Abstract

Spontaneous esophageal perforation (Boerhaave syndrome) is a very uncommon, life-threatening surgical emergency that should be suspected in all patients presenting with lower thoracic-epigastric pain and a combination of gastrointestinal and respiratory symptoms. Variable clinical manifestations and subtle or unspecific radiographic findings often result in critical diagnostic delays. Multidetector computed tomography complemented with CT-esophagography represents the ideal “one-stop shop” investigation technique to allow a rapid, comprehensive diagnosis of BS, including identification of suggestive periesophageal abnormalities, direct visualization of esophageal perforation and quantification of mediastinitis.

Keywords: Computed tomography, contrast medium, esophagography, esophageal perforation, esophagus

INTRODUCTION

Initially described by Dutch anatomist and physician Herman Boerhaave in 1724 during post-mortem examination performed on Baron Jan Gerrit van Wassenaer, Grand Admiral of the Dutch Fleet, spontaneous esophageal perforation or Boerhaave syndrome (BS) is a very rare surgical emergency, most usually diagnosed in men aged 50-70 years after heavy meal ingestion combined with abundant alcohol consumption. At our tertiary care Hospital, this patient is the only occurrence during the last ten years.[1–3]

Typically, a vertical full-thickness rupture occurs on the left posterior aspect of the distal esophagus, 2-3 cm proximally to the gastroesophageal junction. The pathogenesis involves sudden pressure increase caused by forceful vomiting against a closed glottis because of incomplete cricopharyngeal relaxation. Untreated cases may rapidly progress to infectious mediastinitis and septic shock within 24-48 hours.[1,2,4]

CASE DESCRIPTION

A 69-year-old male with history of chronic gastro-duodenitis and colonic diverticulosis was admitted to Emergency Department because of postprandial epigastric pain radiating to his left hemiabdomen, associated with vomiting. At physical examination, he was found dyspneic and tachypneic, and severe pain was exacerbated during palpation on the upper abdomen without signs of peritonism. Nasogastric tube positioning yielded enteric, partly coffee ground-like fluid.

Technically limited plain radiographs of the thorax and abdomen, obtained with the patient supine, reported predominantly left-sided basal lung opacities consistent with pneumonia and probable associated effusion. Shortly afterwards, because of worsening clinical condition and haemodynamic parameters, urgent contrast-enhanced multidetector CT was requested to rule out acute abnormalities of the thoraco-abdominal aorta.

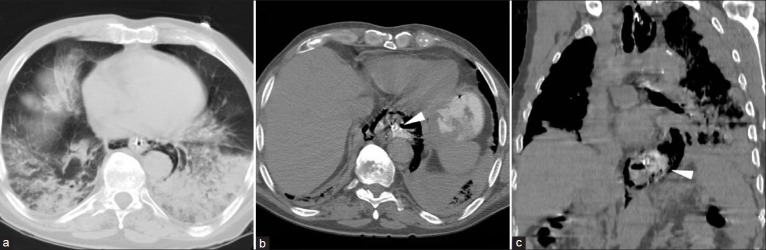

Initial CT acquisition [Figure 1a] disclosed an abnormal posterior mediastinal air collection surrounding the collapsed distal esophagus, suggesting the clinically unsuspected presence of a perforation. Bilateral basal lung infiltrates, with extensive involvement of the left inferior lobe, were attributed to aspiration pneumonia. With the patient still on the CT scanner table, further investigation with CT-esophagography was performed with administration of diluted iodinated contrast medium through the nasogastric tube [Figure 1b and c]. Evidence of extraluminal contrast leakage confirmed the presence of a focal wall disruption on the left postero-lateral aspect of the distal esophagus. Both the esophageal perforation and the associated mediastinal contamination were depicted along three planes by means of multiplanar CT reformations. Contrast-enhanced CT acquisition excluded acute aortic diseases.

Figure 1.

On an axial image from initial CT acquisition (a) viewed at lung window settings) an abnormal air collection is detected in the posterior mediastinum, surrounding the collapsed distal esophagus with nasogastric tube. Basal lung infiltrates, with extensive involvement of the left inferior lobe, are consistent with aspiration pneumonia. Further investigation with CT esophagography (axial image in (b) coronal reformation in (c) visualize increasing posterior pneumomediastinum and extraluminal water-soluble contrast leakage (arrowheads) indicating full-thickness esophageal perforation

Antibiotic treatment with intravenous piperacilline was started. Urgent surgery was performed, including thoracotomic access, posterior mediastinal debridement and irrigation. In agreement with CT findings, after a full-thickness distal esophageal perforation was identified and primarily repaired, without the need for resection. Drainage tube was left in place postoperatively. Supportive therapy and parenteral nutrition therapy were protracted during 32 days of Intensive Care Unit stay. Antibiotics were modified with introduction of cefazoline, according to pus cultures and antibiogram. The patient finally recovered and was discharged from the hospital nearly two months after initial admission.

DISCUSSION

The first aim of this paper is to remind clinicians of this uncommon disease, that should be promptly diagnosed and correctly treated in order to prevent its most severe consequences: despite diagnostic, surgical and critical care advancements, esophageal perforation remains a life-threatening condition associated with high morbidity and mortality (18-50%).[1,4,5] According to the literature, due to its rarity, unspecific clinical presentation and subtle or absent findings on plain radiographs, BS usually represents a diagnostic challenge. The cardinal symptom is sudden lower thoracic pain, sometimes radiating to the back and aggravated by swallowing, associated with vomiting and variable signs of systemic inflammatory response, respiratory and hemodynamic compromission.[2,4]

Unless specifically considered in the differential diagnosis, spontaneous esophageal perforation is often unsuspected or misdiagnosed, since its manifestations closely mimic other more common intrathoracic diseases, including myocardial infarction and pericarditis, acute aortic disease or even abdominal emergencies such as perforated peptic ulcer or acute pancreatitis. Unfortunately, diagnostic work-up delays may hinder timely treatment with a negative effect on patients’ outcome.[1,2,4,5]

Although controversy exists about appropriate therapy, surgical management is currently considered the gold standard for ruptures diagnosed within 24 hours from onset and allows a 75% chance of recovery. Surgery should include pleural cavity drainage, perforation debridement and primary repair through an open thoracotomic or laparoscopic approach. Conservative management with resuscitation and broad-spectrum antibiotics should be reserved for patients with minimal sepsis and mediastinal abnormalities, and for those too unstable to undergo surgery. After 24 hours, survival rates as low as 20% have been reported, therefore a high index of clinical suspicion and prompt diagnostic assessment are needed.[1,2,4,5]

In emergency departments, plain films of the thorax and abdomen are usually performed as the initial imaging procedure to investigate abdominal pain and vomiting. Unfortunately, in severely ill, uncooperative patients who cannot stand up and hold their breath plain radiographs often result technically inadequate with a limited diagnostic value. The usual although unspecific radiographic features of BS include predominantly left-sided pleural effusion, lung infiltrates and atelectasis, whereas more specific signs such as pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum and pneumopericardium are rarely detected or very subtle.[3,4,6,7]

In the past, fluoroscopic esophagography with ingestion of water-soluble contrast medium was used to confirm suspected esophageal perforation through the direct demonstration of extraluminal contrast extravasation. Cumbersome to perform in severely ill, bed-ridden patients, this technique is associated with a significant rate (10-38%) of false-negative results and with the potential risk of pulmonary oedema precipitated by aspiration of orally administered contrast.[4–6,8]

The second objective of this report is to present the useful role of multidetector CT-esophagography, a relatively new “one-stop-shop” technique that provides fast, comprehensive diagnosis of BS.[8] Currently, the vast majority of patients with acute chest and/or abdominal symptoms undergo multidetector CT as the initial emergency investigation. As this case exemplifies, mediastinal findings suggestive of esophageal injury and associated mediastinitis (such as periesophageal and mediastinal gas and/or mediastinal fluid collections, esophageal wall thickening, pleural effusion or hydrothorax) are reliably identified on thoraco-abdominal emergency CT examinations performed under alternative clinical diagnoses.[3,6–8]

Clinical or CT features suggesting the diagnosis of BS should be further investigated by means of CT-esophagography with oral ingestion or administration through the nasogastric tube of 10% diluted iodinated contrast medium, and reconstruction of multiplanar images. Easily performed as a complement of initial CT acquisition, CT-esophagography allows to confirm and visually document the perforation through the direct identification of extraluminal contrast leakage. The time spared without transferring the patient from the CT scanner table to the fluoroscopic suite may prove prognostically important.[3,4,6,8]

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Teh E, Edwards J, Duffy J, Beggs D. Boerhaave's syndrome: A review of management and outcome. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2007;6:640–3. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2007.151936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khan AZ, Strauss D, Mason RC. Boerhaave's syndrome: Diagnosis and surgical management. Surgeon. 2007;5:39–44. doi: 10.1016/s1479-666x(07)80110-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghanem N, Altehoefer C, Springer O, Furtwängler A, Kotter E, Schäfer O, et al. Radiological findings in Boerhaave's syndrome. Emerg Radiol. 2003;10:8–13. doi: 10.1007/s10140-002-0264-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Søreide JA, Viste A. Esophageal perforation: Diagnostic work-up and clinical decision-making in the first 24 hours. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2011;19:66. doi: 10.1186/1757-7241-19-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaker H, Elsayed H, Whittle I, Hussein S, Shackcloth M. The influence of the ‘golden 24-h rule’ on the prognosis of oesophageal perforation in the modern era. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010;38:216–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2010.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giménez A, Franquet T, Erasmus JJ, Martínez S, Estrada P. Thoracic complications of esophageal disorders. Radiographics. 2002;22:S247–58. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.22.suppl_1.g02oc18s247. Spec No. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Young CA, Menias CO, Bhalla S, Prasad SR. CT features of esophageal emergencies. Radiographics. 2008;28:1541–53. doi: 10.1148/rg.286085520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fadoo F, Ruiz DE, Dawn SK, Webb WR, Gotway MB. Helical CT esophagography for the evaluation of suspected esophageal perforation or rupture. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182:1177–9. doi: 10.2214/ajr.182.5.1821177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]