Abstract

The ability of bacteria to adapt to a changing environment is essential for their survival. One mechanism used to facilitate behavioral adaptations is the second messenger signaling molecule bis-(3′-5′)-cyclic dimeric guanosine monophosphate (c-di-GMP). c-di-GMP is widespread throughout the bacterial domain and plays a vital role in regulating the transition between the motile planktonic lifestyle and the sessile biofilm forming state. This second messenger also controls the virulence response of pathogenic organisms and is thought to be connected to quorum sensing, the process by which bacteria communicate with each other. The intracellular concentration of c-di-GMP is tightly regulated by the opposing enzymatic activities of diguanlyate cyclases and phosphodiesterases, which synthesize and degrade the second messenger, respectively. The change in the intracellular concentration of c-di-GMP is directly sensed by downstream targets of the second messenger, both protein and RNA, which induce the appropriate phenotypic response. This review will summarize our current state of knowledge of c-di-GMP signaling in bacteria with a focus on protein and RNA binding partners of the second messenger. Efforts towards the synthesis of c-di-GMP and its analogs are discussed as well as studies aimed at targeting these macromolecular effectors with chemically synthesized cyclic dinucleotide analogs.

Second messenger signaling in bacteria

Signal transduction is used by organisms from all domains of life to sense changes in the environment and translate these cues into metabolic, physiological, and behavioral adaptations1. These regulatory networks are complex and rely on the coordination of many different interacting components to induce the appropriate biological response. One vital component of many signaling pathways are intracellular small molecules known as second messengers2,3 (Figure 1). Second messengers relay external stimuli (i.e. the first message) received by cell-surface receptors to macromolecular effectors within the cell. The intracellular concentration of the second messenger is tightly controlled by proteins that synthesize or degrade the small molecule in response to specific extracellular inputs. These changing second messenger levels are sensed by specific effector molecules, which, in response to second messenger binding, act to induce the appropriate physiological output2,3. The behavioral responses induced by second messengers are often critical for survival, underscoring the crucial role of these small molecules in signal transduction.

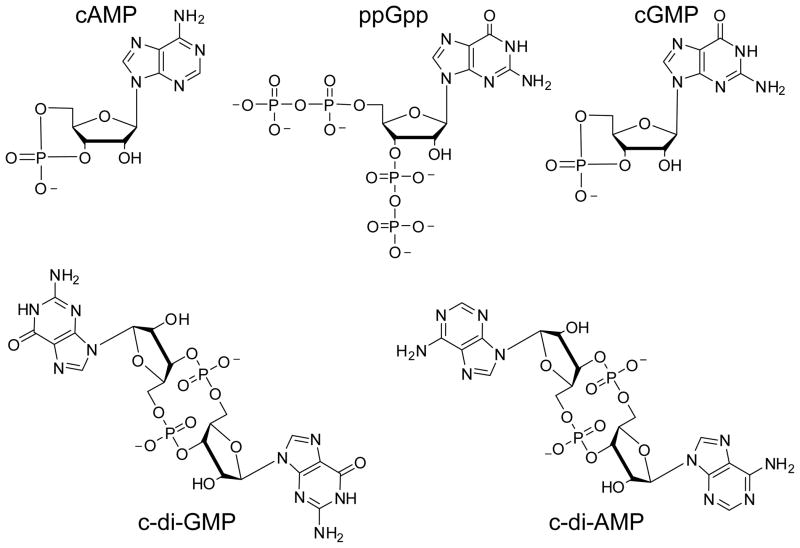

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of known bacterial nucleotide based second messenger signaling molecules. Bacteria utilize both cyclic mononucleotides and cyclic dinucleotides for signaling.

For many years, it has been known that bacteria, and also eukaryotes, utilize the nucleotide based second messengers 3′-5′-cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) and guanosine tetraphosphate/pentaphosphate ((p)ppGpp)) for signaling3–6 3 (Figure 1). And while the role of the well known eukaryotic second messenger 3′-5′-cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) in bacterial signaling has been controversial, recent evidence suggests that cGMP may function to regulate prokaryotic development7. In bacteria, cAMP primarily regulates catabolite repression, glucose sensing, and the usage of alternative carbon sources4, whereas (p)ppGpp is produced in response to cellular stress and starvation conditions5,6. Both of these second messengers interact with a single class of transcription factors, the cAMP receptor protein (CRP) for cAMP and RNA polymerase for (p)ppGpp, which allosterically regulates the transcription of target genes to facilitate the appropriate behavioral adaptations3. Thus, cAMP and (p)ppGpp control a diverse set of biological processes primarily through transcriptional regulation.

In recent years, the scope of bacterial nucleotide based second messengers has expanded well beyond that of cAMP and (p)ppGpp with the realization that dinucleotide signaling molecules are also prevalent within this domain of life7. Bis-(3′-5′)-cyclic dimeric guanosine monophosphate (c-di-GMP) was the first of this class to be recognized as a global second messenger8,9 (Figure 1). Similar to cAMP and (p)ppGpp, c-di-GMP regulates many different biological processes and one of its most crucial functions is to mediate the transition between the motile, planktonic lifestyle and the sessile, biofilm forming state10–14. In addition, the related dinucleotide bis-(3′-5′)-cyclic dimeric adenosine monophosphate (c-di-AMP) has also gained attention as another potentially global bacterial second messenger involved in controlling DNA damage response, cell wall homeostasis, and membrane stress15,16 (Figure 1). These recent advances in uncovering new bacterial second messengers have raised important questions related to their overall role in signal transduction, how bacteria regulate these multiple pathways in parallel, the specific mechanisms by which these small molecules induce many different physiological responses and how to design small molecule probes of these pathways to function as chemical tools and novel therapeutics. This review will focus specifically on the c-di-GMP signaling pathway, recent advances in the synthesis of second messenger analogs, and the use of these analogs to target c-di-GMP binding partners.

c-di-GMP is a ubiquitous bacterial second messenger that regulates diverse biological processes

The enzymes that synthesize and degrade c-di-GMP

c-di-GMP was first discovered during the late 1980’s in the lab of Moshe Benziman who demonstrated that it allosterically activated the membrane bound enzyme cellulose synthase in Gluconoacetobacter xylinus17. Furthermore, Benziman and coworkers proposed a model for the regulation of cellulose production in this organism via the enzymatic synthesis and degradation of c-di-GMP based on the ability of purified membrane extracts to metabolize this dinucleotide17. However, it wasn’t until about a decade later that the specific protein domains responsible for c-di-GMP turnover were identified18 and found to be widely distributed throughout the bacterial domain19. This suggested a much broader role for this small molecule in regulating bacterial behavior and physiology19,20. c-di-GMP is now recognized as a global bacterial second messenger signaling molecule that mediates a wide variety of biological processes which extend well beyond its initially characterized role in cellulose production.

c-di-GMP is synthesized inside the cell from two molecules of GTP by GGDEF domain diguanylate cyclases (DGCs)21,22 (Figure 2). It is degraded primarily by EAL domain phosphodiesterases (PDEs) to the linear dinucleotide pGpG23–25 (Figure 2). A second, less common class of c-di-GMP phosphodiesterases has also been identified that display no sequence similarity to the EAL domain PDEs known as the HD-GYP domain PDEs26,27. This class of PDEs degrades c-di-GMP to two molecules of GMP through a pGpG intermediate27. These c-di-GMP metabolizing enzymes are named for the conserved amino acids in the active site that are critical for catalysis and therefore the ability to regulate the intracellular concentration of the second messenger3. GGDEF domain DGCs often contain a secondary site of the sequence RxxD, referred to as the I-site, that functions as a high affinity c-di-GMP binding motif and controls DGC activity through product feedback inhibition28,29. GGDEF, EAL and HD-GYP domains are widely found throughout bacterial genomes suggesting that c-di-GMP is utilized as a second messenger by many bacterial species to control behavioral outcomes19. In contrast to cAMP and (p)ppGpp which are used by both prokaryotes and eukaryotes for signaling3, the GGDEF, EAL and HD-GYP domains are absent from the genomes of archaea and eukaryotes suggesting that c-di-GMP is a bacterial specific regulatory molecule19,30.

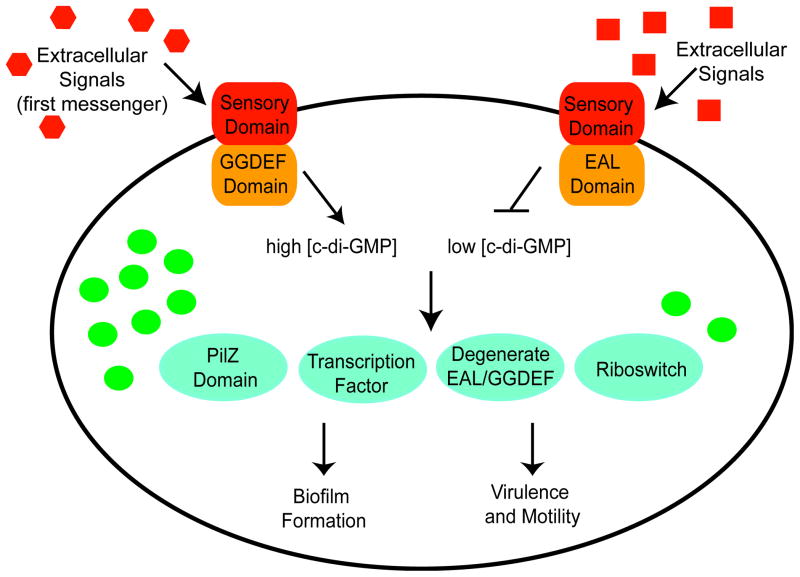

Figure 2.

Schematic of c-di-GMP signaling in bacteria. c-di-GMP metabolizing enzymes are shown as orange rectangles, c-di-GMP molecules are represented by green circles, and receptors of the second messenger are indicated in teal circles. Similar to the EAL domain, some bacteria also utilize HD-GYP domain proteins to decrease intracellular levels of c-di-GMP. Phenotypic outputs induced by high concentrations of the second messenger are indicated on the bottom left and those induced by low concentrations are indicated on the bottom right.

Biological processes regulated by c-di-GMP

Analogous to cAMP and (p)ppGpp signaling, one of the hallmark themes of c-di-GMP signaling is the remarkable diversity of physiological processes in which this second messenger plays a regulatory role. c-di-GMP is often referred to as the ‘lifestyle molecule’ because one of its primary functions is to mediate the transition between the sessile, biofilm forming state and the motile, planktonic lifestyle by inversely regulating the expression of genes necessary for motility and cell surface adhesion factors3,10,13,31. It is now well established that high intracellular concentrations of c-di-GMP promote biofilm formation whereas low intracellular concentrations stimulate motility31 (Figure 2). However, before it was directly demonstrated that GGDEF and EAL domain proteins synthesized and degraded c-di-GMP, the realization that this dinucleotide was a global second messenger emerged from genetic studies linking diverse biological phenotypes such as rugose colony formation, biofilm matrix development, virulence, and twitching motility to these protein domains20.

In addition to its prevalent role in regulating bacterial lifestyle processes, the importance of this second messenger in controlling bacterial pathogenesis is also now well established30,32–34. Vibrio cholerae was the first pathogenic organism for which a link between c-di-GMP and virulence response was demonstrated32. Low intracellular levels of c-di-GMP, promoted by the EAL domain phosphodiesterase VieA, were shown to enhance the production of cholera toxin, the virulence factor responsible for colonization of the mammalian intestine during cholera infection. Mutation of VieA to abolish its PDE activity decreased expression of cholera toxin and reduced the ability of the bacterium to colonize the intestine of a mouse model of cholera, suggesting that c-di-GMP repressed the transcription of virulence factors32. The critical function of c-di-GMP in regulating virulence response has now been demonstrated for other known human pathogens, including the causative agents of gastroenteritis33 and Lyme disease33,34.

This second messenger also regulates other biological processes including cell differentiation, cell morphology, cell-cell communication, exopolysaccharide matrix production, expression of virulence factors, flagellum biosynthesis, and pilus assembly9. c-di-GMP has also been linked to quorum sensing, the process by which bacteria sense and communicate with each other35,36, and the cAMP signaling pathway37. Key components of both cAMP signaling and quorum sensing have been shown to alter the expression of genes encoding GGDEF and EAL domain proteins37,38, underscoring the complexity of c-di-GMP-mediated signaling.

Regulation of c-di-GMP biosynthesis by GGDEF and EAL domain proteins

For c-di-GMP to trigger the appropriate behavioral responses, the intracellular concentration of this second messenger must be tightly controlled by the opposing enzymatic activities of DGCs and PDEs. However, one of the more puzzling aspects relating to the distribution of GGDEF and EAL domain proteins throughout bacterial genomes is the duplication of these enzymes within a single organism10,14. For example, Escherichia coli encodes 17 EAL domains and 19 GGDEF domains, while Vibrio vulnificus is predicted to have 33 EAL domains and 66 GGDEF domains9. This observation raises the important question of how the enzymatic activities of these proteins with identical function are regulated in parallel. In addition, many GGDEF-EAL dual domain proteins exist where one of the domains is usually catalytically inactive and instead possesses a regulatory function10,39,40. However, bi-functional GGDEF-EAL composite proteins that posses both cyclase and phosphodiesterase activity exist41,42. This observation raises the related question of how both enzymatic activities are regulated within a single protein. Bacteria have evolved two distinct mechanisms for controlling the activity of GGDEF and EAL domain proteins. The first is by linking these domains to additional regulatory domains that sense specific signals and control GGDEF and/or EAL function in response, and the second is by localizing these proteins to specific parts of the cell and inducing expression only at certain times10.

Signal sensing and regulatory accessory domains

Based on genomic sequencing, it is estimated that 50 to 70% of all GGDEF and EAL domain proteins contain an additional accessory domain that functions to either sense a specific environmental signal or produce an output40. This facilitates the direct coupling of an external or intracellular signal input to either c-di-GMP synthesis or degradation10–13. A wide variety of either integral membrane or cytoplasmic sensory domains are linked to GGDEF and EAL domain proteins, which can sense signals such as light, gases (NO and O2), phosphorylation, redox conditions and binding of proteins, DNA and small molecule ligands9–11. In addition, a large majority of GGDEF-EAL dual domain proteins predicted to possess both enzymatic activities have an added regulatory domain that is thought to control the selection between these two activities40. However, the specific molecular details of how the opposing enzymatic activities of many of these bifunctional proteins are regulated within the cell have yet to be determined. Collectively, these observations suggest that DGCs and PDEs are functionally diversified such that numerous environmental and intracellular signals can be integrated into the c-di-GMP regulatory network9,10.

Spatial and temporal control of c-di-GMP signaling modules

Another strategy employed by bacteria to manage the redundancy of GGDEF and EAL domain proteins is spatial sequestration of these c-di-GMP signaling components10,12. DGC and PDE enzymes control the local concentration of c-di-GMP, which is then only available to a specific, local target molecule12. Because specific PDEs and DGCs are associated with different phenotypic outputs, the co-localization of both c-di-GMP metabolic enzymes and receptors to specific parts of the cell is a useful strategy for delegating specific c-di-GMP signaling systems to carry out particular cellular tasks12,43.

Temporal regulation is also utilized by bacteria to coordinate the catalytic functions of the numerous GGDEF and EAL domains encoded in a single genome10. In this case, both the cellular expression levels and activities of these proteins are expected to change in response to specific environmental or intracellular stimuli at discreet times. Consistent with this idea, a recent study in Escherichia coli looking at the expression levels of all the GGDEF and EAL domain proteins under varying growth conditions demonstrated that these enzymes were differentially expressed in response to changes in temperature, growth phase, and media44. The observation that the majority of GGDEF and EAL domains are linked to signal sensing domains is also consistent with this model, as this domain arrangement implies that certain proteins are not constitutively active, but are instead only activated in response to specific stimuli.

The spatial and temporal sequestration of c-di-GMP signaling components are not likely to be mutually exclusive. This is best demonstrated by the role of the specific DGC PleD from Caulobacter crescentus in mediating the transition from a motile swarmer cell, to a sessile stalked cell9,22,43. Its ability to synthesize c-di-GMP is dependent on an intracellular signal (temporal) whereas its physiological output requires it to be localized to a specific position in the cell to properly exert its function (spatial). It is clear that a great deal of complexity is involved in organizing c-di-GMP signaling within a particular organism.

Macromolecular targets of c-di-GMP

As a second messenger, c-di-GMP directly interacts with macromolecular targets to communicate the extracellular signals received by cell surface receptors (Figure 2, Table 1). However, one of the greatest challenges in understanding the mechanisms of c-di-GMP signaling proves to be the identification of the receptor molecules that recognize and bind this second messenger. Unlike the second messengers cAMP and (p)ppGpp, which both act by primarily binding a single protein receptor3, the macromolecules that sense c-di-GMP are highly diverse and cannot be identified by a single binding site13,45. In addition to several classes of protein receptors that bind c-di-GMP, RNA receptors of the second messenger have also been identified as part of this signaling pathway (Table 1).

Table 1.

Receptors that sense the second messenger c-di-GMP.

| Class of Receptor | Example | Organism | Biological Output | Level of action |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PilZ Domain Protein | BcsA | G. xylinus | Cellulose synthesis | Post-Translational |

| YcgR | E. coli | Swimming velocity | Post-Translational | |

| DcgR | C. crescentus | Motility | Post-Translational | |

| Alg44 | P. aeruginosa | Alginate synthesis | Post-Translational1 | |

|

| ||||

| Transcription Factor | FleQ | P. aeruginosa | Flagella expression | Transcriptional |

| VpsT | V. cholerae | EPS matrix synthesis | Transcriptional | |

| Clp | X. campestris | Virulence gene expression | Transcriptional | |

| VpsR | V. cholerae | Virulence gene expression | Transcriptional | |

| MrkH | K. pneumoniae | Fimbrae production | Transcriptional | |

|

| ||||

| Degenerate EAL | FimX | P. aeruginosa | Twitching motility | Post-Translational |

| LapD | P. fluorescens | Biofilm formation | Post-Translational | |

|

| ||||

| Degenerate GGDEF | PopA | C. crescentus | Cell cycle progression | Post-Translational |

| CdgG | V. cholerae | Rugosity | Unknown | |

| SmgT | M. xanthus | Extracellular matrix production | Post-Translational | |

|

| ||||

| I-Site | PelD | P. aeruginosa | Pellicle formation | Unknown |

|

| ||||

| Class I Riboswitch | Vc2 | V. cholerae | Rugosity | Translational |

| Cd1 | C. difficile | Flagella expression | Transcriptional | |

|

| ||||

| Class II Riboswitch | 84 Cd | C. difficile | Expression of a cell surface protein | Translational |

| Bha-1-1 | B. halodurans | Outermembrane protein synthesis | Transcriptional | |

Hypothesized to regulate alginate biosynthesis via a protein-protein interaction.

Proteins that recognize and bind c-di-GMP

The first class of macromolecules found to directly bind c-di-GMP was the PilZ protein domain, which was originally thought to be the long sought after c-di-GMP binding partner46,47 (Table 1). In accordance with this initial impression, the first protein identified to be regulated by c-di-GMP, the cellulose synthase protein BcsA from Gluconoacetobacter xylinus, contains a PilZ domain46,48. In addition, the phylogenetic distribution of these domains was similar to that of the GGDEF and EAL domain proteins46,47,49. The PilZ domain proteins are currently the most commonly occurring protein for c-di-GMP signaling with nearly 4000 sequences (Pfam Search: PF07238) identified in approximately 1100 bacterial species. In enterobacteria, PilZ domains are often found C-terminal to the protein domain YcgR (Pfam PF07317), which interacts with additional proteins that control flagellar rotation and motility47,50,51. In Vibrio cholerae, these c-di-GMP binding proteins have been implicated in biofilm formation, motility, and virulence49, and for Pseudomonas aeruginosa, in alginate biosynthesis52. However, not all species that utilized this second messenger for signaling encoded a PilZ domain in their genome, suggesting that other effectors must exist46. As predicted, additional classes of c-di-GMP binding proteins have now been identified that include transcription factors53–58, degenerate GGDEF and EAL domain proteins59–63, and I-site effectors64.

Thus far, five distinct classes of transcription factors have been identified that directly bind c-di-GMP and regulate the expression of target genes (Table 1). FleQ from Pseudomonas aeruginosa was the first transcription factor identified to directly interact with c-di-GMP 53. FleQ inversely regulates the transcription of genes necessary for exopolysaccharide (EPS) matrix production and flagella biosynthesis53. Approximately 200 homologs of FleQ (Pfam PF06490) in 200 different bacterial species have been found, but their ability to bind the second messenger and regulate transcription in a c-di-GMP dependent manner remains to be verified.

In Vibrio cholerae, two classes of c-di-GMP binding transcription factors have been identified, VpsT and VpsR. VpsT upregulates the expression of EPS producing genes in a c-di-GMP dependent fashion54. VpsR was shown to be a transcriptional activator of biofilm formation57. c-di-GMP binding to VpsR activates expression of a protein known to both activate virulence gene expression and regulate the quorum sensing pathway at low cell density. Although the implication of this finding is not yet clear, it is thought that Vibrio cholerae integrates information from both quorum sensing and c-di-GMP signaling to appropriately adapt to its current environment57.

Another family of c-di-GMP binding transcription factors identified was Clp, which is a subset of the cyclic AMP receptor protein (CRP) super family. Clp is important for regulating genes involved in the pathogenesis of xanthomonads55,56. The cyclic nucleotide monophosphate (cNMP) binding domain of CRP contains six highly conserved amino acid residues that confer specificity for cAMP recognition. However, the nucleotide binding site of Clp differs from that of CRP by a single amino acid substitution, which defines its specificity for c-di-GMP56.

More recently, MrkH from Klebsiella pneuomoniae has also been identified as a c-di-GMP dependent transcriptional regulator58. In the presence of c-di-GMP, MrkH activates the expression of genes encoding fimbriae production during biofilm formation. MrkH is distinct from other known c-di-GMP binding transcription factors because it contains a C-terminal PilZ domain which is hypothesized to be the second messenger binding site58.

The last general class of c-di-GMP binding proteins that have been identified to date are degenerate variants of the GGDEF and EAL domain proteins that synthesize and degrade the second messenger (Table 1). These proteins possess mutations to one or more of the conserved active site residues and are no longer catalytically active, but they retain the ability to bind c-di-GMP and instead function as receptors of the second messenger10,12,13,45. Degenerate EAL domain proteins bind c-di-GMP at the active site59,65 whereas degenerate GGDEF proteins bind c-di-GMP at the regulatory I-site61. The I-site effectors are related to the degenerate GGDEF effectors because the c-di-GMP binding site of these proteins is homologous to the I-site, yet the I-site effectors lack a GGDEF site64. The only validated example of an I-site effector to date is the PelD protein from Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which controls PEL polysaccharide synthesis during pellicle formation64. Although sequence analysis can readily predict degenerate GGDEF and EAL domain proteins, the inability of these variants to metabolize c-di-GMP and their specific biological function must be verified experimentally.

Only a few examples of this class of c-di-GMP effectors have been validated. Degenerate GGDEF domain proteins include PopA from Caulobacter crescentus61, CdgG from Vibrio cholerae63, and SmgT from Myxococcus xanthus62. For both PopA and SgmT, c-di-GMP binding induces spatial sequestration of the protein61,62. PopA has been implicated in cell cycle control via c-di-GMP dependent degradation of an inhibitor of replication initiation61 and SgmT is a histidine kinase that phosphorylates DigR, a DNA binding regulator of extracellular matrix production62. However, the functional importance of c-di-GMP dependent sequestration of SgmT is currently unknown. Although the ability of CdgG to bind c-di-GMP has not been confirmed, this protein has no DGC activity yet requires an intact I-site to regulate rugosity, suggesting that second messenger binding is important for its function63. The degenerate EAL domain proteins that have been identified are FimX59 and LapD60 from Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Pseudomonas fluorescens, respectively. FimX and LapD have been shown to control very different processes, with the former important for twitching motility66 and the latter required for biofilm formation60. This demonstrates the diversity of biological phenotypes regulated by these degenerate c-di-GMP metabolizing enzymes.

Collectively, the PilZ domain, degenerate GGDEF/EAL domain proteins, transcription factors, and I-site effectors have affinities for c-di-GMP that range from approximately 50 nM into the low μM range46,48,49,53–55,57,59–61,64. Despite the progress made towards elucidating the downstream targets of this second messenger, the specific mechanisms through which c-di-GMP interacts with many of these proteins to induce a physiological output remain largely obscure. Given the diversity of protein targets already identified, it is likely that additional classes of protein receptors for this second messenger remain to be discovered.

RNA molecules that recognize and bind c-di-GMP

In addition to the proteins that bind c-di-GMP, two classes of riboswitch RNAs, termed class I and class II, have also been identified as part of this second messenger signaling pathway67,68 (Table 1). Riboswitches are non-coding regulatory RNAs consisting of an aptamer domain and expression platform that recognize small molecule ligands with high affinity and specificity (for recent reviews see69–72). Over 20 different riboswitch classes have been identified to date that recognize diverse ligands including amino acids, nucleobases, modified sugars, vitamins and coenzymes, and even small anions. Ligand binding to the aptamer domain causes structural changes in the expression platform that lead to changes in the expression levels of the downstream genes in the absence of any protein cofactors, most often by affecting either transcription or translation. Although riboswitches are now recognized as a major form of bacterial genetic control, the c-di-GMP binding riboswitches represent the first known class of RNAs that directly bind a second messenger signaling molecule and function as a downstream effector in an intracellular signaling pathway67,68.

Approximately 500 examples of class I67 and 45 examples of class II riboswitches68 have been identified throughout the bacterial domain in many different species. In addition, these riboswitches are present in many prominent human pathogens, including the causative agents of anthrax and cholera. Although the use of the class I riboswitch for gene expression is more widespread, several organisms exclusively use the class II riboswitch for signaling, namely those of the class Clostridia68. Consistent with their predicted role in a second messenger signaling pathway, these aptamers are found upstream of a wide collection of genes that regulate cellular processes in which c-di-GMP is now known to play a role, including motility, pilus formation, virulence factor expression, flagellum biosynthesis, and exopolysaccharide matrix production67,68.

The affinities of these riboswitches for c-di-GMP are tighter than for any of the known protein receptors and range from as low as 10 pM for the class I riboswitch73 to between 200 pM and 2 nM for the class II riboswitch68. For the Vc2 class I riboswitch from Vibrio cholerae, it has been demonstrated that the tight binding affinity (10 pM) results from very slow rates of ligand release (kon= 1 x106 M−1 min−1 and koff= 1 x 10−5 min−1)73. Thus, the half life of the c-di-GMP bound complex is approximately 1 month, indicating that ligand binding is effectively irreversible on a biological timescale. Therefore, this riboswitch is thought to be kinetically controlled, where gene regulation is governed entirely by the on-rate and is highly responsive to changing intracellular levels of the second messenger73,74. However, the kinetic properties of other class I riboswitch sequences and that of the class II riboswitch has not been fully explored.

The identification of riboswitches as c-di-GMP receptors is of particular interest because unlike protein effectors, ligand binding is directly coupled to gene regulation, suggesting a mechanism for how c-di-GMP induces a cellular response upon binding this class of effectors. Based upon sequence analysis, transcriptional terminator stems can easily be identified for a subset of class I and class II riboswitches, suggesting that c-di-GMP binding affects the expression levels of downstream genes through a transcriptionally controlled mechanism. However, this has only been experimentally validated for a few riboswitches. One example of a transcriptionally controlled switch is the Cd1 class I riboswitch from Clostridium difficile67. This riboswitch is located upstream of the operon encoding a large subset of the proteins and machinery necessary for flagellum biosynthesis in this organism. In the presence of increasing concentrations of c-di-GMP, transcription is terminated. This is consistent with the observation that high intracellular concentrations of c-di-GMP repress motility. The class II riboswitch encoded by Bacillus halodurans (Bha-1-1) was also determined to be transcriptionally regulated because full length RNA was produced only in the presence of c-di-GMP68.

Translationally controlled riboswitches have also been identified. More specifically, in vivo reporter assays indicated that the Vc2 riboswitch up-regulated expression of the VC1722 gene in the presence of c-di-GMP, while the full-length RNA was transcribed independent of c-di-GMP67. Although the exact function of this gene is unknown, it is hypothesized to be a transcription factor and rugose Vibrio cholerae mutants exhibited elevated levels of this mRNA75. This suggests that increased intracellular levels of c-di-GMP upregulate expression of this protein. These second messenger riboswitches can function as genetic ‘on’ switches, where c-di-GMP binding increases expression levels of the downstream genes, or genetic ‘off’ switches independent of whether they are transcriptionally or translationally controlled67,68.

Structural basis of second messenger recognition

As anticipated from the diversity of its receptor molecules, the specific mechanisms by which this second messenger induces physiological responses are highly variable. In contrast to cAMP and (p)ppGpp, which both act primarily at the transcriptional level through a single protein effector, c-di-GMP acts on protein and RNA targets at the transcriptional, translational, and post-translational levels to alter cellular behavior and physiology3,11,13.

Recognition of c-di-GMP by protein receptors

Given that c-di-GMP plays a regulatory role in many different physiological processes, it was hypothesized that protein receptors of c-di-GMP must also be adaptable to functioning in different biological pathways48. To further investigate how proteins recognize c-di-GMP and how c-di-GMP binding induces different physiological responses mediated through these receptors, the crystal structures of the second messenger in complex with several protein receptors have been solved (Figure 3). Overall, these structures reveal that proteins employ different modes of recognition and can bind the second messenger as a monomer48,59,65,76 or as an intercalated dimer54,76–80. In addition, proteins that recognize c-di-GMP as a monomer can bind the second messenger in either an eclipsed conformation48,76, where the guanine bases are aligned overtop one another, or in an extended conformation where the guanine bases are splayed apart59,65. PilZ domain proteins have been shown to recognize both the monomer and dimer form of c-di-GMP48,76,77, demonstrating that different approaches to second messenger recognition are utilized by effectors of the same class.

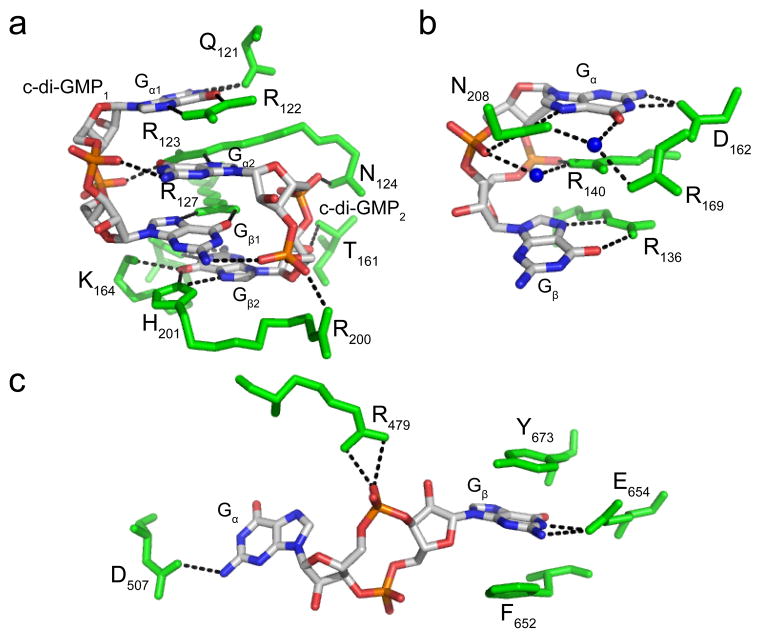

Figure 3.

Protein recognition of c-di-GMP. (a) Recognition by the PilZ domain protein PP4397 from Pseudomonas putida (PDB ID 3KYF). c-di-GMP is colored by atom with carbon shown in white, nitrogen in blue, oxygen in red and phosphorous in orange. Protein residues are colored green and hydrogen bonds are shown as black dashed lines. c-di-GMP is bound as a dimer and the monomeric units are labeled as c-di-GMP1 and c-di-GMP2. The top guanine base of each c-di-GMP monomer is labeled Gα1 or Gα2, depending on which c-di-GMP monomer it belongs to, and the bottom bases are labeled Gβ1 or Gβ2. (b) Recognition by the PilZ domain protein VCA0042 from Vibrio cholerae (PDB ID 2RDE). Each base of the c-di-GMP monomer is arbitrarily labeled Gα or Gβ. Coloring is the same as in part (a) with water molecules shown as blue spheres. (c) Recognition by the degenerate EAL domain protein FimX. Coloring is the same as in part (a) and the guanine bases are arbitrarily labeled as in part (b).

Common c-di-GMP recognition strategies used by proteins include hydrogen bonding contacts with charged or polar side chains and base stacking interactions with aromatic residues. Cation-π interactions are also expected to play a role in recognition as evidenced by charged residues that sometimes stack directly above or below one of the c-di-GMP bases. For proteins that bind c-di-GMP as a dimer, several interactions between the individual c-di-GMP monomers are also observed. The structures of unbound and c-di-GMP bound protein complexes often adopt different conformations. This suggests that ligand-induced conformational changes mediate the specific molecular mechanisms used by these protein effectors to induce biological outputs65,76,77,81,82. However, these c-di-GMP receptors often interact with other proteins to induce a biological output and many of the molecular mechanisms of these downstream interactions remain unknown.

The PilZ domain protein PP4397 from Pseudomonas putida binds the second messenger as an intercalated dimer where both c-di-GMP molecules are in the eclipsed conformation76 (Figure 3a). This allows for base stacking interactions to occur between one guanine base from each monomer, which are arbitrarily termed Gα and Gβ and labeled for each c-di-GMP unit. Recognition of the guanine bases in each individual monomer is asymmetric, however recognition of Gα1 is similar to that of Gβ2, whereas that of Gα2 matches the contacts made to Gβ1. Every atom with hydrogen bonding potential along the Watson-Crick and Hoogsteen faces of Gα1 and Gβ2 is contacted by an RNA atom. In contrast, Gα1 and Gβ2 are only contacted by an arginine residue on their Hoogsteen face. In addition, arginine residues stack with two of the four guanine bases and non-bridging phosphate oxygens hydrogen bond with guanine exocyclic amines or other charged and polar side chains. Overall, recognition of dimeric c-di-GMP by PilZ domain proteins is similar to second messenger recognition and binding by diguanylate cyclases at the inhibitory I-site29,79,80. In contrast, the PilZ domain protein VCA0042 (PDB ID 3KYG) from Vibrio cholerae recognizes c-di-GMP as a monomer in the eclipsed conformation48,76 (Figure 3b). The top base (Gα) is more heavily recognized than the bottom base (Gβ) with contacts made to both its Watson-Crick and Hoogsteen faces. Similar to the base stacking interactions observed for PP4397, an arginine residue also stacks with one of the guanine bases, Gα, in this protein.

While the PilZ domain proteins typically recognize c-di-GMP in the eclipsed conformation, the degenerate EAL domain protein FimX from Pseudomonas aeruginosa binds the second messenger in the extended conformation59 (Figure 3c). Base recognition is achieved primarily through electrostatic interactions with charged side chains and stacking contacts with aromatic residues. Gα is less heavily recognized than Gβ and only one of the c-di-GMP phosphates is contacted. While these c-di-GMP binding proteins utilize similar contacts for recognition, the second messenger binding pockets can be quite diverse.

Recognition of c-di-GMP by riboswitches

The identification of c-di-GMP binding riboswitches defines a new role for RNA as part of a second messenger signaling pathway. To understand the molecular basis of RNA recognition of c-di-GMP, the crystal structures of the second messenger bound to the aptamer domains of both the class I and class II riboswitch were determined by our laboratory and others73,83–85 (Figure 4). As anticipated from secondary structure analysis, these RNAs adopt unique conformations and employ different strategies for ligand recognition. The class I riboswitch adopts a y-shape with c-di-GMP bound at the three helix junction incorporated as part of a duplex73,83, whereas class II folds into a more compact structure and incorporates the second messenger into a triplex at the edge of the pseudoknot region85. The ability of these riboswitches to incorporate the second messenger into the RNA structure likely contributes to the tighter binding affinities for these effectors as compared to protein receptors.

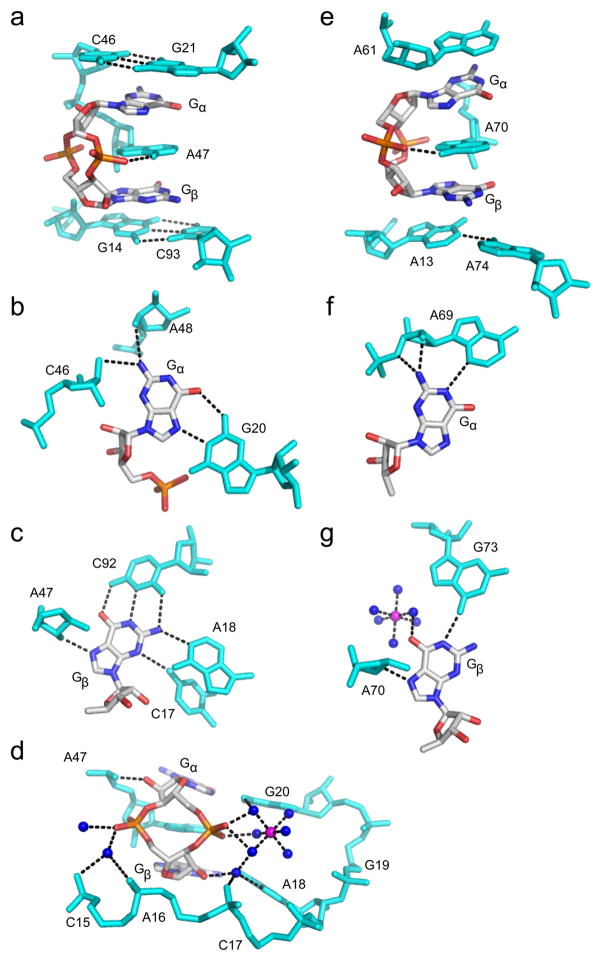

Figure 4.

RNA recognition of c-di-GMP. c-di-GMP is colored by atom as in Figure 3. RNA residues are colored cyan, water molecules are shown as blue spheres and magnesium ions as magenta spheres. Hydrogen bonds are indicated by black dashed lines. (a) c-di-GMP bound to the Vc2 class I riboswitch from Vibrio cholerae (PDB ID 3MXH). (b) Recognition of Gα,(c) Gβ and (d) the c-di-GMP ribosyl-phosphate backbone by the class I riboswitch. (e) c-di-GMP bound to the Cac-1-2 class II ribowitch from Clostridium acetobutylicum (PDB ID 3Q3Z). (f) Recognition of Gα and (g) Gβ by the class II riboswitch.

In the class I riboswitch, c-di-GMP binds at the three helix junction formed by P1, P2, and P3 with contacts to the ligand made by three critical nucleotides (G20, C92, and A47)83. The guanine bases, arbitrarily termed Gα and Gβ are recognized asymmetrically in canonical pairings, with Gα forming a Hoogsteen pair with G20 and Gβ in a Watson-Crick pair with C92 (Figure 4b,c). Stacking between the two guanine bases is a highly conserved adenosine (A47) that serves to bridge the P1 and P2 helices with the c-di-GMP ligand resulting in extensive base stacking interactions (Figure 4a). The ribosyl-phosphate backbone is also extensively contacted, with recognition mediated by both hydrogen bonding and metal-phosphate contacts (Figure 4d).

In contrast to recognition by the class I riboswitch, the class II riboswitch also recognizes the guanine bases of c-di-GMP asymmetrically, however no canonical base pairings are observed and in general, fewer base contacts to the bases are made by binding pocket nucleotides85 (Figure 4f, g). Instead, Gα is recognized as part of a base triple with A69 and U37, and Gβ is contacted by hydrogen bonds from RNA residues A70 and G73, as well as by a hydrated magnesium. Three conserved adenosine nucleotides that stack between (A70), above (A61) and below (A13) the bases of c-di-GMP indicate that base stacking is also important for ligand binding (Figure 4e).

Between the two riboswitches, there are four different solutions to guanine recognition by the RNA aptamer83,85 (Figure 4b,c,f,g). Stacking interactions are the only parallels in ligand recognition between the two riboswitch classes85 (Figure 4a,e). Minimal contacts are made to the ribosyl-phosphate backbone by the class II riboswitch with only a single hydrogen bond observed to one non-bridging phosphate oxygen (Figure 4e). It is clear that at least two independent molecular solutions for RNA recognition of the same second messenger ligand exist.

The mechanisms evolved for c-di-GMP recognition by RNA differ significantly from those utilized by protein receptors. Unlike proteins, RNA is able to incorporate the second messenger into structural elements, which likely contributes to the tight binding affinities observed for this class of receptors83,85. While both proteins and RNA employ stacking as a mechanism for second messenger binding, the stacking interactions made between the guanine bases of c-di-GMP and purine residues in the riboswitch binding pocket appear to be more extensive than those made with aromatic side chains of proteins. Although, the specific contacts made by the class I and class II riboswitches to c-di-GMP greatly differ, the ligand is bound in the same eclipsed conformation. This is in contrast to proteins, which can bind c-di-GMP in many different conformations, suggesting that the eclipsed conformation is functionally relevant for RNA recognition. Collectively, these observations indicate that the diverse receptors of c-di-GMP also employ diverse mechanisms for second messenger recognition and binding.

Chemical tools to study and target the c-di-GMP signaling pathway: Synthesis of c-di-GMP and second messenger analogs

c-di-GMP is used by many prominent human pathogens to control biological processes and the lack of this second messenger in eukaryotes suggests that, c-di-GMP binding partners could be attractive new targets for the development of therapeutics against bacterial infection. Thus, the ability to synthesize c-di-GMP and second messenger analogs is useful for increasing our understanding of how macromolecular effectors recognize c-di-GMP and how to effectively design second messenger analogs to target the c-di-GMP receptors that function downstream in this signaling pathway. Towards this goal, several groups have developed chemical methods for synthesizing cyclic dinucleotide analogs of the second messenger. Many of these synthetic efforts have been undertaken with the ultimate goal of using these molecules to manipulate the biological processes regulated by c-di-GMP through the selective modulation of RNA and protein second messenger binding partners.

Chemical synthesis of c-di-GMP and nucleotide analogs of the second messenger

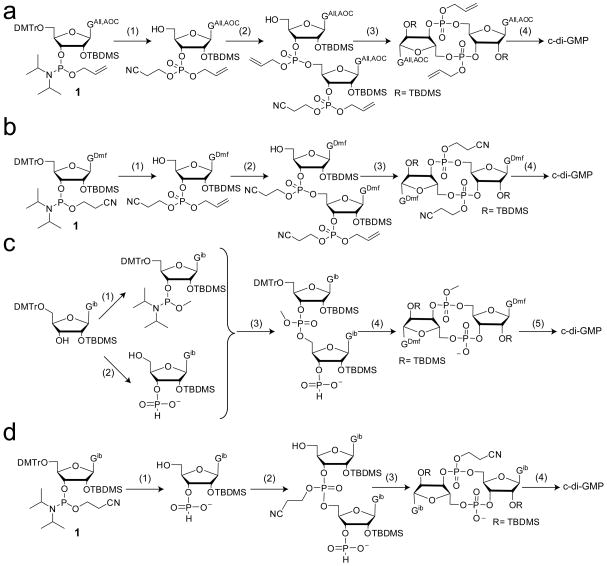

The first chemical method for synthesizing c-di-GMP was reported in 1990 by the laboratories of Benziman and van Boom86. This method utilized phosphotriester chemistry to access c-di-GMP via the linear dinucleotide GpGp. Although producing pure c-di-GMP, this strategy suffered from low product yields due to difficulty in efficiently synthesizing the GpGp intermediate as well as product degradation upon multiple deprotection steps, some which required the use of harsh basic conditions86,87. Since then, and mostly in the past decade, several novel synthetic strategies have been developed that produce c-di-GMP in greater yields and can also be utilized to synthesize derivatives of the second messenger.

Hayakawa et al. utilized a phosphoramidite approach to make the linear dinucleotide GpGp intermediate, which overcomes the limitations of the first chemical method for c-di-GMP production87 (Figure 5a). Using allyl-based protecting groups (allyl= All; alloxycarbonyl= AOC) on the phosphate and guanine base of the starting phosphoramidite monomer, oxidation in the presence of 2-cyanoethanol yielded the fully protected guanosine phosphate derivative. After 5′-deprotection, this building block was condensed with a second guanosine phosphoramidite monomer, producing the linear intermediate GpGp in much higher yield than previously observed86. This intermediate was then directly used in the cyclization reaction. Use of allyl protecting groups for both the guanine bases and the phosphates allowed for deprotection in a single step under much milder conditions, resulting in overall increased product yield. Hyodo and Hakayawa further improved this method by utilizing a guanosine phosphoramidite building block with different base and phosphate protecting groups88 (Figure 5b). By employing a dimethylformamide (dmf) group for protection of the guanine exocyclic amine while leaving the O6 unprotected the starting phosphoramidite monomer could be synthesized in fewer steps. In addition, the phosphate moiety was protected with a cyanoethyl group and then oxidized in the presence of allyl alcohol. After condensation to form the GpGp intermediate, the allyl group, was selectively removed prior to cyclization, leaving only the dimethylformamide and cyanoethyl protecting groups to be removed after cyclization, which could be accomplished in a single step88. Modification to the synthesis of the guanosine phosphoramidite monomer proved to increase overall yields beyond that of the first generation method. Furthermore, this method was readily adapted to afford base modified second messenger analogs containing a single inosine or adenine base in place of one guanine by using the appropriate base protecting groups compatible with the deprotection conditions for the dmf group89. A single phosphorothioate analog was also obtained using this method by replacing the oxidation reagent with a sulfurization reagent for one oxidation step.

Figure 5.

Solution phase methods for c-di-GMP synthesis. (a) First phosphoramidte method developed by Hayakawa et al87. 1) i) 2-cyanoethanol, IMP, ACN ii) 2-butanone peroxide (BPO)/toluene iii) DCA/DCM; 2) i) 1, IMP, ACN ii) BPO/toluene iii) DCA/DCM; 3) i) NH3-MeOH ii) TPSCl, N-methylimidazole, THF; 4) i) palladium catalyst, triphenylphosphine, butylammonium formate, THF ii) HF-TEA. (b) Improved phosphoramidite method88. Phosphoramidite 1 is synthesized in higher yield and few steps than that used in Scheme (a). 1) i) allyl alcohol, IMP, ACN ii) BPO/toluene iii) DCA/DCM; 2) i) 1, IMP, ACN ii) BPO/toluene iii) DCA/DCM; 3) i) NaI, acetone ii) TPSCl, N-methylimidazole; 4) i) NH3-MeOH ii) HF-TEA. (c) Method developed by the Jones group90. c-di-GMP is synthesized using phosphoramidite coupling and H-phosphonate cyclization. 1) Bis(diisopropylamino)methyl phosphoramidite and pyridinium trifluoroacetate; 2) 2-chloro-4H-1,3,2-benzodioxaphosphorin-4-one; 3) i) pyridinium trifluoroacetetate ii) tert-butylhydroperoxide; 4) i) sulfonic acid resin ii) adamantoylcarbonyl chloride iii) methanol/NBS; 5) i) pyridine/ aq. NH3 ii) HF-TEA. (d) Synthesis of c-di-GMP in one pot95,96. 1) i) pyr·TFA/H2O ii) tBuNH2 iii) DCA/H2O 2) i) pyridine/1 ii) tBuOOH iii) DCA/H2O 3) i) DMOCP ii) I2/H2O 4) i) tBuNH2 ii) TEA·HF. For synthesis of dithiophosphate analogs, tBuOOH was replaced with the sulfurization reagent 3-((dimethylamino-methylidene)amino)-3H-1,2-benzodithiol-3-one in the first oxidation step and I2/H2O was replaced with 3-H-1,2-benzodithiol-3-one in the second oxidation step95.

A modified version of the phosphoramidite approaches described above using an H-phosphonate cyclization procedure was developed by the Jones group90, providing yet another synthetic route for accessing c-di-GMP (Figure 5c). In this method, the 5′-DMTr, 2′-TBDMS, N2-isobutyrl protected guanosine was converted to both the methyl-phosphoramidite and H-phosphonate, which were then coupled together. The H-phosphonate serves as a protecting group in the coupling step, yielding only a single GpGp intermediate and eliminating additional protection and deprotection steps that were necessary for the previously developed methods. After 5′-detritylation, cyclization is catalyzed by the addition of adamantoyl chloride followed by the final oxidation step to give the fully protected cyclic dinucleotide. This method is advantageous over the previously used strategies due to the elimination of several protection/deprotection steps, resulting in fewer synthetic steps overall.

In addition to the solution phase syntheses discussed above, two additional synthetic methodologies have also been developed that have proven to be useful for accessing c-di-GMP and its analogs. The first method, developed by Amiot et al., employs a novel strategy of glycosylation of a glycan precursor91. In this method, the glycan precursor first synthesized is the cyclized ribosyl-phosphate backbone absent any base structure. Glycosylation of this intermediate introduces the desired base to produce the cyclic dinucleotide molecule. The second strategy, developed by Yan et al., utilizes a modified H-phosphonate approach along with the 1-(4-chlorophenyl)-4-ethoxypiperidin-4-yl (Cpep) group for protection of the ribose 2′-hydroxyl functionality92. Both methods have been demonstrated to yield pure c-di-GMP in good yield.

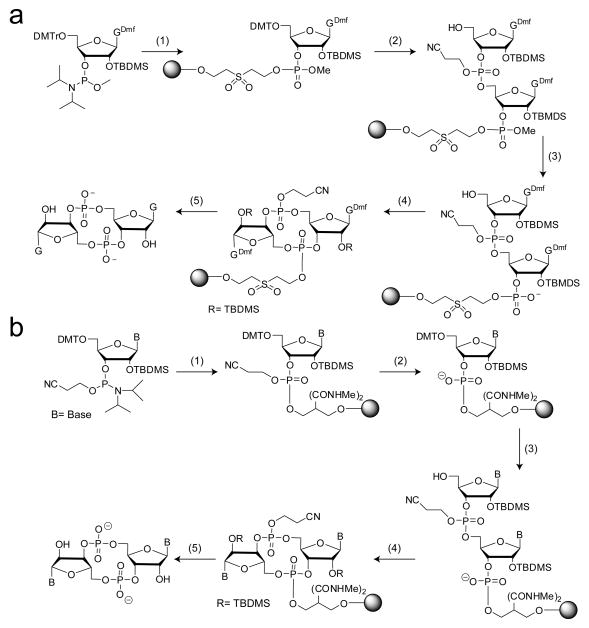

All the aforementioned c-di-GMP synthetic strategies are solution phase methods and therefore require the purification of various intermediates before formation of the final product. To further simplify the synthesis of c-di-GMP, Kiburu et al. developed a simple solid-phase synthesis for this second messenger that required purification of only the final, fully deprotected product93 (Figure 6a). The authors used two different approaches: one in which the linear dinucleotide was cyclized on the solid support (Figure 6a) and a second in which the linear intermediate was cleaved from the solid support and cyclization was performed in solution. For on-bead cyclization, the 5′-DMTr, 2′-TBDMS, O-methyl guanosine phosphoramidite was coupled to the solid support followed by oxidation and 5′-detritylation. For the second coupling, the more commonly available cyanoethyl-phosphate protected phosphoramidite was used. This allowed for the selective deprotection of the methyl group, providing only one free phosphate oxygen for the subsequent cyclization reaction. Following cyclization, the cyclic dimer was cleaved from the bead, deprotected and purified by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (Figure 6a). In contrast, the solution cyclization method used O-methyl phosphoramidites for both coupling steps. Because the O-methyl group is inert to β-elimination, triethylamine can be used to cleave the linear dinucleotide from the solid support without removing any protecting groups that are necessary for successful cyclization. The development of this solid-phase approach for c-di-GMP synthesis was a great advancement because naturally occurring bases are available as O-methyl phosphoramidites, allowing several dinucleotide analogs to easily be synthesized using this approach.

Figure 6.

Solid phase methods for c-di-GMP synthesis utilizing on-bead cyclization procedures. (a) Method developed by Kiburu et al93. Two different phosphoramidites containing different phosphate protecting groups were used. 1) i) solid support, tetrazole/ACN ii) I2, pyridine, H2O; 2) i) DCA/DCM ii) cyanoethyl phosphoramidite, tetrazole/ACN iii) I2 pyridine, H2O iv) DCA/DCM; 3) S2Na2 4) MSNT, pyridine 5) i) aqueous NH3 ii) HF-TEA. For the solution phase cyclization method, O-methyl phosphoramidtes were used in both coupling steps and the linear dinucleotide was cleaved from the bead prior to cyclization and global deprotection. (b) Modified solid-phase synthesis of c-di-GMP, base and ribose modified analogs. Cyanoethyl-protected phosphoramidites were used for both coupling reactions. 1) i) tetrazole/ACN ii) tBuOOH iii) acetic anhydride/methylamine; 2) i) 50% TEA/ACN, 2 hours; 3) i) 3% DCA/DCM ii) tetrazole/ACN + CNE phosphoramidite iii) tBuOOH iv) acetic anhydride/methylamine 4) 0.1M MSNT, 72–96 hours; 5) i) ammonium hydroxide ii) HF-TEA (for 2′-OH analogs only).

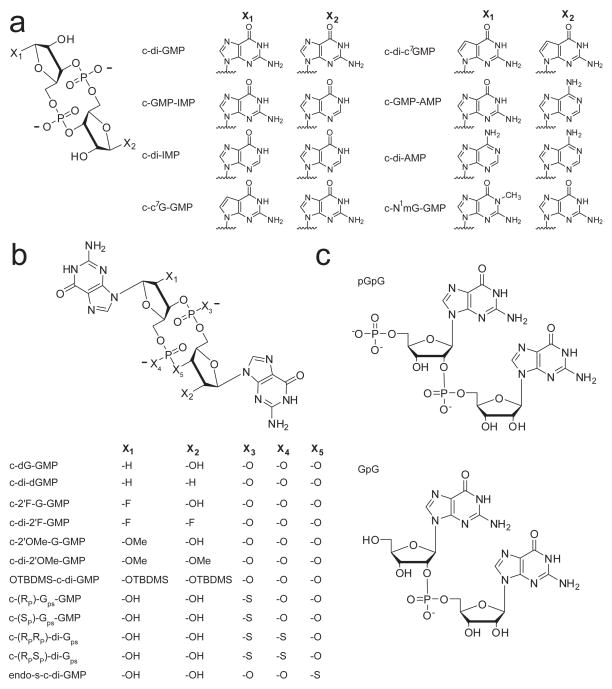

Our lab has further modified this solid-phase synthetic approach such that the most common, commercially available starting phosphoramidites employing a 5′-DMTr, 2′-OTBDMS, and cyanoethyl phosphate protecting groups could be used for both coupling steps94 (Figure 6b). Phosphoramidites were coupled to a solid support that is inert to β-elimination under mild basic conditions. This allowed us to introduce a phosphate deprotection step after the first coupling step, providing the free phosphate oxygen for subsequent cyclization, without cleaving the nucleotide from the bead. After the second coupling reaction, cyclization was carried out on bead. Using this approach, we successfully synthesized novel base and ribose modified second messenger analogs, including 2′-fluoro, 2′-methoxy, 7-deaza guanine, and N1-methyl guanosine derivatives in addition to others previously synthesized by different methods (inosine, adenosine, and 2′-deoxy), in reasonable yield for biochemical experiments (Figure 7a,b).

Figure 7.

Structures of chemically synthesized dinucleotide second messenger analogs used to probe protein and RNA c-di-GMP effector molecules. (a) Cyclic analogs containing base modifications and (b) ribosyl-phosphate backbone modifications. (c) Linear dinucleotide analogs.

The ability to synthesize the second messenger and its derivatives on a large scale at low cost is necessary for biological studies aimed at further elucidating its molecular mechanisms of action and the development of high yielding synthetic procedures is a continuing aim. Towards this goal, the Jones group recently reported a synthesis of c-di-GMP and its phosphorothioate analogs that yields gram-scale quantities of these compounds via eight steps in a single flask95,96 (Figure 5d). The phosphoramidite and H-phosphonate approaches are combined as previously reported90, however the reagents for each synthetic step are compatible with those used for subsequent steps, including the removal of all protecting groups. In addition, pure c-di-GMP can be isolated by crystallization, eliminating the need for column purification of reaction intermediates or the final product. Phosphorothioate derivatives of c-di-GMP were also successfully synthesized by this method using a sulfurization reagent in place of the oxidation reagent and column purification of these compounds was only necessary to separate the different diastereomers95. Adapting this method for the synthesis of other c-di-GMP analogs is expected to allow for the production of these derivatives in large enough yield to perform biological studies and probe second messenger signaling in vivo.

Targeting c-di-GMP binding proteins with second messenger analogs

The ability to selectively bind protein receptors could be a useful strategy for altering bacterial behavior and developing compounds with anti-biofilm or anti-virulence activity97. Although the targeting of c-di-GMP binding proteins with second messenger analogs has not been as extensively explored as it has for riboswitch effectors (discussed below), one general paradigm that has emerged from efforts to design c-di-GMP derivatives that target protein receptors is the use of conformational biasing. c-di-GMP can exist in primarily two conformations, the open state where the guanine bases are splayed apart or the closed state where the guanine bases are aligned over top one another in an anti-parallel fashion, and different protein receptors of the second messenger recognize different conformations (discussed above). This observation has been exploited by the Sintim group to selectively target c-di-GMP binding proteins that recognize only one conformation of the second messenger using an analog with an altered conformer population relative to that of the native second messenger97.

The Sintim group replaced one of the bridging oxygens of a single c-di-GMP phosphate linkage with sulfur and demonstrated both computationally and experimentally that the resulting analog, termed endo-S-c-di-GMP, favored the open conformation in solution and was three times less likely than c-di-GMP to populate the closed conformation97 (Figure 7b). This analog was not able to bind the PilZ domain protein Alg44 from Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which recognizes c-di-GMP as two intercalating dimers, both in the closed conformation, nor inhibit c-di-GMP synthesis of the DGC WspR, which binds c-di-GMP at the inhibitory I-site in the same fashion97. However, this compound was able to bind and inhibit c-di-GMP degradation by the EAL domain protein RocR, which binds c-di-GMP in the open conformation97. This suggests that conformational biasing may be a general strategy for designing second messenger analogs that target one class of binding proteins based on the oligomeric state in which they recognize c-di-GMP.

Targeting c-di-GMP binding riboswitches with second messenger analogs

Our lab has also completed a structure-activity relationship for c-di-GMP binding to both the class I and class II riboswitches using base, ribose, and phosphate modified analogs (Figure 7a,b) to determine the structural features of the second messenger most important for recognition94. This has provided insights into how to design c-di-GMP analogs that can bind these regulatory RNAs and potentially be used to manipulate the biological processes under control of these riboswitches. These studies have revealed that the class I riboswitch is much more discriminatory in second messenger recognition than the class II riboswitch and utilizes nearly every structural feature of c-di-GMP for binding and recognition. In contrast, the class II riboswitch can accommodate many structural analogs of guanine into the binding pocket that the class I riboswitch either completely discriminated against or bound with a significantly weaker affinity compared to the native ligand. Furthermore, the class II riboswitch does not absolutely require the ribosyl-phosphate backbone for second messenger recognition. This lack of backbone recognition has been further confirmed by a binding study using a biotinylated version of c-di-GMP that demonstrated the class II riboswitch was highly tolerant to this bulky modification at the 2′-OH position of the ribose rings98.

The lack of c-di-GMP ribosyl-phosphate backbone recognition by the class II riboswitch lends this class of c-di-GMP receptors to be selectively targeted over the class I riboswitch. This could be a useful strategy for manipulating specific biological processes under control of the class II riboswitch without affecting processes regulated by the class I riboswitch. Taking advantage of the minimal contacts made to the ribosyl-phosphate backbone of c-di-GMP by the class II riboswitch, we demonstrated that a doubly modified 2′-O-methyl second messenger analog showed a 10,000-fold binding preference for this riboswitch over class I85 (c-di-2′-OMe-GMP, Figure 7b). In addition, another study demonstrated that a 2′-OTBDMS version of c-di-GMP bound the class II RNA with an affinity only 50-fold weaker than that of the native second messenger99 (Figure 7b). While this further demonstrates the tolerance of this RNA towards ribose modification, introduction of such large hydrophobic groups has the potential to increase the cell permeability of the second messenger, which is necessary for in vivo studies. Other analogs that also showed a greater than 100-fold binding preference for the class II riboswitch and still bound tightly to this regulatory RNA included c-di-IMP, c-di-dGMP, and c-(RPSP)-di-Gps94 (Figure 7a,b). This also underscores the observation that the class II riboswitch is tolerant to modification of the bases, ribose rings and phosphate linkages of c-di-GMP, whereas the class I riboswitch extensively utilizes all of these structural features of the second messenger for recognition and is much less tolerant of the same ligand perturbations94.

One of the only similarities in second messenger recognition noted from structural analysis among the class I and class II riboswitches is the extensive base stacking interactions made between the guanine bases of the ligand and conserved binding pocket nucleotides85 (Figure 4a,e). Analog binding studies have further confirmed the importance of base stacking in ligand recognition, suggesting general principles for the design of second messenger analogs to target these c-di-GMP binding aptamers. Binding of 7-deaza guanine modified ligands to c-di-GMP riboswitches revealed that a much larger cost to the binding energy is observed for this modification than would be predicted from eliminating only the observed hydrogen bonding contacts to the N7 position in the crystal structure 94 (c-c7GMP-GMP and c-di-c7GMP, Figure 7a). These data were interpreted as a stacking effect based on the observation that nucleic acid duplexes containing 7-deaza guanine are less stable than the corresponding duplexes containing the native guanine base due to decreased base pairing and base stacking interactions100. This suggests that the extensive base stacking contacts made in the aptamer binding pocket are also being perturbed by this modification to c-di-GMP, contributing to the large loss in binding energy. To maintain these base stacking contacts, c-di-GMP must be bound in the closed conformation, suggesting that analogs populating the open conformation may be discriminated against by these RNA receptors. Consistent with these observations, it has also been demonstrated that the c-di-GMP analog favoring the open conformation, endo-S-c-di-GMP (introduced above) (Figure 7b), has a weaker affinity for both the class I and class II riboswitches compared to the native second messenger98. No contacts are made to the bridging phosphate oxygens by either riboswitch and replacing this atom with sulfur should not perturb any contacts, suggesting that the loss in affinity is due to a loss of efficient stacking. This is further supported by the observation that sulfur substitution of non-bridging phosphate oxygens has almost no effect on ligand binding by the class II riboswitch94, whereas the equally conservative modification of substituting a bridging phosphate oxygen with sulfur, which affects the conformation of the second messenger, has a much greater effect on ligand binding98.

All of the strategies for targeting c-di-GMP binding riboswitches discussed above utilize cyclic derivatives of the second messenger. Recently, Breaker and coworkers explored the utility of using linear dinucleotide analogs to target these second messenger riboswitches99 (Figure 7c). The advantage of designing linear analogues over cyclic analogues to target these second messenger riboswitches is that they are synthetically much easier to access99. Both RNA aptamers show a large preference for binding the cyclic dinucleotide over the linear dinucleotide (pGpG, Figure 7c), approximately 5 orders of magnitude for the class I riboswitch67,101 and 3 orders for class II68. Despite this fact, several linear modified derivatives bound reasonably well to these RNAs. However, the tightest binding linear analog for both riboswitches proved to be the natural c-di-GMP breakdown product, pGpG99. Interestingly, removal of the terminal 5′-phosphate to yield GpG did not significantly affect the affinity for the class I riboswitch relative to pGpG99,101 (Figure 7c). In contrast, slightly improved affinity for the class II riboswitch was observed if the terminal 5′-phosphate on the linear dinucleotide analogs was retained99. Structural studies from our group have revealed that pGpG can only bind the class I aptamer in a single orientation with the terminal 5′-phosphate placed 5′ of Gα in close proximity to G20, whereas GpG can bind in two different orientation with no preference for the placement of the linking phosphate101. This is likely due to potential steric and electrostatic clashes that may occur between the terminal 5′-phosphate and RNA atoms when placed at alternative positions. In addition, many of the metal-phosphate and metal-RNA contacts observed for c-di-GMP are lost in binding pGpG. Thus, if the molecule is not cyclic, there is little to no advantage in maintaining a 5′-phosphate101. Taken together, this suggests that cyclic versions of the second messenger are more effective at targeting c-di-GMP riboswitches over linear analogues, despite the ease of synthesis in obtaining the latter.

Several studies have reported that the exogenous addition of c-di-GMP and several of its second messenger analogs to bacteria induces biological phenotypes, specifically a decrease in biofilm formation102–105. While the mechanism of action of these compounds is unknown, it has been hypothesized that these second messenger derivatives enter cells and act intracellularly on known c-di-GMP target molecules. Thus, it will be interesting to see if these compounds modulate bacterial behavior through interactions with c-di-GMP RNA and protein effectors and if it is possible to design analogs that induce different phenotypic effects.

Conclusions and Perspectives

The ubiquitous bacterial second messenger signaling molecule c-di-GMP controls a variety of biological processes including biofilm formation, virulence response, and motility. The absence of this small molecule in eukaryotes makes this pathway an attractive target for the development of new antibacterial drugs that would not kill the cells but instead modulate the virulence and biofilm forming behaviors of the microbe. In addition, we are far from a complete mechanistic understanding of c-di-GMP signaling pathways. Thus, the development of c-di-GMP analogs as chemical tools to study interactions of the second messenger with its targets needs to be further explored because these studies will guide the design of compounds with potential therapeutic efficacy. .

Designing c-di-GMP analogs that tightly bind second messenger targets but simultaneously incorporate modifications that impart desirable properties for in vivo studies, such as increased cell permeability and increased resistance to enzymatic degradation, is a desirable goal. However, what remains a constant challenge is the development of more efficient and higher yielding synthetic routes to obtain modified versions of the second messenger. Given the complexity of c-di-GMP signaling and the steady emergence of new protein and RNA binding partners of the second messenger, chemical tools to isolate new effector molecules would also be valuable. Towards this aim, a biotinylated version of the second messenger has been employed to isolate c-di-GMP binding proteins106, however the placement of the biotin moiety inhibits binding to certain targets98. Thus, an array of analogs with chemical handles at different positions on c-di-GMP could be useful for identifying new targets with unique modes of second messenger recognition.

Furthermore, it will be necessary to explore the biological consequences of targeting c-di-GMP binding proteins and RNA in vivo with second messenger analogs. Multiple c-di-GMP targets often exist within a single organism and identifying analogs that selectively target proteins over RNA and vice versa will be necessary to disentangle signaling events that are mediated by these diverse macromolecular effectors. It is currently unknown if it is possible to achieve selectivity for one particular target within the complex environment of the cell. Identification of second messenger analogs that induce interesting phenotypic effects and have behavioral responses in bacteria, as well as elucidating the molecular mechanisms of action of such bioactive compounds, will continue to be an active area of research.

Acknowledgments

We thank K. Smith for critical comments on this manuscript.

References

- 1.Galperin MY. Environ Microbiol. 2004;6:552–567. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2004.00633.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Camilli A, Bassler BL. Science. 2006;311:1113–1116. doi: 10.1126/science.1121357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pesavento C, Hengge R. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2009;12:170–176. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McDonough KA, Rodriguez A. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2012;10:27–38. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Magnusson LU, Farewell A, Nyström T. Trends Microbiol. 2005;13:236–242. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Potrykus K, Cashel M. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2008;62:35–51. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.162903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gomelsky M. Mol Microbiol. 2011;79:562–565. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07514.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jenal U. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2004;7:185–191. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2004.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Römling U, Gomelsky M, Galperin MY. Mol Microbiol. 2005;57:629–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hengge R. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:263–273. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schirmer T, Jenal U. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:724–735. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mills E, Pultz IS, Kulasekara HD, Miller SI. Cell Microbiol. 2011;13:1122–1129. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2011.01619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sondermann H, Shikuma NJ, Yildiz FH. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2012;15:140–146. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2011.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jenal U, Malone J. Annu Rev Genet. 2006;40:385–407. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.40.110405.090423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oppenheimer-Shaanan Y, Wexselblatt E, Katzhendler J, Yavin E, Ben-Yehuda S. EMBO Rep. 2011;12:594–601. doi: 10.1038/embor.2011.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Corrigan RM, Abbott JC, Burhenne H, Kaever V, Gründling A. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002217. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ross P, et al. Nature. 1987;325:279–281. doi: 10.1038/325279a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tal R, et al. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4416–4425. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.17.4416-4425.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galperin MY, Nikolskaya AN, Koonin EV. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2001;203:11–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.D’Argenio DA, Miller SI. Microbiol. 2004;150:2497–2502. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27099-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ryjenkov DA, Tarutina M, Moskvin OV, Gomelsky M. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:1792–1798. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.5.1792-1798.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paul R, Weiser S, Amiot NC, Chan C, Schirmer T, Giese B, Jenal U. Genes Dev. 2004;18:715–727. doi: 10.1101/gad.289504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmidt AJ, Ryjenkov DA, Gomelsky M. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:4774–4781. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.14.4774-4781.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tamayo R, Tischler AD, Camilli A. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:33324–33330. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506500200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rao F, Yang Y, Qi Y, Liang Z-X. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:3622–3631. doi: 10.1128/JB.00165-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Galperin MY, Natale DA, Aravind L, Koonin EV. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 1999;1:303–305. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ryan RP, Fouhy Y, Lucey JF, Crossman LC, Spiro S, He Y, Zhang L, Heeb S, Camara M, Williams P, Dow JM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:6712–6717. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600345103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 28.Christen B, Christen M, Folcher M, Schauerte A, Jenal U. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:32015–32024. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603589200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chan C, Paul R, Samoray D, Amiot NC, Giese B, Jenal U. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:17084–17089. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406134101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tamayo R, Pratt JT, Camilli A. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2007;61:131–148. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simm R, Morr M, Kader A, Nimtz M, Römling U. Mol Microbiol. 2004;53:1123–1134. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tischler AD, Camilli A. Infect Immun. 2005;73:5873–5882. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.9.5873-5882.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ahmad I, Lamprokostopoulou A, Le Guyon S, Streck E, Barthel M, Peters V, Hardt W, Romling U. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e28351. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pitzer JE, Sultan SZ, Hayakawa Y, Hobbs G, Miller MR, Motaleb MA. Infect Immun. 2011;79:1815–1825. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00075-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Waters CM, Lu W, Rabinowitz JD, Bassler BL. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:2527–2536. doi: 10.1128/JB.01756-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Srivastava D, Waters CM. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:4485–4493. doi: 10.1128/JB.00379-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fong JCN, Yildiz FH. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:6646–6659. doi: 10.1128/JB.00466-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beyhan S, Bilecen K, Salama SR, Casper-Lindley C, Yildiz FH. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:388–402. doi: 10.1128/JB.00981-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Christen M, Christen B, Folcher M, Schauerte A, Jenal U. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:30829–30837. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504429200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seshasayee ASN, Fraser GM, Luscombe NM. Nucl Acids Res. 2010;38:5970–5981. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tarutina M, Ryjenkov DA, Gomelsky M. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:34751–34758. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604819200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ferreira RBR, Antunes LCM, Greenberg EP, McCarter LL. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:851–860. doi: 10.1128/JB.01462-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ryan RP, Fouhy Y, Lucey JF, Dow JM. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:8327–8334. doi: 10.1128/JB.01079-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sommerfeldt N, Possling A, Becker G, Pesavento C, Tschowri N, Hengge R. Microbiol. 2009;155:1318–1331. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.024257-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krasteva PV, Giglio KM, Sondermann H. Protein Sci. 2012;21:929–948. doi: 10.1002/pro.2093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Amikam D, Galperin MY. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:3–6. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ryjenkov DA, Simm R, Römling U, Gomelsky M. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:30310–30314. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600179200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Benach J, Swaminathan SS, Tamayo R, Handelman SK, Folta-Stogniew E, Ramos JE, Forouhar F, Neely H, Seetharaman J, Camilli A, Hunt JF. EMBO J. 2006;26:5153–5166. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pratt JT, Tamayo R, Tischler AD, Camilli A. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:12860–12870. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611593200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boehm A, Kaiser M, Li H, Spangler C, Kasper CA, Ackermann M, Kaever V, Sourjik V, Roth V, Jenal U. Cell. 2010;141:107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Paul K, Nieto V, Carlquist WC, Blair DF, Harshey RM. Mol Cell. 2010;38:128–139. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Merighi M, Lee VT, Hyodo M, Hayakawa Y, Lory S. Mol Microbiol. 2007;65:876–895. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05817.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hickman JW, Harwood CS. Mol Microbiol. 2008;69:376–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06281.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Krasteva PV, Fong JC, Shikuma NJ, Beyhan S, Navarro MV, Yildiz FH, Sondermann H. Science. 2010;327:866–868. doi: 10.1126/science.1181185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Leduc JL, Roberts GP. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:7121–7122. doi: 10.1128/JB.00845-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tao F, He Y-W, Wu D-H, Swarup S, Zhang L-H. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:1020–1029. doi: 10.1128/JB.01253-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Srivastava D, Harris RC, Waters CM. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:6331–6341. doi: 10.1128/JB.05167-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wilksch JJ, Yang J, Clements A, Gabbe JL, Short KR, Cao H, Cavaliere R, James CE, Whitchurch CB, Schembri MA, Chuah ML, Liang Z-X, Wijburg OL, Jenney AW, Lithgow T, Strugnell RA. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002204. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Navarro MVAS, De N, Bae N, Wang Q, Sondermann H. Structure. 2009;17:1104–1116. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Newell PD, Monds RD, O’Toole GA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:3461–3466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808933106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Duerig A, Abel S, Folcher M, Nicollier M, Schwede T, Amiot N, Giese B, Jenal U. Genes Dev. 2009;23:93–104. doi: 10.1101/gad.502409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Petters T, Zhang X, Nesper J, Treuner-Lange A, Gomez-Santos N, Hoppert M, Jenal U, Soggard-Andersen L. Mol Microbiol. 2012;84:147–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08015.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Beyhan S, Odell LS, Yildiz FH. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:7392–7405. doi: 10.1128/JB.00564-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lee VT, Matewish JM, Kessler JL, Hyodo M, Hayakawa Y, Lory S. Mol Microbiol. 2007;65:1474–1484. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05879.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Navarro MVAS, Newell PD, Krasteva PV, Chatterjee D, Madden DR, O’Toole GA, Sondermann H. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1000588. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kazmierczak BI, Lebron MB, Murray TS. Mol Microbiol. 2006;60:1026–1043. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05156.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sudarsan N, Lee ER, Weinberg Z, Moy RH, Kim JN, Link KH, Breaker RR. Science. 2008;321:411–413. doi: 10.1126/science.1159519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lee ER, Baker JL, Weinberg Z, Sudarsan N, Breaker RR. Science. 2010;329:845–848. doi: 10.1126/science.1190713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Montange RK, Batey RT. Annu Rev Biophys. 2008;37:117–133. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.130000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Roth A, Breaker RR. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:305–334. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.070507.135656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]