Abstract

Purpose

To compare the efficacy of chemoendocrine treatment with that of endocrine treatment (ET) alone for postmenopausal women with highly endocrine responsive breast cancer.

Patients and methods

In the International Breast Cancer Study Group (IBCSG) Trials VII and 12-93, postmenopausal women with node-positive, estrogen receptor (ER)-positive or ER-negative, operable breast cancer were randomized to receive either chemotherapy or endocrine therapy or combined chemoendocrine treatment. Results were analyzed overall in the cohort of 893 patients with endocrine-responsive disease, and according to prospectively-defined categories of ER, age and nodal status. STEPP analyses assessed chemotherapy effect. The median follow-up was 13 years.

Results

Adding chemotherapy reduced the relative risk of a disease-free survival event by 19% (p=0.02) compared with ET alone. STEPP analyses showed little effect of chemotherapy for tumors with high levels of ER expression (p = 0.07), or for the cohort with one positive node (p = 0.03).

Conclusions

Chemotherapy significantly improves disease-free survival for postmenopausal women with endocrine-responsive breast cancer, but the magnitude of the effect is substantially attenuated if ER levels are high.

Keywords: breast cancer, chemoendocrine therapy, estrogen receptors, postmenopausal

Introduction

Targeted therapies are recognized as the appropriate modern strategy for the treatment of early breast cancer. The definition of endocrine responsiveness was further refined during the 2007 St Gallen International Expert Consensus on the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer: highly endocrine-responsive tumors (previously referred to as endocrine responsive) express high levels of both steroid hormone receptors in the majority of cells (assessed by proper immunohistological methods), whereas incompletely endocrine responsive (previously referred to as endocrine response uncertain) show some expression of steroid hormone receptors, but at lower levels or lacking either estrogen receptor (ER) or progesterone receptor (PgR) (1). In the 2005 Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) meta-analysis, on average, a significant proportional reduction in recurrence and mortality due to chemotherapy was shown, irrespective of endocrine responsiveness, age, nodal status and regimen given (2).

Nevertheless, the extra benefit of adding chemotherapy to effective endocrine treatment (ET) is still a matter of debate (3, 4). Several randomized trials have reported a favorable impact of adjuvant chemotherapy in addition to tamoxifen (TAM) alone in postmenopausal women with node-positive and endocrine-responsive breast cancer (5–8), but few reports are available in the subgroup of patients whose tumors express high levels of estrogen receptors (ER) (9). Retrospective, exploratory analyses of the Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG) protocol 8814 (Intergroup 0100 trial) in postmenopausal patients with node-positive breast cancer suggest that the extra benefit from adding combination chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin and fluorouracil (CAF) to TAM alone was essentially confined to patients with low and intermediate levels of ER expression, while no benefit from CAF was seen for patients with 1–3 positive axillary nodes, and for patients with high levels of ER in their primary tumors (10). The chemotherapy benefit might not be large enough for patients with highly endocrine-responsive tumors to justify the routine use of chemotherapy.

The International Breast Cancer Study Group (IBCSG) Trials VII and 12-93 evaluated chemoendocrine therapy compared with ET alone in peri- and postmenopausal women with node-positive operable breast cancer. The results of these trials have been previously reported (11–13). In the present paper we analyze the influence on disease-free survival (DFS) of adding chemotherapy to ET for patients with ER-positive disease, and examine the relationship between the magnitude of treatment effect and the level of ER expression in the primary tumor.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Design

Trials VII and 12-93 are randomized multicenter clinical trials designed and conducted by IBCSG for patients with node-positive breast cancer. Between 1986 and 1993 Trial VII randomized postmenopausal patients with either ER-positive or ER-negative primary tumors to one of four treatment groups: TAM alone for 5 years, TAM plus three courses of early cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil (CMF) on months 1, 2, and 3 (early CMF plus TAM), TAM plus delayed single courses of CMF on months 9, 12, and 15 (delayed CMF plus TAM), TAM plus early and delayed CMF on months 1, 2, 3, 9, 12, and 15 (early plus delayed CMF plus TAM). Early chemotherapy started on the same day as TAM (11). Between 1993 and 1999 Trial 12-93 randomized peri- and postmenopausal patients (hereafter referred to as postmenopausal) with ER-positive primary tumors to TAM or Toremifene (TOR) and to one of three systemic therapy regimens: chemotherapy (four courses of AC [anthracycline (doxorubicin or epirubicin) plus cyclophosphamide]) with concomitant ET, chemotherapy with sequential ET, and ET alone. In 1997 the three-arm randomization for the chemotherapy-oriented question was discontinued due to insufficient accrual and the trial continued with only the TOR versus TAM randomization; the use and type of chemotherapy prior to initiation of the endocrine treatment was left to the discretion of the investigators (13). Institutional review boards reviewed and approved the protocols, and informed consent was required according to the criteria established within the individual countries.

Patient Characteristics

A total of 1266 patients with pathologically confirmed early breast cancer and axillary nodal involvement were accrued in Trial VII and 452 in Trial 12-93. The present analysis includes 686 patients from Trial VII with ER-positive disease randomized to TAM, early CMF plus TAM or early plus delayed CMF plus TAM and 207 peri and postmenopausal patients with ER-positive tumors in the original three-arm randomization option in Trial 12-93. The median follow-up of the combined study cohort of 893 patients was 13 years; 14.8 years for Trial VII and 10.0 years for Trial 12-93. The patient and tumor characteristics of the study cohort are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

IBCSG Trials VII and 12-93 patient and tumor characteristics

| Trial VII | Trial 12-93 | Combined | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Randomized | 1266 | 100 | 452 | 100 | 1718 | 100 |

| Study Cohort (all ER-positive) a | 686 | 54 | 207 | 46 | 893 | 52 |

| Highly ER+ | 479 | 70 | 167 | 81 | 646 | 72 |

| Low-intermediate ER+ | 207 | 30 | 40 | 19 | 247 | 28 |

| Chemoendocrine | 450 | 66 | 139 | 67 | 589 | 66 |

| Endocrine alone | 236 | 34 | 68 | 33 | 304 | 34 |

| Age <60 years | 292 | 43 | 117 | 57 | 409 | 46 |

| Age ≥60 years | 394 | 57 | 90 | 43 | 484 | 54 |

| 1–3 positive nodes | 430 | 63 | 171 | 83 | 601 | 67 |

| ≥ 4 positive nodes | 256 | 37 | 36 | 17 | 292 | 33 |

Includes the ER-positive cohort enrolled in 3 of the 4 treatment groups in Trial VII or enrolled in the ”chemotherapy randomization” of the original Trial 12-93 design.

Abbreviations: ER: estrogen receptor

Patients were enrolled after primary surgery, which consisted either of a total mastectomy or breast conserving procedure with breast irradiation, and axillary clearance. Patients with clinical stages T1 to T3 N1 M0 (International Union Against Cancer [UICC] 1987 classification) were considered eligible. Pre-randomization studies included hematological evaluation, renal and liver function tests, chest X-ray and bone scan. ER extraction assays of the primary tumor were considered positive if levels of cytosol protein were 10 or more fmol/mg of tissue cytosol. Most ER results were reported from extraction assays (766 patients), but, as immunohistochemistry (IHC) methods started to be used in the mid-1990s, some results were reported as categorical IHC (expressed as negative, borderline positive, positive, or strongly positive) (50 patients), or quantitative IHC (% positive immunostained cells) (77 patients). For the purpose of the present analysis, the category of highly ER-positive disease (as distinct from the low-intermediate ER category) was defined prior to data analysis as greater than 50% positive cells by quantitative IHC, strongly positive by qualitative IHC, or levels of cytosol protein ≥ 50 fmol/mg cytosol protein by extraction assay.

Statistical Methods

Disease-free survival (DFS) was defined as the length of time from the date of randomization to any relapse (including ipsilateral breast recurrence), the appearance of a second primary (including contralateral breast cancer) or death, whichever occurred first. DFS percentages, standard errors and treatment effect comparisons were obtained from the Kaplan-Meier method (14), Greenwood’s formula (15), and log-rank tests (16), respectively. The log-rank test for the combined cohort was stratified by the individual trials.

Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for chemotherapy treatment effect were estimated from Cox proportional hazards models (17) overall and for prospectively defined subgroup categories of ER (highly ER positive versus low-intermediate ER positive), age (less than 60 years versus 60 years and older), and nodal status (1–3 positive nodes versus 4 or more positive nodes). P-values are not reported for these subgroup analyses, which should rely on the estimated hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals to assess variations in chemotherapy effect relative to the effect observed for the entire cohort (18).

The non-parametric subpopulation treatment effect pattern plot (STEPP) methodology (19, 20) was used to further explore the trends in treatment effect differences according to ER levels (limited to the 766 patients with extraction assay values), age (in years) and nodal involvement (number of positive nodes). STEPP involves defining several overlapping subgroups of patients on the basis of a covariate of interest and studying the resulting pattern of the treatment effects estimated within each subgroup.

RESULTS

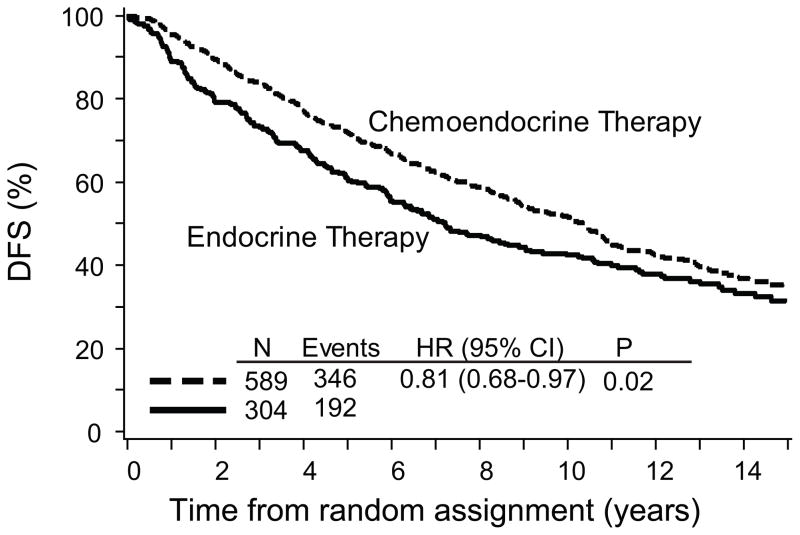

Overall, patients who received chemoendocrine therapy had improved DFS compared with patients who received ET alone (TAM or TOR) (HR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.68 to 0.97; p=0.02) (Table 2) as shown in Figure 1. The estimated overall reduction in the relative risk of a DFS event was 19%. The addition of chemotherapy provided a DFS advantage regardless of the Trial (VII or 12-93), ER category (highly ER-positive or low-intermediate ER-positive) (Table 2), age category (less than 60 or 60 years and older), nodal status category (3 or fewer versus 4 or more) (Table 3). The risk of a DFS event was reduced by 22% and 17% in women less than 60 years and 60 years and older, respectively and by 11% and 31% in patients with 3 or fewer or 4 or more positive nodes (Table 3).

Table 2.

Study Cohort (ER+) DFS according to treatment group

| Total N° | Events | HR a (CT/No CT) (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trials VII and 12-93: | |||

| Chemoendocrine | 589 | 346 | 0.81 (0.68, 0.97) |

| Endocrine alone | 304 | 192 | |

| Trial VII | |||

| Chemoendocrine | 450 | 291 | 0.86 (0.70, 1.04) |

| Endocrine alone | 236 | 158 | |

| Trial 12-93 | |||

| Chemoendocrine | 139 | 55 | 0.63 (0.41, 0.97) |

| Endocrine alone | 68 | 34 | |

| Trials VII and 12-93: | |||

| Highly ER+ | |||

| Chemoendocrine | 428 | 248 | 0.79 (0.64, 0.97) |

| Endocrine alone | 218 | 140 | |

| Trial VII: | |||

| Highly ER+ | |||

| Chemoendocrine | 318 | 205 | 0.86 (0.68, 1.09) |

| Endocrine alone | 161 | 109 | |

| Trial 12-93: | |||

| Highly ER+ | |||

| Chemoendocrine | 110 | 43 | 0.54 (0.34, 0.86) |

| Endocrine alone | 57 | 31 | |

| Trials VII and 12-93: | |||

| Low-intermediate ER+ | |||

| Chemoendocrine | 161 | 98 | 0.89 (0.64, 1.25) |

| Endocrine alone | 86 | 52 | |

| Trial VII: | |||

| Low-intermediate ER+ | |||

| Chemoendocrine | 132 | 86 | 0.84 (0.59, 1.19) |

| Endocrine alone | 75 | 49 | |

| Trial 12-93: | |||

| Low-intermediate ER+ | |||

| Chemoendocrine | 29 | 12 | 1.70 (0.48, 6.04) |

| Endocrine alone | 11 | 3 | |

Hazard ratios (HR) are stratified by trial where appropriate

Abbreviations: CT: chemotherapy; ER: estrogen receptor

Fig 1.

Kaplan-Meier plot of disease-free survival (DFS) for chemoendocrine versus endocrine therapy alone in postmenopausal patients with node-positive, estrogen receptor-positive early breast cancer. The median follow-up is 13 years. Abbreviations: HR=hazard ratio, CI=confidence interval, P=stratified logrank p-value

Table 3.

Study Cohort (ER+) DFS according to treatment group for age and number of positive nodes subgroups

| Trials VII and 12-93: | Total N° | Events | HR a (CT/No CT) (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| <60 years | |||

| Chemoendocrine | 277 | 151 | 0.78 (0.59, 1.02) |

| Endocrine alone | 132 | 79 | |

| ≥ 60 years | |||

| Chemoendocrine | 312 | 195 | 0.83 (0.66, 1.05) |

| Endocrine alone | 172 | 113 | |

| 1–3 positive nodes | |||

| Chemoendocrine | 402 | 207 | 0.89 (0.70, 1.12) |

| Endocrine alone | 199 | 108 | |

| ≥ 4 positive nodes | |||

| Chemoendocrine | 187 | 139 | 0.69 (0.53, 0.91) |

| Endocrine alone | 105 | 84 | |

Hazard ratios (HR) are stratified by trial

Abbreviations: CT: chemotherapy; ER: estrogen receptor

Within each trial, the addition of early or early plus delayed CMF in Trial VII and of early AC in Trial 12-93, as compared with ET alone, resulted in a 14% and 37% reduction in the risk of a DFS event, respectively (Table 2). Adjuvant TAM and TOR, as previously reported, showed similar efficacy, in terms of DFS and overall survival (OS), and comparable toxicity in postmenopausal patients with node-positive breast cancer (13). Although there was no difference between the DFS for the small number of women who received sequential chemo-endocrine therapy (66 patients) and those who received concurrent chemo-endocrine therapy (73 patients) in Trial 12-93, we cannot rule out a potential detrimental effect of concurrent treatment for the entire trial population (HR (concurrent/sequential),1.07; 95% CI, 0.63 to 1.82; p=0.80).

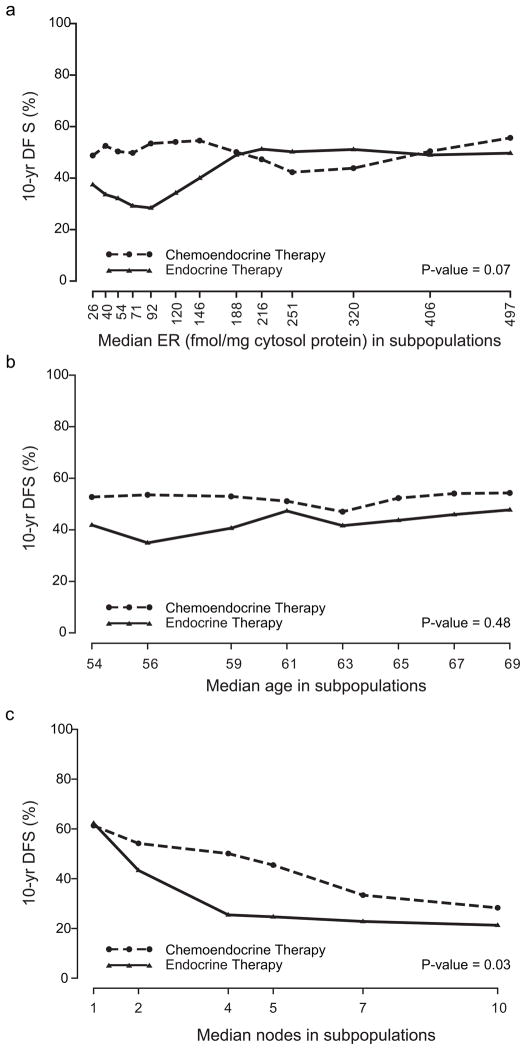

STEPP analyses were used to explore the pattern of treatment effect differences in terms of 10-year DFS according to quantitative levels of ER of the primary tumor, patient age and number of involved nodes (Figure 2a–c). For these sliding window analyses, each subpopulation contained approximately 200 patients total for both the chemo-endocrine and endocrine subgroups, and each subsequent subpopulation was formed moving from left to right by dropping approximately 50 patients with the lowest covariate values and adding approximately 50 patients with the next higher covariate value. The X coordinate indicates the median covariate values for the patients in each subpopulation. The Y coordinate indicates the 10-year DFS percent estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method on data from patients in each subpopulation.

Fig 2.

Subpopulation Treatment Effect Pattern Plots (STEPP) of 10-year disease-free survival (DFS) (%) according to: a) quantitative ER values (fmol/mg cytosol protein) of the primary tumor, b) patient age in years and c) number of involved axillary lymph nodes

Figure 2a shows the STEPP analysis according to quantitative values of ER: a benefit of adding chemotherapy to ET is clearly evident for the low through intermediate values of ER. When the ER expression values are quite high (greater than 188 fmol/mg cytosol protein, representing 334 of the 809 women with available extraction assays), the 10-year DFS achieved by ET alone reaches the level achieved by the chemoendocrine combination. Figures 2b and c show the STEPP analyses according to age and nodal involvement: the extra benefit of chemotherapy appears to be slightly greater in younger postmenopausal women (less than 60 years) and in patients with high risk disease (more than 3 positive nodes) with no difference observed for patients with one positive axillary lymph node.

DISCUSSION

Overall, the addition of adjuvant chemotherapy to endocrine therapy improved disease-free survival on average for postmenopausal women with node-positive, ER-positive breast cancer. The addition of chemotherapy improved outcome irrespective of prospectively-defined nodal status category, age category, or category of ER expression. However, STEPP analyses of treatment outcome according to continuous measures of number of positive nodes, age, and extraction assay ER values suggest that the magnitude of chemotherapy benefit may differ in predictable ways for patient subgroups within the larger cohort of postmenopausal women with node-positive, ER-positive disease. In particular, patients with tumours expressing very high levels of ER, and those with only one positive axillary lymph node appeared to benefit little from adding chemotherapy to endocrine therapy. STEPP provides exploratory analyses designed to complement the overall results and to suggest areas for further investigation and confirmation in other datasets.

Reduced effectiveness of the addition of chemotherapy to endocrine therapy for high levels of ER expression among postmenopausal women has also been observed in other trials (9, 10). As stressed in the 2007 St. Gallen recommendations (1), one of the most difficult challenges in treating early breast cancer is selecting those patients with highly or incompletely endocrine-responsive disease who should receive chemoendocrine treatment.

Accurate assessment of steroid hormone receptor concentrations in the primary tumors remains a challenge. Up to a 30% discordance has been reported between IHC and extraction steroid hormone assessment (21), and IHC has been associated with a superior predictive and prognostic value in several studies (22). A recent retrospective central laboratory review of specimens from IBCSG Trial IX (a randomized comparison of adjuvant chemoendocrine therapy versus endocrine therapy alone for postmenopausal women with node-negative disease) showed 80% concordance of ER status as determined by central IHC or local extraction assay, although the trial conclusions according to ER status remained the same regardless of the method used (23).

Endocrine therapy alone is possibly not as effective for patients with low-intermediate ER levels as it is for high levels of ER expression. Alternatively, chemosensitive targets play a more important role in less endocrine-responsive tumors. Aromatase inhibitors (AIs) have been shown to provide additional DFS benefit compared with tamoxifen for postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer (24, 25). In a recent report of centrally-reviewed estrogen receptors by immunohistochemistry in the BIG1-98 trial comparing tamoxifen to the aromatase inhibitor letrozole, no clear statistical evidence of differential treatment effect according to ER expression was observed (26).

Biological co-factors in addition to level of ER expression are quite likely to influence the magnitude of chemotherapy benefit. A recent exploratory STEPP analysis of PgR levels (PgR less than 10 and PgR 10 and greater fmol/mg cytosol protein) in IBCSG Trial VII reported a benefit from adjuvant CMF especially in tumors with intermediate levels of ER, but low levels of PgR (9). These findings should be viewed as hypothesis generating, as understanding the influence of other potential chemosensitive biological targets, e.g. luminal B subtypes, HER2 overexpression/amplification and/or measures of proliferation, could be helpful to further tailor the addition of chemotherapy within this otherwise endocrine-responsive cohort. Molecular signatures of gene expression able to distinguish patients with low- and high-risk disease in node-negative breast cancer have been identified (27) and studies suggest a predictive role in high risk women (more than 10 positive nodes) as well (28). High levels of ER defined by Allred Score (10) as well as low recurrence score values based on OncoType Dx (29) are indicators of little benefit of adding anthracycline-based chemotherapy to endocrine therapy for postmenopausal women with node-positive disease enrolled in the INT 0100/SWOG 8841 trial. The results of ongoing multi-institutional, randomized trials in North America (TAILOR-X) (30) and Europe (MINDACT) (31) may assist in better identifying patients with endocrine-responsive tumors who would likely benefit from chemo-endocrine adjuvant strategies.

The 2005 EBCTCG Overview, which normally presents results primarily according to age (under 50 and 50 to 69 years of age), showed a substantial benefit of chemoendocrine treatment compared with tamoxifen alone for women less than 50 years with ER-positive tumors, whereas the magnitude of benefit was not as substantial for women 50 years of age and older with ER-positive disease (2). Since age is not a therapeutic target and many women in their fifties maintain some degree of ovarian function, our STEPP analysis suggesting a somewhat larger impact of chemotherapy in younger postmenopausal women (less than 60 years) could partially be explained by a persistent endocrine effect of cytotoxics. In any case, there is no evidence that age per se should be used as a factor to determine whether or not chemotherapy would be beneficial for women with breast cancer. In particular, for premenopausal women with endocrine responsive breast cancer who receive adequate endocrine treatment, the role of chemotherapy remains uncertain (32, 33).

Four courses of AC or six courses of classical CMF are generally considered suitable in patients with highly or incompletely endocrine-responsive disease, and a recent review of the Cancer and Leukemia Group B trials suggested that the benefits of “more intensive” compared with ”standard dose” chemotherapy were negligible for women with node-positive, ER-positive cancers (4). Nevertheless, current chemotherapy regimens including more effective use of anthracyclines and taxanes may yield results that differ from those reported here.

Our analyses confirm that on average adding chemotherapy (CMF or AC) to endocrine therapy improves disease-free survival for postmenopausal women with ER-positive, node-positive breast cancer. In general, this could reflect the heterogeneity of tumor cells with a few, highly chemo sensitive ER negative cells, contributing to the additional benefit of chemotherapy. STEPP analyses suggest that the magnitude of this benefit may be less for patients with high levels of ER in the primary tumor, a single positive axillary lymph node, or older women. These results stress the importance of a precise identification and analysis of biological targets to better tailor individual treatment strategies and further improve outcome for women with early breast cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients, physicians, nurses, and data managers who have participated in the International Breast Cancer Study Group (see Appendix) trials, now and for the past 30 years. The IBCSG is funded in part by: Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research (SAKK), Frontier Science and Technology Research Foundation (FSTRF), The Cancer Council Australia, Australian New Zealand Breast Cancer Trials Group (National Health Medical Research Council), National Cancer Institute (CA-75362), Swedish Cancer Society, Cancer Research Switzerland/Oncosuisse, Cancer Association of South Africa, Foundation for Clinical Cancer Research of Eastern Switzerland (OSKK).

Contributor Information

Olivia Pagani, Email: olivia.pagani@ibcsg.org, Oncology Institute of Southern Switzerland, Ospedale Italiano, Viganello, Lugano, Switzerland and Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research (SAKK), Bern, Switzerland.

Shari Gelber, Email: shari@jimmy.harvard.edu, IBCSG Statistical Center, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Frontier Science and Technology Research Foundation, Boston, MA, USA.

Edda Simoncini, Email: bscivile@ns.numerica.it, Oncologia Medica-Spedali Civili, Brescia, Italy.

Monica Castiglione-Gertsch, Email: monica.castiglione@ibcsg.org, IBCSG Coordinating Center, Bern, Switzerland.

Karen N. Price, Email: price@jimmy.harvard.edu, IBCSG Statistical Center and Frontier Science and Technology Research Foundation, Boston, MA, USA

Richard D. Gelber, Email: gelber@jimmy.harvard.edu, IBCSG Statistical Center, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Frontier Science and Technology Research Foundation, Boston, MA, USA

Stig B. Holmberg, Email: stig.holmberg@vgregion.se, Department of Surgery, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Göteborg, Sweden

Diana Crivellari, Email: dcrivellari@cro.it, Centro di Riferimento Oncologico, Aviano, Italy.

John Collins, Email: johncol@bigpond.net.au, Department of Surgery, The Royal Melbourne Hospital, Melbourne, Australia.

Jurij Lindtner, Email: JLindtner@onko-i.si, The Institute of Oncology, Ljubljana, Slovenia.

Beat Thürlimann, Email: beat.thuerlimann@kssg.ch, Senology Center of Eastern Switzerland, Kantonsspital, St. Gallen, Switzerland, Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research (SAKK).

Martin F. Fey, Email: martin.fey@insel.ch, Department of Medical Oncology, Inselspital, Bern, Switzerland, Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research (SAKK)

Elizabeth Murray, Email: Elizabeth.Murray@uct.ac.za, Groote Shuur Hospital and University of Cape Town, South Africa.

John F. Forbes, Email: john.forbes@anzbctg.newcastle.edu.au, Australian New Zealand Breast Cancer Trials Group, University of Newcastle, Calvary Mater Newcastle, Newcastle, New South Wales, Australia

Alan S. Coates, Email: alan.coates@ibcsg.org, International Breast Cancer Study Group, Bern, Switzerland and University of Sydney, Australia

Aron Goldhirsch, Email: aron.goldhirsch@ibcsg.org, Department of Medicine, European Institute of Oncology, Milan, Italy and Oncology Institute of Southern Switzerland, Bellinzona, Switzerland.

References

- 1.Goldhirsch A, Wood WC, Gelber RD, et al. Progress and promise: highlights of the international expert consensus on the primary therapy of early breast cancer 2007. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:1133–1144. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group. Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet. 2005;365:1687–1717. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66544-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldhirsch A, Coates AS, Gelber RD, et al. First select the target: better choice of adjuvant treatments for breast cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:1772–1776. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berry DA, Cirrincione C, Henderson IC, et al. Estrogen-receptor status and outcomes of modern chemotherapy for patients with node-positive breast cancer. JAMA. 2006;295:1658–1667. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.14.1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crivellari D, Bonetti M, Castiglione-Gertsch M, et al. Burdens and benefits of adjuvant cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil and tamoxifen for elderly patients with breast cancer: the International Breast Cancer Study Group trial VII. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:1412–1422. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.7.1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Namer M, Fargeot P, Roché H, et al. Improved disease-free survival with epirubicin-based chemoendocrine adjuvant therapy compared with tamoxifen alone in one to three node-positive, estrogen-receptor-positive, postmenopausal breast cancer patients: results of French Adjuvant Study Group 02 and 07 trials. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:65–73. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdj022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wils JA, Bliss JM, Coombes MG, et al. Epirubicin plus tamoxifen versus tamoxifen alone in node-positive post menopausal patients with breast cancer: a randomized trial of the International Collaborative Cancer Group. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1988–1998. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.7.1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rivkin SE, Green S, Metch B, et al. Adjuvant CMFVP Versus Tamoxifen Versus Concurrent CMFVP and Tamoxifen for Postmenopausal, Node-Positive, and Estrogen Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer Patients: A Southwest Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:2078–2085. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.10.2078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Regan MM, Gelber RD. Predicting response to systemic treatments: learning from the past to plan for the future. The Breast. 2005;14:582–593. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2005.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Albain K, Barlow W, O’Malley F, et al. Concurrent (CAFT) versus sequential (CAF-T) chemohormonal therapy (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, 5-fluorouracil, tamoxifen) versus T alone for postmenopausal, node-positive, estrogen (ER) and/or progesterone (PgR) receptor-positive breast cancer: Mature outcomes and new biologic correlates on phase III intergroup trial 0100 (SWOG-8814) Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2004;88:abstr 37. [Google Scholar]

- 11.The International Breast Cancer Study Group. Effectiveness of adjuvant chemotherapy in combination with tamoxifen for node-positive postmenopausal breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:1385–1393. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.4.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colleoni M, Li S, Gelber RD, et al. Timing of CMF chemotherapy in combination with tamoxifen in postmenopausal women with breast cancer: role of endocrine responsiveness of the tumor. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:716–725. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.International Breast Cancer Study Group. Toremifene and tamoxifen are equally effective for early-stage breast cancer: first results of International Breast Cancer Study Group Trials 12-93 and 14-93. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:1749–1759. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenwood M. The Natural Duration of Cancer. London, UK: Her Majesty’s Stationary Office; 1926. pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mantel N. Evaluation of survival data and two new rank order statistics arising in its consideration. Cancer Chemother Rep. 1966;50:163–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cox DR. Regression models and life-tables (with discussion) J Royal Stat Soc. 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cuzick J. Forest plots and the interpretation of subgroups. Lancet. 2005;365:1308. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)61026-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonetti M, Gelber RD. A graphical method to assess treatment-covariate interactions using the Cox model on subsets of the data. Stat Med. 2000;19:2595–2609. doi: 10.1002/1097-0258(20001015)19:19<2595::aid-sim562>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bonetti M, Gelber RD. Patterns of treatment effects in subsets of patients in clinical trials. Biostatistics. 2004;5:465–481. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/5.3.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chebil G, Bendahl P-O, Idvall I, Ferno M. Comparison of immunohistochemical and biochemical assay of steroid receptors in primary breast cancer. Acta Oncol. 2003;42:719–725. doi: 10.1080/02841860310004724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harvey JM, Clark GM, Osborne CK, Allred DC. Estrogen receptor status by immunohistochemistry is superior to the ligand-binding assay for predicting response to adjuvant endocrine therapy in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1474–1481. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.5.1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Regan MM, Viale G, Mastropasqua MG, et al. Re-evaluating adjuvant breast cancer trials: Assessing hormone receptor status by immunohistochemical versus extraction assays. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1571–1581. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coates AS, Keshaviah A, Thürlimann B, et al. Five Years of Letrozole Compared With Tamoxifen As Initial Adjuvant Therapy for Postmenopausal Women With Endocrine-Responsive Early Breast Cancer: Update of Study BIG 1-98. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:486–492. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.8617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Howell A, Cuzick J, Baum M, et al. Results of the ATAC (Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination) trial after completion of 5 years’ adjuvant treatment for breast cancer. Lancet. 2005;365:60–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17666-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Viale G, Regan MM, Maiorano E, et al. Prognostic and Predictive Value of Centrally Reviewed Expression of Estrogen and Progesterone Receptors in a Randomized Trial Comparing Letrozole and Tamoxifen Adjuvant Therapy for Postmenopausal Early Breast Cancer: BIG 1-98. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3846–3852. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.9453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van’t Veer LJ, Paik S, Hayes DF. Gene expression profiling of breast cancer: A new tumor marker. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1631–1635. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cobleigh MA, Tabesh B, Bitterman P, et al. Tumor Gene Expression and Prognosis in Breast Cancer Patients with 10 or More Positive Lymph Nodes. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:8623–8631. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Albain K, Barlow W, Shak S, et al. Prognostic and predictive value of the 21-gene recurrence score assay in postmenopausal, node-positive, ER-positive breast cancer (S8814, INT0100) [Accessed 02 Jan 2008];San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium 2007 late breaker abstract #. 2008 :10. http://www.abstracts2view.com/sabcs/view.php?nu=SABCS07L_1165.

- 30.Sparano JA. TAILORx: trial assigning individualized options for treatment (Rx) Clin Breast Cancer. 2006;7:347–350. doi: 10.3816/CBC.2006.n.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bogaerts J, Cardoso F, Buyse M, et al. Gene signature evaluation as a prognostic tool: challenges in the design of the MINDACT trial. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2006;3:540–551. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thürlimann B, Price KN, Gelber RD, et al. Is chemotherapy necessary for premenopausal women with lower-risk node-positive, endocrine responsive breast cancer? 10-year update of International Breast Cancer Study Group Trial 11-93. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008 Feb 8;2008 doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-9912-9. Epub ahead of press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Regan MM, Pagani O, Walley B, et al. for the SOFT/TEXT/PERCHE Steering Committee and the International Breast Cancer Study Group. Premenopausal endocrine-responsive early breast cancer: Who receives chemotherapy? Ann Oncol. 2008 Mar 6;2008 doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn037. Epub ahead of press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.