Abstract

Anaphylaxis is a medical emergency. Virtually, any individual may develop hypersensitivity to any of the various formulations/substances used in dental practice and this necessitates all dental professionals to keep themselves updated with the latest guide-line on management of life threatening anaphylaxis. Guidelines by the World Allergy Organization for the assessment and management of anaphylaxis in 2011 are discussed.

Keywords: Anaphylaxis, Medical emergency, Hypersensitivity, Dental, Dentist

Medical emergencies in a dental office are rare, but when it occurs, can be detrimental. The common medical emergencies faced by a dental professional have been reported to occur at 0.7 cases per dentist per year or on an average of once every 3–4 years [1]. Anaphylaxis is one such dreaded medical emergency. The term anaphylaxis is derived from the Greek terms “ana” meaning backward and “phylaxis” meaning guarding or protection [2]. It is an immune response, an individual develops, due to backward (previous) exposure to an allergen. Portier and Richet [3] are credited with this discovery and also proposed the term “anaphylaxis”. Anaphylaxis is an amplified, harmful immunologic reaction that occurs after re-exposure to an antigen to which an organism has become sensitive [4]. There have been reports that patients receiving dental care are allergic to commonly used pharmaceutical agent or substances used in dental practice. Hypersensitivity reactions to beta-lactam antibiotics are commonly encountered. It is found that 10 % of the population have true allergy to beta-lactams [5, 6]. Patients allergic to penicillins may also show a similar response to cephalosporins [7]. The frequency of anaphylactic allergic reactions to cephalosporins is reported to occur between 0.2 and 17 % and the cross-reactivity between cephalosporins and penicillins range from 0.1 to 14.5 % [8]. There have been reports of anaphylactic and anaphylactoid reactions to aspirin and other NSAIDs group of drugs, which are the backbone of pain management in dental practice. It is documented that NSAIDs may function as haptens capable of inducing allergic sensitization [9]. In a report by van Puijenbroek et al. [10] the use of NSAIDs, particularly diclofenac, ibuprofen, and naproxen showed relative high risk of developing an anaphylactic reactions. Local anesthetic agents, which remain an integral part of dental practice, have been associated with the risk of developing severe allergic reactions. True allergic reactions to local anesthetics are rare and represent less than 1 % of all adverse local anesthetic reactions, but when they occur, they may be life-threatening [11]. Allergic reactions to the amide local anesthetics are extremely rare and may be due to the preservative methylparaben which is an ester. Methylparaben has been removed from the carpules in the US, but is still used in the multiple dose vials in many countries. Sodium bisulfite is also a potential allergen that is used to prevent the oxidation of epinephrine in carpules that contain local anesthetic with epinephrine as a vasoconstrictor [11, 12]. Recently, there have been reports of severe hypersensitivity to preparations containing povidone iodine [13]. Products containing latex can also precipitate a life-threatening anaphylaxis [14]. Reports of allergic reactions to natural rubber latex have been increasing both among dental personnel and patients [15].

Virtually, any individual may develop sensitivity to any of the various formulations/substances used in dental practice and this necessitates that all dental professionals keep themselves updated with the latest guide-line on management of life threatening anaphylaxis [16]. World Allergy Organization has issued guidelines for the assessment and management of anaphylaxis in 2011 [17]. The recommendations in the guidelines are based on the clinical evidence available and are supported by anaphylaxis related citation of 150 references published by the end of 2010.

The clinical criteria in the proposed guidelines for the diagnosis of anaphylaxis include symptoms involving more than one body organ system (most of the time). At instances, when there is exposure to a known trigger for the patient, the diagnosis can be made when symptoms suddenly develop in only one organ system. Anaphylaxis is highly suggestive when any one of the following three criteria is fulfilled: 1. Acute onset of an illness with involvement of the skin, mucosal tissue, or both with either respiratory compromise or reduced blood pressure/symptoms of end-organ dysfunction; 2. Two or more of the following after exposure to a likely allergen in minutes to hours: involvement of the skin-mucosal tissue, respiratory compromise, reduced blood pressure, gastrointestinal symptoms.; 3. Reduced blood pressure after exposure to known allergen. Skin/mucosal involvement may present as urticaria, itching, flushing, swollen lips, tongue or uvula. Respiratory involvement may present as dyspnoea, wheeze-bronchospasm, stridor, reduced peak expiratory flow, hypoxemia. The end-organ dysfunction may manifest as hypotonia, syncope, incontinence. Gastrointestinal symptoms may include abdominal cramps, pain, vomiting etc. For adults, systolic blood pressure of less than 90 mmHg or greater than 30 % decrease from the baseline is of significance. Laboratory investigations that may aid in confirming the diagnosis of anaphylaxis include serum tryptase, histamine and its metabolite N-methylhistamine in urine samples. These tests are not performed on emergency basis and their negativity cannot rule out anaphylaxis [17].

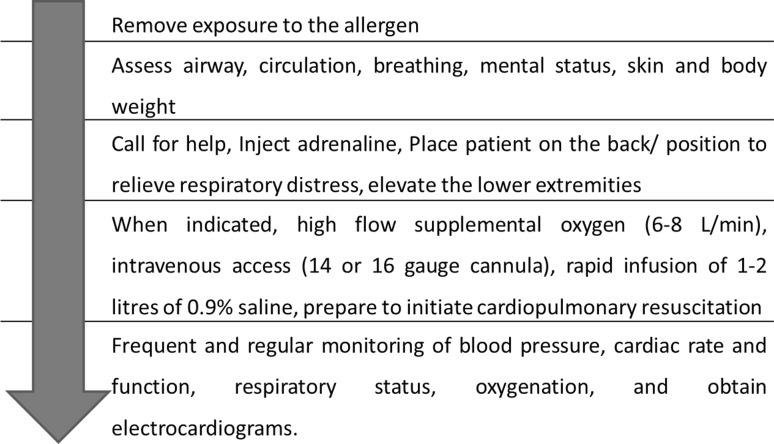

Adrenaline remains the first line medication for anaphylaxis treatment and is also classified under priority medication in the recommended guidelines. The recommended dosage for 1:1,000 (1 mg/mL) adrenaline is 0.01 mg/kg to a maximum of 0.5 mg for adults and 0.3 mg for children via intramuscular route of administration. If required, the dose can be repeated in 5–15 min. Intramuscular route of administration (preferred over subcutaneous) is recommended in the guidelines as skeletal muscles are well-vascularized and adrenaline has a dilator effect on this vasculature, facilitating a rapid absorption in the central circulation. Vastus lateralis muscle in mid-anterolateral thigh should be preferred for the intramuscular administration (Table 1). Second line medications for anaphylaxis include H1-antihistamine (chlorpheniramine, diphenhydramine etc.), β2-adrenergic agonists (salbutamol), glucocorticoids (hydrocortisone), H2-antihistamines (ranitidine) [17]. The stepwise protocol for management of an anaphylaxis case is summarized in Fig. 1.

Table 1.

Recommendations for adrenaline use in anaphylaxis

| Adrenaline administration |

|---|

| Inject epinephrine/adrenaline intramuscularly in the mid-anterolateral aspect of the thigh |

| 0.01 mg/kg 1:1,000 (1 mg/mL) solution to a maximum of 0.5 mg for adults and 0.3 mg for children (consider child: <35–40 kg body weight) |

| Record the time of the dose and if required, repeat it in 5–15 min |

Fig. 1.

Protocol for anaphylaxis management

The recommendation in the guidelines emphasize that the ‘prompt basic initial treatment’ is life-saving in cases where anaphylaxis is recognized. The evidence on acute anaphylaxis management lack randomized controlled trials of any therapeutic interventions in practice, and should be the focus of research to strengthen the treatment protocols.

References

- 1.Resuscitation Council UK (2011) Standards for clinical practice and training for dental practitioners and dental care professionals in general dental practice. ISBN 1 903812-15-1

- 2.James JS. Anaphylaxis: multiple etiologies—focused therapy. J Ark Med Soc. 1996;93(6):281–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Portier P, Richet C. De l’action anaphylactique de certains venins. Comptes Rendus de la Societe de Biologie (Paris) 1902;54:170–173. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Noone MC, Osguthorpe JD. Anaphylaxis. Otolaryngol Clin N Am. 2003;36:1009–1020. doi: 10.1016/S0030-6665(03)00062-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Solensky R. Hypersensitivity reactions to beta-lactam antibiotics. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2003;24(3):201–220. doi: 10.1385/CRIAI:24:3:201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Devadoss P, Bhargava D. Periorbital edema following per-oral amoxicillin administration. Streamdent. 2011;2(1):7–8. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hameed TK, Robinson J. Review of the use of cephalosporins in children with anaphylactic reactions from penicillins. Can J Infect Dis. 2002;13(4):253–258. doi: 10.1155/2002/712594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Atanaskovic-Markovic M, Nestorovic B. Allergy to cephalosporin antibiotics in childhood. Srp Arh Celok Lek. 2003;131(3–4):127–130. doi: 10.2298/SARH0304127A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berkes EA. Anaphylactic and anaphylactoid reactions to aspirin and other NSAIDs. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2003;24(2):137–148. doi: 10.1385/CRIAI:24:2:137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Puijenbroek EP, Egberts AC, Meyboom RH, Leufkens HG. Different risks for NSAID-induced anaphylaxis. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36(1):24–29. doi: 10.1345/aph.1A140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Speca SJ, Boynes SG, Cuddy MA. Allergic reactions to local anesthetic formulations. Dent Clin N Am. 2010;54(4):655–664. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malamed SF (2004) Handbook of local anesthesia, 5th edn. St Louis (MO), Elsevier Mosby

- 13.Ono T, Kushikata T, Tsubo T, Ishihara H, Hirota K. A case of asystole following povidone iodine administration. Masui. 2011;60(4):499–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spina AM, Levine HJ. Latex allergy: a review for the dental professional. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1999;87(1):5–11. doi: 10.1016/S1079-2104(99)70286-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Field EA, Longman LP, Al-Sharkawi M, Perrin L, Davies M. The dental management of patients with natural rubber latex allergy. Br Dent J. 1998;185(2):65–69. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4809730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rochford C, Milles M. A review of the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of allergic reactions in the dental office. Quintessence Int. 2011;42(2):149–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simons FE, Ardusso LR, Bilò MB, El-Gamal YM, Ledford DK, Ring J, Sanchez-Borges M, Senna GE, Sheikh A, Thong BY. World Allergy Organization anaphylaxis guidelines: summary. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(3):587–593. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]