Summary

Background This trial evaluated the safety, tolerability and maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of afatinib, a novel ErbB Family Blocker. Methods In this open-label, dose-escalation Phase I study, afatinib was administered continuously, orally, once-daily for 28 days to patients with advanced or metastatic solid tumors. Dose escalation was performed in a 3 + 3 design, with a starting dose of 10 mg/day (d); doses were doubled for each successive cohort until the MTD was defined. The MTD cohort was expanded to a total of 19 patients. Incidence and severity of adverse events (AEs), antitumor activity and pharmacokinetics were assessed. Results Thirty patients received at least one dose of afatinib. Twenty-nine patients were evaluable for response. Dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs) consisting of Grade 3 diarrhea were observed in two out of three patients treated at 60 mg/d. The MTD was determined at 40 mg/d. The most frequent treatment-related AEs were diarrhea and mucosal inflammation reported in 76.7 % and 43.3 % of patients respectively. Five patients had stable disease with a median progression-free survival of 111 days. No objective responses occurred. Pharmacokinetic data showed no deviation from dose-proportionality and steady-state was reached on Day 8 at the latest. Conclusions Afatinib was well tolerated with manageable side effects when administered once-daily, continuously at a dose of 40 mg.

Keywords: Afatinib, Phase I, ErbB Family Blocker, Dose escalation, Irreversible tyrosine kinase inhibitor

Background

The ErbB Family of receptor tyrosine kinases bind various extracellular growth factors and play a crucial role in regulating cell growth and proliferation [1, 2]. The four members of the ErbB Receptor Family are the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR, ErbB1), HER2 (ErbB2), HER3 (ErbB3) and HER4 (ErbB4) and comprise an extracellular ligand-binding domain (except for HER2), a single membrane-spanning domain and, on the cytoplasmic side of the cell membrane, a tyrosine kinase active site (except for HER3) [3]. Binding of extracellular growth factor ligands to the ErbB Receptor Family causes a structural change in the receptor which facilitates dimerization of the receptors, which can form homo- or heterodimers. This stimulates their tyrosine kinase activity, initiating intracellular signaling cascades [2, 4]. HER2 has no associated ligand, but functions as a co-receptor with the other members of the ErbB Family – it is the preferred dimerization partner for the other receptors [3, 4].

Dysregulated signaling via members of the ErbB Receptor Family plays a role in different tumor types [3, 5–7]. As a result of this observation, a number of compounds have been developed which inhibit signaling via the ErbB Receptor Family tyrosine kinases. The currently available small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors, gefitinib and erlotinib, target EGFR and have improved clinical outcomes in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [8–12]. Similarly, the humanized monoclonal antibody, trastuzumab, directed against the extracellular domain of the HER2 receptor, is indicated for the treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer in the adjuvant and metastatic setting, as well as the small molecule dual EGFR and HER2 tyrosine kinase inhibitor lapatinib in combination with capecitabine, which has clinical efficacy in metastatic breast cancer [13, 14]. The success of these agents validates the ErbB Receptor Family as a target for cancer therapy.

Further developments in understanding how the currently available reversible tyrosine kinase inhibitors mediated their effects on the ErbB Receptor Family led to the design of afatinib (BIBW 2992), an oral irreversible ErbB Family Blocker with half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values of 0.5 nM, 14 nM, 1 nM and 10 nM for EGFR, HER2, HER4, and EGFR L858R/T790M, respectively [15, 16]. Afatinib irreversibly blocks ErbB Receptor Family tyrosine kinase activity and, in doing so, is thought to inhibit all cancer-relevant ErbB Family dimers. In preclinical models, this prevents tumor growth and can also initiate tumor regression [16]. So far, afatinib has demonstrated substantial, sustained activity in vitro and broad spectrum activity in vivo xenograft models [16–18].

Several Phase I studies have investigated the safety and antitumor activity of afatinib monotherapy when administered either as a 2-week on/off schedule [15], a 3-week on/1-week off schedule [19, 20] or as continuous dosing [21]. The recommended Phase II dose (RP2D) of afatinib was reported as 70 mg once-daily in the 2-week on/off study and shown to be well tolerated. For the 3-week on/1-week off schedule study, the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) was established at 55 mg/d; however, due to excess dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs) in the MTD expansion cohort it was not considered as a RP2D. Continuous afatinib dosing was explored in two separate Phase I studies. One of these studies has already been reported [21] and established a RP2D at 50 mg once-daily continuous. Results from the other study investigating a continuous schedule are reported here.

The primary objective of this study was to determine the safety and tolerability, and to establish the MTD of oral, once-daily afatinib when administered continuously in 28-day cycles. Secondary objectives were to assess the antitumor activity of afatinib, as well as its pharmacokinetic profile at steady state.

Methods

Study design

This was a Phase I, two-center, open-label study designed to establish the MTD and assess the overall safety and antitumor activity of afatinib in patients with advanced solid tumors. Patients received a single daily oral dose of afatinib for 28 days continuously. If treatment was tolerated, patients were allowed to receive repeated 28-day treatment cycles until the occurrence of progressive disease or toxicity. The afatinib starting dose for the first cohort was 10 mg/d, and the dose was doubled for each successive cohort until one or more patients experienced a DLT. Thereafter, dose escalation was to be of no more than 50 % increments.

The trial was conducted in a 3 + 3 design. Three patients were treated at each dose level. If one of them experienced a DLT, three additional patients were treated at that dose level. The MTD was the highest dose at which no more than one of six patients experienced a DLT. If two or more patients experienced a DLT, a total of six patients were treated at one dose tier below. Once the MTD was established, subject enrolment at the MTD was expanded to include a minimum of 18 patients to better characterize the safety profile, antitumor activity and the pharmacokinetic properties. Patients who experienced a DLT stopped study medication but could restart at a lower dose level if they recovered to Grade ≤1 adverse event (AE) within 2 weeks.

The following drug-related AEs (National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events; NCI CTCAE version 3.0) [22] qualified as DLTs: Grade 4 hematologic toxicity, Grade 3 or 4 non-hematologic toxicity (except untreated nausea, untreated vomiting, or untreated diarrhea); Grade 2 or higher worsening of cardiac left ventricular function; Grade 2 or higher worsening of renal function as measured by serum creatinine, newly developed proteinuria, or newly developed decrease in glomerular filtration rate; Grade ≥3 diarrhea despite loperamide or other anti-diarrheal medication; persistent Grade ≥2 diarrhea for 7 or more days despite supportive care; Grade ≥3 nausea and/or vomiting despite antiemetic treatment; persistent Grade ≥2 nausea and/or vomiting for 7 or more days despite supportive care.

Patients underwent response assessment as defined in the Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.0 following completion of two 28-day cycles of therapy. Patients with stable disease or objective response who were tolerating study drug were eligible for continued therapy with repeat response assessments every other cycle.

Study population

Male or female patients with a pathologically confirmed solid tumor, historically known to express EGFR and/or HER2, for whom no proven therapy existed or who were not amenable to established treatments, were eligible. Other eligibility criteria included: informed consent; age ≥18 years; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (EGOG) performance status of 0–2; life expectancy of at least 3 months; recovery from any prior surgery and any AEs related to previous therapy, and no prior treatment with an EGFR- or HER2-inhibiting drug within 4 weeks (8 weeks for trastuzumab) before the start of study medication.

An additional 12 patients recruited at the MTD were also required to have measurable disease according to RECIST version 1.0 [23] or evaluable disease using recognized tumor markers, such as prostate-specific antigen for prostate cancer or cancer antigen 125 for ovarian cancer.

Concomitant medications

Concomitant medications were given as clinically required. Recommendations for treatment of diarrhea, nausea, vomiting and rash were provided in the protocol. Additional chemo-, immuno-, hormone- or radiotherapy was not permitted, with the exception of ongoing hormone treatment for prostate cancer, bisphosphonates, or palliative radiotherapy.

Outcome measures

Safety was assessed by monitoring the incidence and severity of AEs, which were graded according to the NCI CTCAE criteria version 3.0. Antitumor activity was assessed by tumor measurements according to RECIST and performed at 8-week intervals.

Pharmacokinetic analysis

Plasma concentrations of afatinib were determined at distinct time points on Day 1: pre-dose, 3 h and 24 h after the first drug administration. Pharmacokinetic (PK) parameters of afatinib were determined on Days 27–28 (steady state) of continuous treatment at the following timepoints: before drug administration and 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 9 and 24 h after drug administration. Trough levels were determined on Days 8, 15 and 22 in the first treatment cycle and on Days 15 and 28 during repeated treatment periods up to the sixth cycle of therapy.

Noncompartmental analysis was conducted using WinNonlin® (version 4.1, Pharsight, Mountainview, CA). Standard noncompartmental methods were used to calculate the area under the plasma concentration-time curve over the time interval from 0 to 24 h at steady state (AUC0–24,ss), maximum measured concentration of the analyte in plasma at steady state (Cmax,ss), apparent clearance of the analyte in plasma following extravascular administration (CL/Fss), apparent volume of distribution during the terminal phase following an extravascular dose (Vz/Fss) and terminal half-life of the analyte in plasma at steady state (t1/2,ss). Time from dosing to the maximum concentration of the analyte in plasma at steady state (tmax,ss) was reported as a median value.

Results

Patient demographics and disposition

A total of 30 patients received at least one dose of afatinib and were included in the safety analysis. The baseline demographic characteristics of these patients are provided in Table 1. Patients had different cancer types (the most common being ovarian and NSCLC) and were heavily pre-treated (96.7 % had ≥ 3 prior anticancer therapies). Patient disposition and exposure are listed in Table 2. The MTD cohort included six patients to establish the MTD and an additional 13 patient expansion cohort instead of the planned 12, as two patients were entered very close together in time. This gave a total of 19 patients treated at MTD.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and disease characteristics

| Total | |

|---|---|

| Number of patients treated, n (%) | 30 (100) |

| Age (years) | |

| Median (range) | 60.0 (35–80) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 18 (60) |

| Female | 12 (40) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 25 (83.3) |

| Black | 4 (13.3) |

| Asian | 1 (3.3) |

| Smoking status, n (%) | |

| Never-smoker | 10 (33.3) |

| Ex-smoker | 19 (63.3) |

| Smoker | 1 (3.3) |

| ECOG PS at screening, n (%) | |

| 0 | 13 (43.3) |

| 1 | 12 (40.0) |

| 2 | 5 (16.7) |

| Cancer type, n (%) | |

| Ovarian | 6 (20.0) |

| NSCLC | 4 (13.3) |

| Prostate | 3 (10.0) |

| Renal | 3 (10.0) |

| Breast | 3 (10.0) |

| Colorectal | 2 (6.7) |

| Pancreatic | 2 (6.7) |

| Other | 7 (23.3) |

| Number of prior therapies, n (%) | |

| 2 | 1 (3.3) |

| ≥3 | 29 (96.7) |

| Number of prior chemotherapy regimens, n (%) | |

| 0 | 1 (3.3) |

| 1–2 | 4–9 (30.0) |

| ≥3 | 20 (66.7) |

| Prior radiotherapy, n (%) | 18 (60.0) |

ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer

Table 2.

Patient disposition

| Afatinib dose (mg/day) | 10 | 20 | 40 | 60 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients treated (n) | 5 | 3 | 19 | 3 | 30 |

| Patients with DLT events during the initial 28-day treatment period (n) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2a | 3 |

| Patients discontinued owing to (n, %): | |||||

| DLT | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.3) | 1 (33.3) | 2 (6.7) |

| Other AEs | 0 | 0 | 2 (10.5) | 1 (33.3) | 3 (10.0) |

| Disease progression | 4 (80) | 3 (100) | 14 (73.7) | 1 (33.3) | 22 (73.3) |

| Other | 1 (20) | 0 | 2 (10.5) | 0 | 3 (10.0) |

aOne patient continued on afatinib treatment after dose reduction to 40 mg/day

DLT, dose-limiting toxicity; AE, adverse event; Other, worsening of disease under study, lost to follow-up, non-compliance and other

Assessment of DLT and MTD

In total, three patients developed DLT during the first 28-day treatment cycle in the dose escalation phase, two out of three patients in the 60 mg cohort and one patient in the 40 mg cohort. Of the two DLTs that occurred in the 60 mg cohort, one patient was 80 years old, with prostate cancer, and the second patient was 77 years old, with endometrial cancer. In both cases, Grade 3 diarrhea occurred despite an optimal anti-diarrheal treatment. One of these patients (an 80 year-old with prostate cancer) continued on treatment after dose reduction to 40 mg/d. With two of three DLTs observed in the afatinib 60 mg cohort and no DLT observed with the afatinib 40 mg dose in the initial cohort of three patients, the 40 mg dose was further assessed in six patients, and with one DLT (Grade 3 diarrhea occurred in a 66 year-old patient with ovarian cancer), it was established as the MTD. The cohort was then expanded by a further 13 patients without additional DLTs occurring. As no intermediate dose between 40 mg and 60 mg afatinib was planned in the study, the MTD and RP2D for afatinib was defined at 40 mg/day when administered once-daily in a 28-day continuous-dosing treatment schedule.

Safety and tolerability assessments

All 30 patients included in the safety analysis experienced at least one AE – 29 had AEs considered by the investigators to be related to study medication. The most frequently reported treatment-related AEs are summarized by dose group and treatment cycle (cycle 1 versus cycle ≥2) and CTCAE Grade in Table 3. Across all dose groups and treatment courses, diarrhea was the most commonly reported treatment-related AE (76.7 %), followed by mucosal inflammation (43.3 %), rash and nausea (both 36.7 %), fatigue and dermatitis acneiform (both 33.3 %). Diarrhea occurred across all dose ranges, but CTCAE Grade 3 events occurred only in the 40 mg/d and 60 mg/d groups. The onset of diarrhea typically occurred during the first treatment course in 70 % of patients. However, 76.7 % of the patients reported diarrhea during all courses.

Table 3.

Selected treatment-related adverse events by treatment dose, highest CTCAE Grade and preferred term

| Afatinib dose (mg/day) | 10 | 20 | 40 | 60 | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gradea | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||||||||||

| Courseb | 1 | ≥2 | 1 | ≥2 | 1 | ≥2 | 1 | ≥2 | 1 | ≥2 | 1 | ≥2 | 1 | ≥2 | 1 | ≥2 | 1 | ≥2 | 1 | ≥2 | 1 | ≥2 | 1 | ≥2 |

| Decreased appetite | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Nausea | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Stomatitis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fatigue | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Rash | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dry skin | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dermatitis acneiform | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Rash erythematous | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mucosal inflammation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Epistaxis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

aWorst CTCAE Grade; bcourse in which AE started; cycle length: 28 days; no treatment-related Grade 3 AEs were observed in the 10 mg dose cohort

CTCAE, Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events; AE, adverse event

Six deaths were reported; one occurred during the treatment period and five other deaths were reported in the post-treatment period. None were considered to be related to the study medication.

No relevant changes in laboratory evaluations, i.e. those determined to be CTCAE Grade ≥2, were related to study medication. No cardiac events were reported throughout the treatment period.

Antitumor activity

Twenty-nine out of 30 patients who had evaluable disease as per RECIST were included in the tumor response analysis. No objective responses were observed during the course of this study. Three patients remained on treatment for more than 16 weeks: one in the 20 mg/d group and two in the 40 mg/d group. Two of these had stable disease beyond six treatment courses (24 weeks) – one ovarian cancer patient in the 20 mg group (204 days) and one patient with thymic carcinoma in the 40 mg group (280 days). In the 40 mg dose cohort, five patients (three with ovarian cancer, one with thyroid cancer and one with prostate cancer) experienced stable disease with a median progression-free survival of 111 days (range: 49–204 days).

Pharmacokinetics

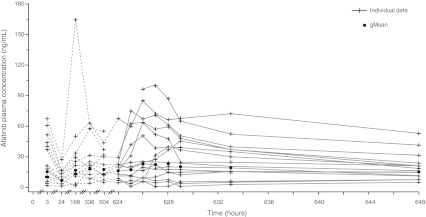

Individual and geometric mean (gMean) drug plasma concentration–time profiles of afatinib (40 mg dose group) during Treatment Period 1 are shown in Fig. 1. Steady-state was reached on Day 8 of Treatment Period 1 at the latest. Moderate-to-high inter-individual variability of the plasma concentrations of the patients in the 40 mg dose group was detected.

Fig. 1.

Individual and gMean drug plasma concentration–time profiles of afatinib after oral administration of 40 mg/day for 27 days (n = 17). gMean, geometric mean

Across all dose groups, median tmax values at steady state ranged from 3 to 5 h after oral administration of afatinib. In general, at steady-state, gMean Cmax values and total exposure increased with increasing doses of afatinib (Table 4) and there was no obvious deviation from dose-proportionality. It should be noted that the gMean pharmacokinetic parameters of the 20 mg dose group (n = 3) were mainly influenced by one single patient, who displayed much higher afatinib plasma concentrations compared with the rest of the 20 mg dose group. As a result, values of the 20 mg dose group were therefore in a similar range to the pharmacokinetic parameters of the 40 mg dose group. The gMean terminal half-life following oral dosing ranged from 34 to 48 h; the overall gMean was 37.4 h (data not shown). Total body clearance was determined with gMean values between 567 mL/min and 2,980 mL/min and an overall gMean of 1,330 mL/min across all groups (data not shown). Afatinib exhibited a high apparent volume of distribution during the terminal phase, with gMean values between 1,990 and 16,100 liters (overall gMean: 3,630 liters – data not shown). However, values obtained for total body clearance and volume of distribution should be treated with caution, as the absolute bioavailability of afatinib in humans is unknown.

Table 4.

Geometric mean (and gCV%) pharmacokinetic parameters of afatinib on Days 27–28 (steady state) after multiple oral administration of afatinib once-daily

| Day 27 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afatinib dose q.d. (No. of patients) | 10 mg (n = 3) | 20 mg (n = 3) | 40 mg (n = 17) | 60 mg (n = 1)|| | |||||

| gMean | gCV [%] | gMean | gCV [%] | gMean | gCV [%] | gMean | gCV [%] | ||

| Cmax,ss | [ng/mL] | 3.18 | 63.7 | 24.6 | 158 | 29.0 | 105 | 86.7 | – |

| Cpre,ss | [ng/mL] | 2.64b | 54.4 | 12.5 | 243 | 16.1c | 66.9 | 52.3 | – |

| tmax,ssa | [h] | 3.00 | 1.00–3.95 | 5.00 | 4.98–5.08 | 2.95 | 1.22–23.8 | 2.98 | – |

| AUC0–24,ss | [ng·h/mL] | 55.9 | 54.2 | 442 | 173 | 498c | 90.3 | 1760 | – |

| t1/2,ss | [h] | 47.0b | 0.0356 | 48.4 | 88.9 | 34.0d | 64.6 | 40.5 | – |

| Vz/F,ss | [L] | 16100b | 19.4 | 3160 | 273 | 3150d | 106 | 1990 | – |

| CL/F,ss | [mL/min] | 2980 | 54.2 | 755 | 173 | 1340c | 90.3 | 567 | – |

aMedian and range; bN = 2; cN = 16; dN = 14; ||No descriptive statistics, only individual values from one patient

AUC0–24,ss, area under the plasma concentration versus time curve from 0 to 24 h at steady state; Cmax,ss, peak plasma concentration at steady state; Cpre,ss, pre-dose plasma concentrations at steady state; CL/F,ss, apparent clearance of the analyte in plasma following extravascular administration at steady state; gCV [%], geometric coefficient of variation; gMean, geometric mean; t1/2,ss, terminal half-life at steady state; tmax,ss, time to peak plasma concentration at steady state; Vz/F,ss, apparent volume of distribution of the analyte in plasma following extravascular administration at steady state

Discussion

A number of small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors have been developed, which target the receptors of the ErbB Family, including gefitinib, erlotinib and lapatinib. These compounds have shown efficacy in the treatment of various solid tumors, including NSCLC [8–12] and metastatic breast cancer [13, 14]. Despite the improvements achieved in patient outcomes with reversible inhibitors of EGFR or EGFR and HER2, primary and acquired resistance to these agents remains a clinical challenge. This is exemplified by the emergence of resistance mechanisms such as the T790M EGFR mutation in NSCLC [24]. It is likely that patients will benefit from treatment with an irreversible ErbB Family Blocker, such as afatinib that showed activity against EGFR-mutated NSCLC as well as in trastuzumab resistant HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer [25].

This Phase I dose-escalation study was performed to determine the safety and tolerability, and to establish the MTD for continuous administration of afatinib, an ErbB Family Blocker. Results from this trial show that afatinib administered continuously for 28 days at the MTD of 40 mg/d is well tolerated with a manageable safety profile. Dose escalation to a dose between 40 mg/d and 60 mg/d, which clearly was above the MTD within this trial was not foreseen. Afatinib displayed good pharmacologic properties and pharmacokinetic results are in line with other data from Phase I studies of continuous or intermittent dosing of afatinib [15, 21, 26]. All pharmacokinetic parameters displayed moderate-to-high variability within the expected range for orally administered EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors [27, 28].

In general, the AEs that were associated with afatinib in this study and the overall safety profile of afatinib are consistent with those observed with EGFR inhibitors [29–32]. Only three patients experienced a DLT consisting of Grade 3 diarrhea (two at 60 mg, one at 40 mg). Gastrointestinal and skin-related AEs were reported most frequently, and usually occurred within the first 2 weeks of treatment. These AEs were manageable with dose reduction and appropriate supportive care allowing prolonged administration of afatinib as with the currently available EGFR inhibitors erlotinib and gefitinib [31, 33, 34].

Although, no objective response was observed in this trial, several heavily pre-treated patients experienced stable disease. It is of note that patients were not preselected based on the overexpression of EGFR or HER2.

Initial data from other Phase I dose-escalation studies in patients with advanced solid tumors showed that afatinib could be safely administered at a dose of 70 mg/d in a 2-week on/2-week off schedule [35]. Afatinib was administered with tolerable side effects at 40 mg/d in a 3-week on/1-week off schedule [36]. Results from this trial indicate that a dose of 60 mg/d is too high for a continuous dosing regimen, and that a dose of 40 mg/d can be safely administered, while data from another Phase I trial have established a RP2D at 50 mg/d [21]. This dose was subsequently assessed in Phase II and III trials and its efficacy and tolerability was confirmed in a variety of tumor types [37, 38].

In conclusion, in this trial we confirmed the good tolerability with manageable safety profile of afatinib when administered orally, at a dose of 40 mg once-daily continuously.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Boehringer Ingelheim. Editorial support for the preparation of this manuscript was provided by Jamie Singer of Ogilvy Healthworld Medical Education; funding was provided by Boehringer Ingelheim.

Author financial disclosures

No financial disclosures related to this manuscript reported.

Ethical standards

This study was carried out according to the Declaration of Helsinki and the Good Clinical Practice (GCP) and International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) guidelines, and was approved by the local Institutional Review Boards of the participating institutions. The study was conducted between November 2004 and September 2006.

Footnotes

Trial registration

NA, first patient in 16 Nov 2004

Contributor Information

Michael S. Gordon, Phone: +1-480-8605000, FAX: +1-480-3140033, Email: mgordon@azpoh.com

David S. Mendelson, Email: dmendelson@azpoh.com

Mitchell Gross, Email: mitchell.gross@usc.edu.

Martina Uttenreuther-Fischer, Email: martina.uttenreuther-fischer@boehringer-ingelheim.com.

Mahmoud Ould-Kaci, Email: mahmoud.ould-kaci@boehringer-ingelheim.com.

Yihua Zhao, Email: mary.zhao@boehringer-ingelheim.com.

Peter Stopfer, Email: peter.stopfer@boehringer-ingelheim.com.

David B. Agus, Email: agus@USC.edu

References

- 1.Ciardiello F, Tortora G. EGFR antagonists in cancer treatment. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(11):1160–1174. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0707704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yarden Y, Sliwkowski MX. Untangling the ErbB signalling network. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2(2):127–137. doi: 10.1038/35052073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Normanno N, Bianco C, Strizzi L, Mancino M, Maiello MR, De Luca A, Caponigro F, Salomon DS. The ErbB receptors and their ligands in cancer: an overview. Curr Drug Targets. 2005;6(3):243–257. doi: 10.2174/1389450053765879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holbro T, Beerli RR, Maurer F, Koziczak M, Barbas CF, 3rd, Hynes NE. The ErbB2/ErbB3 heterodimer functions as an oncogenic unit: ErbB2 requires ErbB3 to drive breast tumor cell proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(15):8933–8938. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1537685100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arteaga CL. Epidermal growth factor receptor dependence in human tumors: more than just expression? Oncologist. 2002;7(Suppl 4):31–39. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.7-suppl_4-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iivanainen E, Elenius K. ErbB targeted drugs and angiogenesis. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2010;8(3):421–431. doi: 10.2174/157016110791112241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baselga J. Why the epidermal growth factor receptor? The rationale for cancer therapy. Oncologist. 2002;7(Suppl 4):2–8. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.7-suppl_4-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shepherd FA, Rodrigues Pereira J, Ciuleanu T, Tan EH, Hirsh V, Thongprasert S, Campos D, Maoleekoonpiroj S, Smylie M, Martins R, van Kooten M, Dediu M, Findlay B, Tu D, Johnston D, Bezjak A, Clark G, Santabarbara P, Seymour L. Erlotinib in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(2):123–132. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, Yang CH, Chu DT, Saijo N, Sunpaweravong P, Han B, Margono B, Ichinose Y, Nishiwaki Y, Ohe Y, Yang JJ, Chewaskulyong B, Jiang H, Duffield EL, Watkins CL, Armour AA, Fukuoka M. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(10):947–957. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maemondo M, Inoue A, Kobayashi K, Sugawara S, Oizumi S, Isobe H, Gemma A, Harada M, Yoshizawa H, Kinoshita I, Fujita Y, Okinaga S, Hirano H, Yoshimori K, Harada T, Ogura T, Ando M, Miyazawa H, Tanaka T, Saijo Y, Hagiwara K, Morita S, Nukiwa T. Gefitinib or Chemotherapy for Non–Small- Cell Lung Cancer with Mutated EGFR. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2380–2388. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosell R, Moran T, Queralt C, Porta R, Cardenal F, Camps C, Majem M, Lopez-Vivanco G, Isla D, Provencio M, Insa A, Massuti B, Gonzalez-Larriba JL, Paz-Ares L, Bover I, Garcia-Campelo R, Moreno MA, Catot S, Rolfo C, Reguart N, Palmero R, Sanchez JM, Bastus R, Mayo C, Bertran-Alamillo J, Molina MA, Sanchez JJ, Taron M. Screening for epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(10):958–967. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitsudomi T, Morita S, Yatabe Y, Negoro S, Okamoto I, Tsurutani J, Seto T, Satouchi M, Tada H, Hirashima T, Asami K, Katakami N, Takada M, Yoshioka H, Shibata K, Kudoh S, Shimizu E, Saito H, Toyooka S, Nakagawa K, Fukuoka M. Gefitinib versus cisplatin plus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor (WJTOG3405): an open label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(2):121–128. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70364-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cameron D, Casey M, Press M, Lindquist D, Pienkowski T, Romieu CG, Chan S, Jagiello-Gruszfeld A, Kaufman B, Crown J, Chan A, Campone M, Viens P, Davidson N, Gorbounova V, Raats JI, Skarlos D, Newstat B, Roychowdhury D, Paoletti P, Oliva C, Rubin S, Stein S, Geyer CE. A phase III randomized comparison of lapatinib plus capecitabine versus capecitabine alone in women with advanced breast cancer that has progressed on trastuzumab: updated efficacy and biomarker analyses. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;112(3):533–543. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9885-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geyer CE, Forster J, Lindquist D, Chan S, Romieu CG, Pienkowski T, Jagiello-Gruszfeld A, Crown J, Chan A, Kaufman B, Skarlos D, Campone M, Davidson N, Berger M, Oliva C, Rubin SD, Stein S, Cameron D. Lapatinib plus capecitabine for HER2-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(26):2733–2743. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa064320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eskens FA, Mom CH, Planting AS, Gietema JA, Amelsberg A, Huisman H, van Doorn L, Burger H, Stopfer P, Verweij J, de Vries EG. A phase I dose escalation study of BIBW 2992, an irreversible dual inhibitor of epidermal growth factor receptor 1 (EGFR) and 2 (HER2) tyrosine kinase in a 2-week on, 2-week off schedule in patients with advanced solid tumours. Br J Cancer. 2008;98(1):80–85. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li D, Ambrogio L, Shimamura T, Kubo S, Takahashi M, Chirieac LR, Padera RF, Shapiro GI, Baum A, Himmelsbach F, Rettig WJ, Meyerson M, Solca F, Greulich H, Wong KK. BIBW2992, an irreversible EGFR/HER2 inhibitor highly effective in preclinical lung cancer models. Oncogene. 2008;27(34):4702–4711. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shimamura T, Gewulich H, Solca F, Wong K. Efficacy of BIBW 2992, a potent irreversible inhibitor of EGFR and HER2 in human NSCLC xenografts and in a transgenic mouse lung-cancer model. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2(8):S380. doi: 10.1097/01.JTO.0000283232.53465.68. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Solca F, Baum A, Guth B, Colbatzky F, Blech S, Amelsberg A, Himmelsbach F (2005) BIBW 2992, an irreversible dual EGFR/HER2 receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor for cancer therapy. Proceedings, AACR-NCI-EORTC International Conference on Molecular Targets and Cancer Therapeutics Philadelphia, PA 14–18 November 2005:118 (Abstract A244)

- 19.Marshall J, Lewis N, Amelsberg A, Briscoe J, Hwang J, Malik S, Cohen R (2005) A Phase I dose escalation study of BIBW 2992, an irreversible dual EGFR/HER2 receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in a 3 week on 1 week off schedule in patients with advanced solid tumors. Proceedings, AACR-NCI-EORTC International Conference on Molecular Targets and Cancer Therapeutics:168(Abstract B161)

- 20.Lewis N, Marshall J, Amelsberg A, Cohen RB, Stopfer P, Hwang J, Malik S (2006) A phase I dose escalation study of BIBW 2992, an irreversible dual EGFR/HER2 receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in a 3 week on 1 week off schedule in patients with advanced solid tumours. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2006 ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings Part I 24 (18S (June 20 supplement)):Abstract 3091

- 21.Yap TA, Vidal L, Adam J, Stephens P, Spicer J, Shaw H, Ang J, Temple G, Bell S, Shahidi M, Uttenreuther-Fischer M, Stopfer P, Futreal A, Calvert H, de Bono J, Plummer R. Phase I trial of the irreversible EGFR and HER2 kinase inhibitor BIBW 2992 in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(25):3965–3972. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.7278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trotti A, Colevas AD, Setser A, Rusch V, Jaques D, Budach V, Langer C, Murphy B, Cumberlin R, Coleman CN, Rubin P. CTCAE v3.0: development of a comprehensive grading system for the adverse effects of cancer treatment. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2003;13(3):176–181. doi: 10.1016/S1053-4296(03)00031-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, Wanders J, Kaplan RS, Rubinstein L, Verweij J, Van Glabbeke M, van Oosterom AT, Christian MC, Gwyther SG. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92(3):205–216. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Engelman JA, Janne PA. Mechanisms of acquired resistance to epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(10):2895–2899. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-2248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin NU, Winer EP, Wheatley D, Carey LA, Houston S, Mendelson D, Munster P, Frakes L, Kelly S, Garcia AA, Cleator S, Uttenreuther-Fischer M, Jones H, Wind S, Vinisko R, Hickish T. A phase II study of afatinib (BIBW 2992), an irreversible ErbB family blocker, in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer progressing after trastuzumab. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;133(3):1057–1065. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2003-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stopfer P, Schaefer HG, Amelsberg A, Huisman H, Eskens F, Gietema JA, Briscoe J, Lewis N, Cohen RB, Marshall J, Verweij J (2005) Pharmacokinetic results from two phase I dose escalation studies of once daily oral treatment with BIBW 2992, an irreversible dual EGFR/HER2 receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor in patients with advanced tumours. Proceedings, AACR-NCI-EORTC International Conference on Molecular Targets and Cancer Therapeutics:171(Abstract B172)

- 27.Burris HA, 3rd, Hurwitz HI, Dees EC, Dowlati A, Blackwell KL, O'Neil B, Marcom PK, Ellis MJ, Overmoyer B, Jones SF, Harris JL, Smith DA, Koch KM, Stead A, Mangum S, Spector NL. Phase I safety, pharmacokinetics, and clinical activity study of lapatinib (GW572016), a reversible dual inhibitor of epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinases, in heavily pretreated patients with metastatic carcinomas. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(23):5305–5313. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.16.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hidalgo M, Bloedow D. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics: maximizing the clinical potential of Erlotinib (Tarceva) Semin Oncol. 2003;30(3 Suppl 7):25–33. doi: 10.1016/S0093-7754(03)70012-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arora A, Scholar EM. Role of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in cancer therapy. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;315(3):971–979. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.084145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grunwald V, Hidalgo M. Developing inhibitors of the epidermal growth factor receptor for cancer treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95(12):851–867. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.12.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Herbst RS, Maddox AM, Rothenberg ML, Small EJ, Rubin EH, Baselga J, Rojo F, Hong WK, Swaisland H, Averbuch SD, Ochs J, LoRusso PM. Selective oral epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor ZD1839 is generally well-tolerated and has activity in non-small-cell lung cancer and other solid tumors: results of a phase I trial. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(18):3815–3825. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Loriot Y, Perlemuter G, Malka D, Penault-Lorca F, Boige V, Deutsch E, Massard C, Armand JP, Soria JC. Drug insight: gastrointestinal and hepatic adverse effects of molecular-targeted agents in cancer therapy. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2008;5(5):268–278. doi: 10.1038/ncponc1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hidalgo M, Siu LL, Nemunaitis J, Rizzo J, Hammond LA, Takimoto C, Eckhardt SG, Tolcher A, Britten CD, Denis L, Ferrante K, Von Hoff DD, Silberman S, Rowinsky EK. Phase I and pharmacologic study of OSI-774, an epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(13):3267–3279. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.13.3267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ranson M, Hammond LA, Ferry D, Kris M, Tullo A, Murray PI, Miller V, Averbuch S, Ochs J, Morris C, Feyereislova A, Swaisland H, Rowinsky EK. ZD1839, a selective oral epidermal growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitor, is well tolerated and active in patients with solid, malignant tumors: results of a phase I trial. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(9):2240–2250. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.10.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mom CH, Eskens FA, Gietema JA, Nooter K, De Jonge MJ, Amelsberg A, Huisman H, Stopfer P, De Vries EG, Verweij J. Phase I study with BIBW 2992, an irreversible dual tyrosine kinase inhibitor of epidermal growth factor receptor 1 (EGFR) and 2 (HER2) in a 2-week on, 2-week off schedule. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(18S):S3025. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lewis N, Marshall J, Amelsberg A, Cohen RB, Stopfer P, Hwang J, Malik S. A phase I dose escalation study of BIBW 2992, an irreversible dual EGFR/HER2 receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in a 3 week on 1 week off schedule in patients with advanced solid tumours. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(18S):3091. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller VA, Hirsh V, Cadranel J, Chen YM, Park K, Kim SW, Zhou C, Su WC, Wang M, Sun Y, Heo DS, Crino L, Tan EH, Chao TY, Shahidi M, Cong XJ, Lorence RM, Yang JC. Afatinib versus placebo for patients with advanced, metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer after failure of erlotinib, gefitinib, or both, and one or two lines of chemotherapy (LUX-Lung 1): a phase 2b/3 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:528–538. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70087-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang JC-H, Schuler MH, Yamamoto N, O’Byrne KJ, Hirsh V, Mok T, Geater SL, Orlov S, V., Tsai C-M, Boyer MJ, Su W-S, Bennouna J, Kato TG, V., Lee, K. H., Shah, R. N. H., Massey, D., Lorence, R. L., Shahidi, M., Sequist, L.V. (2012) LUX-Lung 3: A randomized, open-label, phase III study of afatinib versus pemetrexed and cisplatin as first-line treatment for patients with advanced adenocarcinoma of the lung harboring EGFR-activating mutations. J Clin Oncol 30 (suppl; abstr LBA7500)