Abstract

Background

The 15-Objects Test (15-OT) provides useful gradation of visuoperceptual impairment from normal aging through Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and correlates with temporo-parietal perfusion.

Objectives

To analyse progression of 15-OT performance in Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) and AD, and its correlates with cognition and Single Photon Emission Computerized Tomography (SPECT). Further, to examine neuropsychological and SPECT differences between the MCI patients who developed AD and those who didn’t.

Methods

From the initial 126 participants (42/group), 38AD, 39MCI and 38 elderly controls (EC) were reassessed (SPECT: 35AD, 33MCI, 35EC) after two years. The progression of cognitive and SPECT scores during this period was compared between groups, and baseline data between converters and non-converters. SPECT data were analysed by SPM5.

Results

The 15-OT was the only measure of progression that differed between the three groups; worsening scores on 15-OT were associated with worsening in verbal and visual retention, and decreased perfusion on left postsubicular area. In the MCI patients cerebral perfusion fell over the two years in medial-posterior cingulate and fronto-temporo-parietal regions; AD showed extensive changes involving almost all cerebral regions. No SPECT changes were detected in controls. At baseline, the MCI patients who developed AD differed from non-converters in verbal recognition memory, but not in SPECT perfusion.

Conclusion

SPECT and 15-OT appear to provide a potential measure to differenciate between progression of normal aging, MCI and AD. Worsening on 15-OT was related to decreased perfusion in postsubicular area; but further longitudinal studies are needed to determine the contribution of 15-OT as a predictor of AD from MCI.

Keywords: Visuoperception, The 15-Objects test, cerebral perfusion, brain SPECT, two-year follow-up, prospective, longitudinal, Mild Cognitive Impairment, Alzheimer’s disease

INTRODUCTION

The detection of the earliest cognitive changes of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a matter of great clinical interest. Neuropsychological studies have found that in addition to episodic memory impairment [1,2,3], patients with the amnestic form of Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) frequently show impairment on other cognitive functions such as attention [4,5,6], semantic memory [3,7], executive functions [3,8], visuoperception [9,10,11] and visuospatial ability [12]. Individuals with amnestic MCI with multiple cognitive domain affected have a greater risk of conversion to AD dementia than those individuals with MCI with an isolated memory impairment [13,14,15,16,17]. Thus, the use of cognitive tests sensitive to cognitive dysfunction in addition to memory will increase the sensitivity of a clinical examination to detect the prodromal stage of AD.

In addition, clinical follow-up of patients by the neuropsychologist is crucial in order to determine whether poor performance at the initial evaluation represented the earliest signs of an impending dementia, or was simply an incidental finding or a normal variant. Therefore, it is important to determine which variations in test scores are characteristic of normal aging and which are more characteristic of MCI, especially MCI that will progress to dementia. Cognitive test performance declines significantly faster in MCI patients than it does in normal subjects, especially in terms of episodic memory [7, 13], semantic memory [7] and perceptual speed [7]. However, there are no previous reports about changes on visuoperceptive tests or, more specifically, the 15-Objects Test (15-OT).

Tests of episodic memory and executive function (e.g., Trail Making B) are as accurate in predicting the development of AD from MCI as are volumetric MRI measures (i.e., entorhinal cortex, hippocampus) [18,19,20,21] and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers [21]. Although biomarkers are now recommended for use in diagnosis [22], MRI and CSF methodologies, for example, are costly and have some disadvantages (i.e., claustrophobia, patients having pacemakers; infection). By contrast, neuropsychological assessment is cost-effective, and is usually the only measure of brain function used in the diagnostic process.

Visual object recognition deficits are an early sign of AD, and they can be detected in even in amnestic MCI [9,10,11,12] and mild AD patients [23,24,25]. These visuoperceptual deficits worsen with disease progression in AD patients [26], and they are related to CNS perfusion abnormalities in the posterior cingulate, occipital and inferior temporal cortices [11, 27, 28], and the right temporal pole [11]. However, the progression of visuoperceptual impairment, and its association with changes in brain perfusion and other cognitive processes, have not been previously reported in MCI.

We report here the results of the 2-year follow-up of our previous study demonstrating that the 15-OT is sensitive to the clinical stages of the visuoperceptual impairment in AD, and provides a useful gradation of impairment from normal aging to AD [10,11]. However, to demonstrate that the 15-OT is useful in early detection of AD, it is also important to demonstrate that the performance declines in MCI and AD patients. Indeed, we would expect this to be the case, as we have found that performance on the 15-OT is related to perfusion in the posterior cingulate and right temporal cortices [11], which are decreased in AD (and, hence more pathology in these regions over time should result in poorer performance).

The purpose of the present study was to analyse the progression of performance on the 15-OT in MCI and AD patients, and to test the hypothesis that there will be a decline in accuracy linked to changes in regional cerebral perfusion. A secondary objective was to identify neuropsychological and SPECT patterns that can differentiate those MCI patients who develop AD from those who do not.

METHODS

Subjects

From the original sample of 126 participants (42 per group) [11], 38 AD (90%), 39 amnestic MCI (30 multiple domain and 9 single domain) (93%) and 38 elderly controls (EC) (90%) were reassessed with neurological and neuropsychological examinations 2 years after study entry. Within three weeks of the clinical assessment, a SPECT scan of the brain was performed in 35 AD (92%), 33 amnestic MCI (85%) and 35 EC (92%). Eleven subjects were not reassessed: 2 participants refused to continue, 3 suffered health complications, 3 patients died, and 3 were institutionalized in a geriatric residence. At one-year follow-up, 120 of the participants received a neurological and neuropsychological assessment, but they did not undergo the SPECT scan (see Table 1). The APOE status of 107 participants (35 AD, 37 MCI and 35 EC) was determined. Demographic, clinical and genetic characteristics of the subjects who continued in the study are detailed in Table 1 of supplemental material. They did not differ in either clinical or cognitive measures from those who did not.

Table 1.

Participants flow through study.

|

The study inclusion and exclusion criteria were detailed elsewhere [11]. Briefly, the AD patients all met the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke-Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS/ADRDA) criteria for Probable AD, with a Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) score of 1, and they were all taking acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChEIs).

The MCI patients fulfilled Petersen’s criteria for amnestic MCI, with a CDR rating of 0.5. None were taking any dementia medication (i.e., AChEIs or memantine) at study entry, but in case of conversion to dementia, AChEIs were introduced.

The control subjects were volunteers who had no neurological or psychiatric symptoms, no evidence (by history) of functional impairment due to declining cognition, and who had normal performance on the neuropsychological battery.

The study exclusion criteria for all participants were: age younger than 65 years, illiteracy, presence of moderate depressive symptoms or a DSM-IV Axis-I psychiatric disorder (except for dementia), neurological disease (other than dementia), structural focal lesion on CT imaging, history of alcohol or other substance abuse, important visual abnormalities including glaucoma or cataracts, or severe aphasia.

Neuropsychological assessment

The participants were administered the 15-OT and a neuropsychological battery at all study visits. The neuropsychological battery [11] included measures sensitive to orientation, attention, verbal and visual memory, language, visual gnosis, praxis and executive functions. The tests were: Temporal, Spatial and Personal Orientation; Digit span forwards and backwards, Block Design and Similarities subtests of Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Third Edition (WAIS-III); The Word List Learning test from the Wechsler Memory Scale-Third Edition (WMS-III); the RBANS visual memory subtest; Verbal comprehension (2 simple, 2 semi-complex and 2 complex commands); an abbreviated 15 item confrontation naming test from the Boston Naming Test; the Poppelreuter test; Luria’s Clock test; Ideomotor and Imitation praxis; the Automatic Inhibition subtest of the Syndrom Kurtz Test (SKT); Phonetic Verbal Fluency (words beginning with ‘P’ during one minute); Semantic Verbal Fluency (‘animals’ during one minute), and the Spanish version of the Clock Test.

Brain SPECT procedure

Within three weeks of baseline and 2-year assessments, a brain SPECT was performed. The brain SPECT procedure was described previously [11].

Statistical analysis

Clinical and Neuropsychological Variables

Statistical analysis of the clinical variables was performed using SPSS (version 18.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, Ill). An ANOVA with post-hoc comparisons (Bonferroni) were used to compare sociodemographic, clinical and neuropsychological data between the three groups at each visit. Linear Mixed Models were used to compare the progression of performance on the 15-OT and other neuropsychological tests between baseline and 1-year and 2-year follow-ups, and between groups. That is, the progression of performance on the neuropsychological tests between baseline and 2-year follow-up was compared between groups. The principal effects were executed fixing every group (EC, MCI and AD) and contrasting each point with the next higher one.

In the whole group, the percentage of change on the 15-OT (( 2-year follow-up 15-OT score - baseline 15-OT score)/baseline 15-OT score)) × 100), was correlated with the percentage of change on other cognitive tests (11 variables), using Bonferroni’s correction (p= 0.004). The percentage 15-OT variable was regressed on the variables that had significant unadjusted associations in the correlation analysis, using forward, stepwise entry.

Finally, non-parametric Mann-Whitney U-tests were performed between the baseline neuropsychological scores of those MCI subjects who developed AD and those who did not. Adjusted effect sizes for those parameters that were associated with conversion were calculated with unconditional binary logistic regressions, using age, gender, educational level and APOE genotype as covariates.

Image Voxel-Based Analysis of Perfusion (VBA)

A voxel-level analysis of the SPECT data was performed on the non-attenuation corrected studies running in Matlab 7.2 (Mathworks Inc, Sherborn, MA). The raw images were converted from DICOM to Analyze format using MRIcro (http://www.cabiatl.com/mricro/), and transferred to SPM5.

The images were deformed into the standard space of the Montreal Neurological Institute atlas and spatially re-smoothed with a 3D Gaussian kernel with 8-mm FWHM. Paired t-tests and appropriate linear contrasts were used to compare SPECT images from each of the patient groups on a voxel-by-voxel basis, generating statistical parametric maps of group-related differences in regional-whole brain perfusion. Significance levels were adjusted for a false discovery rate (p< 0.05) [29].

In order to examine the association between the 15-OT and cerebral perfusion reductions in the whole sample (including EC, MCI and AD groups), a parametric image of the perfusion changes was computed. To do that, the baseline and follow-up scans were intensity-normalized to maximum, and the difference between the images (T1–T2) was calculated at the voxel level. The resulting parametric images (baseline – 2-year follow-up difference) were correlated with changes on 15-OT within SPM5, using a simple correlation test. Results meeting a height threshold of p= 0.001 (uncorrected) and k= 100 were considered statistically significant. Differences in cerebral perfusion between the MCI patients who developed AD and those who did not were assessed using a two-factor ANOVA (time × group).

RESULTS

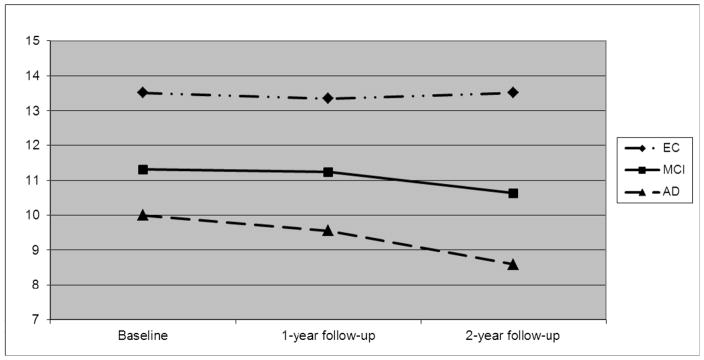

The scores of the participants on the neuropsychological tests at baseline and at the 1-year and 2-year follow-ups are detailed in Table 2. The 15-OT performance was significantly different between groups at each visit. That is, at baseline, at 1-year follow-up and at 2-year follow-up, scores of MCI and AD patients were significantly lower than those of controls, and the MCI subjects performed significantly better than the AD patients (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison between progression of neuropsychological performances from baseline to 2-year follow-up between groups.

| EC | MCI | AD | F (2, 125) | EC-AD | MCI-AD | EC-MCI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X̄ (S.E.) | X̄ (S.E.) | X̄ (S.E.) | |||||

| Baseline 1-year 2-year | Baseline 1-year 2-year | Baseline 1-year 2-year | |||||

| 15-OT answers | 13.6 (0.3) 13.4 (0.4) 13.9 (0.4) | 11.3 (0.4) 11.4 (0.4) 10.6 (0.4) | 9.9 (0.3) 9.4 (0.4) 8.4 (0.4) | 5.339*** | *** | ** | * |

| 15-OT errors | 1.4 (0.2) 1.4 (0.3) 1.2 (0.3) | 3.1 (0.3) 3.0 (0.4) 3.0 (0.3) | 4.1 (0.2) 3.6 (0.3) 3.0 (0.3) | 1.661 | |||

| Orientation | |||||||

| Temporal | 4.9 (0.2) 4.8 (0.2) 4.9 (0.2) | 3.9 (0.2) 4.0 (0.2) 3.8 (0.2) | 2.4 (0.2) 2.0 (0.2) 1.4 (0.2) | 4.359** | *** | ** | |

| Memory | |||||||

| Learning WMS-III | 31.2 (0.9) 32.1 (0.7) 30.2 (0.8) | 19.1 (1.0) 19.4 (0.9) 19.1 (1.0) | 15.2 (0.9) 13.9 (0.7) 11.3 (0.8) | 3.163* | ** | ||

| Retention WMS-III | 8.4 (0.3) 8.2 (0.3) 7.9 (0.3) | 1.6 (0.3) 1.4 (0.3) 1.4 (0.3) | 0.2 (0.3) 0.1 (0.3) 0.1 (0.3) | 0.255 | |||

| Recognition WMS-III | 11.3 (0.4) 11.4 (0.4) 11.6 (0.4) | 9.9 (0.5) 9.7 (0.4) 9.4 (0.5) | 6.3 (0.4) 6.7 (0.4) 6.3 (0.4) | 0.840 | |||

| Retention RBANS | 7.9 (0.3) 8.2 (0.3) 8.3 (0.3) | 3.9 (0.4) 3.7 (0.3) 3.6 (0.4) | 1.3 (0.3) 1.0 (0.3) 0.8 (0.3) | 1.827 | |||

| Recognition RBANS | 9.2 (0.3) 9.3 (0.3) 9.5 (0.4) | 6.7 (0.4) 7.0 (0.4) 6.4 (0.4) | 5.4 (0.3) 5.9 (0.3) 5.6 (0.4) | 0.513 | |||

| Digit span Forward | 8.0 (0.3) 8.4 (0.3) 7.8 (0.3) | 7.5 (0.4) 7.6 (0.4) 7.7 (0.4) | 6.9 (0.3) 6.4 (0.3) 6.5 (0.3) | 2.044 | |||

| Digit span Backward | 5.2 (3.6) 5.2 (3.4) 5.0 (3.5) | 4.2 (0.3) 4.2 (0.3) 4.3 (0.4) | 3.7 (0.3) 3.5 (0.3) 3.5 (0.3) | 0.248 | |||

| Praxis | |||||||

| Ideomotor | 4.0 (0.3) 4.0 (0.3) 4.0 (0.4) | 4.0 (0.0) 4.0 (0.0) 4.0 (0.1) | 3.9 (0.0) 3.9 (0.0) 3.8 (0.0) | 1.270 | |||

| Construction | 4.0 (0.2) 3.9 (0.2) 3.9 (0.2) | 3.1 (0.2) 3.3 (0.2) 3.0 (0.2) | 2.7 (0.2) 2.4 (0.2) 2.0 (0.2) | 2.945* | ** | ||

| Imitation | 3.9 (0.1) 3.9 (0.1) 3.9 (0.2) | 3.4 (0.2) 3.2 (0.2) 2.9 (0.2) | 2.3 (0.1) 2.4 (0.1) 2.1 (0.1) | 1.365 | |||

| Language | |||||||

| Comprehension | 6.0 (0.1) 6.0 (0.1) 5.9 (0.1) | 5.8 (0.1) 5.7 (0.1) 5.8 (0.1) | 5.6 (0.1) 5.6 (0.1) 5.5 (0.1) | 0.706 | |||

| Repetition | 4.0 (0.0) 3.9 (0.1) 4.0 (0.0) | 4.0 (0.0) 4.0 (0.1) 4.0 (0.0) | 4.0 (0.0) 3.9 (0.1) 3.9 (0.0) | 1.064 | |||

| 15-item BNT | 14.9 (0.3) 14.8 (0.3) 14.9 (0.4) | 13.2 (0.4) 13.3 (0.4) 12.5 (0.4) | 12.4 (0.3) 12.4 (0.3) 10.9 (0.4) | 4.302** | *** | *** | |

| Visuoperception | |||||||

| Poppelreuter test | 9.9 (0.2) 9.8 (0.2) 10.0 (0.2) | 9.1 (0.2) 9.2 (0.3) 9.0 (0.3) | 8.7 (0.2) 8.8 (0.2) 8.0 (0.2) | 3.207* | ** | *** | |

| Luria’s Clock test | 3.7 (0.1) 3.6 (0.2) 3.5 (0.2) | 2.7 (0.2) 3.1 (0.2) 2.9 (0.2) | 2.2 (0.1) 2.1 (0.2) 1.7 (0.2) | 2.081 | |||

| Executive functions | |||||||

| SKT seconds | 27.7 (1.8) 27.4 (2.0) 29.2 (2.7) | 32.3 (2.1) 31.8 (2.3) 33.8 (3.2) | 39.6 (1.8) 39.9 (2.0)48.6 (2.7) | 1.892 | |||

| SKT errors | 0.4 (0.7) 0.6 (0.7) 0.8 (0.9) | 1.8 (0.8) 2.5 (0.8) 1.7 (1.1) | 4.2 (0.7) 4.5 (0.7) 6.9 (0.9) | 2.473* | * | * | |

| Phonetic VF | 14.8 (0.8) 14.0 (0.8) 13.6 (0.7) | 11.0 (0.9) 12.1 (1.0) 10.8 (0.9) | 11.7 (0.8) 11.5 (0.9) 8.7 (0.7) | 3.981** | * | ** | |

| Semantic VF | 18.4 (0.8) 18.6 (0.8) 18.1 (0.8) | 12.1 (0.9) 11.9 (0.9) 11.4 (0.9) | 11.2 (0.8) 10.3 (0.8) 8.1 (0.7) | 3.531** | *** | * | |

| Abstract Reasoning | 11.7 (0.4) 11.6 (0.4) 11.9 (0.4) | 9.4 (0.4) 9.1 (0.4) 8.6 (0.5) | 8.5 (0.4) 8.6 (0.4) 7.7 (0.4) | 1.833 | |||

| Global cognition | |||||||

| MMSE | 29.35(0.3) 29.03(0.4) 28.52 (0.5) | 26.25(0.4)26.05(0.4)25.38(0.6) | 23.21(0.3)22.01(0.4)20.04(0.5) | 4.431** | *** | * | |

| Clock Test | 6.9 (0.3) 6.8 (0.3) 6.8 (0.3) | 5.5 (0.3) 5.3 (0.3) 5.4 (0.4) | 4.9 (0.3) 4.4 (0.3) 3.8 (0.3) | 2.716* | ** | ||

p<0.05,

p≤0.01,

p≤0.001

It was practically a constant and it cannot be calculated.

EC: Elderly Controls; MCI: Mild Cognitive Impairment; AD: Alzheimer’s disease. 15-OT: The 15-Objects test; S.E.: Standard error; WMS-III: Wechsler Memory Scale-III; 15-item BNT: 15 items abreviated Boston Naming Test; SKT: Automatic Inhibition subtest of the Syndrom Kurtz Test (number of errors); VF: verbal fluency; MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination.

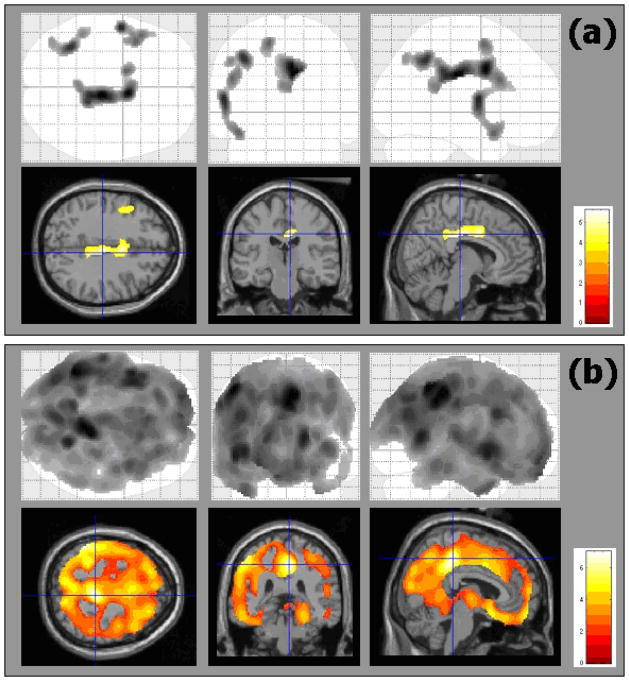

The analysis of progression on the neuropsychological tests performances from baseline to 2-year follow-up showed that MCI declined significantly faster than controls only on the 15-OT. The AD patients declined significantly faster than both the MCI and EC subjects on the 15-OT (see Table 2 and Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Scores on the 15-OT at baseline and one-year and two-year follow-ups.

The percent change between baseline and 2-year follow-up in the 15-OT was significantly correlated with the percent change in verbal learning (r=0.36, p<0.0005), verbal long-term memory (r=0.47, p<0.0005), visual long-term memory (r=0.43, p<0.0005), Poppelreuter test (r=0.21, p=0.021), automatic inhibition (SKT time) (r=0.19, p=0.043), confrontational naming (r=0.37, p<0.0005) and phonetic verbal fluency (r=0.44, p<0.0005). However, the correlations with Poppelreuter and SKT tests did not reach statistical significance after Bonferroni’s correction. In the adjusted model, only verbal (WMS-III list) and visual (RBANS) long-term memory performance changes were statistically associated with the 15-OT change. These two variables explained 29% of the observed variance of change on the 15-OT performances.

With regard to SPECT scans, the EC group did not show statistically significant changes in cerebral perfusion between baseline and 2-year follow-up. In the MCI group, the perfusion levels fell between baseline and 2-year follow-up in small areas located in middle and posterior cingulated (bilaterally), and left frontal, temporal and parietal regions. In contrast to the MCI group, the AD patients showed extensive changes in all cerebral lobes, mainly in the posterior cingulate (see Table 3 and Figure 2 for details).

Table 3.

Brain areas showing changes between baseline and 2-year follow-up in EC, MCI and AD groups.

| Group | Region | Cluster size (num. voxels) | Coordinates (X Y Z) | Z scores of maximum | p (FDR) cluster | p (FDR) voxel |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC | No significant changes | |||||

| MCI | Bilateral Middle and Posterior Cingulate, Left Frontal Lobe (Supplementary Motor Area) | 1188 | 8 −22 34 | 4.59 | <0.001 | 0.028 |

| Left Frontal Lobe (precentral and rolandic), Left Temporal Pole, Left Parietal Lobe (Postcentral gyrus) | 722 | −56 −4 12 | 4.30 | 0.003 | 0.028 | |

| Left Parietal Lobe and Angular Gyrus. | 444 | −38 −50 46 | 4.24 | 0.023 | 0.028 | |

| AD | Bilateral Middle and Posterior Cingulate, Bilateral Temporal Lobe, Bilateral Supramarginalis, Bilateral Insula, Bilateral Parietal Lobe (Cuneus, Precuneus and Postcentral gyrus), Bilateral Frontal Lobe (Precentral gyrus, Motor area), Left Occipital Lobe. | 78328 | 2 −40 40 | 5.54 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

EC: Elderly Controls; MCI: Mild Cognitive Impairment; AD: Alzheimer’s disease.

Figure 2.

Regional changes in brain perfusion between baseline and 2-year follow-up in MCI (a) and AD (b) groups.

The top row is the SPM5 “glass image” showing all significant voxels in axial, coronal and saggital views, respectively. The bottom row shows the significant voxels projected onto the MNI template, focusing on peak values in the cingulate gyrus.

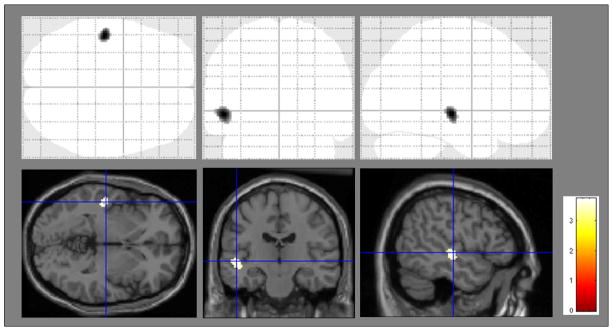

In the whole sample, the decline in performance on the 15-OT between baseline and 2-year follow-up was significantly correlated (p= 0.001) with cerebral perfusion reduction in the left Broadman Area (BA) 48 (or retrosubicular) (see Figure 3). However, the correlation analyses in the separated groups did not achieve statistical significance.

Figure 3.

Regions showing statistically significant correlation between cerebral perfusion change and change in performance on the 15-OT in all study subjects. The significant area (X, Y, Z) is located in Brodman’s Area 48 (left).

From the initial 42 MCI patients, 6 (15.4%) out of 39 MCI subjects developed AD dementia after 1 year, 32 (82%) mantained stable and 1 (2.6%) normalized. After 2 years an additional 9 MCI patients developed dementia for total of 15/40 (37.5%). Of these, 14 developed AD and 1 a fronto-temporal dementia. Moreover, an additional MCI patient normalized performance or improved clinical state for a two year total of 2/40 (5%). The conversion rate of MCI to AD was 15.4% at 1-year follow-up and 35% at two-year follow-up, with a mean annual conversion rate of MCI to AD of 19%. From the initial 42 EC subjects, 3 out of 38 (7.9%) had converted to non-amnestic MCI (secondary to vascular pathology in two cases and depression in one case), but none of them converted to dementia.

The MCI subjects who developed AD differed from non-converters MCI on the verbal recognition subtest of the WMS-III Word List Learning test (p= 0.002). Although RBANS visual retention score differed between groups, it did not reach significance after Bonferroni’s correction (p≤ 0.002). The WMS-III verbal recognition effect remained after multivariate logistic regression adjusting for age, gender, education and APOE status (Odds Ratio = 0.483, 95% Confidence Interval = [0.279–0.837], p= 0.010).

The baseline score on the 15-OT and Poppelreuter test scores did not differ between the MCI converters and non-converters (see Table 4). Further, there were no statistically significant differences in cerebral perfusion between the MCI converters and non-converters.

Table 4.

Comparison between those MCI who developed AD and those who maintained stable.

| Converters to AD | Non converters to AD | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| X̄ (SD) | X̄ (SD) | ||

| N (male, female) | 14 (4, 10) | 23 (7, 16) | |

| Age | 77.9 (3.8) | 76.3 (4.4) | 0.344 |

| 15-OT answers | 11.5 (2.1) | 11.1 (2.0) | 0.467 |

| 15-OT errors | 2.9 (2.1) | 3.3 (1.7) | 0.467 |

| Orientation | |||

| Temporal | 3.6 (1.6) | 3.9 (1.0) | 0.988 |

| Spatial | 5.0 (0.0) | 4.9 (0.3) | 0.676 |

| Personal | 4.7 (0.5) | 5.0 (0.2) | 0.231 |

| Memory | |||

| Total Learning WMS-III | 18.4 (5.2) | 19.3 (5.0) | 0.526 |

| Delayed Recall WMS-III | 0.7 (1.0) | 1.6 (1.6) | 0.122 |

| Recognition WMS-III | 7.2 (3.0) | 9.8 (2.4) | 0.002* |

| Visual mem. R-BANS | 1.7 (1.7) | 3.6 (2.2) | 0.017 |

| Visual recog. R-BANS | 6.5 (1.9) | 6.5 (2.2) | 0.865 |

| Digit span Forward | 4.8 (0.8) | 5.1 (1.3) | 0.567 |

| Digit span Backward | 3.4 (0.7) | 3.4 (0.9) | 0.841 |

| Praxis | |||

| Ideomotor | 3.9 (0.3) | 4.0 (0.2) | 0.889 |

| Construction | 3.4 (1.1) | 3.0 (1.0) | 0.219 |

| Imitation | 3.4 (0.9) | 3.4 (0.8) | 0.745 |

| Language | |||

| 15-item BNT | 13.4 (1.6) | 13.1 (1.9) | 0.769 |

| Visuoperception | |||

| Poppelreuter answers | 9.4 (0.9) | 9.1 (0.9) | 0.448 |

| Poppelreuter errors | 0.9 (1.1) | 1.3 (1.1) | 0.313 |

| Luria’s Clock test | 2.6 (0.9) | 2.6 (0.9) | 0.938 |

| Executive functions | |||

| SKT seconds | 30.4 (7.8) | 33.1 (8.7) | 0.394 |

| Phonetic VF | 12.5 (4.4) | 10.6 (4.8) | 0.313 |

| Semantic VF | 11.1 (2.7) | 11.9 (3.7) | 0.588 |

| Abstract Reasoning | 9.3 (3.5) | 9.2 (2.5) | 0.654 |

| Global cognition | |||

| MMSE | 24.9 (2.3) | 26.1 (1.7) | 0.344 |

| The Clock test | 6.0 (1.6) | 5.4 (1.4) | 0.122 |

Statistically significant after Bonferroni’s correction.

15-OT: The 15-Objects test; D.S.: Standard Deviation; WMS-III: Wechsler Memory Scale-III; 15-item BNT: 15 items abreviated Boston Naming Test; SKT: Automatic Inhibition subtest of the Syndrom Kurtz Test (number of errors); VF: verbal fluency; MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination.

DISCUSSION

The results of the present study confirm and extend our understanding of the neuropsychological deficits in MCI and AD, and their neuroanatomical correlates. We replicated our prior findings that performance on the 15-OT becomes progressively less accurate as subjects move from normal cognition through MCI to AD [10,11].

Moreover, we found that the AD group had low levels of visuoperceptual performance (the 15-OT) and study entry, and this declined faster than that of the MCI patients; there was no change in performance in the EC over 2 years. This is consistent with other studies [26] that found that visual perception (as measured by the Hooper Visual Organization Test) is impaired in patients with AD and gradually deteriorates with disease progression. That study also found a significant decline in visuoperceptual performance of AD patients, but not in controls. To our knowledge, there are no previous reports about the progression of visual object perceptive deficits (and less with the 15-OT) in MCI. Moreover, the progression of visuoperceptual performance on the 15-OT has not been previously reported in normal aging, MCI or AD.

The performance of the AD patients declined significantly faster than MCI and controls not only on the 15-OT, but on the other tests of orientation, visuoperception, naming, executive functions and global cognition, as well. The performance by the AD patients also declined significantly faster than that of the controls on verbal learning and constructional praxis, which could indicate pervasive functional and structural CNS damage. Similar to previous studies [7,13], the decline in performance on several tests by the MCI patients was between that of the EC and AD groups, and only the change in 15-OT performance differed significantly between the MCI and control subjects. Moreover, we found that worsening performance on the 15-OT was associated with worsening performance on verbal and visual long-term memory performance. We conclude that the 15-OT may be useful to measure the cognitive deficit of AD from the earliest prodromal phase to the more severe dementia syndrome.

Cross-sectional SPECT studies find that with older age there is a reduction of global and local cerebral perfusion, mainly the frontal cortex and basal ganglia [30, 31, 32]. The one longitudinal study [33] did not find perfusion changes after a mean of two years, but the mean age of the subjects in that study was younger than that of our subjects (65 and 74 years, respectively). Nevertheless, we also found no changes in brain perfusion in the control group over two years. This finding might be related to the fact that the EC group did not show significant neuropsychological change over the study period.

The MCI patients had a significant decrease in cerebral perfusion over the two years of follow-up in bilateral middle and posterior cingulate, and left frontal, temporal and parietal areas, consistent with previous studies [34, 35, 36, 37, 38]. This may be a consequence of a disconnection between these regions and the entorhinal cortex [39], which is damaged early in the AD neuropathology. These group-level changes in perfusion may occur because at follow-up the MCI group included both patients who remained MCI and those who had converted to dementia. It may also be the case that because the MCI subjects are in an earlier stage of the disease than the AD patients, they have less neuropathological damage, and thus suffer a smaller reduction in perfusion than the AD patients over the same time interval.

In this, and other studies [38, 40, 41, 42] the AD patients showed more extensive progressive reduction of brain perfusion than did the MCI patients. Moreover, we found that the posterior cingulate gyrus, an area that is implicated in early AD and MCI [38, 43], suffered the greatest reduction of perfusion in MCI and AD over the two years of follow-up.

The SPM analysis allowed us to identify those brain regions where change in perfusion was associated with change in 15-OT performance. These regions included an area of the medial temporal cortex, left BA48 (retrosubicular or postsubicular) area. The postsubiculum is considered limbic association cortex [44], and it receives strong projections from hippocampal field CA1; it has projections to the entorhinal, visual and temporal association areas [44, 45].

At 2-year follow-up, 37.5% of MCI subjects had converted to dementia (all but one to AD type), for an annual conversion rate of 17.5%. This is similar to that reported in other series [16, 17, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50], but higher than those reported in population-based epidemiological studies [7, 51, 52, 53]. Similar to previous studies, the majority of our amnestic MCI who developed dementia, developed the AD type [49, 50, 54]. However, two of the MCI patients (5%) returned to normal cognitive functions over the 2 years [47, 49, 53].

Those MCI subjects who converted to AD dementia performed worse on a verbal memory recognition test at baseline. This observation reinforces the notion that recognition memory is associated with convertion to AD in MCI patients. It is consistent with previous findings demonstrating the relationship between poor performances on verbal memory recognition test and atrophy of the entorhinal cortex, which is one of the first areas affected in AD [55]. The poor recognition memory likely reflects a deficit in memory storage (vs., memory retrieval) and is characteristic of AD and other cortical dementias [56]. In AD patients, better performance on executive function tests is associated with better verbal recognition memory [57]. So, it may be the case that in the prodromal stages of AD (relatively) normal executive functions may be compensating for (mildly) affected verbal memory, but when verbal memory recognition performance get worse, this indicates that the patients are advancing closer to AD dementia.

Functional neuroimaging studies with SPECT have demonstrated that mild AD [34, 58, 59, 60, 61] and MCI patients [34, 35, 36, 37, 38] have reduced cerebral perfusion in the medial temporal lobe, the temporal-parietal cortex, posterior cingulate, precuneus and dorsolateral frontal cortex. Hypoperfusion in the medial temporal lobe, the posterior cingulate gyrus and precuneus, and the parietal, occipital and frontal cortex have been found in those MCI patients who later progressed to dementia [35, 36, 57, 62, 63, 64, 65]. In the present study, we predicted that the MCI subjects who would convert to AD dementia would have a pattern of perfusion similar to that seen in the AD patients. However, we did not find differences between the MCI groups (converters and non-converters), possibly because some of our MCI non-converters subjects were also next to conversion, as previously reported that the most conversions occur within the first 3 years [19].

In the present study, the verbal recognition memory test scores, unlike the SPECT data, showed differences between MCI converters and non-converters. This finding could be explained by the fact that detectable cognitive changes may occur prior to detectable changes in brain perfusion (that is, a measurement sensitivity issue) or because other cerebral changes such as network disruptions, or volume decreases result in an apparent sparing of blood flow.

The present study has several limitations. As noted previously [11], we did not have anatomical MRI scans from participants to perform atrophy corrections, so some of our results may have been related to focal regional atrophy. We also cannot determine whether structural changes can explain the functional abnormalities. Another limitation in the interpretation of the results of the SPECT studies in healthy elderly control subjects is the absence of structural imaging in some cases, but in the follow-up analysis we only included those subjects with a preserved cognitive performance during all the study period, and we excluded the 3 subjects who showed cognitive impairment due to vascular and/or depressive aetiology. It would have been useful to have included an “active” condition to compare with the resting state in the functional images, on the assumption that this may have been more sensitive to subtle alterations in function. However, it is important to note that our study had the advantage that all of the subjects were prospectively enrolled in the same centre, that all variables were collected at all visits, and that only a small number of subjects discontinued the study (and none were lost to follow-up).

In conclusion, our findings reinforces the idea that the 15-OT may be a useful, and cost-effective tool (quick and easy to administer in clinical practice) for differentiating between MCI and AD, and for measuring the cognitive deficit of AD from the earliest prodromal phase to the more severe dementia syndrome. It provides a gradation of impairment from normal aging to AD, and poorer performances is found related to poorer performance on the verbal and visual retention tests, and perfusion in the postsubicular area. Moreover, performance on a verbal memory recognition test seems to be more useful than SPECT in differentiating between those MCI who will develop AD and those who will not. So, SPECT and 15-OT appear to have the potential to differentiate between the progression of normal aging, MCI and AD. However, longitudinal studies are needed to determine the contribution of 15-OT as a predictor of conversion to AD from MCI.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Health (FISS PI070739) from Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Madrid), by funds from Fundació ACE, Institut Català de Neurociències Aplicades, and by the University of Pittsburgh Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (AG05133). We are grateful to companions who have contributed to ensure that subjects continued participating in the study: Rosa Balsalobre, MªJosé Castillón, Charo Romero, Carmen Quindos; and to all participants and their caregivers.

References

- 1.Small BJ, Gagnon E, Robinson B. Early identification of cognitive deficits: preclinical Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Geriatrics. 2007;62:19–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bäckman L, Small BJ, Fratiglioni L. Stability of the preclinical episodic memory deficit in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2001;124:96–102. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.1.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amieva H, Jacqmin-Gadda H, Orgogozo JM, Le Carret N, Helmer C, Letenneur L, Barberger-Gateau P, Fabrigoule C, Dartigues JF. The 9 year cognitive decline before dementia of the Alzheimer type: a prospective population-based study. Brain. 2005;128:1093–1101. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levinoff EJ, Saumier D, Chertkov H. Focused attention deficits in partients with Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impaiment. Brain Cogn. 2005;57:127–130. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2004.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tales A, Haworth J, Nelson S, Snowden RM, Wilcock G. Abnormal visual search in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurocase. 2005;11:80–84. doi: 10.1080/13554790490896974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tales A, Bayer AJ, Haworth J, Snowden RJ, Philips M, Wilcock G. Visual search in mild cognitive impairment: A longitudinal study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;24:151–160. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-101818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bennett DA, Wilson RS, Schneider JA, Evans DA, Beckett LA, Aggarwal NT, Barnes LL, Fox JH, Bach J. Natural history of mild cognitive impairment in older persons. Neurology. 2002;59:198–205. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.2.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Espinosa A, Alegret M, Boada M, Vinyes G, Valero S, Martínez-Lage P, Peña-Casanova J, Becker JT, Wilson BA, Tárraga L. Ecological assessment of executive functions in Mild Cognitive Impairment and mild Alzheimer’s Disease. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2009;15:751–757. doi: 10.1017/S135561770999035X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nordlund A, Rolstad S, Hellström P, Sjögren M, Hansen S, Wallin A. The Goteborg MCI study: mild cognitive impairment is a heterogeneous condition. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:1485–1490. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.050385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alegret M, Boada-Rovira M, Vinyes-Junqué G, Valero S, Espinosa A, Hernández I, Modinos G, Rosende-Roca M, Mauleón A, Becker JT, Tárraga L. Detection of visuoperceptual deficits in preclinical and mild Alzheimers disease. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2009;31:860–867. doi: 10.1080/13803390802595568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alegret M, Vinyes-Junqué G, Boada M, Martínez-Lage P, Cuberas G, Espinosa A, Roca I, Hernández I, Valero S, Rosende-Roca M, Mauleón A, Becker JT, Tárraga L. Brain perfusion correlates of visuoperceptual deficits in Mild Cognitive Impairment and mild Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;21:557–567. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-091069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson DK, Storandt M, Morris JC, Calvin JE. Longitudinal study of the transition from healthy aging to Alzheimer Disease. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:1254–1259. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bozoki A, Giordani B, Heidebrink JL, Berent S, Foster NL. Mild cognitive impairment predict dementia in nondemented elderly patients with memory loss. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:411–416. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.3.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alexopoulos P, Grimmer T, Perneczky R, Domes G, Kurz A. Do all patients with mild cognitive impairment progress to dementia? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1008–1010. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tabert MH, Manly JJ, Liu X, Pelton GH, Rosenblum S, Jacobs M, Zamora D, Goodkind M, Bell K, Stern Y, Devanand DP. Neuropsychological prediction of conversion to Alzheimer disease in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:916–924. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.8.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nordlund A, Rolstad S, Göthlin M, Edman A, Hansen S, Wallin A. Cognitive profiles of incipient dementia in the Goteborg MCI Study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2010;30:403–410. doi: 10.1159/000321352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entitiy. J Intern Med. 2004;256:183–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Devanand DP, Pradhaban G, Liu X, Khandji A, De Santi S, Segal S, Rusinek H, Pelton GH, Honig LS, Mayeux R, Stern Y, Tabert MH, de Leon MJ. Hippocampal and entorhinal atrophy in mild cognitive impairment: prediction of Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2007;68:828–836. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000256697.20968.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Devanand DP, Liu X, Tabert MH, Pradhaban G, Cuasay K, Bell K, de Leon MJ, Doty RL, Stern Y, Pelton GH. Combining early markers strongly predicts conversion from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64:871–879. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fleischer AD, Sun S, Taylor C, Ward CP, Gamst AC, Petersen RC, Jack CR, Aisen RS, Thal LJ. Volumetric MRI vs clinical predictors of Alzheimer disease in mild cognitive impairment. Neurology. 2008;70:191–199. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000287091.57376.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ewers M, Walsh C, Trojanowski JQ, Shaw LM, Petersen RC, Jack CR, Jr, Feldman HH, Bokde AL, Alexander GE, Scheltens P, Vellas B, Dubois B, Weiner M, Hampel H North American Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) Prediction of conversion from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease dementia based upon biomarkers and neuropsychological test performance. Neurobiol Aging. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.10.019. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, Dubois B, Feldman HH, Fox NC, Gamst A, Holtzman DM, Jagust WJ, Petersen RC, Snyder PJ, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Phelps CH. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mendez MF, Mendez MA, Martin R, Smyth KA, Whitehouse PJ. Complex visual disturbances in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1990;40:439–443. doi: 10.1212/wnl.40.3_part_1.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kurylo DD, Corkin S, Rizzo JF, Growdon JH. Greater relative impairment of object recognition than visuospatial abilities in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychology. 1996;10:74–81. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fujimori M, Imamura T, Hirono N, Ishii K, Sasaki M, Mori E. Disturbances of spatial vision and object vision correlate differently with regional cerebral glucose metabolism in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychologia. 2000;38:1356–1361. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(00)00060-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paxton JL, Peavy GM, Jenkins C, Rice VA, Heindel WC, Salmon DP. Deterioration of visual-perceptual organization in Alzheimer’s disease. Cortex. 2007;43:967–975. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(08)70694-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hof PR, Bouras C. Object recognition deficit in Alzheimer’s disease: Possible disconnection of the occipito-temporal component of the visual system. Neurosci Lett. 1991;122:53–56. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90191-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lueschow A, Miller EK, Desimone R. Inferior temporal mechanisms for invariant object recognition. Cereb Cortex. 1994;4:523–531. doi: 10.1093/cercor/4.5.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Genovese CR, Lazar NA, Nichols T. Thresholding of statistical maps in functional neuroimaging using the false discovery rate. Neuroimage. 2002;15:870–878. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Waldemar G, Hasselbalch SG, Andersen AR, Delecluse F, Petersen P, Johnsen A, Paulson OB. Tc99m-d, I-HMPAO and SPECT of the brain in normal aging. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1991;11:508–521. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1991.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Markus HS, Ring H, Kouris K, Costa DC. Alterations in regional cerebral blood flow, with increased temporal interhemispheric asymmetries, in the normal elderly: an HMPAO SPECT study. Nucl Med Commun. 1993;14:628–633. doi: 10.1097/00006231-199308000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krausz Y, Bonne O, Gorfine M, Karger H, Lerer B, Chisin R. Age-related changes in brain perfusion of normal subjects detected by 99mTc-HMPAO SPECT. Neuroradiology. 1998;40:428–434. doi: 10.1007/s002340050617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Celsis P, Agniel A, Cardebat D, Démonet JF, Ousset PJ, Puel M. Age related cognitive decline: a clinical entity? A longitudinal study of cerebral blood flow and memory performance. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1997;62:601–608. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.62.6.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson KA, Jones K, Holman BL, Becker JA, Spiers PA, Satlin A, Albert MS. Preclinical prediction of Alzheimer’s disease using SPECT. Neurology. 1998;50:1563–1571. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.6.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hirao K, Ohnishi T, Hirata Y, Yamashita F, Mori T, Moriguchi Y, Matsuda H, Nemoto K, Imabayashi E, Yamada M, Iwamoto T, Arima K, Asada T. The prediction of rapid conversion of Alzheimer’s disease in mild cognitive impairment using regional cerebral blood flow SPECT. Neuroimage. 2005;28:1014–1021. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.06.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kogure D, Matsuda H, Ohnishi T, Asada T, Uno M, Kunihiro T, Nakano S, Takasaki M. Longitudinal evaluation of early Alzheimer’s disease using brain perfusion SPECT. J Nucl Med. 2000;41:1155–1162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nobili F, Frisoni GB, Portet F, Verhey F, Rodriguez G, Caroli A, Touchon J, Calvini P, Morbelli S, De Carli F, Guerra UP, Van de Pol LA, Visser PJ. Brain SPECT in subtypes of mild cognitive impairment. Findings from the DESCRIPA multicenter study. J Neurol. 2008;255:1344–1353. doi: 10.1007/s00415-008-0897-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnson KA, Moran EK, Becker JA, Blacker D, Fischman AJ, Albert MS. Single photon emission computed tomography perfusion differences in mild cognitive impairment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78:240–247. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.096800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mosconi L, Pupi A, De Cristofaro MT, Fayyaz M, Sorbi S, Herholz K. Functional interactions of the entorhinal cortex: An 18F-FDG PET study on normal aging and Alzheimer’s disease. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:382–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang C, Wahlund LO, Svensson L, Winblad B, Julin P. Cingulate cortex hypoperfusion predicts Alzheimer’s disease in mild cognitive impairment. BMC Neurology. 2002;2:9–14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-2-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang C, Wahlund LO, Almkvist O, Elehu D, Svensson L, Jonsson T, Winblad B, Julin P. Voxel- and VOI-based analysis of SPECT CBF in relation to clinical and psychological heterogeneity of mild cognitive impairment. Neuroimage. 2003;19:1137–1144. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00168-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Borroni B, Anchisi D, Paghera B, Vicini B, Kerrouche N, Garibotto V, Terzi A, Vignolo LA, Di Luca M, Giubbin Padovani A, Perani D. Combined 99mTc-ECD SPECT and neuropsychological studies in MCI for the assessment of conversion to AD. Neurobiol Aging. 2006;27:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Raichle ME, Snyder AZ. A default mode of brain function: a brief history of an evolving idea. Neuroimage. 2007;37:1083–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vogt BA, Miller MW. Cortical connections between rat cingulate cortex and visual, motor, and postsubicular cortices. J Comp Neurol. 1983;216:192–210. doi: 10.1002/cne.902160207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cenquizca LA, Swanson LW. Spatial organization of direct hippocampal field CA1 axonal projections to the rest of the cerebral cortex. Brain Res Rev. 2007;56:1–26. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morris JC, Storandt M, Miller JP, McKeel DW, Price JL, Rubin EH, Berg L. Mild Cognitive Impairment represents early-stage Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:397–405. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.3.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gauthier S, Reisbert B, Zaudig M, Petersen RC, Ritchie K, Broich K, Belleville S, Brodaty H, Bennett D, Chertkow H, Cummings JL, de Leon M, Feldman H, Ganguli M, Hampel H, Scheltens P, Tierney MC, Whitehouse P, Winblad B International Psychogeriatric Association Expert Conference on mild cognitive impairment . Mild cognitive impairment. Lancet. 2006;367:1262–1270. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68542-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Griffith HR, Netson KL, Harrell LE, Zamrini EY, Brockington JC, Marson DC. Amnestic mild cognitive impairment: diagnostic outcomes and clinical prediction over a two-year time period. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2006;12:166–175. doi: 10.1017/S1355617706060267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fischer P, Jungwirth S, Zehetmayer S, Weissgram S, Hoenigschnabl S, Gelpi E, Krampla W, Tragl KH. Conversion from subtypes of mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer dementia. Neurology. 2007;68:288–291. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000252358.03285.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rountree SD, Waring SC, Chan WC, Lupo PJ, Darby EJ, Doody Importance of subtle amnestic and nonamnestic deficits in mild cognitive impairment: Prognosis and conversion to dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2007;24:476–482. doi: 10.1159/000110800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ritchie K, Artero S, Touchon J. Classification criteria for mild cognitive impairment. A population-based validation study. Neurology. 2001;56:37–42. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Larrieu S, Letenneur L, Orgogozo JM, Fabrigoule C, Amieva H, Le Carret N, Barberger-Gateau P, Dartigues JF. Incidence and outcome of mild cognitive impairment in a population-based prospective cohort. Neurology. 2002;59:1594–1599. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000034176.07159.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ganguli M, Dodge HH, Shen C, DeKosky ST. Mild cognitive impairment, amnestic type: an epidemiologic study. Neurology. 2004;63:115–121. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000132523.27540.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dubois B, Feldman HH, Jacova C, Cummings JL, DeKosky ST, Barberger-Gateau P, Delacourte A, Frisoni G, Fox NC, Galasko D, Gauthier S, Hampel H, Jicha GA, Meguro K, O’Brien J, Pasquier F, Robert P, Rossor M, Salloway S, Sarazin M, de Souza LC, Stern Y, Visser PJ, Sheltens P. Revising the definition of Alzheimer’s disease: a new lexicon. Lancet Neurol. 2007;9:1118–1127. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70223-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wolk DA, Dickerson BC Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative . Fractionating verbal episodic memory in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage. 2011;54:1530–1539. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Massman PJ, Delis DC, Butters N, Dupont RM, Gillin JC. The subcortical dysfunction hypothesis of memory deficits in depression: neuropsychological validation in a subgroup of patients. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1992;14:687–706. doi: 10.1080/01688639208402856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gleichgerrcht E, Torralva T, Martinez D, Roca M, Manes F. Impact of executive dysfunction on verbal memory performance in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;23:79–85. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Matsuda H, Kitayama N, Ohnishi T, Asada T, Nakano S, Sakamoto S, Imabayashi E, Katoh A. Longitudinal evaluation of both morphologic and functional changes in the same individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. J Nucl Med. 2002;43:304–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pearlson GD, Harris GJ, Powers RE, Barta PE, Camargo EE, Chase GA, Noga JT, Tune LE. Quantitative changes in mesial temporal volume, regional cerebral blood flow, and cognition in Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:402–408. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820050066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Encinas M, De Juan R, Marcos A, Gil P, Barabash A, Fernández C, De Hugarte C, Cabranes JA. Regional cerebral blood flow assessed with 99mTc-ECD SPET as a marker of progression of mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2003;30:1473–1480. doi: 10.1007/s00259-003-1277-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ashford JW, Shih WJ, Coupal J, Shetty R, Schneider A, Cool C, Aleem A, Kiefer VH, Mendiondo MS, Schmitt FA. Single SPECT measures of cerebral cortical perfusion reflect time-index estimation of dementia severity in Alzheimer’s disease. J Nucl Med. 2000;41:57–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nobili F, De Carli F, Frisoni GB, Portet F, Verhey F, Rodriguez G, Caroli A, Touchon J, Morbelli S, Guerra UP, Dessi B, Brugnolo A, Visser PJ. SPECT predictors of cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease in mild cognitive impairment. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;17:761–772. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Devanand DP, Van Heertum RL, Kegeles LS, Liu X, Jin ZH, Pradhaban G, Rusinek H, Pratap M, Pelton GH, Prohovnik I, Stern Y, Mann JJ, Parsey R. 99m Hexamethyl-Propylene-Aminoxime Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography prediction of conversion from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18:959–972. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181ec8696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Huang C, Wahlund LO, Svensson L, Winblad B, Julin P. Cingulate cortex hypoperfusion predicts Alzheimer’s disease in mild cognitive impairment. BMC Neurology. 2002;2:9–14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-2-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wolf H, Jelic V, Gertz HJ, Nordberg A, Julin P, Wahlund LO. A critical discussion of the role of neuroimaging in mild cognitive impairment. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl. 2003;179:52–76. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0404.107.s179.10.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.