Abstract

Objective

We aimed to determine to what extent covariate adjustment could affect power in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of a heterogeneous population with traumatic brain injury (TBI).

Study Design and Setting

We analyzed 14-day mortality in 9497 participants in the Corticosteroid Randomisation After Significant Head Injury (CRASH) RCT of corticosteroid vs. placebo. Adjustment was made using logistic regression for baseline covariates of two validated risk models derived from external data (IMPACT) and from the CRASH data. The relative sample size (RESS) measure, defined as the ratio of the sample size required by an adjusted analysis to attain the same power as the unadjusted reference analysis, was used to assess the impact of adjustment.

Results

Corticosteroid was associated with higher mortality compared to placebo (OR=1.25, 95% CI: 1.13, 1.39). RESS of 0.79 and 0.73 were obtained by adjustment using the IMPACT and CRASH models, respectively, which for example implies an increase from 80% to 88% and 91% power, respectively.

Conclusion

Moderate gains in power may be obtained using covariate adjustment from logistic regression in heterogeneous conditions such as TBI. Although analyses of RCTs might consider covariate adjustment to improve power, we caution against this approach in the planning of RCTs.

Keywords: covariate adjustment, prognostic targeting, strict selection, relative sample size, power in clinical trials, traumatic brain injury

1. Introduction

The randomized controlled trial (RCT) is the most important tool to estimate effects of medical interventions [1]. When trials are designed to detect unrealistically large treatment effects they are underpowered to detect more realistic moderate effects [2–4]. Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is an area where trials have frequently been underpowered [5, 6]. This is perhaps one of the reasons why current treatment guidelines do not include any class I recommendations (i.e. based on evidence from RCT) [7]. Yet, with large numbers of deaths and high global burden of disease, treatments for TBI with even modest effects could have substantial public health benefits.

RCT populations, such as those in TBI, are typically heterogeneous in baseline characteristics and prognostic risk. More heterogeneous populations may require larger RCTs to detect differences due to treatment. Alternatively, such heterogeneity can be accounted for by the use of baseline characteristics in both the design and analysis phases of trials. In the design phase these include the use of strict study enrolment criteria (strict selection) [8] or the selection of those with a specified level of risk of the outcome of interest (prognostic targeting) [9, 10] so that only individuals thought to gain most benefit from the treatment are enrolled in the trial. In the analysis phase, adjustment for baseline characteristics (covariate adjustment) can be used to account for differences between individuals in important prognostic factors of outcome [11, 12].

The three strategies of covariate adjustment, strict selection and prognostic targeting were previously applied to the IMPACT (International Mission on Prognosis and Analysis of Clinical Trials in Traumatic Brain Injury) database to assess their effect on power in six trials and three surveys of TBI, containing data from 8033 individuals [13–15]. Since no significant treatment effects were demonstrated in the constituting studies, two such effects were simulated based on the odds ratio effect measure; one equally effective in all individuals, a so-called uniform effect, the second equally effective only in individuals with risk of the outcome of 20%–80%, a so-called targeted effect. Whilst gains in power could be obtained with each of the three strategies, the design strategies of prognostic targeting and strict selection were inefficient because of up to 60% increases in study duration. Covariate adjustment led to gains around 25% for the required sample size in an earlier simulation study using the IMPACT database [16].

We aimed to evaluate the effects of covariate adjustment and related design strategies to deal with heterogeneity in a trial with a real, rather than simulated, treatment effect. We hereto analyzed data from the CRASH (Corticosteroid Randomisation After Significant Head Injury) trial of corticosteroid vs. placebo in 10,008 individuals [17], with its large, heterogeneous population.

2. Methods

2.1 Patient population and known results

The CRASH, randomized placebo-controlled trial is both the largest trial in TBI to date and the only such trial to have found a significant, albeit detrimental, treatment effect [17]. CRASH examined the effect of intravenous corticosteroid on death and disability following TBI involving 239 hospitals from 49 countries. The trial, designed to recruit 20,000 individuals in total was stopped after 10,008 individuals were randomized (5007 corticosteroid and 5001 placebo) due to elevated mortality in the corticosteroid arm. Data for the CRASH primary outcome of 14-day mortality were available for 9964 eligible individuals (4985 corticosteroid and 4979 placebo). With 1052 (21.1%) and 893 (17.9%) deaths in the corticosteroid and placebo arms respectively, the odds ratio (OR) of death at 14 days in individuals allocated corticosteroids compared to placebo was 1.22 (95% CI: 1.11–1.35, p=0.0001).

2.2 Statistical methods

Covariate adjustment can be used in the analysis phase of a trial to estimate a more individualized treatment effect [18], which is corrected for chance imbalance between treatment arms. Covariate adjustment was applied to CRASH data using two sets of covariates. The covariates considered were: age at injury; Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) which measures overall alertness; Glasgow Motor Score (GMS) which measures functional ability; pupil reactivity and major extracranial injury (MEI). First, in order to mimic a realistic scenario whereby the covariates used for adjustment were pre-specified, the covariates and their functional form specified by the IMPACT Study Group were used (i.e. age as continuous and GMS and pupil reactivity as score variables) [15]. Secondly, the covariates and their functional form specified by the CRASH Study Group were used (i.e. age as years over 40, GCS as a score variable, MEI as binary and pupil reactivity as categorical) [20] since these had the greatest prognostic strength of those examined. Details of both models are provided in the Appendix.

For ease of comparison between the two models, the 9497 eligible individuals who had complete data for all covariates were selected. Of the original 9964 individuals with outcome data, most missing covariate data resulted from incomplete information on pupil reactivity. Odds ratios were used for all analyses to measure the effect of treatment on 14-day mortality compared to placebo so that an OR > 1 corresponds to higher odds in the corticosteroid arm compared to the placebo arm, i.e. a negative effect of the corticosteroid treatment. Logistic regression was used to estimate the adjusted odds ratio and corresponding Z-score for all 9497 individuals in the study population. All analyses were based on the intention-to-treat (ITT) approach and conducted in Stata 11.

2.3 Influence on statistical power

The relative sample size (RESS) is defined as , where nref is the sample size of the reference analysis required for an arbitrary level of power and nadj is the sample size required to give that same level of power using an alternative strategy such as an adjusted analysis or analysis of a restricted portion of the study population. For example, for an RCT of 1000 individuals per arm at a specified level of power, an alternative strategy which required 900 individuals per arm to attain the same level of power would have an RESS of 0.9. In other words a relative sample size 10% smaller than the reference sample size would be needed to yield the same level of power using the alternative strategy. In practice, the RESS is calculated using Z-scores so that , where Zref and Zadj refer to the Z-scores of the treatment effect for the unadjusted reference analysis and alternative strategy, respectively (see Appendix for details). Values of RESS < 1 correspond to relative reductions in sample size, whilst values of RESS > 1 to relative increases in sample size.

The RESS measure is related to the previously used reduction in sample size (RSS) measure [12, 15, 16] by RSS = 100 × (1-RESS). The RSS, which measures the percentage reduction in sample size required for an alternative strategy to attain the same level of power as the unadjusted reference analysis, is a useful tool to interpret the RESS, as shown in the example above.

The effect of covariate adjustment on relative sample sizes was evaluated using the RESS measure. The Z-score of the reference model, Zref, was obtained from the unadjusted analysis for the reference population of the 9497 individuals with complete covariate data. The Z-score for each of the two models for covariate adjustment, Zadj, was obtained by adjusted logistic regression applied to the same sample of 9497 individuals.

Alternatively, the effect of covariate adjustment can be evaluated in terms of the gain in power (i.e. larger effective sample size) achievable when covariate adjustment is applied to the original study population with no reduction in sample size when the effect of adjustment is summarised by the RESS. See Appendix for details.

2.4 Adjusted OR and implications for influence on statistical power

Chance imbalances in baseline characteristics affect the magnitude of the adjusted OR obtained by covariate adjustment. For example, 1% more of the corticosteroid arm had MEI compared to the placebo arm and the regression coefficient of MEI in the adjusted CRASH analysis was 0.23. The impact of imbalance on the estimated treatment effect was calculated as coefMEI × differenceMEI = 0.23 × 0.01= 0.0023(see [21] for additional details). A corrected Z-score, Zadj, corr, was calculated and used to calculate an imbalance-corrected RESS, RESScorr, which was used as the primary measure of the effects of covariate adjustment for the two different models. Bias-corrected bootstrapping (2000 replications) was used to obtain confidence intervals for both RESS measures [22].

2.5 Design strategies used for comparison

The IMPACT Study Group hypothesised that (1) those who met stricter inclusion criteria than the original study inclusion criteria, and, (2) those in the middle of the risk spectrum (20% <risk< 80%) might benefit most from treatments in TBI (i.e. that there may be a treatment-prognosis interaction) [15] resulting in two sub-groups of patients termed strict selection and prognostic targeting. Those two design strategies were applied to the CRASH trial study population to determine what proportion of the population would be excluded and to determine the impact on the estimated treatment effect. In both cases, the unadjusted odds ratio and corresponding Z-score were evaluated for the two sub-groups of individuals who met the criteria.

Strict selection was defined by the more restrictive selection criteria specified by the IMPACT Study Group [15]: time window between injury and admission to study hospital ≤ 8 hours; age at injury ≤65 years; ≥1 reactive pupil; motor score > 1; GCS ≤8. For prognostic targeting, the three covariates (i.e. age, GMS and pupil reactivity) and their corresponding regression coefficients from the validated risk model of the IMPACT Study Group [19] were used to calculate the risk of death at 6 months so that only those with risk in the range of 20%–80% were retained in the sub-group. Details, including coefficients, are provided in the Appendix.

3. Results

Baseline distributions of the covariates were generally well balanced between the treatment groups (Table 1). Increased age, lower (more severe) GCS, lower (more severe) GMS and worse pupil reactivity were associated with increased mortality (Table 1). Corticosteroid was associated with 25% higher odds of 14-day mortality compared to placebo (OR=1.25, 95% CI: 1.13, 1.39). The Z-score corresponding to that OR was 4.23 from unadjusted analyses of data from all 9497 individuals. This analysis is referred to as the reference analysis (Table 2).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and 14-day mortality by treatment arm and prognostic strength of baseline characteristics for the CRASH trial study population (n=9497)

| Characteristic | Corticosteroid (n=4745) | Placebo (n=4752) | Odds ratio (95% CI) of 14-day mortality |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Deaths | n | Deaths | ||

| Deaths at 14-days | - | 976 (20.6%) | - | 816 (17.2%) | - |

| Age (years) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 36.9 (17.0) | - | 36.9 (17.0) | - | - |

| <20 | 611 (12.9%) | 80 | 564 (11.9%) | 61 | 1 (Reference) |

| <30 | 1387 (29.2%) | 222 | 1472 (31.0%) | 212 | 1.31 (1.07,1.61) |

| <40 | 972 (20.5%) | 170 | 961 (20.2%) | 134 | 1.37 (1.10,1.70) |

| <50 | 727 (15.3%) | 156 | 703 (14.8%) | 130 | 1.83 (1.47,2.28) |

| <60 | 491 (10.4%) | 123 | 462 (9.7%) | 80 | 1.98 (1.57,2.51) |

| 60+ | 557 (11.7%) | 225 | 590 (12.4%) | 199 | 4.30 (3.48,5.32) |

| Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) | |||||

| Mild (13–14) | 1419 (29.9%) | 60 | 1500 (31.6%) | 58 | 1 (Reference) |

| Moderate (9–12) | 1501 (31.6%) | 195 | 1426 (30.0%) | 132 | 2.99 (2.40,3.71) |

| Severe (3–8) | 1825 (38.5%) | 721 | 1826 (38.4%) | 626 | 13.88 (11.41,16.89) |

| Glasgow Motor Score (GMS) | |||||

| Localising /obeys commands (5–6) | 3229 (68.1%) | 356 | 3266 (68.7%) | 267 | 1 (Reference) |

| Normal (4) | 585 (12.3%) | 160 | 581 (12.2%) | 120 | 2.98 (2.54,3.49) |

| Abnormal (3) | 324 (6.8%) | 138 | 312 (6.6%) | 132 | 6.95 (5.82,8.30) |

| Extending (2) | 243 (5.1%) | 145 | 241 (5.1%) | 142 | 13.73 (11.25,16.76) |

| None (1) | 364 (7.7%) | 177 | 352 (7.4%) | 155 | 8.15 (6.89, 9.64) |

| Pupil reactivity | |||||

| Both reactive | 4054 (85.4%) | 574 | 4059 (85.4%) | 457 | 1 (Reference) |

| One reactive | 292 (6.2%) | 128 | 315 (6.6%) | 116 | 4.62 (3.88,5.50) |

| Neither reactive | 399 (8.4%) | 274 | 378 (8.0%) | 243 | 13.66 (11.61,16.07) |

| Major extracranial injury | |||||

| No | 3665 (77.2%) | 668 | 3718 (78.2%) | 592 | 1 (Reference) |

| Yes | 1080 (22.8%) | 308 | 1034 (21.8%) | 224 | 1.63 (1.46,1.83) |

Table 2.

Effect of covariate adjustment on the estimated effect of corticosteroid on 14-day mortality for the CRASH trial study population (n=9497)

| Strategy | OR | (95% CI) | βa | (SE[β]) | Δ βb | Δ SE[β] c | Z | βcorrd | Δ βcorrb | Zcorre | p-value | RESS | RESScorrf | (95% CI)g |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference (Unadjusted) | 1.25 | (1.13,1.39) | 0.222 | (0.053) | - | - | 4.226 | - | - | - | <0.0001 | - | - | |

| Covariate Adjustment | ||||||||||||||

| IMPACT modelh | 1.32 | (1.17,1.48) | 0.274 | (0.060) | +23% | +14% | 4.559 | 0.278 | +25% | 4.619 | <0.0001 | 0.86 | 0.79 | (0.65,0.93) |

| CRASH modeli | 1.33 | (1.18,1.50) | 0.286 | (0.062) | +28% | +18% | 4.615 | 0.306 | +38% | 4.933 | <0.0001 | 0.84 | 0.73 | (0.58,0.87) |

Estimated coefficient from logistic regression model, i.e. log(OR).

Relative difference of βadj, coefficient from adjusted analysis, compared to βref, coefficient from reference analysis: (βadj − βref) / βref.

Relative difference of SE[βadj], SE of coefficient from adjusted analysis, compared to SE[βref], SE of coefficient from reference analysis: (SE[βadj] − SE[βref]) / SE[βref].

Imbalance-corrected regression coefficient.

Imbalance-corrected Z-score.

Imbalance-corrected relative sample size, RESScorr = (Zref / Zadj,corr)2, where Zadj,corr is from the adjusted analysis and is corrected for chance imbalance in covariates.

Obtained by bias-corrected bootstrapping (2000 replications).

Once the small chance baseline imbalance in favour of placebo was accounted for, whereby those in the corticosteroid arm had slightly worse prognosis (Table 1), RESScorr of 0.79 (95% CI: 0.65, 0.93) and 0.73 (95% CI: 0.58, 0.87) were obtained for the IMPACT and CRASH models, respectively. In other words, relative sample sizes 21% and 27% smaller would be required to attain the same level of power of the unadjusted reference analysis for the IMPACT and CRASH models, respectively. The effect of corticosteroid was detrimental as seen from the adjusted odds ratios and corresponding 95% CI of 1.32 (95% CI: 1.17, 1.48) and 1.33 (95% CI: 1.18, 1.50) for the IMPACT and CRASH models, respectively.

The effects of both models can be examined via the change in regression coefficient of the adjusted model, specifically of the imbalance-corrected regression coefficient, and the associated change in standard error (SE). In both cases the increases in SE (+14% and +18% for IMPACT and CRASH, respectively) are smaller than the increases in regression coefficient (+25% and +38% for IMPACT and CRASH, respectively) so that the imbalance-corrected Z-scores of the adjusted analyses are larger (Zadj,corr = 4.619 and 4.933 for IMPACT and CRASH, respectively) than that of the unadjusted reference analysis (Z=4.226) resulting in RESS < 1.

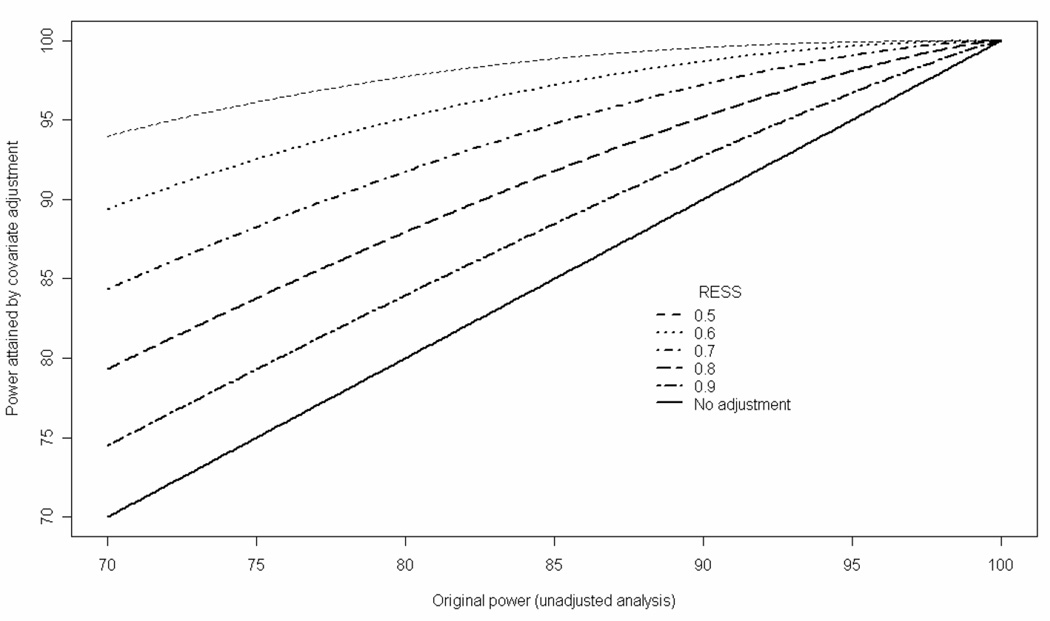

It is informative to consider what gain in power (i.e. larger effective sample size) can be achieved when covariate adjustment is applied to the original study population. When covariate adjustment achieves an RESS of 0.73, 80% power of the unadjusted analysis would increase to 91% (Figure 1). Similarly, an increase from 80% to 88% power would be achieved for an RESS of 0.79 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Statistical power attained by covariate adjustment vs. original power of unadjusted analysis for different values of RESS at the 5% significance level.

When the strict selection criteria of the IMPACT Study Group [15] were applied to the CRASH data, most individuals were excluded resulting in a sub-group of 2326 of the original 9497 individuals (Table 3). For this strategy, the unadjusted OR was larger than the unadjusted reference OR (1.33 vs. 1.25), yet the 95% CI was wider (1.11 to 1.60 vs. 1.13 to 1.39) as a result of lower precision of the effect estimate (Table 3). Similarly, prognostic targeting using the IMPACT risk model [19] identified 2456 individuals with intermediate risk (20%–80%). Compared to the reference analysis for the complete data set of 9497 individuals, an OR closer to the null was estimated. Moreover, with an unadjusted OR of 1.16 (95% CI: 0.99, 1.37) the effect of corticosteroid was not statistically significant. In both cases, unlike covariate adjustment, the relative change in the SE of the regression coefficient compared to the unadjusted reference analysis was much larger than the relative change of the regression coefficient (Table 3) with the large increase in SE primarily a result of the considerably smaller sample sizes of the sub-groups.

Table 3.

Effect of two design strategies (strict selection and prognostic targeting) on the estimated effect of corticosteroid on 14-day mortality for the CRASH trial study population (n=9497)

| Strategy | OR | (CI) | β a | (SE[β]) | Δβb | ΔSE[β]c | Z | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference (Unadjusted) (n=9497) | 1.25 | (1.13,1.39) | 0.222 | (0.053) | - | - | 4.226 | <0.0001 |

| IMPACT strict selection d (n=2326) | 1.33 | (1.11,1.60) | 0.286 | (0.094) | +29% | +79% | 3.035 | 0.002 |

| IMPACT Prognostic targetinge (n=2456) | 1.16 | (0.99,1.37) | 0.152 | (0.081) | −32% | +54% | 1.869 | 0.062 |

Estimated coefficient from logistic regression model, i.e. log(OR)

Relative difference of βalt, coefficient from alternative analysis of restricted study population, compared to βref, coefficient from reference analysis: (βalt − βref) / βref

Relative difference of SE(βalt), SE of coefficient from alternative analysis of restricted study population, compared to SE(βref), SE of coefficient from reference analysis: (SE[βalt] − SE[βref]) / SE[βref]

Time window between injury and admission to study hospital ≤ 8 hours; age at injury ≤65 years; ≥1 reactive pupil; GMS > 1; GCS ≤8.

4. Discussion

This study presents comparisons of two models for covariate adjustment to increase power in RCTs by accounting for heterogeneity between individuals. It is the first comparison in a large trial in TBI which had shown evidence of a treatment difference whereby an external risk model could be applied to real patient data. Relative reductions in sample size were observed in both cases, with a natural advantage of the CRASH risk model (RESScorr of 0.73 vs. 0.79 for the IMPACT model). Equivalently, covariate adjustment can increase the statistical power for the detection of a treatment effect for a given sample size.

Strengths of this study include that real patient data was used (both covariate and outcome) from the largest trial in TBI to date and the only such trial to have found a significant, albeit detrimental, treatment effect. In addition an external risk model (IMPACT) was used to assess the effect of covariate adjustment and there were minimal missing data (i.e. 5%) largely as a result of challenges in measuring pupil reactivity in a clinical setting. In also using an internal risk model it was possible to obtain a plausible largest effect of covariate adjustment in the CRASH data.

Limitations of this study include that we have analyzed data from a single, albeit large, RCT and have thus not been able to assess the performance of the strategies across replications of data sets [12, 15], nor to assess the role of the magnitude and direction of the treatment effects. Likewise we did not systematically consider differential treatment effects according to prognostic risk, which could affect the ability of covariate to improve power of analyses. Previous analyses simulated a beneficial treatment effect [12, 15, 16], whereas a detrimental treatment effect was observed in the CRASH trial. Individuals with missing covariate data were excluded from the analyses so that data from 9497 individuals were analyzed rather than that of 9964 individuals in the original ITT analyses [17]. In practice, an external prognostic model and/or set of covariates for adjustment would be pre-specified for the outcome of interest (i.e. 14-day mortality in the present analysis). For this analysis an external risk model for 6-month mortality only was available. Nonetheless, most deaths (e.g. 84% in the case of CRASH) occur within 14 days of trauma and therefore the impact of a risk factor is likely to be similar.

General issues related to covariate adjustment in RCTs have been recently discussed via a systematic review of the practice in four general medical journals in which 39 of 114 articles reported adjusted results [23]. In particular, when covariate adjustment of the OR effect measure is performed, characteristics of the adjusted measure should be considered as well as properties of logistic regression modelling. In contrast to effects measured by the unadjusted OR for the reference model, covariate adjustment yields adjusted OR which should be interpreted conditionally on the covariates included in the model rather than at a population level unlike adjustment in linear regression modelling or binomial regression where adjusted treatment effects have the same population-level interpretation as unadjusted treatment effects [24, 25]. For example, adjustment for age would produce OR for a specific age. On the other hand the unadjusted OR of the reference analysis could be interpreted as an average effect for the whole study population.

Further properties of logistic regression model relate to the so-called non-linearity effect whereby, on average, the conditional effects estimated by the adjusted model are further from the null than the marginal effects (with their population-level interpretation) estimated by the unadjusted model even if covariates are perfectly balanced between treatment groups [26–28]. For example, suppose that there were equal proportions of individuals with MEI in the two arms of the CRASH trial. If an unadjusted OR of 1.2 was estimated then the MEI-adjusted OR is expected to be further from the null effect of an OR of 1, for example at 1.24. Moreover, the MEI-adjusted OR of 1.24 would be interpreted as the OR given MEI status is known whereas the unadjusted OR of 1.2 would be interpreted at a population-level i.e. over all individuals.

A population-level average interpretation of an effect measure is usually of most interest in public health. Adjusted ORs obtained by covariate adjustment via logistic regression are not interpretable in such a fashion. In contrast, the relative risk (RR) effect measure does not alter the population-level interpretation of the unadjusted RR. However, algorithms used to fit binomial regression models to estimate adjusted RRs do not always converge and the assumption of a constant relative risk across strata may not be tenable. Future work is required on the effect of covariate adjustment when the relative risk is used as a measure of the impact of treatment. Simulation studies could be used to assess the performance of various strategies across replications of data sets. Similarly, different treatment effects of a uniform and targeted nature could be simulated including beneficial effects using, for example, the CRASH covariate data.

The current findings regarding covariate adjustment are in line with previous work [12, 15]. The design strategies of prognostic targeting and strict selection resulted in of exclusion of large proportions (approximately 75%) of the CRASH population. For subsets of approximately 25% of the original trial population, recruitment of the original trial size would take up to four times as long; representing a trial of duration of up to 20 years in the case of CRASH (at least if no further centres were recruited). Similarly, the authors of previous work [15] advised against the use of prognostic targeting and strict selection as a result of the increased study duration although gains in power were observed in that work since study populations of the same size as the original sample were simulated.

As a consequence of the reduced recruitment rates and subsequent extended study duration, covariate adjustment is to be preferred over these two design strategies [15]. Further, strict inclusion criteria & prognostic targeting require well established risk factors, which are not always known. Importantly, were a trial planned based on restrictive inclusion criteria, the results could only be reliably generalized to a broader population when the treatment effect was the same for eligible and ineligible individuals, something which could not be determined from the trial itself.

Although covariate adjustment can be used to attain the same level of power with reduced sample size, we do not advocate its use for the planning of smaller trials. Such use in the planning phase would require pre-specification of the functional form of baseline covariates including whether to categorise continuous covariates (with caveats related to loss in power [28]) and possible interactions of those covariates. Yet pre-specifying an appropriate model in advance is not guaranteed to provide the best form in practice. Instead of considering how covariate adjustment might be used to reduce sample sizes required, it is useful to consider the greater power attainable when covariate adjustment is applied to the original study population (Figure 1). Although the power of adjusted analyses may increase, it may still be insufficient to detect plausible treatment effects had the trial been underpowered initially. For example, for unadjusted power of 70%, covariate adjustment with an RESS of 0.8 (i.e. of the order of that observed in the present study) would yield a power that is still lower than 80%.

In conclusion, covariate adjustment may be a viable tool to improve power in RCTs in heterogeneous populations. Nonetheless, all gains are relative and may not result in trials which are sufficiently powered to answer the primary research question. Researchers should remain aware that OR obtained by covariate adjustment should be interpreted conditional on covariate values whereas unadjusted OR can be interpreted at the population level. We advocate the use of pre-specified covariate adjustment in the analysis but caution against its use in the design phase of RCTs so that sample size calculations do not account for covariate adjustment.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all CRASH collaborators for their involvement in the trial. Professor Chris Frost provided many helpful comments and advice on an earlier manuscript and the methods. Two reviewers provided helpful comments and references which greatly improved the final version. Financial support (EWS) was provided by NIH NS 42691.

Appendix

Derivation of relative sample size (RESS)

In general the sample size required for arbitrary power β and statistical significance α is known to be proportional to , where Z is the expected value of the Z-score of treatment effect. Suppose that Z is changed from Zref to Zadj with a corresponding change in sample size from nref to nadj. Then the relative sample size (RESS) is given by which can be estimated as . We note that the measure is related to that used by Roozenbeek et al. [15] and Hernández et al. [12, 16], namely the reduction in sample size (RSS), which measures the relative proportional reduction in sample size and is defined by , which can be estimated as , i.e. 100×[1−RESS]. For example, an RESS of 0.9 corresponds to a RSS of 10% i.e. a relative reduction in sample size of 10%.

Derivation of power attained by covariate adjustment for fixed study population size at different levels of RESS

In general the sample size, n, required to detect a Z-score, Z, for arbitrary power β and statistical significance α are related by Then for fixed sample size n if βref and βadj denote the power to detect Zref and Zadj, respectively, then . Equivalently, which yields . Therefore, for a fixed sample size and fixed level of significance, the effect of covariate adjustment as measured by the RESS gives power βadj which can be derived using quantiles of the expression above.

Models used for covariate adjustment

The covariates considered for adjustment were age at injury; Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) with 15 possible levels of which 12 were observed in eligible trial participants; Glasgow Motor Score (GMS) with five levels (from best to worst: localising/obeys commands; normal flexion; abnormal flexion; extending; none); pupil reactivity with three levels (from best to worst: both reactive, one unreactive, both unreactive) and major extracranial injury (MEI) as a binary variable. We use p to denote the probability of 14-day mortality.

IMPACT Study Group adjustment

The model described in the final paragraph of page 2684 of [15] was used. In particular, the following model, shown with estimated coefficients:

logit(p) = −3.8670+ 0.2744treatment + 0.2728age +0.4430motor + 0.9567pupil,

was used i.e. age was modelled as a continuous variable with motor score and pupil reactivity as score variables (from best to worst).

CRASH Study Group adjustment

The model described in [20] was used. In particular, the following model, shown with estimated coefficients:

logit(p) = −4.5836 + 0.2857treatment + 0.0481age40 + 0.7830pupilone unreactive + 1.4934pupilboth unreactive + 0.2740GCS + 0.2272MEI,

was used with age40 as age over 40 years (equal to 0 for those younger than 40), and pupilone unreactive & pupilboth unreactive indicators of one unreactive pupil or both unreactive pupils, respectively i.e. age (over 40 years) was modelled as a continuous variable, GCS as a score variable (from best to worst), pupil reactivity as categorical and MEI in its natural form as a binary variable.

Risk model used for prognostic targeting

The IMPACT Study Group risk model for 6-months mortality was used. Details can be found in Figure 1 of [19]. In particular, the following scores (shown in brackets) were assigned to variable levels:

Age: ≤30 (0); 30–39 (1); 40–49 (2); 50–59 (3); 60–69 (4) and 70+ (5); Motor score: None/extension (6); Abnormal flexion (4); Normal Flexion (2); Localizes/obeys (0); Untestable/missing (3); Pupil reactivity: Both reactive (0); One pupil reacted (2); No pupil reacted (4). A score was calculated for each individual and their risk estimated using 1/(1+exp(score) ) where score = −2.55 +0.275×score.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pocock S. Clinical Trials: A Practical Approach. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aberegg SK, Richards DR, O’Brien JM. Delta inflation: a bias in the design of randomized controlled trials in critical care medicine. Crit Care. 2010;14:R77. doi: 10.1186/cc8990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halpern SD, Karlawish JH, Berlin JA. The continuing unethical conduct of underpowered clinical trials. JAMA. 2002;288:358–362. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roozenbeek B, Lingsma HF, Steyerberg EW, Maas AIR for the IMPACT Study Group. Underpowered trials in critical care medicine: how to deal with it? Crit Care. 2010;14:423. doi: 10.1186/cc9021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dickinson K, Bunn F, Wentz R, Edwards P, Roberts I. Size and quality of randomized controlled trials in head injury: review of published studies. BMJ. 2000;320:1308–1311. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7245.1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maas AI, Steyerberg EW, Murray GD, Bullock R, Baethmann A, Marshall LF, Teasdale GM. Why have recent trials of neuroprotective agents in head injuries failed to show convincing efficacy? A pragmatic analysis and theoretical considerations. Neurosurgery. 1999;44:1286–1298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brain Trauma Foundation. Joint Project of the Brain Trauma Foundation and American Association of Neurological Surgeons (AANS), Congress of Neurological Surgeons (CNS) and AANS/CNS Joint Section on Neurotrauma and Critical Care. Guidelines for the Management of Severe Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Neurotrauma. (3rd Edition) 2007;24(Supplement 1) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saatman KE, Duhaime AC, Bullock R, Maas AIR, Valadka A, Manley GT Workshop Scientific Team And Advisory Panel Members. Classification of traumatic brain injury for targeted therapies. J Neurotrauma. 2008;25:719–738. doi: 10.1089/neu.2008.0586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Machado SG, Murray GD, Teasdale GM. Evaluation of designs for clinical trials of neuroprotective agents in head injury. European Brain Injury Consortium. J Neurotrauma. 1999;16:1131–1138. doi: 10.1089/neu.1999.16.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weir CJ, Kaste M, Lees KR Glycine Antagonist in Neuroprotection (GAIN) International Steering Committee and Investigators. Targeting neuroprotection clinical trials to ischemic stroke patients with potential to benefit from therapy. Stroke. 2004;35:2111–2116. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000136556.34438.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Altman DG. Adjustment for covariate imbalance. In: Redmond C, Colton T, editors. Biostatistics in Clinical Trials. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; 2001. pp. 122–127. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hernández AV, Steyerberg EW, Habema JDF. Covariate adjustment in randomized controlled trials with dichotomous outcomes increases statistical power and reduces sample size requirements. J Clin Epid. 2004;57:454–460. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2003.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maas AI, Marmarou A, Murray GD, Teasdale SG, Steyerberg EW. Prognosis and clinical trial design in traumatic brain injury: the IMPACT study. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24:232–238. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marmarou A, Lu J, Butcher I, McHugh GS, Mushkadini NA, Murray GD, Steyerberg EW, Maas AIR. IMPACT database of traumatic brain injury: design and description. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24:232–238. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roozenbeek B, Maas AIR, Lingsma HF, Butcher I, Lu J, Marmarou A, McHugh GS, Weir J, Murray GD, Steyerberg EW Impact Study Group. Baseline characteristics and statistical power in randomized controlled trials: Selection, prognostic targeting, or covariate adjustment? Crit Care Med. 2009;37:2683–2690. doi: 10.1097/ccm.0b013e3181ab85ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hernández AV, Steyerberg EW, Butcher I, Mushkadini N, Taylor GS, Murray GD, Marmarou A, Choi SC, Lu J, Habbema JD, Maas AI. Adjustment for strong predictors of outcome in traumatic brain injury trials: 25% reduction in sample size requirements in the IMPACT study. J Neurotrauma. 2006;23:1295–1303. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.23.1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.CRASH trial collaborators. Effect of intravenous corticosteroids on death within 14 days in 10,008 adults with clinically significant head injury (MRC CRASH trial): randomized placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:1321–1328. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17188-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hauck WW, Anderson S, Marcus SM. Should we adjust for covariates in nonlinear regression analyses of randomized trials? Control Clin Trials. 1998;19:249–256. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(97)00147-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steyerberg EW, Mushkudiani N, Perel P, Butcher I, Lu J, McHugh GS, Murray GD, Marmarou A, Roberts I, Habbema JDF, Maas AIR. Predicting outcome after traumatic brain injury: Development and international validation of prognostic scores based on admission characteristics. PLoS Medicine. 2008:425–429. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MRC CRASH trial collaborators. Predicting outcome after traumatic brain injury. BMJ. 2008;336:425–429. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39461.643438.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steyerberg EW, Bossuyt PMM, Lee KL. Clinical trials in acute myocardial infarction: Should we adjust for baseline characteristics? Am Heart J. 2000;139:745–751. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(00)90001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davison AC, Hinkley D. Bootstrap Methods and their Application. 8th edition. Cambridge: Cambridge Series in Statistical and Probabilistic Mathematics; 2006. Bootstrap Methods and their Application. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Austin PC, Manca A, Zwarenstein M, Juurlink DN, Stanbrook MB. A substantial and confusing variation exists in handling of baseline covariates in randomized controlled trials: a review of trials published in leading medical journals. J Clin Epid. 2010;63:142–153. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steyerberg EW, Eijkemans MJC. Heterogeneity bias: The difference between adjusted and unadjusted effects. Med Decis Making. 2004;24:102–104. doi: 10.1177/0272989X03262285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Groenwold RH, Moons KG, Peelen LM, Knol MJ, Hoes AW. Reporting of treatment effects from randomized trials: A plea for multivariable risk ratios. Contemp Clin Trials. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2010.12.011. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ford I, Norrie J. The role of covariates in estimating treatment effects and risk in long-term clinical trials. Stat Med. 2002;21:2899–2908. doi: 10.1002/sim.1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gail MH, Wieand S, Piantadosi S. Biased estimates of treatment effect in randomized experiments with nonlinear regressions and omitted covariates. Biometrika. 1984;71:431–444. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robinson LD, Jewell NP. Some surprising results about covariate adjustment in logistic regression models. Internat Stat Rev. 1991;58:227–240. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang PG, Chen DG, Roe T. Choice of Baselines in Clinical Trials: A Simulation Study from Statistical Power Perspective. Commun Stat Simulat. 201039:1305–1317. [Google Scholar]