Abstract

Dental trauma occurs frequently in children and often can lead to pulpal necrosis. The occurrence of pulpal necrosis in the permanent but immature tooth represents a challenging clinical situation since the thin and often short roots increase the risk of subsequent fracture. Current approaches for treating the traumatized immature tooth with pulpal necrosis do not reliably achieve the desired clinical outcomes, consisting of healing of apical periodontitis, promotion of continued root development and restoration of the functional competence of pulpal tissue. An optimal approach for treating the immature permanent tooth with a necrotic pulp would be to regenerate functional pulpal tissue. This review summarizes the current literature supporting a biological rationale for considering regenerative endodontic treatment procedures in treating the immature permanent tooth with pulp necrosis.

Keywords: regenerative endodontics, pulpal revascularization, stem cells, trauma, children

Introduction

This Symposium includes a number of papers focused on diagnosis, prognosis and treatment of the traumatized tooth. Here we provide a biological rationale for considering regenerative endodontic treatment procedures. A companion paper in this Symposium discusses considerations for the clinical protocol of a regenerative endodontic procedure (1).

Dental trauma occurs frequently in children and often can lead to pulpal necrosis. Population-based studies from around the world indicate that the prevalence of dental trauma injuries is about 4–59%, with the majority of cases occurring in incisors (2). The broad range in estimated prevalence rates may be due in part to differences in sampling methods or study populations. In one study of 262 Swiss children aged 6–18, the prevalence of dental trauma was nearly 11% and about 12% of enamel-dentin fractures led to pulpal necrosis (3). In another study of 889 permanent teeth with traumatic injuries, pulpal necrosis occurred in about 27% of the sampled population (4). The risk of developing pulpal necrosis is well recognized to be dependent upon the type of dental trauma. In an analysis of 10,673 permanent teeth seen at a tertiary care center, pulpal necrosis was estimated to range from 0% (infraction), to 3% (concussion), to 26% (extrusion), to 58% (lateral luxation), to 92% (avulsion), to 94% (intrusion), (5).

The occurrence of pulpal necrosis in the permanent but immature tooth often represents a challenging clinical situation since the thin and often short roots increase the risk of subsequent fracture; indeed overall survival of the replanted permanent teeth has been reported to range from 39–89% (6). In treating the immature tooth with pulpal necrosis, the ideal clinical outcomes would be to prevent or heal the occurrence of apical periodontitis, promote continued root development and restore the functional competence of pulpal tissue, particularly from both immunological and sensory perspectives (7). These outcomes would very likely increase the long term probability of retaining the natural dentition. Unfortunately, alternative procedures (eg., implants) are often contraindicated due to the still growing craniofacial skeleton in these young patients.

Treating the Immature Necrotic Tooth by Revascularization or Apexification

Current approaches (eg., replantation) for treating the traumatized immature tooth with pulpal necrosis do not reliably achieve healing of apical periodontitis, continued root development and reestablishment of pulpal immunological and sensorial competency. In one study, only 34% (32 of 94) of replanted immature permanent teeth exhibited pulpal healing (6). Another study reported an 8% revascularization rate (13 of 154) in replanted teeth, with this outcome defined as continued root development and an absence of radiographic signs of apical periodontitis or root resorption (8). These values are similar to a reported range of pulpal healing of about 4–15% in a series of 470 replanted teeth reported by various authors (6). Importantly, the diameter of the apical opening (≥1mm), extraoral time (<45 min) and the arch (mandibular) were all significant predictors for improved revascularization of replanted avulsed teeth (8). Thus, the classic “revascularization” procedure of simply replanting an avulsed permanent tooth does not reliably achieve the goals of preventing apical periodontitis, triggering continued root development and restoring functional competence of the pulp tissue.

An alternative approach for treating the immature permanent tooth is apexification procedures. The classic apexification method involves long term application of Ca(OH)2, which may weaken teeth (9, 10) and is associated with increased risk of cervical fractures (11, 12). A more recent method of apexification involves the use of MTA as an apical barrier followed by placing either a root filling or obturating material (13). MTA apexification appears to offer superior advantages over the traditional Ca(OH)2 method (14), reducing the number of treatment appointments, increasing patient compliance, improving rate of healing (15) and reducing the risk of subsequent fracture (12), although other outcomes such as apical barrier formation may be similar between the two methods (16). However, it is important to note that apexification by either Ca(OH)2 or MTA completely prevents any further root development in terms of increased radiographic measures of either root length or width (12, 17). Thus, the immature tooth treated by apexification procedures demonstrates healing of apical periodontitis, but does not achieve the goals of continued root development or restoration of functional pulp tissue.

Regeneration of Functional Pulpal Tissue

An optimal approach for treating the immature permanent tooth with a necrotic pulp would be to regenerate functional pulpal tissue. Regenerative endodontics has been defined as “biologically based procedures designed to replace damaged structures, including dentin and root structures, as well as cells of the pulp-dentin complex” (18). As recently observed, the goal of tissue regeneration (e.g., formation of new tissue reproducing both the anatomy and function of the original tissue) is distinct from tissue repair (e.g., development of a replacement tissue, such as scar tissue, without restoration of function) (19, 20). The concept of regenerating pulpal tissue was promulgated by the classic studies of Nygaard-Ostby who evaluated the effects of evoked bleeding by over-instrumentation of human or dog root canal systems. Unfortunately, histological analysis revealed tissue repair (e.g., fibroblasts, collagen, sparse vascularity) without histological evidence of regeneration of the pulp-dentin complex (21–23). Together with findings from the trauma literature regarding the negative impact of infection on revasacularization, the studies of Nygaard-Ostby and others (24–26) contributed to a fundamental shift in the focus of endodontic research from the 1970s onward, away from a biological regenerative objective and towards a restorative dental philosophy for endodontic treatment, including disinfection and placement of root fillings.

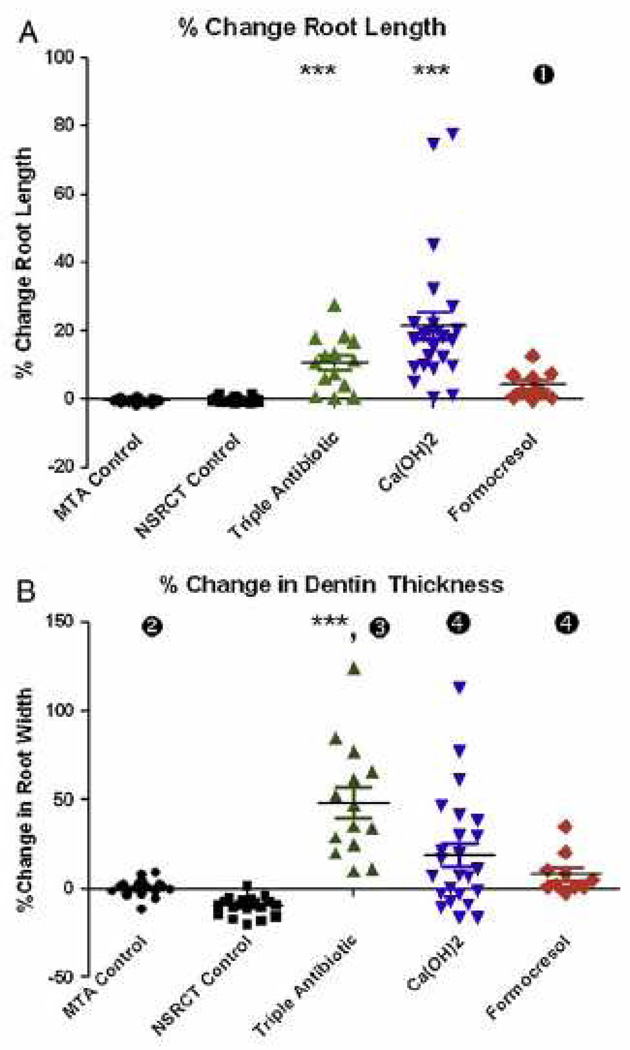

Over the period of 1993–2007, several key publications prompted a re-emergence of a biological, or regenerative approach for endodontic treatment. During this period, several case reports were published where immature permanent teeth with pulp necrosis were disinfected followed by laceration of the apical tissue and placing a coronal restoration. The resulting clinical outcome was a resolution of sinus tracts, pain, swelling and a dramatic increase in radiographic root length and width, which often occurred 0.5–2 years after treatment (27–31). Since these original case reports, numerous studies have been published reporting varying clinical outcomes following regenerative procedures (12, 30, 32–50). Successful outcomes have been reported after treating immature permanent teeth with pulpal necrosis due to trauma, development defects, or caries. A retrospective analysis by Bose et al., (Fig 1) on 48 regenerative cases reported a significant increase in radiographic root development for both root length and root width as compared to MTA apexification procedures (17). These findings were recently replicated in an independent patient population (12), which extended the original findings of Bose and colleagues by demonstrating significantly greater tooth survival after regenerative treatment (100%) compared to teeth treated with Ca(OH)2 apexification (77%). Although caution must be applied to these clinical findings since case reports may be biased for reporting positive outcomes (51), the preponderance of publications to date suggest that regenerative endodontic treatment of the immature permanent tooth can lead to healing of apical periodontitis, continued radiographic root development and improved tooth survival.

Fig 1.

(A) Percentage change in root length from preoperative image to postoperative image, measured from the CEJ to the root apex. ***P < .001 versus MTA apexification control group (n = 20) and NSRCT control group (n = 20). (1) P < .05 versus MTA control group only. Median values for each group are depicted by horizontal line, and individual cases are indicated by the corresponding symbol. (B) Percentage change in dentinal wall thickness from preoperative image to postoperative image, measured at the apical third of the root (position of apical third defined in the preoperative image). ***P < .001 versus MTA apexification control group and NSRCT control group. (2) P < .05 versus NSRCT control group only. (3) P < .05 versus Ca(OH)2 and formocresol groups. (4) P < .05 versus NSRCT control group only. Reprinted from Bose et al., J Endod 35:1343, 2009 with permission.

There is clearly a need for randomized controlled studies comparing various procedures for treating the immature tooth with pulpal necrosis. However, given that these studies have not yet been completed, clinicians are forced to use a lower level of clinical evidence, based upon available reports. Alternatively, some investigators have suggested that the lack of randomized controlled studies or long term follow-up should restrict the use of regenerative procedures to only those cases when all other treatments are either not suitable or have failed (44). However, this is not a practical solution. Practicing endodontists must treat patients based upon the best available evidence, which in many situations is not a randomized clinical trial with years of follow-up. As examples of this general issue, both traditional surgical and non-surgical endodontic treatments provide strong benefit in treating apical periodontitis, even though comparatively few randomized controlled trials have been conducted (52, 53). Although we agree with the need for continued clinical studies on regenerative endodontics, the available level of evidence is sufficient to provide patients with this treatment option. Finally, as active clinicians who must make real-life decisions in treating our patients, we respectfully observe that many clinical decision points will never be evaluated by randomized controlled trials (eg., randomizing patients to i.v. bisphosphonates or placebo prior to apical surgery; or randomizing patients to a retained instrument within a root canal system prior to completion of non-surgical endodontic treatment) – and yet, clinicians are still expected to use their best judgment of available evidence in caring for their patients (54, 55). Indeed, the entire concept of “level of evidence” is to use the best available evidence, and not to withhold treatment simply because the level of evidence is not ideal.

Biological Basis for Regeneration

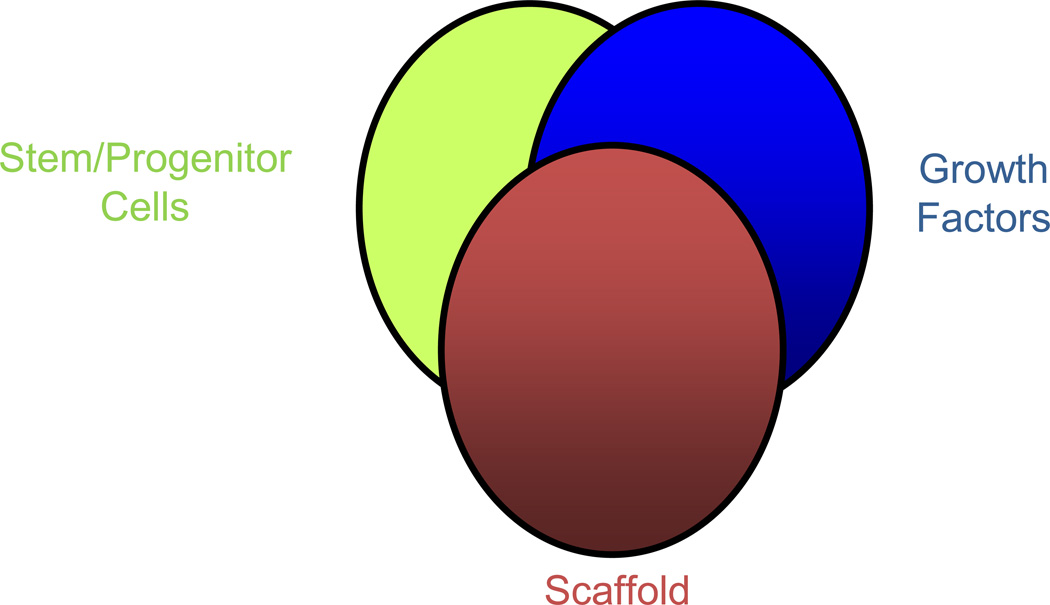

A second major contribution over the period of 1993–2007, was the development of the field of tissue engineering (56). Simply put, tissue engineering integrates the fields of biology and engineering into a discipline that is focused on tissue regeneration, instead of tissue repair. Fig 2 illustrates the core principles of tissue engineering, namely that tissue regeneration requires an appropriate source of stem/progenitor cells, growth factors and scaffolds in order to control the development of the targeted tissue.

Fig 2.

Three main components of tissue engineering

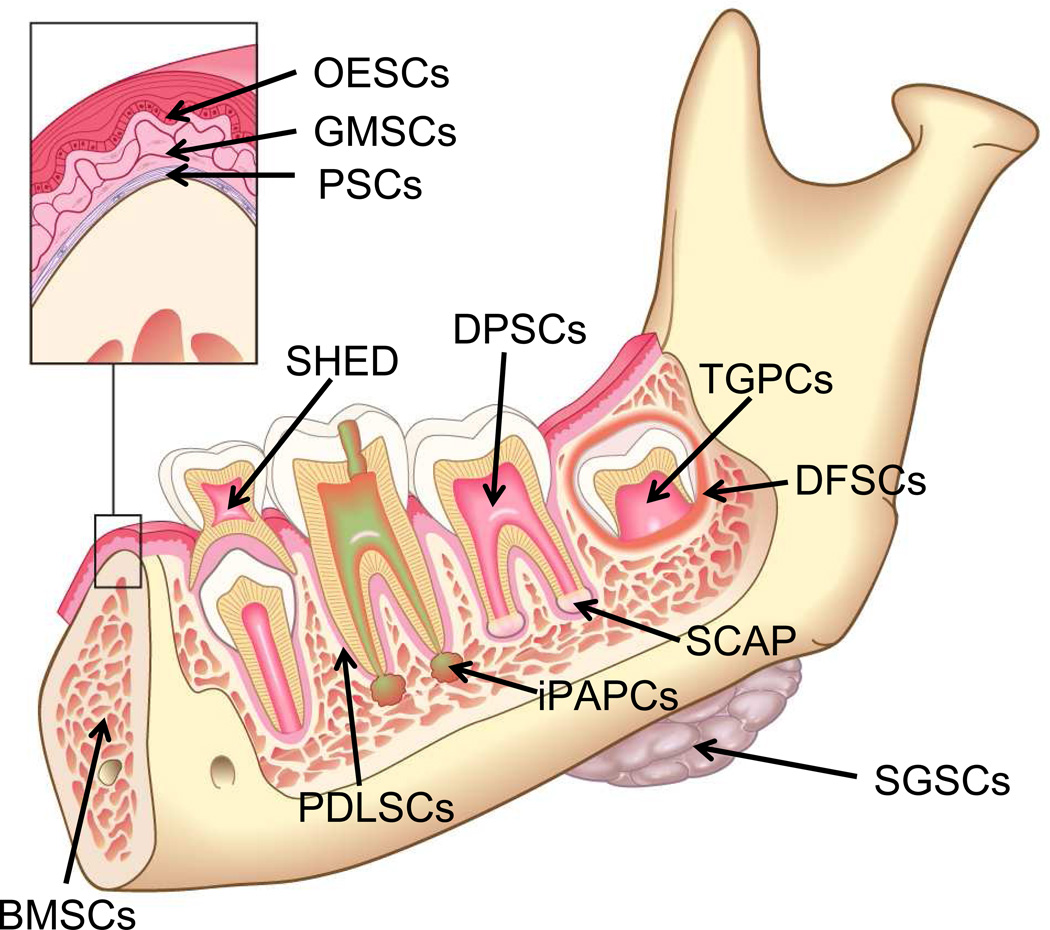

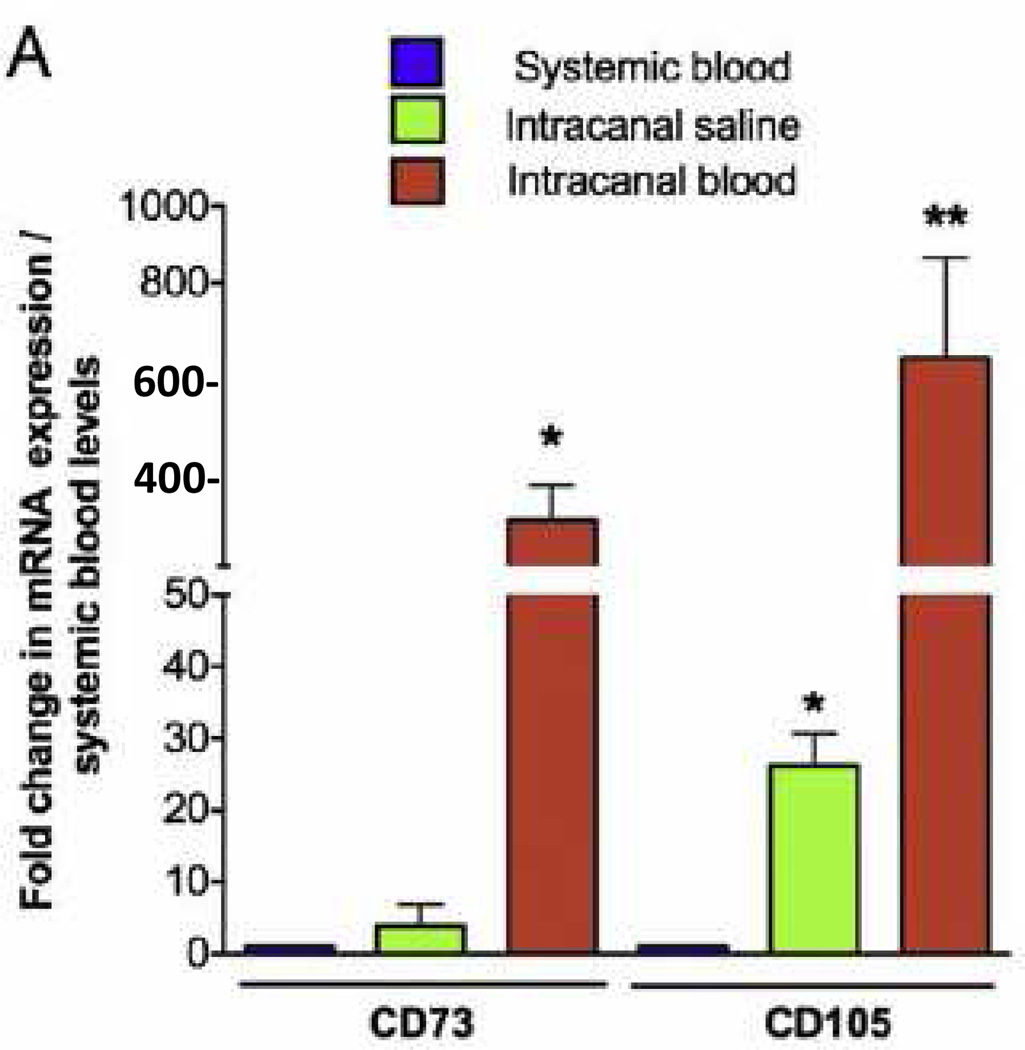

The first element of tissue engineering is a source of cells capable of differentiating into the desired tissue component. Fig 3 is based upon an elegant review by Egusa and colleagues (57) and summarizes several stem cell types available in the oral and craniofacial region. Detailed reviews are available that summarize the properties of these orofacial stem cells (57–62). Interestingly, stem cells are found in dental pulp (63, 64), the apical papilla (59, 60) and even the inflamed periapical tissue collected during endodontic surgical procedures (65). These findings suggest an opportunity for harvesting stem cells during clinical procedures. Indeed, the evoked bleeding during endodontic regenerative procedures conducted on immature teeth with pulpal necrosis reveals a massive influx of mesenchymal stem cells into the root canal space (66). As shown in Fig 4, laceration of the apical papilla in patients triggers an inflow of blood into the root canal space that has a 400- to 600-fold greater concentration of mesenchymal stem cell markers (CD73 and CD105) as compared to concentrations of these cells circulating in the patient’s systemic blood. Thus, several local sources of stem cells are available for clinical dental procedures and stem cells can be delivered into the root canal system of patients.

Fig 3.

Schematic drawing illustrating potential sources of post-natal stem cells in the oral environment. Cell types include tooth germ progenitor cells (TGPCs), dental follicle stem cells (DFSCs), salivary gland stem cells (SGSCs), stem cells of the apical papilla (SCAP), dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs), stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth (SHED), periodontal ligament stem cells (PDLSCs), bone marrow stem cells (BMSCs) and, as illustrated in the insert, oral epithelial stem cells (OESCs), and gingival-derived mesenchymal stem cells (GMSCs)

Fig 4.

Evoked-bleeding step in endodontic regenerative procedures in immature teeth with open apices leads to significant increase in expression of undifferentiated mesenchymal stem cell markers in the root canal space. Systemic blood, saline irrigation, and intracanal blood samples were collected during second visit of regenerative procedures. Real-time RT-PCR was performed by using RNA isolated from each sample as template, with validated specific primers for target genes and 18S ribosomal RNA endogenous control. (A) Expression of mesenchymal stem cell markers CD73 and CD105 was up-regulated after the evoked-bleeding step in regenerative procedures. Reprinted from Lovelace, et al., J Endod 37:133, 2011 with permission.

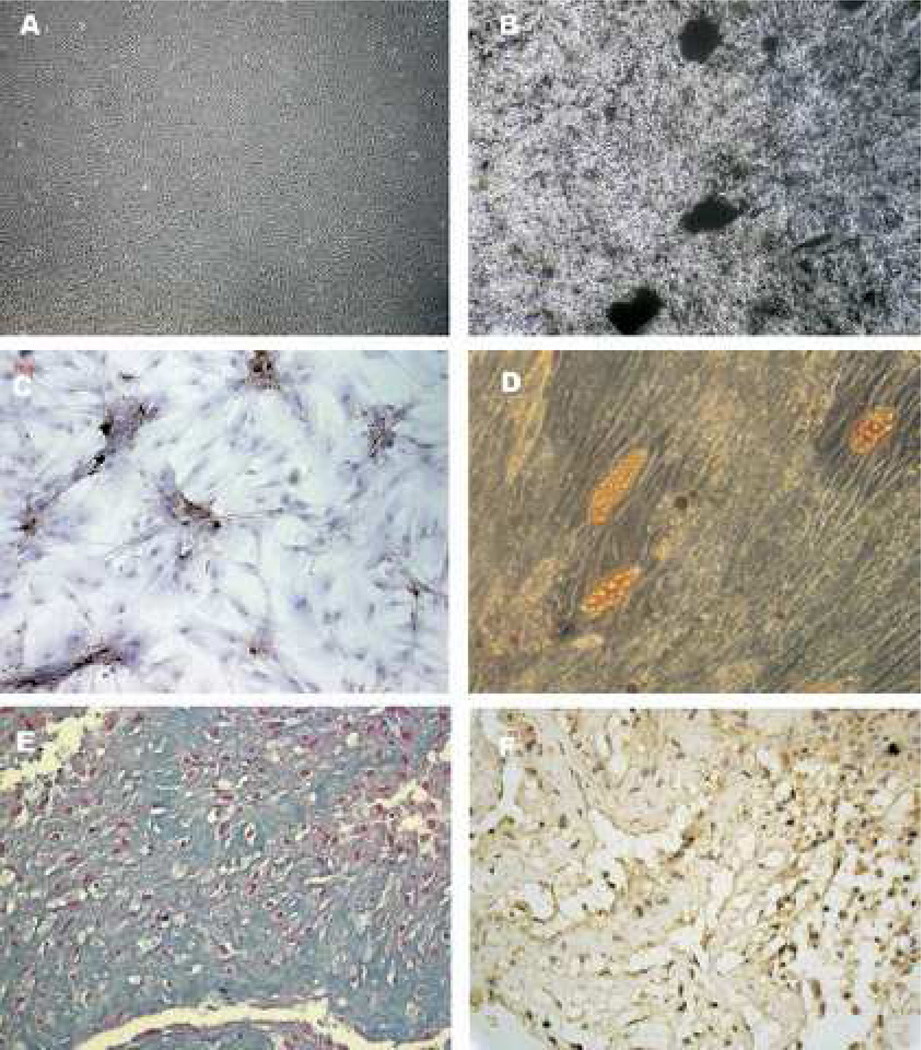

The second element of tissue engineering focuses on growth factors or other tissue-inducing mediators. Stem cells have the capacity to differentiate into a number of cell phenotypes depending on their lineage and exposure to environmental stimuli such as growth factors, extracellular matrix, hypoxia or other conditions (65, 67–73). Thus, the environment is a critical factor in regulating tissue differentiation. For example, Fig 5 is taken from the study of Wei and colleagues and demonstrates that exposure of the same population of dental pulp cells to three different combinations of growth factors results in cells that express a mineralizing phenotype (Fig 5B, C), an adipocyte (fat cell) phenotype (Fig 5D) or a cartilage-like phenotype (Fig 5E, F). These general findings have been repeated in numerous studies on orofacial stem cells and represent a distinctive property of stemness. Thus, the mere step of lacerating the apical papilla and delivering a high local concentration of stem cells into the root canal space may not be sufficient to guide their differentiation into cells of the pulp-dentin complex. Instead, growth factors should be considered as important adjuncts. This is an important concept to remember when interpreting histological studies after regenerative procedures.

Fig 5.

Multilineage differentiation capacity of DPCs. DPCs cultured in alpha-MEM with 15% FBS (control medium) was shown in A (original magnification X 40). Odontogenic differentiation was shown by the deposition of a mineralized matrix indicated by von Kossa stain shown in B (original magnification X 100) and by the positive immunostaining of DSP shown in C (original magnification X 200). Adipogenic differentiation was shown by the accumulation of neutral lipid vacuoles stainable with Oil Red O shown in D (original magnification X100). Chondrogenic differentiation was shown by the secretion of cartilage-specific proteoglycans stainable with Alcian blue shown in E (original magnification X400) and by the positive immunostaining of collagen type II shown in F (original magnification X400). These results were representative of three to four independent experiments. Reprinted from Wei, et al., J Endod 33:703, 2007 with permission.

The third element of tissue engineering is a scaffold. A scaffold is much more important than simply forming a three dimensional tissue structure. In addition, scaffolds play a key role in regulating stem cell differentiation by local release of growth factors or by the signaling cascade triggered when stem cells bind to the extracellular matrix and to each other in a 3-dimensional environment (72, 74–76). Scaffolds may be endogenous (eg., collagen, dentin, etc) or synthetic substances (e.g., hydrogels, MTA or other compounds) (77, 78). This principle may play a very important role in interpreting clinical regenerative studies. For example, instrumentation of dentin cylinders followed by irrigation with 5.25% NaOCl and extensive washing led to a dentin surface that promoted differentiation of cells into clastic-like cells capable of resorbing dentin (71). In contrast, irrigation of dentin cylinders with 17% EDTA either alone, or after NaOCl treatment, produced an dentin surface that promoted cell differentiation into cells expressing an appropriate marker for a mineralizing phenotype (eg., dentin sialoprotein) (71). Accordingly, the selection of irrigants and their sequence (EDTA last) may play critical roles in conditioning dentin into a surface capable of supporting differentiation of a desired cell phenotype.

Some controversy exists over the terms “regeneration” versus “revascularization” (79, 80). The term revascularization emerged from the trauma literature, and the observation that pulp in teeth with transient or permanent ischemia, in certain cases, could have reestablishment of its blood supply. These studies laid the foundational knowledge of factors important for revascularization to occur, notably the evidence that teeth with immature roots and open apices had increased rates of revascularization and continued root development. Although these important findings have a significant influence in contemporary regenerative endodontic procedures, they do not include the intentional use of bioengineering principles in achieving repair and regeneration of a missing dental pulp. Instead, contemporary regenerative endodontic procedures consider the presence of an enriched source of stem cells within the apical papilla, their delivery into root canal systems and the intentional release and use of local growth factors embedded into the dentin. Thus, contemporary regenerative endodontics departs from its origins based on the trauma literature and embarks in the field of bioengineering.

From our perspective, regeneration indicates an overall goal of reproducing the original tissue histology and function. To date, the approach that appears to offer the greatest opportunity for regeneration is tissue engineering. Since high concentrations of stem cells are delivered into the root canal space when lacerating the apical papilla in the immature permanent tooth (66), this clinical procedure accomplishes one key component of the triad of tissue engineering (Fig 2). Ongoing research, much of it preclinical, has evaluated combinations of stem cells, growth factors and scaffolds that lead to histological regeneration of pulp tissues that fulfill many of the criteria for a pulp-dentin complex (81–86). In contrast, the concept of revascularization focuses only on the delivery of blood into the root canal space as a means of prompting wound healing, similar to healing after extraction of a tooth (21). In addition, revascularization is a term better employed for the reestablishment of the vascularity of an ischemic tissue, such as the dental pulp of an avulsed tooth. From this perspective, a focus on “revascularization” would ignore the potential importance of growth factors and scaffolds that are required for histological recapitulation of the pulp-dentin complex. Although we appreciate that angiogenesis and the establishment of a functional blood supply is a key feature in the maintenance and maturation of a regenerating tissue, it is noteworthy that some of the published cases report positive responses to pulp sensitivity tests such as cold or EPT. This is evidence that a space that was previously vacant (debrided root canal) may become populated with an innervated tissue supported by vascularity. Taken together, the core concepts of tissue engineering (Fig 2) distinguish a regenerative treatment philosophy from a revascularization philosophy derived from certain trauma cases (which only occur in a low percentage of replanted teeth).

Overview of Current Literature from a Tissue Engineering Perspective

From the perspective of the triad of tissue engineering, current clinical regenerative protocols may not achieve histological regeneration. Current clinical protocols partially meet the triad criteria, since stem cells are delivered into the root canal space (66), dentin and the fibrin clot may serve as scaffolds (42, 69, 71, 87) and certain growth factors are both embedded in dentin (88, 89) and released from platelets during the clotting cascade (90, 91). However, the composition of cells, growth factors and scaffolds is not controlled and likely to vary with differences in clinical protocol or tooth condition. In addition, an emerging body of evidence indicates that both irrigants (71, 92) and medicaments such as the triple antibiotic paste (93), may adversely affect stem cell differentiation or survival. Thus, current clinical protocols are largely tailored towards the disinfection of root canal systems, but fail to incorporate many of the required procedures needed for more complete and organized regeneration of the pulp-dentin complex.

These issues are perhaps best exemplified by preclinical and clinical histology of tissues found in the root canal space after the current clinical protocols. In general, the use of current protocols results in the production of many histological elements of pulp tissue (eg., fibroblasts, blood vessels, collagen), but other cell types are missing (e.g., odontoblasts) and non-targeted cell types or tissues may be present (eg., osteoblasts, cementum) (42, 94–100). In contrast, preclinical studies that deliver specific growth factors, scaffolds and stem cells into the root canal space have demonstrated the histological regeneration of pulp tissues that fulfill nearly all the criteria for a pulp-dentin complex, including production of cells with an odontoblast-like phenotype (81–86). Thus, continued translational research is needed to evaluate the effects of delivery of specific growth factors and scaffolds to determine if these elements impact histological regeneration of the pulp-dentin complex in patients.

The second outcome from a regeneration perspective is a functional or clinical success. The available clinical reports are consistent with the notion that current clinical regenerative protocols achieve many aspects of successful clinical outcomes. For example, the vast majority of published cases report closure of sinus tracts (if present), resolution of pain, healing of apical periodontitis, increased radiographic development of root length and width, and overall tooth survival (12, 27–50). Although this clinical evidence is at the level of case reports/case series, they are based on actual outcomes reported by clinicians in treating real-life patients. Thus, there is good evidence for functional outcomes that are clinically meaningful.

Understanding the distinction between clinically meaningful functional outcomes and histological outcomes is important. This general issue applies to all aspects of clinical endodontics. For example, several histological studies have been conducted with human material after non-surgical endodontic treatment (NSCRT). In general, studies have reported the presence of histologic signs of periapical inflammation even in teeth with radiographically normal periapical tissues. Although the presence of inflammatory tissue has been reported in about 94% of cases using a historical treatment method (101), more contemporary studies report histologic signs of periapical inflammation in 26–32% of cases without radiographic signs of apical periodontitis (102, 103). These histologic studies are consistent with a dichotomy between clinical measures of success and actual tissue histology. Since treatment success is primarily based on clinical, and not histological, outcomes for evaluating contemporary NSRCT treatments, it seems reasonable that the more important factors in evaluating treatment success in regenerative endodontics are functional measures of clinical outcome.

From this perspective, we have conducted a retrospective analysis of published cases on regenerative treatment of immature teeth with pulpal necrosis. A PubMed search was conducted in September 2012 using the search terms (revascularization or regeneration) AND (endodontic or “root canal”). The resulting 1,044 hits were then analyzed by title and abstract and the results of the 29 accepted studies describing regenerative treatment are summarized in Table 1. The etiology of the pulpal and periradicular disease of these published cases are comprised of dens evaginatus (39.7%), trauma (35.5%), caries (14%), dens invaginatus (1.6%) or undisclosed-unknown factors (9.2%). Thus, about 1/3 of the published studies on regenerative endodontic treatment involve treatment of trauma. A common feature of the published case reports is the rapid resolution of apical periodontitis, and other signs and symptoms of pathosis such as sinus tracts and swelling (104–109). In addition, clinically evident root development and/or apical closure was reported in most cases. Thus, regenerative endodontic protocols have been used successfully in clinical cases of varied etiology, including a significant number trauma cases.

Table 1.

Current published case reports or case series of revascularization/ regenerative procedures in endodontics. Sample size listed on the table denote only to the number of teeth treated with revascularization/regeneration protocols. N/A= information not available.

| Authors | Reference # | Sample Size | Etiology | Diagnosis | Clinical Outcomes | Post-treatment Vitality (Sensitivity) Responses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nygaard-Ostby, 1961 | 21 | n=17 | N/A | Vital pulp (n=?) Necrotic Pulp with Apical Periodontitis (n=?) | Histologic outcome: Healing of the periodontal tissue damaged by over instrumentation occurred very quickly in as little as 35 day. In addition, all cases demonstrated in-growth of connective tissue into the canal space with fiber bundles running parallel to the canal wall, or inserting into the newly formed intracanal mineralized tissue (identified as cementum). The tissue resember fibrous connective tissue with numerous capillaries and "undifferentiated mesenchymal elements" near the capillaries. | N/A |

| Rule and Winter, 1966 | 26 | n=5 | Trauma (n=3); Dens invaginatus (n=1); not disclosed (n=1) | Necrotic pulp (n=5) with Aacute Apical Abscess (n=2); Chronic Apical Abscess (n=2) or Symptomatic Apical Periodontitis (n=1) | Resolution of signs and sympotoms of pathosis, including perapical radiolucencies. In addition, all cases demonstrated demonstrated continued root development and/or apical closure (6 months to 1 year) | N/A |

| Nygaard-0 and Hjortdal, 1971 | 22 | n=47 | N/A | Vital pulp (n=35) ;Necrotic pulp (n=12) | Histological outcome: there was evidence of a vascularized fibrous connective with often deposition of cellular cementum along the root canal walls in teeth previously diagnosed as having a vital pulp, whereas no repair was seen in teeth previously diagnosed with a necrotic pulp (9 days to 3 years follow-up). | N/A |

| Iwaya et al., 2001 | 27 | n=1 | Dens evaginatus (tooth #29) | Necrotic pulp and Chronic Apical Abscess | Complete resolution of signs and symptoms of pathosis. Initial apical closure observed at the 5-months recall visit with complete closure and evidence of root development at 30-months recall visit | Yes |

| Banchs and Trope, 2004 | 28 | n=1 | Dens evaginatus (Tooth #29) | Necrotic pulp and chronic apical abscess | Periradicular lesion healed (6 months recall); continued root development (12-month recall); Root development, apical closure and cold response (2 year follow-up) | Yes |

| Thibodeau and Trope., 2007 | 93 | n=1 | Trauma (complicated crown fracture; tooth #9) | Necrotic pulp and acute apical abscess | Pt was asymptomatic with evidence of continued root development and apical closure and partial canal obliteration (12.5 months follow-up) | No |

| Shah et al., 2008 | 38 | n=14 | Trauma [n=10 (complicated coronal fractures, n=9 and lateral luxation, n=1)]; not disclosed (n=4) | Pulp Necrosis (n=14) with Apical Chronic Apical Abscess (n=4) or Acute Apical Abscess (n=5) or Apical Periodontitis (n=6) | Periapical resolution of radiolucencies (93% or 13/14). Root development (21.4% or 3/14) with evident thickeing if lateral dentinal walls (57% or 8/14) and resolution of clinical sings and symptoms (78% or 11/14). | N/A |

| Cotti et al., 2008 | 33 | n=1 | Trauma (complicated crown fracture) | Pulp Necrosis with Chronic Apical Abscess | Resolution of signs and symtoms of pathosis, including sinus tract and associated radiolucency; continued root development (3–30 months follow-up). | No |

| Jung et al., 2008 | 45 | n=8 | Dens Evaginatus (tooth #29; n=2); Not disclosed (n=5); Caries (n=1) | Necrotic Pulp (n=5) or Previously Initated Therapy (n=3) with Chronic Apical Abscess (n=4), Acute Apical Abscess (n=1), Symptomatic Apical Periodontitis (n=2) or Asymptomatic Apical Periodontitis (n=1) | All patients became asymptomtic and demonstrated healing of apical periodontitis (100% or 8/8 at 1 to 3 months recall). In addition, root development was evident in 75% of the cases (6/8 at 10 months –5 years recall). | N/A |

| Reynolds et al., 2009 | 46 | n=2 | Dens evaginatus (tooth #20 and #29) | Necrotic pulp and Chronic Apical Abscess | Both teeth remained asymptomatic, with demonstration of periradicular healing and continued root development with apical closure. Both teeth responded to EPT. In adidition, tooth #29 did not demonstrated discoloration often seen with TAP treatment due the sealing of dentinal tubules with a bonding material. | Yes |

| Chueh et al., 2009 | 32 | n=23 | Dens evaginatus (n=22); Trauma (n=1, complicated crown fracture) and Caries (n=1) | Pulp necrosis (n=18), Previously Initiated Therapy (n=5) with Acute Apical Abscess (n=8), Chronic Apical abscess (n=8), Symptomatic Aapical periodontitis (n=3) or Asymptomatic Apical Periodontitis (n=4). | There was evidence of resolution of apical periodontitis with resolution of radiolucencies and continued root development (100% of cases; n=23; 3–29 months follow-up) | N/A |

| Shin et al., 2009 | 40 | n=1 | Caries (tooth #29) | Pulp Necrosis and Chronic Apical Abscess | There was evidence of periradicular lesion healing (7 months recall). Also, there was thickening of the dentinal walls and continued root development (13–19 months follow-up). | No |

| Ding et al., 2009 | 47 | n=3 | Dens invaginatus (tooth #29); Caries (Tooth #29); Trauma (complicated crown fracture; tooth #9) | Pulp Necrosis (n=3) with acute apical abscess (n=2) and undisclosed periradicular status (n=1) | There was evidence of thickening of the dentinal walls, closure of apex (15–18 months follow-up). | Yes |

| Thomson and Kahler., 2010 | 41 | n=1 | Dens evaginatus (tooth #20) | Pulp Necrosis with Chronic Apical Abscess | There was resolution of signs and symptoms of pathosis, including closure of sinus tract; evidence of root development and positive response to EPT testing (18 months follow-up) | Yes |

| Petrino et al., 2010 | 37 | n=6 | Trauma (complicated crown fracture n=2, avulsion n=2); Caries (n=2) | Pulp Necrosis (n=6), with Asymptomatic Apical Periodontitis (n=4) or Chronic Apical Abscess (n=2). | There was evidence of periradicular healing with resolution of signs and symptoms of pathosis (100% of cases; n=6). In addition, continued root development was seen in 3 cases (50% of cases), whereas response to pulpal sensitivity testing was seen in 2 cases (33.3% of cases). | Yes |

| Kim et al., 2010 | 108 | n=1 | Trauma (uncomplicated crown fracture) | Pulp Necrosis and Symptomatic Apical Periodontitis | Tooth was asymptomatic with resolution of periradicular radiolucency. There was evindece of continued root development with apical closure (8 months recall) | N/A |

| Nosrat et al., 2011 | 36 | n=2 | Trauma (n=2) (complicated crown fracture tooth #8, and uncomplicated coronal fracture tooth #9) | Pulp Necrosis and Symptomatic Apical Periodontitis | Tooth was asymptomatic and apices had closed, but root development was not eviden (6 years follow-up). In addition, teeth were not responsive to sensitivity testing. | No |

| Nosrat et al., 2011 | 36 | n=2 | Caries | Necrotic pulp with Symptomatic Apical Periodontitis | Teeth were asymptomatic, had healed periradicular lesions and demonstrated thickening of the dentinal walls (3–18 months follow-up). | N/A |

| Jung et al., 2011 | 107 | n=1 | Unknown | Previous Initiated Therapy with Chronic Apical Abscess | Tooth was asymptoamtic with resolution of periradicular lesion and sinus tract. There was evident development of the apical 1/3 that was found to be dettached from the main root. | N/A |

| Cehreli et al., 2011 | 49 | n=6 | Caries (n=6) | Pulp Necrosis with Symptomatic Apical Periodontitis | There was average of 7.7 % increase in root length and 26.5% root width increase. In addition, 33.3% (n=2) responded positively to sensitivity testing (12 months follow-up). | Yes |

| Torabinejad and Turman, 2011 | 43 | n=1 | Accidental extraction | N/A | There was evidence of resolution of apical lesion and symptoms, further root development and apical closure (5 1/2 month recall). | No |

| Kootor and Velmurugan, 2012 | 103 | n=1 | Trauma (complicated crown Fracture; tooth #7) | Pulp Necrosis and Symptomatic Apical Periodontitis | Tooth was asymptomatic (3 month recall); evidence of continued root developent and apical closure (1 year follow-up); further development was evident, but no positive respose to sensitivity tests were observed (3 and 5 years follow-up). | No |

| Jeeruphan et al., 2012 | 12 | n=20 | Trauma (n=7); Dens evaginatus (n=12); Caries (n=1) | Pulp Necrosis (n=20) with Symptomatic Apical Periodontitis (n=17) and Asymptomatic apical periodontitis (n=3) | There was resolution healing of apical periodontitis and detection of a 28.2% increase in root width, 14.9% increase in root length and 100% survival rate. On the other hand, teeth treated with Ca(OH)2 or MTA apexification procedures demonstrated no root development and a survival of 77.2% and 95%, respectively. | N/A |

| Shimizu et al., 2012 | 39 | n=1 | Trauma #9 (complicated crown fracture). | Symptomatic Irreversible Pulpitis with Normal Periradicular Tissues | Histological evaluation of the extracted tooth revealed a connective tissue that resembled pulp with with flattened cells surrounding the dentinal wall resembling odontoblasts. Also, cells of the Hertwig's epithelial root sheath could be seen surrounding the apical tissues. | N/A |

| Narayana et al., 2012 | 104 | n=1 | Dens invaginatus (tooth #7) | Pulp necrosis with Symptomatic Apical Periodontitis | Healing of periradicular lesion was detected (5 months follow-up), as well as formation of a dentinal bridge (12 months follow-up). No evident change in length or thickeness was seen (12 months follow-up). | No |

| Aggarwal et al., 2012 | 105 | n=1 | Trauma (tooth #8 and #9) | Pulp necrosis and Chronic Apical Absecess (Tooth #8 and #9) | Periapical healing, appreciable dentinal wall thickening and apical closure was detected when comparing tooth #9 (regenerative treatment) to tooth #8 (apexification treatmet) (2 year follow-up) | No |

| Miller et al., 2012 | 106 | n=1 | Trauma (avulsion). Avulsed tooth was kept in cold milk for 4.5 hrs prior to replantation. | Asymptomatic irreversible pulpitis and asymptomatic apical periodontitis | There was arrestment of the resorption process, periradicular healing and positive response to pulpal sensitivity tests (1–3 month follow-up). There was evident root development and apical closure while remaining asymptomatic without any other signs or symptoms of pathosis (18 months follow-up). | YES |

| Cehreli et al., 2012 | 107 | n=1 | Trauma (extrusive luxation injury) | N/A | There was periapical healing and evindece of continued root development (3 months). The tooth responded positively to cold tests (12 months follow-up) and EPT (18 months follow-up). | YES |

| Chen et al., 2012 | 50 | n=20 | Caries (n=3); Dens evaginatus (n=7); Trauma (n=10) | Pulp Necrosis (n=20) with Chronic Apical Abscess (n=11); Acute Apical Abscess (n=5) and Asymptomatic Apical Periodontitis (n=4). | There was evidence of periradicular healing with resolution of signs and symptoms of pathosis (100% of cases; n=20). There was evindece of continued root development at the follow-up visits in 15 cases (75%), whereas in 5 cases there was no further root development but apical closure was evident (25%). | N/A |

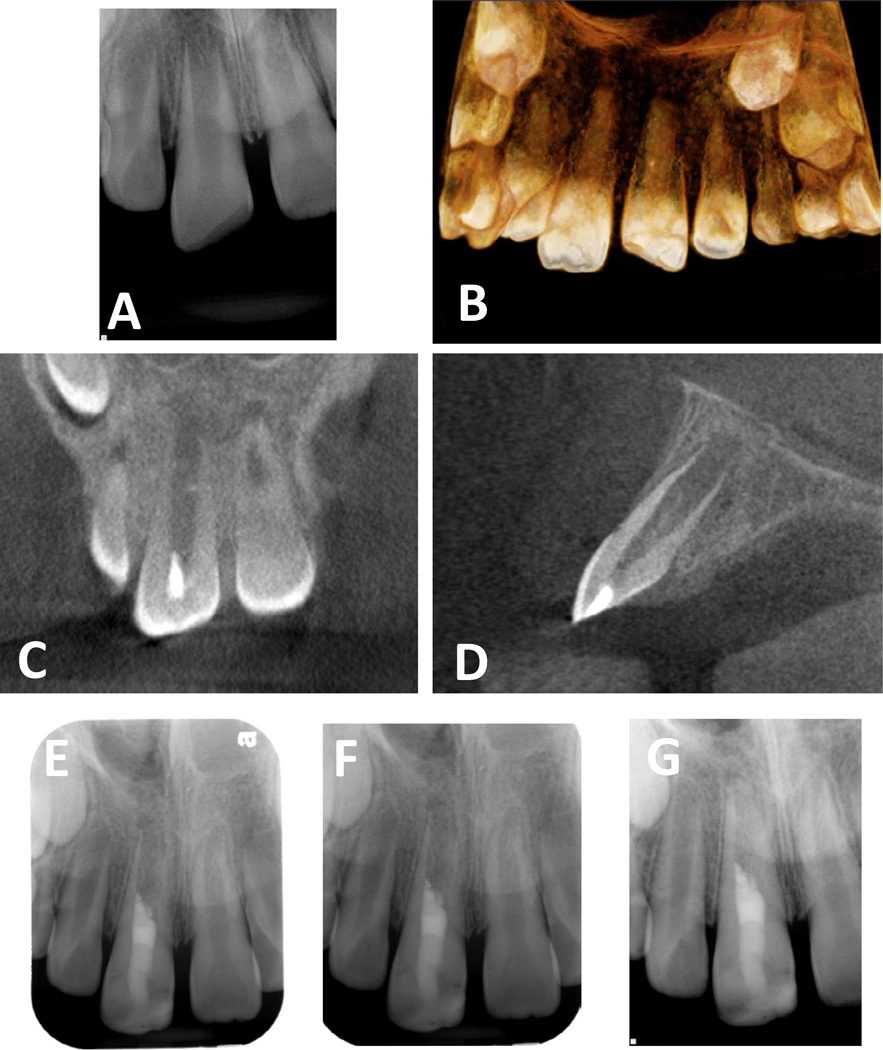

In San Antonio, our residents routinely provide regenerative treatment to immature permanent teeth with pulpal necrosis. The following describes a case with pulpal necrosis due to trauma. A 9-year-old male patient was to our graduate clinic for evaluation and treatment of tooth #8. The child had a traumatic injury to his maxilla, which caused an avulsion of tooth #G and lateral luxation of teeth #7, #8 and #9. Tooth #8 had uncomplicated crown fracture with loss of the incisal edge. According to the patient’s mother, the general dentist repositioned and splinted the permanent teeth. However, they never persuaded further treatment. Several months after treatment by the general dentist, the patient was taken by his mother to an emergency room at a local hospital, because he woke up with severe facial swelling on the right side extending up around his eye. Emergency treatment was then provided with incision and drainage above tooth #8 and placed on oral clindamycin. The patient presented to our clinic two days after the acute infection, with moderate to severe pain still present and significant peri-orbital swelling and swelling of the upper right lip with loss of labial fold. Purulence drainage was clinically observed from the sulcus between #8 and #9. It was not possible to perform pulpal responsivity tests due to the severe pain and inflammation in the area. A decision was made to treat #8 since it is most obvious etiology from both clinical and radiographic examination. The patient’s mother informed that we would thoroughly exam teeth #7 and #9 once the acute infection subsides. Radiographic findings (Fig 6A–D) indicated that teeth #7, #8 and #9 had open apices and tooth #8 had apical periodontitis. Clinically, all teeth were only partially erupted. Tooth #8 had a diagnosis of pulpal necrosis with acute apical abscess. Pulpal regeneration of tooth #8 was recommended. After reviewing the risks, benefits, and treatment options with the patient and his parent, an informed assent and consent were obtained for performing the recommended procedure on tooth #8. A topical anesthetic was applied to the mucosa before anesthetizing the tooth with 2% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine via labial and palatal infiltrations. After isolation with a rubber dam, a lingual access cavity was performed by using a Zeiss surgical microscope (Carl Zeiss Meditac Inc, Dublin, CA). Copious purulent and hemorrhagic drainage through the canal was observed upon access. The root canal system was mechanically debrided and copiously irrigated with 1.5% NaOCl followed by 17% EDTA. Several minutes were allowed for canal drainage between subsequent irrigations. The canal was then dried with paper points and calcium hydroxide was placed. The tooth was sealed with Cavit (ESPE, Chergy Pontoise, France).

Fig 6.

Example of a regenerative protocol applied to an immature permanent tooth with pulpal necrosis due to trauma. A: pre-operative image, B: Pre-operative cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) 3D view, C: pre-operative CBCT coronal view, D: pre-operative CBCT sagittal view, E: immediate post-operative radiograph, F: one month follow-up radiograph, G: six month follow-up radiograph

The patient returned 2 weeks later for continuation of treatment. The patient’s parent reported that he had no pain since last visit. The swelling was no longer noted. After applying 20% benzocaine topical anesthetic to the mucosa, 36.0 mg of mepivacaine was used for labial and palatal infiltrations. After isolation with rubber dam, the temporary restorative material was carefully removed. Copious irrigation with 20ml of 1.5% NaOCl followed by 10ml of 17% EDTA was performed. The canal was the dried with paper points. The pulp chamber space was then etched and coated with prime and bond (Optibond FL Prime™, Kerr Corporatino, Orange CA and Adhesive™ Kerr) to diminish possible staining. A thin watery mixture (92) of double antibiotic paste (DAP, Champs Pharmacy) containing metronidazole and ciprofloxacinin in a 1:1 ratio was then placed to below the CEJ level, a sterile sponge was packet in the canal and access cavity sealed with Cavit. A double antibiotic paste without minocycline was selected to reduce the risk of staining (109). The patient was schedule to return between 28 to 30 days to complete treatment.

At the final visit, the patient reported no pain or swelling. He was anesthetized with 2% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine and a rubber dam was placed. The temporary removed and canal was irrigated with 17% EDTA under microscopic view. The canal was then dried with paper points and intentional bleeding induced. A Colla-tape (Zimmer Dental, Carlsbad, CA, USA) matrix placed 4 to 5 mm below the CEJ level and an MTA (Pro-Root MTA; Dentsply Tulsa Dental Specialties, Tulsa, OK) barrier was placed. The access was then sealed with glass-ionomer (Fuji II™) and Built-It™ light cure – core material (Pentron, Orange, CA, USA). The patient’s parent was informed that follow-ups visits would necessary at 1, 3, 6 and 12 months. Patient was then referred to Postgraduate Pediatric Clinic for restoration of incisal edge fracture. Tooth #8 was restored with Z100™ (3M Espe Dental Products, USA) composite restoration; the occlusion was checked and post-op instructions provided (Fig 6E).

At the 1-month follow-up visit, tooth #8 and an evaluation of pulpal and periradicular status of teeth #7, 9, and 10 were conducted (Fig 6F). The patient’s mother reported that his son neither has had any discomfort nor history of pain since last visit. Tooth #8 did not respond to Endo Ice™ or an electric pulp tester (EPT). No discoloration was observed on tooth #8. All the other teeth did not respond to cold but they were positive to EPT. No mobility was observed and probing measurements were lass than 3mm on all teeth. The 6-month follow up visit was recommended.

At the 6-month follow-up visit, the patient’s mother reported that the patient had been asymptomatic since the last evaluation. No changes on medical history were recorded. All teeth tested (#7 through #10) did not respond to cold testing but were positive to EPT. No mobility was observed and probing depths were within normal limits. Tooth #8 was tested several times with cold and EPT with variations to test the patient’s reliability and the patient correctly reported positive response to EPT all times. Tooth #8 demonstrated continued root development with a substantial gain in length and wall thickness (Fig 6G). It was noted that tooth #8 is continuing to develop at a similar rate compared to tooth #9. The parents were informed of the need for a one year follow up examination.

Are we there yet? Considerations of current clinical protocols

Although the above review documents good clinical outcomes in the majority of studies treating the immature permanent tooth, there are several caveats. First, no randomized controlled trials have been conducted and therefore clinicians must rely on lower levels of clinical evidence. This is similar to numerous other examples of clinical decision points (e.g., selection of instrumentation methods, irrigation methods, obturation methods, antibiotics, etc), where clinicians must rely on the best available evidence, which in some cases ranges to the clinician’s expert opinion based upon preclinical studies. Second, the strongest evidence for success after regenerative treatment is based upon clinical outcomes (e.g., healing of apical periodontitis, continued radiographic root development). Third, current clinical protocols do not fully enact the triad of tissue engineering, and preclinical studies indicate that the addition of specific growth factors and scaffolds are necessary for anatomical regeneration of pulp tissue. Fourth, the etiology of pulp necrosis may be an important factor in dictating clinical outcomes after regenerative procedures. For example, a traumatic injury that disrupts Hertwig’s epithelial root or the apical papilla may result in aberrant root development (19, 110). Fifth, continued translational research is needed to continue to improve this method. This last caveat is the same as that across the entire field of dentistry – new methods must be constantly introduced and refined to allow clinicians to deliver better treatment for our patients.

Acknowledgment

Supported in part by R34 DE20864 and by NCATS 8UL1TR000149.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors deny conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Law A. Considerations for Revitalization/Regeneration Procedures. Journal of endodontics. 2013;39 doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2012.11.019. (in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glendor UWM, Andreasen JO. Classification, Epidemiology and Etiology. In: Andreasen JO, Andreasen FM, Andersson L, editors. Traumatic Injuries to the Teeth. 4th. ed. Oxford: Blackwell Munksgaard; 2007. pp. 217–254. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaba AD, Marechaux SC. A fourteen-year follow-up study of traumatic injuries to the permanent dentition. ASDC J Dent Child. 1989;56:417–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hecova H, Tzigkounakis V, Merglova V, Netolicky J. A retrospective study of 889 injured permanent teeth. Dent Traumatol. 2010;26:466–475. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2010.00924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borum MK, Andreasen JO. Therapeutic and economic implications of traumatic dental injuries in Denmark: an estimate based on 7549 patients treated at a major trauma centre. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2001;11:249–258. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-263x.2001.00277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andreasen JO, Borum MK, Jacobsen HL, Andreasen FM. Replantation of 400 avulsed permanent incisors. 1. Diagnosis of healing complications. Endodontics & dental traumatology. 1995;11:51–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.1995.tb00461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hargreaves KM, Giesler T, Henry M, Wang Y. Regeneration potential of the young permanent tooth: what does the future hold? Journal of endodontics. 2008;34:S51–S56. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kling M, Cvek M, Mejare I. Rate and predictability of pulp revascularization in therapeutically reimplanted permanent incisors. Endodontics & dental traumatology. 1986;2:83–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.1986.tb00132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andreasen JO, Farik B, Munksgaard EC. Long-term calcium hydroxide as a root canal dressing may increase risk of root fracture. Dent Traumatol. 2002;18:134–137. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-9657.2002.00097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hatibovic-Kofman S, Raimundo L, Zheng L, Chong L, Friedman M, Andreasen JO. Fracture resistance and histological findings of immature teeth treated with mineral trioxide aggregate. Dent Traumatol. 2008;24:272–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2007.00541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cvek M. Prognosis of luxated non-vital maxillary incisors treated with calcium hydroxide and filled with gutta-percha. A retrospective clinical study. Endodontics & dental traumatology. 1992;8:45–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.1992.tb00228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeeruphan T, Jantarat J, Yanpiset K, Suwannapan L, Khewsawai P, Hargreaves KM. Mahidol study 1: comparison of radiographic and survival outcomes of immature teeth treated with either regenerative endodontic or apexification methods: a retrospective study. Journal of endodontics. 2012;38:1330–1336. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2012.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmitt D, Lee J, Bogen G. Multifaceted use of ProRoot MTA root canal repair material. Pediatric dentistry. 2001;23:326–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bakland LK, Andreasen JO. Will mineral trioxide aggregate replace calcium hydroxide in treating pulpal and periodontal healing complications subsequent to dental trauma? A review. Dent Traumatol. 2012;28:25–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2011.01049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Damle SG, Bhattal H, Loomba A. Apexification of anterior teeth: a comparative evaluation of mineral trioxide aggregate and calcium hydroxide paste. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2012;36:263–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chala S, Abouqal R, Rida S. Apexification of immature teeth with calcium hydroxide or mineral trioxide aggregate: systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral surgery, oral medicine, oral pathology, oral radiology, and endodontics. 2011;112:e36–e42. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2011.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bose R, Nummikoski P, Hargreaves K. A retrospective evaluation of radiographic outcomes in immature teeth with necrotic root canal systems treated with regenerative endodontic procedures. Journal of endodontics. 2009;35:1343–1349. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murray PE, Garcia-Godoy F, Hargreaves KM. Regenerative endodontics: a review of current status and a call for action. Journal of endodontics. 2007;33:377–390. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andreasen JO. Pulp and periodontal tissue repair - regeneration or tissue metaplasia after dental trauma. A review. Dent Traumatol. 2012;28:19–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2011.01058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andreasen JO, Bakland LK. Pulp regeneration after non-infected and infected necrosis, what type of tissue do we want? A review. Dent Traumatol. 2012;28:13–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2011.01057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nygaard-Østby B. The role of the blood clot in endodontic therapy. An experimental histologic study. Acta Odont Scand. 1961;19:323–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nygaard-Østby B, Hjortdal O. Tissue formation in the root canal following pulp removal. Scandinavian journal of dental research. 1971;79:333–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1971.tb02019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Horsted P, Nygaard-Ostby B. Tissue formation in the root canal after total pulpectomy and partial root filling. Oral surgery, oral medicine, and oral pathology. 1978;46:275–282. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(78)90203-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nevins A, Finkelstein F, Laporta R, Borden BG. Induction of hard tissue into pulpless open-apex teeth using collagen-calcium phosphate gel. Journal of endodontics. 1978;4:76–81. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(78)80263-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nevins AJ, Finkelstein F, Borden BG, Laporta R. Revitalization of pulpless open apex teeth in rhesus monkeys, using collagen-calcium phosphate gel. Journal of endodontics. 1976;2:159–165. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(76)80058-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rule DC, Winter GB. Root growth and apical repair subsequent to pulpal necrosis in children. Br Dent J. 1966;120:586–590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iwaya SI, Ikawa M, Kubota M. Revascularization of an immature permanent tooth with apical periodontitis and sinus tract. Dent Traumatol. 2001;17:185–187. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-9657.2001.017004185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Banchs F, Trope M. Revascularization of immature permanent teeth with apical periodontitis: new treatment protocol? Journal of endodontics. 2004;30:196–200. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200404000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chueh LH, Huang GT. Immature teeth with periradicular periodontitis or abscess undergoing apexogenesis: a paradigm shift. Journal of endodontics. 2006;32:1205–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petrino JA. Revascularization of necrotic pulp of immature teeth with apical periodontitis. Northwest dentistry. 2007;86:33–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thibodeau B, Trope M. Pulp revascularization of a necrotic infected immature permanent tooth: case report and review of the literature. Pediatric dentistry. 2007;29:47–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chueh LH, Ho YC, Kuo TC, Lai WH, Chen YH, Chiang CP. Regenerative endodontic treatment for necrotic immature permanent teeth. Journal of endodontics. 2009;35:160–164. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cotti E, Mereu M, Lusso D. Regenerative treatment of an immature, traumatized tooth with apical periodontitis: report of a case. Journal of endodontics. 2008;34:611–616. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Geisler TM. Clinical considerations for regenerative endodontic procedures. Dent Clin North Am. 2012;56:603–626. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2012.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Law AS. Outcomes of regenerative endodontic procedures. Dent Clin North Am. 2012;56:627–637. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nosrat A, Seifi A, Asgary S. Regenerative endodontic treatment (revascularization) for necrotic immature permanent molars: a review and report of two cases with a new biomaterial. Journal of endodontics. 2011;37:562–567. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Petrino JA, Boda KK, Shambarger S, Bowles WR, McClanahan SB. Challenges in Regenerative Endodontics: A Case Series. Journal of endodontics. 2010;36:536–541. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shah N, Logani A, Bhaskar U, Aggarwal V. Efficacy of revascularization to induce apexification/apexogensis in infected, nonvital, immature teeth: a pilot clinical study. Journal of endodontics. 2008;34:919–925. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.05.001. Discussion 1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shimizu E, Jong G, Partridge N, Rosenberg PA, Lin LM. Histologic observation of a human immature permanent tooth with irreversible pulpitis after revascularization/regeneration procedure. Journal of endodontics. 2012;38:1293–1297. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2012.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shin SY, Albert JS, Mortman RE. One step pulp revascularization treatment of an immature permanent tooth with chronic apical abscess: a case report. International endodontic journal. 2009;42:1118–1126. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2009.01633.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thomson A, Kahler B. Regenerative endodontics--biologically-based treatment for immature permanent teeth: a case report and review of the literature. Aust Dent J. 2010;55:446–452. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2010.01268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Torabinejad M, Faras H. A clinical and histological report of a tooth with an open apex treated with regenerative endodontics using platelet-rich plasma. Journal of endodontics. 2012;38:864–868. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2012.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Torabinejad M, Turman M. Revitalization of tooth with necrotic pulp and open apex by using platelet-rich plasma: a case report. Journal of endodontics. 2011;37:265–268. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Garcia-Godoy F, Murray PE. Recommendations for using regenerative endodontic procedures in permanent immature traumatized teeth. Dent Traumatol. 2012;28:33–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2011.01044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jung IY, Lee SJ, Hargreaves KM. Biologically based treatment of immature permanent teeth with pulpal necrosis: a case series. Journal of endodontics. 2008;34:876–887. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reynolds K, Johnson JD, Cohenca N. Pulp revascularization of necrotic bilateral bicuspids using a modified novel technique to eliminate potential coronal discolouration: a case report. International endodontic journal. 2009;42:84–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2008.01467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ding RY, Cheung GS, Chen J, Yin XZ, Wang QQ, Zhang CF. Pulp revascularization of immature teeth with apical periodontitis: a clinical study. Journal of endodontics. 2009;35:745–749. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mendoza AM, Reina ES, Garcia-Godoy F. Evolution of apical formation on immature necrotic permanent teeth. Am J Dent. 2010;23:269–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cehreli ZC, Isbitiren B, Sara S, Erbas G. Regenerative endodontic treatment (revascularization) of immature necrotic molars medicated with calcium hydroxide: a case series. Journal of endodontics. 2011;37:1327–1330. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2011.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen MY, Chen KL, Chen CA, Tayebaty F, Rosenberg PA, Lin LM. Responses of immature permanent teeth with infected necrotic pulp tissue and apical periodontitis/abscess to revascularization procedures. International endodontic journal. 2012;45:294–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2011.01978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Albrecht J, Meves A, Bigby M. A survey of case reports and case series of therapeutic interventions in the Archives of Dermatology. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:592–597. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.04031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Friedman S. Outcome of endodontic surgery: a meta-analysis of the literature-part 1: comparison of traditional root-end surgery and endodontic microsurgery. Journal of endodontics. 2011;37:577–578. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2011.01.020. author reply 8–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Torabinejad M, Corr R, Handysides R, Shabahang S. Outcomes of nonsurgical retreatment and endodontic surgery: a systematic review. Journal of endodontics. 2009;35:930–937. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Barkhordarian A, Hacker B, Chiappelli F. Dissemination of evidence-based standards of care. Bioinformation. 2011;7:315–319. doi: 10.6026/007/97320630007315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bauer J, Spackman S, Chiappelli F, Prolo P. Evidence-based decision making in dental practice. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2005;5:125–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jebdp.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Langer R, Vacanti JP. Tissue engineering. Science. 1993;260:920–926. doi: 10.1126/science.8493529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Egusa H, Sonoyama W, Nishimura M, Atsuta I, Akiyama K. Stem cells in dentistry - Part I: Stem cell sources. J Prosthodont Res. 2012;56:151–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jpor.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Huang GT, Gronthos S, Shi S. Mesenchymal stem cells derived from dental tissues vs. those from other sources: their biology and role in regenerative medicine. Journal of dental research. 2009;88:792–806. doi: 10.1177/0022034509340867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Huang GT, Sonoyama W, Liu Y, Liu H, Wang S, Shi S. The hidden treasure in apical papilla: the potential role in pulp/dentin regeneration and bioroot engineering. Journal of endodontics. 2008;34:645–651. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sonoyama W, Liu Y, Fang D, Yamaza T, Seo BM, Zhang C, Liu H, Gronthos S, Wang CY, Shi S, Wang S. Mesenchymal stem cell-mediated functional tooth regeneration in swine. PLoS ONE. 2006;1:e79. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mao JJ, Robey PG, Prockop DJ. Stem cells in the face: tooth regeneration and beyond. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11:291–301. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tziafas D, Kodonas K. Differentiation potential of dental papilla, dental pulp, and apical papilla progenitor cells. Journal of endodontics. 2010;36:781–789. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nakashima M, Akamine A. The application of tissue engineering to regeneration of pulp and dentin in endodontics. Journal of endodontics. 2005;31:711–718. doi: 10.1097/01.don.0000164138.49923.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Alongi DJ, Yamaza T, Song Y, Fouad AF, Romberg EE, Shi S, Tuan RS, Huang GT. Stem/progenitor cells from inflamed human dental pulp retain tissue regeneration potential. Regen Med. 2010;5:617–631. doi: 10.2217/rme.10.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liao J, Al Shahrani M, Al-Habib M, Tanaka T, Huang GT. Cells isolated from inflamed periapical tissue express mesenchymal stem cell markers and are highly osteogenic. Journal of endodontics. 2011;37:1217–1224. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2011.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lovelace TW, Henry MA, Hargreaves KM, Diogenes A. Evaluation of the delivery of mesenchymal stem cells into the root canal space of necrotic immature teeth after clinical regenerative endodontic procedure. Journal of endodontics. 2011;37:133–138. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wei X, Ling J, Wu L, Liu L, Xiao Y. Expression of mineralization markers in dental pulp cells. Journal of endodontics. 2007;33:703–708. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li L, Zhu YQ, Jiang L, Peng W, Ritchie HH. Hypoxia promotes mineralization of human dental pulp cells. Journal of endodontics. 2011;37:799–802. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2011.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Huang GT, Shagramanova K, Chan SW. Formation of odontoblast-like cells from cultured human dental pulp cells on dentin in vitro. Journal of endodontics. 2006;32:1066–1073. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sun HH, Jin T, Yu Q, Chen FM. Biological approaches toward dental pulp regeneration by tissue engineering. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2011;5:e1–e16. doi: 10.1002/term.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Galler KM, D'Souza RN, Federlin M, Cavender AC, Hartgerink JD, Hecker S, Schmalz G. Dentin conditioning codetermines cell fate in regenerative endodontics. Journal of endodontics. 2011;37:1536–1541. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2011.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Prescott RS, Alsanea R, Fayad MI, Johnson BR, Wenckus CS, Hao J, John AS, George A. In vivo generation of dental pulp-like tissue by using dental pulp stem cells, a collagen scaffold, and dentin matrix protein 1 after subcutaneous transplantation in mice. Journal of endodontics. 2008;34:421–426. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kim SG, Zhou J, Solomon C, Zheng Y, Suzuki T, Chen M, Song S, Jiang N, Cho S, Mao JJ. Effects of growth factors on dental stem/progenitor cells. Dent Clin North Am. 2012;56:563–575. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Discher DE, Mooney DJ, Zandstra PW. Growth factors, matrices, and forces combine and control stem cells. Science. 2009;324:1673–1677. doi: 10.1126/science.1171643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wei X, Liu L, Zhou X, Zhang F, Ling J. The effect of matrix extracellular phosphoglycoprotein and its downstream osteogenesis-related gene expression on the proliferation and differentiation of human dental pulp cells. Journal of endodontics. 2012;38:330–338. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2011.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kim JK, Shukla R, Casagrande L, Sedgley C, Nor JE, Baker JR, Jr, Hill EE. Differentiating dental pulp cells via RGD-dendrimer conjugates. Journal of dental research. 2010;89:1433–1438. doi: 10.1177/0022034510384870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Paranjpe A, Smoot T, Zhang H, Johnson JD. Direct contact with mineral trioxide aggregate activates and differentiates human dental pulp cells. Journal of endodontics. 2011;37:1691–1695. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2011.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Galler KM, D'Souza RN, Hartgerink JD, Schmalz G. Scaffolds for dental pulp tissue engineering. Adv Dent Res. 2011;23:333–339. doi: 10.1177/0022034511405326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Huang GT, Lin LM. Letter to the editor: comments on the use of the term "revascularization" to describe root regeneration. Journal of endodontics. 2008;34:511. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.02.009. author reply -2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Trope M. Regenerative potential of dental pulp. J Endod. 2008;34:S13–S17. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Huang GT, Yamaza T, Shea LD, Djouad F, Kuhn NZ, Tuan RS, Shi S. Stem/Progenitor cell-mediated de novo regeneration of dental pulp with newly deposited continuous layer of dentin in an in vivo model. Tissue engineering. 2010;16:605–615. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2009.0518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Iohara K, Nakashima M, Ito M, Ishikawa M, Nakasima A, Akamine A. Dentin regeneration by dental pulp stem cell therapy with recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein 2. Journal of dental research. 2004;83:590–595. doi: 10.1177/154405910408300802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kodonas K, Gogos C, Papadimitriou S, Kouzi-Koliakou K, Tziafas D. Experimental formation of dentin-like structure in the root canal implant model using cryopreserved swine dental pulp progenitor cells. Journal of endodontics. 2012;38:913–919. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Iohara K, Imabayashi K, Ishizaka R, Watanabe A, Nabekura J, Ito M, Matsushita K, Nakamura H, Nakashima M. Complete pulp regeneration after pulpectomy by transplantation of CD105+ stem cells with stromal cell-derived factor-1. Tissue engineering. 2011;17:1911–1920. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2010.0615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ishizaka R, Iohara K, Murakami M, Fukuta O, Nakashima M. Regeneration of dental pulp following pulpectomy by fractionated stem/progenitor cells from bone marrow and adipose tissue. Biomaterials. 2012;33:2109–2118. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.11.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nakashima M, Iohara K. Regeneration of dental pulp by stem cells. Adv Dent Res. 2011;23:313–319. doi: 10.1177/0022034511405323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Anitua E, Sanchez M, Nurden AT, Nurden P, Orive G, Andia I. New insights into and novel applications for platelet-rich fibrin therapies. Trends in biotechnology. 2006;24:227–234. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2006.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Smith AJ. Vitality of the dentin-pulp complex in health and disease: growth factors as key mediators. Journal of Dental Education. 2003;67:678–689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cooper PR, McLachlan JL, Simon S, Graham LW, Smith AJ. Mediators of inflammation and regeneration. Adv Dent Res. 2011;23:290–295. doi: 10.1177/0022034511405389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Arora NS, Ramanayake T, Ren YF, Romanos GE. Platelet-rich plasma: a literature review. Implant Dent. 2009;18:303–310. doi: 10.1097/ID.0b013e31819e8ec6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Alsousou J, Thompson M, Hulley P, Noble A, Willett K. The biology of platelet-rich plasma and its application in trauma and orthopaedic surgery: a review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91:987–996. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B8.22546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Trevino EG, Patwardhan AN, Henry MA, Perry G, Dybdal-Hargreaves N, Hargreaves KM, Diogenes A. Effect of irrigants on the survival of human stem cells of the apical papilla in a platelet-rich plasma scaffold in human root tips. Journal of endodontics. 2011;37:1109–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ruparel NB, Teixeira FB, Ferraz CC, Diogenes A. Direct effect of intracanal medicaments on survival of stem cells of the apical papilla. Journal of endodontics. 2012;38:1372–1375. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2012.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Thibodeau B, Teixeira F, Yamauchi M, Caplan DJ, Trope M. Pulp revascularization of immature dog teeth with apical periodontitis. Journal of endodontics. 2007;33:680–689. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ritter AL, Ritter AV, Murrah V, Sigurdsson A, Trope M. Pulp revascularization of replanted immature dog teeth after treatment with minocycline and doxycycline assessed by laser Doppler flowmetry, radiography, and histology. Dent Traumatol. 2004;20:75–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-4469.2004.00225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wang X, Thibodeau B, Trope M, Lin LM, Huang GT. Histologic characterization of regenerated tissues in canal space after the revitalization/revascularization procedure of immature dog teeth with apical periodontitis. Journal of endodontics. 2010;36:56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zuong XY, Yang YP, Chen WX, Zhang YJ, Wen CM. Pulp revascularization of immature anterior teeth with apical periodontitis. Hua Xi Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2010;28:672–674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.da Silva LA, Nelson-Filho P, da Silva RA, Flores DS, Heilborn C, Johnson JD, Cohenca N. Revascularization and periapical repair after endodontic treatment using apical negative pressure irrigation versus conventional irrigation plus triantibiotic intracanal dressing in dogs' teeth with apical periodontitis. Oral surgery, oral medicine, oral pathology, oral radiology, and endodontics. 2010;109:779–787. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Scarparo RK, Dondoni L, Bottcher DE, Grecca FS, Rockenbach MI, Batista EL., Jr Response to intracanal medication in immature teeth with pulp necrosis: an experimental model in rat molars. Journal of endodontics. 2011;37:1069–1073. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2011.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Buhrley M, Corr R, Shabahang S, Torabinejad M. Identification of tissues formed after pulp revascularization in a ferret model. Journal of endodontics. 2011;37:29. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2010.10.011. (abstract) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Brynolf I. A histological and roentgenological study of the periapical regions of human upper incisors. Odontologisk revy. 1967;18(Suppl 11):1–176. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Green TL, Walton RE, Taylor JK, Merrell P. Radiographic and histologic periapical findings of root canal treated teeth in cadaver. Oral surgery, oral medicine, oral pathology, oral radiology, and endodontics. 1997;83:707–711. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(97)90324-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Barthel CR, Zimmer S, Trope M. Relationship of radiologic and histologic signs of inflammation in human root-filled teeth. Journal of endodontics. 2004;30:75–79. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200402000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kottoor J, Velmurugan N. Revascularization for a necrotic immature permanent lateral incisor: a case report and literature review. International journal of paediatric dentistry / the British Paedodontic Society [and] the International Association of Dentistry for Children. 2012 doi: 10.1111/ipd.12000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Narayana P, Hartwell GR, Wallace R, Nair UP. Endodontic clinical management of a dens invaginatus case by using a unique treatment approach: a case report. Journal of endodontics. 2012;38:1145–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2012.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Aggarwal V, Miglani S, Singla M. Conventional apexification and revascularization induced maturogenesis of two non-vital, immature teeth in same patient: 24 months follow up of a case. Journal of conservative dentistry : JCD. 2012;15:68–72. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.92610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Miller EK, Lee JY, Tawil PZ, Teixeira FB, Vann WF., Jr Emerging therapies for the management of traumatized immature permanent incisors. Pediatric dentistry. 2012;34:66–69. [Case Reports]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Cehreli ZC, Sara S, Aksoy B. Revascularization of immature permanent incisors after severe extrusive luxation injury. J Can Dent Assoc. 2012;78:c4. [Case Reports]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kim JH, Kim Y, Shin SJ, Park JW, Jung IY. Tooth discoloration of immature permanent incisor associated with triple antibiotic therapy: a case report. Journal of endodontics. 2010;36:1086–1091. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2010.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Jung IY, Kim ES, Lee CY, Lee SJ. Continued development of the root separated from the main root. Journal of endodontics. 2011;37:711–714. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2011.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]