Abstract

Background and Objective: The guidelines of the German College of General Practitioners and Family Physicians (DEGAM) on frequent and important reasons for encounter in Primary Care play a central role in the teaching of Family Medicine. They were edited by the authors into an app for mobile phones, making them available at all times to General Practitioners and medical students. This study examines the issue: how useful do students consider this application within their learning process in Family Medicine?

Method: The short versions of the 15 DEGAM guidelines were processed as a web app (for all smartphone software systems) including offline utilisation, and offered to students in the Family Medicine course, during clinical attachments in General Practice, on elective compulsory courses or for their final year rotation in General Practice. The evaluation was made with a structured survey using the feedback function of the Moodle learning management system [http://www.elearning-allgemeinmedizin.de] with Likert scales and free-text comments.

Results: Feedback for evaluation came from 14 (25%) of the student testers from the Family Medicine course (9), the clinical attachment in General Practice (1), the final year rotation in General Practice (1) and elective compulsory courses (4). Students rated the app as an additional benefit to the printed/pdf-form. They use it frequently and successfully during waiting periods and before, during, or after lectures. In addition to general interest and a desire to become acquainted with the guidelines and to learn, the app is consulted with regard to general (theoretical) questions, rather than in connection with contact with patients. Interest in and knowledge of the guidelines is stimulated by the app, and on the whole the application can be said to be well suited to the needs of this user group.

Discussion: The students evaluated the guidelines app positively: as a modern way of familiarising them with the guidelines and expanding their knowledge, particularly through its use in waiting periods and the attractive medium smartphone. However, the latter prevents a mandatory curricular use in compulsory courses, since not all students use smartphones. It is a meaningful addition to existing teaching materials and supports evidence-based teaching in Family Medicine and is suitable for use not only in university course teaching but also during clinical training.

Keywords: Family medicine, General Practice, Primary Care, guidelines, medical training, mobile learning, app

Abstract

Hintergrund und Fragestellung: Die Leitlinien der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Allgemeinmedizin (DEGAM) zu häufigen und wichtigen Beratungsanlässen in der Hausarztpraxis sind ein zentraler Inhalt der Lehre im Fach Allgemeinmedizin. Durch die Autoren wurden sie als App für Mobiltelefone aufbereitet und stehen somit nun Hausärzten und Studierenden jederzeit zur Verfügung. Die vorliegende Studie untersucht die Fragestellung: Wie bewerten Studierende den Nutzen dieser Anwendung für ihren Lernprozess im Fach Allgemeinmedizin?

Methodik: Die Kurzversionen der 15 DEGAM-Leitlinien wurden als (Smartphone-Betriebssystem-unabhängige) Web-App mit Möglichkeit der Offline-Nutzung umgesetzt und Studierenden in Kurs, Blockpraktikum, Wahlfächern und PJ (Praktisches Jahr) Allgemeinmedizin angeboten. Die Evaluation erfolgte durch eine strukturierte Befragung über die Feedbackfunktion der Moodle-Lernplattform www.elearning-allgemeinmedizin.de mit Likertskalen und Freitextkommentaren.

Ergebnisse: Der Evaluations-Rücklauf kam von 14 (25%) der 56 studentischen TesterInnen aus dem Kurs Allgemeinmedizin (9), dem Blockpraktikum (1), dem PJ (1) und Wahlfächern (4). Die App selbst sehen die Studierenden als Mehrwert zur Print/PDF-Version. Sie nutzen sie häufig und erfolgreich in Nischenzeiten und vor/während/nach Lehrveranstaltungen. Neben allgemeinem Interesse / Kennenlernen der Leitlinien und Lernen wird sie zum Nachschlagen konkreter (theoretischer) Fragestellungen eingesetzt, weniger im Zusammenhang mit Patientenkontakten. Interesse und Kenntnis der Leitlinien wird durch die App gefördert, insgesamt ist die Anwendung für die Bedürfnisse dieser Usergruppe gut geeignet.

Diskussion: Die Leitlinien-App wurde von Studierenden sehr positiv bewertet: Als moderne Form, ihnen die Leitlinien näher zu bringen und ihre Kenntnisse zu erweitern, gerade auch durch den flexiblen Einsatz in Nischenzeiten und das attraktive Medium Smartphone. Letzteres verhindert aber auch eine verbindliche Curriculare Implementierung in der Pflichtlehre, da nicht alle Studierenden Smartphones nutzen. Sie ist eine sinnvolle Ergänzung mit Mehrwert zu den bereits bestehenden Lernangeboten und unterstützt die Evidenz basierte Lehre im Fach Allgemeinmedizin – die nicht nur für die universitären Kurse, sondern auch für Famulaturen geeignet ist.

Introduction

The guidelines of the German College of General Practitioners and Family Physicians (DEGAM) [1] target the most frequent and important reasons for encounter in Primary Care. They are also of central importance in the teaching of Family Medicine/General Practice. For this reason many universities incorporate the DEGAM guidelines into the syllabus, since they offer a concise summary of evidence-based, relevant and up to date information as well as recommendations on diagnostics and treatment. These recommendations are not based on final diagnoses but rather on symptoms (e.g. sore throat, coughing, ear ache).

The DEGAM guidelines, which are also freely available in the internet as pdf-documents, consist of the detailed long versions (50-290 pages in length), the two-page short versions and other material such as patient information and information for practice nurses etc. [http://www.degam-leitlinien.de].

The sheer volume of material makes it impracticable to carry the complete set of guidelines in printed form for use in theory or in practice. For this reason the authors processed the short versions of the 15 current Guidelines as an app for mobile phones, thus making them available at all times on the smartphones which, in most cases, are the constant companion of General Practitioners and students [1]. Simultaneously with the international release of the SIGN-app (Scottish Clinical Guidelines App [http://www.sign.ac.uk/guidelines/apps/index.html]) in April 2011, the DEGAM-app was placed free of charge at the disposal of under- and post-graduate testers at [http://www.elearning-allgemeinmedizin.de].

The teaching of Family Medicine/General Practice at university is done in different courses and clinical attachments (with slight variation at different universities): the Family Medicine course consists of lectures and seminars, whereby generally there is no direct contact with patients. In many universities the DEGAM-guidelines are taught explicitly during the Family Medicine course. In the latest modification of the Order Regulating Licencing to Practise Medicine [2] the clinical attachment in General Practice, which takes place with very few exceptions in a GP’s surgery, was set at a minimum of two weeks. Here, in a one-to-one teaching situation with a GP students gain a practical insight into the work of a General Practitioner, during which time the use of the DEGAM-guidelines often depends on the teacher. During the final year rotation in General Practice, which is also usually completed in a GP’s surgery or clinic, and which according to the latest modification of the Medical Licensure Act must be made available to an increasing number of medical students [2], the DEGAM-guidelines usually play an important role: firstly in the accompanying seminars and then in the concluding state examination. In various elective compulsory courses the guidelines may also play a greater or lesser role (e.g. “Online Course on General Practice Guidelines” or “Reasons for Encounter in General Practice”).

The emphasis of this publication lies on the description of the use of the DEGAM-guideline app by medical students during different stages of their studies of family medicine, and of its usefulness.

It has been shown internationally that the use of PDAs (Personal Digital Devices) by medical students has on the whole been well received and they seem to have some usefulness in the learning process, whereby the generally descriptive surveys provide no unequivocal supporting evidence [3]. The PDAs were superseded more and more by smartphones, which are now very common among medical students and doctors, with a clear upward trend [4], [5], [6]. Their use in training is also increasing: whereas they were formerly used mainly by senior medical students, they are now commonplace among students of all years [4], [5], [6]. In reviews of which apps are used in health care, those concerning diagnosis and treatment and for reference with regard to medication are the most popular among medical students, as well as, particularly during non-clinical semesters, apps concerning revision of learning matter [7], [4], [5], [6]. Nationally, and internationally, students want additional apps for learning and for reference, and for decision guidance in clinical situations [3], [8], [7], [4].

Apps already exist with the guidelines of German Medical associations / Colleges or with the German Disease Management Guidelines [e.g. https://www.aerzteblatt.de/archiv/128463/App-Leitlinien-Innere-Medizin], [5], but there does not appear to be an evaluation regarding the usefulness of the applications in undergraduate medical education.

This study is intended to provide a description of the use of a guideline app in medical training, of how the app is accepted and used by the students, of its benefits in the learning process and in dealing with guidelines. It also looks into which recommendations students have regarding improvements in the usefulness of the app and its use within undergraduate training in Family Medicine.

Objectives of this study

How do students judge the benefit of the DEGAM-guideline app for their learning process in the field of Family Medicine/General Practice? What suggestions do they have for its deployment in training / teaching?

Methods

DEGAM-guidelines as a smartphone application

For implementation the form “web-app” was chosen, which can be viewed (and downloaded into the cache) from the internet with the integrated browser of the mobile device and which can be used without an installation process. It is thus independent of the operating system and can be displayed on any smartphone or PC, and mostly can even be used in offline mode.

At present 15 guidelines can be reached directly from the start screen of the DEGAM guideline app (see Figure 1 (Fig. 1)). The short versions were copied word for word and, in order to make them legible on small smartphone displays, broken down into smaller units with headings which are directly accessible via a table of contents and which are linked with one another.

Figure 1. Screenshot start screen.

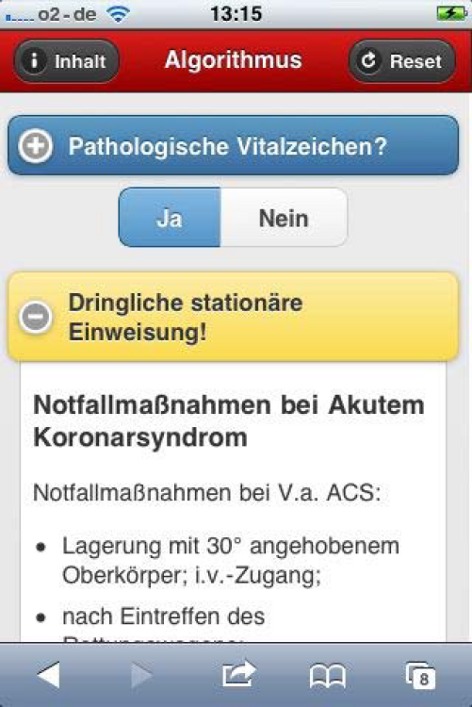

Depending on the contents of the guidelines (for instance nested charts) use was also made of collapsible submenus, zoomable diagrams, flow charts and interactive decision trees as well as static and dynamic algorithms (see Figure 2 (Fig. 2)).

Figure 2. Screenshot dynamic algorithm with collapsible submenus for guideline no. 15 – chest pain.

The first version of the app was released in April 2011 for use in undergraduate study and General Practice. The most recent (third) update was released on 1st March 2012.

Recruitment of test persons

Student testers

Students were told about the app during seminars and lectures of the Family Medicine course, as well as in the elective compulsory courses “Online Course on General Practice Guidelines” or “Reasons for Encounter in General Practice”. Additionally an email was sent out through the mailing lists of the other courses and attachments in Family Medicine on the learning platform of the University of Ulm. Final Year (PJ) students from different universities participating in the PJ-Platform Family Medicine [8] were invited to test the app and university lecturers at various universities were asked to inform their students.

Test-Users

All those who were interested in the app were able to register for it on the website [http://www.elearning-allgemeinmedizin.de] and they received free of charge access to the application. In return they were requested, after using the app for some weeks, to fill out an anonymous, structured feedback (the link to which was attached to the login data). There was no mandatory arrangement with sanctions for failing to provide the feedback. Three additional appeals / reminders for the evaluation were made by email (July 2011, April 2012, July 2012).

Feedback / Evaluation

Evaluation was done through the feedback function of the Moodle platform with Likert scales and free text comments, during which process the following data and information was collected:

demographic data (age, sex, student / doctor)

comments on the app (composition, layout, clarity)

when, where and how the app was used

interest in the guidelines and previous knowledge of them

suitability for one’s own requirements, positives, criticism and suggestions

suggestions for use in training

The questionnaire was compiled inductively on the basis of previous evaluations and adopted without alteration after testing by four students and two General Practitioners.

Results

Users, response rate and demographic data

89 students asked to be sent the access data for the app (registration).

56 students downloaded the app.

14 student evaluations were submitted (a response rate of 25%).

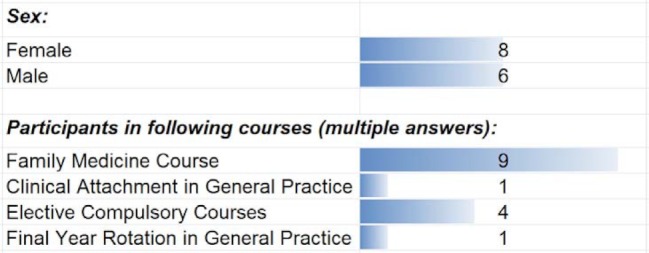

The demographic data of the student testers who filled out the evaluation is listed in table 1 (Tab. 1).

Table 1. demographic data of the 14 student testers.

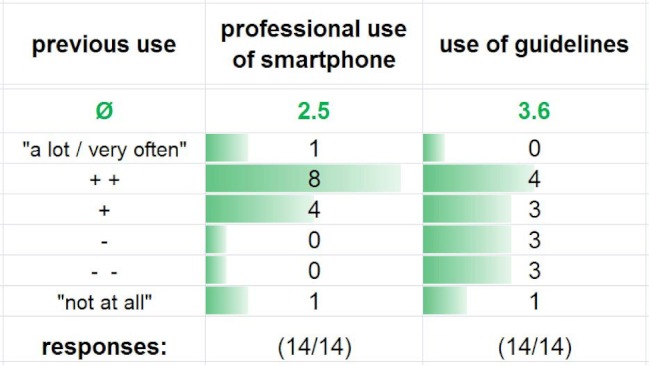

Previous use of smartphone and guidelines

A large proportion of students had already previously made regular use of a smartphone for “professional” purposes, i.e.: for academic studies. Use of the guidelines, on the other hand, was quite varied and clearly less frequent – see table 2 (Tab. 2).

Table 2. Previous use of smartphone and guidelines.

Download and design of the app

Response to the download, installation, clarity and design of the app is listed in table 3 (Tab. 3) – all aspects achieved a rating of between 1.4 and 2.0. Also listed is the assessment of the question of the additional benefit of the application in comparison with the printed or digital form of the short versions of the guidelines, and whether it were a useful addition, which was clearly confirmed.

Table 3. Feedback on the app itself.

- Download/installation (1 = “simple” – 6 = “only with greatest difficulty / considerable assistance needed”)

- Clarity (1 = “very clear layout” – 6 = “couldn’t navigate around it at all”)

- Design (1 = “excellent, very pleasing” – 6 = “I don’t like it at all”)

- Additional benefit of this application in comparison with the printed / digital form of the short versions of the guidelines? Useful addition? (1 = "definitely" – 6 = "not at all")

The responses with 6-point Likert scales correspond, with grading from 1 (“very good / very clear /…”) to 6 (“don’t like it / couldn’t use it / …”) approximately with the grading scheme in the German school system, and the computed average of the responses is therefore referred to as the “grade”.

Application scenarios

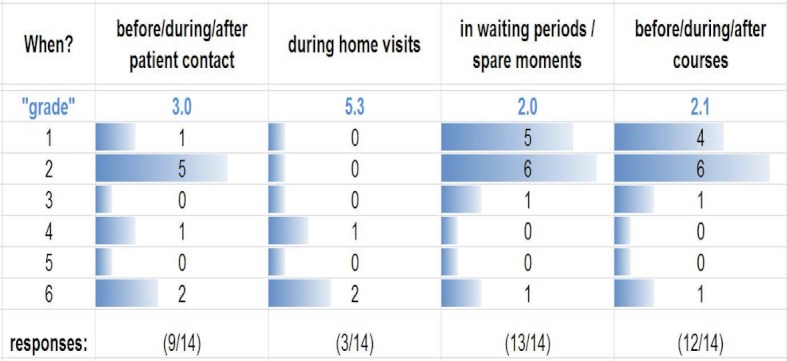

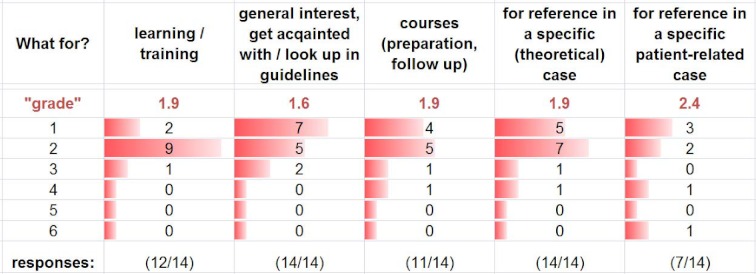

The usefulness / helpfulness of the application in various scenarios, as it was assessed by the testers, can be seen in table 4 (Tab. 4) and table 5 (Tab. 5):

Table 4. When was use made of the application, and was it helpful / useful?

(1 = „very helpful“ to 6 = „no advantage / usefulness“)

Table 5. For what was the application used and was it helpful in that situation?

(1 = “very helpful” to 6 = “unsuitable, of no value”)

„When“, i.e. in which situation the application was used, and whether it was considered to be helpful in that situation, is shown in table 4 (Tab. 4), whereby use in connection with patient contacts and particularly house calls was rarely specified (house calls 3 of 14 testers) and poorly graded, with 3.0 and 5.3. By contrast, use during waiting periods and in the context of lectures, frequently (12 and 13/14) and well graded, with 2.0 and 2.1.

The “what for” is listed in table 5 (Tab. 5), whereby use in learning and further training, general reference, specific theoretical issues and the preparation for and following-up of lectures was often specified and well graded (“grades 1.6 – 1.9”). Use in the context of specific patient-related issues was mentioned less frequently and was graded less well (7/14, “grade” 2.4).

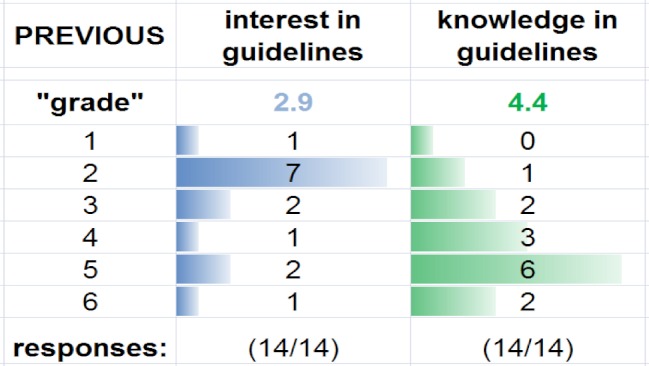

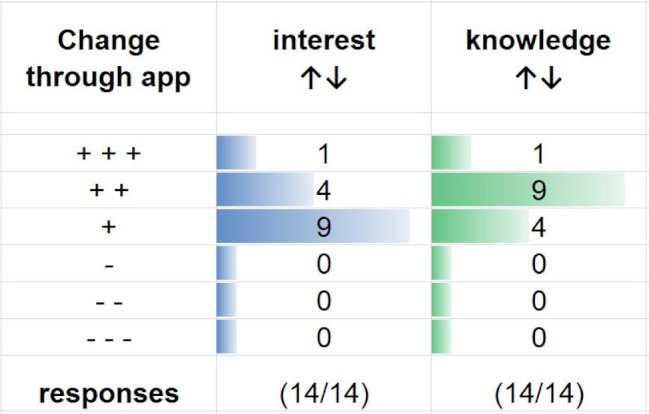

Interest in guidelines and knowledge of the guidelines

Students assessed their interest in guidelines as moderate (“grade” 2.9) before using the app and their knowledge of the guidelines as poor (“grade” 4.4) – see table 6 (Tab. 6). All of them experienced a positive change through the use of the app – see table 7 (Tab. 7).

Table 6. Previous interest in and knowledge of the guidelines.

- Interest (1 = "very great" to 6 = "no interest")

- Knowledge (1 = "very good" to 6 = "ultimately none")

Table 7. Changes through use of the app.

- Interest (1 = "my interest in guidelines is now much greater" to 6 = "my interest in guidelines has clearly decreased")

- Knowledge (1 = "I now know the guidelines much better" to 6 = "no help whatsoever, if anything I’m confused")

Overall assessment:

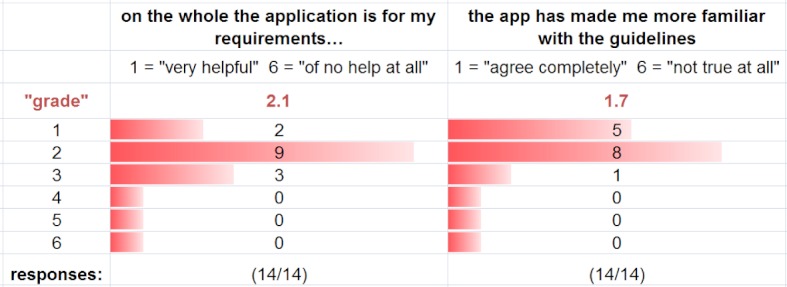

Finally the testers were asked to give an overall assessment of the application: on the whole the application is helpful in terms of the testers‘ requirements (“grade” 2.1, 14/14). It was capable of giving them a better understanding of the guidelines (“grade” 1.7., 14/14) – see table 8 (Tab. 8).

Table 8. Overall assessment of the application.

Free text answers

A number of questions were included which offered the possibility of giving a free text answer:

“I find the following aspects of the application positive:”

“I find the following aspects negative, the application should be improved in those areas:”

“What would you wish for in order to be able to make even more use of the application? How could the app be optimised for use in practice / in the learning process? Overall, do you have any suggestions?”

The answers and comments are given at the appropriate places within the discussion.

Discussion

Critical view on methods and limitations

A weak point of the survey is the very small number of responses, which could not be significantly increased even with three reminders per email. Its validity is thus reduced, but tendencies can nevertheless be observed. The small number of responses gives rise to a certain selectivity: the possibility is increased that interested persons (or ones who are particularly annoyed) respond. Since the application is currently a voluntary additional offer which is to be tested for possible uses, precisely these interested and critical persons were seen to be an interesting target group for this survey.

Two major problems which led to a large number of students not downloading the app despite being interested and having actively requested and received personal access data, was identified in an additional survey: the access to the app through an individual log-in on a platform, and the unfamiliar download route of the web-app, which differs greatly from the usual app-store process [9].

These barriers could be overcome through the development of a native app and free access without login, but in this case there would be financial (programming costs) and legal (copyright obligations) difficulties to resolve.

This survey is not a conclusive evaluation study, for which a larger number of responses would have been required, but it represents a feasibility study, a pilot survey in which emphasis is also placed on the qualitative description, namely the ways in which the app can be used by students, and a collection of ideas - which scenarios students themselves could imagine for its use in teaching. The evaluation has been therefore been made to a great extent qualitatively, in which case smaller numbers of responses may provide suggestions.

Target group and users

This application, in which the short versions of the DEGAM Guidelines were processed on a one-to-one basis for the small smartphone screen, is intended for the use of undergraduate medical students and doctors during and after completing specialist training, who are concerned with patient-centered care in the context of primary care (medical school, theory, practice).

Previous use of a smartphone in work / university environments was quoted as ranging from “not at all” to “very often”, whereby there were considerably more regular users than smartphone-newcomers. This corresponds with the study by Schulz et al. 2012 [7], which describes a high degree of smartphone usage among students of dentistry and medicine and the increasing wish of 89% of respondents for more e-learning offers. This high degree of smartphone usage and the demand of medical students for more apps for their learning process have also been shown internationally in the study by Payne et al. [8] and Mosa et al., that in particular young doctors and students made use of PDAs (Personal Digital Assistants), which are now increasingly being replaced by smartphones [4].

In the responses of the students, previous use of guidelines tended towards “to a lesser extent” (expressed as a simplified school grade – 1 being best and 6 the lowest grade – this was 3.6) and knowledge of the DEGAM Guidelines was said to be even poorer (“grade” 4.4) whereby a certain level of interest was said to exist (“grade” 2.9) – of course this had to be the case, otherwise the students would not have registered as testers and downloaded the app onto their smartphone.

Installation and feedback on the app

Download and installation of this (unfamiliar) web-app worked well and without any great problems among these in this smartphone experienced group, and clarity of arrangement and design were judged positively. The grades 1.6 and 2.0 take into account evaluations made of the first version of the app in April 2011, as a result of which (“more colour please”) improvements were made in colour and design for the 2nd and 3rd versions.

Use of the application

Situations in which students used the app were primarily “in waiting periods”, “while using public transport” etc., and “before/during/after lectures”. This corresponds with the theoretical considerations of Lemos et al., who propagate the idea of using waiting periods for learning, and the possibility of incorporating environmental information (situated learning) into their concept “How can m-learning (mobile learning) improve the quality of the teaching of medicine?” [10]. Mosa et al. also describe this usage of apps by medical students for learning and revision during spare moments in medical school, when no textbook is available. [4].

The application was judged to be helpful with regard to use in spare moments / waiting periods and in connection with lectures (“grades” 2.0 and 2.1). Deployment in these situations is also one of the reasons why all students attested the application a clear advantage over the printed and pdf-versions of the guidelines (“grade” 1.6).

„I’ve always got the guidelines with me and save a lot of paper. Perfect for quick reference.“

„Always with me, and otherwise I’d have to carry the print version around“

With regard to patient contact there were few and very varied responses, which can be explained by the lack of patient contact of the majority of responding students (only two had contact with patients: one in a clinical attachment and one in his final year rotation in General Practice).

This background is reflected again in the question of how the application was used: namely “general interest, learning about the guidelines and for reference reasons”, “to learn and expand my own knowledge”, “for a lecture (homework, preparation, follow-up)” and “consultation regarding a specific (theoretical) question”. It was also sometimes “consulted with regard to a specific patient-based question”, whereby the virtual patients of the “Online Course on General Practice Guidelines” were included. Helpfulness and usefulness of the app when used in the former ways were “graded” between 1.6 and 1.9, in specific patient-related questions the assessments ranged from 1 to 6 with few responses (“grade” 2.4).

(Two persons, both on courses not involving patient contact – gave an answer to each evaluation question, although they were explicitly asked to only provide a response to those questions which actually applied to them: both frequently evaluated items with a “6”; for instance “use during house visits” and “use before/during/after patient contact”. Obviously these negative evaluations really mean: “does not apply”. However, since from a purely scientific point of view the comments of all participants in the study have to be taken seriously, these negative assessments were not removed from the evaluation and were therefore incorporated into the “average grades”.)

Influence of the application on interest in, and knowledge of the, guidelines

After interest in, and knowledge of, the guidelines had been judged as being poor before use of the application (see above), an improvement was registered in both categories after using the application. This is reflected in free text comments:

“I think it’s a good thing that the guidelines are available as an app. It’s a very dry subject, so the combination with the smartphone is a perfect way to arouse interest”.

All in all the application had given the users a better understanding of the guidelines (“grade” 1.7) and it was considered to be “helpful to their requirements”. Since the guidelines are relevant to examinations, this positive assessment of the app by students is a strong argument for the integration of the application into the training.

Suggestions for use in medical training

The students named the practical sections of the training as being particularly suitable for use of the application:

“The application is very suitable for the Online Guidelines Course. I could also imagine it being useful in clinical attachment and during the final year”.

“Tip as a source of reference and for preparation for the clinical attachment in General Practice”

But it is also suitable for university courses:

“Used the app to prepare for lectures and courses …… good way of reminding oneself of the most important facts before a lecture.”

But they also saw the limitations in usage:

“I think a “compulsory” use in lectures or seminars would be problematical, because by no means all students have a smartphone, and compulsory use in team work would not be productive.”

In view of the alterations made in the Medical Licensure Act of 11.5.2012 with the introduction of a compulsory elective period in General Practice / Primary Care [2], the application also lends itself to use:

“The app would certainly come in very handy during an elective in General Practice.”

Positive comments on the application

The app itself was well received as an innovative application:

“I was pretty much taken with the DEGAM Guideline app. A move in the right direction at last, away from all those fusty old systems.”

“I‘ve always got the Guidelines with me and save a whole load of paper. Ideal for quick reference.”

And students even saw a benefit in using the application on PCs, although on the larger screen the pdf-versions of the short versions of the guidelines would have been easily legible, a benefit which extended to include tablets and iPads:

“For this [working on patient cases on a PC] using the application was very helpful, because it was not necessary to plough through all the individual guidelines. Everything was clearly laid out and well-arranged. The most important points are accentuated, which makes it quick and easy to find the right solutions.”

“The optical presentation of the information is very pleasing and one doesn’t get swamped with information as is the case with the “jam-packed” short versions of the guidelines.”

There was much praise for the design and the clarity of presentation:

“The optical presentation is very pleasing and information is easy to find and presented very clearly.”

(Even if this opinion was occasionally contradicted:

“I find the app in its present form relatively free of benefits, because it is totally confusing and badly structured”.)

Criticism and suggestions regarding the application

In the first versions “more colour” was demanded, which has already been implemented. The text-heaviness however, which was often a reason for complaint, stems from the original (the short versions of the guidelines were adopted word for word, the only illustrations being flow-charts). The interactive algorithms which were requested are also dependent on the originals and could successfully be incorporated into the most recent guideline “chest pain”.

Until now it has been mainly General Practitioners, who regularly use the guidelines, who have requested the addition of the long versions of the guidelines, although students have also expressed the same wish:

„Apart from that it would be nice if patient information, long versions and other additional pieces of information, which are so far only available via a link from the web-app, could be saved for offline use“.

The wish for the addition of a search function was also expressed several times:

“A search function would be good to help find things faster”

Simplified access for students and reliable offline use could be achieved by placing native apps in app-stores.

Outlook

The implementation of many of the students’ suggestions is already being considered:

The creation of native apps (iOS, Android), possibly also hybrid-apps for other operating systems

The inclusion of the long versions, patient information and other material

The addition of a search function and a bookmark function

The app is an appropriate additional tool for medical students and for training in Family Medicine and access to it will at some point be simplified in order to make it available to all students during their studies and in the further course of their career.

Abbreviated conclussion

Guideline app

Well received by those who have used it (and who have sent feedback)

Good and modern medium which can be used to awaken interest in the guidelines and improve knowledge of them

Well-arranged and always available, suited to the needs of students

Use in training

Use in “waiting periods / spare moments”, during lectures and generally in the revision of knowledge, and as a source of reference in theoretical and practical questions

Only as a supplementary offer, because not all students possess a smartphone – although use on PCs was seen as beneficial in comparison to the PDFs, because of the clear arrangement of the contents.

A meaningful addition to the existing offers on revision and learning: supports evidence based teaching in Family Medicine

Interest in and knowledge of the guidelines are stimulated by the app

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Waldmann UM, Weckbecker K. DEGAM-Leitlinien als App für Mobiltelefone – Einsatz in der hausärztlichen Praxis und erstes Feedback. 45. Kongress für Allgemeinmedizin und Familienmedizin, Forum Medizin 21; 22.-24.09.2011; Salzburg. 2011. p. Doc11fom012. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.3205/11fom012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bundesrat. Artikel 3 Weitere Änderung der Approbationsordnung für Ärzte zum 1. Oktober 2013. Bundesrat Drucksache. 2012;238(12):18. Available from: http://www.bundesrat.de/cln_110/SharedDocs/Drucksachen/2012/0201-300/238-12,templateId=raw,property=publicationFile.pdf/238-12.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindquist AM, Johansson PE, Petersson GI, Saveman BI, Nilsson GC. The use of the personal digital assistant (PDA) among personnel and students in health care: a review. J Med Internet Res. 2008;10(4):e31. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1038. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.2196/jmir.1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mosa ASB, Yoo I, Sheets L. A Systematic Review of Healthcare Applications for Smartphones. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2012:12(1). doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-12-67. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1472-6947-12-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ollenschläger, G Nationale VersorgungsLeitlinien (NVL) jetzt auch als App. Z Evidenz Fortbild Qual Gesundheitswes. 2012;106(9):619. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waldmann UM, Gulich M, Weckbecker K, Böhme K. Allgemeinmedizin auf der PJ-Plattform des Netzwerks ELearning Allgemeinmedizin" (ELA): Universitätsübergreifende Online-Seminare für Studierende im Praktischen Jahr – Bewertung und Motivation von Studierenden und Dozenten. Jahrestagung der Gesellschaft für Medizinische Ausbildung (GMA); 05.-08.10.2011; München. 2011. p. Doc11gma157. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.3205/11gma157. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schulz P, Sagheb K, Affeld H, Kumar, Taylor K, Walter C. Akzeptanz und Nutzung von portablen Internet Geräten (Tablet PC, Smartphones) in der zahnmedizinischen und medizinischen Ausbildung. Jahrestagung der Gesellschaft für Medizinische Ausbildung (GMA); 27.-29.09.2012; Aachen. 2012. p. DocP228. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.3205/12gma130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Payne KFB, Wharrad H, Watts K. Smartphone and medical related App use among medical students and junior doctors in the United Kingdom (UK): a regional survey. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2012;12:121. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-12-121. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1472-6947-12-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waldmann UM, Schmidt UM, Weckbecker K. DEGAM-Leitlinien als "App" für Mobiltelefone – Umsetzung und Rückmeldung der Tester. GMS Med Inform Biom Epidemiol. :[in Begutachtung]. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lemos M, Biermann H, Sopka S, Beckers S, Ohnesorge-Radtke U. Mobiles Lernen in der Medizin: neue Wege zum Erlernen praktischer Fähigkeiten an der Medizinischen Fakultät der RWTH Aachen – ein Konzept. Jahrestagung der Gesellschaft für Medizinische Ausbildung (GMA); 05.-08.10.2011; München. 2011. p. Doc11gma164. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.3205/11gma164. [DOI] [Google Scholar]