Abstract

Objective

To compare outcomes following osteocutaneous radial forearm and fibula free flap reconstruction of lateral mandibular defects.

Study Design

Retrospective case controlled study.

Setting

Two academic tertiary care centers.

Subjects and Methods

Patients who underwent free flap reconstruction of lateral mandibular defects from 1999 to 2010 were classified into four groups based on type of reconstruction: 1) radial forearm swing (n = 8), 2) radial forearm with bar (n = 5), 3) osteocutaneous radial forearm (n = 73) and 4) fibula free flap reconstruction (n = 51). Patient characteristics, length of hospital stay, recipient and donor site complications, and long term outcomes including postoperative diet were evaluated.

Results

The majority of patients were male (67%) and presented with advanced T-stage (73%) squamous cell carcinoma (93%) involving the alveolus (26%) retromolar trigone (21%) or oral tongue (25%). Median length of hospital stay was 8 days (range 4–22). The recipient site complication rate approached 34% and included infection (n=11), mandibular malunion (n=9), exposed bone or mandibular plates (n=11) and flap failure (n=5). Most patients demonstrated little to no trismus following reconstruction (81%) and were able to resume a regular or edentulous diet (61%). No difference in complication rates or postoperative outcomes was seen between osteocutaneous radial forearm and fibula free flap groups (P > 0.05). One patient underwent dental implantation following osteocutaneous radial forearm free flap reconstruction. No patients from the fibula free flap group underwent dental implantation.

Conclusion

The osteocutaneous radial forearm and fibula free flap provide equivalent wound healing and functional outcomes in patients undergoing lateral mandibular defect reconstruction.

INTRODUCTION

Oromandibular defect reconstruction following tumor resection remains a significant challenge for the head and neck surgeon. Unlike defects which involve the anterior mandibular arch, lateral defects result in disruption of the muscles of mastication and create an imbalance of the forces required to maintain mandibular form and function. A wide variety of reconstruction techniques have been described to restore continuity of the mandible including: nonvascular bone grafting,1 mandibular bridging with reconstruction plates2–4 and soft tissue or osteocutaneous free flap reconstruction. In a recent study by King et al.,5 patients who underwent vascularized bony reconstruction demonstrated improved functional results when compared to those who underwent soft tissue reconstruction alone.

Osteocutaneous free tissue transfer has therefore become the gold standard for mandibular defect reconstruction.6 Donor site selection however, has remained controversial. Donor sites most commonly include the fibula, scapula and iliac crest. Use of the osteocutaneous radial forearm free flap (OCRFFF) was first described in 1978,7 though early reports of donor site morbidity limited its widespread use until recently. Prophylactic radius plate fixation has reduced the risk of fracture and donor site morbidity.8 In a recent study comparing fibula and OCRFFF reconstruction of segmental mandibular defects,9 the OCRFFF was found to provide comparable functional outcomes with reduced overall morbidity. In the present study we evaluate outcomes in patients undergoing free flap reconstruction of lateral segmental mandibular defects and compare use of the fibula and OCRFFF in vascularized bony free flap reconstruction.

METHODS

Following Institutional Review Board approval, a retrospective review of all patients presenting to the University of Alabama at Birmingham and Oregon Health and Science University for lateral mandibular defect reconstruction between 1999 and 2010 was conducted. Lateral defects were defined as those which extended from the body of the mandible to the ipsilateral parasymphysis. A total of 137 patients were identified who underwent radial forearm swing (n = 8), radial forearm with bar (n = 5), osteocutaneous radial forearm (n = 73) or fibula free flap (FFF) reconstruction (n = 51).

Patients who required lateral mandibular defect reconstruction as a result of trauma or due to osteoradionecrosis were excluded from this study. Radial forearm swing reconstruction was performed when the overall condition of the mandible following tumor resection prevented more definitive repair or in accordance with patient preference. In all other cases a 2.4 mm locking reconstruction plate was utilized and adapted to the native mandible prior to tumor resection. No osteotomies were performed during fibula free flap reconstruction in order to allow for a side by side comparison of fibula and OCRFFF reconstruction techniques.

Patient demographics, tumor characteristics, adjuvant treatment, length of hospitalization, recipient and donor site complications and flap failure rates were reviewed. Early complications were defined as those occurring during the immediate postoperative period and required intervention. Late complications included those cases which required readmission. Extent of surgical resection including percent of oral tongue excised, pre- and postoperative dentition, dental implantation, trismus and postoperative diet were evaluated. Trismus was defined as the inability to achieve a mouth opening of 2 cm and considered severe if limited to 1 cm or less. Descriptive variables are reported as means (±SD) and categorical variables as percentages. Descriptive statistics were compared by general linear models for normally distributed variables or the Kruskal-Wallis test for otherwise. Survival time was calculated from date of surgery to date of death or date of last follow-up using the Kaplan-Meier method. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS® Ver. 9.2 software (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

From November 1999 to January 2010 a total of 137 patients underwent lateral mandibular defect free flap reconstruction. Mean age was 67.1 (range 31–96 years). The majority of patients were male (67%) and presented with advanced stage (73%) squamous cell carcinoma (93%) involving the alveolus (26%), retromolar trigone (21%) or oral tongue (25%) (Table I). One patient presented with two separate primaries involving the oral tongue and buccal mucosa and required a composite resection and partial glossectomy. Glossectomy (n = 37) was limited (<25% of tongue removed) in most patients who required resection (75%). Two patients underwent total glossectomy and 11 required near total resection.

TABLE I.

Patient Characteristics.

| Characteristic | OCRFFF (n = 73) |

Fibula (n = 51) |

P – value | All Patients (n = 137) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age – years | 0.94 | |||

| Mean (Range) | 66.6 | 66.4 | 67.1 (31 – 96) | |

| Gender (%) | 0.57 | |||

| Male | 48 (66) | 36 (70) | 92 (68) | |

| Female | 25 (34) | 15 (30) | 45 (32) | |

| Tumor subsite (%) | 0.01 | |||

| Alveolus | 16 (23) | 10 (20) | 35 (26) | |

| RMT | 11 (15) | 17 (33) | 29 (21) | |

| Oral Tongue | 11 (15) | 15 (29) | 35 (26) | |

| FOM | 13 (19) | 5 (10) | 19 (14) | |

| Buccal | 9 (13) | 1 (2) | 10 (7) | |

| Other | 11 (15) | 3 (6) | 10 (7) | |

| Histology (%) | 0.37 | |||

| SCC | 69 (96) | 46 (92) | 128 (93) | |

| Mucoepidermoid | 2 (3) | 3 (6) | 6 (4) | |

| Ameloblastoma | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 2 (2) | |

| Adenocarcionma | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | |

| T classification (%) | < 0.001 | |||

| T1 | 0 | 3 (6) | 3 (3) | |

| T2 | 11 (16) | 19 (39) | 31 (23) | |

| T3 | 11 (16) | 0 | 15 (11) | |

| T4 | 46 (66) | 27 (55) | 82 (62) | |

| Tx | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) | |

| Tongue resection (%) | 0.002 | |||

| None | 51 (70) | 27 (53) | 87 (64) | |

| < 25% | 12 (16) | 22 (43) | 37 (27) | |

| ≥ 25% | 10 (40) | 2 (4) | 11 (9) | |

| XRT (%) | 0.57 | |||

| Preoperative | 17 (25) | 15 (31) | 37 (28) | |

| Postoperative | 40 (59) | 24 (49) | 70 (54) | |

| None | 11 (16) | 10 (20) | 23 (18) | |

| Chemotherapy (%) | 0.42 | |||

| Yes | 9 (13) | 10 (20) | 20 (15) | |

| No | 60 (87) | 40 (80) | 112 (85) |

OCRFFF, osteocutaneous radial forearm free flap; RMT, retromolar trigone; FOM, floor of mouth; XRT, radiation

Thirty-seven patients (28%) had undergone previous radiation and 70 (54%) required postoperative radiotherapy; 20 (15%) required chemotherapy. There was no difference in adjuvant treatment between OCRFFF and fibula groups (P > 0.05). Mean follow up time was 17 months. Patients undergoing OCRFFF reconstruction demonstrated shorter follow-up times (12.5 months) when compared to those undergoing fibula free flap reconstruction (20.2 months; P = 0.02). This finding reflects the more recent use of the OCRFFF for lateral segmental defect reconstruction.

Reconstruction

The majority of patients (91%, n = 124) underwent osteocutaneous free flap reconstruction. The fibula was more commonly utilized in the reconstruction of retromolar trigone (n = 17, 33%) and oral tongue lesions (n = 15, 29%) while the OCRFFF was the preferred choice in buccal (n = 9, 13%) and lateral floor of mouth defect reconstruction (n = 13, 19%) (P = 0.01). Surprisingly, fibula free flap reconstruction was more commonly performed in patients requiring limited tongue resection (43% vs 16%) while patients with extensive defects were more likely to undergo OCRFFF reconstruction (40% vs 4%, P = 0.002). In accordance, more patients with advanced T-stage lesions (particularly T3) underwent reconstruction with the OCRFFF when compared to fibula reconstruction (P < 0.001). Mean mandibular defect size was similar between fibula (5.2 cm, range 4.63 to 5.80 cm) and OCRFFF groups (5.4 cm, range 3.72 to 7.02 cm) (P = 0.86).

Complications and Hospital Stay

The overall recipient site complication rate approached 28% (n = 39). Early complications including hematoma (n = 5), infection (n = 6) and fistula formation (n = 7) accounted for 46% of all complications. The majority of complications occurred following discharge (54%) and included bone or hardware exposure (n = 12) and mandibular malunion (n = 9). Flap failure occurred in 5 patients (4%). Two patients underwent repeat free flap reconstruction and 3 were left to swing following debridement and primary closure. Two patients developed venous congestion requiring anastamotic revision without further complications.

There was no difference in complication rates between OCRFFF and fibula groups (P > 0.05) (Table II). Early complications occurred in 15% of patients who underwent OCRFFF reconstruction compared to 8% of patients who underwent fibula free flap reconstruction (P = 0.07). Fistula formation occurred in 5 patients who were reconstructed with forearm flaps and 2 patients reconstructed with fibula flaps. Late complications occurred in 13% of OCRFFF reconstructed patients and 16% of fibula reconstructed patients (P = 0.94). Malunion occurred more frequently in patients undergoing fibula free flap reconstruction (n = 7 vs. n = 2 OCRFFF) while hardware or bone exposure typically occurred in patients who underwent OCRFFF reconstruction (n = 7 vs n = 1 FFF). Only one donor site complication occurred in a patient following fibula free flap reconstruction. The patient developed infection at the donor site incision, was readmitted, treated with IV antibiotics and discharged 3 days after the infection resolved. No OCRFFF donor site complications were reported.

TABLE II.

Complications Following Mandibular Defect Free Flap Reconstruction.

| Complications | OCRFFF (n = 73) |

Fibula (n = 51) |

P – value | All Patients (n = 137) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early | 0.07 | |||

| Hematoma | 3 | 0 | 5 | |

| Infection | 3 | 2 | 6 | |

| Fistula | 5 | 2 | 7 | |

| Late | 0.92 | |||

| Malunion | 2 | 7 | 9 | |

| Hardware or bone exposure | 7 | 1 | 12 | |

| Donor site | 0 | 1 | 1.00 | 1 |

| Flap failure | 3 | 2 | 0.94 | 5 |

Overall median length of hospital stay was 8 days (range 4 – 22 days). Patients who underwent fibula free flap reconstruction required longer hospital stays (10 days) when compared to patients who underwent OCRFFF reconstruction (8 days; P = 0.04).

Functional Outcomes

The majority of patients had a normal (58%) or modified diet (35%) with native dentition (55%) prior to reconstruction. Although a larger proportion of patients undergoing fibula free flap reconstruction presented with a modified diet when compared to those undergoing forearm reconstruction (57% vs. 22%; P < 0.001), there was no difference in postoperative diet between the two groups (P = 0.23) (Table III). Return of oral function was achieved in 89% of all patients at 12 months postoperatively. The majority of patients had little to no trismus at the time of last follow up (81%), maintained their native dentition (43%) and were able to tolerate a regular diet (32%); 7 (11%) remained gastrostomy tube dependent. Patients undergoing fibula free flap reconstruction were more likely to develop moderate to severe trismus (36%) when compared to patients undergoing OCRFFF reconstruction (12%, P = 0.008). Only one patient underwent dental implantation. The patient had undergone OCRFFF reconstruction and required bone grafting prior to implantation without complications.

TABLE III.

Preoperative and Postoperative Function and Dentition in Patients Undergoing Lateral Segmental Mandibulecotmy.

| OCRFFF (n = 73) |

Fibula (n = 51) |

P – value | All Patients (n = 137) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative Diet (%) | < 0.001 | |||

| Normal | 52 (75) | 17 (33) | 77 (58) | |

| Modified | 15 (22) | 29 (57) | 47 (35) | |

| G-tube | 2 (3) | 5 (10) | 9 (7) | |

| Diet at 12 mo (%) | 0.23 | |||

| Normal | 8 (35) | 10 (35) | 19 (32) | |

| Soft | 11 (48) | 9 (31) | 22 (37) | |

| Liquid | 1 (4) | 7 (24) | 12 (20) | |

| G-tube | 3 (13) | 3 (10) | 7 (11) | |

| Preoperative Dentition (%) | 0.77 | |||

| Native | 36 (54) | 29 (57) | 73 (55) | |

| Dentures | 7 (10) | 4 (8) | 11 (9) | |

| None | 24 (36) | 18 (35) | 47 (36) | |

| Postoperative Dentition (%) | 0.69 | |||

| Native | 28 (42) | 29 (45) | 58 (43) | |

| Dentures | 5 (7) | 4 (4) | 9 (7) | |

| None | 33 (49) | 18 (51) | 65 (49) | |

| Implants | 1 (2) | 0 | 1 (1) | |

| Trismus | 0.008 | |||

| None | 60 (88) | 29 (64) | 102 (81) | |

| Moderate | 6 (9) | 10 (22) | 16 (13) | |

| Severe | 2 (3) | 6 (14) | 8 (6) |

G-tube, gastrostomy tube.

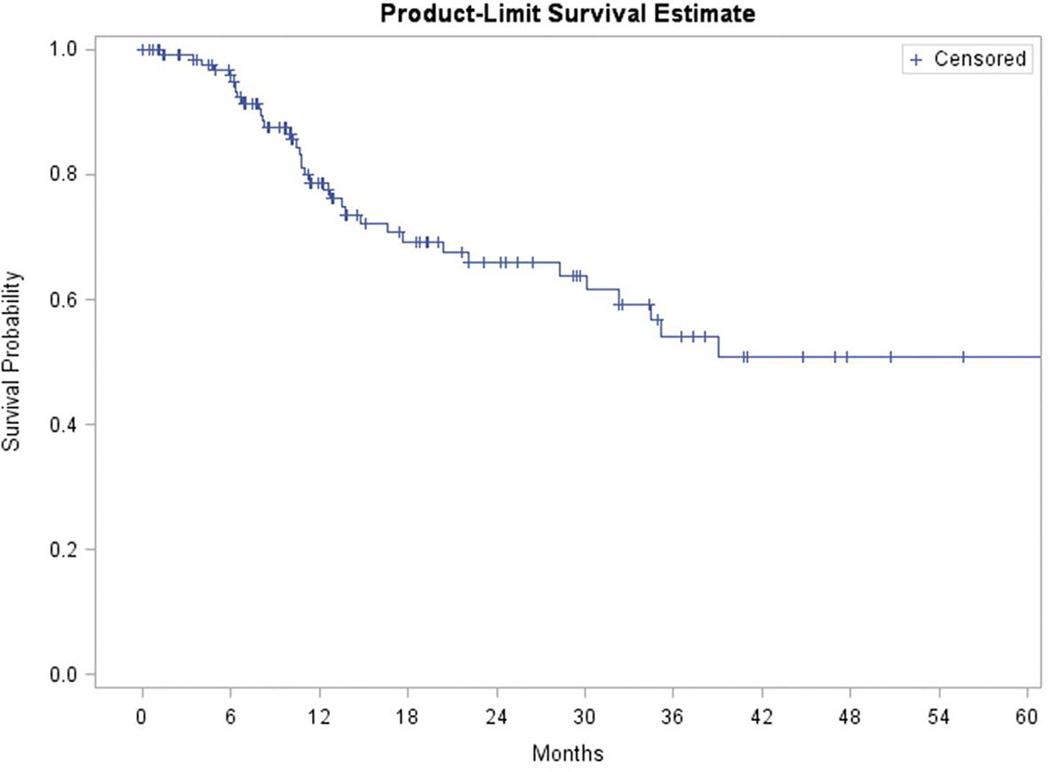

Survival

Overall 2-year disease free survival was 65.9% and 5-year disease free survival was 50.8% (Fig. 1). There was no difference in survival rates between OCRFFF and fibula groups (P = 0.23). Two-year disease free survival was 55.9% for OCRFFF reconstructed patients and 73.1% for fibula reconstructed patients.

Figure 1.

Overall survival for patients with lateral mandibular defects following free flap reconstruction.

DISCUSSION

Lateral segmental mandibular defect reconstruction following tumor resection remains a significant challenge for the head and neck surgeon. Since the development of microvascular free tissue transfer, osteocutaneous flaps have become the workhorse for maxillofacial and oromandibular soft tissue and bony reconstruction.10 The fibula free flap has long been considered the flap of choice for reconstruction of the mandible.11 Proponents of the flap site the length and quality of bone stock available and the ease at which dental implants can be placed. Several studies however, have shown future dental implantation is infrequent in this patient population9,12 and can be achieved with bone augmentation in OCRFFF reconstruction.9 The thin pliable nature of the radial forearm flap with its superior soft tissue characteristics and lack of bulk allows for reconstruction of a variety of head and neck defects and prophylactic plating of the radius has reduced donor site morbidity associated with its use. As a result, the OCRFFF has steadily gained popularity in mandibular reconstruction.9,12–14 In the present study we evaluated outcomes in patients undergoing free flap reconstruction of lateral segmental mandibular defects. Patients reconstructed with the OCRFFF required shorter hospital stays and demonstrated equivalent wound healing and functional results when compared to patients who underwent fibula free flap reconstruction.

No difference in functional outcomes including postoperative diet at 12 months was seen between patients undergoing osteocutaneous radial forearm and fibula free flap reconstruction (P = 0.23). Return of oral function was achieved in 89% of all patients and 32% were able to resume a regular diet; 7 patients (11%) remained gastrostomy tube dependent. In a study by Militsakh et al.,12 48% of OCRFFF patients maintained nutrition entirely by mouth at a mean time to follow up of 40 months. Similarly, no difference in postoperative diet was observed between OCRFFF and fibula and scapula free flap reconstruction groups.12 The majority of patients in this study were able to maintain their native dentition (43%) or had dentures placed following reconstruction (7%). Despite a reasonably long term survival rate (51% at 5 years) only one patient underwent dental implantation. The patient had undergone OCRFFF reconstruction and required bone grafting prior to placement of implants. In accordance with previous studies,8 the rate of dental implantation is low for this patient population and should not preclude use of the OCRFFF for mandibular reconstruction.

Just as dentition plays a critical role in the ability to tolerate a normal diet, trismus can severely limit a patient’s ability to take in oral nutrition. The majority of patients in this study demonstrated little to no trismus (81%); however patients undergoing fibula free flap reconstruction were more likely to develop moderate to severe trismus (36%) when compared to patients undergoing OCRFFF reconstruction (12%, P = 0.008). Whether the increased bulk of the fibula flap or other factors associated with tumor subsite and the resulting defect contributed to reduced mouth opening in these patients requires further clarification. Lateral mandibular defects can disrupt the muscles of mastication and create an imbalance of the forces required to maintain mandibular form and function. Perhaps the most likely explanation for this difference though is the larger number of malunion cases which occurred among patients following fibula free flap reconstruction.

Malunion is one of the most significant long term complications seen in mandibular reconstruction and typically results from poor vascularity of the bone stock or inadequate bone contact at the donor-recipient site.10 Although the OCRFFF bone stock is limited, evidence suggests that malunion is actually more common in fibula free flap reconstruction. While there was no significant difference in late complication rates observed between fibula and OCRFFF reconstructed patients (P = 0.92), malunion occurred more frequently among fibula free flap patients while bone or plate exposure tended to occur among those patients reconstructed with the OCRFFF. The later may be a function of reduced bone stock or the relative thinness of the OCRFFF in comparison to the skin paddle provided with the fibula flap. Early complications including infection, hematoma and fistula formation tended to occur more frequently in those patients who had undergone OCRFFF reconstruction (P = 0.07). While infectious complications are generally multifactorial in nature, one explanation could be due to the smaller soft tissue component provided by the OCRFFF in comparison to the fibula flap allowing for a potential dead space and risk of fluid accumulation. Importantly no flaps were lost as a result of infection. Microvascular free flap reconstruction was successful in 96% of cases and comparable to those reported at other institutions.9,12,15 Total flap failure rates were acceptable and equal among OCRFFF (4.1%) and fibula (3.9%) groups.

Early reports of significant donor site morbidity including fracture of the radius16,17 limited widespread use of the OCRFFF until recently. Prophylactic plate fixation of the donor radius and careful harvesting techniques which take no more than 40% of the radial width have drastically reduced the risk of fracture.8,10,13,18 In the present study no donor site complications occurred among the OCRFFF group. One patient who underwent fibula free flap reconstruction developed an infection at the donor site and required readmission and IV antibiotics without further complications. Despite comparable complication rates between both groups, patients who underwent fibula free flap reconstruction required longer hospital stays (9.7 days) when compared to patients who underwent OCRFFF reconstruction (8.4 days; P = 0.04). The majority of patients who require mandibular defect reconstruction following tumor resection are elderly (mean age for this patient population was 67 with a range of 31 to 96 years), and may experience prolonged difficulty with walking following fibula free flap reconstruction. Whether an extended hospital stay was a function of difficulty in ambulating during the postoperative period in these patients is left to be determined.

Previous studies have highlighted limitations to use of the OCRFFF in mandibular reconstruction.9 The flap is typically contraindicated when a bony defect of > 10 cm exists, if more than one osteotomy is required to achieve appropriate contour or in the presence of a large cutaneous or mucosal defect. In this study defects were limited to those spanning from the body to the ipsilateral parasymphysis and which required no osteotomies. Accordingly, mean mandibular defect size was similar between OCRFFF and fibula groups (P = 0.86). However, acceptable functional outcomes were achieved with use of the OCRFFF even in the presence of large T3/T4 lesions and those which encompassed the floor of mouth or required extensive tongue resection.

CONCLUSION

The OCRFFF is a viable option for select lateral segmental mandibular defect reconstruction and provides comparable functional outcomes to those seen following fibula free flap reconstruction. Complication rates were similar between OCRFFF and fibula free flap groups and hospital stay was reduced following radial forearm reconstruction. Although rare in this patient population, dental implantation can be achieved with bone grafting to augment the OCRFFF and should not preclude its use.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- 1.van Gemert JT, van Es RJ, Van Cann EM, et al. Nonvascularized bone grafts for segmental reconstruction of the mandible--a reappraisal. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:1446–1452. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2008.12.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blackwell KE, Buchbinder D, Urken ML. Lateral mandibular reconstruction using soft-tissue free flaps and plates. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1996;122:672–678. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1996.01890180078018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blackwell KE, Lacombe V. The bridging lateral mandibular reconstruction plate revisited. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;125:988–993. doi: 10.1001/archotol.125.9.988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arden RL, Rachel JD, Marks SC, et al. Volume-length impact of lateral jaw resections on complication rates. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;125:68–72. doi: 10.1001/archotol.125.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.King TW, Gallas MT, Robb GL, et al. Aesthetic and functional outcomes using osseous or soft-tissue free flaps. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2002;18:365–371. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-33017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bak M, Jacobson AS, Buchbinder D, et al. Contemporary reconstruction of the mandible. Oral Oncol. 46:71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2009.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Song R, Gao Y, Song Y, et al. The forearm flap. Clin Plast Surg. 1982;9:21–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Werle AH, Tsue TT, Toby EB, et al. Osteocutaneous radial forearm free flap: its use without significant donor site morbidity. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;123:711–717. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2000.110865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Virgin FW, Iseli TA, Iseli CE, et al. Functional outcomes of fibula and osteocutaneous forearm free flap reconstruction for segmental mandibular defects. Laryngoscope. 120:663–667. doi: 10.1002/lary.20791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim JH, Rosenthal EL, Ellis T, et al. Radial forearm osteocutaneous free flap in maxillofacial and oromandibular reconstructions. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:1697–1701. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000174952.98927.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cordeiro PG, Disa JJ, Hidalgo DA, et al. Reconstruction of the mandible with osseous free flaps: a 10-year experience with 150 consecutive patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104:1314–1320. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199910000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Militsakh ON, Werle A, Mohyuddin N, et al. Comparison of radial forearm with fibula and scapula osteocutaneous free flaps for oromandibular reconstruction. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;131:571–575. doi: 10.1001/archotol.131.7.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Militsakh ON, Wallace DI, Kriet JD, et al. The role of the osteocutaneous radial forearm free flap in the treatment of mandibular osteoradionecrosis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;133:80–83. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zenn MR, Hidalgo DA, Cordeiro PG, et al. Current role of the radial forearm free flap in mandibular reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;99:1012–1017. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199704000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Urken ML, Weinberg H, Vickery C, et al. Oromandibular reconstruction using microvascular composite free flaps. Report of 71 cases and a new classification scheme for bony, soft-tissue, and neurologic defects. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;117:733–744. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1991.01870190045010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith AA, Bowen CV, Rabczak T, et al. Donor site deficit of the osteocutaneous radial forearm flap. Ann Plast Surg. 1994;32:372–376. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199404000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thoma A, Khadaroo R, Grigenas O, et al. Oromandibular reconstruction with the radial-forearm osteocutaneous flap: experience with 60 consecutive cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104:368–378. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199908000-00007. discussion 79–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Villaret DB, Futran NA. The indications and outcomes in the use of osteocutaneous radial forearm free flap. Head Neck. 2003;25:475–481. doi: 10.1002/hed.10212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]