Abstract

Background:

Focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST) is an important skill during trauma resuscitation. Use of point of care ultrasound among the trauma team working in emergency care settings is lacking in India.

Objective:

To determine the accuracy of FAST done by nonradiologists (NR) when compared to radiologists during primary survey of trauma victims in the emergency department of a level 1 trauma center in India.

Materials and Methods:

A prospective study was done during primary survey of resuscitation of nonconsecutive patients in the resuscitation bay. The study subjects included NR such as one consultant emergency medicine, two medicine residents, one orthopedic resident and one surgery resident working as trauma team. These subjects underwent training at 3-day workshop on emergency sonography and performed 20 supervised positive and negative scans for free fluid. The FAST scans were first performed by NR and then by radiology residents (RR). The performers were blinded to each other's sonography findings. Computed tomography (CT) and laparotomy findings were used as gold standard whichever was feasible. Results were compared between both the groups. Intraobserver variability among NR and RR were noted.

Results:

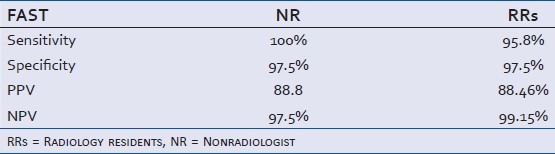

Out of 150 scans 144 scans were analyzed. Mean age of the patients was 28 [1-70] years. Out of 24 true positive patients 18 underwent CT scan and exploratory laparotomies were done in six patients. Sensitivity of FAST done by NR and RR were 100% and 95.6% and specificity was 97.5% in both groups. Positive predictive value among NR and RR were 88.8%, 88.46% and negative predictive value were 97.5% and 99.15%. Intraobserver performance variation ranged from 87 to 97%.

Conclusion:

FAST performed by NRs is accurate during initial trauma resuscitation in the emergency department of a level 1 trauma center in India.

Keywords: FAST, trauma, radiologist, nonradiologists

INTRODUCTION

Trauma is one of the leading causes of death in India and has a dubious distinction of worst road traffic crash rate worldwide. As per WHO and National Crime Bureau records more than 1,30,000 people die every year due to road traffic crash, and hospitalization of 1.5 million people resulting in an estimated economic loss of 3% of GDP to the country. Lack of trained emergency care providers at different tiers of heath care adds up to the existing problem of suboptimal infrastructure. Emergency Medicine and Trauma surgery as a specialty is in its infancy in India. Advance Trauma Life support (ATLS) and similar courses has started recently. Focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST) examination is done by radiologist in India. Point of care (POC) ultrasound (USG) in emergency setting is naive in India. In setting up of a new emergency department (ED) protocols of a level 1 trauma center, the research group underwent POC ultrasound training and the study was conducted to determine the accuracy of FAST done by nonradiologists (NR) and its comparative analysis with radiologists in emergency department of a level 1 trauma center of India.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

It was a prospective study done during primary survey of resuscitation of nonconsecutive patients in the resuscitation bay of emergency department (ED) of trauma center, All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) with an annual ED visit of 50,000 patients. The study was conducted over a period of 7 months. The study subjects included one consultant emergency medicine (EM) and two medicine residents, one orthopedic resident and one surgery resident posted in ED as emergency care providers. They were trained in emergency sonography on a 3-day workshop on conducted by ‘Indo-US collaborative in Emergency and trauma’ at AIIMS trauma center in February 2008 and performed 20 supervised positive and negative FAST scans for free fluid before recruitment to the study. Patient in whom performing FAST would potentially delay emergency procedures (e.g., penetrating abdominal trauma) were excluded. The FAST scans were first performed by the NR and then by radiology resident (RR) who had already done 3 years of postgraduate training in radiology. Both were blinded to each other's ultrasound findings. CT scan and laparotomy findings were used as gold standard whichever was feasible. Results were compared between both groups. Intraobserver variability was evaluated between NR and RR. Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive value of FAST done by NR and RR were noted. Statistical analysis was done by SPSS version 16.

EXAMINATION TECHNIQUE

Patient position

Supine with arms abducted slightly or above the head

Probe and scanner setting

A low frequency (5-2 MHz) curvilinear probe was used with a focused depth and depth setting according to the patient's body habitus and initial images obtained.

The 5 views

First, the subxiphoid four-chamber view with the probe placed in subxiphoid region directed toward the (L) shoulder with the probe pointer toward (R) axial of the patient. The probe was angled to approximately 40 degree to the horizontal of the heart was used to examine for pericardial fluid. Change of angulations and sideways movements were made to get better view.

Next, for focussing on Morrison's pouch and right lung base, probe was placed parallel and between the ribs where the costal margin meets the mid-axillary line on the right of the patient with probe pointer toward head end. The view obtained utilizes the liver as an acoustic window and demonstrates right kidney, liver, diaphragm (highly echogenic) and right lung base. Probe sweeped antero-posteriorly and angulations changed until a clear view of Morrison's pouch not obtained. Free fluid appeared as black stripe in Morrison's pouch.

The Linorenal interface and left lung base: The probe was placed on the left side at 9th-11th rib level in posterior axillary line with the with probe pointer toward head end. Probe sweeped antero-posteriorly and angulations changed until a clear view of left kidney, spleen, diaphragm and left lung base not obtained. Free fluid appeared as black stripe in the Lino-renal interface or between the spleen and the diaphragm.

The Pelvic (sagittal view): The probe was placed in midline just above the pubis and was angled caudally at 45 degrees into the pelvis with probe pointer toward head end. The view demonstrates a coronal section of bladder and pelvic organs. Free fluid appeared as black stripe around the bladder or behind it (pouch of Douglas).

The Pelvic (transverse view): The view was obtained by rotating the probe through 90 degrees while maintaining contact with the abdominal wall and was angled into the pelvis with probe pointer toward patient's right. Bladder and pelvic organs identified in coronal section. Free fluid appeared as black stripe around the bladder or behind it (pouch of Douglas).

RESULTS

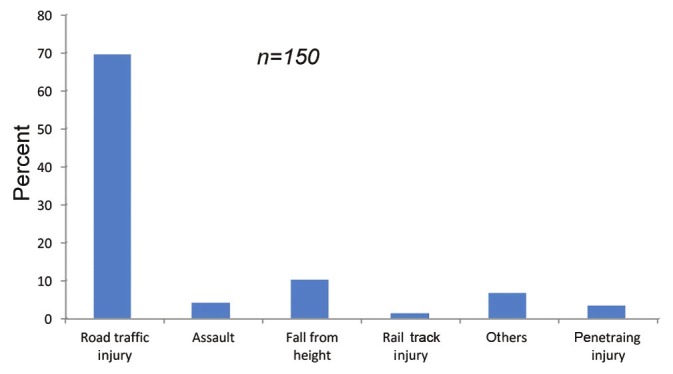

Fifty thousand patients visit ED annually; out of which 7-10% were major trauma patients. 86.6% were males and 13.4% were females. Mean age of the patients were 28 [1-70] yrs. Seventeen out of 150 patients were in pediatric age group (≤12 yrs). The mechanism of injury is shown Figure 1. One hundred and forty-six out of 150 patients had systolic blood pressure (SBP) of >90 mmHg, fours patients had SBP < 90 mmHg.

Figure 1.

Mechanism of injury

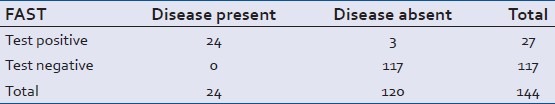

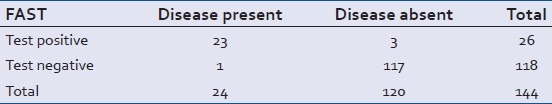

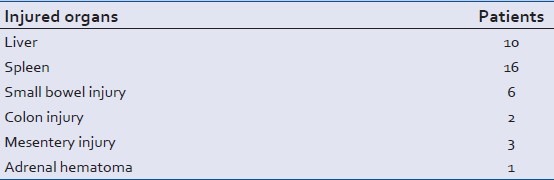

FAST scans (n = 150) were performed in each NR and RR group. Six patients of penetrating trauma were excluded from final analysis. Observations of FAST results among NR and RR were analyzed [Tables 1 and 2]. Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive value of FAST done by NR and RR were shown in [Table 3]. Intraobserver performance variation ranged from 87 to 97%. Out of 24 true positive patients 18 underwent CT scan and exploratory laparotomy was done in six patients. Four out of six patients who underwent therapeutic laparotomy had SBP < 90 mmHg. Details of organ injuries have been depicted in Table 4. False positive cases were observed and managed conservatively.

Table 1.

Observations of nonradiologists (n = 150)

Table 2.

Observations of radiology residents (n = 150)

Table 3.

Comparative FAST observations among NR and RRs (n = 150)

Table 4.

Details of organ injuries (n = 24 patients)

DISCUSSION

FAST is a rapid, repeatable noninvasive bedside method that was designed to answer one single question: Whether free fluid is present in the peritoneal and pericardial cavity. It has been a valuable investigation for the initial assessment of blunt abdominal trauma as shown in large series from several North America trauma centers.[1–4] Usually it is done as part of trauma resuscitation by radiologists in trauma team or emergency physicians. Studies reported a sensitivity of 80–88% and specificity of 90-99% among NR's ability to detect hemoperitoneum using the FAST technique.[5–8]

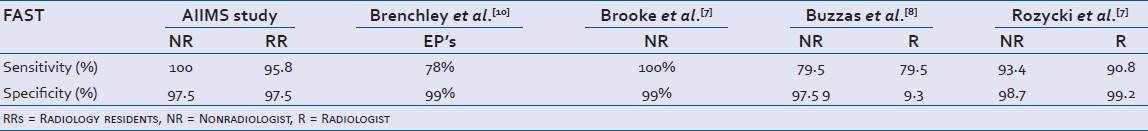

Currently ultrasound is being done by radiologist even in emergency setting in India. Jehangir et al. from India reported sensitivity of 91% and specificity of 100% in identifying fluid by radiologist in blunt trauma abdomen.[9] The present study reported a sensitivity of 100% with a specificity of 97.5% among NR and 95.8% sensitivity with 97.5% specificity among RR. They can be compared against trained radiologist as well as international results [Table 5].[7,8,10] The comparatively small number of patients with hemoperitoneum in the series may account for the high sensitivity in our study. The number of patients in the study, although small by international standards, is a representative sample size.

Table 5.

Comparison of FAST for blunt trauma with International studies

Gaarder et al. reported sensitivity and specificity of 62% and 96%, respectively, with an overall accuracy of 88% among unstable patients (hypotension, tachycardia and acidosis). The positive predictive value and negative predictive value were 84% and 88%, respectively.[11] The present study had only four patients with hypotension with FAST positive reported by NR and RR. All four patients had positive CT finding and underwent therapeutic laparotomy. We cannot draw any meaningful conclusion due to small number of patients.

FAST has previously been compared favorably to CT and DPL in the investigation of blunt abdominal injury.[8,12] CT is currently accepted as the gold standard for the investigation of the trauma patient. In addition to providing evidence of bleeding it gives detailed anatomical information of injuries. It is associated with a sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 98%.[13] However, it is not apt for the unstable injured patient. DPL is a sensitive investigation for abdominal bleeding[14] and previously the gold standard for the abdominal investigation of the unstable trauma patient. It has fallen from favor because of its invasive nature and the high incidence of nontherapeutic laparotomy after a positive result.[15]

Previous studies looking at FAST in penetrating trauma have been disappointing. Kahdi[16] evaluated 75 patients with penetrating injuries and reported 22 false negative scans and a sensitivity of only 46%.The limited number of patients with penetrating injuries in our study which were excluded precludes meaningful conclusions.

Limitations of a negative FAST examination have been recognized[17,18] and a negative FAST should be repeated at an interval of six hours[19] as was done in our patients. Patients with a negative scan were observed clinically and none of this group developed abdominal related complications. Its analysis was not in purview of the trial protocol.

Boulanger had previously reported that in cardiovascular unstable patients FAST will reveal intra-abdominal blood within 20 seconds.[20,21] All the FAST scans in this series were completed within a 4-minute time period. The horizontal organisation of the trauma team allowed FAST to proceed without delay or disruption in the flow of the resuscitation. No attempt was made to differentiate the length of time taken for positive or negative FAST in this study.

The issue of training for NRs in POC USG remains contentious. Previous qualitative study done at this center during a 4-day Indo-US Emergency Ultrasound workshop reported that 24 (75%) participants had no prior experience, five (16%) had some experience, and three (9%) had significant experience with emergency ultrasound. During the practical examination, 38 out of 42 participants (90%) were able to identify Morison's pouch on the FAST examination.[22]

The present study subjects included NRs such as consultant emergency medicine, medicine residents, orthopaedic resident and surgery resident working as emergency care givers during their posting in the ED. They underwent training at 3-day workshop on emergency sonography which included didactic, hands on experience. They performed 20 supervised positive and negative FAST scans for identifying free fluid before recruitment to the study. This is in line with the American College of Surgeons recommendations of an 8-hour trauma US course, which has been shown to be adequate for the successful performance of the technique,[10] followed by a minimum of 10 proctored scans. Review of all the recorded images by the most experienced investigator and regular feedback was used as an effective quality assurance program.

During the beginning of the study the scan was done by a trained emergency medicine consultant, who was the team leader otherwise not involved in the resuscitation of the patient. As the study progressed it was often difficult to find a doctor available to scan because of the workload within the department. This is the reason for sampling of convenience. It also proved impossible to blind members of the trauma team to the results of the scan; however results were blinded to the radiologist. There was variation in the number of scans undertaken by individual NR sonographers. This was partly due to individual enthusiasm for the technique. Trained residents of surgery and orthopaedics recruited for the study were rotational staff as they were posted to the ED for a period of two month but medicine resident was permanent. Rotational residents were absent from ED for 3 months during the study period. There is no evidence from our data to suggest that there was significant skill attrition during this time and there was a high level of agreement among NR and RR. Similar concerns were reported by Brenchley et al.[23] FAST can be performed by adequately trained emergency care providers and it should be adopted as an adjunct to the clinical assessment of abdominal trauma.

Limitation: Small Sample size. Study does not include penetrating trauma

CONCLUSIONS

FAST performed by NRs is accurate during initial trauma resuscitation in the emergency department of a level 1 trauma center in India.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rozycki GS, Ochsner MG, Jaffin JH. Prospective evaluation of surgeons’use of ultrasound in the evaluation of trauma patients. J Trauma. 1993;34:516–27. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199304000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dolich MO, McKenney MG, Varela JE. 2576 ultrasounds for blunt abdominal trauma. J Trauma. 2001;50:108–12. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200101000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sloan JP, Lalanda M, Brenchley J. Developing the role of emergency medicine ultrasonography. The Leeds experience. Emerg Med J. 2002;19:A63. [Google Scholar]

- 4.McKenney MG, Martin L, Lentz K, lopez C, Sleeman D, Aristide G, et al. 1000 consecutive ultrasounds for blunt abdominal trauma. J Trauma. 1996;40:607–12. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199604000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rozycki GS, Ochsner MG, Schmidt JA, Frankel HL, Davis TP, Wang D, et al. A prospective study of surgeon performed ultrasound as the primary adjuvant modality for injured patient assessment. J Trauma. 1995;39:492–500. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199509000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rozycki GS, Shackford SR. Trauma ultrasound for surgeons. In: Staren ED, editor. Ultrasound for the Surgeon. New York: Lippincott-Raven; 1997. pp. 120–35. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brooks A, Davies B, Smethhurst M, Connolly J. Prospective evaluation of non-radiologist performed emergency abdominal ultrasound for haemo-peritoneum. Emerg Med J. 2004;21:e5. doi: 10.1136/emj.2003.006932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buzzas GR, Kern SJ, Smith RS, Harrison PB, Helmer SD, Reed JA. A comparison of sonographic examinations for trauma performed by surgeons and radiologists. J Trauma. 1998;44:604–8. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199804000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jehangir B, Bhatt A, Nazir A. Role of ultrasonography in blunt abdominal trauma: A retrospective study. JK Pract. 2003;10:118–9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomas B, Falcone RE, Vasquez D, Santanello S, Townsend M, Hockenberry S, et al. Ultrasound evaluation of blunt abdominal trauma: Program implementation, initial experience, and learning curve. J Trauma. 1997;42:384–90. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199703000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaarder C, Kroepelien CF, Loekke R, Hestnes M, Dormage B, Naess AP. Ultrasound performed by radiologists-confirming the truth about fast in trauma. J Trauma. 2009;67:323–9. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181a4ed27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKenney M, Lentz K, Nunez D, Sosa JL, Sleeman D, Axelrad A, et al. Can ultrasound replace diagnostic peritoneal lavage in the assessment of blunt trauma. J Trauma. 1994;37:439–41. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199409000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boulanger BR, McLellan BA, Brenneman FD, Ochoa J, Kirkpatrick AW. Prospective evidence of superiority of a sonography based algorithm in the assessment of blunt abdominal injury. J Trauma. 1999;47:632–7. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199910000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Catre MG. Diagnositic peritoneal lavage versus abdominal computed tomography in blunt abdominal trauma: A review of prospective studies. Can J Surg. 1995;38:117–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nagy KK, Roberts RR, Joseph KT, Smith RF, An GC, Bokhari F, et al. Experience with over 2500 diagnostic peritoneal lavages. Injury. 2000;31:479–82. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(00)00010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scalea TM, Rodriguez A, Chiu WC, Brenneman FD, Fallon WF, Jr, Kato K, et al. Focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST): Results from an international consensus conference. J Trauma. 1999;46:444–72. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199903000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maxwell-Armstrong C, Brooks A, Field M, Hammond J, Abercrombie J. Diagnostic peritoneal lavage. Should trauma guidelines be revised? Emerg Med J. 2002;19:524–5. doi: 10.1136/emj.19.6.524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chiu WC, Cushing BM, Rodriguez A, Ho SM, Mirvis SE, Shanmuganathan K, et al. Abdominal injuries without haemo-peritoneum: A potential limitation of focused abdominal sonography for trauma. J Trauma. 1997;42:617–25. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199704000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ballard RB, Rozycki GS, Newman PG, Cubillos JE, Salomone JP, Ingram WL, et al. An algorithm to reduce the incidence of false-negative FAST examinations in patients at high risk for occult injury. Focused assessment for the sonographic examination of the trauma patient. J Am Coll Surg. 1999;189:145–51. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(99)00121-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Udobi KF, Rodriguez A, Chiu WC, Scalea TM. Role of ultrasonography in penetrating abdominal trauma: A prospective clinical study. J Trauma. 2001;50:475–9. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200103000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boulanger BR, Brenneman FD, McLellan BA, Rizoli SB, Culhane J, Hamilton P. A prospective study of emergent abdominal sonography after blunt abdominal trauma. J Trauma. 1995;39:325–30. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199508000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gupta A, Peckler B, Stone MB, Secko M, Murmu LR, Aggarwal P, et al. Evaluating emergency ultrasound training in India. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2010;3:115–7. doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.62104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brenchley J, Walker A, Sloan JP, Hassan TB, Venables H. Evaluation of focussed assessment with sonography in trauma (FAST) by UK emergency physicians. Emerg Med J. 2006;23:446–8. doi: 10.1136/emj.2005.026864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]