Abstract

Post graduate learning and assessment is an important responsibility of an academic oral and maxillofacial surgeon. The current method of assessment for post graduate training include formative evaluation in the form of seminars, case presentations, log books and infrequently conducted end of year theory exams. End of the course theory and practical examination is a summative evaluation which awards the degree to the student based on grades obtained. Oral and maxillofacial surgery is mainly a skill based specialty and deliberate practice enhances skill. But the traditional system of assessment of post graduates emphasizes their performance on the summative exam which fails to evaluate the integral picture of the student throughout the course. Emphasis on competency and holistic growth of the post graduate student during training in recent years has lead to research and evaluation of assessment methods to quantify students’ progress during training. Portfolio method of assessment has been proposed as a potentially functional method for post graduate evaluation. It is defined as a collection of papers and other forms of evidence that learning has taken place. It allows the collation and integration of evidence on competence and performance from different sources to gain a comprehensive picture of everyday practice. The benefits of portfolio assessment in health professions education are twofold: it’s potential to assess performance and its potential to assess outcomes, such as attitudes and professionalism that are difficult to assess using traditional instruments. This paper is an endeavor for the development of portfolio method of assessment for post graduate student in oral and maxillofacial surgery.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12663-012-0381-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Oral and maxillofacial surgery, Post graduate, Assessment, Portfolio

Introduction

Oral and maxillofacial surgery is a unique specialty in dentistry, a bridge between dental and medical professions requiring extensive surgical training. Proliferation of knowledge in both medical and dental fields and the need for the post graduate to be competent in this complex field has resulted in extreme pressure on the educational process. Assessment drives learning [1] and hence assessment methods need to have enough rigors to assess post graduates’ competency in not only surgical skills, but also other non clinical skills like professionalism, critical thinking and reflective learning. The current assessment method for post graduate program as prescribed by Dental Council of India [2] and which is followed at our institute in oral and maxillofacial surgery is of summative type i.e. end of the course written exam, practical or clinical exam and viva voce or oral examination. Though the curriculum for the course is elaborated extensively in terms of knowledge, skills and attitudes, it lacks to define specific learning outcomes and has poor assessment methods. The course duration is of 3 years and includes clinical rotations (annexure I).

This kind of wide-ranging training in a specialty requires learning outcomes clearly defined in each rotation along with specification of certain competencies, which are common across all domains of training. But the present method of assessment may not take into account any formative assessments that occur during training in the form of clinical bedside discussions, seminars, case presentations, end of year theory exams and log books. The primary purpose of formative assessment is to provide useful feedback on student strengths and weaknesses with respect to learning objectives. Formative testing takes place during the course of study so that student learners have the opportunity to understand what content they have already mastered and what needs more effort. Lack of assessment in various rotations leads to inadequate training, poorly met learning outcomes deficient in critical thinking and reflective learning. Too much reliability on summative written tests and clinical examination may not adequately assess the student.

Validity is indispensable to all kinds of assessments and it is the single most important characteristic of assessment data. It refers to the evidence presented to support or to refute the meaning assigned to results [3]. Basically, it is said that validity has to do with a test measuring what it is supposed to measure. There are five major sources of evidence to validity like content, response process, internal structure, relations to other variables and consequences. Any factors that interfere with the meaningful interpretation of assessment data are threat to validity. Messick [4] noted two major sources of validity threats: Construct underrepresentation (CU) and construct irrelevant variance (CIV). CU refers to the undersampling or biased sampling of the content domain by assessment instrument. For example, too few items to test the knowledge or too few cases to test the surgical skill lead to inadequately assessing a student. CIV is a systematic error introduced into the assessment data by variables unrelated to the content being measured but are due to improper process of exam. For example, flawed checklists, rating scales, questions too easy or too difficult, improperly designed questions in terms of ambiguity and marks distribution and poorly trained raters and raters bias.

Problem Analysis

In present assessment system for post graduates students have to take final exam at the end of three years, which consist of four written tests of 100 marks each, a clinical exam and viva voce. In terms of validity, present assessment method has CU as a threat to validity in that all four written examinations are of 100 marks each, with two long essays of twenty marks and 7 short essays of five marks each. This is surely a case of CU as there are too few items to sample the domain adequately. There is also threat to validity in terms of CIV in written exams as the questions are not well structured and are vague in nature. Blue printing of the theory exams is done to a certain extent but systematic sampling of the domains is unclear. The exams are scored subjectively by four different evaluators but they do not follow a structured scoring format. In clinical examination, there is no uniformity of the cases which the student presents for assessment as the cases allotted for presentation belong to different topics like trauma, cancer, cleft lip and palate and infections which affect validity in terms of CU. Another aspect of performance assessment in present system is inherent threat to validity in that all our patients are real patients as we do not use standardized patients. Hence present system has poor content validity, is less reliable and inconsistent. Psychomotor skill assessment in our system includes a minor procedure to operate like surgical disimpaction of tooth under local anesthesia. This has low threat to validity as case selection is standardized for difficulty index and need for sectioning of the tooth during the procedure for all the examinees. The viva voce is not structured oral examination and consists of all four evaluators testing the student. Apart from knowledge and skill, there are no methods to assess attitudes of post graduates and other non clinical skills. In general there is threat to validity both in terms of CU and CIV as the assessment methods employed are inadequate to assess all the learning outcomes in post graduate oral and maxillofacial surgery program.

Literature Review

Literature is ripe with data on different methods of assessments appropriate for post graduate program in medicine and dentistry in general but lack documentation in oral and maxillofacial surgery post graduate programs and specifically in Indian context. Reforms in this area must have occurred long ago in countries pioneered in education and assessment; and failure of our system to update and adopt appropriate assessment methods may be the reasons for this scarcity.

Assessment drives teaching and learning. Learning and assessment ideally need to be in alignment with each other and it is very important to determine learning outcomes or the competencies and then choose appropriate assessment tools for an effective educational experience. Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has developed six competencies for surgical residency namely patient care (PC), medical knowledge (MK), practice based learning and improvement (PBLI), interpersonal and communication skills (ICS), professionalism (P) and system based practices (SBP) [5]. Clinical performance is defined as the combination and integration of different competencies such as knowledge, clinical skills, attitudes and professionalism [6] and ideal assessment format should take into account the integral picture of the student [7]. A wide range of assessment methods currently available include written exams, patient management problems, modified essay questions (MEQs) checklists, objective structured clinical exam (OSCE), student projects, constructed response questions (CRQs), rating scales, extended matching items, tutor reports, portfolios, short case assessment and long case assessment, Mini clinical examination (Mini-CEX), log book, trainer’s report, audit, simulated patient surgeries, video assessment, simulators, self assessment, peer assessment, standardized patients, 360° evaluation and multisource feedback [8–10]. Multiple assessment methods should be employed so that the results could be triangulated for reliability and validity. Assessment methods at residency level should not only assess competence at all levels of Miller’s pyramid [7] but also need to emphasize on self-reflection, self-directed learning and broader areas like professionalism. Hence it is very important to use array of tools both traditional and nontraditional to assess competencies in post graduation. The four essential characteristics of an assessment system that are needed in order to accomplish two vital objectives like achieving predetermined learning outcomes and identification of problems at an early stage like formative assessment are as follows[11].

The focus must be on performance in the workplace.

The assessment must provide evidence of performance.

Evidence must be triangulated whenever possible.

Complete records must be kept.

A Proposed Solution

The focus of learning is being shifted from imbibing knowledge and skills by merely by being exposed to the problems in the hospital to a more focused and potentially more meaningful educational experience [5]. ACGME in collaboration with American Board Medical Specialties (ABMS) has provided a toolbox of assessment methods for six surgical competencies [12]. It is essential to use a range of tools so that assessment can result in less threat to validity both in terms of CU and CIV. Hence a comprehensive assessment method will be a collection of tools, assessing all aspects of knowledge, skill and attitude. Portfolio has essential characteristics of ideal assessment method and is used to support reflective practice, deliver summative assessment, aid knowledge management processes that are seen as a key connection between learning at organizational and individual levels in post-graduate healthcare education [13]. There are different types of portfolios such as showcase portfolio, reflective portfolio, a process portfolio, an assessment portfolio and many others. Portfolios are relatively new to healthcare but the last decade has seen exponential growth in the use and application of portfolio method of assessment across all disciplines of medical education. Portfolio use is suggested not only for student and post graduate assessment but also for licensure exam, faculty tenure and promotions.

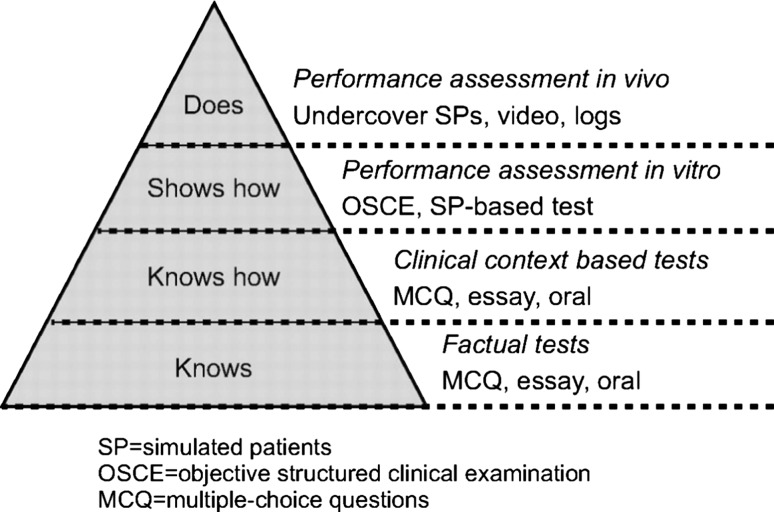

In general terms, a portfolio can be defined as a collection of evidence that learning has taken place [14]. However, the term is used to describe a plethora of learning tools that differ widely in content, usage and assessment requirements [15]. Portfolio can also be defined as a focused purposeful collection of student work that documents evidence of traditional and nontraditional sources of student learning, progress and achievement and include student participation in selection of portfolio content, guidelines for selection and criteria for judging merit and evidence of self reflection [16]. Research has suggested that the evaluation of competency is best attained through the use of authentic assessment [17] and Chambers opine that portfolios are one form of authentic assessment where actual examples of student work are displayed [18]. It allows the collation and integration of evidence on competence and performance from different sources to gain a comprehensive picture of everyday practice. Student faculty link is an important component in the portfolio process and can serve as a platform for discussion between students and faculty members to help theory–practice gap [19]. It is just not a logbook with learning experiences but evidence of annotated documentation of the learner’s reflections regarding his or her learning. The learners, depending on their reflective ability, may reflect on the learning experiences at three different cognitive levels: descriptive, analytical, and evaluative [20]. Miller [7] identifies four levels at which students need to be assessed: ‘‘knows’’—factual recall of knowledge; ‘‘knows how’’—application of knowledge; ‘‘shows how’’—an examination where competence is assessed and the student knows that they are being watched; and ‘‘does’’—assessment of performance in a real-life setting and need not be framed as an exam. Wass et al. (Fig. 1) have adapted Miller’s framework for clinical assessment in medicine to focus on validity throughout the pyramid by using various instruments appropriate for assessment at each level [21]. This focus on validity means selecting and using tests that actually succeed in measuring facets of clinical competence that they were designed to test. Appropriate assessment methods which assesses at each level of Miller’s pyramid like written tests, MCQs, short answers, structured viva, OSCE, simulation tests and clinical performance on real patients using checklists and global rating scale can be included in portfolio framework. Its multipurpose use for both formative as well as summative assessment makes it a flexible yet a robust method for holistic assessment [22]. It is found that portfolio can be a valid method when adequate sampling across all required competencies takes place and to make it reliable it is necessary to use competence based blue print, clear assessment criteria, guidelines and experienced raters in the development of portfolio as well as in assessment procedure [6, 23].

Fig. 1.

Wass et al.’s [22] adaptation of Miller’s framework for clinical assessment. Source reprinted with permission from Wass et al. [22]. Assessment of clinical competence

The process starts with the strategic planning phase of identifying and defining competencies based on a blueprint with four dimensions needed for portfolio development. They are as follows;

Content of the Portfolio

Post graduate program is of 3 years (PGY 1, 2, 3) duration. Each year has clinical rotations, exodontia and hospital based oral and maxillofacial surgery (OMFS) postings are repeated every year and are of longer duration (Supplementary Tables 1–3). The list of learning outcomes chosen for this portfolio method of assessment is not exhaustive and comprehensive listing of learning outcomes for this entire program is beyond the scope of this paper, specific activities have been selected leading to learning outcomes based on ACGME’s competencies for surgical post graduates for each clinical rotation and appropriate assessment tool which will be documented in portfolio.

Most of the learning activities are emphasized in exodontia and hospital based postings OMFS as they are related to competencies of patient care, medical knowledge and PBLI. Annexure 1 illustrates learning activity and outcome, competency domain, assessment tool and portfolio entry for each clinical rotation.

Each clinical rotation will have assessment method most suitable for that subject and portfolio entry can be the scores of MCQ, written tests, OSCE, Mini Clinical examination exercise (Mini—CEX), Chart stimulated recall and or oral examination (CSR), scores from checklists and global rating scales, self assessment and faculty assessment reports, work logs showing number of tasks or cases performed. Though 360° assessment and patient survey results are recommended as most desirable for certain competencies but incorporating them in our portfolio was not feasible because of its extensive nature. Portfolio will also include evidence of learner reflection; each entry in portfolio will have cover letter indicating self reflection about that particular topic or rotation, strengths acknowledged and weakness to be improved.

The assessment tools available at ACGME website for assessing six surgical competencies will be appropriately modified and adopted to suit our requirements.

Criteria for Judging Merit

We chose a global rating scale to evaluate a portfolio entry. Two post graduate teachers who are not mentoring the student to be assessed will be rating the portfolio on the basis of completion of prescribed learning exercises, scores of written tests, seminars, group discussions, OSCE checklists and global rating scores and holistic assessment on reflective writing. Each portfolio entry will be scored by the rater by considering the scores of the assessment tool used and scores of reflection record provided and then converting them into percentage.

Rater Guidelines/Training and Development of Rubric

In education jargon, the word rubric means “an assessment tool for communicating expectations of quality” or “a standard of performance for a defined population” [24]. A series of benchmarks or performance indicators describing the outcome expectancy of each learning experience will be outlined for raters training. The knowledge, skills, and attitudes underpinning each competency will be clearly defined and will be measurable using a rubric to avoid ambiguity while rating portfolios.

The rating for each portfolio entry will be scored in terms of percentage and then it will subsequently graded into four categories for each of the twenty rotations namely.

Good—80 % and above.

Satisfactory—65 % and above.

Borderline—50 % and above.

Not satisfactory—<50 %.

As we plan to use assessment tools available at ACGME, which are already validated we expect that our assessment system will have low threat to validity.

The post graduate students will be instructed in an orientation course along with raters on how to choose portfolio entries during each year, how to prepare for required competency, on methods of documentation and reflective learning. Inter rater reliability can be increased by providing explicit set of scoring guidelines. Each entry scored by different rater and using multiple raters can also increase inter rater reliability. Specific topic entry into portfolio can be made during that clinical rotation hence saving time and using that time effectively for reflection. The topics prescribed were based on each year of training and competency in exodontia and hospital based OMFS are repeated and further extended every year as they are core subjects of the specialty.

Conclusion

Post graduate program in oral and maxillofacial surgery will definitely benefit from this comprehensive method of assessment as it can evaluate the student from multiple sources across all domains of competencies and at all levels of Miller’s pyramid during various clinical rotations present in a structured training program. Portfolio as an assessment tool can be complemented to the existing method of assessment and for post graduates to take it seriously, portfolio can be made as a deciding factor for eligibility for final examination or portfolio should constitute for 30 % in final examination.

The issues of validity in terms of CU have been countered by choosing different and appropriate assessment tools to cover knowledge, skill and attitude across all domains ensuring the ACGME competencies and thus providing triangulation. CIV will be avoided by standardizing case presentations, self assessment and faculty assessment by standardized questionnaires for ethics and professionalism, by validating OSCEs, MCQs and questions for written tests or by using already validated tools. Portfolio assessment demands time and commitment from both faculty and students but the efforts can result in excellent student mentor relationship, provision for feedback to learners so that they can learn from their mistakes and build on achievements and inculcate self reflection and lifelong learning.

Electronic Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Crossley J, Humphris G, Jolly B. Assessing health professionals. Med Educ. 2002;36:800–804. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anonymous. Dental Council of India, Course regulations for Master of Dental Surgery. http://www.dciindia.org/dciregulation_2006_pages/MDS-Course_Regulation_2007.htm. Assessed 16 May 2011

- 3.Downing SM, Yudowsky R. Assessment in health professions education. New York: Routledge Group; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Messick S. Validity. In: Linn RL, editor. Educational measurement. 3. New York: American Council on Education and Macmillan; 1989. pp. 13–104. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mery CM, Greenberg JA, Patel A, Jaik NP (2008) Teaching and assessing the ACGME competencies in surgical residency. Bull Am Coll Surg 93(7)39–47. http://www.aats.org/multimedia/files/ACGME-Competencies-In-Srgical-Rresidencies-ACS.pdf. Accessed 23 May 2011 [PubMed]

- 6.Michels NRM, Driessen EW, Muijtjens AMM, Van Gaal LF, Bossaert LL, De Winter BY (2009) Portfolio assessment during medical internships: how to obtain a reliable and feasible assessment procedure? Educ Health 22(3). http://www.educationforhealth.net/publishedarticles/article_print_313.pdf. Accessed 19 May 2011 [PubMed]

- 7.Miller GE. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Acad Med. 1990;65:S63–S67. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199009000-00045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Norcini JJ, McKinley DW. Assessment methods in medical education. Teach Teacher Educ. 2007;23:239–250. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2006.12.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tabish SA (2009) Assessment methods in medical education. Editorial. Int J Health Sci 4(2) No 2 (2). http://ijhs.org.sa/index.php/journal/issue/view/5. Accessed 22 May 2011

- 10.Albino J et al. (2009) Assessing dental students’ competence: best practice recommendations in the performance assessment literature and investigation of current practices in predoctoral dental education. J Dent Educ 72(12):1405–1435 [PubMed]

- 11.Holsgrove G, Davie H. Assessment in foundation program. Chapter 3. In: Jackson N, Jamieson A, Khan A, editors. Assessment in medical education and training: a practical guide. New York: Oxford; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Toolbox of Assessment Methods© (2000) Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), and American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS). Version 1.1. http://www.cpass.umontreal.ca/documents/pdf/mesure/reference/1.ABMS_Toolbox.pdf. Accessed 20 May 2011

- 13.Tochel C, Haig A, Hesketh A, Cadzow A, Beggs K, Colthart I, Peacock H. The effectiveness of portfolios for post-graduate assessment and education: BEME Guide No. 12. Med Teach. 2009;31(4):299–318. doi: 10.1080/01421590902883056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Challis M. AMEE Medical Education Guide No. 11 (revised): portfolio-based learning and assessment in medical education. Med Teach. 1999;21(4):370–386. doi: 10.1080/01421599979310. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rees C. The use (and abuse) or the term portfolio. Med Educ. 2005;39:436–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arter JA, Spandel V (1992) Using portfolios of student work in instruction and assessment. Educ Meas 11(1):36–44. http://www.ncme.org/pubs/items/18.pdf. Accessed 23 May 2011

- 17.Wiggins G. Assessment: authenticity, context, and validity. Phi Delta Kappan. 1993;75(3):200–208. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chambers DW, Glassman P. A primer on competency-based evaluation. J Dent Educ. 1997;61:651–666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Plaza CM, Draugalis JLR, Slack MK, Skrepnek GH, Sauer KA (2007) Use of reflective portfolios in health sciences education. Am J Pharm Educ 71(2):34,1–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Al-Shehri A. Learning by reflection in general practice: a study report. Educ Gen Pract. 1995;7:237–248. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davis MH, Ponnamperuma GG (2005) Portfolio assessment. J Vet Med Educ 32(3):279–284. http://www.utpjournals.com/jvme/tocs/323/279.pdf. Accessed 3 May 2011 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Wass V, Van der Vleuten C, Shatzer J, Jones R. Assessment of clinical competence. Lancet. 2001;357(9260):945–949. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04221-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Sullivan P, Cogbill KK, McClain T, Reckase MD, Clardy JA. Portfolio as novel approach for residency evaluation. Acad Psychiatry. 2002;26:173–179. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.26.3.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Definition of rubric as per Wikipedia. Available at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rubric_%28academic%29. Accessed 20 Mar 2012

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.