Abstract

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is a severe muscle disease caused by mutations in the DMD gene, with loss of its gene product, dystrophin. Dystrophin helps link integral membrane proteins to the actin cytoskeleton and stabilizes the sarcolemma during muscle activity. We investigated an alternative therapeutic approach to dystrophin replacement by overexpressing human α7 integrin (ITGA7) using adeno-associated virus (AAV) delivery. ITGA7 is a laminin receptor in skeletal and cardiac muscle that links the extracellular matrix (ECM) to the actin skeleton. It is modestly upregulated in DMD muscle and has been proposed to be an important modifier of dystrophic symptoms. We delivered rAAV8.MCK.ITGA7 to the lower limb of mdx mice through isolated limb perfusion (ILP) of the femoral artery. We demonstrated ~50% of fibers in the tibialis anterior (TA) and extensor digitorum longus (EDL) overexpressing α7 integrin at the sarcolemma following AAV gene transfer. The increase in ITGA7 in skeletal muscle significantly protected against loss of force following eccentric contraction-induced injury compared with untreated (contralateral) muscles while specific force following tetanic contraction was unchanged. Reversal of additional dystrophic features included reduced Evans blue dye (EBD) uptake and increased muscle fiber diameter. Taken together, this data shows that rAAV8.MCK.ITGA7 gene transfer stabilizes the sarcolemma potentially preserving mdx muscle from further damage. This therapeutic approach demonstrates promise as a viable treatment for DMD with further implications for other forms of muscular dystrophy.

Introduction

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is the most common, severe childhood muscle disease caused by mutations in the dystrophin gene. It is an X-linked, recessive disease and the most current data indicates it affects ~1:5,000 newborn males.1 It causes fatal muscle wasting ultimately leading to death by cardiac and respiratory complications by 20–30 years of age. Currently, treatment is limited to the use of corticosteroids2 but there is no cure. Numerous treatment strategies are under investigation. Pharmacologic approaches have mainly been targeted at the secondary features of dystrophin deficiency and subsequent muscle degeneration which includes inflammation, fibrosis, and fat replacement.3 Molecular-based strategies, including gene therapy, exon skipping, and mutation suppression are primarily targeted at replacing/restoring the mutated DMD gene.4 The initial challenge facing adeno-associated virus (AAV) as a delivery vehicle for dystrophin was the large size of the gene. This hurdle was partially overcome with the development of mini and micro-dystrophins,5,6 however, new challenges have emerged. The first clinical gene therapy trial with intramuscular delivery of AAV.mini-dystrophin revealed immune responses7 to dystrophin which could impact replacement strategies. Patients with genomic deletions in a region expressed by the mini-dystrophin transgene elicited a T-cell–mediated immune response. In addition, clusters of revertant fibers expressing dystrophin generated from a second site mutation, previously thought to be immunoprotective, were shown to prime an immune response following gene transfer in some patients.7 In the current approach, we are using AAV-mediated overexpression of ITGA7 as a surrogate for dystrophin replacement. ITGA7 is expressed endogenously in DMD and expectantly circumvents immune issues.

The dystrophin–glycoprotein complex links the internal cytoskeletal actin and the extracellular matrix (ECM) and stabilizes the sarcolemma during muscle activity. Without it, the membrane loses stability allowing an influx of calcium ions and ultimately leads to muscle fiber death followed by replacement with fat and fibrosis.8 α7 Integrin is a laminin receptor in skeletal and cardiac muscle that also links the ECM on the surface of muscle cells with the intracellular actin cytoskeleton. α7 is present throughout the sarcolemma and is enriched at the myotendinous and neuromuscular junction. The protein forms a heterodimer with β1 integrin, and the β1 subunit participates in linkage to the actin cytoskeleton through various proteins such as talin, vinculin, α-actinin, and integrin-linked kinase (ILK).9 A putative downstream target of α7 is ILK. An ILK knockout mouse model has a very similar muscle phenotype to α7-deficient mice. When ILK is deleted, there is a detachment of actin from the membrane, suggesting a role for ILK as a linker from the actin cytoskeleton to the ECM.10 This interaction is also shown to be involved in activation of the AKT/mTOR pathway that promotes muscle hypertrophy and resistance to apoptosis, demonstrating that α7 integrin plays not only a structural role but also a signaling role.11

α7 has been shown to be an important modifier of dystrophic symptoms. The studies of Burkin et al. showed that transgenic expression of the rat isoform of α7 in dystrophin/utrophin double knockout mice (mdx/utrn−/−) promoted satellite cell proliferation and activation, maintenance of muscle integrity, fostered muscle hypertrophy and reduced cardiomyopathy.12 Knockout of both dystrophin and α7 integrin produced a significantly more severe dystrophic phenotype further supporting a compensatory role for α7 integrin for dystrophin.13 In addition, mutations in ITGA7 cause congenital myopathy in both patients and mice.14,15,16

As a proof of principle for translation of AAV8.ITGA7 gene therapy, we investigated whether upregulation of α7 integrin following AAV delivery could be used as a potential therapy for DMD. We found that increased α7 expression significantly protected against loss of force following eccentric contraction-induced injury compared with untreated (contralateral) muscles but did not increase specific force following tetanic contraction. Gene therapy also reversed muscle pathology, increased muscle fiber diameter, and stabilized sarcolemmal integrity as evidenced by a reduction in Evans blue dye (EBD) uptake. Our results show that enhanced α7 overexpression provides a potential therapeutic approach for DMD.

Results

To investigate α7 overexpression in muscle, we generated an AAV expression cassette consisting of the human α7 cDNA (ITGA7) driven by a muscle-specific MCK promoter and packaged it using an AAV8-like capsid (rh.74, hereafter referred to as AAV8).17,18 We tested the potency of the vector (rAAV8.MCK.ITGA7) using intramuscular injection of 1 × 1011 vector genomes (vg) into the tibialis anterior (TA) muscle of 4-week-old mdx mice (n = 5). Four weeks post-injection, human α7 expression was quantified by immunofluorescence using a polyclonal antibody specific for the human protein. Fiber counts revealed that in rAAV8.MCK.ITGA7-treated TA muscle, 64 ± 5.02% of muscle fibers had sarcolemmal expression of human α7 (data not shown). There was no cross-reactivity with mouse α7.

Isolated limb perfusion of ITGA7 by AAV8 in the mdx mouse

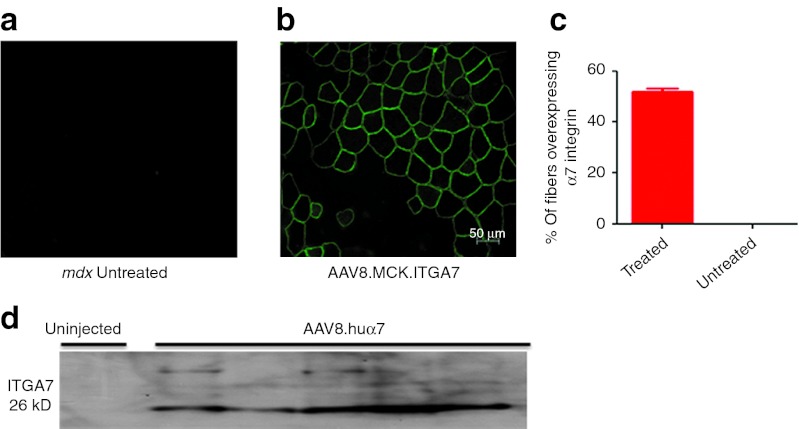

Isolated limb perfusion (ILP) via the femoral artery is a clinically relevant model for delivery of rAAV8.MCK.ITGA7. This approach enables widespread gene delivery to lower limb muscles following catheterization of the femoral artery.19 We perfused 1 × 1012 vg rAAV8.MCK.ITGA7 to the hind limb of 4-week-old mdx mice (n = 9). The TA, extensor digitorum longus (EDL), and the gastrocnemius were harvested 6 weeks after perfusion. Human α7 expression was quantified by immunofluorescence using a polyclonal antibody against the human protein (Figure 1a,b). Fiber counts (n = 7) revealed that 50 ± 4% of treated muscle fibers showed sarcolemmal expression of human α7 (Figure 1c). Consistent with the immunofluorescence data, western blot analysis on a subset of the samples (n = 5) revealed the presence of human α7 in the rAAV8.MCK.ITGA7-treated muscles (Figure 1d).

Figure 1.

Expression of human α7 in the mdx mouse hind limb following isolated limb perfusion of rAAV8.MCK.ITGA7. (a) Untreated muscle fibers show no α7 integrin staining in contralateral limb muscle. (b) Immunostaining with an antibody specific to ITGA7 reveals α7 integrin in rAAV8.MCK.ITGA7-treated mdx muscles; ITGA7 antibody only recognizes human ITGA7 and does not cross-react with mouse α7. (c) Quantification of the average percentage of myofibers overexpressing α7 integrin in rAAV8.MCK.ITGA7-treated mdx muscles (n = 7; error bar, SEM). (d) Western blot analysis for α7 integrin demonstrates the presence of a 26 kD cleavage fragment in mdx-treated muscle (n = 5) which is absent in control mdx samples (n = 2). AAV, adeno-associated virus.

rAAV8.MCK.ITGA7 treatment improves dystrophic pathology in mdx mice

In mdx mice, dystrophic changes first manifest as widespread muscle regeneration marked by centralized nuclei, as previously reported.20 Our experimental paradigm tested whether treatment in young mdx mice (4 weeks) prevented dystrophic pathology. Following vascular delivery of rAAV8.MCK.ITGA7, animals harvested 6 weeks after gene transfer showed a reduced number of central nuclei (treated: 73.2 ± 2.2 versus mdx: 80.1 ± 1.0; **P < 0.01; Figure 2a). Based on prior studies that showed that α7 integrin promoted myofiber hypertrophy,12 we analyzed the average fiber diameter in rAAV8.MCK.ITGA7-treated mdx muscles versus control. In rAAV8.MCK.ITGA7-treated mdx muscle (n = 7), the mean fiber diameter of all muscle fibers was slightly larger but not significantly increased comparing to the untreated side (untreated: 36.03 ± 1.62 versus treated: 37.10 ± 1.33) (Figure 2b). Qualitatively, we appreciated a difference in the diameter of fibers transduced with ITGA7 versus untransduced fibers. To specifically address whether AAV8.ITGA7 gene transfer increases fiber size, we next compared the diameters of transduced fibers versus untransduced fibers from both the treated and contralateral muscle. To make the most direct comparison, we only included fast twitch glycolytic (type IIb) fibers in the analysis which is the predominant fiber type in the TA.21 We found that α7-transduced fibers were significantly larger than both the untransduced fibers in the same muscle and those of the untreated contralateral side (transduced: 47.98 ± 1.06 versus untransduced: 42.85 ± 1.79 versus control: 43.35 ± 1.39; *P < 0.05) (Figure 3a,b). Taken together, these data show that α7 leads to a reduction in centralized nuclei and promotes myofiber hypertrophy.

Figure 2.

rAAV8.MCK.ITGA7 treatment improves histology in mdx mice. (a) rAAV8.MCK.ITGA7 treatment in mdx mice results in a decrease in centralized nuclei, a hallmark of DMD pathology, compared with untreated mdx controls (**P < 0.01). (b) Quantification of the average fiber diameter of rAAV8.MCK.ITGA7 treated (includes transduced and untransduced fibers) versus untreated (contralateral side) mdx muscle shows no difference in fiber diameter following hematoxylin and eosin staining. Error bars, SEM for (n = 7). (c) Hematoxylin and eosin images of treated rAAV8.MCK.ITGA7 mdx muscle (right) illustrate a decrease in the number of centralized nuclei compared with untreated contralateral mdx muscle. AAV, adeno-associated virus; DMD, Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

Figure 3.

rAAV8.MCK.ITGA7 treatment promotes myofiber hypertrophy. (a) Co-immunofluorescence staining shows myosin-stained (red cytoplasm) type IIb (red) fibers counterstained with α7 (green membrane) in a treated TA muscle illustrating larger fiber size diameter. (b) In this histogram, the fiber size diameter of the transduced type IIb fibers (red) can be directly compared with untransduced type IIb fibers (green) in the same treated muscle and in control muscle (black) from contralateral side (transduced (red) = 47.98 ± 1.06 versus untransduced (green) = 42.85 ± 1.79 versus control (black) = 43.35 ± 1.39; *P < 0.05). Error bars represent SEM for n = 4. AAV, adeno-associated virus; TA, tibialis anterior.

α7 Stabilizes and improves muscle membrane integrity in mdx mice

Next, we examined whether treatment of rAAV8.MCK.ITGA7 improved muscle membrane integrity. Mice were injected with rAAV8.MCK.ITGA7 and 6 weeks post-injection were subjected to a downhill running protocol and injected with EBD. Mice were euthanized 24 hours after EBD. The mdx mice (n = 6) treated with rAAV8.MCK.ITGA7 (Figure 4a) had 55% fewer positive EBD fibers compared with untreated contralateral muscle (treated: 5.98 ± 1.92 EBD versus untreated: 13.59 ± 1.52 EBD; **P < 0.01) (Figure 4b). EBD fibers were quantified as a percent out of a total of 1,500 fibers counted per animal. More importantly, no fibers that were expressing rAAV8.MCK.ITGA7 were positive for EBD, demonstrating that overexpression of α7 offered robust protection of myofiber membranes related to exercise-induced damage (Figure 4c).

Figure 4.

rAAV8.MCK.ITGA7 treatment improves muscle membrane integrity. Mdx muscles treated with 1 × 1011 vg of rAAV8.MCK.ITGA7 were compared with untreated contralateral mdx muscles for Evans blue dye uptake at 6 weeks post gene transfer following downhill running. (a) ITGA7-treated mdx muscle and (b) untreated contralateral muscle stained with an antibody specific to α7 integrin (green) and Evans blue dye (orange). (c) Quantification of the percentage of Evans blue positive fibers in treated versus untreated mdx muscle. rAAV8.MCK.ITGA7 treatment significantly protected mdx muscle membranes against Evans blue dye uptake compared with untreated (contralateral) muscles (**P < 0.01). Evans blue dye fibers were quantified as a percent out of a total of 1,500 fibers counted per animal. Error bars, SEM for (n = 6). AAV, adeno-associated virus; EBD, Evans blue dye; vg, vector genome.

Additional α7 integrin protects mdx muscle from contraction-induced damage

To test whether increasing expression of α7 could protect mdx muscle from contraction-induced injury and increase overall force, we looked at the functional properties of the EDL muscle from mdx mice treated with rAAV8.MCK.ITGA7. Using ILP, we tested two doses: low (3 × 1011 vg) and high (1 × 1012 vg), and compared muscle from the treated limb with the contralateral untreated in mdx and wild-type C57BL/10 control muscles. Six weeks post-injection, animals were euthanized and the EDL was removed for in vitro force measurements. rAAV8.MCK.ITGA7-treated muscles showed no significant improvement in normalized specific force when compared with the untreated (contralateral) muscle with both doses (Figure 5a). After assessment of total and specific force, the muscles were subjected to mechanical damage by repetitive eccentric contractions. α7 Overexpression significantly protected against contraction-induced injury. Analyzing the force generation after each contraction by comparing the ratio of each contraction versus the first contraction revealed that after the tenth contraction, mdx-untreated muscle decayed to 0.30 ± 0.03 versus high-dose–treated 0.48 ± 0.05. The muscles receiving high dose α7 were significantly more resistant compared with untreated mdx (*P < 0.05 or **P < 0.01) after contractions 3 until 10; the high-dose–treated group showed the same degree of protection as wild-type controls, which decayed to 0.42 ± 0.01 (Figure 5b). This data shows that increasing expression of α7 integrin leads to significant protection from contraction-induced injury, although it does not improve overall force of the muscle following tetanic contraction.

Figure 5.

Additional α7 integrin protects mdx muscle from contraction-induced damage. Mdx muscles treated by isolated limb perfusion via the femoral artery with 1 × 1012 vg (high dose, red) and 3 × 1011 vg (low dose, green) of rAAV8.MCK.ITGA7 (mouse) were compared with untreated contralateral mdx EDL muscles (blue) and WT (C57BL/10) EDL muscles (black) 6 weeks post gene transfer. (a) Measurement of normalized specific force following tetanic contraction in rAAV8.MCK.ITGA7-treated muscles was not increased with either low or high dose compared with untreated contralateral mdx muscle. (b) Muscles were then assessed for loss of force following repetitive eccentric contractions. Both dose cohorts of rAAV8.MCK.ITGA7 (green and red) significantly protected mdx muscle from loss of force compared with untreated (contralateral) muscles (blue). Two-way analysis of variance demonstrates significance in decay curves (***P < 0.001). Moreover, Bonferroni post-hoc analysis revealed that in the high dose (red) force retention following contractions 3–10 (*P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01) showed no significant difference from WT muscles (black). Error bars, SEM for n = 9 (rAAV8.MCK.ITGA7), 5 (WT, C57BL/10), or 19 (mdx) muscles per condition. AAV, adeno-associated virus; EDL, extensor digitorum longus; vg, vector genome; WT, wild-type.

Discussion

Despite the enormous effort devoted to finding a treatment for DMD, there is still no cure or effective therapy beyond the modest effect of steroids.2 Gene replacement strategies using AAV to deliver mini- and micro-dystrophin continue to hold promise although immunogenicity may be a potential barrier to success.7 Clearly, rAAV8.MCK.ITGA7 gene therapy has the potential advantage of gene expression with efficacy for DMD patients without eliciting an immune response. DMD patients endogenously express α7 which is modestly increased due to their disease state22 and will therefore not prime an immune response to the transgene.

The potential mechanism for improvement following upregulation of α7 remains unclear. Data from α7 transgenic mdx/utrn−/− mice has shown that α7 signaling leads to the activation of AKT/ mTOR through ILK promoting growth and reducing apoptosis.11,23 This finding is supported by our data in mdx muscle fibers transduced with rAAV8.MCK.ITGA7 given that we observed increase in muscle fiber size following gene delivery. Recent data has also indicated a potential link between α7 and sarcospan. The sarcospan/α7 double knockout mouse exhibited a more severe phenotype than either knockout alone. This more closely simulates the severity of the clinical DMD phenotype.24 The sarcospan null mice demonstrate a decrease in dystrophin glycoprotein complex components while conversely α7 expression is increased, favoring compensatory role for this novel peptide. Thus, one possible conclusion is that sarcospan modulates integrin signaling and is essential for ECM attachment and force development in muscle.

Muscles of DMD patients and mdx mice are susceptible to exercise-induced damage.25,26 Our results also show that α7 integrin is playing a structural role by protecting the muscle from contraction-induced injury and prevents EBD uptake even in the absence of dystrophin. However, the dichotomy between contraction-induced injury and force generation was striking in our therapy targeted toward induction and upregulation of α7. We cannot be sure of the translational benefit of membrane protection in the absence of force generation. We can speculate, however, that preventing muscle breakdown by reducing membrane fragility has the potential to protect against muscle fiber loss. Recent studies support this hypothesis showing that α7 RNA and total protein increases following eccentric exercise protecting injured muscles by facilitating muscle repair and structural integrity.27 Thus, α7 therapy may help prevent repetitive cycles of injury and help to preserve muscle function overtime. This has the potential to change the natural history of DMD. It may also be that α7 gene therapy is best suited to be a combinational therapy with products such as follistatin that have the contrasting benefit of enhancing force generation while not specifically protecting against contraction-induced injury.26

The findings from this study may also be applicable to other muscular dystrophies, such as α7 integrin congenital myopathy and merosin-deficient congenital muscular dystrophy 1A (MDC1A), where it has been shown that transgenic overexpression of α7 reduced muscle pathology and increased longevity of the dyw mouse model for MDC1A.28

Materials and Methods

All procedures were approved by The Research Institute at Nationwide Children's Hospital Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Three to four weeks old mdx mice and normal age-matched C57BL/10 controls were used for all studies.

α7 Integrin gene construction. The full-length human α7 cDNA (GenBank accession no. AF072132) was codon optimized and synthesized by GenScript, Piscataway, NJ. The cDNA was cloned into an AAV2 inverted terminal repeat containing plasmid which contained a consensus Kozak sequence, an SV40 intron, and a synthetic polyadenylation site. An MCK promoter/enhancer (GenBank accession no. M21390)-derived sequence was used to drive muscle-specific gene expression. The promoter was synthesized by GenScript following derivation from previous work29,30 with some modifications. It is composed of the mouse MCK enhancer (206 bp) fused to the 351 bp MCK promoter (-351-0 MCK). After the promoter, the 53 bp endogenous mouse MCK Exon 1 (untranslated) was added for efficient transcription initiation (Supplementary Figure S1). This inclusion has been shown to improve expression with other promoters including CMV and troponin.31,32 Salva and colleagues have also shown that the addition of 50 bp from MCK exon 1 improves expression.33 The MCK exon 1 was followed by the SV40 late 16S/19S splice signals (97 bp) and a small 5′-UTR (61 bp). The intron and 5′-UTR are derived from plasmid pCMVβ (Clontech, Mountain View, CA).19

rAAV production. rAAV vectors were produced by a modified cross-packaging approach whereby the AAV type 2 inverted terminal repeats can be packaged into multiple AAV capsid serotypes.34 Production was accomplished using a standard 3-plasmid DNA CaPO4 precipitation method using HEK293 cells. 293 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% cosmic calf serum and penicillin and streptomycin. The production plasmids were: (i) pAAV.MCK.ITGA7, (ii) rep2-cap8–modified AAV helper plasmids encoding cap serotype 8-like isolate rh.74, and (iii) an adenovirus type 5 helper plasmid (pAdhelper) expressing adenovirus E2A, E4 ORF6, and VA I/II RNA genes. Vectors were purified from clarified 293 cell lysates by sequential iodixanol gradient purification and anion-exchange column chromatography using a linear NaCl salt gradient as previously described.35 A quantitative PCR-based titration method was used to determine an encapsidated vg titer utilizing a Prism 7500 Taqman detector system (PE Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA).35 The primer and fluorescent probe targeted the MCK promoter and were as follows: MCK forward primer, 5′-CCCGAGATGCCTGGTTATAATT-3′ MCK reverse primer, 5′-GCTCAGGCACAGGTGTTG-3′ and MCK probe, 5′-FAM-CCAGACATGTGGCTGCTCCCCC-TAMRA-3′.

AAV vector delivery through ILP to mouse muscle. Four weeks old mdx mice were treated with 3 × 1011 and 1 × 1012 vg of rAAV8.MCK.ITGA7 by injection into the femoral artery as previously described.19 Mice were sedated with a ketamine/xylazine cocktail (100 and 10 mg/kg), the left groin shaved and prepped with a 95% EtOH and providine solution, and the animal was secured onto a warm dissecting scope. The femoral bundle was exposed with a single scalpel (no. 11 Blade) incision (0.25 cm) and blunt dissected to expose the femoral artery and vein. A 3-0 braided silk tourniquet was placed loosely around the vessels above the site of incision and tightened at the appropriate time to isolate the artery from the general circulation. The femoral artery was catheterized with a custom heat-pulled polypropylene (PE 10) catheter following placement of a site of entry using a 33-gauge needle. The arterial catheter was flushed with sterile saline, 100 µl. The tourniquet was applied, and the volume of virus (100 µl) was administered with slow pressure over 1 minute. With the virus injected and the tourniquet secured, a dwell time of 10 minutes was allowed. Sterile saline (100 µl) was administered as a post flush. The catheter and the tourniquet were then removed and direct pressure applied to control the bleeding. The wound was flushed with saline and closed with a single 5-0 restorable suture. Mice were allowed to recover on a 37° warmer and once ambulatory, returned to their cage. In addition, animals received a postoperative dose of buprenorphine (0.1 mg/kg). Animals were analyzed 6 weeks after gene transfer.

Force generation and protection from eccentric contractions. Mice were euthanized 6 weeks post-injection to allow for transgene expression. EDL muscles from both legs were dissected at the tendons and placed in Krebs-Henselet buffer. Muscles were subjected to physiological analysis using a protocol described by our lab19 with some adaptations. One tendon was tied to a force transducer and the other tendon was tied to a linear servomotor. Once the muscle was stabilized, the resting tension was set to a length (optimal length) where twitch contractions were maximal. After a rest period of 10 minutes without stimulation, a tetanic contraction was applied (500-ms tetanus at 150 Hz). Following 5 minutes of rest, an eccentric contraction protocol was used as previously described by Liu and colleagues5 with some modifications. The muscles were subjected to a series of 10 isometric 700-ms contractions, occurring at 2-minute intervals, with a 5% stretch-re-lengthening procedure executed between 500 and 700 ms (5% stretch over 100 ms, followed by return to optimal length in 100 ms). Following the tetanus and eccentric contraction protocol, the muscle was removed, wet-weighed, mounted on chuck using gum tragacanth, and then frozen in isopentane cooled in liquid nitrogen.

Immunofluorescence. Cryostat sections (12 µm) were incubated with a polyclonal human α7 primary antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) or a monoclonal myosin type IIb antibody (10F5) (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Iowa City, IA) both at a dilution of 1:100 in a block buffer (1× phosphate-buffered saline, 10% goat serum, 0.1% Triton X-100) for 1 hour at room temperature in a wet chamber. Sections were then washed with phosphate-buffered saline three times, each for 10 minutes and re-blocked for 30 minutes. AlexaFluor488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody or AlexaFluor 568-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgM secondary antibody were applied at a 1:250 dilution for 45 minutes. Sections were washed in phosphate-buffered saline three times for 10 minutes and mounted with Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA).

Western blot analysis. Tissue sections from the left treated TA muscle and the right contralateral TA muscle (20-20 µ thick) were collected into a microcentrifuge and homogenized with 100 µl homogenization buffer (125 mmol/l Tris-HCl, 4% SDS, 4 mol/l urea) in the presence of one protease inhibitor cocktail tablet (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). After homogenization, the samples were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 minutes in the cold. Protein was quantified on NanoDrop (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). Protein samples (25 µg) were electrophoresed on a 3–8% polyacrylamide Tris-acetate gel (NuPage; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 1 hour at 150 V and then transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) for 1 hour at 35 V. The membrane was blocked in 5% nonfat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 for 1 hour, and then incubated in a 1:500 dilution of a polyclonal human α7 antibody (Abcam) and 1:6,000 of a γ-tubulin monoclonal antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO). Anti-mouse and anti-rabbit secondary antibody-HRP (Millipore, Billerica, MA) was used for ECL immunodetection.

Histology and cross-sectional area. Muscle cross-sectional fiber diameters and percentage of myofibers with centrally located nuclei were determined from TA muscles stained with hematoxylin and eosin from 10-week-old mice injected with rAAV8.MCK.ITGA7 and the control uninjected TA (n = 5 TA muscles per group; three random ×20 images per section per animal) were taken with a Zeiss AxioCam MRC5 camera (Carl Zeiss Microscopy, Thornwood, NY). Fiber diameter was measured using Zeiss Axiovision LE4 software (Carl Zeiss Microscopy).

EBD assay. At 4 weeks of age, mdx mice were injected with 1 × 1011 vg of rAAV8.MCK.ITGA7 to the left gastrocnemius and TA muscle. Six weeks post-treatment mice were run on a treadmill (Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH) at −12° downhill decline at 15 m/minute for 25–30 mins. The speed was gradually increased from 10 to 15 m/minute during a 2-minute warm-up period. Mice were then injected intraperitoneally on the right side at 5 µl/g body weight with a filter sterilized 10 mg/ml EBD in 1× phosphate buffer solution. Mice were then euthanized 24 hours post-injection and tissues were harvested and sectioned. Sections were fixed in cold acetone for 10 minutes and then the immunofluorescence protocol was used to stain for human α7. EBD fibers were quantified as a percent out of a total of 1,500 fibers counted per animal.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Figure S1. MCK enhancer/promoter sequence.

Acknowledgments

We thank the NCH Viral Vector Manufacturing Facility for supplying vector for this study. The myosin type IIb antibody (10F5) developed by Christine Lucas was obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank developed under the auspices of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and maintained by The University of Iowa, Department of Biology, Iowa City, IA 52242. This work has been funded by the Senator Paul D. Wellstone Muscular Dystrophy Cooperative Research Center grant (1U54HD066409) at Nationwide Children's Hospital, and a Paul D. Wellstone Muscular Dystrophy Cooperative Research Center Graduate Student Training Fellowship (to K.N.H). The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

MCK enhancer/promoter sequence.

REFERENCES

- Mendell JR, Shilling C, Leslie ND, Flanigan KM, al-Dahhak R, Gastier-Foster J.et al. (2012Evidence-based path to newborn screening for Duchenne muscular dystrophy Ann Neurol 71304–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendell JR, Moxley RT, Griggs RC, Brooke MH, Fenichel GM, Miller JP.et al. (1989Randomized, double-blind six-month trial of prednisone in Duchenne's muscular dystrophy N Engl J Med 3201592–1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik V, Rodino-Klapac LR., and, Mendell JR. Emerging drugs for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2012;17:261–277. doi: 10.1517/14728214.2012.691965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendell JR, Rodino-Klapac L, Sahenk Z, Malik V, Kaspar BK, Walker CM.et al. (2012Gene therapy for muscular dystrophy: lessons learned and path forward Neurosci Lett 52790–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M, Yue Y, Harper SQ, Grange RW, Chamberlain JS., and, Duan D. Adeno-associated virus-mediated microdystrophin expression protects young mdx muscle from contraction-induced injury. Mol Ther. 2005;11:245–256. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Li J., and, Xiao X. Adeno-associated virus vector carrying human minidystrophin genes effectively ameliorates muscular dystrophy in mdx mouse model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:13714–13719. doi: 10.1073/pnas.240335297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendell JR, Campbell K, Rodino-Klapac L, Sahenk Z, Shilling C, Lewis S.et al. (2010Dystrophin immunity in Duchenne's muscular dystrophy N Engl J Med 3631429–1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien KF., and, Kunkel LM. Dystrophin and muscular dystrophy: past, present, and future. Mol Genet Metab. 2001;74:75–88. doi: 10.1006/mgme.2001.3220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brakebusch C., and, Fässler R. The integrin-actin connection, an eternal love affair. EMBO J. 2003;22:2324–2333. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gheyara AL, Vallejo-Illarramendi A, Zang K, Mei L, St-Arnaud R, Dedhar S.et al. (2007Deletion of integrin-linked kinase from skeletal muscles of mice resembles muscular dystrophy due to alpha 7 beta 1-integrin deficiency Am J Pathol 1711966–1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boppart MD, Burkin DJ., and, Kaufman SJ. Activation of AKT signaling promotes cell growth and survival in a7ß1 integrin-mediated alleviation of muscular dystrophy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1812:439–446. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkin DJ, Wallace GQ, Milner DJ, Chaney EJ, Mulligan JA., and, Kaufman SJ. Transgenic expression of {alpha}7{beta}1 integrin maintains muscle integrity, increases regenerative capacity, promotes hypertrophy, and reduces cardiomyopathy in dystrophic mice. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:253–263. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)62249-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rooney JE, Welser JV, Dechert MA, Flintoff-Dye NL, Kaufman SJ., and, Burkin DJ. Severe muscular dystrophy in mice that lack dystrophin and alpha7 integrin. J Cell Sci. 2006;119 Pt 11:2185–2195. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo C, Willem M, Werner A, Raivich G, Emerson M, Neyses L.et al. (2006Absence of alpha 7 integrin in dystrophin-deficient mice causes a myopathy similar to Duchenne muscular dystrophy Hum Mol Genet 15989–998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer U, Saher G, Fässler R, Bornemann A, Echtermeyer F, von der Mark H.et al. (1997Absence of integrin alpha 7 causes a novel form of muscular dystrophy Nat Genet 17318–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi YK, Chou FL, Engvall E, Ogawa M, Matsuda C, Hirabayashi S.et al. (1998Mutations in the integrin alpha7 gene cause congenital myopathy Nat Genet 1994–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin PT, Xu R, Rodino-Klapac LR, Oglesbay E, Camboni M, Montgomery CL.et al. (2009Overexpression of Galgt2 in skeletal muscle prevents injury resulting from eccentric contractions in both mdx and wild-type mice Am J Physiol, Cell Physiol 296C476–C488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodino-Klapac LR, Montgomery CL, Bremer WG, Shontz KM, Malik V, Davis N.et al. (2010Persistent expression of FLAG-tagged micro dystrophin in nonhuman primates following intramuscular and vascular delivery Mol Ther 18109–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodino-Klapac LR, Janssen PM, Montgomery CL, Coley BD, Chicoine LG, Clark KR.et al. (2007A translational approach for limb vascular delivery of the micro-dystrophin gene without high volume or high pressure for treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy J Transl Med 545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres LF., and, Duchen LW. The mutant mdx: inherited myopathy in the mouse. Morphological studies of nerves, muscles and end-plates. Brain. 1987;110 Pt 2:269–299. doi: 10.1093/brain/110.2.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augusto V, Padovani CR., and, Campos GER. Skeletal muscle fiber types in C57BL6J mice. Braz J Morphol Sci. 2004;21:89–94. [Google Scholar]

- Hodges BL, Hayashi YK, Nonaka I, Wang W, Arahata K., and, Kaufman SJ. Altered expression of the alpha7beta1 integrin in human and murine muscular dystrophies. J Cell Sci. 1997;110 Pt 22:2873–2881. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.22.2873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lueders TN, Zou K, Huntsman HD, Meador B, Mahmassani Z, Abel M.et al. (2011The alpha7beta1-integrin accelerates fiber hypertrophy and myogenesis following a single bout of eccentric exercise Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 301C938–C946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall JL, Chou E, Oh J, Kwok A, Burkin DJ., and, Crosbie-Watson RH. Dystrophin and utrophin expression require sarcospan: loss of a7 integrin exacerbates a newly discovered muscle phenotype in sarcospan-null mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:4378–4393. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrof BJ. The molecular basis of activity-induced muscle injury in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Mol Cell Biochem. 1998;179:111–123. doi: 10.1023/a:1006812004945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellorusso C, Crawford RW, Chamberlain JS., and, Brooks SV. Tibialis anterior muscles in mdx mice are highly susceptible to contraction-induced injury. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2001;22:467–475. doi: 10.1023/a:1014587918367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boppart MD, Burkin DJ., and, Kaufman SJ. Alpha7beta1-integrin regulates mechanotransduction and prevents skeletal muscle injury. Am J Physiol, Cell Physiol. 2006;290:C1660–C1665. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00317.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doe JA, Wuebbles RD, Allred ET, Rooney JE, Elorza M., and, Burkin DJ. Transgenic overexpression of the a7 integrin reduces muscle pathology and improves viability in the dy(W) mouse model of merosin-deficient congenital muscular dystrophy type 1A. J Cell Sci. 2011;124 Pt 13:2287–2297. doi: 10.1242/jcs.083311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shield MA, Haugen HS, Clegg CH., and, Hauschka SD. E-box sites and a proximal regulatory region of the muscle creatine kinase gene differentially regulate expression in diverse skeletal muscles and cardiac muscle of transgenic mice. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:5058–5068. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.9.5058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuasa K, Sakamoto M, Miyagoe-Suzuki Y, Tanouchi A, Yamamoto H, Li J.et al. (2002Adeno-associated virus vector-mediated gene transfer into dystrophin-deficient skeletal muscles evokes enhanced immune response against the transgene product Gene Ther 91576–1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikovits W, Jr, Mar JH., and, Ordahl CP. Muscle-specific activity of the skeletal troponin I promoter requires interaction between upstream regulatory sequences and elements contained within the first transcribed exon. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:3468–3482. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.7.3468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simari RD, Yang ZY, Ling X, Stephan D, Perkins ND, Nabel GJ.et al. (1998Requirements for enhanced transgene expression by untranslated sequences from the human cytomegalovirus immediate-early gene Mol Med 4700–706. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salva MZ, Himeda CL, Tai PW, Nishiuchi E, Gregorevic P, Allen JM.et al. (2007Design of tissue-specific regulatory cassettes for high-level rAAV-mediated expression in skeletal and cardiac muscle Mol Ther 15320–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitz JE, Rolling F, Li C, Conrath H, Xiao W, Xiao X.et al. (2002Cross-packaging of a single adeno-associated virus (AAV) type 2 vector genome into multiple AAV serotypes enables transduction with broad specificity J Virol 76791–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark KR, Liu X, McGrath JP., and, Johnson PR. Highly purified recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors are biologically active and free of detectable helper and wild-type viruses. Hum Gene Ther. 1999;10:1031–1039. doi: 10.1089/10430349950018427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

MCK enhancer/promoter sequence.