Abstract

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the outcome prediction power of classical prognostic factors along with surrogate approximation of genetic signatures (AGS) subtypes in patients affected by localized breast cancer (BC) and treated with postoperative radiotherapy. We retrospectively analyzed 468 consecutive female patients affected by localized BC with complete immunohistochemical and pathological information available. All patients underwent surgery plus radiotherapy. Median follow-up was 59 months (range, 6–132) from the diagnosis. Disease recurrences (DR), local and/or distant, and contralateral breast cancer (CBC) were registered and analyzed in relation to subtypes (luminal A, luminal B, HER-2, and basal), and classical prognostic factors (PFs), namely age, nodal status (N), tumor classification (T), grading (G), estrogen receptors (ER), progesterone receptors and erb-B2 status. Bootstrap technique for variable selection and bootstrap resampling to test selection stability were used. Regarding AGS subtypes, HER-2 and basal were more likely to recur than luminal A and B subtypes, while patients in the basal group were more likely to have CBC. However, considering PFs along with AGS subtypes, the optimal multivariable predictive model for DR consisted of age, T, N, G and ER. A single-variable model including basal subtype resulted again as the optimal predictive model for CBC. In patients bearing localized BC the combination of classical clinical variables age, T, N, G and ER was still confirmed to be the best predictor of DR, while the basal subtype was demonstrated to be significantly and exclusively correlated with CBC.

Keywords: breast cancer, multivariable model, bootstrapping, contralateral breast cancer

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer (BC) is the most frequent cancer in Europe with an incidence of more than 400 000 cases and a mortality rate of about 130 000 cases yearly [1]. The treatment for localized BC consists of mastectomy or breast-conserving surgery and radiotherapy, coupled or not with adjuvant drug therapy. At the present, also thanks to the diffusion of screening programs allowing an early detection of BC, the above therapies are able to cure most patients with localized disease.

Nevertheless, after curative primary treatment of localized BC, local or distant disease relapse is possible, even several years after diagnosis. Women affected by BC also have an increased risk of developing contralateral breast cancer (CBC) over their lifetime [2]. Local recurrences and CBC have been shown to be associated with an increase of BC mortality [3]. Identification of BC-bearing patients with an increased risk of a defined event could surely help to hone follow-up and/or therapy strategies.

Prognostic evaluation of BC patients can be based either on classical clinical variables, such as age, tumour size, nodal status, grading, hormone receptors and erb-B2 status [4, 5], or on genetic signatures that define the biological level of aggressiveness of the disease through the assessment of the cancer cells gene expression profile [6]. Few previous studies have evaluated the interaction between the classical clinical variables and the genetic signature subtypes providing an improved predictive value in lymph node-negative patients [7–9]. The value of the genetic subclassification of the disease is well recognized, nevertheless economical and organizational requirements avoid the routinary use of microarrays for its assessment. As a result, this kind of information is less commonly available in clinical practice. Lately, however, on the basis of the pattern of the receptors status [estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PgR), erb-B2], a surrogate approximation of the genetic classification has been proposed [10–12]. This methodology recognizes four subtypes of BC, namely luminal A (ER + and/or PgR + , and erb-B2–), luminal B (ER + and/or PgR + , and erb-B2 + ), HER-2 (ER–, PgR– and erb-B2 + ), and basal (ER–, PgR– and erb-B2–).

In this study, for BC patients treated with postoperative radiotherapy, we have evaluated the impact of classical clinical variables, well-established as prognostic factors (PFs), in conjunction with a surrogate approximation of genetic signatures (AGS) subtypes based on hormone receptors and erb-B2 status. The use of PFs and AGS subtypes in building multivariable prediction models was assessed.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients and data collection

A total of 468 female patients affected by localized BC and treated at the Radiation Oncology Department of the University “Federico II” of Naples between January 1999 and December 2006 were included in the study. All patients signed an informed consent about the anonymous use of their data, and the ethical committee of our institution approved the study. Patient median age at diagnosis was 53 years (range, 27–84). Of the 468 patients, 32 (6.8%) underwent mastectomy while 436 (93.2%) had breast-conserving surgery. The axillary nodal dissection and the sentinel lymph node procedure were performed in 353 (75.4%) and 80 (17%) patients, respectively. Radiation therapy (RT) was administered by photon/electron beams from a linear accelerator with a total dose of 50–60 Gy in 2 Gy daily fractions. Adjuvant chemotherapy, hormonal therapy or both were administered to 68, 192 and 194 patients respectively. Of note, at that time, the monoclonal antibody against the erb-B2 membrane protein trastuzumab was not part of the adjuvant treatment for patients with tumours positive for the expression of that gene, and adjuvant pharmacological therapy was not considered in our analysis.

Before treatment, all patients underwent bilateral mammogram and/or breast ultrasound scan. Staging was performed by chest X-ray, abdominal ultrasound and bone-scan. The results of clinical and pathological staging were reported according to the TNM American Joint Committee on Cancer 7 (AJCC 7) staging system. Hormonal receptor (HR) status and erb-B2 overexpression were performed by immunohistochemistry. ER and PgR were considered positive when at least 10% of the tumor cells showed staining of ER/PgR in the nuclei [13]. The erb-B2 tests were chart reported as follows: 0–1 + = < 10% = negative; 2 + = 10% to 30% = indeterminate; and 3 + = > 30% = positive. The cases with erb-B2 test results reported as indeterminate were further analyzed by fluorescence in situhybridization (FISH) testing. In the absence of the FISH test, the indeterminate cases were excluded from the analysis. Data on clinical variables recognized as PFs were collected. These included age (≤ 50 vs > 50), nodal status (N + vs N-), tumor classification (T1 vs >T1), and grading (G1–2 vs G3), ER and PgR, and erb-B2 status. The staging and immunohistochemical features of the entire cohort are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Staging and histopathological patient features

| Characteristics | % | n | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| ≤50 | 58.4 | 269 | |

| >50 | 42.5 | 199 | |

| Stage | |||

| 0 | 5.3 | 25 | |

| I | 47.6 | 223 | |

| II | 36.3 | 170 | |

| III | 9 | 42 | |

| NA | 1.7 | 8 | |

| pT | |||

| ≤pT1 | 70.7 | 331 | |

| >pT1 | 27.6 | 129 | |

| NA | 1.7 | 8 | |

| Nodal status | |||

| N0 | 66.2 | 310 | |

| N1 | 25.2 | 118 | |

| N2 | 6 | 28 | |

| N3 | 1.9 | 9 | |

| NA | 0.6 | 3 | |

| Histotype | |||

| Ductal | 79.7 | 373 | |

| Lobular | 10 | 47 | |

| Other | 10.3 | 48 | |

| Grading | |||

| G1 | 8.8 | 41 | |

| G2 | 39.7 | 186 | |

| G3 | 41.7 | 195 | |

| NA | 9.8 | 46 | |

| Immunohistochemistry | |||

| ER + | 76.3 | 357 | |

| ER– | 23.7 | 111 | |

| PgR + | 71.4 | 334 | |

| PgR– | 28.6 | 134 | |

| erb-B2 + | 18.6 | 87 | |

| erb-B2– | 81.4 | 381 | |

| AGS | |||

| Luminal A | 67.7 | 317 | |

| Luminal B | 13.2 | 62 | |

| HER-2 | 5.3 | 25 | |

| Basal | 13.7 | 64 |

A further classification of patients according to a surrogate AGS and recognizing the four subtypes of BC, namely luminal A (ER + and/or PgR + , and erb-B2–), luminal B (ER + and/or PgR + , and erb-B2 + ), HER-2 (ER–, PgR– and erb-B2 + ), and basal (ER–, PgR– and erb-B2–) was adopted.

Statistical analysis

Demographic and clinical data were descriptively analyzed. The overall survival (OS), disease specific survival (DSS) and disease free survival (DFS) were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method, and 8-year survival rates from the time of diagnosis of BC were calculated. OS was defined as time to death for any cause, DSS as time to death from BC, and DFS as the time to first recurrence of BC (local, distant or a combination). For categorical data, Fisher or χ2tests with residual analysis were used. The odds ratio (OR) between groups was calculated using direct computation from 2 × 2 tables.

Disease recurrences (DR) identified as local and/or distant relapse, and CBC were considered as outcome endpoints in relation to the different prognostic factors. Of note, when DR was considered, we excluded the ductal carcinoma in situ(DCIS) cases (25 patients) from the evaluation, and, consequently, 443 patients were analyzed.

To evaluate the single prognostic value of PFs and AGS subtypes a univariate analysis was performed. Then, to identify combinations of PFs and AGS subtypes that were likely to be most predictive of a determined outcome, automated logistic regression [14] with the bootstrap technique for variable selection and bootstrap resampling to test selection stability was used [15]. This data analysis was performed by DREES (Dose Response Explorer System) [16]. DREES is an open source available package for combined modeling of multiple dosimetric variables and clinical factors using multi-term regression modeling. Briefly, the modeling process consists of a two-step process. In the first step, the model size (number of variables significantly predictive) is estimated by bootstrapping, and in the second step the parameters are estimated using forward selection on multiple bootstrap samples, the most frequent model being the optimal one. Model predictive power is quantified using Spearman' rank (Rs) correlation coefficient.

RESULTS

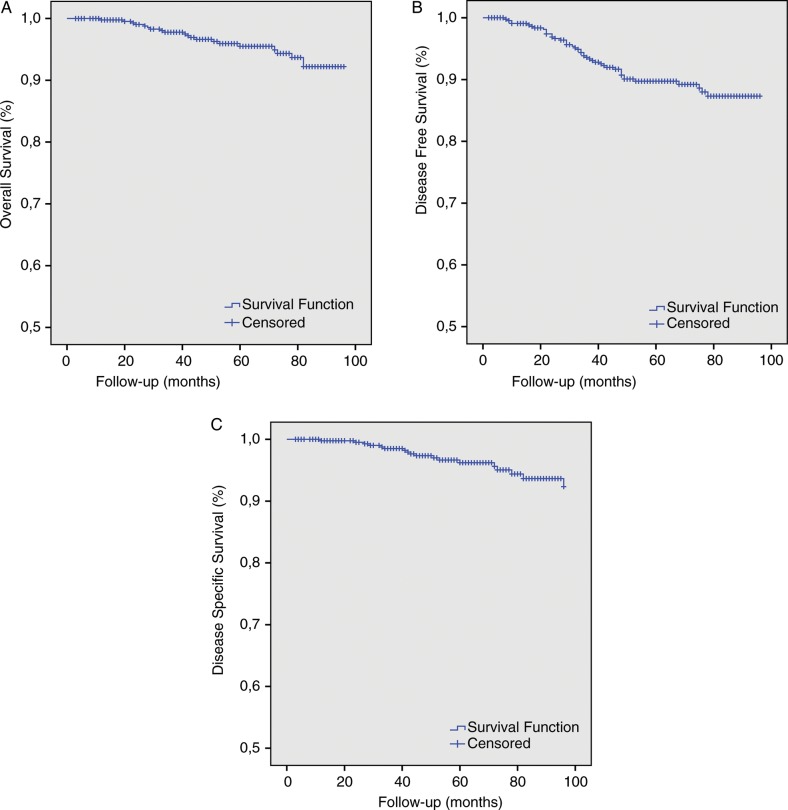

At a median follow-up of 59 months from diagnosis (range, 6–132), 90% (421/468) of patients were alive without evidence of disease. The eight-year OS and DSS was 95.1% (445/468) and 96.2% (450/468), respectively. The Kaplan-Meier estimated OS, DFS and DSS for our study are illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of (A) 8-year overall survival, (B) 8-year disease free survival, and (C) 8-year disease specific survival.

DR and CBC incidence in luminal A, luminal B, HER-2 and basal cancer subtypes are reported in Table 2. Chi square analysis showed a statistically significant difference in DR incidence (P= 0.005) and CBC incidence (P= 0.004) between the four subtypes. From residual analyses, HER-2 and basal subtypes were more likely to recur (P< 0.05) than luminal A and B patients, while basal subtypes were more likely to have CBC (P< 0.01) compared with women with non-basal tumors.

Table 2.

Disease Recurrences (DR) and Contralateral Breast Cancer (CBC) incidence in luminal A, luminal B, HER-2 and basal cancer suptypes

| DR | No DR | Totals | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Luminal A | 22 (7.3%) | 281 (92.7%) | 303 |

| Luminal B | 4 (7.0%) | 53 (93%) | 57 |

| HER-2 | 6 (28.6%)* | 15 (71.4%) | 21 |

| Basal | 12 (19.4%)* | 50 (80.6%) | 62 |

| Totals | 44 | 399 | 443 |

| CBC | No CBC | Totals | |

| Luminal A | 11 (3.5%) | 306 (96.5%) | 317 |

| Luminal B | 2 (3.2%) | 60 (96.8%) | 62 |

| HER-2 | 2 (8.0%) | 23 (92.0%) | 25 |

| Basal | 9 (14.1%)§ | 55 (85.9%) | 64 |

| Totals | 24 | 444 | 468 |

*P< 0.05 from residual analyses, §P< 0.01 from residual analyses.

From the 2 × 2 contingency table (Table 3), obtained by grouping together women with HER-2 and basal-like cancers and those with luminal A and luminal B subtypes, an OR for DR of 3.5 (95% CI1.6–5.8) was calculated. Similarly, the basal-like BC group have an OR for CBC of 4.2 (95% CI1.8–10.2), compared with luminal A, luminal B and HER-2 subtypes (Table 3).

Table 3.

Contingency table for Disease Recurrences (DR) and Contralateral Breast Cancer (CBC)

| Genetic subtypes | DR | No DR | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| HER-2 + Basal | 18 | 65 | 83 |

| Luminal A + Luminal B | 26 | 334 | 360 |

| Total | 44 | 399 | 443 |

| Genetic subtypes | CBC | No CBC | Total |

| Basal | 9 | 55 | 64 |

| Luminal A + Luminal B + HER-2 | 15 | 389 | 404 |

| Total | 24 | 444 | 468 |

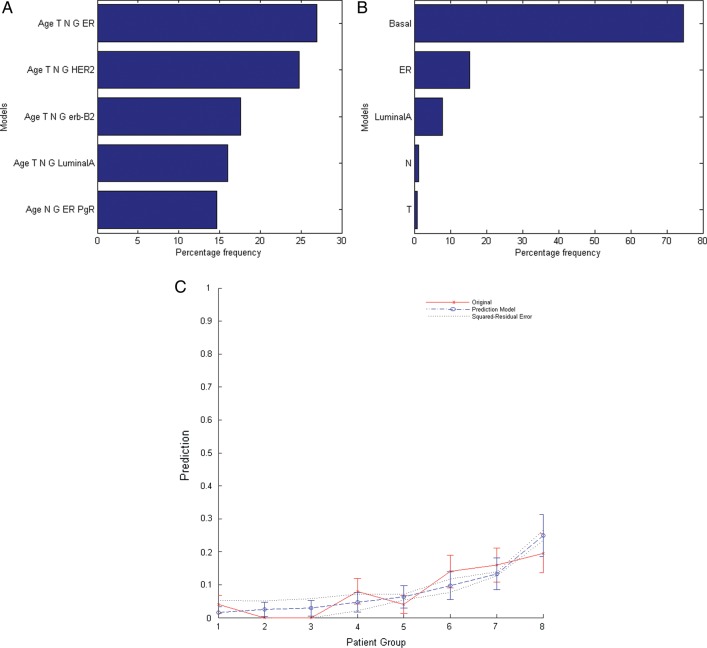

Results from univariate analysis including PFs and AGS subtypes are reported in Table 4. For DR, all variables were significant except age, erb-B2, and luminal B, while the only significant variables for CBC were ER, PgR, basal, and luminal A. For developing the DR predictive model and the CBC predictive model, all dichotomous PFs and AGS subtypes were included in the multivariate risk modeling. For DR, a five-variable model was suggested as the optimal order by bootstrap method. Logistic models were constructed using bootstrap datasets. Figure 2A shows the five most frequently models within the bootstrapped subpopulations. The optimal multivariate model includes age, T, N, G and ER (Rs = 0.23, P< 0.0001). The best-fitted model parameters and the related ORs are given in Table 4. The comparison of the mean predicted incidence of DR and the observed incidence in patients binned by predicted risk is shown in Fig. 2C. The patients were binned according to predicted risk of DR by the five-variable model (age, T, N, G, and ER) with equal patient numbers in each bin. In regard to CBC, the result of modeling was a single-variable model. The final model includes basal-type variable (Rs = 0.203, P= 0.002) as shown in Fig. 2B. The best-fitted model parameters and the related OR are given in Table 5. From these parameters a total OR of 9.1 was obtained for patients with age < 50 years, > T1, N + , G3 and ER– .

Table 4.

Disease Recurrences (DR) and Contralateral Breast Cancer (CBC) univariate analyses significance level

| Variable | DR | CBC |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.277 | 0.447 |

| N | < 0.001 | 0.44 |

| T | 0.010 | 0.122 |

| G | 0.002 | 0.075 |

| ER | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| PgR | 0.008 | 0.017 |

| Erb-B2 | 0.347 | 0.809 |

| Luminal A | 0.006 | 0.018 |

| Luminal B | 0.431 | 0.466 |

| HER-2 | 0.003 | 0.503 |

| Basal | 0.007 | < 0.001 |

Fig. 2.

The five most frequent models for Disease Recurrence (DR) (A) and for Contralateral Breast Cancer (B) according to bootstrap simulations. Mean predicted incidence of DR vs observed incidence in patients binned by predicted risk (C). The patient were binned according to predicted risk of DR by the five-variable model (Age, T, N, G and ER) with equal patient numbers in each bin (patients group).

Table 5.

Disease Recurrences (DR) and Contralateral Breast Cancer (CBC) logistic regression modeling coefficients, regression modeling constants and odds ratios (OR)

| Variable | Coefficient | OR | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DR | ||||

| Age | –0.54 | 0.6 | 0.18 | |

| T | 0.57 | 1.7 | 0.16 | |

| N | 0.95 | 2.5 | 0.018 | |

| G | 0.86 | 2.3 | 0.059 | |

| ER | 0.74 | 2.0 | 0.071 | |

| Constant | –3.65 | |||

| CBC | ||||

| Basal | 1.87 | 6.5 | 0.001 | |

| Constant | –3.67 |

DISCUSSION

In this study, we explored the feasibility of developing a prognostic model combining clinical variables and AGS subtypes for BC patients treated with postoperative radiotherapy.

The identification of BC patients with a greater risk of developing a specific event may enable tailoring of the follow-up and therapeutic strategies. The widening of diagnostic and therapeutic options in BC certainly allows, and at same time requires, a more individualized management of this patient population.

Gene expression signatures can provide a powerful tool for predicting outcome for BC patients but,for technical and economic considerations, are not widely used.

A surrogate approximation, based on hormone receptors and HER-2 status [10–12], may be a valuable classification for building outcome prediction models to be routinely used clinically. It has been shown that this classification has an impact on BC specific survival and distant metastases rates [17]. Moreover, robust risk models for BC can be created combining clinical variables and gene expression signatures [8, 9] with significant improvement compared with the clinico-pathological model or subtype model alone.

In this framework, the present study expands on the potential of multivariable risk modelling, and extends the complexity of the analysis in order to evaluate and quantify the possible advantage of combining clinical variables and a surrogate AGS based on hormone receptor and erb-B2 status.

We used modern resampling statistical methods, such as bootstrapping, to obtain model-based inferences regarding DRs and CBC. When only limited samples are available, the bootstrap method involves generating a number of resamples of an observed dataset. Each of these resamples has a size equal to the observed dataset and is obtained by random sampling with replacement from the original dataset [18]. The advantage of the applied procedure is that the use of the Rs correlation coefficient allows a very effective identification of the relatively stronger combination of the variables able to predict a definite outcome.

In our unselected population of localized BC-bearing patients, at a median follow-up of 59 months we found DFS and OS to be 90% and 95.1%, respectively. These results are in agreement with other series reported in the literature [17, 19].

The AGS subtyping showed, as expected, a worse prognosis for basal and HER-2 subtypes (the HER-2 subtype did not receive at that time any adjuvant therapy with trastuzumab) with an augmented risk of DR equal to 3.5. The multivariate risk modeling, including clinical variables along with genetic signature subtyping, indicated as the optimal model for prediction of DR a five-variable combination that included age, T, N, G, and ER status. Figure 2C graphically shows the good agreement between the predicted incidence by our five-parameter model and the actuarial incidence of DR in each patient bin. Of note, in our univariate analysis age was not a significant variable while it was recovered as a predictive factor by the bootstrap resampling technique. This suggests that the significance of age as a predictor was not found using univariate analysis because of the low number of events in our study population. In Table 5we showed the best fitted-model parameters giving a total OR of 9.1 for patients of age < 50 years, > T1, N + , G3 and ER–. This finding, that excludes the genetic signature from the best significant predictive factors for DR, is apparently in contradiction with other similar analyses reported in the literature [7–9]. It should be remarked that these other studies regarded mainly node-negative BC patients. An analysis performed on the node-negative subgroup of our patients, although not significant because of the limited number of events, resulted in agreement with these previous studies and showed that T, G and basal subtype represent the best predictive combination of prognostic factors (data not shown) in this subset of BC patients.

In regard to CBC, our study identified the basal subtype as the only predictive variable for CBC. However, it must be remarked that in the basal type subset of patients there is a higher proportion of BRCA-1 and -2 mutant patients [20], and that BRCA-1 and -2 mutant patients carry a high risk of CBC [21]. Occurrence of CBC has been shown to increase the mortality for BC [3] and an early recognition of CBC has been associated with a decrease of BC mortality [22]. As a consequence, the identification of basal type patients as a subgroup with an augmented risk (OR = 6.5) of developing CBC may represent an important finding in relation to tailoring a follow-up program for these patients.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, through multivariable outcome predictive models we found in our cohort that the combination of the clinical variables age, T, N, G and ER represents the best predictor of DR, and that the basal subtype was the only risk factor significantly associated with CBC. These results may represent a helpful contribution to the personalized management of BC patients.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ferlay J, Autier P, Boniol M, et al. Estimates of the cancer incidence and mortality in Europe in. Ann Oncol2007. 2006;18:581–92. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yi M, Meric-Bernstam F, Middleton LP, et al. Predictors of contralateral breast cancer in patients with unilateral breast cancer undergoing contralateral prophylactic mastectomy. Cancer. 2009;115:962–71. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vichapat V, Garmo H, Holmberg L, et al. Prognosis of metachronous contralateral breast cancer: importance of stage, age and interval time between the two diagnoses. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;130:609–18. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1618-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Nes JG, Putter H, van Hezewijk M, et al. Tailored follow-up for early breast cancer patients: a prognostic index that predicts locoregional recurrence. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2011;36:617–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burstein H, Harris J, Morrow M. Malignant tumors of the breast. In: Devita V, Lawrence T, Rosenberg S, editors. Cancer Principles and Practice of Oncology. 9th edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011. pp. 1401–46. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perou CM, Sorlie T, Eisen MB, et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000;406:747–52. doi: 10.1038/35021093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Desmedt C, Haibe-Kains B, Wirapati P, et al. Biological processes associated with breast cancer clinical outcome depend on the molecular subtypes. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:5158–65. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fan C, Prat A, Parker JS, et al. Building prognostic models for breast cancer patients using clinical variables and hundreds of gene expression signatures. BMC Med Genomics. 2011;4:3. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-4-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parker JS, Mullins M, Cheang MC, et al. Supervised risk predictor of breast cancer based on intrinsic subtypes. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1160–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nguyen PL, Taghian AG, Katz MS, et al. Breast cancer subtype approximated by estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and HER-2 is associated with local and distant recurrence after breast-conserving therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2373–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.4287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hattangadi-Gluth JA, Wo JY, Nguyen PL, et al. Basal subtype of invasive breast cancer is associated with a higher risk of true recurrence after conventional breast-conserving therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82:1185–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.02.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murthy V, Chamberlain RS. Recommendation to revise the AJCC/UICC breast cancer staging system for inclusion of proven prognostic factors: ER/PR receptor status and HER2 neu. Clin Breast Cancer. 2011;11:346–7. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hannemann J, Kristel P, van Tinteren H, et al. Molecular subtypes of breast cancer and amplification of topoisomerase II alpha: predictive role in dose intensive adjuvant chemotherapy. Br J Cancer. 2006;95:1334–41. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lemeshow S, Hosmer DW., Jr. Estimating odds ratios with categorically scaled covariates in multiple logistic regression analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 1984;119:147–51. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.El Naqa I, Bradley J, Blanco AI, et al. Multivariable modeling of radiotherapy outcomes, including dose-volume and clinical factors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64:1275–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.El Naqa I, Suneja G, Lindsay PE, et al. Dose response explorer: an integrated open-source tool for exploring and modelling radiotherapy dose-volume outcome relationships. Phys Med Biol. 2006;51:5719–35. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/51/22/001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanpaolo P, Barbieri V, Genovesi D. Prognostic value of breast cancer subtypes on breast cancer specific survival, distant metastases and local relapse rates in conservatively managed early stage breast cancer: A retrospective clinical study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2011;37:876–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Efron B. Jackknife, bootstrap, other resampling methods in regression-analysis -discussion. Annals of Statistics. 1986;14:1301–4. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zaky SS, Lund M, May KA, et al. The negative effect of triple-negative breast cancer on outcome after breast-conserving therapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:2858–65. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1669-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Timms KM, Liu S, et al. Incidence and outcome of BRCA mutations in unselected patients with triple receptor-negative breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:1082–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Metcalfe K, Gershman S, Lynch HT, et al. Predictors of contralateral breast cancer in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Br J Cancer. 2011;104:1384–92. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu WL, Jansen L, Post WJ, et al. Impact on survival of early detection of isolated breast recurrences after the primary treatment for breast cancer: a meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;114:403–12. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]