Abstract

Objective: The aim of this randomized longitudinal clinical study was to assess different treatment protocols for dentin hypersensitivity with high-power laser, desensitizing agent, and its association between high-power laser and desensitizing agent, for a period of 6 months. Background data: The literature shows a lack of treatment for dentin hypersensitivity, and lasers are contemporary alternatives. Methods: After inclusion and exclusion analysis, volunteers were selected. The lesions were divided into three groups (n=10): G1, Gluma Desensitizer (Heraeus Kulzer); G2, Nd:YAG Laser (Power Laser™ ST6, Lares Research®) contact mode, laser protocol of 1.5 W, 10 Hz, and 100 mJ,≈85 J/cm2, four irradiations performed, each for 15 sec, in mesiodistal and occluso-apical directions, totaling 60 sec of irradiation with intervals of 10 sec between them; G3, Nd:YAG Laser+Gluma Desensitizer. The level of sensitivity to pain of each volunteer was analyzed by visual analog scale (VAS) using cold air stimuli and exploratory probe 5 min, 1 week, and 1, 3, and 6 months after treatment. Data were collected and subjected to statistical analysis that detected statistically significant differences between the various studied time intervals of treatments (p>0.05). Results: For the air stimulus, no significant differences were found for each time interval. For the long-term evaluation, all groups showed statistical differences (p>0.05), indicating that for G2 and G3, this difference was statistically significant from the first time of evaluation (post 1), whereas in G1, the difference was significant from the post 2 evaluation (1 week). Comparison among groups using the probe stimulation showed significant differences in pain (p<0.001). Only in G1 and G3 did this difference become significant from post 01. Conclusions: All protocols were effective in reducing dentinal hypersensitivity after 6 months of treatment; however, the association of Nd:YAG and Gluma Desensitizer is an effective treatment strategy that has immediate and long-lasting effects.

Introduction

Modern concepts in dentistry have led to a reduction in tooth loss from caries lesions. On the other hand, the longer life of teeth in the oral cavity has brought an increase in the occurrence of noncarious cervical lesions, namely erosion, abrasion, abfraction, and attrition.1,2 As a consequence, dentin hypersensitivity has been shown to be a common complaint among adults, and represents one of the most critical and painful conditions in dentistry.3,4

The increased frequency of dentin hypersensitivity has been reported in cases of teeth with gingival recession, poor oral hygiene, parafunctional habits, aggressive tooth brushing, erosion resulting from food factors, bad positioning of teeth, chronic periodontal diseases, periodontal surgery, occlusal problems, age, or a combination of these factors.5

The essential feature for the presence of dentin hypersensitivity is the exposure of dentin surfaces with open dentinal tubules, and the most accepted theory to explain the pain related to dentin hypersensitivity is the hydrodynamic theory.6 According to the theory, when dentinal tubules in vital teeth are exposed, fluid within the dentinal tubules may flow in either an inward or outward direction, depending upon pressure differences in the surrounding tissue. These intratubular fluid shifts can activate mechanoreceptors in intratubular nerves or in the superficial pulp, and are perceived by the patient as a pain with a rapid onset, sharp in character and duration.7 Therefore, it is reasonable to provide a treatment for dentin hypersensitivity that would seal dentinal tubules and would not allow the movement of fluid flow.

Different treatment modalities have been described, such as occlusal adjustment, dietary advice, brushing instructions, application of adhesive systems, adhesive restorations, application of desensitizing products/salts (potassium ions, oxalate, sodium fluoride) and irradiation with low- and high-power lasers.5,8,9 The latter treatment has been demonstrated to be efficient in reducing dentin hypersensitivity and can be described as a method of treatment for dentin hypersensitivity. As there is no consensus about the most satisfactory technique or product that would ensure a long-lasting effect, the use of lasers has been presented as an alternative treatment, providing partial or complete obliteration of dentinal tubules, with satisfactory results described in the literature.

High-power lasers such as carbon dioxide (CO2), neodymium: yttrium-aluminum-garnet (Nd:YAG) erbium, yttrium-aluminum-garnet: (Er:YAG) and erbium chromium: yttrium – scandium – gallium-garnet (Er,Cr:YSGG), and surgical diode lasers, are examples of the types of equipment used in dentistry.10–18 Among them, the mode of action of Nd:YAG laser is highlighted. This equipment has been used since 1985 and has shown the ability to obliterate the tubules through a process called “melting and re-solidification,” without causing pulp damage or cracks when used with an appropriate protocol.19,20 In addition, Nd:YAG laser was shown to be capable of producing a sealing depth of ∼4 μm within the tubules, usually causing an immediate reduction in dentin hypersensitivity.20

Therefore, the objective of this in vivo study was to assess different treatment protocols for dentin hypersensitivity treatment with a desensitizing agent, high-power laser, and their association between high-power laser and desensitizing agent for a period of 6 months.

Materials and Methods

The research protocol was initially submitted to the Ethics Committee of the local institution (Protocol 62/07). Patients who gave their oral and voluntary written informed consent, and were aware of the study inclusion and exclusion criteria, were examined before participating in the study. A detailed medical and dental history was recorded.

Patients were considered suitable for the study if they had sensitive teeth showing tooth wear or gingival recession with exposure of cervical dentin. Patients with teeth showing evidence of irreversible pulpitis or necrosis, carious lesions, defective restorations, facets of attrition, premature contact, cracked enamel, active periodontal disease, use of daily doses of medications, or any factor that could be responsible for sensitivity, were also excluded. Also excluded were patients who had undergone professional desensitizing therapy during the previous 3 months; and women who were pregnant or breast-feeding. Differential diagnosis was performed and the vitality of all teeth was verified.

After clinical examination, 24 patients were selected, and 33 teeth (n=11) received treatment. All lesions were located on the facial surface of the teeth. If the patient had two or more lesions side by side in the same quadrant, only one of the lesions would receive the treatment, at that time.

During the first screening visit, dietary counseling and oral hygiene instructions, and techniques with non-fluoride toothpaste were also provided. After that, all patients were standardized and the lesions were randomly assigned to the groups.

The degree of dentin hypersensitivity was determined by a visual analog scale (VAS). All patients were asked to define their level of dentin hypersensitivity using the VAS on a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 represented “no pain” and 10 “the worst pain.” Each patient was asked to rate the perception of discomfort after the application of air using a dental syringe for 3 sec, 2 mm away from and perpendicular to the root surface. The adjacent teeth were isolated with cotton rolls to prevent false positive results. In addition, a dental probe was used to scratch the surface in a mesial to distal direction. VAS scale was also used to determine the level of pain. All stimuli were given by one operator (Operator 1), with the patient seated in the same dental chair, with the same equipment yielding similar air pressure and probe pressure. This first measurement was considered the baseline (pre 01). The level of sensitivity was measured by VAS scale at time intervals of 5 min (post 1), 1 week (post 2), and 1 (post 3), 3 (post 4), and 6 (post 5) months after the treatments, by Operator 2.

After the first measurement, the cervical lesions and recessions were randomly divided into the three experimental groups using a Microsoft Office Excel program. No negative control group (placebo group) was allowed by the Ethics Committee.

Desensitizer agent (Gluma Desensitizer)

A few drops of Gluma Desensitizer (Heraeus Kulzer, Armonk, NY) were applied with a cotton pellet using a gentle but firm rubbing motion. After 30–60 sec, the area was dried thoroughly until the fluid disappeared and the surface was not shiny.

Nd:YAG laser irradiation

The irradiation with Nd:YAG laser (Power Laser™ ST6, Lares Research®, San Clemente, CA- FAPESP 07/55487-0) was performed in pulsed form, contact mode, perpendicular to the surface, and with power of 1.5 W, repetition rate of 10 Hz, and 100 mJ of energy. A 400 μm quartz fiber was used, with pre-established movements in the occluso-apical and mesiodistal directions and vice versa. Therefore, the energy density calculated was≈83.3 J/cm2. Four irradiations of 15 sec each were performed, totaling 60 sec of irradiation. An interval of 10 sec between the irradiations was necessary for thermal relaxation of the tissue.

For G3, in which the association of Nd:YAG laser irradiation and application of desensitizing agent Gluma Desensitizer was used, the irradiation protocol was initially performed, and then the product was applied according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical analysis

Data for statistical analysis were collected using the Minitab Statistical software, version 16.1. All analyses were conducted separately for the air stimulus and probe, and each tooth was assessed individually. The level of significance was considered for values of p<0.05. Initially, the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to verify the distribution of data. As it did not present a normal distribution, the nonparametrical Kruskal–Wallis and Friedman tests were performed for the comparison between the experimental groups and studied time intervals, respectively.

Results

Comparison among groups showed no significant difference in pain levels in the pre-treatment period (p=0.097). For each time interval, no significant differences were found among treatments.

For the long-term evaluation, each group was analyzed individually. All of them showed statistical differences (p>0.05), indicating that for groups Nd:YAG laser and Nd:YAG laser associated with Gluma Desensitizer, this difference was statistically significant from the first time of evaluation (post 1), whereas in the other groups, the difference was significant from the post 2 evaluation (1 week after treatment). Figure 1 shows the graphics in which the reduction of pain levels with air stimulus for all treatments can be observed.

FIG. 1.

Representative graphics for median of pain level and standard deviations, according to the treatment used and the period of evaluation for air stimulus.

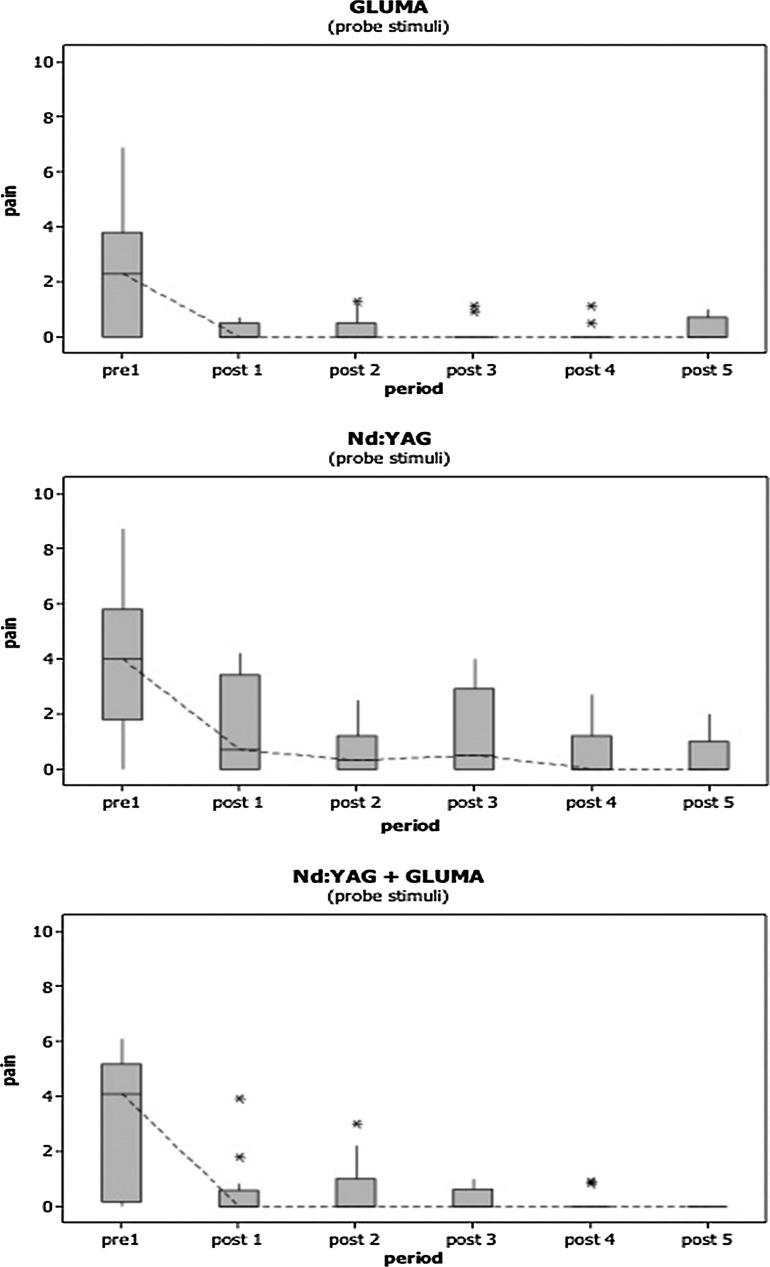

For the probe stimulus, once again, data did not show normal distribution and were therefore analyzed using nonparametric tests. Figure 2 shows the graphics for pain (median) reduction obtained according to the treatment used and the assessment period. Similarly to the results achieved with the air stimulus, comparison among groups using the probe stimulation showed no significant difference in pain during pre-treatment (p=0.321); therefore, it was not necessary to transform the data to compare over time.

FIG. 2.

Representative graphics for median of pain level and standard deviations, according to the treatment used and the period of evaluation for probe stimulus.

To evaluate pain over time, each group was analyzed separately. All showed significant differences in pain (p<0.001). The multiple comparison test showed that only in the Gluma and Nd:YAG+Gluma groups did this difference became significant from post 01. Group Nd:YAG showed a significant difference from the post 02/second evaluation time interval.

No complications, such as allergic reactions or pulpal injuries, were observed during the period of study. All teeth remained vital after the treatments, with no adverse reaction or clinical complications reported.

Discussion

Dentin hypersensitivity is the most frequent complaint reported by patients, and the individual need for treatment depends on the etiology; degree of discomfort related; extension and depth of the lesion, which may affect mastication; ingestion of liquids; respiration; and ability to maintain plaque control, and sometimes may lead to emotional changes that may alter the patient's lifestyle.

In the present study, some of the patients reported a pain so severe that this pathology became a physical and emotional problem. Many were unable to ingest hot or cold foods or liquids, sweets, acid foods, or drinks and even had difficulty with brushing their teeth because of the pain reported.

The professional approach to the treatment of dentin hypersensitivity has always been based on the results of treatments performed, irrespective of the approach to etiologic and existent predisposing factors.21 This manner of approach created a problem in the resolution of a clinical protocol for the treatment of dentin hypersensitivity. At present, there are a large number of products available to professionals; however, many have been shown to be misleading as regards their efficacy.21 A review of clinical trials in dentin hypersensitivity helps to explain this fallacy. Generally, the protocols that compare the different agents are not standardized, resulting in innumerable variables that often cannot be compared. The treatments rarely take into account etiologic factors, and it is difficult to quantify the pain related, because of its subjective nature. Many studies have used VAS of pain; others have used questionnaires to evaluate the patient. In addition, factors such as the placebo effect, Hawthorne effect, regression for the effect of the control product, differences in methodologies, duration of studies, and studied population, prevent comparison of the results and affirmation of a standard treatment protocol.22

As has been described, in order to have dentin hypersensitivity, there must be exposure of the dentinal tubules.22 Studies analyzing scanning electron microscopies have shown that the number of open tubules per unit of area is eight times higher, in addition to their diameter being twice as wide in sensitive dentin.23,24 Therefore, the concept of treatment for dentin hypersensitivity consists of a barrier that completely or partially obliterates the dentinal tubules, preventing the movement of fluid, and this is a logical conclusion for treatment, based on the hydrodynamic theory postulated by Brännström and Astrom.6

It is interesting to note that Grossman, in 1935, suggested several ideal characteristics for a desensitizing agent.25 These characteristics, which would be essential for the treatment of dentin hypersensitivity, could be valid up to today. The material would need to be easy to apply, be painless, act rapidly, not be a pulp irritant, not cause alterations in the tooth structure, and have a long-lasting effect. In the present study, none of the treatments presented undesirable or secondary effects, which confirms that if adequately used, they are safe and easily reproducible treatments.

Gluma Desensitizer is an example, as can be seen in this study, of a product that has shown promising results in clinical research.26–28 This desensitizing agent contains hydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEMA), benzalkonium chloride, glutaraldehyde, and fluoride in its formula. Glutaraldehyde causes coagulation of proteins inside the dentinal tubules, reacting with the albumin in dentinal fluid, thus causing the precipitation of albumin. As a result of this reaction, HEMA polymerization occurs, which is able to form deep tags, so that there is partial or complete obliteration of the dentinal tubules and consequent reduction in dentin hypersensitivity.27 The tags that cause occlusion of the dentinal tubules may reach a depth of 200 μm.29

In the present study, the group treated with Gluma Desensitizer showed clinical results that were expected, probably with complete obliteration of dentinal tubules, thereby significantly reducing pain levels, both for air and probe stimulation, as well as immediately and over the course of time.

The need for an alternative treatment, preferably one showing long-term efficiency, appeared in view of innumerable responses to the available desensitizing agents. With the discovery and development of laser technology, right from the discovery of the first ruby laser, a new treatment option for dentin hypersensitivity appeared and a variety of lasers have been developed and tested. The Nd:YAG laser was the first described in the literature; however, other wavelengths can be used such as the CO2 (10600 nm), associated with a calcium hydroxiapatite paste, Er:YAG (2940 nm) and Er,Cr:YSGG (2780 nm).

High power laser which is outstanding in the literature and clinic, in cases of treatment for the reduction of pain in dentin hypersensitivity, is Nd:YAG laser.13,15,30–36 The fact that this equipment performs the dissolution and re-solidification of the hydroxyapatite crystals in dentin, forming a differentiated layer with a sealing depth of ∼4 μm within the dentinal tubules, should result in the elimination of dentin hypersensitivity for a prolonged period of time. Studies in the literature, which compare the use of Nd:YAG laser with other types of equipment or desensitizing agents, have shown its superiority. Dilsiz et al. (2010)13 evaluated the effectiveness of Er:YAG, Er,Cr:YSGG and a low-level diode laser as dentin desensitizers and concluded that all of them can be used to reduce dentin hypersensitivity. However, the results of the Nd:YAG laser irradiation were more effective and it seems to be a suitable tool for successful reduction of dentin hypersensitivity. Comparisons between the Nd:YAG and Er:YAG lasers have also shown the superiority of Nd:YAG laser in reducing patients' pain and occluding tubules.15,34,37

The results in the literature are in agreement with the results of the present study. Nd:YAG laser presented immediate and long-term results without adverse effects.36

In addition, according to the literature, only Nd:YAG laser appears to have an additional analgesic effect when compared with the other high power lasers. This most probably occurs because the irradiation may temporarily alter the final part of the sensory axons and block both the C and Aβ fibers, thereby diminishing pain.38 This mechanism should explain why a significant decrease at the second evaluation period (post 2) was observed compared with post 1.

In spite of melting occurring after irradiation with Nd:YAG laser, one cannot be clinically certain that there was occlusion of all the dentinal tubules with the protocol applied in this study, but one also cannot increase the power provided by the equipment. Zapletalová et al.39 showed that powers >1.5 W may cause microcracks or even carbonization of the tooth surface, and consequent increase in intra-pulp temperature, causing irreversible injuries. The guarantee of not sealing of all the dentinal tubules may explain why some patients, even after irradiation with Nd:YAG laser, still had pain.

The present study showed that the only group in which all the sample presented no pain at the end of evaluation was the group in which Nd:YAG laser was associated with the Gluma Desensitizing agent. Therefore, if any tubules were not sealed by means of the re-solidification process by Nd:YAG laser, this could be complemented by the desensitizing agent, as a way to reduce the number of open dentin tubules to the maximum extent. Farmakis et al. showed a combined approach of treatment that showed potential to improve the outcome of treatment for dentin hypersensitivity.40 The authors used a bioglass combined with Nd:YAG laser irradiation and suggested this combined treatment, as was used by the authors of the present study.

It is necessary to report that it is difficult to qualify the pain caused by dentin hypersensitivity. The VAS was chosen to measure the pain of the patients in this study, because according to the literature, it is considered adequate for the measurement of pain in studies, as it has the advantage of being a continuous scale, easy for patients to understand, with the capacity to discriminate different types of pain in different studies, such as the pain in dentin hypersensitivity.32,37,41,42

In spite of the great variety of materials and techniques existent, dentin hypersensitivity is still considered a chronic problem in dentistry, because of the difficulty of measuring pain, choice of material, most suitable technique, and the uncertain prognosis.16 It is necessary to consider the severity of the dentinal hypersensitivity before the use of laser, and it is also necessary to use correct and safe protocols. Nevertheless, considering its effectiveness and simplicity, treatment with high-power laser is a conservative and appropriate option for the treatment of dentin hypersensitivity, provided that the correct protocols, based on scientific evidence, are used.

Conclusions

Within the limits of this study, it can be concluded that:

All the current treatments were effective in reducing cervical dentin hypersensitivity.

Statistically, after the reduction of pain, this pain remained stable until the last evaluation. After 6 months of treatment there was no increase in pain.

The association of Nd:YAG and Gluma Desensitizer is an effective treatment strategy that has immediate and long-lasting effects.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Sao Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) for grants #2011/17701-6 and #2010/13232-9 and the Special Laboratory of Lasers for the infrastructure provided.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Bartlett D.W. The role of erosion in tooth wear: aetiology, prevention and management. Int. Dent. J. 2005;55:277–284. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2005.tb00065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartlett D.W. Shah P. A critical review of non-carious cervical (wear) lesions and the role of abfraction, erosion, and abrasion. J. Dent. Res. 2006;85:306–312. doi: 10.1177/154405910608500405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holland G.R. Narhi M.N. Addy M. Gangarosa L. Orchardson R. Guidelines for the design and conduct of clinical trials on dentine hypersensitivity. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1997;24:808–813. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1997.tb01194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Canadian Advisory Board on Dentin Hypersensitivity. Consensus-based recommendations for the diagnosis and management of dentin hypersensitivity. J. Can. Dent. Assoc. 2003;69:221–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Orchardson R. Gillam D.G. Managing dentin hypersensitivity. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2006;137:990–998. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2006.0321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brännström M. Astrom A. The hydrodynamics of the dentine; its possible relationship to dentinal pain. Int. Dent. J. 1972;22:219–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brännström M. Sensitivity of dentine. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1966;21:517–526. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(66)90411-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Markowitz K. Pashley D.H. Discovering new treatments for sensitive teeth: the long path from biology to therapy. J. Oral. Rehabil. 2008;35:300–315. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2007.01798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kimura Y. Wider–Smith P. Yonaga K. Matsumoto K. Treatment of dentine hypersensitivity by lasers: a review. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2000;27:715–721. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2000.027010715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lan W.H. Liu H.C. Sealing oh human dentinal tubules by Nd: YAG laser. J Clin. Laser Med. Surg. 1995;13:329–333. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moritz A. Schoop U. Goharkhay K., et al. Long-term effects of CO2 laser irradiation on treatment of hypersensitive dental necks: results of an in vivo study. J. Clin. Laser Med. Surg. 1998;16:211–215. doi: 10.1089/clm.1998.16.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwarz F. Arweiler N. Georg T. Reich E. Desensitizing effects of an Er:YAG laser on hypersensitivity dentine. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2002;29:211–215. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2002.290305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dilsiz A. Aydn T. Emrem G. Effects of the combined desensitizing dentifrice and diode laser therapy in the treatment of desensitization of teeth with gingival recession. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2010;28:69–74. doi: 10.1089/pho.2009.2640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Romano A.C. Aranha A.C. Lopes da Silveira B. Baldochi S.L. Eduardo C.P. Evaluation of carbon dioxide laser irradiation associated with calcium hydroxide in the treatment of dentineal hypersensitivity. A preliminary study. Lasers Med. Sci. 2011;26:35–42. doi: 10.1007/s10103-009-0746-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gholami G.A. Fekrazad R. Esmaiel–Nejad A. Kalhori K.A. An evaluation of the occluding effects of Er;Cr:YSGG, Nd:YAG, CO2 and diode lasers on dentinal tubules: a scanning electron microscope in vitro study. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2011;29:115–21. doi: 10.1089/pho.2009.2628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yilmaz H.G. Cengiz E. Kurtulmus–Yilmaz S. Leblebicioglu B. Effectiveness of Er,Cr:YSGG laser on dentine hypersensitivity: a controlled clinical trial. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2011;38:341–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2010.01694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aranha A.C. Eduardo, Cde P. Effects of Er:YAG and Er,Cr:YSGG lasers on dentine hypersensitivity. Short-term clinical evaluation. Lasers Med. Sci. 2012 Jul;27:813–818. doi: 10.1007/s10103-011-0988-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aranha A.C. de Paula Eduardo C. In vitro effects of Er,Cr:YSGG laser on dentine hypersensitivity. Dentine permeability and scanning electron microscopy analysis. Lasers Med.Sci. 2012;27:827–834. doi: 10.1007/s10103-011-0986-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsumoto K. Funai H. Shirasuka T. Wakabayashi H. Effects of Nd:YAG laser in treatment of cervical hypersensitive dentine. Jpn. J. Conserv. Dent. 1985;28:760–765. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu H.C. Lin C.P. Lan W.H. Sealing depth of Nd: YAG laser on human dentinal tubules. J. Endod. 1997;23:691–693. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(97)80403-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.West N.X. Dentine hypersensitivity: preventive and therapeutic approaches to treatment. Periodontol. 2008;2000;48:31–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2008.00262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.West N.X. Dentine hypersensitivity. Monogr. Oral. Sci. 2006;20:173–189. doi: 10.1159/000093362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rimondini L. Baroni C. Carassi A. Ultrastructure of hypersensitive and non-sensitive dentin. A study on replica models. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1995;22:899–902. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1995.tb01792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoshiyama A.M., et al. Morphological characterization of tubule-like structures in hypersensitive human radicular dentin. J. Dent. 1996;24:57–63. doi: 10.1016/0300-5712(95)00016-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grossman L.I. A systematic method for the treatment of hypersensitivity dentin. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 1935;22:592–602. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dondi dall'Orologio G. Lorenzi R. Anselmi M. Grisso V. Dentindesensitizing effects of Gluma alternate, Health-Dent Desensitizer and Scotchbond Multi-Purpose. Am. J. Dent. 1999;12:103–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dondi dall'Orologio G. Lone A. Finger W.J. Clinical evaluation of the role of glutardialdehyde in a one-bottle adhesive. Am. J. Dent. 2002;15:330–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aranha A.C.C. Pimenta L.A. Marchi G.M. Clinical evaluation of desensitizing treatments for cervical dentin hypersensitivity. Braz. Oral. Res. 2009;23:333–339. doi: 10.1590/s1806-83242009000300018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schüpbach P. Lutz F. Finger W. Closing of dentinal tubules by Gluma desensitizer. Eur. J. Oral. Sci. 1997;105:414–421. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1997.tb02138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gelskey S.C. White J.M. Pruthi V.K. The effectiveness of the Nd:YAG laser in the treatment of dental hypersensitivity. J. Can. Dent. Assoc. 1993;59:377–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gutknecht N. Moritz A. Dercks H.W. Lampert F. Treatment of hypersensitive teeth using neodymium; yttrium-aluminum-garnet lasers; a comparison of the use of various settings in an in vivo study. J. Clin. Laser. Med. Surg. 1997;15:171–174. doi: 10.1089/clm.1997.15.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lier B.B. Rosing C.K. Aass A.M. Gjermo P. Treatment of dentin hypersensitivity by Nd:YAG laser. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2002;29:501–506. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2002.290605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ciaramicoli M.T. Carvalho R.C.R. Eduardo C.P. Treatment of cervical dentin hypersensitivity using neodymium:yttrim-aluminum-garnet laser. Clinical evaluation. Lasers Surg. Med. 2003;33:358–362. doi: 10.1002/lsm.10232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aranha A.C. Domingues F.B. Franco V.O. Gutknecht N. Eduardo C.P. Effect of Er:YAG and Nd:YAG lasers on dentin permeability in root surfaces: a preliminary in vitro study. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2005;23:504–508. doi: 10.1089/pho.2005.23.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Naylor F. Aranha A.C. Eduardo C.P. Arana–Chavez V.E. Sobral M.A. Micromorphological analysis of dentinal structure after irradiation with Nd:YAG laser and immersion in acidic beverages. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2006;24:745–752. doi: 10.1089/pho.2006.24.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kara C. Orbak R. Comparative evaluation of Nd:YAG laser and fluoride varnish for the treatment of dentinal hypersensitivity. J. Endod. 2009;35:971–974. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Birang R. Poursamimi J. Gutknecht N. Lampert F. Mir M. Comparative evaluation of the effects of Nd:YAG and Er:YAG laser in dentin hypersensitivity treatment. Lasers Med. Sci. 2007;22:21–24. doi: 10.1007/s10103-006-0412-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Myers T.D. McDaniel J.D. The pulsed Nd:YAG dental laser: review of clinical applications. J. Calif. Dent. Assoc. 1991;19:25–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zapletalová Z. Peřina J. Novotvý R. Chmeličková H. Suitable conditions for sealing of open dentinal tubules using a pulsed Nd:YAG laser. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2007;25:495–499. doi: 10.1089/pho.2007.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Farmakis E.T. Kozyrakis K. Khabbaz M.G. Schoop U. Beer F. Moritz A. An vitro evaluation of dentin tubule occlusion by denshield and neodymium-doped yttrium-aluminum-garnet laser irradiation. J. Endod. 2012;38:662–666. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2012.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ide M. Wilson R.F. Ashley F.P. The reproducibility of methods of assessment for cervical dentine hypersensitivity. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2001;28:16–22. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2001.280103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Merika K. Hefti A.F. Preshaw P.M. Comparison of two topical treatments for dentine sensitivity. Eur. J. Prosthodont. Restor. Dent. 2006;14:38–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]