition state for inversion of PF3. Method: [CCSD(T),RCCSD(T)]/aug-cc-pV(Q+d)Z.

Dixon et al.31 found the transition state for inversion in PF2H also has a planar, T-shaped C2v structure, but the transition states for PH2F and PH3 have D3h-like structures. The only way to form a strong recoupled pair dyad with a late p-block element is with two very electronegative ligands. So, it is possible to form a recoupled pair bond dyad in the transition state of PF2H but not in PH2F or PH3.

4.4. Chemical Reactions

Reactions of compounds of the second row, late p-block elements differ markedly from those of the first row.41 Although the studies reported in ref (41) illustrate the importance of hypervalency in chemical reactions, they provide few detailed insights into the role of recoupled pair bonding in chemical reactivity. Recently, Lu and co-workers42,43 reported molecular beam and computational studies of the reaction of F2 with dimethyl sulfide, (CH3)2S, that have begun to shed light on this question. There are two channels for this reaction:

| 1a |

| 1b |

Reaction 1a occurs at very low energies, indicating a barrierless reaction. Reaction 1b occurs as soon as the energy of the two reactants exceeds the endothermicity of the reaction. This is a most unusual finding for a reaction involving two closed shell molecules. Calculations by Lu and co-workers42,43 showed that the reaction proceeded through a (CH3)2S–F–F intermediate.

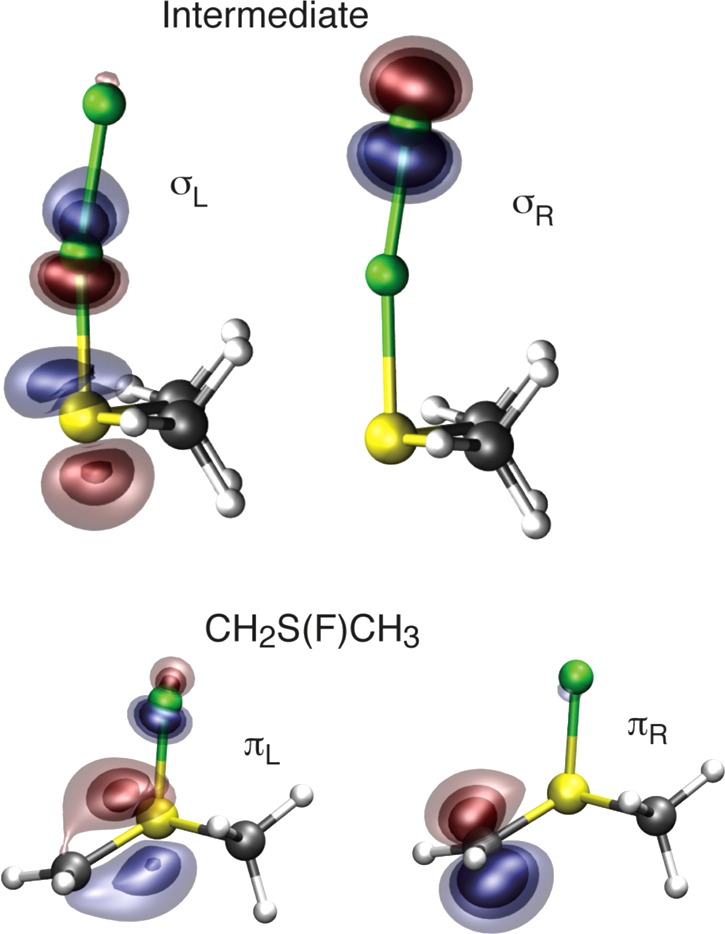

Recoupled pair bonds are key to the (CH3)2S + F2 reaction.44 They account for the stability of the sulfur products, CH2S(F)CH3 and (CH3)2SF, as well as the (CH3)2S–F–F intermediate. The bonding in (CH3)2S–F is straightforward: F forms a recoupled pair bond with one of the sulfur lone pair orbitals. As expected from calculations on the SF*(a4Σ–) state, the SF bond is weak (33.4 kcal/mol) and long (2.00 Å).40−42

Bonding in the (CH3)2S–F–F intermediate and CH2S(F)CH3 product is most unusual. In the intermediate, the bond between the F atoms arises from singlet coupling the electrons in the singly occupied antibonding orbital of (CH3)2SF and the singly occupied orbital on the outer F atom; see Figure 13 (top). The SF antibonding orbital has only a small amplitude on the central F atom. As a result, the overlap between the antibonding orbital and outer F(2p) orbital is very small, S = 0.22, and the resulting F–F bond is very weak (10.9 kcal/mol) and long (1.78 vs 1.41 Å in F2).42,44

Figure 13.

Plots of the SF–F σ bonding orbitals (σL,σR) in the (CH3)2S–F–F intermediate (top) and the CS “π” bonding orbitals (πL,πR) in CH2=S(F)CH3 (bottom).

In the CH2S(F)CH3 product, a ylide, there is a double bond between CH2 and S. The C–S σ bond is a normal covalent bond between carbon and sulfur. The π-like bond, on the other hand, results from singlet coupling the electrons in the singly occupied radical orbital on CH2 and the singly occupied antibonding orbital from the SF recoupled pair bond—see Figure 13 (bottom)—an unusual type of recoupled pair bond dyad. CH2S(F)CH3 is calculated to lie 76–81 kcal/mol below the reactants.40−42,44

5. Conclusions

In this Account, we have shown that the ability of the late p-block elements, specifically, P, S, and Cl, to form recoupled pair bonds and recoupled pair bond dyads with halogens explains many aspects of anomalous behavior of these species. Specifically, these bonds are responsible for:

-

•

Stability of hypervalent molecules. PF4, PF5, SF3, SF4, ClF2, ClF3, and ClF4 have one recoupled pair bond dyad; SF5 and ClF5 have two; and SF6 has three.

-

•

Common structural elements. Recoupled bond pair dyads favor near linear configurations, while covalent bonds favor 90° bond angles. Recoupled pair bonds are much longer than covalent bonds, but the differences are far smaller for dyads.

-

•

Variations in bond energies. Bond strengths increase slightly until the nominal valence is satisfied. Thereafter, recoupled pair and polar covalent bonds alternate—one weak, the other strong.

-

•

Unexpected excited states. Additional bound excited states with recoupled pair bonds are found, even in molecules with normal valence.

-

•

New transition states for inversion. Heavily fluorinated, tricoordinated compounds of late p-block elements invert through a T-shaped transition state, the stability of which is a result of a recoupled pair bond dyad.

-

•

New pathways for chemical reactions. Recoupled pair bonds lead to new pathways for reactions of late p-block compounds with very electronegative reactants.

Although this Account focused on the halides of the second row, late p-block elements, it is clear that recoupled pair bonds are important in the chemistry of p-block elements beyond the second row, for example, As, Se, and Br, as well as in late p-block compounds with other very electronegative ligands, for example, OH and O. Knowledge of recoupled pair bonding is critical to understanding the properties of molecules containing the late p-block elements beyond the first row.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Distinguished Chair for Research Excellence in Chemistry and the National Center for Supercomputing Applications at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. The National Science Foundation provided computing resources for the projects. We thank other students in our research group, Beth Lindquist, Lu Xu and Tyler Takeshita, for valuable insights into and comments on the material presented herein.

Biographies

Thom H. Dunning, Jr. received his B.S. in chemistry from the Missouri University of Science & Technology in 1965 and his Ph.D. in chemistry from the California Institute of Technology in 1970. He currently holds the Distinguished Chair for Research in the Department of Chemistry at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. He is also the director of the National Center for Supercomputing Applications. His current research focuses on the electronic structure of molecules, including molecular structure, spectra, energetics and reactivity, with a particular interest in the chemistry of elements beyond the first row of the periodic chart.

David E. Woon holds a B.S. in Metallurgical Engineering and M.S. and Ph.D. degrees in Physics, all from Michigan Technological University. He is currently a Research Scientist at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. In addition to studying the unexpectedly ubiquitous type of chemical interaction known as recoupled pair bonding, he has been active in the fields of astrochemistry and exobiology for nearly 20 years. The latter builds upon his long-term interests in intermolecular interactions and small molecule properties and reactivity.

Jeff Leiding received his B.S. in Chemistry from the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign in 2004. He began his research in quantum chemistry a year earlier under Professor Todd J. Martinez. He joined Professor Dunning’s research group in 2008 and successfully defended his doctoral thesis in May 2012; he is now a postdoctoral fellow at Los Alamos National Laboratory. Since 2008, his research has focused on bonding and isomerism in the ground and excited states of mixed sulfur and phosphorus halides and the reactions of sulfur compounds with molecular fluorine.

Lina Chen spent a portion of her 3-year postdoctoral fellowship exploring the electronic structures of second-row hypervalent species at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. She obtained her Ph.D. in Chemistry from Boston University, where she focused on developing algorithms for mixed quantum-classical molecular dynamics.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Miessler G. L.; Tarr D. A.. Inorganic Chemistry, 3rd ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Musher J. I. The chemistry of hypervalent molecules. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1969, 8, 54–68. [Google Scholar]

- Kutzelnigg W. Chemical bonding in higher main group elements. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1984, 23, 272–295. [Google Scholar]

- Woon D. E.; Dunning T. H. Jr. A comparison between polar covalent bonding and hypervalent recoupled pair bonding in chalcogen halide species {O,S,Se}×{F,Cl,Br}. Mol. Phys. 2009, 107, 991–998. [Google Scholar]

- Woon D. E.; Dunning T. H. Jr. Theory of Hypervalency: Recoupled pair bonding in SFn (n = 1–6). J. Phys. Chem. A 2009, 113, 7915–7926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L.; Woon D. E.; Dunning T. H. Jr. Bonding in ClFn (n = 1–7) molecules: Further insight into the electronic structure of hypervalent molecules and recoupled pair bonds. J. Phys. Chem. A 2009, 113, 12645–12654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woon D. E.; Dunning T. H. Jr. Recoupled Pair Bonding in PFn (n = 1–5). J. Phys. Chem. A 2010, 114, 8845–8851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiding J; Woon D. E.; Dunning T. H. Jr. Bonding and isomerism in SFn–1Cl (n = 1–6): A quantum chemical study. J. Phys. Chem. A 2011, 115, 329–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiding J.; Woon D. E.; Dunning T. H. Jr. Bonding in SCln (n = 1–6): A quantum chemical study. J. Phys. Chem. A 2011, 115, 4757–4764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woon D. E.; Dunning T. H. Jr. Hypervalency and recoupled pair bonding in the p-block elements. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2011, 963, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Leiding J.; Woon D. E.; Dunning T. H. Jr. Theoretical studies of the excited doublet states of SF and SCl, and singlet states of SF2, SFCl and SCl2. J. Phys. Chem. A 2012, 116, 1655–1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeshita T.; Dunning T. H. Jr. Private communication.

- Goddard W. A. III; Dunning T. H. Jr.; Hunt W. J.; Hay P. J. Generalized valence bond description of bonding in low-lying states of molecules. Acc. Chem. Res. 1973, 6, 368–376. [Google Scholar]

- Goddard W. A. III; Harding L. B. The description of chemical bonding from ab initio calculations. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 1978, 29, 363–396. [Google Scholar]

- Pauling L.Nature of the chemical bond; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Werner H.-J.; Knowles P. J. An efficient internally contract multiconfiguration-reference configuration interaction method. J. Chem. Phys. 1988, 89, 5803–5814. [Google Scholar]

- Ragavachari K.; Trucks G. W.; Pople J. A.; Head-Gordon M. A fifth-order perturbation comparison of electron correlation theories. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1989, 157, 479–483. [Google Scholar]

- Knowles P. J.; Hampel C.; Werner H.-J. Coupled cluster theory for high spin, open shell reference wave functions. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 99, 5219–5227. [Google Scholar]

- Langhoff S. R.; Davidson E. R. Configuration interaction calculations on the nitrogen molecule. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 1974, 8, 61–72. [Google Scholar]

- Dunning T. H. Jr. Gaussian basis sets for use in correlated molecular calculations. I. The atoms boron through neon and hydrogen. J. Chem. Phys. 1989, 90, 1007–1023. [Google Scholar]

- Dunning T. H. Jr.; Peterson K. A.; Wilson A. K. Gaussian basis sets for use in correlated molecular calculations. X. The atoms aluminum through argon revisited. J. Chem. Phys. 2001, 114, 9244–9253. [Google Scholar]

- Gerratt J; Cooper D. L.; Karadakov P. B.; Raimondi M. Modern valence bond theory. Chem. Soc. Rev. 1997, 87–100 and references therein. [Google Scholar]

- Thorsteinsson T.; Cooper D. L.. An overview of the CASVB approach to modern valence bond calculations. In Quantum Systems in Chemistry and Physics. Vol. 1: Basic problems and models systems; Hernández-Laguna A., Maruani J., McWeeny R., Wilson S., Eds.; Kluwer: Dordrecht, 2000; , pp 303–326. [Google Scholar]

- Roos B. O. The complete active space SCF method in a fock-based super-CI formulation. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 1980, S14, 175–189 and references therein. [Google Scholar]

- Ruedenberg K.; Schmidt M. W.; Gilbert M. M.; Elbert S. T. Are atoms intrinsic to molecular electronic wavefunctions?. Chem. Phys. 1982, 71, 41–49and other papers in the series. [Google Scholar]

- Werner H.-J.; Knowles P. J.; Amos R. D.; Bernhardsson A.; Berning A.; Celani P.; Cooper D. L.; Deegan M. J. O.; Dobbyn A. J.; Eckert F.; Hampel C.; Hetzer G.; Korona T.; Lindh R.; Lloyd A. W.; McNicholas S. J.; Manby F. R.; Meyer W.; Mura M. E.; Nicklass A.; Palmieri P.; Pitzer R.; Rauhut G.; Schütz M.; Schumann U.; Stoll H.; Stone A. J.; Tarroni R.; Thorsteinsson T.. Molpro, version 2009.1; University College Cardiff Consultants Ltd.: Cardiff, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- For comparison to the experimental data, which is excellent, see refs (4−11).

- Pimentel G. C. The bonding of trihalide and bifluoride ions by molecular orbital theory. J. Chem. Phys. 1951, 19, 446–448. [Google Scholar]; Rundle R. E. On the probable structure of XeF2 and XeF4. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1949, 85, 112–113. [Google Scholar]

- Ponec R.; Yuzhakov G.; Cooper D. L. Multicenter bonding and the structure of electron-rich molecules. Model of three-center four-electron bonding reconsidered. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2004, 112, 419–430. [Google Scholar]

- McGrady G. S.; Steed J. W.. Hypervalent compounds. In Encyclopedia of Inorganic Chemistry 2; King R. B., Ed.; John Wiley and Sons: Chichester, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Schleyer P. v. R. Hypervalent compounds. Chem. Eng. News 1984, 62, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Grant D. J.; Matus M. H.; Dixon D. A.; Francisco J. S.; Christe K. O. Bond dissociation energies in second row compounds. J. Phys. Chem. A 2008, 112, 3145–3156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon D. A; Arduengo A. J. III. Periodic trends in the edge and vertex inversion barriers for tricooridinate pnictogen hydrides and fluorides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987, 109, 338–341. [Google Scholar]

- Schmiedekamp A.; Skaarup S.; Pulay P.; Boggs J. E. Ab initio investigation of geometry changes during inversion of NH3, NH2F, NHF2, NF3 and PH3, PH2F, PHF2, PF3. J. Chem. Phys. 1977, 66, 5769–5776. [Google Scholar]

- Marynick D. S. The inversion barriers of NF3, NCl3, PF3 and PCl3. A theoretical study. J. Chem. Phys. 1980, 73, 3939–3943. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon D. A.; Arduengo A. J. III; Fukunaga T. A new inversion process at Group VA (Group 15) elements. Edge inversion through a planar T-shaped structure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986, 108, 2461–2462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arduengo A. J. III; Dixon D. A.; Roe D. C. Direct determination of the barrier to edge inversion at trivalent phosphorus. Verification of the edge inversion mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986, 108, 6821–6823. [Google Scholar]

- Arduengo A. J. III; Stewart C. A.; Davidson F.; Dixon D. A.; Becker J. Y.; Culley S. A.; Mizen M. B. The synthesis, structure and chemistry of 10-Pn-3 systems: Tricoordinate hypervalent pnictogen compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987, 109, 627. [Google Scholar]

- Edgecombe K. E. A topological electron density analysis of tricoordinate phosphorus inversion process. J. Mol. Struct.: THEOCHEM 1991, 226, 157–179. [Google Scholar]

- Creve S.; Nguyen M. T. Inversion processes in phosphines and their radical cations: When is a pseudo-Jahn-Teller effect operative?. J. Phys. Chem. A 1998, 102, 6549–6557. [Google Scholar]

- Akiba K., Ed. Chemistry of Hypervalent Compounds; Wiley-VCH: New York, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y.-J.; Lee L.; Pan J.-W.; Witek H. A. Dynamics of the F2 + CH3SCH3 reaction: A molecule-molecule reaction without entrance barrier. J. Chem. Phys. 2007, 127, 101101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y.-J.; Lee L.; Pan J.-W.; Xie T.; Witek H. A.; Lin J. J. Barrierless reactions between two closed-shell molecules. I. Dynamics of F2 + CH3SCH3 reaction. J. Chem. Phys. 2008, 128, 104317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiding J. A.; Woon D. E.; Dunning T. H. Jr. Insights into the unusual barrierless reaction between two closed shell molecules, (CH3)2S + F2, and its H2S + F2 analogue: Role of recoupled pair bonding. J. Phys. Chem. A 2012, 116, 5247–5255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]