Abstract

Background & Aims

The prevalence of chronic constipation (CC) has been reported to be as high as 20% in the general population, but little is known about its natural history. We estimated the natural history of CC and characterized features of persistent CC and non-persistent CC, compared to individuals without constipation.

Methods

In a prospective cohort study, we analyzed data collected from multiple, validated surveys (minimum of 2) of 2853 randomly selected subjects, over a 20-year period (median, 11.6 years). Based on responses, subjects were characterized as having persistent CC, non-persistent CC, or no constipation. We assessed the association between constipation status and potential risk factors using logistic regression models, adjusting for age and sex.

Results

Of the respondents, 84 had persistent CC (3%), 605 had non-persistent CC (21%), and 2164 had no symptoms of constipation (76%). High scores from the somatic symptom checklist (odds ratio [OR] =2.1; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.3–3.4) and frequent doctor visits (OR=2.0; 95% CI, 1.0–3.8) were significantly associated with persistent CC, compared to subjects with no constipation symptoms. The only factor that differed was increased use of laxatives or fiber among subjects with persistent CC (OR=3.0; 95% CI, 1.9–4.9).

Conclusion

The prevalence of constipation might be exaggerated—the proportion of the population with persistent CC is low (3%). Patients with persistent and non-persistent CC have similar clinical characteristics, although individuals with persistent CC use more laxatives or fiber. CC therefore appears and disappears among certain patients, but we do not have enough information to identify these individuals in advance.

Keywords: SSC, epidemiology, determinants, diagnosis

INTRODUCTION

Constipation which is characterized by difficult, infrequent stool passage or feelings of incomplete rectal evacuation is thought to be very common in the community.1–3 Population based studies have estimated the prevalence of constipation in North America to vary between 2% and 27%, representing 4 to 56 million adults in the United States alone.4, 5 Although only a minority with constipation seek health care, constipation leads to 2.5 million physician visits per year in the United States.6, 7 Constipation probably has a clinically significant deleterious effect on health-related quality of life and represents an economic burden for the patient and health care provider.8–10 Tertiary care evaluation for constipation has been reported to cost an average of $2,752 per patient.8 Therefore, knowledge of the natural history of constipation is highly relevant to primary care providers, gastroenterologists, and health care policy makers.

Constipation is seen as a chronic symptom, as many patients have constipation-associated symptoms on a long-term basis.11, 12 Johanson and Kralstein11 reported that about 70% patients had constipation for more than 2 years based on a web-based survey. Talley et al.12 determined that in the general population, 89% of adults surveyed reported no change in their gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms during an intervening 12–20 month period. However, these data represented only a relatively short period of time that subjects may have constipation. Recently, Halder et al.13 showed that the overall prevalence of functional GI disorders including chronic constipation (CC) was stable over time, but the turnover in individual symptom status was high.

It is therefore unclear if CC is a stable syndrome over a longer period of time in the majority affected. The high prevalence rates of CC published may not reflect chronic persistent cases over time. Moreover, no data exist regarding the characteristics of and risk factors for persistent CC versus non-persistent CC. Thus, we aimed to estimate the natural history of CC in the community, and specifically characterize the patient population with persistent CC vs. non-persistent CC vs. no constipation.

METHODS

This study is a prospective, population-based longitudinal cohort study of subjects who were sent an initial GI symptom survey including constipation related questions between 1988 and 1994 and then subsequent surveys until 2009. Data from the individual cross sectional cohorts have been previously published in part,2, 12–20 and each survey which measured constipation experienced during the past year was included in this current study. This study was approved by the institutional review boards of the Mayo Foundation and the Olmsted Medical Center.

Subjects

The Olmsted County population comprises approximately 120,000 persons of which 90% are white; sociodemographically, the community is similar to the U.S. white population.21, 22 Eighty percent of the Olmsted County population resides within five miles of Rochester, and County residents receive their medical care almost exclusively from two group practices: Mayo Medical Center and Olmsted Medical Center. Mayo Clinic has maintained a common medical record system with its two affiliated hospitals (St. Marys and Rochester Methodist) for over 100 years. Recorded diagnoses and surgical procedures are indexed, including the diagnoses made for outpatients seen in office or clinic consultations, emergency room visits or nursing home care, as well as the diagnoses recorded for hospital inpatients, at autopsy examination or on death certificates.21, 22 The system was further developed by the Rochester Epidemiology Project, which created similar indices for the records of other providers of medical care to local residents, most notably the Olmsted Medical Group and its affiliated Olmsted Community Hospital (Olmsted Medical Center). Annually, over 80% of the entire population is attended by one or both of these two practices, and nearly everyone has an encounter at least once during any given four-year period.21, 22 Therefore, the Rochester Epidemiology Project medical records linkage system also provides what is essentially an enumeration of the population from which samples can be drawn.

As part of previous investigations,2, 12, 16–20 we utilized the enumeration of the Olmsted County population as described above to select age- (five-year intervals) and sex-stratified random samples of Olmsted County adult residents. The initial two cohorts were middle aged (20–50 and 30–65 years), then two elderly cohorts (age >65) were identified. These samples ranged in size from 800 to 2200 residents. They were mailed valid self-report symptom questionnaires from November 1988 to June 1994, i.e., the ‘baseline’ or initial survey. At the outset, the complete (inpatient and outpatient) medical records of the individuals enumerated in the sample were reviewed. Subjects were excluded if they had significant illnesses which might cause GI symptoms or impair their ability to complete the questionnaire (e.g., metastatic cancer, major stroke), had a major psychotic episode, mental retardation or dementia, or had a history of major abdominal surgery.

Further, revised versions of the study questionnaire and an explanatory letter were then mailed to the original cohort in follow-up surveys in 2003–2004 and 2008–2009. Subjects who had died, moved from Olmsted County or denied authorization to use their medical records for research, as required by Minnesota law, were excluded from these mailings. However, passive non-responders to the initial surveys were included. Reminder letters were mailed at 2, 4 and 7 weeks. Subjects who indicated at any point that they did not wish to complete the survey were not contacted further. Otherwise, non-responders were contacted by telephone at 10 weeks to request their participation and verify their residence within the country.

Among a total of 4850 subjects who were mailed at least 2 surveys over the 20 years, a total of 2853 subjects (59%) responded to a minimum of 2 surveys. A total of 60% of females responded and 57% of males, with the overall mean (±SD) age of respondents being 53 (±15) and in non-respondents, 53 (±17) years. Based on a logistic regression model for response (yes/no), females had a slightly greater odds for response relative to males (OR=1.1, 95% CI (1.0,1.3), p=0.053), but age was not associated with response, (OR=1.0 95% CI (0.96,1.04) per 10 years of age, p=0.95).

Questionnaire

The Talley Bowel Disease Questionnaire (BDQ)18–20 was designed as a self-report instrument to measure symptoms experienced over the prior year and to collect the past medical history. Previous testing has shown this instrument to be reliable, with a median kappa statistic for symptom items of 0.78 (range, 0.52–1.00); reliability was assessed by asking subjects to complete the survey on two occasions two weeks apart in the outpatient setting. It has also been demonstrated to have adequate content, predictive and construct validity.18–20 The original BDQ contained 46 GI symptom-related items including constipation related questions; 25 items that measure past illness, health care use, and sociodemographic variables; and a valid measure of non-GI somatic complaints, the Somatic Symptom Checklist (SSC).23 The SSC consists of 12 non-GI and 5 GI symptoms or illnesses. Respondents are instructed to indicate how often each symptom occurred (on a scale of 0, indicating not a problem, to 4, indicating occurs daily) and how bothersome each was (on a scale of 0, not a problem, to 4, extremely bothersome when occurs) during the past year, using separate 5-point scales. SSC score also has been shown to be a reliable and valid measure of somatic complaints.23, 24 Further, the original BDQ was modified for the elderly25 and derivatives created for specific conditions.26, 27 These versions were also tested before implementation. The BDQ has been further refined and retested with excellent results.28, 29 Modifications of the original BDQ with the non-GI SSC questions were used in the follow-up surveys to measure GI symptoms including constipation symptoms experienced over the prior year.

Definition

Chronic constipation (CC) was defined according to modified Rome II criteria by 2 or more of the following 4 symptoms in the last year: 1) <3 defecations per week, 2) straining on at least 25% of defecations, 3) hard stools on at least 25% of defecations, 4) feelings of incomplete rectal evacuation on at least 25% of defecations. In addition, subjects with CC did not meet the criteria of irritable bowel syndrome.

Classification of chronic constipation

Persistent chronic constipation

Subjects with constipation who met the constipation criteria on all surveys they returned.

Non-persistent chronic constipation

Subjects with constipation who met the constipation criteria on at least one survey but not all.

Statistical analysis

The overall univariate associations between constipation status and demographic, clinical, and symptom characteristics at baseline (e.g., age, gender, body mass index [BMI], SSC score and GI symptoms) were assessed using a non-parametric (i.e., the Kruskal-Wallis test) approach for quantitative characteristics and contingency table methods (i.e., a chi-square test or Fisher’s Exact test as warranted) for discrete characteristics. The odds ratios for specific constipation groups (Persistent vs. None, Non-persistent vs. None and Persistent vs. Non-persistent) associated with each characteristic were estimated from the coefficients in a logistic regression model (generalized logit link function), after adjusting for age and gender.

In order to allow for missing data on SSC scores for both often or bothersome for each non-GI symptom were averaged. Then the average often score and the average bothersome score were summed to create a total SSC score.

RESULTS

A total of 2853 subjects responded to a minimum of 2 surveys over the 20-year period, and the overall median follow-up was 11.6 years (range: 10 months to 20.2 years). The mean (±SD) age of responders was 53(±15) years, and 53% were female.

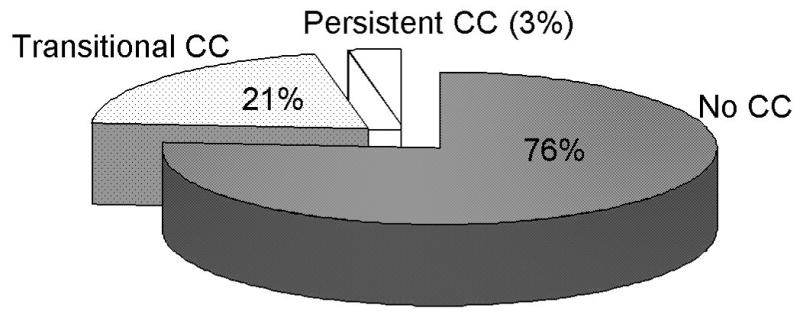

Among a total of 2853 respondents, 84 subjects (3%, 95% CI=2, 4), had persistent CC, 605 subjects (21%, 95% CI=20, 23) non-persistent CC, and 2164 subjects (76%, 95% CI=74, 77) without CC (Figure 1). The average intervals between surveys was 7.0 years in the group of subjects without CC, 6.6 years in the non-persistent CC group, and 6.2 years in the persistent CC group, but no association of group with between survey interval was detected. The survey frequency proportions in each group differed, with, for example, 75% of persistent CC responding to two surveys but 49% of nonpersistent CC and 57% of no CC subjects responding to two surveys.

Figure 1.

Proportion of those with persistent chronic constipation, non-persistent chronic constipation, or no chronic constipation

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics according to constipation status. Those with overall CC including persistent and non-persistent CC had a mean age of 54 (±15) years, and 39% were male. Significant univariate associations with constipation group were observed for age, gender, SSC score, education level, and several clinical characteristics (Table 1). Notably, higher SSC scores were observed in those with persistent or non-persistent CC compared to those with no constipation with the highest somatic symptom scores in the non-persistent CC group. In addition, a larger proportion of patients with persistent CC or non-persistent CC had visited physicians (>5 times in the last year) and reported more frequent laxative/fiber use than those without CC.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the subjects in the Olmsted County, Minnesota, by chronic constipation (CC) subgroup status

| Persistent CC n = 84 | Non-persistent CC n = 605 | No constipation symptoms n = 2164 | p-value† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD (yrs) | 55 ± 15 | 54 ± 15 | 53 ± 14 | 0.12 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female (n=1509) | 49 (58%) | 370 (61%) | 1090 (50%) | <0.01 |

| BMI, mean ± SD | 28 ± 6 | 29 ± 7 | 29 ± 7 | 0.44 |

| SSC score, mean ± SD | 0.6 ± 0.4 | 0.7 ± 0.5 | 0.5 ± 0.4 | <0.01 |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Smoking, current (n=228) | 5 (6%) | 55 (9%) | 168 (8%) | 0.78 |

| Alcohol use | ||||

| 1–6 drinks per week (n=644) | 13 (16%) | 150 (25%) | 481 (22%) | 0.10 |

| ≥ 7 drinks per week (n=199) | 7 (8%) | 39 (6%) | 153 (7%) | |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Married (n=1624) | 43 (51%) | 347 (57%) | 1234 (57%) | 0.79 |

| Education level | ||||

| Less than high school (n=143) | 3 (4%) | 39 (6%) | 101 (5%) | 0.002 |

| High school/some college (n=1605) | 53 (63%) | 372 (62%) | 1180 (55%) | |

| College graduate or higher (N=1077) | 28 (33%) | 191 (32%) | 858 (40%) | |

| Cholecystectomy (n=144) | 3 (4%) | 36 (6%) | 105 (5%) | 0.59 |

| Appendectomy (n=516) | 20 (24%) | 133 (22%) | 363 (17%) | 0.06 |

| Visiting a physician > 5 times (n=227) in the last year | 11 (13%) | 66 (11%) | 150 (7%) | 0.002 |

| Laxative/fiber use (n=391) in the last year | 44 (52%) | 168 (28%) | 179 (8%) | <0.01 |

| Dyspepsia (n=96) | 4 (5%) | 41 (7%) | 51 (2%) | <0.01 |

| Gastroesophageal reflux symptoms, (n=443) | 20 (24%) | 132 (22%) | 291 (13%) | <0.01 |

Based on Kruskal-Wallis test or contingency table analysis

Gastrointestinal symptoms

Table 2 summarizes the distributions of GI symptoms at 6 months and each item of the SSC by constipation subgroup. As would be expected, all constipation related symptoms such as infrequent bowel movements, hard stools, straining, and incomplete evacuation were more frequently reported by those with constipation (persistent and non-persistent) than in those without constipation. Interestingly, those with CC had more dyspepsia and reflux symptoms, and loose bowel movements were least frequently reported in those with persistent CC. Pain related symptoms including frequent and severe abdominal pain were most often reported in those with non-persistent CC among the three groups. In particular, among 605 with non-persistent CC, 202 (33%) met the criteria for IBS on one or more surveys. Among 2164 with no CC, 552 (26%) met the criteria for IBS on one or more surveys. However, no one with persistent CC met the criteria for IBS.

Table 2.

Distribution of GI symptoms and individual SSC items by chronic constipation (CC) subgroup status

| Persistent CC n = 84 | Non-persistent CC n = 605 | No constipation symptoms n = 2164 | p-value† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mucus (n=286) | 18 (21%) | 87 (14%) | 181 (8%) | <0.01 |

| Bloating (n=555) | 36 (43%) | 212 (35%) | 307 (14%) | <0.01 |

| Abdominal pain (n=1227) | 43 (51%) | 335 (55%) | 849 (39%) | <0.01 |

| Pain severity | ||||

| mild (n=326) | 10 (12%) | 90 (15%) | 226 (10%) | <0.01 |

| moderate (n=727) | 28 (33%) | 210 (35%) | 489 (23%) | |

| severe/very severe (n=142) | 3 (4%) | 32 (5%) | 107 (5%) | |

| Urgency (n=471) | 11 (13%) | 124 (21%) | 336 (16%) | 0.01 |

| Pain frequency | ||||

| <1/week (n=920) | 31 (37%) | 234 (39%) | 655 (30%) | <0.01 |

| ≥1/week (n=304) | 12 (14%) | 100 (17%) | 192 (9%) | |

| Any blood in stool (n=158) | 9 (11%) | 64 (11%) | 85 (4%) | <0.01 |

| More than 3 BMs per day (n=139) | 5 (6%) | 34 (6%) | 100 (5%) | 0.46 |

| Loose BM (n=486) | 5 (6%) | 103 (17%) | 378 (18%) | 0.02 |

| More BM w/pain (n=411) | 5 (6%) | 91 (15%) | 315 (15%) | 0.08 |

| Somatic Symptom Checklist | ||||

| Headaches, mean ± SD | 1.0 ± 1.0 | 1.0 ± 1.1 | 0.7 ± 0.9 | <0.01 |

| Backaches, mean ± SD | 0.9 ± 1.1 | 1.3 ± 1.3 | 1.0 ± 1.1 | <0.01 |

| Asthma (wheezing), mean ± SD | 0.1 ± 0.3 | 0.1 ± 0.5 | 0.1 ± 0.5 | 0.82 |

| Insomnia, mean ± SD | 1.0 ± 1.1 | 0.9 ± 1.1 | 0.6 ± 0.9 | <0.01 |

| Fatigue (tiredness), mean ± SD | 1.3 ± 1.1 | 1.3 ± 1.2 | 0.8 ± 1.0 | <0.01 |

| General stiffness, mean ± SD | 1.1 ± 1.1 | 1.2 ± 1.4 | 0.9 ± 1.1 | <0.01 |

| Heart palpitations, mean ± SD | 0.3 ± 0.6 | 0.3 ± 0.7 | 0.2 ± 0.5 | <0.01 |

| Eye pain associated with reading, mean ± SD | 0.2 ± 0.5 | 0.3 ± 0.8 | 0.2 ± 0.5 | <0.01 |

| Dizziness, mean ± SD | 0.3 ± 0.8 | 0.3 ± 0.8 | 0.2 ± 0.5 | <0.01 |

| Weakness, mean ± SD | 0.3 ± 0.7 | 0.3 ± 0.8 | 0.1 ± 0.5 | <0.01 |

| High blood pressure, mean ± SD | 1.2 ± 0.6 | 0.4 ± 0.9 | 0.3 ± 0.7 | 0.07 |

Based on Kruskal-Wallis test or contingency table analysis

BM = bowel movement

Association between clinical features and constipation status

The odds ratios for specific constipation subgroups associated with demographic and clinical characteristics are given in Table 3. Greater SSC scores, frequent physician visits, and laxative/fiber use were associated with greater odds for persistent CC compared to those without CC. Similarly, greater SSC scores, frequent doctor visits, and laxative/fiber use were significant predictors of those with non-persistent CC vs. those without CC. However, most characteristics were not significant discriminators of persistent CC vs. non-persistent CC, except increased laxative/fiber use was associated with increased odds for persistent CC (vs. non-persistent, Table 3).

Table 3.

Associations between clinical characteristics and chronic constipation (CC) subgroups [OR, (95% CI)]

| Persistent CC vs. no CC | Non-persistent CC vs. no CC | Persistent CC vs. non-persistent CC | p-value† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age per 10 years | 1.1 (1.0,1.3) | 1.1 (1.0,1.1) | 1.0 (0.9,1.2) | 0.09 |

| Female gender | 1.4 (0.9,2.2) | 1.6 (1.3,1.9) | 0.9 (0.6,1.4) | <0.01 |

| BMI+ | 1.0 (0.9,1.0) | 1.0 (1.0,1.0) | 1.0 (0.9,1.0) | 0.50 |

| SSC score+ | 2.1 (1.3,3.4) | 2.9 (2.2,3.4) | 0.8 (0.5,1.3) | <0.01 |

| Smoking, current+ | 0.7 (0.3,1.8) | 1.0 (0.7,1.4) | 0.7 (0.3,1.8) | 0.75 |

| Alcohol+ | ||||

| None | 2.0 (1.0,4.1) | 1.2 (0.9,1.5) | 1.7 (0.8,3.6) | 0.09 |

| ≥ 7 drinks/week | 1.8 (0.7,4.7) | 0.9 (0.6,1.3) | 2.0 (0.7,5.5) | 0.39 |

| Married+ | 1.3 (0.6,2.8) | 1.0 (0.7,1.3) | 1.3 (0.6,2.9) | 0.86 |

| Education level+ | ||||

| Less than high school | 0.6 (0.2,2.1) | 1.3 (0.9,1.9) | 0.5 (0.2,1.7) | 0.35 |

| College graduate or higher | 0.8 (0.5,1.2) | 0.7 (0.6,0.9) | 1.0 (0.6,1.7) | 0.008 |

| Cholecystectomy+ | 0.7 (0.3,2.1) | 1.2 (0.8,1.7) | 0.6 (0.2,1.9) | 0.59 |

| Appendectomy+ | 1.2 (0.7,2.1) | 1.3 (1.0,1.6) | 0.9 (0.5,1.6) | 0.11 |

| Visiting a physician > 5 times+ | 2.0 (1.0,3.8) | 1.6 (1.2,2.1) | 1.2 (0.6,2.5) | 0.004 |

| Laxative/fiber use+ | 12.1 (7.5,19.4) | 4.0 (3.2,5.1) | 3.0 (1.9,4.9) | <0.01 |

| Dyspepsia | 2.0 (0.7,5.8) | 2.9 (1.9,4.5) | 1.1 (0.6,1.9) | <0.01 |

| Gastroesophageal reflux symptoms | 2.0 (1.2,3.3) | 1.8 (1.4,2.3) | 0.7 (0.2,2.0) | <0.01 |

From logistic regression models, overall test for the three constipation subgroups

Models adjusted for age and gender

The association between constipation status and lower GI symptoms is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Associations between individual gastrointestinal symptoms and chronic constipation (CC) status [OR, (95% CI)]

| Persistent CC vs. no CC | Non-persistent CC vs. no CC | Persistent CC vs. Non-persistent CC | p-value† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mucus+ | 3.1 (1.8,5.4) | 1.8 (1.4,2.4) | 1.7 (1.0,3.1) | <0.01 |

| Bloating+ | 4.4 (2.8,6.9) | 3.1 (2.5,3.8) | 1.4 (0.9,2.2) | <0.01 |

| Abdominal pain+ | 1.7 (1.1,2.7) | 2.0 (1.6,2.4) | 0.9 (0.5,1.4) | <0.01 |

| Pain severity+ | ||||

| mild | 1.5 (0.7,3.1) | 2.0 (1.5,2.7) | 0.7 (0.4,1.5) | <0.01 |

| Moderate | 1.9 (1.2,3.2) | 2.1 (1.7,2.6) | 0.9 (0.5,1.5) | <0.01 |

| severe/very severe | 1.0 (0.3,3.1) | 1.5 (1.0,2.3) | 0.6 (0.2,2.2) | 0.17 |

| Urgency+ | 0.8 (0.4,1.5) | 1.3 (1.1,1.7) | 0.6 (0.3,1.1) | 0.04 |

| Pain frequency+ | ||||

| < 1/week | 1.6 (1.0,2.6) | 1.8 (1.5,2.2) | 0.9 (0.5,1.5) | <0.01 |

| ≥ 1/week | 2.1 (1.1,4.0) | 2.6 (1.9,3.4) | 0.8 (0.4,1.6) | <0.01 |

| Any blood in stool+ | 3.2 (1.4,7.1) | 2.8 (1.9,4.0) | 1.1 (0.5,2.6) | <0.01 |

| More than 3 BMs/day+ | 1.2 (0.5,3.0) | 1.2 (0.8,1.8) | 1.0 (0.4,2.6) | 0.60 |

| Loose BM+ | 0.3 (0.1,0.8) | 1.0 (0.8,1.2) | 0.3 (0.1,0.8) | 0.04 |

| More BM w/pain+ | 0.4 (0.2,0.9) | 1.0 (0.8,1.3) | 0.4 (0.1,0.9) | <0.01 |

From logistic regression models, overall test for the three constipation subgroups.

models adjusted for age and gender

BM = bowel movement

Most of the lower GI symptoms, including any blood in stool, were associated with greater odds for those with persistent CC or non-persistent CC compared to those without CC except diarrhea related symptoms (Table 4). Interestingly, most of the GI symptoms were not significant discriminators of persistent CC vs. non-persistent CC, though loose bowel movements and more bowel movements with pain had significantly decreased odds for persistent CC compared to non-persistent CC.

DISCUSSION

This is to our knowledge the first population-based longitudinal study to present U.S. data on the chronicity of constipation over a 20 year timeframe. We observed the prevalence of persistent CC over a 20-year period was only 3%. In contrast, the prevalence of non-persistent CC over a 20-year period was 21%. Those with persistent or non-persistent CC were more likely to report higher SSC scores and frequent physician visits relative to those without constipation. However, those with persistent CC were similar to those with non-persistent CC, except for fiber/laxative use, in terms of demographic features and other GI symptoms.

The prevalence of constipation has been reported to be as high as 27% of the population depending on demographic factors, sampling, and definition, but only a minority visits the clinic.5, 6, 30–32 In our study, we also observed the prevalence of overall CC including persistent and nonpersistent CC over a 20-year period was about 24%, which is similar to other prevalence data. However, we observed only 3% of the population had persistent CC over a 20-year period, which might be a truer indication of the chronicity of constipation. By the recent Rome criteria,33 functional constipation is defined by having constipation related symptoms with symptom onset at least 6 months prior to diagnosis. Traditionally, the symptom of CC has been considered to persist over a very prolonged period of time, perhaps lifelong. Talley et al.12 reported that 89% of adults surveyed reported no change in their GI symptoms during an intervening 12–20 months in the general population.12 Johanson and Kralstein11 also showed that about 70% patients had constipation for more than 2 years by the web-based survey. Moreover, a random sample survey in Sweden in 1988, 1989, and then 1995 showed that among those with IBS at baseline, 55% continued to report IBS at both follow-up surveys.34 In another study, Halder et al.13 evaluated the natural history of functional GI disorders using multiple surveys over a 12-year period in a community and observed that 40% of people with a GI symptom at baseline had different symptoms at follow-up. Moreover, among people with constipation at the initial survey, only about 22% still had constipation on the follow-up survey. This study showed only 3% of people had persistent CC in a community over a longer 20-year period. Thus, it can be concluded that CC is less frequent in a community over a longer period of time, and the estimated prevalence of CC in previous cross-sectional studies is likely to have been exaggerated. Others have highlighted that only a minority of those with constipation who have chronic or severe symptoms seek health care.6, 33

Like many other studies have shown,32, 35–37 we observed that older age and a high SSC score were associated with CC regardless of chronicity (persistent or non-persistent), relative to subjects without constipation. The association of CC with advancing age might reflect the increased prevalence of secondary causes of constipation (e.g., an increased prevalence of Parkinson’s disease, diabetes mellitus, constipating medication use, or the increasing prevalence of other disabling conditions).37 In addition, there is a considerable body of evidence supporting an association between psychological distress, environmental stress, and functional GI disorders, including constipation.32, 38, 39 Rao et al.39 showed that patients with constipation had significant evidence of increased psychological distress compared to control subjects, irrespective of the underlying pathophysiology such as slow colonic transit or dyssynergic defecation. Thus, both older age and high somatization trait may be causally linked with constipation.

An interesting hypothesis explored in the current study is whether those with persistent CC are different from those with non-persistent CC or whether these two forms of CC exist as a temporal spectrum of the same condition. We evaluated for differences between persistent CC and non-persistent CC, and observed that there were no distinct differences in terms of demographic features between these two groups aside from laxative/fiber use. Certain constipation related symptoms such as infrequent, hard stools, straining, or feelings of incomplete evacuation, were more commonly reported in those with persistent CC, while pain and diarrhea-related symptoms such as loose bowel movements and increased bowel movements with abdominal pain were more commonly reported by those with non-persistent CC. Thus, it could be inferred that those with persistent constipation are a more homogenous group, with more constipation symptoms and less diarrhea symptoms. Interestingly, the characteristics of those with non-persistent CC might reflect some portion of underlying unrecognized IBS. Further study of outcomes according to chronicity of constipation status may provide a better understanding of these two groups and such work is now needed.

The strengths of the current study include the investigation of a random community sample that was not seeking health care for their bowel complaints, which should have minimized selection bias. The fact that we employed a previously validated self-report symptom questionnaire also increases confidence in the results.18 This study also had limitations. In particular, this study did not assess the whole study period of CC, because subjects could have developed and then lost symptoms between surveys; the current study is limited to the survey responses. However, this study is in fact novel; no previous work has quantified constipation over a 20-year period of time in the general population. These data cannot be generalized outside the white U.S. population because the racial composition of this community is predominantly Caucasian.21 The prevalence of constipation may vary across different countries and cultures, but at a minimum, our data are probably generalizable to the U.S. Caucasian population.

We conclude from this population-based study that the proportion with persistent CC in the community is 3%. Persistent CC has similar clinical characteristics to non-persistent CC.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Lori R. Anderson for her assistance in the preparation of the manuscript.

Grant Support: This study was sponsored by Takeda Pharmaceuticals and was made possible by the Rochester Epidemiology Project (Grant R01- AG034676 from the National Institute on Aging).

Abbreviations

- BDQ

Bowel Disease Questionnaire

- BM

bowel movement

- BMI

body mass index

- CC

chronic constipation

- GI

gastrointestinal

- SSC

the Somatic Symptom Checklist

Footnotes

Disclosures: Dr. Talley and Mayo Clinic have licensed the Talley Bowel Disease Questionnaire.

Specific author contributions: Design, analysis, writing and revising of this paper: Rok Seon Choung, Enrique Rey G. Richard Locke III, Charles Baum, Alan R. Zinsmeister, and Nicholas J. Talley. Statistical analysis: Alan R. Zinsmeister and Cathy D. Schleck.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Pare P, Ferrazzi S, Thompson WG, et al. An epidemiological survey of constipation in canada: definitions, rates, demographics, and predictors of health care seeking. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:3130–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.05259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Talley NJ, Weaver AL, Zinsmeister AR, et al. Functional constipation and outlet delay: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:781–90. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90896-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sandler RS, Jordan MC, Shelton BJ. Demographic and dietary determinants of constipation in the US population. Am J Public Health. 1990;80:185–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.2.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drossman DA, Li Z, Andruzzi E, et al. U.S. householder survey of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Prevalence, sociodemography, and health impact. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1569–80. doi: 10.1007/BF01303162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stewart WF, Liberman JN, Sandler RS, et al. Epidemiology of constipation (EPOC) study in the United States: relation of clinical subtypes to sociodemographic features. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:3530–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sonnenberg A, Koch TR. Physician visits in the United States for constipation: 1958 to 1986. Dig Dis Sci. 1989;34:606–11. doi: 10.1007/BF01536339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Higgins PD, Johanson JF. Epidemiology of constipation in North America: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:750–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rantis PC, Jr, Vernava AM, 3rd, Daniel GL, et al. Chronic constipation--is the work-up worth the cost? Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:280–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02050416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Irvine EJ, Ferrazzi S, Pare P, et al. Health-related quality of life in functional GI disorders: focus on constipation and resource utilization. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1986–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dennison C, Prasad M, Lloyd A, et al. The health-related quality of life and economic burden of constipation. Pharmacoeconomics. 2005;23:461–76. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200523050-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johanson JF, Kralstein J. Chronic constipation: a survey of the patient perspective. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:599–608. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Talley NJ, Weaver AL, Zinsmeister AR, et al. Onset and disappearance of gastrointestinal symptoms and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;136:165–77. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halder SL, Locke GR, 3rd, Schleck CD, et al. Natural history of functional gastrointestinal disorders: a 12-year longitudinal population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:799–807. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choung RS, Locke GR, 3rd, Schleck CD, et al. Cumulative incidence of chronic constipation: a population-based study 1988–2003. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:1521–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choung RS, Locke GR, 3rd, Zinsmeister AR, et al. Epidemiology of slow and fast colonic transit using a scale of stool form in a community. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:1043–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Talley NJ, Fleming KC, Evans JM, et al. Constipation in an elderly community: a study of prevalence and potential risk factors. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:19–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Talley NJ, O’Keefe EA, Zinsmeister AR, et al. Prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms in the elderly: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:895–901. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)90175-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Talley NJ, Phillips SF, Melton J, 3rd, et al. A patient questionnaire to identify bowel disease. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111:671–4. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-111-8-671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Talley NJ, Phillips SF, Wiltgen CM, et al. Assessment of functional gastrointestinal disease: the bowel disease questionnaire. Mayo Clin Proc. 1990;65:1456–79. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)62169-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Talley NJ, Zinsmeister AR, Van Dyke C, et al. Epidemiology of colonic symptoms and the irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1991;101:927–34. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90717-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Melton LJ., 3rd History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996;71:266–74. doi: 10.4065/71.3.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Melton LJ., 3rd The threat to medical-records research. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1466–70. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199711133372012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Attanasio V, Andrasik F, Blanchard EB, et al. Psychometric properties of the SUNYA revision of the Psychosomatic Symptom Checklist. J Behav Med. 1984;7:247–57. doi: 10.1007/BF00845390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choung RS, Locke GR, 3rd, Zinsmeister AR, et al. Psychosocial distress and somatic symptoms in community subjects with irritable bowel syndrome: a psychological component is the rule. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1772–9. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Keefe EA, Talley NJ, Tangalos EG, et al. A bowel symptom questionnaire for the elderly. J Gerontol. 1992;47:M116–21. doi: 10.1093/geronj/47.4.m116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Locke GR, Talley NJ, Weaver AL, et al. A new questionnaire for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 1994;69:539–47. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)62245-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reilly WT, Talley NJ, Pemberton JH, et al. Validation of a questionnaire to assess fecal incontinence and associated risk factors: Fecal Incontinence Questionnaire. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:146–53. doi: 10.1007/BF02236971. discussion 153–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rey E, Locke GR, 3rd, Jung HK, et al. Measurement of abdominal symptoms by validated questionnaire: a 3-month recall timeframe as recommended by Rome III is not superior to a 1-year recall timeframe. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 31:1237–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Locke GR, 3rd, Pemberton JH, Phillips SF. American Gastroenterological Association Medical Position Statement: guidelines on constipation. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1761–6. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.20390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cook IJ, Talley NJ, Benninga MA, et al. Chronic constipation: overview and challenges. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21 (Suppl 2):1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sonnenberg A, Koch TR. Epidemiology of constipation in the United States. Dis Colon Rectum. 1989;32:1–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02554713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suares NC, Ford AC. Prevalence of, and risk factors for, chronic idiopathic constipation in the community: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1582–91. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.164. quiz 1581, 1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, et al. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1480–91. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Agreus L, Svardsudd K, Talley NJ, et al. Natural history of gastroesophageal reflux disease and functional abdominal disorders: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2905–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harari D, Gurwitz JH, Avorn J, et al. Bowel habit in relation to age and gender. Findings from the National Health Interview Survey and clinical implications. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:315–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Everhart JE, Go VL, Johannes RS, et al. A longitudinal survey of self-reported bowel habits in the United States. Dig Dis Sci. 1989;34:1153–62. doi: 10.1007/BF01537261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brandt LJ, Prather CM, Quigley EM, et al. Systematic review on the management of chronic constipation in North America. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100 (Suppl 1):S5–S21. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.50613_2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koloski NA, Boyce PM, Talley NJ. Somatization an independent psychosocial risk factor for irritable bowel syndrome but not dyspepsia: a population-based study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18:1101–9. doi: 10.1097/01.meg.0000231755.42963.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rao SS, Seaton K, Miller MJ, et al. Psychological profiles and quality of life differ between patients with dyssynergia and those with slow transit constipation. J Psychosom Res. 2007;63:441–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]