Abstract

Plasma membrane cholesterol accumulation has been implicated in cellular insulin resistance. Given the role of the hexosamine biosynthesis pathway (HBP) as a sensor of nutrient excess, coupled to its involvement in the development of insulin resistance, we delineated whether excess glucose flux through this pathway provokes a cholesterolgenic response induced by hyperinsulinemia. Exposing 3T3-L1 adipocytes to physiologically relevant doses of hyperinsulinemia (250pM–5000pM) induced a dose-dependent gain in the mRNA/protein levels of 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-coenzyme A reductase (HMGR). These elevations were associated with elevated plasma membrane cholesterol. Mechanistically, hyperinsulinemia increased glucose flux through the HBP and O-linked β-N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc) modification of specificity protein 1 (Sp1), known to activate cholesterolgenic gene products such as the sterol response element-binding protein (SREBP1) and HMGR. Chromatin immunoprecipitation demonstrated that increased O-GlcNAc modification of Sp1 resulted in a higher binding affinity of Sp1 to the promoter regions of SREBP1 and HMGR. Luciferase assays confirmed that HMGR promoter activity was elevated under these conditions and that inhibition of the HBP with 6-diazo-5-oxo-l-norleucine (DON) prevented hyperinsulinemia-induced activation of the HMGR promoter. In addition, both DON and the Sp1 DNA-binding inhibitor mithramycin prevented the hyperinsulinemia-induced increases in HMGR mRNA/protein and plasma membrane cholesterol. In these mithramycin-treated cells, both cortical filamentous actin structure and insulin-stimulated glucose transport were restored. Together, these data suggest a novel mechanism whereby increased HBP activity increases Sp1 transcriptional activation of a cholesterolgenic program, thereby elevating plasma membrane cholesterol and compromising cytoskeletal structure essential for insulin action.

Increased caloric intake and/or obesity are currently the greatest predisposing risk factors for the development of type 2 diabetes (T2D). Recent study implicates increased nutrient flux through the hexosamine biosynthesis pathway (HBP) as an underlying basis for the development and exacerbation of insulin resistance and β-cell failure, hallmark events in the pathology of T2D. As such, a concerted research effort has been underway to gain mechanistic insight into how HBP activity results in desensitization of the glucose transport system. Marshall et al (1) first demonstrated that HBP activity was involved in the development of glucose-induced insulin resistance. Glucose entry into the HBP is catalyzed by the first and rate-limiting enzyme, glutamine:fructose-6-phosphate-amidotransferase (GFAT), which converts fructose-6-phosphate and glutamine into glucosamine-6-phosphate. Glucosamine-6-phosphate is subsequently metabolized, culminating in the production of UDP-N-acetylglucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc), the high-energy substrate for O-linked β-N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc) transferase, a nuclear and cytosolic enzyme that catalyzes the addition of GlcNAc to serine/threonine residues (2, 3).

In humans, polymorphisms in N-acetylglucosaminidase, which hydrolyzes O-GlcNAc moieties, is associated with increased risk for T2D (4), and skeletal muscle biopsies obtained from T2D individuals display markedly elevated levels of GFAT (5). Approximately 2-fold elevations in both mRNA and protein content of GFAT, with associated gains in the end product UDP-GlcNAc have been observed in palmitate-induced insulin-resistant human skeletal muscle (6). Additionally, other work suggests a significant role of adipose tissue HBP activity in the development of insulin resistance. For instance, adipocyte lipid binding protein 2 GFAT mice, overexpressing GFAT specifically in adipose tissue, have reduced whole-body glucose disposal and peripheral insulin resistance (7). In these mice, high-fat feeding does not further impair glucose disposal or change adipokine levels, supporting the role of the HBP in the development of high-fat diet-induced insulin resistance (8). Although the mechanistic basis for the HBP-induced insulin resistance remains unclear, we have found increased HBP activity increases plasma membrane cholesterol that compromises the cortical filamentous actin (F-actin) structure that is essential for movement of the glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) and glucose transport regulation (9, 10). In fact, several key metabolic derangements (eg, hyperinsulinemia, hyperlipidemia, and hyperglycemia), known to induce insulin resistance and accelerate T2D progression, increase HBP activity in cultured L6 myotubes and 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Furthermore, data suggest these derangements, via the HBP, provoke a cholesterolgenic response (9, 10). In particular, these studies found that inhibition of GFAT prevents an increased expression of 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-coenzyme A reductase (HMGR), gain in plasma membrane cholesterol, loss of cortical F-actin, and insulin resistance.

Interestingly, a key transcription factor involved in cholesterol synthesis, specificity protein 1 (Sp1), has been documented to be a target of the HBP (11). Emerging work suggests that although ordinarily functioning as a housekeeping transcription factor, Sp1 also plays a significant role in regulating expression of a host of metabolic genes in response to posttranslational modifications induced by insulin and other hormonal signaling (12). Through altering the O-GlcNAc and/or phosphorylation status of Sp1, insulin has been shown to dynamically regulate its subcellular localization, stability, and potentially its transcriptional activity (13). Moreover, in palmitate-induced insulin-resistant human skeletal muscle, an increase in Sp1 binding to DNA has been observed (6), suggesting that palmitate-induced elevations in HBP may up-regulate the activity of this transcription factor. These data, together with our previous observations that HBP inhibition prevents plasma membrane cholesterol accumulation, cytoskeletal defects, and insulin resistance induced by the diabetic milieu, suggested that the HBP activates a cholesterolgenic response by modulation of transcription factors involved in cholesterol synthesis. Here we tested this possibility and present data showing that O-GlcNAc modification of Sp1 increases this transcription factor's binding to the HMGR promoter and activates transcription of this key enzyme in the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway. Blocking Sp1-mediated activation of HMGR completely protects against hyperinsulinemia-induced membrane/cytoskeletal defects and impaired insulin-mediated glucose transport. These results illustrate a novel mechanism by which the modern lifestyle, abundant in excess nutrient intake, may impinge on glucose transport and contribute to the development of diabetes.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and treatments

Murine 3T3-L1 preadipocytes were purchased from Dr. Howard Green (Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts) and cultured as previously described (14). Briefly, 3T3-L1 preadipocytes were cultured in DMEM containing 25mM glucose and 10% calf serum in at 37°C at a 10% CO2 atmosphere. Confluent cultures were induced to differentiate into adipocytes as previously described (9). All studies were performed on adipocytes between 8 and 12 days post initiation of differentiation. The cells were left untreated or treated with insulin (250pM–5000pM) in serum-free DMEM medium for 12 hours. Overnight insulin incubations were limited to 12 hours to minimize complications on glucose transport due to glucose deprivation (15). Two pretreatment conditions were also tested. The first pretreatment included the presence of 20μM 6-diazo-5-oxo-l-norleucine (DON) during the overnight incubation. The second pretreatment used the Sp1 inhibitor mithramycin, which was also included during the overnight incubation at a concentration of 100nM. Acute insulin stimulation was performed by treating adipocytes with 100nM insulin during the last 30 minutes of the 12-hour period.

Subcellular fractionation

Purified adipocyte plasma membrane and endosomal membrane fractions were obtained using differential centrifugation as previously described (16). Purified fractions were resuspended in a detergent containing lysis buffer, and recovered protein content was determined using the Bradford method. Nuclear extracts were collected as previously described (17). Briefly, 3T3-L1 adipocytes were washed with PBS and collected in 2.0 ml of hypotonic buffer (10mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 10mM KCl, 1.5mM MgCl2, 1mM dithiothreitol containing 10mM leupeptin, 2mM pepstatin, 2mM aprotinin, and 0.5M phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF]). Lysates were prepared by passing the cells through a 22-gauge needle 5 times, followed by centrifugation at 800g for 10 minutes at 4°C. The pellet was then resuspended in 200 μl of buffer C (10mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 0.42M NaCl, 25% glycerol [vol/vol], 1.5mM MgCl2, 0.5mM EDTA containing 10mM leupeptin, 2mM pepstatin, 2mM aprotinin, and 0.5M PMSF). Proteins were extracted from the nuclei with gentle vortexing for 15 seconds every 10 minutes for 1 hour. The mixture was then centrifuged at full speed in a microcentrifuge at 4°C, and the supernatant consisting of nuclear proteins was collected for the Bradford method to determine protein content.

Actin analyses

Actin labeling of 3T3-L1 adipocytes was performed as previously described (9). Briefly, after treatments, cells were fixed in a 4% paraformaldehyde 0.2% Triton X-100 (vol/vol) solution containing PBS. After fixation, cells were incubated with 5 μg/ml of fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated phalloidin for 2 hours. All cell images were obtained using a Zeiss LSM 510 NLO confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, New York), and all microscope settings were identical between treatment groups. Immunofluorescent intensity was normalized to intensity from Syto60, a fluorescent nucleic acid stain (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oregon). Five cells per group per 3 separate experiments for a total of 15 cells were used in the analysis of the data.

Cholesterol analyses

Plasma membrane pellets obtained from differential centrifugation were resuspended in 0.2 ml of HEPES/EDTA/sucrose buffer, and cholesterol content was assayed using the Amplex Red cholesterol assay kit (Molecular Probes), as previously described (9). Briefly, 0.15 ml of the resuspended plasma membrane pellet was vigorously mixed with 3.0 ml of chloroform-methanol (2:1 vol/vol) for 10 minutes to extract cholesterol. The mixture was then centrifuged at 580g for 10 minutes followed by collection of 1 ml of the lower phase, which was evaporated at 100°C for 10 minutes. The residue was then reconstituted with 0.1 ml of an isopropranol-Triton X-100 solution (10:1 vol/vol), and 0.05 ml of the sample was incubated with 0.05 ml of Amplex Red cholesterol reaction buffer at 37°C for 30 minutes. After incubation, the absorbance was measured at 600 nm.

Protein analyses

Protein (30–50 μg) was resolved on a 7.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and immunoblotted with polyclonal rabbit HMGR (Millipore, Billerica, Massachusetts), sterol response element-binding protein 2 (SREBP2) (Abcam, Cambridge, Massachusetts), or monoclonal mouse SREBP1 (Abcam) followed by an IRDye 700DX or 800DX conjugated secondary (Rockland, Gilbertsville, Pennsylvania). Immunoblots were quantitated using a LI-COR Odyssey infrared imaging system (LI-COR, Lincoln, Nebraska). Immunoblots were normalized to β-actin for equal protein loading. For immunoprecipitation experiments, lysates from 3T3-L1 adipocytes treated with or without insulin and DON were collected using a Nonidet P-40 (NP-40) lysis buffer (25mM Tris [pH 7.4], 137mM NaCl, 10mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1% NP-40, 1% glycerol, containing 10mM leupeptin, 2mM pepstatin, 2mM aprotinin, and 0.5M PMSF). Whole-cell lysates were then prepared by centrifugation at 14 000 rpm at 4°C for 15 minutes. The Bradford assay was performed to ensure equal protein loading for immunoprecipitation analysis. Immunoprecipitation was carried out overnight with 1.25 mg protein and 2 μg Sp1 mouse monoclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, California). Samples were then incubated with 80 μl protein G agarose (Roche, Indianapolis, Indiana) for 1 hour with rotation at 4°C. Protein complexes were pelleted by centrifugation at 14 000 rpm at 4°C for 10 minutes, washed with NP-40 lysis buffer, and eluted with 200 μl Laemmli sample buffer containing β-mercaptoethanol and 0.1M dithiothreitol. Samples were then run on a 7.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and immunoblotted with an RL2 antibody (Thermo Scientific, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania). For Click-iT O-GlcNAC enzymatic labeling experiments, lysates prepared from 3T3-L1 adipocytes treated with hyperinsulinemia in the presence or absence of DON were immunoprecipitated as described above. Prior to elution, samples were resuspended in 200 μl 1% SDS, 20mM HEPES (pH 7.9) and labeled with biotin-alkyne using the Click-iT O-GlcNAc enzymatic labeling system and protein analysis detection kits (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California). The immunoprecipitated samples were then eluted as described above. Samples were then run on a polyacrylamide gel and analyzed using a streptavidin antibody (Abcam) to detect O-GlcNAc moieties on Sp1.

RNA analyses

3T3-L1 adipocytes treated with various concentrations of insulin with or without the presence of DON were lysed using a QIAGEN QIAshredder, and RNA was isolated using a QIAGEN RNeasy mini kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, California). RNA was reverse transcribed using the high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California). Reactions were performed in a 96-well plate using the ABI Prism 7000 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems). Each reaction contained the following: 12.5 μl SYBR Green (Applied Biosystems), 200nM of each primer, 3 μl cDNA, and ribonuclease-free water to a total volume of 25 μl. The 36B4 gene was used as a control and was amplified in parallel. Primers used for amplification of Hmgcr are shown in Table 1. The PCR conditions used were 95°C for 15 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds and 60°C for 40 seconds. Cycle threshold (Ct) values were obtained and normalized to 36B4. The ΔΔCt method was used to determine relative expression levels.

Table 1.

Primers Used for PCR Amplification in This Study

| Primer | Sequence (5′–3′) |

|---|---|

| pGL2B-Hmgcr | |

| Forward | TAGGTACCCATCCCCTGTTCCCCGCG |

| Reverse | TAAAGCTTGTCTCCAGCCAACGGAGC |

| ChIP-Hmgcr | |

| Forward | ACCCGTCATTGGTTGGCTCT |

| Reverse | CTCCCTAACAACCGCCAACT |

| ChIP-Srebf1 | |

| Forward | CCATCCCTGGCCCTTTAATCTAACGA |

| Reverse | TTCGGACTAGGCCCACGTTAAGGAAA |

| qPCR-Hmgcr | |

| Forward | TGTGGGAACGGTGACACTTA |

| Reverse | CTTCAAATTTTGGGCACTCA |

| qPCR-36B4 | |

| Forward | AAGCGCGTCCTGGCATTGTCT |

| Reverse | CCGCAGGGGCAGCAGTGGT |

Forward and reverse represent a pair of sense primers and antisense primers, respectively.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay

Treated 3T3-L1 adipocytes were fixed with 1% formaldehyde in PBS for 10 min. The reaction was then quenched by addition of 50mM glycine in PBS and subsequently washed two times with ice-cold PBS. Cells were then scraped in PBS plus protease inhibitor cocktail and centrifuged for 2 minutes at 2000 rpm. The pellet was resuspended in 500 μl chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) lysis buffer (50mM Tris [pH 8.1], 10mM EDTA, 1% SDS plus protease inhibitor cocktail) and sonicated (10 pulses of 30 seconds on, 30 seconds off) and centrifuged at 14 000 rpm at 4°C for 10 minutes. Chromatin size was checked by running on a nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel to ensure that the average size was between 200 and 500 base pairs. Fragmented chromatin preparations (100 μl) were then diluted with ChIP dilution buffer (Millipore), and an input sample was collected. Samples were precleared with 60 μl of ChIP blocked protein G-Agarose beads (Millipore) for 1 hour at 4°C with rotation prior to immunoprecipitation with antibodies to Sp1 (Santa Cruz) or IgG (Millipore) overnight. Samples were then incubated with 60 μl of protein G-Agarose beads for 1 hour, and then protein-DNA complexes were collected by centrifugation. Immunoprecipitates were washed in low-salt immune complex wash buffer, high-salt immune complex wash buffer, LiCl immune complex wash buffer, and 2 washes in Tris/EDTA buffer (Millipore) (5 minutes each). Immune complexes were then eluted with elution buffer (1% SDS, 100mM NaHCO3) and reverse cross-linked with the addition of 8 μl of 5M NaCl at 65°C overnight. Successful immunoprecipitation was ensured by running samples on a polyacrylamide gel and probing with the Sp1 antibody. After ribonuclease A and proteinase K treatment, phenol/chloroform was used to purify DNA that was used as a template for quantitative PCR (qPCR) under the following conditions: 15 minutes at 95°C followed by 35 cycles of 15 seconds at 95°C, 30 seconds at 50°C, and 34 seconds at 60°C. The fold enrichment method was used to quantitate Ct values. Subsequent nondenaturing gel electrophoresis was performed on samples subjected to qPCR to confirm the product. Dissociation curves were also performed to ensure a single product was formed, and an additional aliquot of DNA was subjected to nanodrop to ensure ratio of absorbance at 260 and 280 nm was between 1.8 and 2.0. Primers for qPCR analysis are described in Table 1.

Plasmids and luciferase reporter assay

To define the role of increased transcription factor binding in driving Hmgcr transcription, the proximal promoter sequence (−284 to +36) was PCR amplified from mouse genomic DNA. Promoter fragments were sequenced and cloned into pGL2B luciferase reporter plasmids (Promega, Madison, Wisconsin). Differentiated adipocytes were electroporated (0.16 kV and 960 μF) as previously described (9). Briefly, cells were trypsinized and pelleted by centrifugation at 1000 rpm. Pellets were resuspended in PBS and repelleted. Pellets were then resuspended in 1.0 ml PBS. For transfection, 50 μg of Hmgcr pGL2B and 50 μg of phrl-minTK (Renilla) plasmid were used with a concentration of approximately 1 × 107 cells/0.5 ml. A single pulse was then applied using a Gene Pulser (Bio-Rad, Hercules, California; 1652076). The electroporated cells were then allowed to recover and plated into a 24-well plate. Experiments were started 16–18 hours after electroporation by placing cells in the appropriate medium. After treatments, cells were lysed and assayed for promoter activity using the dual-luciferase reporter assay system (Promega). Firefly luciferase activities were normalized to Renilla luciferase activity to control for differences in transfection efficiency, and 10μM mevastatin was used as a positive control for these experiments.

Glucose transport assay

Glucose uptake assays were performed as previously described (9). Briefly treated cells were incubated in a KRPH buffer (136mM NaCl, 20mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 5mM sodium phosphate [pH 7.4], 4.7mM KCl, 1mM MgSO4, 1mM CaCl2) for 15 minutes. Cells were then left untreated or stimulated with 100nM insulin for 30 minutes and exposed to 50μM 2-deoxyglucose containing 0.5 μCi 2-[3H]deoxyglucose (PerkinElmer, Waltham, Massachusetts) in the absence or presence of 20μM cytochalasin B. After 10 minutes, uptake was terminated by aspiration and quenched with the addition of 1.0 ml of 10μM cytochalasin B. Cells were solubilized in 0.2N NaOH, and [3H] was measured by liquid scintillation. Counts were normalized to total cellular protein, determined by the Bradford method.

Statistical analysis

Values presented are means ± SEM. The significance of differences between means was evaluated by repeated-measures ANOVA. Where a difference was indicated by ANOVA, a Newman-Keuls post hoc test was conducted to compare differences between groups. Statistical comparisons of the fold or percent change of Hmgcr expression, Sp1 O-linked glycosylation, and nuclear SREBP1 content from control were performed by two-tailed Student's t test analysis. GraphPad Prism version 5 software was used for all analyses. P < .05 was considered significant.

Results

Pathophysiological hyperinsulinemia provokes cholesterol synthesis

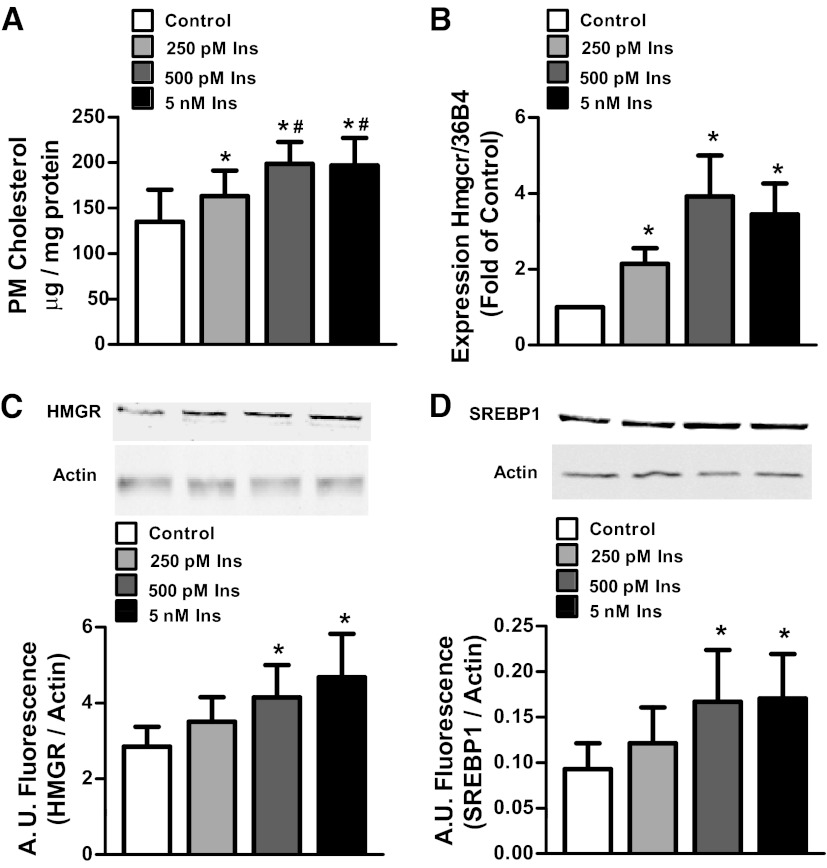

Studies have demonstrated that hyperinsulinemia induces cellular insulin resistance via increasing plasma membrane cholesterol. This, in turn, reduces cortical F-actin, essential for proper GLUT4 translocation (9, 10). The importance of understanding the molecular mechanism by which hyperinsulinemia potentiates insulin resistance is underscored by data conducted in nondiabetic individuals that show that hyperinsulinemia after a glucose load is tightly coupled to reduced insulin-mediated glucose uptake (18). Because physiological hyperinsulinemia is defined by levels of insulin between 187pM and 4.2nM (19), it was first probed whether these relevant doses of insulin would increase plasma membrane cholesterol in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Overnight exposure of cells to 250pM, 500pM, and 5nM insulin resulted in a 20%, 45%, and 43% increase in plasma membrane cholesterol, respectively, compared with control (Figure 1A). Note that the increases in plasma membrane cholesterol induced by 500pM and 5nM were not statistically different from each other yet were statistically greater than the increase induced by 250pM.

Figure 1.

Pathophysiological hyperinsulinemia induces a cholesterolgenic response. Cells were treated with or without 250pM, 500pM, or 5nM insulin (Ins) for 12 hours. Values are mean ± SEM from 3 to 8 experiments. A, Plasma membrane (PM) cholesterol content. B, Hmgcr mRNA expression. C, HMGR protein content. D, SREBP1 protein content. *P < .05 vs untreated control; #P < .05 vs 250pM insulin. A.U. indicates arbitrary units.

We next assessed the effects of the varying doses of chronic insulin on the status of HMGR, the rate-limiting enzyme in cholesterol synthesis. Consistent with hyperinsulinemia modulating the transcriptional activity of the gene, 250pM, 500pM, and 5nM insulin increased mRNA levels of Hmgcr (Figure 1B). This was consistent with an observed gain in HMGR protein levels in the cells chronically exposed to 500pM and 5nM, but not 250pM, insulin (Figure 1C). Because HMGR is known to be regulated by SREBP2 and, albeit to a lesser extent, SREBP1, total levels of these transcription factors were examined. Although total levels of SREBP2 were unchanged (data not shown), total SREBP1 was found to be elevated by 500pM and 5nM, but not 250pM, insulin (Figure 1D). Although the SREBP1c isoform is most abundant in adipose tissue, the antibodies used in this study could not differentiate between SRERBP1a and SREBP1c (20). All subsequent analyses were performed with 500pM insulin.

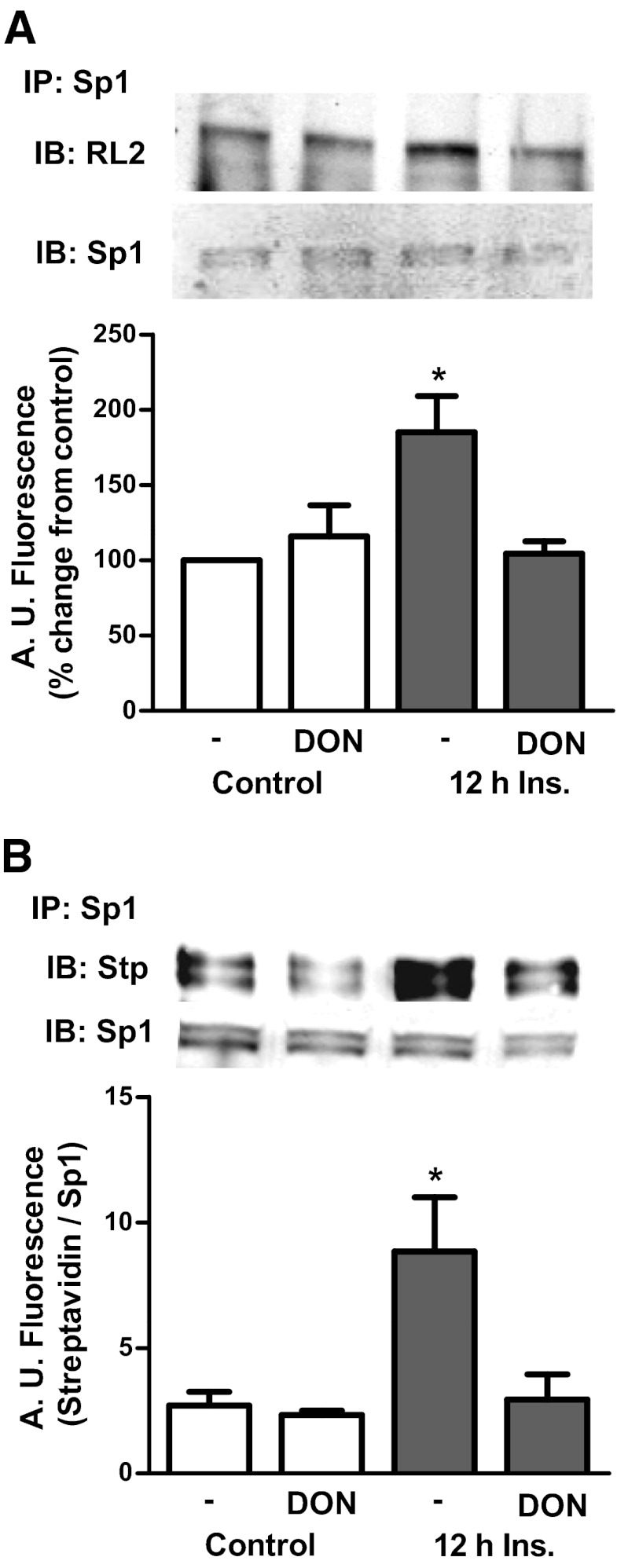

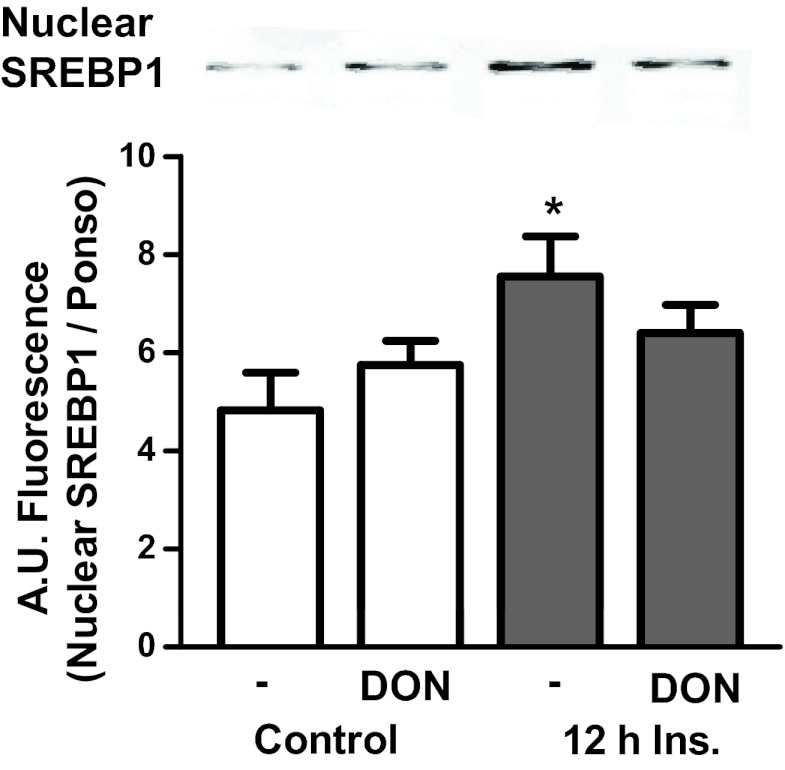

O-Linked glycosylation alters SREBP1 localization

To test whether the 500pM dose of insulin induced alterations in cholesterolgenic transcription factors, the glycosylation status of Sp1, a transcription factor that augments synthesis of SREBP1, was examined (21, 22). Immunoprecipitates of Sp1 from insulin-treated adipocytes displayed a marked increase in O-linked glycosylation compared with control cells (Figure 2A). In contrast, inhibition of the HBP with 20μM DON completely prevented this elevation in Sp1 O-linked glycosylation (Figure 2A). DON treatment did not affect the control level of O-linked glycosylation of Sp1. The changes in O-linked glycosylation of Sp1 were confirmed with the Click-iT O-GlcNAc enzymatic labeling system that allowed a more sensitive detection of the hyperinsulinemia-induced and DON-inhibited increase in O-linked glycosylation of Sp1 (Figure 2B). Although O-linked glycosylation may regulate nuclear localization of transcription factors (23), an increase in total nuclear content of Sp1 was not observed under these hyperinsulinemic conditions (data not shown), consistent with other reports that Sp1 is constitutively localized in the nucleus (24). However, hyperinsulinemia did result in a 54% gain in the nuclear, active form of SREBP1 (Figure 3). Consistent with the HBP provoking this gain in nuclear SREBP1, DON treatment strongly trended (P = .07) to prevent this increase (Figure 3). HBP inhibition had no effect on the localization of SREBP1 under control conditions.

Figure 2.

Hyperinsulinemia provokes O-linked glycosylation of Sp1. Lysates from cells treated with or without 500pM insulin (Ins) and/or 20μM DON were immunoprecipitated with an Sp1 antibody to detect O-linked glycosylation. A, Eluted samples were immunoblotted (IB) with an RL2 antibody. B, Immunoprecipitates were subjected to enzymatic labeling with a Click-iT kit and immunoblotted with streptavidin (Stp) antibody. Values are mean ± SEM from 4 independent experiments. *, P < .05 vs untreated control. A.U. indicates arbitrary units.

Figure 3.

Hyperinsulinemia provokes nuclear localization of SREBP1. Cells treated with or without 500pM insulin (Ins) and/or 20 μM DON were isolated and nuclear proteins were extracted. Nuclear extracts were then immunoblotted with an antibody for SREBP1. Values are mean ± SEM from 4 independent experiments. *P < .05 vs untreated. A.U. indicates arbitrary units.

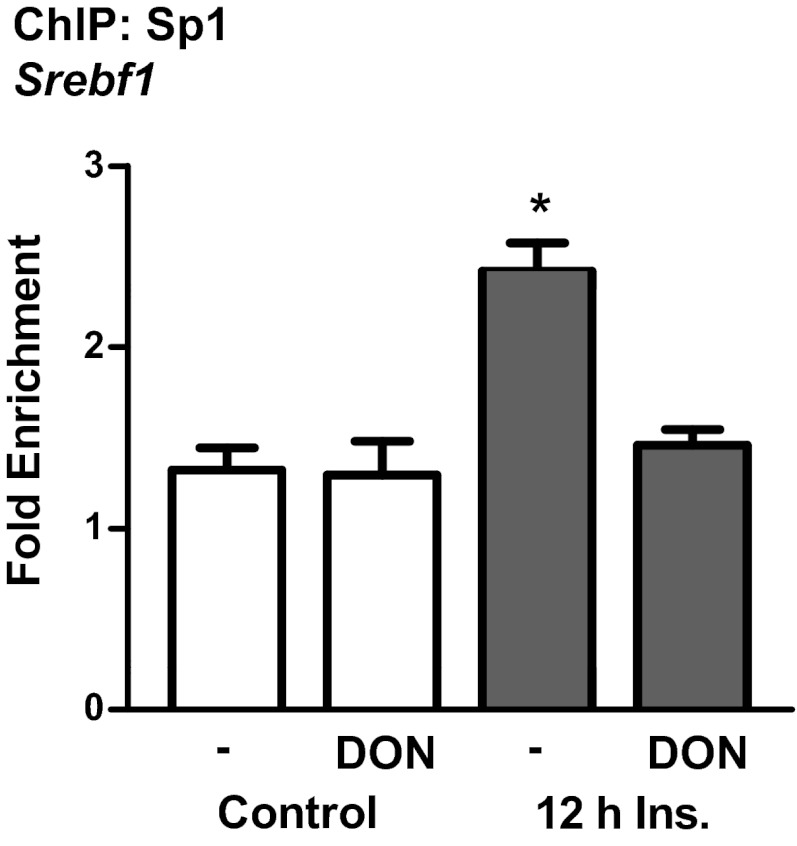

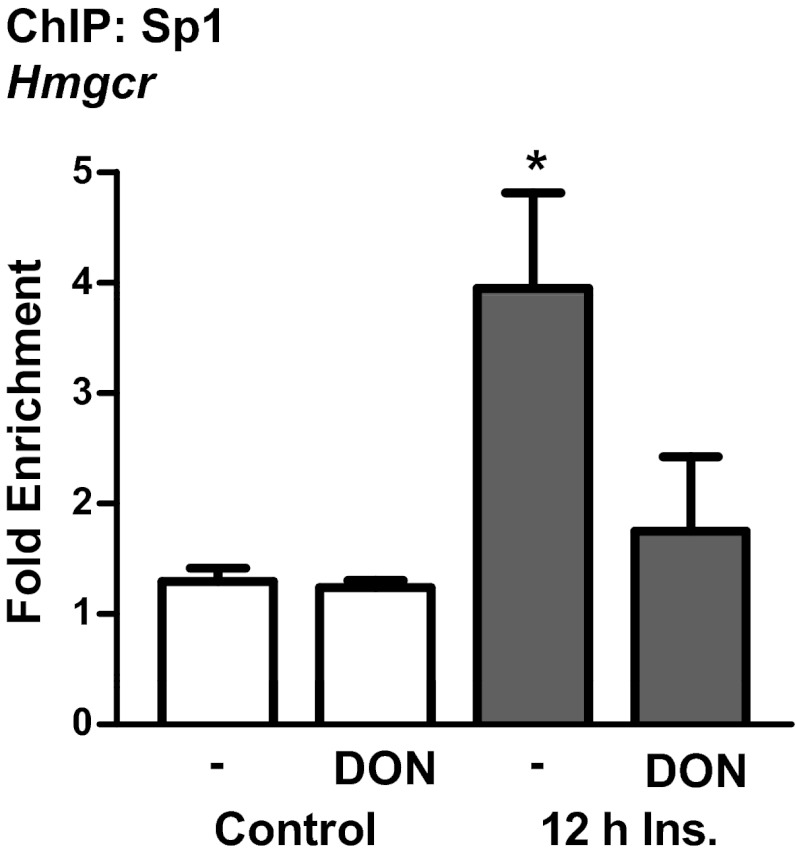

Hyperinsulinemia-induced O-GlcNAc of Sp1 increases transcription factor binding to DNA

Taken together, these results led to the hypothesis that elevated O-linked glycosylation of Sp1 induced by insulin may result in the transactivation of the gene Srebf1 for SREBP1 leading to the up-regulation of genes involved in cholesterol synthesis, such as the gene Hmgcr for HMGR. Previous studies have identified that many SRE-responsive genes contain binding sites for Sp1, including Srebf1 (25–28). ChIP assays were used to determine whether hyperinsulinemia affects binding of Sp1 to Srebf1. Results from these assays revealed that hyperinsulinemia treatment resulted in an approximate 2-fold increase in the binding affinity of Sp1 toward the promoter region of Srebf1 (Figure 4). The hyperinsulinemia-induced increase in Sp1 binding was abrogated by blocking the HBP pathway with DON (Figure 4). Interestingly, an Sp1-like binding site has recently been proposed in the promoter of Hmgcr (29). ChIP also demonstrated that hyperinsulinemia resulted in a 4-fold increase in Sp1 binding to the Hmgcr promoter, and this was blocked by DON (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Hyperinsulinemia-induced endogenous Sp1-DNA–binding activity is prevented by DON. ChIP was performed on 3T3-L1 adipocytes treated with or without 500pM insulin (Ins) and/or 20μM DON. Purified DNA and primers specific to the Sp1-binding site in the promoter region of Srebf1 were used for qPCR. Ct values from qPCR were normalized to the background IgG antibody using the fold enrichment method. Values are mean ± SEM from 3 independent experiments. *P < .05 vs control.

Figure 5.

Sp1 binds to the promoter region of Hmgcr and its insulin-induced increased affinity is prevented by DON. ChIP was performed on 3T3-L1 adipocytes treated with or without 500pM insulin (Ins) and/or 20μM DON. Purified DNA and primers specific to the Sp1-binding sites in the promoter region of Hmgcr were used for qPCR. Ct values from qPCR were normalized to the background IgG antibody using the fold enrichment method. Values are mean ± SEM from 4 independent experiments. *P < .05 vs control.

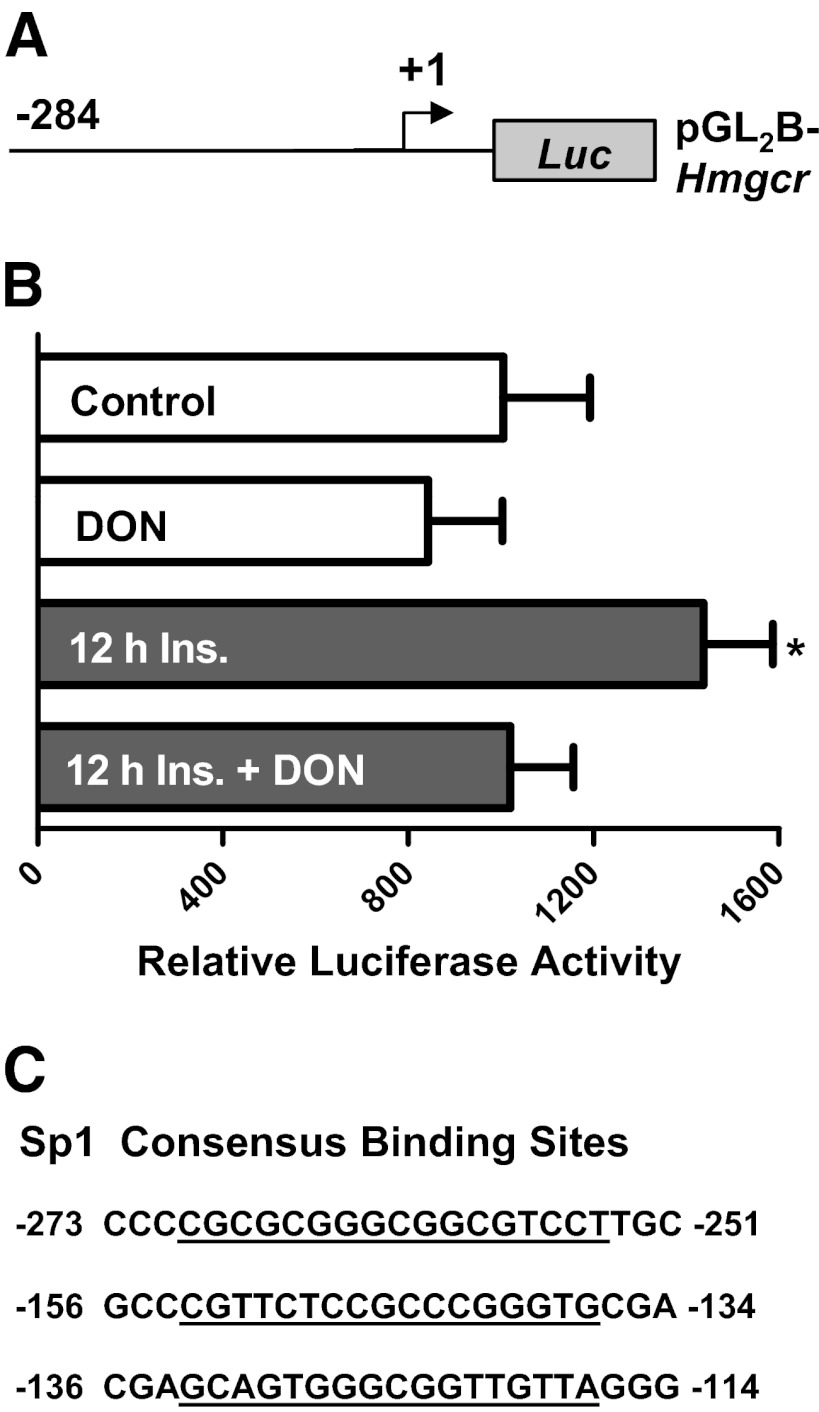

Hyperinsulinemia promotes transcriptional activation of Hmgcr

Because the transcriptional regulation of Srebf1 has been studied extensively, (22, 30, 31) whereas regulation of Hmgcr is incompletely understood, we sought to understand the role of the Sp1-binding site in the Hmgcr promoter. Plasmids containing the coding sequence of Hmgcr coupled to luciferase (Figure 6A) were electroporated into 3T3-L1 adipocytes to determine the role of hyperinsulinemia-induced Sp1 binding on promoter activity. In cells chronically exposed to 500pM insulin, Hmgcr promoter activity was elevated by ∼50% compared with control cells (Figure 6B). Consistent with the ChIP data, DON also blocked the hyperinsulinemia-mediated increase in promoter activity (Figure 6B). The 3 consensus binding sites of Sp1 were identified in the Hmgcr promoter region analyzed by in silico analysis with MatInspector (Figure 6C). Taken together, these results suggest that hyperinsulinemia-induced O-linked glycosylation of Sp1 results in activation of Srebf1 and Hmgcr to promote a cholesterolgenic program that provokes a gain in plasma membrane cholesterol.

Figure 6.

Hyperinsulinemia promotes and DON protects against transcriptional activation of the Hmgcr promoter. A, Hmgcr pGL2B and phrl-minTK construct was transfected into 3T3-L1 adipocytes. B, After transfection, cells were left untreated or treated with 500pM insulin (Ins) in the presence or absence of DON, and luciferase activity was measured relative to Renilla. Values are mean ± SEM from 3 to 5 experiments. C, The Sp1-binding sites in the Hmgcr promoter region. *P < .05 vs control.

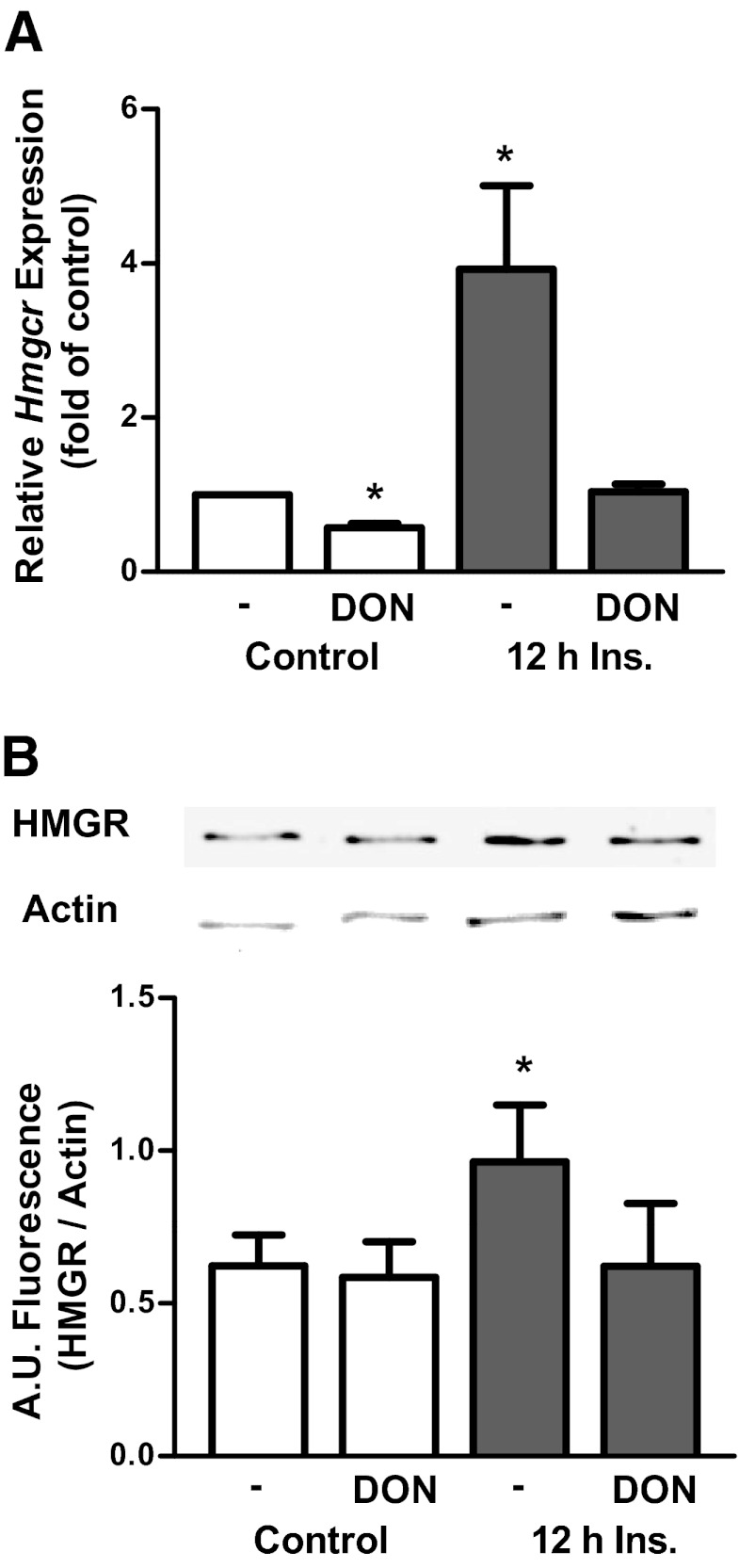

Inhibition of HBP ablates the cholesterolgenic response

To test whether DON protects against the transcriptional activation of a cholesterolgenic program, mRNA levels of Hmgcr were examined. Hmgcr mRNA obtained from cells treated with 500pM insulin displayed the characteristic 4-fold increase over mRNA from control cells (Figure 7A). Treatment with DON completely abrogated the insulin-induced transcriptional activation of Hmgcr. Interestingly, in control cells, DON also slightly, but significantly, lowered Hmgcr mRNA levels by 43% (Figure 7A). In addition to measuring mRNA, the effect of DON on HMGR protein levels was also tested. As can be seen in Figure 7B, DON prevented the hyperinsulinemia-induced gain in HMGR. In contrast to the mRNA data, DON did not affect control HMGR protein levels (Figure 7B), indicating the mRNA levels may not be precisely coupled to the protein content.

Figure 7.

Inhibition of the HBP pathway protects against the cholesterolgenic response. 3T3-L1 adipocytes were left untreated or treated with 500pM insulin (Ins) in the presence or absence of DON. Values are mean ± SEM from 5 to 8 experiments. A, Hmgcr mRNA expression. B, HMGR protein content. *P < .05 vs control. A.U. indicates arbitrary units.

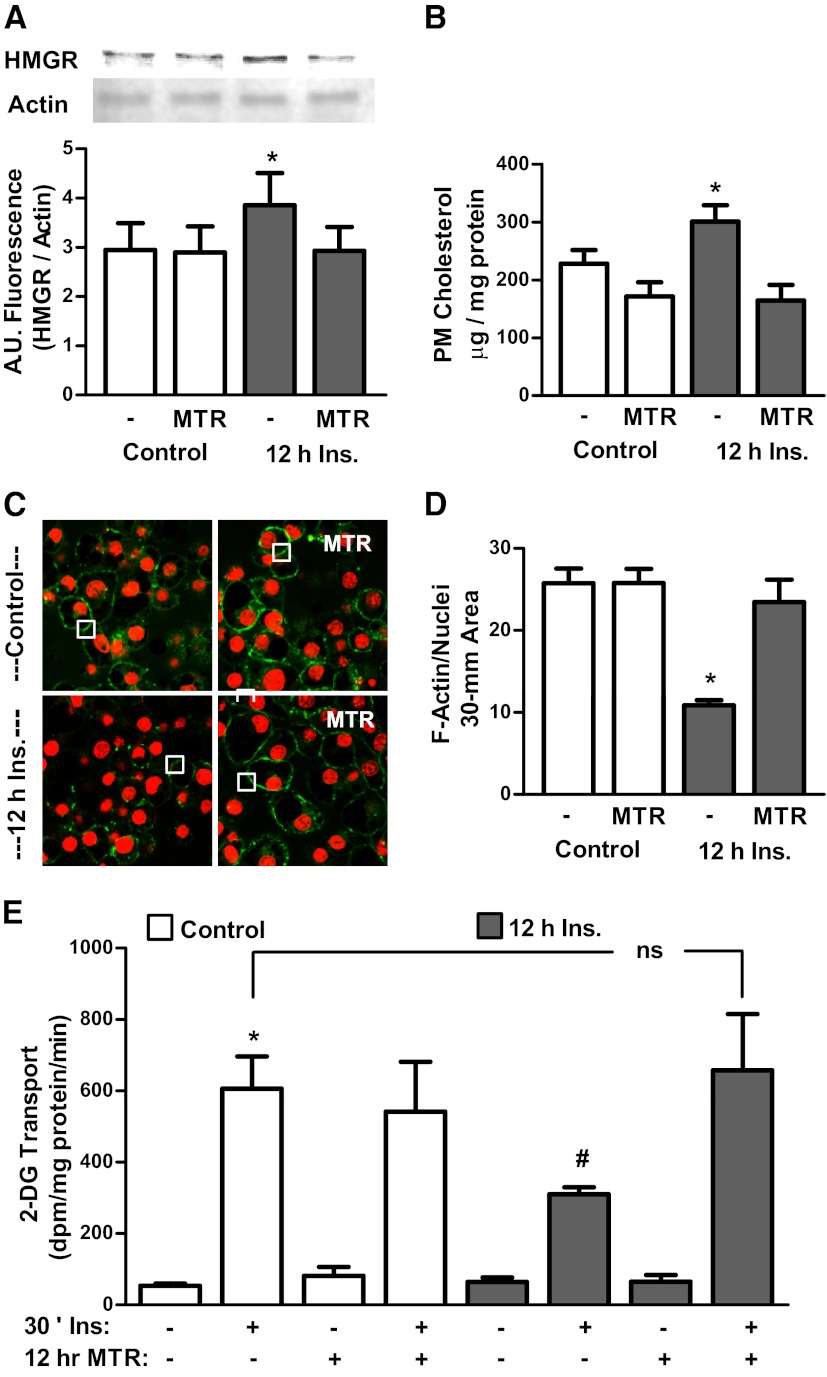

Sp1 inhibition protects against hyperinsulinemia-induced glucose transport dysfunction

With data suggesting that Sp1 plays a critical role in mediating hyperinsulinemia-induced cholesterol synthesis, we tested the effect of inhibiting Sp1 binding to DNA with mithramycin, a specific Sp1/DNA-binding inhibitor (32) on HMGR expression, plasma membrane cholesterol, F-actin cytoskeletal structure, and glucose transport. As reported previously (32), mithramycin treatment did not have any effects on cell viability, although it clearly prevented the hyperinsulinemia-induced gain in HMGR protein (Figure 8A). Concurrently, mithramycin protected against the hyperinsulinemia-induced gain in plasma membrane cholesterol (Figure 8B), loss in cortical F-actin (Figure 8, C and D), and impaired insulin-stimulated glucose transport (Figure 8E). Neither mithramycin nor hyperinsulinemia affected basal levels of glucose transport.

Figure 8.

Inhibition of Sp1-binding activity protects against cellular cholesterol accrual and insulin resistance. Cells were treated with or without 500pM insulin (Ins) in the presence of absence of the Sp1-binding inhibitor mithramycin (MTR). Values are mean ± SEM from 3 to 5 experiments. A, HMGR protein content. B, Plasma membrane (PM) cholesterol. C, F-actin confocal images. D, quantification of F-actin analysis, normalized to Syto60 (4–6 images were collected per experiment). E, 2-Deoxyglucose (2-DG) uptake. *P < .05 vs control; #P < .05 vs all other 30-minute insulin groups; ns, nonsignificant. A.U. indicates arbitrary units.

Discussion

Although the mechanisms by which excess nutrient intake can contribute to glucose intolerance are complex and highly interdependent, it is clear that the HBP plays a central role in the etiology of insulin resistance. Previous study in our lab has demonstrated that hyperinsulinemia provokes cholesterol accrual that compromises the cytoskeletal architecture required for glucose transport (9, 10). Data presented here suggest a mechanism by which elevated glucose flux through the HBP, driven by hyperinsulinemia, may activate anabolic processes such as cholesterol synthesis via modification of transcription factors. We further report that low pathophysiologically relevant doses of insulin are sufficient to provoke this response. This is consistent with other studies that have shown that low doses of insulin are sufficient to induce insulin resistance (1, 33). Although the 250pM dose of insulin resulted in a submaximal gain in plasma membrane cholesterol, it did not have any effect on the generation of HMGR. Furthermore, it did not result in an activation of SREBP1. This suggests that this low dose would have marginal, if any, effects on glucose uptake. Although this dose is in the upper quartile of what was defined by the San Antonio Heart study of ∼3000 participants as hyperinsulinemia, it also fell within the range of fasting insulin levels (6pM–300pM), suggesting that this dose is perhaps too low to elevate cholesterol levels sufficiently to induce perturbations in insulin sensitivity in our model system. Another consideration is that the 3T3-L1 adipocyte cell culture system has been reported to have notable levels of intracellular insulin-degrading enzyme activity that may potentially lower levels of insulin present over time (34). Regardless of the possible effects of the degrading enzyme, the observed effects with concentrations of insulin akin to those in vivo suggests degradation rates were likely negligible in this system.

Interestingly, although hyperinsulinemia resulted in elevated O-GlcNAc modification of Sp1, this did not result in alterations in its localization as others have observed in other cell types (35, 36). However, Sp1 is primarily localized to the nucleus, thus making small changes in Sp1 localization difficult to detect by either immunoblotting or immunofluorescence (24). Nevertheless, SREBP1, known to be regulated by Sp1 (21, 22), was found elevated, albeit small, perhaps due to subsequent degradation, in nuclear fractions upon treatment with hyperinsulinemia. Potentially, the observed elevation in SREBP1 in the nucleus with insulin could be due to newly synthesized SREBP1 because Sp1 is known to promote SREBP1 synthesis (21, 22). Although this cannot be excluded as a possibility, further study conducted with DON demonstrates that it is sufficient to return cholesterol levels to control conditions, suggesting the importance of combinatorial interactions between Sp1 and SREBP1 in regulating cholesterol synthesis.

Since the discovery that Sp1 was modified by O-GlcNAc, increasing its stability (11), several reports have hypothesized that this modification might induce alterations in binding to DNA and promoter activity (37–39). Clinical findings have highlighted the importance of Sp1 binding to DNA because mutations in the Sp1-binding sites have been found to correlate with a significant risk for the development of diabetic complications (40). In the context of provoking a cholesterolgenic response, ChIP analyses demonstrated that hyperinsulinemia-induced elevations in O-GlcNAc on Sp1 translated into its increased binding affinity to both Hmgcr and Srebf1. Previous study has shown that Srebf1 contains 5 Sp1-binding sites that, in conjunction with SREBP1, liver X receptor (LXR), and nuclear factor Y, drive its expression (21, 22, 30, 41). This result is in congruence with the nuclear extractions demonstrating elevations in SREBP1 protein content, suggesting that O-GlcNAc-modified Sp1 binding to Srebf1 may promote its activation by accrual in the endosomal compartments, leading to the increased interaction with the activating site 1 and 2 proteases. This cleavage of endosomal SREBP1 would result in its redistribution to the nucleus, where it could interact in collaboration with Sp1 bound to Hmgcr leading to altered transcriptional activity. Additionally, a new study has demonstrated that LXR is also modified by O-GlcNAc, resulting in increased binding to and activity of the promoter of Srebf1 (42). This lends further support that O-GlcNAcylation could activate a cholesterolgenic response by activating SREBP1 through increasing the activity of both Sp1 and LXR.

A potential caveat to studying how O-GlcNAc of Sp1 alters its binding affinity to cholesterolgenic genes is that the RL2 antibody and Click-iT approaches used to detect O-GlcNAc do not distinguish between different sites that are modified by O-GlcNAc. To date, Sp1 is known to contain at least 8 residues that can be modified by O-GlcNAc, with a majority being in the DNA-binding domain (43). Five sites of O-GlcNAc modification have been identified in the zinc finger DNA-binding domain of Sp1, and mutating these sites to alanine resulted in reduced basal transcriptional activity (44). In contrast, mutagenesis of a peptide derived from the Sp1 activation domain also suggested that O-GlcNAc modification in this region inhibits protein-protein interactions necessary for transcriptional activation (45, 46). This may explain the only slight elevation in Hmgcr promoter activity observed. A limitation of the luciferase assay was that site-directed mutagenesis was not performed to alter the binding site of Sp1 to the promoter. Such future studies are warranted and could provide an explanation for the precise role of Sp1 in the regulation of synthesis of HMGR protein.

The observation that HMGR protein levels were elevated with hyperinsulinemia treatment and corrected with HBP inhibition was somewhat perplexing given the negative feedback regulation of HMGR by cholesterol. Given that HMGR contains a sterol-sensing domain that upon binding to cholesterol or cholesterol intermediates results in its degradation, a potential explanation could be that cholesterol trafficking to the endoplasmic reticulum is impaired with hyperinsulinemia and corrected with HBP inhibition. However, our recent work indicates that endosomal cholesterol levels are also elevated by hyperinsulinemia (47). Although our data do not exclude the possibility that the degradation of HMGR may become impaired, a potential hypothesis is that the rate of turnover is not sufficient to overcome the increased rate of synthesis. Another novel explanation for cholesterol accumulation comes from a new study by the Osborne laboratory suggesting that SREBP activation may provoke macro-autophagy, or the breakdown or recycling of cholesterol esters and triglycerides stored in lipid droplets (48). However, this process has been linked to SREBP2 rather than SREBP1, and we did not observed any changes in SREBP2 in the current study. Regardless, inhibition of HBP with DON attenuated cholesterol synthesis at the level of transcription, providing further evidence that the insulin-induced defects are functioning at the transcriptional level to result in gains in HMGR and plasma membrane cholesterol content.

The central role of Sp1 in triggering the cholesterolgenic response was demonstrated using mithramycin to inhibit Sp1 binding to DNA. This drug is known to be highly selective to GC-rich sequences of DNA, competitively inhibiting Sp1 binding without affecting the binding of other Sp1 family members (eg, Sp3) (49). In 3T3-L1 adipocytes, mithramycin abrogated hyperinsulinemia-mediated increases in HMGR protein levels and restored plasma membrane cholesterol to levels observed in control cells (Figure 8). Additionally, the attenuation of the cholesterolgenic response was associated with a restoration of the cortical F-actin meshwork necessary for the proper trafficking of GLUT4 to the plasma membrane. Glucose uptake experiments demonstrated that mithramycin treatment protected against the hyperinsulinemia-mediated decrease in glucose transport (Figure 8). Although a dose-response curve was not performed in the current study, impairment of this well-characterized (9, 33, 50–52) maximal stimulation would seem to suggest the effect of lower doses of insulin would also be impaired. This affect could not be attributed to reduced O-GlcNAc on Sp1 resulting in its decreased activity because immunoprecipitation experiments demonstrated that Sp1 modification was not mitigated with mithramycin A treatment (data not shown). Together, these results suggest Sp1 may play a critical role in dysregulation of cholesterol synthesis that occurs with altered nutrient delivery to the cell.

In terms of human health, our data suggest that Sp1 may be a potential therapeutic target for improving insulin sensitivity. Other studies with mithramycin have shown that it may also have beneficial effects on hepatic insulin signaling by inhibiting the negative regulator of signaling, protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (53). Moreover, Sp1-binding sites have been found on the promoter regions of the genes encoding leptin, resistin, and adiponectin, adipokines that regulate insulin sensitivity. Changes in Sp1 binding and/or activity with HBP-activating conditions have been proposed to modulate the activity of these genes in vitro and in vivo (39, 40, 54), suggesting that specific inhibition of O-GlcNAc modification of Sp1 would also have beneficial effects by inhibiting the expression of these molecules. Of further interest are reports that suggest that a potential mechanism of the insulin-sensitizing action of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor agonists is to specifically inhibit O-GlcNAc modification of Sp1 (32). Taken together, these studies suggest that Sp1 may represent a critical signaling nexus for regulating insulin sensitivity.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DK082773 (to J.S.E.) and DK061130 (to B.P.H.) and an Indiana University School of Medicine Moenkhaus Endowment (to B.A.P.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- ChIP

- chromatin immunoprecipitation

- Ct

- cycle threshold

- DON

- 6-diazo-5-oxo-l-norleucine

- F-actin

- filamentous actin

- GFAT

- glutamine:fructose-6-phosphate-amidotransferase

- GLUT4

- glucose transporter 4

- HBP

- hexosamine biosynthesis pathway

- HMGR

- 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-coenzyme A reductase

- LXR

- liver X receptor

- NP-40

- Nonidet P-40

- O-GlcNAc

- O-linked β-N-acetylglucosamine

- PMSF

- phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR

- Sp1

- specificity protein 1

- SREBP2

- sterol response element-binding protein 2

- T2D

- type 2 diabetes

- UDP-GlcNAc

- UDP-N-acetylglucosamine.

References

- 1. Marshall S, Bacote V, Traxinger RR. Discovery of a metabolic pathway mediating glucose-induced desensitization of the glucose transport system. Role of hexosamine biosynthesis in the induction of insulin resistance. J Biol Chem. 1991;266(8):4706–4712 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kreppel LK, Blomberg MA, Hart GW. Dynamic glycosylation of nuclear and cytosolic proteins. Cloning and characterization of a unique O-GlcNAc transferase with multiple tetratricopeptide repeats. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(14):9308–9315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lubas WA, Frank DW, Krause M, Hanover JA. O-Linked GlcNAc transferase is a conserved nucleocytoplasmic protein containing tetratricopeptide repeats. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(14):9316–9324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lehman DM, et al. A single nucleotide polymorphism in MGEA5 encoding O-GlcNAc-selective N-acetyl-beta-D glucosaminidase is associated with type 2 diabetes in Mexican Americans. Diabetes. 2005;54(4):1214–1221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yki-Jarvinen H, Daniels MC, Virkamaki A, et al. Increased glutamine:fructose-6-phosphate amidotransferase activity in skeletal muscle of patients with NIDDM. Diabetes. 1996;45(3):302–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Weigert C, Klopfer K, Kausch C, et al. Palmitate-induced activation of the hexosamine pathway in human myotubes: increased expression of glutamine:fructose-6-phosphate aminotransferase. Diabetes. 2003;52(3):650–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hazel M, Cooksey RC, Jones D, et al. Activation of the hexosamine signaling pathway in adipose tissue results in decreased serum adiponectin and skeletal muscle insulin resistance. Endocrinology. 2004;145(5):2118–2128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cooksey RC, McClain DA. Increased hexosamine pathway flux and high fat feeding are not additive in inducing insulin resistance: evidence for a shared pathway. Amino Acids. 2011;40(3):841–846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bhonagiri P, Pattar GR, Habegger KM, et al. Evidence coupling increased hexosamine biosynthesis pathway activity to membrane cholesterol toxicity and cortical filamentous actin derangement contributing to cellular insulin resistance. Endocrinology. 2011;152(9):3373–3384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Habegger KM, Penque BA, Sealls W, et al. Fat-induced membrane cholesterol accrual provokes cortical filamentous actin destabilisation and glucose transport dysfunction in skeletal muscle. Diabetologia. 2012;55(2):457–467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Han I, Kudlow JE. Reduced O glycosylation of Sp1 is associated with increased proteasome susceptibility. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17(5):2550–2558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Solomon SS, Majumdar G, Martinez-Hernandez A, Raghow R. A critical role of Sp1 transcription factor in regulating gene expression in response to insulin and other hormones. Life Sci. 2008. 83(9–10):305–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Majumdar G, Wright J, Markowitz P, et al. Insulin stimulates and diabetes inhibits O-linked N-acetylglucosamine transferase and O-glycosylation of Sp1. Diabetes. 2004;53(12):3184–3192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Green H, Meuth M. An established pre-adipose cell line and its differentiation in culture. Cell. 1974;3(2):127–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. van Putten JP, Krans HM. Glucose as a regulator of insulin-sensitive hexose uptake in 3T3 adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 1985;260(13):7996–8001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Elmendorf JS. Fractionation analysis of the subcellular distribution of GLUT-4 in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Methods Mol Med. 2003;83:105–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dugail I. Transfection of adipocytes and preparation of nuclear extracts. Methods Mol Biol. 2001;155:141–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kim SH, Reaven GM. Insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia: you can't have one without the other. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(7):1433–1438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ferrannini E. Hyperinsulinemia and Insulin Resistance. 2nd ed Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams, and Wilkins; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brown MS, Goldstein JL. The SREBP pathway: regulation of cholesterol metabolism by proteolysis of a membrane-bound transcription factor. Cell. 1997;89(3):331–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cagen LM, Deng X, Wilcox HG, et al. Insulin activates the rat sterol-regulatory-element-binding protein 1c (SREBP-1c) promoter through the combinatorial actions of SREBP, LXR, Sp-1 and NF-Y cis-acting elements. Biochem J. 2005;385(Pt 1):207–216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Deng X, Yellaturu C, Cagen L, et al. Expression of the rat sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c gene in response to insulin is mediated by increased transactivating capacity of specificity protein 1 (Sp1). J Biol Chem. 2007;282(24):17517–17529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Love DC, Hanover JA. The hexosamine signaling pathway: deciphering the “O-GlcNAc code”. Sci STKE. 2005;312:re13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Goldberg HJ, Whiteside CI, Hart GW, Fantus IG. Posttranslational, reversible O-glycosylation is stimulated by high glucose and mediates plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 gene expression and Sp1 transcriptional activity in glomerular mesangial cells. Endocrinology. 2006;147(1):222–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lu S, Archer MC. Sp1 coordinately regulates de novo lipogenesis and proliferation in cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2010;126(2):416–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Schiavoni G, Bennati AM, Castelli M, et al. Activation of TM7SF2 promoter by SREBP-2 depends on a new sterol regulatory element, a GC-box, and an inverted CCAAT-box. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1801(5):587–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sekar N, Veldhuis JD. Involvement of Sp1 and SREBP-1a in transcriptional activation of the LDL receptor gene by insulin and LH in cultured porcine granulosa-luteal cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004;287(1):E128–E135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sone H, Shimano H, Sakakura Y, et al. Acetyl-coenzyme A synthetase is a lipogenic enzyme controlled by SREBP-1 and energy status. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2002;282(1):E222–E230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lagor WR, de Groh ED, Ness GC. Diabetes alters the occupancy of the hepatic 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase promoter. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(44):36601–3668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Deng X, Cagen LM, Wilcox HG, et al. Regulation of the rat SREBP-1c promoter in primary rat hepatocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;290(1):256–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Repa JJ, Liang G, Ou J, et al. Regulation of mouse sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c gene (SREBP-1c) by oxysterol receptors, LXRα and LXRβ. Genes Dev. 2000;14(22):2819–2830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chung SS, Choi HH, Cho YM, Lee HK, Park KS. Sp1 mediates repression of the resistin gene by PPARγ agonists in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;348(1):253–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nelson BA, Robinson KA, Buse MG. High glucose and glucosamine induce insulin resistance via different mechanisms in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Diabetes. 2000;49(6):981–991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Duckworth WC, Hamel FG, Peavy DE. Two pathways for insulin metabolism in adipocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1358(2):163–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Brasse-Lagnel C, Fairand A, Lavoinne A, Husson A. Glutamine stimulates argininosuccinate synthetase gene expression through cytosolic O-glycosylation of Sp1 in Caco-2 cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(52):52504–52510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Majumdar G, Harrington A, Hungerford J, et al. Insulin dynamically regulates calmodulin gene expression by sequential o-glycosylation and phosphorylation of sp1 and its subcellular compartmentalization in liver cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(6):3642–3650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hayes BK, Hart GW. Protein O-GlcNAcylation: potential mechanisms for the regulation of protein function. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1998;435:85–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Reed BD, Charos AE, Szekely AM, Weissman SM, Snyder M. Genome-wide occupancy of SREBP1 and its partners NFY and SP1 reveals novel functional roles and combinatorial regulation of distinct classes of genes. PLoS Genet. 2008;4(7):e1000133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhang P, Klenk ES, Lazzaro MA, Williams LB, Considine RV. Hexosamines regulate leptin production in 3T3-L1 adipocytes through transcriptional mechanisms. Endocrinology. 2002;143(1):99–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zhang D, Ma J, Brismar K, Efendic S, Gu HF. A single nucleotide polymorphism alters the sequence of SP1 binding site in the adiponectin promoter region and is associated with diabetic nephropathy among type 1 diabetic patients in the Genetics of Kidneys in Diabetes Study. J Diabetes Complications. 2009;23(4):265–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Raghow R, Yellaturu C, Deng X, Park EA, Elam MB. SREBPs: the crossroads of physiological and pathological lipid homeostasis. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2008;19(2):65–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Anthonisen EH, Berven L, Holm S, et al. Nuclear receptor liver X receptor is O-GlcNAc-modified in response to glucose. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(3):1607–1615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Issad T, Kuo M. O-GlcNAc modification of transcription factors, glucose sensing and glucotoxicity. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2008;19(10):380–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chung SS, Kim JH, Park HS, et al. Activation of PPARγ negatively regulates O-GlcNAcylation of Sp1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;372(4):713–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lim K, Chang HI. O-GlcNAc inhibits interaction between Sp1 and sterol regulatory element binding protein 2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;393(2):314–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Roos MD, Su K, Baker JR, Kudlow JE. O glycosylation of an Sp1-derived peptide blocks known Sp1 protein interactions. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17(11):6472–6480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sealls W, Penque BA, Elmendorf JS. Evidence that chromium modulates cellular cholesterol homeostasis and ABCA1 functionality impaired by hyperinsulinemia–brief report. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31(5):1139–1140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Seo YK, Jeon TI, Chong HK, et al. Genome-wide localization of SREBP-2 in hepatic chromatin predicts a role in autophagy. Cell Metab. 2011;13(4):367–375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sleiman SF, Langley BC, Basso M, et al. Mithramycin is a gene-selective Sp1 inhibitor that identifies a biological intersection between cancer and neurodegeneration. J Neurosci. 2011;31(18):6858–6870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Chen G, Raman P, Bhonagiri P, et al. Protective effect of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate against cortical filamentous actin loss and insulin resistance induced by sustained exposure of 3T3-L1 adipocytes to insulin. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(38):39705–39709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. McClain DA, Hazel M, Parker G, Cooksey RC. Adipocytes with increased hexosamine flux exhibit insulin resistance, increased glucose uptake, and increased synthesis and storage of lipid. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;288(5):E973–E979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Thomson MJ, Williams MG, Frost SC. Development of insulin resistance in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(12):7759–7764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Inada S, Ikeda Y, Suehiro T, et al. Glucose enhances protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B gene transcription in hepatocytes. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2007;271(1–2):64–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Chung SS, Choi HH, Kim KW, et al. Regulation of human resistin gene expression in cell systems: an important role of stimulatory protein 1 interaction with a common promoter polymorphic site. Diabetologia. 2005;48(6):1150–1158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]