Abstract

Background

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) serve signaling functions in the vasculature, and hypoxia has been associated with increased ROS production. NADPH oxidase 4 (Nox4) is an ROS-producing enzyme that is highly expressed in the endothelium, yet its specific role is unknown. We sought to determine the role of Nox4 in the endothelial response to hypoxia.

Methods and Results

Hypoxia induced Nox4 expression both in vitro and in vivo and overexpression of Nox4 was sufficient to promote endothelial proliferation, migration, and tube formation. To determine the in vivo relevance of our observations, we generated transgenic mice with endothelial-specific Nox4 overexpression using the VE-cadherin promoter (VECad-Nox4 mice). In vivo, the VECad-Nox4 mice had accelerated recovery from hind limb ischemia and enhanced aortic capillary sprouting. Because endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) is involved in endothelial angiogenic responses and eNOS is activated by ROS, we probed the effect of Nox4 on eNOS. In cultured ECs overexpressing Nox4 we observed a significant increase in eNOS protein expression and activity. To causally address the link between eNOS and Nox4 we crossed our transgenic Nox4 mice with eNOS-/- mice. Aorta from these mice did not demonstrate enhanced aortic sprouting and VECad-Nox4 mice on the eNOS-/- background did not demonstrate enhanced recovery from hind limb ischemia.

Conclusions

Collectively, we demonstrate that augmented endothelial Nox4 expression promotes angiogenesis and recovery from hypoxia in an eNOS-dependent manner.

Keywords: NADPH oxidase 4, Reactive Oxygen Species, Endothelium, Angiogenesis, Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase

Introduction

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as superoxide anion (O2·-) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) have been linked to the onset and progression of cardiovascular disease, yet antioxidant strategies to reduce ROS levels have failed to limit cardiovascular events.1 Thus, ROS levels alone are not a determinant of pathology, suggesting that the role of ROS in disease processes is complex. One reason that ROS may have unpredictable consequences in the vasculature is that they also serve as second messengers in multiple cellular processes such as proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis.2 In addition, ROS are important for cytoskeletal rearrangement and cell migration in response to angiogenesis-inducing growth factors, including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)3,4 and angiopoietin-1.5 Thus, there is evidence that ROS are involved in vascular physiology.

Tissue ischemia and the resultant hypoxia initiate a tightly regulated response that includes both cellular adaptation and efforts to improve oxygen delivery, such as angiogenesis. Evidence now indicates that the response to hypoxia is dependent, in part, on ROS production. For example, the up-regulation of VEGF and VEGF receptors is linked to a concomitant increase in ROS production during hypoxia.6 Ligand engagement of the VEGF receptor results in ROS production7 and exogenous application of ROS promote endothelial responses that mimic angiogenesis such as increased cell proliferation, migration, and tube formation.8 The specificity of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α), the master regulator of hypoxia-induced genes, is derived from protein stabilization due to an ROS flux during hypoxia, that is absent in anoxia.9,10 Thus, ROS are clearly involved in signaling responses important for angiogenesis. However, the specific ROS sources that mediate these physiologic events are not completely defined.

Many members of the NADPH oxidase (Nox) enzyme family are expressed in the vasculature and produce ROS in response to environmental cues. In general, these enzymes are governed by the activity of accessory proteins that facilitate full enzyme activity via the transfer of NADPH-derived electrons to molecular oxygen, initially resulting in superoxide formation.11 Among the Nox family, the Nox4 isoform is unique in that it requires little regulation from accessory proteins and primarily releases H2O2 into the cytosol. 12-15 Multiple lines of evidence suggest that Nox4 is involved in the adaptation to hypoxia as it is upregulated in tissue ischemia,16-19 and Nox4 inhibition prevents endothelial-derived tumor formation.20 The vascular endothelium contains abundant Nox421,22 and this oxidase mediates endothelial responses to TGFβ23 and EGF,24 that include migration and proliferation. Despite these data linking Nox4 to hypoxic responses, its specific role is not yet known and thus, we sought to identify the implications of endothelial Nox4 in the adaptation to hypoxia.

Methods

Cell culture

Cultured human and bovine ECs were obtained from Lonza (Basel, Switzerland) and used between passages 3 and 8. Human cells were cultured in EGM-2 containing 2% FBS and bovine cells were cultured in EGM with 5% FBS with the included bullet kit supplements (Lonza). Mouse lung endothelial cells (MLECs) were harvested via 2 consecutive selections using ICAM-2 and cultured on 0.2% gelatin-coated dishes in EGM-2 culture medium containing 10% FBS. The cells were used for experiments between passages 2-6.

Adenoviral constructs

The adenoviral vector expressing Nox 4 was a gift from Dr. Barry Goldstein (Thomas Jefferson University).25 The adenoviral vector expressing Nox4 RNAi (Nox4i) was constructed as described in Chen et al..24 Cells were typically infected at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 to 50 with a control adenovirus at the same MOI. For in vivo administration of adenovirus: three days prior to surgery either LacZ or Nox4 adenoviral constructs (2 × 108 pfu) were injected into 5 sites of the thigh adductor muscle.

PCR

Total RNA was extracted using Qiagen RNeasy© mini kits for cells and using TRIzol (Invitrogen) for tissue samples according to the manufacturer's protocol. Total RNA was reverse-transcribed to cDNA using QIAGEN Omniscript RT Kit at 37°C for 60 minutes. The primers used for PCR were: Nox4 fwd: tacctccgaggatcacagaa; Nox4 rev: gaatctgggctcttccatac; Nox2 fwd: tgcgtgctgctcaacaagag; Nox2 rev: ggagggtttccagcaaactg; Nox1 fwd: gcgtctgctctctgctttaa; No×1 rev: agcaacgctggtgaatgtca and GAPDH fwd: acagtccatgccatcactgcc GAPDH rev: aggaaatgagcttgacaaagt; 18S fwd: cggctaccacatccaaggaa 18S rev: gctggaattaccgcggct. The real-time PCR primers used were: hNox4 fwd:cagaaggttccaagcaggag and hNox4 rev: gttgagggcattcaccagat; GAPDH fwd: acccagaagactgtggatgg and GAPDH rev: aggccatgccagtgagctt. For mouse muscle Nox4 expression: mNox4 fwd: acttttcattgggcgtcctc and mNox4 rev: gaactgggtccacagcaga and the signal was normalized to mouse HPRT1 fwd: tggccatctgcctagtaaagc and rev: ggctcatagtgcaaatcaaaagtc. The real-time PCR reactions were run on a Bio-RAD iQ5 iCycler.

Determination of ROS

As an index of ROS generation, we used the Amplex Ultra Red reagent, 10-acetyl-3,7-dihydroxyphenoxazine (Molecular Probes; A36006) that reacts with hydrogen peroxide (1:1 stoichiometry) in the presence of horseradish peroxidase (HRP) to form resorufin. Endothelial cells were cultured to confluence in 12-well plates and incubated with Kreb's HEPES buffer (118mM NaCl, 22mM HEPES, 4.6mM KCl, 2.1 mM MgSO4, 0.15mM Na2HPO4, 0.41mM KH2PO4, 5mM NaHCO3, 5.6mM Glucose, 1.5mM CaCl2) for 30min. The Amplex Ultra Red and HRP was then added and fluorescence (excitation 544 nm; emission 590 nm) determined as a function of time (2h) in 96-well black plates (Corning) at 37°C in a fluorescent plate reader (Spectramax, Molecular Devices).

Endothelial tube formation and migration

We utilized the spontaneous organization of ECs into capillary-like tubules when grown in vitro on Matrigel. Cells were cultured alone or with adenoviral constructs for 24h. Cells were then trypsinized and plated on Matrigel and monitored over time (6-12h) for tube formation as described. At least 5 random fields of vision were then analyzed for tube length using NIH Image J software for quantification. For migration, we utilized the scratch assay. Bovine aortic endothelial cells (BAECs; Lonza) were infected with LacZ, Nox4, or Nox4i adenovirus for 48h. Cells were then treated with 50μg/mL mitomycin C to inhibit proliferation and scratched with a 200μL pipet. Migration was quantified as the extent of gap closure with NIH Image J software.

Generation of endothelial-specific Nox4 transgenic mice

Full-length of human Nox4 cDNA was subcloned into the pCR3.1 vector (Invitrogen) followed by restriction digestion with KpnI and XhoI. The resultant fragment was inserted into the NotI site between the mouse VE-cadherin promoter and the SV40 polyadenylation sequence of the pBSmVE vector26 and the resultant construct confirmed by sequencing. A linearized DNA fragment containing the intact mouse VE-cadherin promoter – hNox4 – SV40pA cassette was used for pronuclear injection to generate multiple founders with endothelial-specific expression of hNox4 in the C57/Bl6 background (University of Massachusetts Transgenic Core Facility). The primers used for genotyping are: 5′-cta tct gca ggc agc tca ca-3′ and 5′- gat gaa cag gca gag gtg tt-3′.

In Situ hybridization

To detect human Nox4 expression specifically, a 750bp probe was designed that contained 530bp of the human Nox4 sequence and 220 bp of the VE-Cad vector. The fragment was cloned into pBluescript SK (Stratagene) and riboprobes were synthesized following the Digoxigenin (DIG) labeling manufacturer protocol (Roche). Slides (14μm cryosection) were incubated with probe overnight at 50°C, blocked with maleic acid butter with Tween 20 (MABT)/2% blocking reagent (Roche)/20% sheep serum at room temperature for 2-3hrs and anti-DIG alkaline phosphatase (AP) was then added to the slides (1:3000 dilution) followed by incubation overnight at 4°C. Slides were then stained with 5-Bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate/Nitro-blue (BCIP/NBT) (3.5μl/ml) overnight at 37°C and images were obtained using a 40 × 1.30 objective (Nikon) on an inverted microscope (TE-2000; Nikon) with a camera (Cool-SNAP HQ; Photometrics). Images were captured using NIS-Elements software (Nikon).

Immunofluorescence

Aorta were perfused with 4 mL of 0.9% sterile saline solution prior to excision and removal of perivascular fat and adventitia using a dissecting microscope. Tissue was then formalin fixed for 12h and paraffin embedded. Nox4 antibody (Novus) was diluted 1:50 and VWF was diluted 1:100 (abcam). Secondary antibodies (Fluor488 or Fluor594 tagged goat anti– rabbit or donkey anti-sheep IgG; Invitrogen) were diluted 1:200. Fluorescence images were obtained using a 20 × 1.30 objective on the inverted microscope system described above.

Capillary sprouting

The aorta were perfused and cleaned as described above, then 1mm segments were placed in 300μL cold Matrigel in a 48 well plate. After 30min in 37°C incubator, EBM-2 media/10% FBS were added and the media changed every other day. Capillary sprouting was counted by phase-contrast microscopy using at least 6 segments of aorta from four mice/group. Aortic ring sprouts were carefully analyzed based on morphological differences in growth between the endothelial sprouts and fibroblast sprouts based on greater thickness and a uniform pattern of growth. Sprout counting was confirmed with CD31 staining (data not shown).

Hindlimb ischemia and laser Doppler imaging

Animals were anesthetized with Ketamine (100mg/kg) and Xylazine (20mg/kg) via intraperitoneal injection and placed on a heated water blanket to maintain body temperature. The left femoral artery was exposed via an inguinal incision (1.5 – 2 cm) and the femoral artery was ligated and removed from its origin to the proximal portion of the saphenous artery (along with the adjacent veins). For eNOS-/- animals, the femoral artery and vein were simply ligated (5.0 nylon suture) at the origin to prevent limb loss.27 Animals underwent periodic assessment of blood flow using laser Doppler imaging (a non-invasive technique that allows a user to monitor how the perfusion gradually recovers over time) as described.28

Immunohistochemistry

Ischemic and nonischemic muscle was removed and immediately frozen in Tissue Tek OCT and sections (7μM) were subsequently stained with antibody to platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (CD31: BD Pharmingen) and counterstained with hematoxylin and eosin. Cells positive for CD31 antigen were counted using phase contrast microscopy with at least 4 different microscopic fields from each animal and capillary density was expressed as the capillary number/muscle fiber (40×) or as normalized to nonischemic capillary density per field of vision (20×). Images were obtained using the inverted microscope system described above.

Isometric measurements of endothelial function

Thoracic aortic rings (2 mm in length) were mounted on 200 μM pins in a 6-mL vessel myograph (Danish Myo Technology) containing physiological salt solution (PSS): 130mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 1.18mM KHPO4, 1.17 mM MgSO4, 1.6 mM CaCl2, 14.9 mM NaHCO3, 5.5 mM dextrose, 0.03 mM CaNa2/EDTA. Vessels were stretched to 1g basal tension at 37°C and aerated with 95% O2-5% CO2. Vessels were equilibrated in PSS for 1h, followed by two consecutive contractions with PSS containing (60 mM potassium) and 1 μM phenylephrine (PE), then with KPSS alone. Rings were then washed, allowed to return to basal tension, and subjected to concentration-response curves to PE.

cGMP Measurement

To measure cGMP in vitro, we cultured human aortic endothelial cells (HAECs) +/- adenoviral constructs and rat aortic smooth muscle cells (RaSMCs) to confluence in 6-well plates. Cells were then washed 2×with Locke's buffer (154mM NaCl, 5.6mM KCl, 2mM CaCl2, 1mM MgCl2, 10mM HEPES; pH 7.4) and allowed to equilibrate in Locke's buffer containing 200 μM 3-isobutyl-1- methylxanthine (IBMX), 100 U/mL superoxide dismutase (SOD), and 200 μM L-arginine for 30min. The calcium ionophore (A23187; 10μM; Sigma) was then added to the stimulated wells of the HAECs for 30min. Immediately the endothelial bathing media was transferred to the RaSMCs for 3 minutes. The reaction was stopped with the immediate removal of buffer and addition of ice-cold 5% trichloroacetic acid (TCA). cGMP was measured using commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits according to manufacturer's instructions (Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI). Results are expressed as normalized to the adenoviral untreated control of 3 separate experiments run in triplicate.

To measure tissue cGMP, aorta were removed and cleared of connective tissue as described above. Aortic rings of 2 mm width were cut and placed into individual wells of a 96 well plate with 100 μL of DMEM with 10% FBS and 500μM IBMX + 200uM L-arginine. Aortic rings were allowed to equilibrate for 30 minutes and then fresh media was added +/- 500 μM N-Nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) and incubated for 20 minutes. Aorta were then snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and immediately placed in ice-cold 0.1M HCl and homogenized. Samples were diluted 1:3 and cGMP was measured using commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit according to manufacturer's instructions (Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI). At least 3 segments in each condition from 4 mice/group were measured.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean ± SEM. Images shown are representative of three or more independent experiments. Comparisons among two treatment groups were performed with a Student's t-test, whereas comparisons amongst three or more groups involved one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a post hoc Dunnet's comparison. Dose-response curves were compared using two-way ANOVA with or without repeated measures as appropriate. Statistical significance was accepted if the null hypothesis was rejected with p < 0.05.

Results

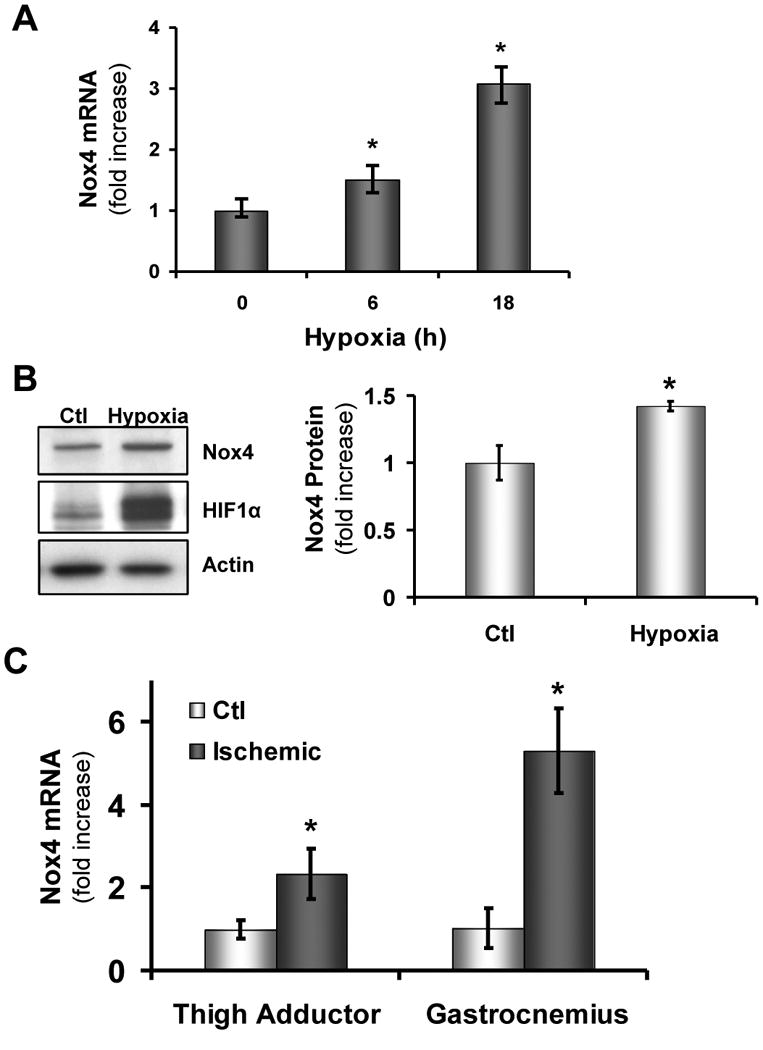

Hypoxia upregulates Nox 4

To examine if Nox4 regulation is a part of the cellular hypoxic response, cultured endothelial cells (ECs) were subjected to hypoxia (1% oxygen) and we observed a marked increase in Nox4 mRNA and protein expression coincident with HIF1α upregulation (Figures 1A and B ). We did not see increased expression of other Nox isoforms (supplementary Figure 1A). We then probed the in vivo relevance of these observations in wild-type C57/Bl6 mice with hind limb ischemia and found increased Nox4 expression in ischemic gastrocnemius (5-fold) and thigh adductor muscles (2-fold) compared with non-ischemic muscle (Figure 1C; p < 0.05 n = 4). Thus, hypoxia is associated with Nox4 upregulation in vitro and in vivo.

Figure 1. Nox4 is upregulated in hypoxic conditions.

Human aortic endothelial cells (HAECs) were plated in 6-well plates and placed in a hypoxic chamber (1% O2). Cells were immediately harvested for RNA analysis as described in Methods and analyzed with real-time PCR (*p < 0.05 vs. 0h; n = 3) (A) or (B) immediately lysed on ice and subsequently probed by western blot for changes in protein expression as indicated (*p < 0.05 vs. Ctl; n = 3). (C) Wild-type (WT; C57/Bl6) mice underwent hindlimb ischemia (as in Methods) and after 48h muscle tissue was harvested from the right (Ctl) and left (Ischemic) thigh adductor and gastrocnemius muscles (*p < 0.05 vs. Ctl; n = 4) .

Nox4 stimulates angiogenesis

Previously we have shown that Nox4 overexpression potentiates endothelial proliferation.24 To determine if Nox4 also drives EC behaviors important for angiogenesis, we overexpressed or knocked down Nox4 using Nox4 and Nox4i adenovirus in ECs (supplementary Figure 1B-D) under conditions that do not impact Nox2 expression (supplementary Figure 1B) and examined EC tube formation and migration. Under basal conditions, increasing Nox4 expression alone increased endothelial tube formation (Figure 2A) and migration (Figure 2B). Conversely, with knockdown of Nox4, we observed blunted tube formation (Figure 2C) and migration (Figure 2D). To examine the role of ROS in Nox4-mediated tube formation, we overexpressed Nox4 in ECs and found that the antioxidants taxifolin (250 μM) and polyethylene glycol (PEG)-catalase (200 U/mL) decreased Nox4-induced tube formation (Figure 2E). Thus, Nox4 promotes angiogenesis in an ROS-dependent manner.

Figure 2. Nox4 expression promotes ROS-dependent endothelial migration and tube formation.

HAECs were treated with LacZ or Nox4 adenovirus as above for 24h then trypsinized and plated on Matrigel for 6h and tube formation was imaged and quantified using NIH Image J software to assess tube length (A). (B) Bovine aortic endothelial cells (BAECs) were treated with Lac Z (Ctl) or Nox4 adenovirus for 24h. Confluent cells were then scratched with a 200μL pipet and cell migration was imaged after 8h. Gap closure was quantified at 8h using NIH image J software. (C) HAECs were treated with scrambled (Ctl) or Nox4 siRNA (Nox4i) adenovirus for 48h and then plated on Matrigel for 6h prior to imaging for tube formation as above. (D) BAECs were treated for 48h with Nox4i as above and then scratched as in B and imaged after 24h. (E) HAECs were treated with Nox4 adenovirus as in (A) and then plated on Matrigel with or without taxifolin (250μM) or PEG-catalase (200U/mL) and assessed for tube formation at 6h. *p<0.05 vs. Nox4 by one-way ANOVA with a post hoc Dunnet's test. For all other comparisons, *p < 0.05 vs. Ctl by Student's t-test with N=3 for 3 for each group.

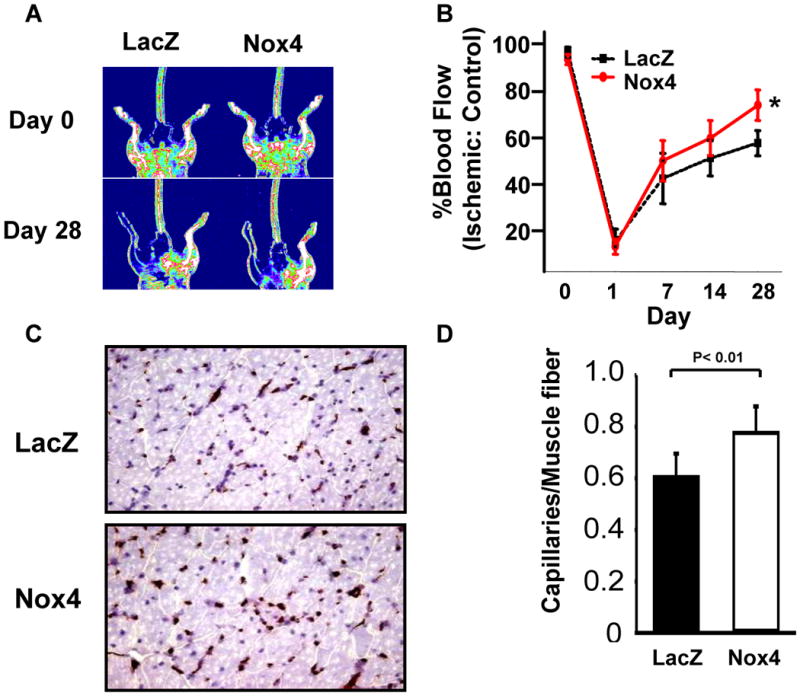

We then probed the in vivo consequences of acute Nox4 overexpression utilizing a hindlimb ischemia-induced angiogenesis model.28 We observed enhanced blood flow recovery in mice receiving local adenoviral Nox4 injection compared to LacZ injection (Figures 3A and 3B). Blood flow recovery reflected increased capillary density determined by CD31 staining of muscle tissue (Figures 3C and 3D). Thus, these data support the notion that Nox4 stimulates angiogenesis.

Figure 3. Nox4 improves recovery from hindlimb ischemia in C57/Bl6 mice.

C57/Bl6 mice underwent hindlimb ischemia as in Methods. Three days prior to surgery LacZ or Nox4 adenovirus (2 × 108 pfu) were injected into 5 sites of the thigh adductor muscle. Mice were monitored for return of blood flow using laser Doppler imaging (A) and recovery was quantified as % blood flow return in ischemic vs. control leg (B; *p < 0.05 vs. LacZ by two-way repeated measures ANOVA, n = 6/group). (C) At day 28 mice were sacrificed and gastrocnemius muscle was stained for CD31. (D) Composite data of CD31 positive capillaries/muscle fiber is shown.

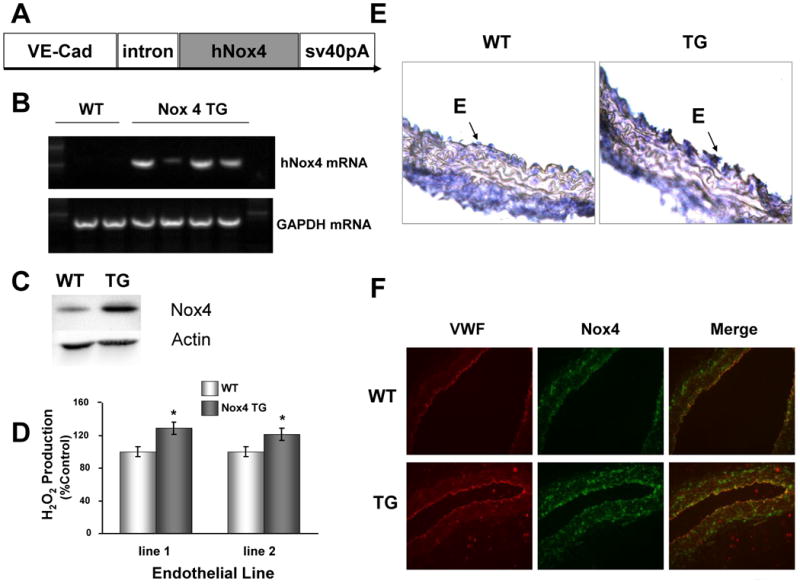

Generation of endothelial specific Nox4 transgenic mice

To determine if endothelial Nox4 expression is sufficient to stimulate angiogenesis, we created transgenic mice harboring the human Nox4 gene under control of the vascular endothelial cadherin (VE-Cad) promoter (VE-Cad-Nox4; Figure 4A). Mouse lung endothelial cells (MLECs) were harvested from wild-type and multiple transgenic animals that exhibited increased Nox4 mRNA (Figure 4B) and protein (Figure 4C). We then assayed ROS production in MLECs from two lines of transgenic animals versus control mice and observed a 20-30% increase in hydrogen peroxide production as assessed by Amplex Ultra Red reagent (Figure 4D). In aortic sections from the WT and VE-Cad-Nox4 mice we observed increased Nox4 mRNA (Figure 4E) and protein (Figure 4F) expression. We then removed the endothelium from the aorta (detergent perfusion) which is a small percentage of the total aortic tissue and compared this to lung (highly endothelialized) tissue from the same mice and demonstrated clear mRNA overexpression in the TG lung tissue which was not seen in the de-endothelialized aorta (Supplementary Figure 2A). We also assessed lung tissue expression in both young (3 mos) and old mice (1 year) and found sustained increased expression at both the mRNA and protein levels (Supplementary Figure 2B and 2C).

Figure 4. Endothelial specific Nox4 overexpression.

(A) Construct for creation of endothelial-specific human Nox4 overexpression (VE-Cad = vascular endothelial cadherin, SV40pA = SV40 polyadenylation sequence). Mouse lung endothelial cells (MLECs) were harvested from wild type (WT) and Nox4 transgenic (TG) mice and human Nox4 mRNA (B) and protein (C) expression confirmed by RT-PCR and immunoblot, respectively. (D) MLECs from two distinct TG founder lines were assessed for extracellular H2O2 production using Amplex red (*p < 0.05; n = 3). (E) Segments of WT and Nox4 TG aorta were isolated, fixed, and assessed for Nox4 gene expression using in-situ hybridization (40×). (F) Aortic segments from WT and TG mice were fixed and paraffin embedded and co-stained with VWF, an endothelial marker and Nox4 for immunofluorescence (20×).

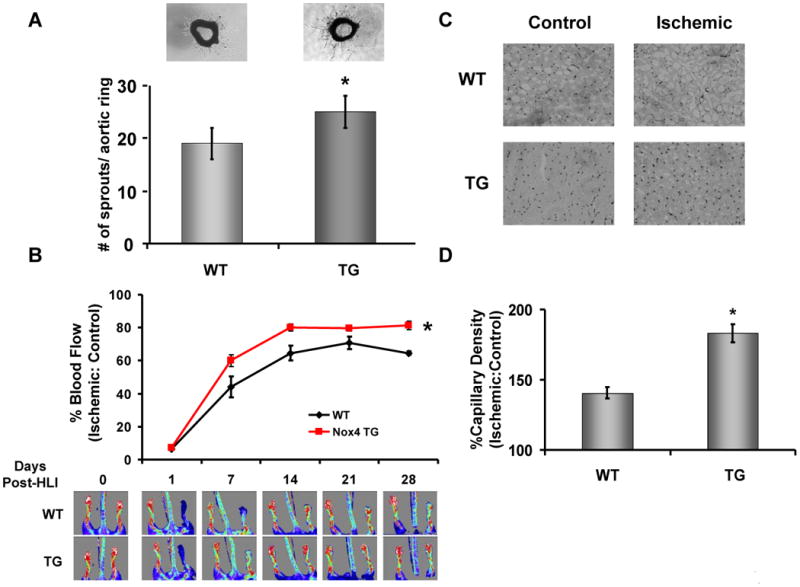

Endothelial Nox4 is sufficient to promote angiogenesis

We probed capillary sprouting from intact aorta as a model of early angiogenesis. Aorta from VE-Cad-Nox4 mice demonstrated enhanced ex vivo capillary sprouting compared to wild-type littermates (Figure 5A). To evaluate the physiologic relevance of this observation, we utilized the hind-limb ischemia model and found blood flow recovery after femoral artery excision was significantly hastened in VE-Cad-Nox4 mice compared to littermate controls (Figure 5B). Consistent with increased angiogenesis, there was increased capillary density in gastrocnemius muscle harvested from VE-Cad-Nox4 compared to wild-type animals (Figure 5C and 5D).

Figure 5. Endothelial Nox4 overexpression promotes angiogenesis.

Aorta were removed from wild type (WT) and VE-Cad Nox4 transgenic (TG) littermates and cultured in Matrigel for 7d (A, top). Capillary sprouts were then counted in 6 separate aortic sections using bright-field microscopy (A, bottom, *p<0.05 by Student's t–test, n = 3 per group) (A). (B) Wild-type (WT) and VE-Cad Nox4 transgenic (Nox4 TG) mice were subjected to hind limb ischemia as in Methods and blood flow recovery monitored using laser Doppler imaging over 28d (*p<0.05 vs. WT by two-way ANOVA, n = 9 – 10/group). (C) At 28d gastrocnemius muscle was harvested from the control and ischemic legs of wild type (WT) and VE-Cad Nox4 transgenic (TG) animals and stained for CD31 as an index of capillary density (20× objective). (D) Composite data from C per 20× field (*p<0.05 by Student's t–test, n= 3/group).

Nox4 increases endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity and expression

Endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) is a key regulator of angiogenesis29 and there is evidence that ROS may regulate eNOS expression and activity30,31 Therefore we probed eNOS regulation by Nox4. In cultured ECs, Nox4 overexpression produced increased total eNOS expression and activity (Figure 6A). To further assess Nox4 activation of eNOS we measured cGMP accumulation in a co-culture system using human aortic endothelial cells (HAEC) and rat aortic smooth muscle cells (RaSMC). Under basal conditions we saw a 2-fold increase in cGMP production which was dramatically increased upon stimulation with the calcium ionophore A23187 (Figure 6B). To further probe the mechanisms of eNOS regulation by Nox4, we introduced catalase into our Nox4 overexpression system and observed an attenuation of both expression and phosphorylation of eNOS (Figure 6C), indicating Nox4-derived ROS were responsible for eNOS activation. Under hypoxic conditions adenoviral knockdown of Nox4 lead to a decrease of both total and Ser-1177 phosphorylated eNOS (Figure 6D).

Figure 6. Nox4 promotes eNOS activity.

(A) HAECs were infected with LacZ or Nox4 adenovirus for 24h, the cells lysed, and assessed for phosphorylated (Ser-1177; p-eNOS) and total eNOS as well as actin by immunoblotting. *p<0.05 vs. Ctl by Student's t-test; N=3. (B) HAECs and RaSMCs were co-cultured and assessed for cGMP accumulation as described in Methods. The left panel represents basal activity, whereas the right panel demonstrates the cells after stimulation with the calcium ionophone, A23187 (10μM). *p<0.05 by Student's t-test; N=3. (C) HAECs were infected with Nox4 alone or Nox4 with catalase for 48h and assessed for total and phosphorylated (Ser-1177) eNOS, catalase, and actin by immunoblotting. (D) HAECs were cultured for 18h in hypoxic conditions +/- Ad-Nox4i and probed for total and phosphorylated (Ser-1177) eNOS, Nox4 and actin by immunoblotting. (E) Aorta were harvested from wild-type (WT) and VE-Cad Nox4 transgenic (TG) mice and assessed cGMP accumulation (*p < 0.05 vs. WT by Student's t-test; n = 4). (F) Aorta were harvested from wild-type (WT) and VE-Cad Nox4 transgenic (TG) mice and assessed for contraction in response to phenylephrine (PE; *p<0.05 vs. WT by two-way repeated measures ANOVA, n = 7/group). (G) Aorta were harvested from eNOS-/- and VE-Cad Nox4 transgenic (TG) eNOS-/- mice and assessed for contraction in response to phenylephrine (n = 5/group).

Consistent with the observation that Nox4 enhances eNOS activity, aorta from VE-Cad-Nox4 TG mice demonstrated increased basal NO• production manifest as enhanced cGMP production (Figure 6E). This increase in basal eNOS activity appeared functional as intact aortic rings from VE-Cad-Nox4 mice exhibited less phenylephrine (PE)-induced contraction than vessels from littermate controls (Figure 6F). To further examine the role of basal NO• bioactivity we conducted functional aortic assays on VE-Cad Nox4 transgenic mice bred onto the eNOS-null (eNOS -/-) background and found no effect of Nox4 in the absence of eNOS (Figure 6G).

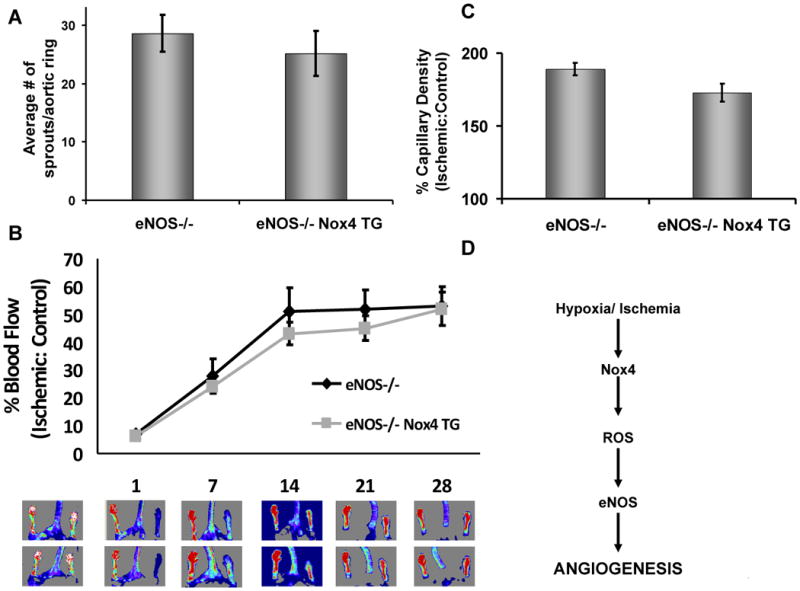

Nox4 stimulation of angiogenesis requires eNOS

To test the hypothesis that eNOS activation is required for Nox4-stimulation of angiogenesis in vivo, we utilized the VE-Cad Nox4 transgenic mice on the eNOS -/- background. In aorta from mice lacking eNOS, there was no difference in capillary sprouting as a function of the transgene (Figure 7A). Moreover, endothelial Nox4 overexpression no longer accelerated the recovery from hindlimb ischemia in mice lacking eNOS (Figures 7B and 7C). Collectively, these data demonstrate that Nox4 stimulation of angiogenesis requires eNOS (Figure 7D).

Figure 7. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) is necessary for Nox4 stimulation of angiogenesis.

VE-Cadherin Nox4 transgenic Nox4 mice were bred onto the eNOS-null (eNOS-/-) background to produce eNOS-/- Nox4 TG animals. (A) Aorta were harvested from eNOS-/- and eNOS-/- Nox4 TG mice and capillary sprouting assessed in Matrigel over 7d as in Fig. 5A (n=3). (B) We subjected eNOS-/- and eNOS-/- Nox4 TG mice to hindlimb ischemia and monitored blood flow recovery as in Fig. 5B (n=8-9/group). (C) Gastrocnemius muscle from control and ischemic limbs was harvested from animals treated as in B after 28d and capillary density assessed by CD31 immunostaining as in Fig. 5D (n=3/group). (D) Schematic of Nox4 adaptation to hypoxia.

Discussion

Our data demonstrate that hypoxia is associated with upregulation of Nox4 and that endothelial Nox4 is sufficient to promote angiogenesis in an eNOS-dependent manner. In cultured ECs and in vivo, hypoxia was associated with robust upregulation of Nox4, suggesting that Nox4 upregulation may be an adaptive response to tissue ischemia and hypoxia. The endothelium responds to ischemia by promoting angiogenesis and here we demonstrate that endothelial Nox4 upregulation was sufficient to promote many salient features of the angiogenic process. Specifically, endothelial proliferation, migration, and tube formation were promoted by Nox4 in an ROS-dependent manner. Importantly, these findings were physiologically relevant as Nox4 overexpression in vivo led to enhanced angiogenesis in response to hypoxia. The vascular endothelial cell appeared central in mediating this effect because endothelial-specific Nox4 overexpression promoted angiogenesis both in vitro and in vivo. Finally, we were able to demonstrate that the mechanism whereby Nox4 promotes angiogenesis was eNOS-dependent mediated by H2O2. Thus, our data implicate Nox4 as an important adaptive response to ischemia that coordinates the endothelial contribution to new vessel formation.

Data in the literature have demonstrated that Nox4 is upregulated in hypoxic settings such as ischemia and tumor angiogenesis. Ischemic brain injury is associated with an upregulation of Nox4 expression that corresponds temporally to the initiation of angiogenesis.18 These data, coupled with the fact that Nox4 expression is increased in newly formed capillaries, suggests that Nox4 is linked to angiogenesis. Moreover, hypoxia-induced tumor angiogenesis is associated with Nox4 upregulation32,33 and Nox4 suppression in ovarian cancer cells limits angiogenesis.32 Our data demonstrate a causal role for endothelial Nox4 in promoting angiogenesis as Nox4 overexpression is sufficient to promote key endothelial phenotypes (e.g. proliferation, migration, tube formation) and Nox4 knockdown hinders these processes that are important in new vessel formation. These findings were of physiological relevance as we found that mice with endothelial-specific Nox4 overxpression exhibited significant promotion of blood flow recovery in response to hind limb ischemia.

In multiple ischemia/reperfusion studies, excessive ROS production is known to cause tissue damage. However, in this study we observed a beneficial response with overexpression of an ROS-producing enzyme following hypoxia. How Nox4 promotes tissue repair rather than injury is not yet clear, but is likely related to the unique characteristics of the enzyme. For example, Nox4 releases H2O212-15 and this species is a two-electron oxidant well suited for cell signaling owing to its preferred target (thiols) and relatively longer half-life compared to other ROS such as superoxide.34 Moreover, Nox4 seems to generate ROS constitutively rather than producing a high-level burst as in the neutrophil enzyme, Nox2. It is plausible, therefore, that Nox4-derived ROS are not cytotoxic and, as a consequence, are involved in mediating reparative signaling.

Our data identifies eNOS as a downstream component of Nox4 signaling. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase and its production of bioactive NO• contributes to angiogenesis35 through enhancing EC proliferation and migration. 36,37 As a consequence, mice lacking eNOS exhibit a significant impairment in ischemia-induced angiogenesis.27 Given that pathological increases in vascular ROS are known to limit NO• bioactivity, 38 it is surprising that an ROS-producing enzyme promotes an NO•-dependent process. However, evidence in the literature helps reconcile these seemingly contradictory results as one particular ROS, H2O2, is known to both activate eNOS and upregulate its transcription.30,31,39 Consistent with this published data, we observed increased eNOS expression and activity in endothelial cells overexpressing Nox4 which was reduced in the presence of the H2O2 scavenger, catalase. In hypoxia, we found Nox4 upregulation that coincided with eNOS phosphorylation, whereas Nox4 RNAi limited the phosphorylation of eNOS. Collectively these data imply a physiologic role for Nox4 in mediating the endothelial response to hypoxia.

The data presented here also generally agree with a recent report40 demonstrating that Nox5, a calcium-dependent Nox isoform, enhances eNOS catalytic activity both in cultured endothelium and mouse aorta. Despite this increase in eNOS catalytic activity, Zhang and colleagues observed reduced NO• bioactivity suggesting extracellular consumption of NO•. One distinguishing feature of the present study is that Nox4 is thought to produce H2O2, an ROS species not associated with NO• consumption. Thus, our observations of enhanced NO• bioactivity with Nox4 may reflect the nature of the Nox product. Collectively, these two studies indicate that the phenotypic implications of ROS are contextual, and depend on the Nox isoform involved.

Nox4 is known to produce H2O214,15 and H2O2 is known to activate Akt41 and AMPK,42 two kinases important in eNOS regulation.43-45 Thus, our data is consistent with the idea that Nox4-derived H2O2 is responsible for promoting angiogenesis. With regards to the mechanism, we and others have demonstrated that Nox4 targeting to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) facilitates protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B) inhibition.24,25 In mice lacking PTP1B, Akt activation is prolonged.46 Since Nox4-mediated PTP1B inhibition enhances endothelial proliferation24 and PTP1B inhibition stimulates VEGF-induced endothelial proliferation and angiogenesis,47,48 it is plausible that PTP1B inhibition is a mechanism for Nox4-mediated eNOS activation.

Endothelial Nox4 is likely not the only ROS-sensitive component of angiogenesis. In fact, previous observations have demonstrated that Nox-stimulation of angiogenesis may involve other tissues such as the bone marrow 49 and other ROS producing sources such as Nox2.50 Although in our system we cannot rule out a role for the bone marrow-derived cells, our work in cultured cells coupled with observations of capillary sprouting in intact vessels indicate that the bone marrow is not necessary for our observations. With regard to Nox2, we find that manipulation of Nox4 expression does not affect Nox2 expression (Figure 2A)24 and therefore we conclude that the effect seen here is due specifically to Nox4 manipulation in the endothelium.

Collectively, the data presented here demonstrate that augmented endothelial Nox4 expression promotes angiogenesis and recovery from hypoxia through enhanced eNOS activation. Important questions remain such as the mechanism(s) whereby Nox4 is upregulated and the specific molecular targets between Nox4 and eNOS. Nevertheless, our findings support an adaptive role for Nox4 in the response to tissue injury.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Perspective

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are involved in promoting many vascular disease states such as hypertension, diabetes, and atherosclerosis and consequently have been the subject of considerable investigation. Identification of ROS sources has lead to the realization that “pathological” ROS are often produced by enzymes normally present in the vascular wall. These observations prompt the question: what is the physiologic role of ROS producing enzymes in the vasculature? To address this, we have investigated the role of NADPH oxidase 4 (Nox4), an ROS producing enzyme located in multiple vascular cells. We found that tissue hypoxia resulted in increased Nox4 expression, suggesting a role for this enzyme in the response to injury. Indeed, we observed that increased levels of Nox4 proved important for endothelial cell migration and proliferation, two features needed for endothelial-mediated angiogenesis. In addition, mice with excess endothelial Nox4 demonstrated accelerated blood flow recovery from limb ischemia, consistent with enhanced angiogenesis. This effect was due to the ability of Nox4 to activate endothelial nitric oxide synthase, another enzyme known to be involved in angiogenesis and injury responses. Our study lends insight into the important roles of ROS in cardiovascular cell biology and suggest Nox4 may be a potential therapeutic target for manipulating angiogenesis and tissue repair.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Yukio Shimisaki and Branch Craige for their technical assistance.

Funding Sources: This study was supported by NIH grants HL092122, HL098407, HL 081587 (to JFK) and F32HL099282 (to SMC) and core resources were supported by the Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center grant DK32520.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None

Contributor Information

Siobhan M. Craige, Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA.

Chen Kai, Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA.

Yongmei Pei, Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA.

Li Chunying, Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA.

Huang Xiaoyun, Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA.

Chen Christine, Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA.

Kaori Sato, Boston University School of Medicine, Whitaker Cardiovascular Institute, Boston, MA.

Kenneth Walsh, Boston University School of Medicine, Whitaker Cardiovascular Institute, Boston, MA.

John F. Keaney, Jr., Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA.

References

- 1.Vivekananthan DP, Penn MS, Sapp SK, Hsu A, Topol EJ. Use of antioxidant vitamins for the prevention of cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2003;361:2017–2023. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13637-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finkel T. Oxidant signals and oxidative stress. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:247–254. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(03)00002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ushio-Fukai M, Tang Y, Fukai T, Dikalov SI, Ma Y, Fujimoto M, Quinn MT, Pagano PJ, Johnson C, Alexander RW. Novel role of gp91(phox)-containing NAD(P)H oxidase in vascular endothelial growth factor-induced signaling and angiogenesis. Circ Res. 2002;91:1160–1167. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000046227.65158.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamaoka-Tojo M, Ushio-Fukai M, Hilenski L, Dikalov SI, Chen YE, Tojo T, Fukai T, Fujimoto M, Patrushev NA, Wang N, Kontos CD, Bloom GS, Alexander RW. IQGAP1, a novel vascular endothelial growth factor receptor binding protein, is involved in reactive oxygen species--dependent endothelial migration and proliferation. Circ Res. 2004;95:276–283. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000136522.58649.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harfouche R, Malak NA, Brandes RP, Karsan A, Irani K, Hussain SN. Roles of reactive oxygen species in angiopoietin-1/tie-2 receptor signaling. FASEB J. 2005;19:1728–1730. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3621fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maulik N, Das DK. Redox signaling in vascular angiogenesis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;33:1047–1060. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)01005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colavitti R, Pani G, Bedogni B, Anzevino R, Borrello S, Waltenberger J, Galeotti T. Reactive oxygen species as downstream mediators of angiogenic signaling by vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2/KDR. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:3101–3108. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107711200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yasuda M, Ohzeki Y, Shimizu S, Naito S, Ohtsuru A, Yamamoto T, Kuroiwa Y. Stimulation of in vitro angiogenesis by hydrogen peroxide and the relation with ETS-1 in endothelial cells. Life Sci. 1999;64:249–258. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(98)00560-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schroedl C, McClintock DS, Budinger GR, Chandel NS. Hypoxic but not anoxic stabilization of HIF-1alpha requires mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;283:L922–L931. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00014.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schumacker PT. Hypoxia, anoxia, and O2 sensing: the search continues. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;283:L918–L921. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00205.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bedard K, Krause KH. The NOX family of ROS-generating NADPH oxidases: physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:245–313. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00044.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dikalov SI, Dikalova AE, Bikineyeva AT, Schmidt HH, Harrison DG, Griendling KK. Distinct roles of Nox1 and Nox4 in basal and angiotensin II-stimulated superoxide and hydrogen peroxide production. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45:1340–1351. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Helmcke I, Heumuller S, Tikkanen R, Schroder K, Brandes RP. Identification of structural elements in Nox1 and Nox4 controlling localization and activity. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:1279–1287. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martyn KD, Frederick LM, von Loehneysen K, Dinauer MC, Knaus UG. Functional analysis of Nox4 reveals unique characteristics compared to other NADPH oxidases. Cell Signal. 2006;18:69–82. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Serrander L, Cartier L, Bedard K, Banfi B, Lardy B, Plastre O, Sienkiewicz A, Forro L, Schlegel W, Krause KH. NOX4 activity is determined by mRNA levels and reveals a unique pattern of ROS generation. Biochem J. 2007;406:105–114. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Szocs K, Lassegue B, Sorescu D, Hilenski LL, Valppu L, Couse TL, Wilcox JN, Quinn MT, Lambeth JD, Griendling KK. Upregulation of Nox-based NAD(P)H oxidases in restenosis after carotid injury. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:21–27. doi: 10.1161/hq0102.102189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suliman HB, Ali M, Piantadosi CA. Superoxide dismutase-3 promotes full expression of the EPO response to hypoxia. Blood. 2004;104:43–50. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vallet P, Charnay Y, Steger K, Ogier-Denis E, Kovari E, Herrmann F, Michel JP, Szanto I. Neuronal expression of the NADPH oxidase NOX4, and its regulation in mouse experimental brain ischemia. Neuroscience. 2005;132:233–238. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mittal M, Roth M, Konig P, Hofmann S, Dony E, Goyal P, Selbitz AC, Schermuly RT, Ghofrani HA, Kwapiszewska G, Kummer W, Klepetko W, Hoda MA, Fink L, Hanze J, Seeger W, Grimminger F, Schmidt HH, Weissmann N. Hypoxia-dependent regulation of nonphagocytic NADPH oxidase subunit NOX4 in the pulmonary vasculature. Circ Res. 2007;101:258–267. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.148015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhandarkar SS, Jaconi M, Fried LE, Bonner MY, Lefkove B, Govindarajan B, Perry BN, Parhar R, Mackelfresh J, Sohn A, Stouffs M, Knaus U, Yancopoulos G, Reiss Y, Benest AV, Augustin HG, Arbiser JL. Fulvene-5 potently inhibits NADPH oxidase 4 and blocks the growth of endothelial tumors in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:2359–2365. doi: 10.1172/JCI33877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ago T, Kitazono T, Ooboshi H, Iyama T, Han YH, Takada J, Wakisaka M, Ibayashi S, Utsumi H, Iida M. Nox4 as the major catalytic component of an endothelial NAD(P)H oxidase. Circulation. 2004;109:227–233. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000105680.92873.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Buul JD, Fernandez-Borja M, Anthony EC, Hordijk PL. Expression and localization of NOX2 and NOX4 in primary human endothelial cells. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2005;7:308–317. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu T, Ramachandrarao SP, Siva S, Valancius C, Zhu Y, Mahadev K, Toh I, Goldstein BJ, Woolkalis M, Sharma K. Reactive oxygen species production via NADPH oxidase mediates TGF-beta-induced cytoskeletal alterations in endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;289:F816–F825. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00024.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen K, Kirber MT, Xiao H, Yang Y, Keaney JF., Jr Regulation of ROS signal transduction by NADPH oxidase 4 localization. J Cell Biol. 2008;181:1129–1139. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200709049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mahadev K, Motoshima H, Wu X, Ruddy JM, Arnold RS, Cheng G, Lambeth JD, Goldstein BJ. The NAD(P)H oxidase homolog Nox4 modulates insulin-stimulated generation of H2O2 and plays an integral role in insulin signal transduction. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:1844–1854. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.5.1844-1854.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang J, Jones SP, Suhara T, Greer JJ, Ware PD, Nguyen NP, Perlman H, Nelson DP, Lefer DJ, Walsh K. Endothelial cell overexpression of fas ligand attenuates ischemia-reperfusion injury in the heart. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:15185–15191. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211707200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murohara T, Asahara T, Silver M, Bauters C, Masuda H, Kalka C, Kearney M, Chen D, Symes JF, Fishman MC, Huang PL, Isner JM. Nitric oxide synthase modulates angiogenesis in response to tissue ischemia. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:2567–2578. doi: 10.1172/JCI1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Couffinhal T, Silver M, Zheng LP, Kearney M, Witzenbichler B, Isner JM. Mouse model of angiogenesis. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:1667–1679. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee PC, Salyapongse AN, Bragdon GA, Shears LL, Watkins SC, Edington HD, Billiar TR. Impaired wound healing and angiogenesis in eNOS-deficient mice. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:H1600–H1608. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.4.H1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Drummond GR, Cai H, Davis ME, Ramasamy S, Harrison DG. Transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression by hydrogen peroxide. Circ Res. 2000;86:347–354. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.3.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thomas SR, Chen K, Keaney JF., Jr Hydrogen peroxide activates endothelial nitric-oxide synthase through coordinated phosphorylation and dephosphorylation via a phosphoinositide 3-kinase-dependent signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:6017–6024. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109107200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gerald D, Berra E, Frapart YM, Chan DA, Giaccia AJ, Mansuy D, Pouyssegur J, Yaniv M, Mechta-Grigoriou F. JunD reduces tumor angiogenesis by protecting cells from oxidative stress. Cell. 2004;118:781–794. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xia C, Meng Q, Liu LZ, Rojanasakul Y, Wang XR, Jiang BH. Reactive oxygen species regulate angiogenesis and tumor growth through vascular endothelial growth factor. Cancer Res. 2007;67:10823–10830. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen K, Craige SE, Keaney JF., Jr Downstream targets and intracellular compartmentalization in Nox signaling. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:2467–2480. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murohara T, Asahara T. Nitric oxide and angiogenesis in cardiovascular disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2002;4:825–831. doi: 10.1089/152308602760598981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jozkowicz A, Pankiewicz J, Dulak J, Partyka L, Wybranska I, Huk I, Dembinska-Kiec A. Nitric oxide mediates the mitogenic effects of insulin and vascular endothelial growth factor but not of leptin in endothelial cells. Acta Biochim Pol. 1999;46:703–715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ziche M, Parenti A, Ledda F, Dell'Era P, Granger HJ, Maggi CA, Presta M. Nitric oxide promotes proliferation and plasminogen activator production by coronary venular endothelium through endogenous bFGF. Circ Res. 1997;80:845–852. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.6.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Price DT, Vita JA, Keaney JF., Jr Redox control of vascular nitric oxide bioavailability. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2000;2:919–935. doi: 10.1089/ars.2000.2.4-919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cai H, Li Z, Davis ME, Kanner W, Harrison DG, Dudley SC., Jr Akt-dependent phosphorylation of serine 1179 and mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 cooperatively mediate activation of the endothelial nitric-oxide synthase by hydrogen peroxide. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63:325–331. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.2.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang Q, Malik P, Pandey D, Gupta S, Jagnandan D, Belin de CE, Banfi B, Marrero MB, Rudic RD, Stepp DW, Fulton DJ. Paradoxical activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by NADPH oxidase. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:1627–1633. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.168278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martindale JL, Holbrook NJ. Cellular response to oxidative stress: signaling for suicide and survival. J Cell Physiol. 2002;192:1–15. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Emerling BM, Weinberg F, Snyder C, Burgess Z, Mutlu GM, Viollet B, Budinger GR, Chandel NS. Hypoxic activation of AMPK is dependent on mitochondrial ROS but independent of an increase in AMP/ATP ratio. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46:1386–1391. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen ZP, Mitchelhill KI, Michell BJ, Stapleton D, Rodriguez-Crespo I, Witters LA, Power DA, Ortiz de Montellano PR, Kemp BE. AMP-activated protein kinase phosphorylation of endothelial NO synthase. FEBS Lett. 1999;443:285–289. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01705-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dimmeler S, Fleming I, Fisslthaler B, Hermann C, Busse R, Zeiher AM. Activation of nitric oxide synthase in endothelial cells by Akt-dependent phosphorylation. Nature. 1999;399:601–605. doi: 10.1038/21224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fulton D, Gratton JP, McCabe TJ, Fontana J, Fujio Y, Walsh K, Franke TF, Papapetropoulos A, Sessa WC. Regulation of endothelium-derived nitric oxide production by the protein kinase Akt. Nature. 1999;399:597–601. doi: 10.1038/21218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Galic S, Hauser C, Kahn BB, Haj FG, Neel BG, Tonks NK, Tiganis T. Coordinated regulation of insulin signaling by the protein tyrosine phosphatases PTP1B and TCPTP. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:819–829. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.2.819-829.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nakamura Y, Patrushev N, Inomata H, Mehta D, Urao N, Kim HW, Razvi M, Kini V, Mahadev K, Goldstein BJ, McKinney R, Fukai T, Ushio-Fukai M. Role of protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B in vascular endothelial growth factor signaling and cell-cell adhesions in endothelial cells. Circ Res. 2008;102:1182–1191. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.167080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Soeda S, Shimada T, Koyanagi S, Yokomatsu T, Murano T, Shibuya S, Shimeno H. An attempt to promote neo-vascularization by employing a newly synthesized inhibitor of protein tyrosine phosphatase. FEBS Lett. 2002;524:54–58. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Urao N, Inomata H, Razvi M, Kim HW, Wary K, McKinney R, Fukai T, Ushio-Fukai M. Role of nox2-based NADPH oxidase in bone marrow and progenitor cell function involved in neovascularization induced by hindlimb ischemia. Circ Res. 2008;103:212–220. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.176230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ikeda S, Yamaoka-Tojo M, Hilenski L, Patrushev NA, Anwar GM, Quinn MT, Ushio-Fukai M. IQGAP1 regulates reactive oxygen species-dependent endothelial cell migration through interacting with Nox2. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:2295–2300. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000187472.55437.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.