Abstract

Faces are found generally to be perceived as thinner when viewed upside down. When a face is viewed upright, the internal features are thought to influence the perception of face shape. However, when inverted, it has been proposed that disruption to holistic processing means that these factors can no longer be used to judge the shape of a face. We show that it is not the case that an inverted face reverts to some average shape whereby fat faces appear thinner upside down whereas thin faces appear fatter. The fact that the illusion appears to occur for most face shapes is discussed with regard to the horizontal–vertical illusion.

Keywords: face perception, inversion, size, shape

1. Introduction

The ability to recognise thousands of faces across many viewpoint changes, lighting changes, and time scales is, compared with other categories of objects, unique. Considering that faces represent a highly homogeneous class of stimuli, all having the same configuration of two eyes above a nose above a mouth, it has been suggested that discriminating between faces relies on the capacity to combine information about the individual features within a face (featural processing) along with information about the spacing between these features (holistic processing; Tanaka & Farah, 1993).

Despite this expertise at recognising and discriminating faces, the accuracy with which faces are recognised is drastically reduced when the face is inverted. One of the first experiments to document this phenomenon was conducted by Yin (1969), in which memory for faces, along with other objects usually only seen in a canonical upright orientation, was compared. It was found that, whilst memory for all objects was impaired when inverted, memory for faces was affected to a much greater degree. Findings such as these have resulted in the idea that faces represent a “special” class of stimuli.

It is generally accepted that inverting a face results in some of the strategies used in processing upright faces becoming ineffective. Many researchers have proposed that face inversion affects the ability to use configural processing whilst leaving the ability to use featural processing intact (Carey & Diamond, 1977; Farah, Tanaka, & Drain, 1995; Leder & Bruce, 2000; Maurer, Le Grand, & Mondloch, 2002). As a result of this, any changes to the configuration of the internal features of a face should be apparent when viewed upright, but disappear once the face is inverted. When the eyes and the mouth of a face are inverted within an upright face, the resulting “thatcherised” image is perceived as grotesque (Thompson, 1980). However, when this “thatcherised” image is inverted, the grotesqueness disappears and the face is perceived as normal. Bartlett and Searcy (1993) state that this effect is due to the fact that “thatcherising” a face affects the holistic information derived from a face whilst leaving the featural information intact. Because the processing of inverted faces relies on featural information, the changes are not apparent.

The loss of the ability to use holistic processing is further demonstrated in an experiment by Searcy and Bartlett (1996). Participants were required to rate the grotesqueness of a face when upright or inverted. Faces presented could have spatial distortions, whereby the spacing between the eyes, nose, and mouth was adjusted, or component distortions achieved by a blurring of the pupils or a blackening of the teeth. When inverted, grotesqueness ratings for the spatially distorted faces were significantly lower than for component-distorted faces, suggesting that face inversion affects the encoding of holistic information much more than information derived from the features of the face. These findings were replicated by Murray, Yong, and Rhodes (2000).

These investigations confirmed that a change to the internal spacing of the features of the face is apparent only when viewed in an upright orientation. Kemp, McManus, and Pigott (1990) made direct measurements of discrimination of eye position in upright, inverted, and photographic negative face images and found that sensitivity to spatial shifts of eyes both vertically and horizontally was reduced in inverted and negative faces. A further demonstration of this lack of sensitivity to the configural cues in inverted faces is that devised by Helmut Leder, who stretched the nose of the actor Paul Newman such that the distortion was readily apparent in an upright face but largely overlooked in the inverted version; see Figure 5.1a in Bruce and Young (1998, p. 152).

The spacing of the internal features has further been reported to affect the way external objects are perceived. Lee and Freire (1999) demonstrated that when an oval aperture was placed over a face, removing all the external features, the oval appears more elongated when the distance between the internal facial features is increased. However, when the distance between the internal facial features is decreased, creating the illusion of a shorter looking face, the oval appears rounder. The authors noted that inversion reduces this effect. Because inversion renders the ability to process the holistic information of a face ineffective, the reduction in the effect could be attributed to an inability to use the information about the spatial relationships between features.

However, Schwaninger, Ryf, and Hofer (2003) suggest that whilst the poor performance of recognition of inverted faces can be attributed to a loss of configural processing, the actual perception of configural information is unaffected by inversion. It was found that when asked to estimate the distance between the internal features of a face, participants overestimated the distance between the eyes and mouth by 39% and the distance between the two eyes by 11%. The latter result, the estimate of inter-pupillary distance, may seem small compared with the figure of around 30% found by Thompson (2002). However, in that study participants were required to estimate their own inter-pupillary distance from memory. The overestimations found by Schwaninger et al. were maintained when the face was inverted. The question whether the reduction in the illusion found with inverted faces (reported by Lee & Freire, 1999) can be attributed to a disruption in holistic processing.

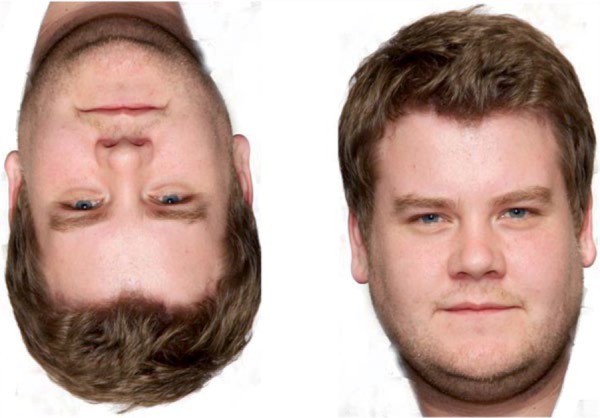

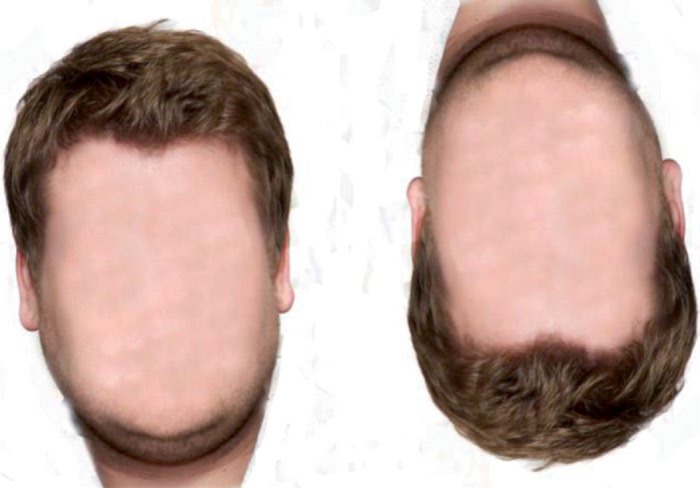

During a classroom demonstration to illustrate the reduced recognition of inverted familiar faces, it was observed that the face of James Corden, a British TV and stage actor, appeared noticeably thinner when presented upside down (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A face that appears dramatically thinner when inverted. This is not the picture used when the effect was first observed. James Corden holds the copyright of that picture and he has indicated that he does not want to be involved in this study.

The aim of this investigation was to quantify this illusion and to explore why inversion should bring about a perceived change in size of the face. It may well be that configural cues lose their influence in inverted faces, but that alone is not an explanation of the illusion.

2. Experiment 1

Experiment 1 aimed to quantify the basic observation that an inverted face appears thinner than its upright counterpart. It was hypothesised that the inverted face would appear significantly thinner than the matching upright face.

Forced-choice methods were used in both Experiments 1 and 2. Participants were presented with two faces with either an upright–upright (UU), inverted–inverted (II), or upright–inverted (UI) configuration and were required to press a key to indicate which face appeared to be “fatter.” The use of the word “fatter” was to emphasise to the participants that they were to make a judgement of face shape rather than one of size (e.g. “bigger”) or linear extent (e.g. “wider”). The data were used to construct psychometric functions, from which points of subjective equality (PSEs) were calculated.

2.1. Method

2.1.1. Participants

Fourteen participants took part in the experiment. The participants ranged in age from 19 to 29, with a mean age of 21.7 years.

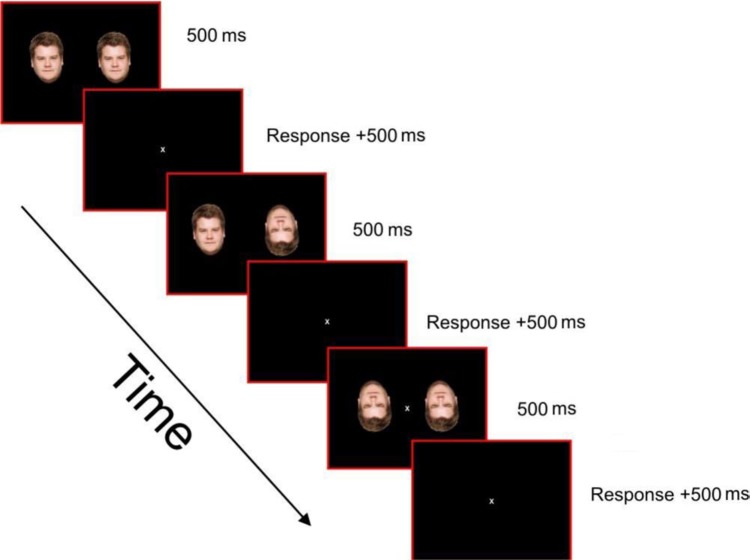

2.1.2. Design and procedure

Pairs of faces, a “standard face” with a “match” face, were presented on a computer screen 50 cm from the participant. Participants indicated which of the two faces looked “fatter.” The standard face was 78 mm (8.9 deg of visual angle) in width with the nine match faces having widths ranging from a difference of −8 mm through to +8 mm in 2-mm intervals (steps of approximately 0.23 deg of arc each). The transformed faces were simply expanded in the horizontal direction, keeping the vertical dimensions unchanged. The two faces were presented for 500 ms on a black background, separated by a horizontal distance of 14 deg, which placed the centre of each face 7 deg from fixation. The faces in each presentation could both be upright (UU), both inverted (II), or with the standard upright and the match face inverted (UI) (see Figure 2). Each combination of standard and match face was presented 30 times and was counterbalanced so the match face appeared on the left for 50% and on the right for 50% of trials. The order of presentation of trials was randomised across participants. A single face, that of James Corden, was used throughout the experiment. This protocol led to each participant seeing 30 repetitions of nine match face widths in three orientation combinations (UU, II, and UI), a total of 810 trials. An opportunity to rest was presented every 54 trials.

Figure 2.

The procedure for Experiments 1 and 2, illustrating UU, UI, and II trials.

2.2. Results and discussion

The response on each trial was converted into the probability that the participant will perceive the match face as being “fatter” than the standard face. Nine participants completed the experiment with the full range of images from 8 mm thinner to 8 mm fatter. A further five participants completed the experiment using the range of 6 mm thinner to 6 mm fatter.

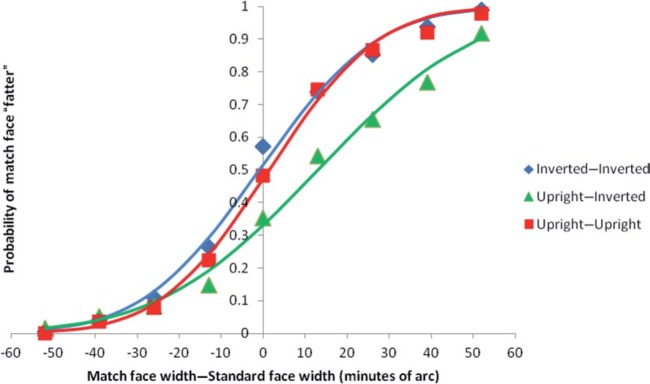

Figure 3 illustrates that for the UU and II conditions the averaged PSE was close to being veridical, deviating 0.21 mm (1.4 min arc) and −0.14 mm (1.0 min arc), respectively. The PSE for the UI condition was 2.01 mm, that is the inverted face had to be 2.01 mm (14.4 min arc) fatter than the upright one at the PSE.

Figure 3.

The probability the match face was perceived as “fatter” than the standard face for the UU, UI, and II conditions, data averaged over all participants.

For statistical analysis, the data from each of the 14 participants generated separate psychometric functions for each of the UU, II, and UI conditions. The mean of the individual PSEs is shown in Table 1.

Table 1. The mean PSE for the 14 participants. Positive values mean that inverted faces appear thinner than upright faces.

| Condition | Mean PSE (minutes) |

|---|---|

| Upright–upright | 1.65 |

| Upright–inverted | 23.4 |

| Inverted–inverted | −0.62 |

The differences between the UI condition and both the UU and II conditions were found to be significant with the Wilcoxon matched-pairs test (T values of 11 and 3 respectively, n = 14, p < 0.01 in both cases).

The results indicate that participants were accurate at judging the fatness of a face when both images were presented upright or inverted with the means being close to zero in both cases. However, there was a significant difference between both the UU and II conditions and the UI condition. The slope of the psychometric functions for the UI condition was greater than that obtained in the UU/II conditions, demonstrating that participants found matching an inverted face to an upright face a much harder task. The mean point at which the faces were perceived to match for the UI condition showed that an inverted face needed to be 4.4% wider to match the upright face. This shows that the inverted face was perceived to be thinner than its upright counterpart.

3. Experiment 2

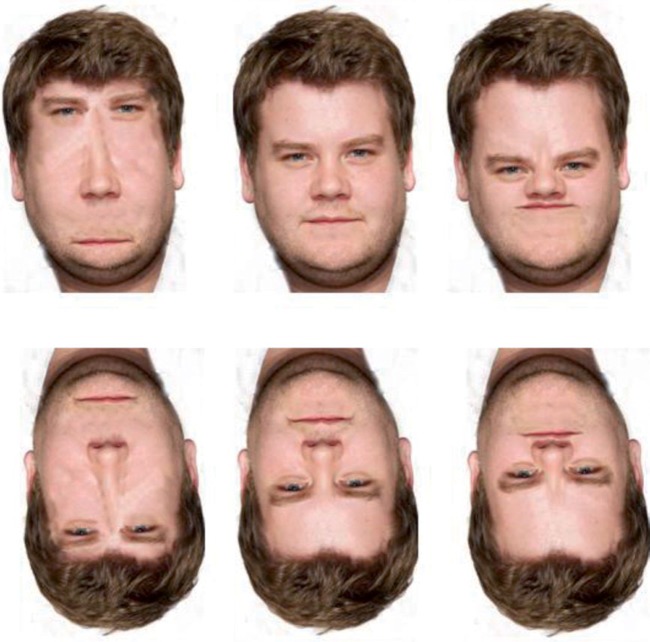

A plausible explanation of our results is that they represent an extension of the Lee and Freire (1999) effect, see their Figure 3 and our Figure 4. They presented internal facial features (eyes, nose, and mouth) within an oval framework; when the eyes and mouth were moved towards the frame the oval appeared elongated vertically, and when the eyes and mouth were moved towards the nose the oval appeared shorter and wider. If we presume that James Corden, the face in Experiment 1, has internal features that are close together, then they might distort the external face shape when upright but to a lesser extent when inverted, as holistic processing of the face is then lost. This interpretation leads to one clear prediction: faces with a relatively large distance between eyes and mouth should appear elongated when upright compared with their appearance when inverted.

Figure 4.

The face shape illusion as an example of the Lee and Freire (1999) effect. Moving the internal features further apart (left image) elongates the face and moving them closer compresses them (right image). According to Lee and Freire, inverting the faces reduces the effect. Therefore, if our subject has naturally compressed features (centre image), his face will look “fatter” when upright.

An alternative explanation comes from Valentine (2001), who reported that every face can be represented within a face-space framework. Within the framework, average faces cluster around the centre whereas distinctive faces lie at points further from the centre. Once inverted, the ability to make fine judgements about the face is greatly reduced and, as a result, it is hypothesised that faces will revert towards the average. Hence, if all faces look more average when inverted, it is not unreasonable to propose that thin upright faces should look fatter when inverted.

This interpretation might be couched in terms of a Bayesian model; let us assume that our prior is that faces are some average size. Then upright faces, which allow us to make relatively precise judgements and hence a relatively narrow likelihood, are little affected by the prior, while inverted faces, which give rise to noisier estimates, are more biased by the prior and should look more average.

Experiment 2 aimed to determine whether this is the case in that a face reverts to the average and, therefore, when inverted, a fat face would appear thinner (as shown in Experiment 1) and a thin face would appear fatter. The alternative proposal (more attuned to Lee & Freire, 1999) is that the internal features can distort the shape of the external features—and do more so with upright than inverted faces—but there is no reason why the average face should have a null effect on the external features.

3.1. Method

3.1.1. Participants

Nineteen undergraduates from the University of York took part in the experiment. The participants ranged in age from 19 to 26, with a mean age of 20.11 years. All had normal or corrected-to-normal vision.

3.1.2. Design and procedure

Using a method of adjustment, participants matched the shape of an inverted face to that of an upright version of the same face. Matching involved altering the face dimensions horizontally in steps of 1 mm (approximately 6.9 min arc). Twelve different faces, selected to provide a wide gamut of internal features (defined as the distance from the bottom of the mouth to the top of the eyes) were matched in this way and each face was matched four times. Participants sat 50 cm from the screen. The standard upright face was 108 mm (12.2 deg) in width. The experiment used a within-subjects design. Participants were required to scroll using the mouse to adjust the width of the inverted image in 1-mm steps to find the point at which they perceived the inverted face to match the standard upright face in width.

The first independent variable was the face presented and this had 12 levels of faces of different shapes. The second independent variable was the width of the inverted face and had 21 levels differing by 1 mm. The dependent variable was the point at which participants stated that the inverted face matched the standard upright face. The order of presentation of trials was randomised across participants and the trials were counterbalanced so that the standard face was presented on the right for 50% of trials and on the left on 50% of trials.

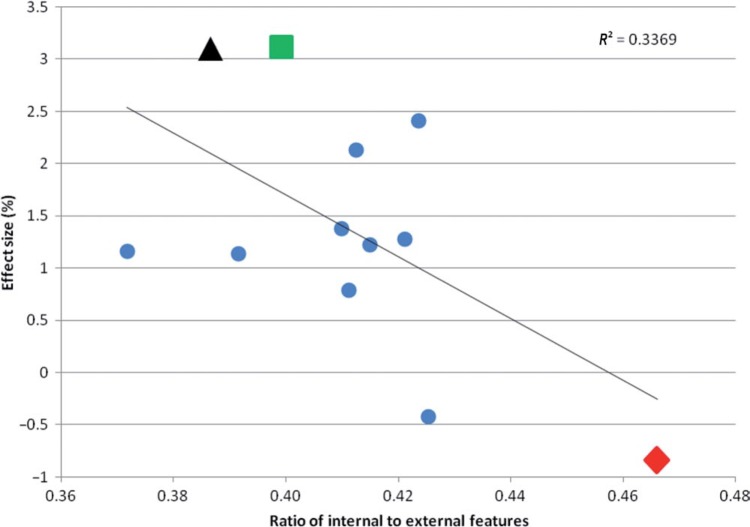

3.2. Results and discussion

The distance from the bottom of the mouth to the top of the eyes in the standardized faces gave the size of the internal facial features. This was plotted against effect size in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

The relationship between the size of the internal features of each face and the mean percentage effect of the illusion. The ratio of internal to external features is calculated from the extent of the internal features (top of eyes to bottom of mouth) as a proportion of the whole head height. James Corden's face (black triangle) shows nearly the smallest ratio of internal to external features. The extreme faces, square and diamond, are shown in Figure 6.

A Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient was computed to assess the relationship between the size of the internal features of a face and the effect size. There was a significant negative correlation (p < 0.05) between the size of the internal features and the effect size. The results show that participants perceived 10 out of the 12 inverted faces to be narrower than their upright match. There was a significant correlation between the size of the internal facial features and the size of the face shape illusion. The extent to which this occurred was dependent on the specific face presented. The results suggest that the illusion is in some way attributable to the size of the internal features within a face; see Figure 6 for the extreme examples from our sample. However, assuming that our sample of faces is representative of the population, we might have expected an equal number of positive and negative effects if inverted faces revert to some “average” (Valentine, 2001).

Figure 6.

Extreme faces from Experiment 2. On left the face that showed the largest face shape illusion (green square in Figure 5) slightly larger than James Corden (black triangle in Figure 5). On right one of only two faces that showed a “reverse” illusion, appearing thinner upright (red circle in Figure 5).

4. Experiment 3

To assess whether the internal features of a face contribute to the effects, Experiment 1 was repeated but with the internal features of the face removed. It was hypothesised that with no visible internal features there would be no difference in width perception between an upright and inverted face.

4.1. Method

4.1.1. Participants

Thirteen participants took part in the experiment. The ages ranged from 18 to 28 with a mean age of 21.08 years.

4.1.2. Design and procedure

Experiment 3 followed the same design and procedure as Experiment 1, with the only difference being that the internal features of the faces used were removed, using Photoshop software (see Figure 7).

Figure 7.

An example of the stimuli used in Experiment 3, with the internal features of the face removed.

4.2. Results and discussion

The response on each trial was converted into the probability that the participant will perceive the adjusted face as being “fatter” than the standard face. The psychometric functions for all three conditions were very similar. For all three conditions, the probability that participants perceived the adjusted face as “fatter” than the standard face was comparable at all differences in width.

Table 2 shows similar results for all three conditions. In each of the three conditions, the PSE was very close to the true match; the largest deviation (for the UI) condition shows an effect of less than 0.5%. A three-way within-subjects ANOVA was used to analyse the results. The main effect of the orientation of the two faces (UU/UI/II) was not significant: F(1.13, 13.57) = 1.30, p > 0.05.

Table 2. The mean PSE for the 13 participants. In the UI condition, the effect size was 0.34%.

| Condition | Mean PSE (minutes) |

|---|---|

| Upright–upright | −1.10 |

| Upright–inverted | 1.86 |

| Inverted–inverted | −1.58 |

The results show that when the eyes, nose, and mouth could not be used to judge the “fatness” of a face, similar results were found for all three conditions. This suggests that the internal features disrupt the ability to judge the external shape of a face when inverted. The UI condition produced very similar mean results to the UU and II conditions, all being very close to zero. This suggests that when both faces match, they are perceived to match in all conditions, a result very different from that obtained when the internal features are present.

5. General discussion

The investigation has demonstrated that the internal features of a face contribute to the perceived shape of the external features. Lee and Freire (1999) concluded that the configuration of the internal features of a face influence the perception of the shape of an oval aperture surrounding the face. The current investigation indicates that these findings could be extended to include the fact that the configuration of the internal features influences the perception of the shape of the actual face. In this regard, our results are an extension of Lee and Freire's (1999) findings.

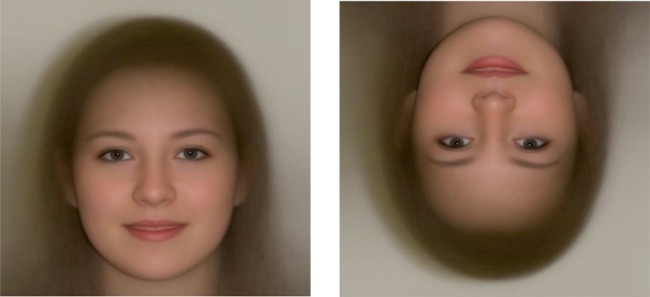

When a face is inverted, the ability to use configural processing to discriminate between faces is disrupted. Therefore, any information gained from the spacing of the features and their consequent influence on the perception of the external shape of a face should no longer be apparent when the face is inverted. Assuming that the particular internal features of James Corden's face, the stimulus for Experiment 1, are such that they equate with Lee and Freire's “short” face features, then the illusion is in direct accord with their demonstration. The key question is how the face should appear when it is inverted and configural cues have less effect on its perceived size. Experiment 2 has investigated this, finding that it appears not to be the case that upside-down faces revert to some norm or average. Had this been true we might expect as many faces to appear fatter as we find thinner when inverted. Furthermore, we could predict that an average face would produce no illusion when inverted. We have tested this idea informally, generating a composite face of 125 female undergraduates. This should show no illusion when inverted but the illusion is very apparent, the face appearing narrower upside down (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

A composite face made by averaging 125 faces still shows the illusion.

Although the illusion seems to be driven by the internal features of a face, there is no reason why the external features of the face should not make a contribution to the effect. However, Experiment 3 seems to eliminate this possibility as removing the internal features from a face effectively destroys the illusion.

In conclusion, these findings offer an insight into face perception. More specifically, this illusion provides an insight into how our perception of external features can be affected by internal features.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a research bursary from the University of York, Department of Psychology. We are grateful to Dr Tom Hartley and Dr Katie Slocombe for their help with Experiment 2 and to Rob Stone and Samantha Das for creating Figure 8.

Biography

Peter Thompson received his degree in Psychology from the University of Reading and his PhD from the University of Cambridge under the supervision of Oliver Braddick. He was awarded a Harkness fellowship, which took him to Jack Nachmias's laboratory at the University of Pennsylvania. He returned to the UK to the University of York, where he still works. In 1990, he was an NRC Senior Research Associate with Beau Watson's Vision group at NASA's Ames Research Center. He is a Royal Society—British Association Millennium Fellow and an HEFCE National Teaching Fellow. He has created the solar system (www.solar.york.ac.uk) and viperlib—a resource of images for vision scientists (www.viperlib.com). For more information, visit www-users.york.ac.uk/%C2%BBpt2.

Peter Thompson received his degree in Psychology from the University of Reading and his PhD from the University of Cambridge under the supervision of Oliver Braddick. He was awarded a Harkness fellowship, which took him to Jack Nachmias's laboratory at the University of Pennsylvania. He returned to the UK to the University of York, where he still works. In 1990, he was an NRC Senior Research Associate with Beau Watson's Vision group at NASA's Ames Research Center. He is a Royal Society—British Association Millennium Fellow and an HEFCE National Teaching Fellow. He has created the solar system (www.solar.york.ac.uk) and viperlib—a resource of images for vision scientists (www.viperlib.com). For more information, visit www-users.york.ac.uk/%C2%BBpt2.

Contributor Information

Peter Thompson, Department of Psychology, University of York, York YO10 5DD, UK; e-mail: peter.thompson@york.ac.uk.

Jennie Wilson, Department of Psychology, University of York, York YO10 5DD, UK; e-mail: jennie132@hotmail.com.

References

- Bartlett J. C., Searcy J. Inversion and configuration of faces. Cognitive Psychology. 1993;25:281–316. doi: 10.1006/cogp.1993.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce V., Young A. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1998. In the eye of the beholder: The science of face perception. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carey S., Diamond R. From piecemeal to configural representation of faces. Science. 1977;195:312–314. doi: 10.1126/science.831281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farah M. J., Tanaka J. W., Drain H. M. What causes the face inversion effect? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 1995;21:628–634. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.21.3.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp R. C., McManus C., Piggot T. Sensitivity to the displacement of facial features in negative and inverted images. Perception. 1990;19:531–543. doi: 10.1068/p190531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Künnapas T. M. The vertical–horizontal illusion in artificial visual fields. Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied. 1959;47:41–48. doi: 10.1080/00223980.1959.9916306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leder H., Bruce V. When inverted faces are recognised: The role of configural information in face recognition. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 2000;53:513–536. doi: 10.1080/713755889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K., Freire A. Effects of face configuration change on shape perception: A new illusion. Perception. 1999;28:1217–1226. doi: 10.1068/p2972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer D., Le Grand R., Mondloch C. J. The many faces of configural processing. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2002;6:255–260. doi: 10.1016/S1364-6613(02)01903-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray J. E., Yong E., Rhodes G. Revisiting the perception of upside-down faces. Psychological Science. 2000;11:492–496. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwaninger A., Ryf S., Hofer F. Configural information is processed differently in perception and recognition of faces. Vision Research. 2003;43:1501–1505. doi: 10.1016/S0042-6989(03)00171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Searcy J. H., Bartlett J. C. Inversion and processing of component and spatial relational information in faces. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 1996;22:904–915. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.22.4.904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka J. W., Farah M. J. Parts and wholes in face recognition. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1993;46A:225–245. doi: 10.1080/14640749308401045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson P. Margaret Thatcher – A new illusion. Perception. 1980;9:483–484. doi: 10.1068/p090483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson P. Eyes wide apart: Overestimating interpupillary distance. Perception. 2002;31:651–656. doi: 10.1068/p3350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentine T. Face-space models of face recognition. In: Wenger M. J., Townsend J. T., editors. Computational, geometric, and process perspectives on facial cognition: Contexts and challenges (pp 83–114) Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Yin R. K. Looking at upside-down faces. Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1969;81:141–145. doi: 10.1037/h0027474. [DOI] [Google Scholar]